8

Technology, Alignment and Strategic Transformation

What is a business strategy? This question could provide sufficient material for an entire MBA course. For the purposes of this chapter, we will summarize our answer in a few sentences. A business strategy is a vision, a strategic intent [CAM 91]. This includes the long-term objectives, the policies and the resource allocations necessary to achieve the strategic intent [HAM 90]. The much more operational question that follows the strategic vision question is often: How do I compete with my competitors and exceed them in my markets? How can the top management implement the strategic transformation necessary to attain the strategic objectives and achieve the strategic intent?

First, we will describe the alignment between business strategy and information system strategy. Next, we will focus on the contribution of the information system and new technologies to the strategy, and the information system’s transformative contribution both to operational excellence and to new business opportunities. Lastly, we will list the characteristics of a strategic transformation linked to the information system and new technologies.

8.1. The alignment of stakeholders, territories and projects

At the beginning of this book, we saw that an organizational information system is mapped like a group of stakeholders (firms and their agents, upstream, downstream and lateral partners, and end customers), territories (the extended business) and projects (cooperation agreements, partnerships, e-business and e-commerce). Organizational management focuses on these three aspects. It is about the system to be instrumentalized by the CIO. One could say that this is what is “given” to the CIO, the strategy implemented in the Mintzberg sense at a time t, the system to be aligned [MIN 94].

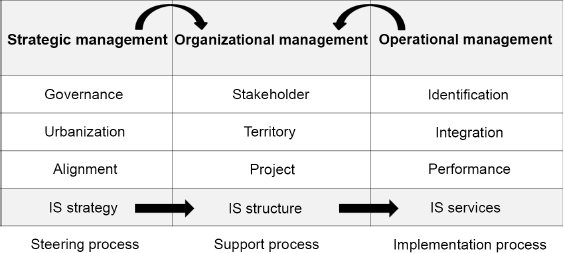

Table 8.1. Alignment of the systems and processes of organizational management [ALB 12]

As shown in Table 8.1, organizational information system management is framed by two processes: a steering process for strategic management and an implementation process for operational management. The structure is a result of the strategy and enables delivery of information system services, at the right time and to the right person, to a customer for whom it leads to value creation.

Operational management of the information system involves identification of the stakeholders (including the “CIO” stakeholder), territorial integration and project performance. As for the information system strategic management process, this focuses on stakeholder governance, territorial urbanization and project alignment. Apart from Table 8.1’s vertical analysis as summarized above, studying this table gives a grasp of the role of the decision-making system, information system and operation system within information system management. In short, in this context, “decision-making” involves governing and identifying the information system stakeholders in order to co-define their informational needs. “Informing” involves urbanizing and integrating information system territories so as to meet the co-defined needs. “Operating” relates to aligning and performing information system projects to create value.

8.2. Strategic alignment

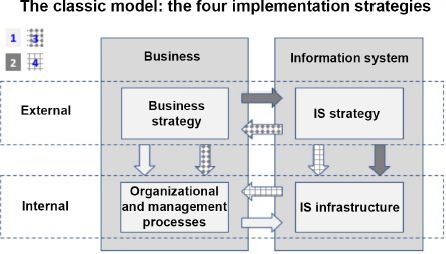

The theme of strategic adjustment is a relatively new concept in management sciences. The theoretical referential that quickly became dominant is that of the Strategic Alignment Model (SAM) [HEN 93]. This model establishes correlations between business strategy, ICT strategy, organizational and management processes and ICT infrastructure. Alignment is reckoned to happen on two levels: the external level, creating the strategic “fit”, involves making the organization’s strategic activities consistent with its choices of technology deployment, and the internal level harmonizes the organizational processes with the ICT infrastructure. The SAM-type strategic alignment model is based on its co-construction with the organizational and operational model.

Figure 8.1. Co-construction between the organizational and operational models

In doing this, the SAM model suggests a certain number of deployment pathways for strategic alignment in an organization. The general strategy can thus lead to a change in the internal organizational structures, which brings with it a reorganization of the information system infrastructure. It is also conceivable that a new information system strategy would validate the implementation of a new IS infrastructure which will have an impact on the organization’s structural models. These top-down visions of strategic alignment have been supplemented by bottom-up approaches. In all cases, the four-area model has positioned itself as a tool for the understanding and deployment of a strategic alignment process.

Depending on the case, business strategy is conceived as the driver of information system strategy (case 1) or of information systems operations (case 2), in the fairly classic hierarchical top-down perspective. In other cases, it is the information system which enables the redefinition of managerial operations (case 4), or indeed a corporate strategy (case 3). With new trends in technology, such as the use of chatbots and artificial intelligence, the information system is increasingly emerging as a driver of business strategy and operations.

8.3. Competition, technological revolutions and new strategies

The business objective is to create value and to generate a competitive advantage via this value on the market. Porter [POR 85] describes three different strategy typologies that can be implemented in relation to competitors in a given market:

- – operational excellence which suggests being a price leader;

- – differentiation which implies being a product leader;

- – a focus that enables maximum proximity to a market segment or a certain type of customer in order to be able to offer the best value.

For Porter, ICT lies at the heart of each of these three strategies. In fact, the information system can bring the operational efficiency necessary for a price-oriented strategy. Think, for instance, of the use of RFID chips to facilitate the daily deliveries of thousands of containers, or the use of drones to deliver packages, as proposed by Amazon.

The information system can also provide the keys to a better strategic focus. Through business intelligence tools and an analysis of Big Data, a travel company may, for example, aggregate airline flight information, data provided by tourist offices on tourists’ country of origin, places visited and destination and mobile geolocalization data. Using that, it can put out targeted packages with high added value for these tourists in the form of special offers on local excursions or recommendations for tours and shopping.

Finally, the information system can also be at the heart of differentiation, by bringing a unique value to the business strategy and turning this into a strategic advantage. This is the case, for example, for Netflix, which, thanks to a powerful artificial intelligence (AI) engine and a gigantic database of usage data, manages to provide its users with extremely well-tailored and accurate recommendations on future series they may enjoy.

D’Aveni suggests an alternative vision of competitive advantage, more in line with current turbulent, dynamic, open organizational contexts, the explosion of new business models and technologies [DAV 10]. D’Aveni does not believe it is possible to maintain a competitive advantage in the context of new markets or dynamic industries.

Technology is not necessarily standardized. Therefore, there are not necessarily any rules and the company can use these technologies to achieve a temporary strategic advantage. Think for instance of the use of the “Internet of Things” (IoT), which is waging a standardization war and which has not yet been regulated.

Figure 8.4. Survey of directors [PRI 16]: CEOs feel that technology is the factor that will have the greatest impact on their business in the future

In this context, investment in the IoT is still very risky, because there is no clear visibility as to which technology will become standard between Long Range (LoRa) Sigfox or Long Term Evolution for Machines (LTE-M). An equally uncertain situation exists in terms of robots, physical for industry and virtual for services (such as chatbots). Regulators and opinionists are showing an interest in robots. In an interview published on February 16, 2017, even Microsoft’s founder, Bill Gates, felt that “a robot that destroys a job should be taxed”, in order to finance social policies [COM 17]. Companies that use robots are using this technology pending the lawmakers’ decision. Similarly, some shops in France have started to accept bitcoin in spite of legislative uncertainty.

D’Aveni’s proposal is pertinent. Indeed, these new technologies and market disruptions (fed by information systems) allow only temporary competitive advantages to be built.

8.4. Strategic transformation linked to information systems and new technologies

A new strategic intent can lead the company to opt for a radically different organization, or to completely transform its information system. For example, the use of connected drones to effect deliveries will impact stakeholders, territories and business projects. Similarly, the use of a large integrated software package within a multinational (including orders, deliveries and invoicing) with robots (tasked with taking simple orders and replacing the myriad local systems) will have major consequences for the whole of the business. These are not minor projects. Strategic transformations are involved. These transformations alter the heart of an organization, its deep structure and its critical processes, often in a radical and abrupt manner. The transformation process is risky and uncertain.

There are several aspects to strategic transformation. Planning theories highlight the role of the Top Management Team (TMT) in steering the transformation along the predetermined steps and managing the change. Conversely, for emergence theorists, the strategy depends not on planning and maintaining objectives, but rather on developing priorities as they emerge over time. Change is seen as uncertain and unpredictable. The environment is chaotic and dynamic, making any planning difficult and requiring improvisation of new strategies, which, in this sense, “emerge”. Within this notion of improvisation, transformation is seen as a widespread, spontaneous, unpredictable and constantly shifting phenomenon. Orlikowski and Hoffman [ORL 97] compare organizational improvisation to improvisation by a jazz band: the musicians agree on a theme, but do not know exactly what they are going to play, unlike a symphony orchestra. During their performance, the musicians will improvise iteratively and opportunistically on each individual’s explorations, and jointly develop a creative composition. In the organizational context, the stakeholders will engage in DIY and over the course of the iterations will enable the emergence of new practices as an efficient and creative response to a local issue, new local practices that will contribute to organizational development and lead to the emergence of a new organizational structure [ORL 96]. Ciborra [CIB 92] uses the term “DIY” to describe the creative behavior of users who adjust their IT practices incrementally to changing needs via improvisation. Improvisation leads to developing new and better practices, to promoting the emergence and facilitation of knowledge creation within the organization, flexibility and organizational effectiveness [CIB 96]. In this vision, strategy is no longer the product of a TMT’s carefully designed plan, but rather the result of an emerging and collective practice, collective DIY.

New challenges arise: the reconciliation of planning and emergence in the context of a strategic transformation process linked to the information system and new technologies, but equally, the effective management of this transformation, so that the disruption is short-lived.

Besson and Rowe [BES 11] see the transformation process in four phases:

- 1) the uprooting phase, which corresponds to the Upheaval of Tushman and Romanelli’s punctuated equilibrium model [TUS 85], or to the Unfreeze of Lewin’s organizational model [LEW 51]. In this phase, the organization departs from its old model;

- 2) the exploration/construction phase, which corresponds to the Move phase of Lewin’s model; it is in this phase that the new organization is built;

- 3) the stabilization/institutionalization phase of the new organization, which partly corresponds to the convergence of Tushman’ and Romanelli’s models, and to the Freeze phase of Lewin’s model;

- 4) the optimization/routinization phase of the new organization, which corresponds to the convergence of the punctuated equilibrium model, but has no equivalent in Lewin’s model.

Each phase is also linked to various transformation strategies, and stakeholders must choose the most appropriate strategic action.

An important element to take into account is the deep structure of the business. Gersick [GER 91, p. 15] defines the deep structure as “a set of fundamental choices an organizations system has made involving basic structural elements for reconfiguring organizational units and the basic activity patterns that maintain its existence”. This deep structure is the submerged part of the iceberg that is the organization: a stable and implicit structure, difficult to grasp or understand, shaping management practices, monitoring mechanisms and strategic thinking, connecting beliefs, structures, values and systems. An attempt to transform the deep structure will cause both a certain drop in performance and a domino effect of dangerous positive and negative externalities, potentially causing the failure of the transformation. These characteristics of the deep structure explain why organizational transformations are difficult to plan and manage. Thus, the way in which the business units are connected will condition the domino effects related to the transformation. The strategic transformation will be slowed down according to the number of domino effects [HAN 07]. The more central the unit is to a node, the more we must anticipate major domino effects on units hierarchically linked to it.

Thus, we can expect domino effects in the context of a “flat hierarchy”-type interconnection to stop more quickly than those initiated in a “vertical hierarchy” type because of the units’ parallel responses to the architectural changes. The longer an architectural change lasts, the more damaging it will be. The units will have to manage current practice, business as usual and the transformation at the same time. Means and resources will be consumed in changing roles and responsibilities, reallocating resources, etc. In fact, not only is strategic transformation linked to information expensive, but the performance of the organization will also suffer in the short term.

Very recently, a new integrative conceptual framework has emerged in biology. The Biodiversity Ecosystem Function Paradigm [NAE 02] highlights the importance of biodiversity in the functioning of ecosystems. This theory combines community ecology, ecosystem ecology and evolutionary ecology into a single holistic vision. Parisot and Isckia [PAR 13] believe that this theoretical progress in biology gives “the biotope an active role in the governance of environmental conditions” (p. 14) and that it could provide solid support for the ecosystem concept in management.

In this context, we can note a number of features of the ecosystem that are favorable to information system transformation: the heterogeneity of stakeholders (trade unions, business units, pressure groups, institutions, etc.), the stakeholders’ interdependence and interactions within the ecosystem, co-evolution, coopetition and biological coupling, bringing positive and negative externalities. This aspect is of interest. Interdependent stakeholders in the transformation will come into conflict, generating coopetition, at the interface points between the old and the new organization. Changes of governance and strategic plan will result in positive and negative externalities, i.e. the domino effects mentioned above.

Managing this type of transformation calls for ambidexterity: “the ability to simultaneously pursue both incremental innovations and radical, discontinuous innovations […] by setting up divergent and contradictory structures, processes and cultures within the same firm” [TUS 96, p. 24]. This ambidexterity provides for simultaneous exploitation and exploration. Exploitation is the use of existing capabilities, while exploration could be seen as “processes set up to improve existing capabilities” [ORE 13, p. 7]. Ambidexterity allows the company to adjust to disruptive technological change: it is a way to understand how the management team manages threats to the company’s survival. Ambidexterity can, for instance, explain how the hardware manufacturer IBM became a software distributor and then a services company. According to circumstances, ambidexterity can be sequential, structural or contextual. Ambidexterity is sequential when structural development takes place over time. Ambidexterity becomes structural if two independent structures develop in parallel and simultaneously. Finally, it is contextual when ambidexterity is integrated into the organizational culture, creating people who themselves meet the conflicting demands between exploitation and exploration. In the general context of a transformation linked to the information system, we would first find the sequential approach as part of a design phase during which the organization swings between exploration and exploitation. Subsequently, the structural approach could occur as part of a pilot. We would thus have “two separate units for exploration and exploitation, aligned, but fostering different systems, controls, processes, incentives, skills and cultures” [ORE 11, p. 192]. However, these two units would be bound by a common strategic plan.

As part of the information system transformation process, these two activities of exploitation and exploration can be present in differing proportions according to the process phase – we can see the construction phase as involving a higher level of exploration activity, whereas the routinization/optimization phase would involve a greater proportion of exploitation. According to Hannan et al. [HAN 07], the informal culture of the organization is a key component of its deep structure, because it restricts future architectural choices and conditions the domino effects. Likewise, for ambidexterity theorists [ORE 13], the culture conditions the success of organizational ambidexterity – it enables the organization to tolerate the tensions of two paradoxical visions.

8.5. Towards a dynamic perspective of strategic transformation linked to the information system

We firmly take the standpoint of viewing the organization as an ecosystem: the stakeholders are heterogeneous but interdependent and are as apt to adopt competition strategies as cooperation strategies. Positive and negative externalities are linked to the way in which the units are interconnected and explain the stakeholder’s strong resistance to change, and their behaviors. These characteristics explain why organizational transformations are difficult to plan and manage.

Next, we consider organizational ambidexterity as a theory of the initiative and intentionality of strategic transformation linked to the information system [ORE 13]: the management will put in place divergent structures, processes and cultures to exploit the existing capacities while at the same time exploring the construction of the new organization. This approach shows strategic transformation as an initiative that is both planned and emerging. Following the ambidextrous approach outlined above, we could speak of the “combination” or “simultaneity” of these two paradigms (planning and improvisation). We could see a combination in a contextual approach to ambidexterity (where planning and improvisation are inseparable, linked, combined, and become a composite material), but we could also see a simultaneity of these paradigms in sequential and structural approaches (where there is a dissociation of the two activities).

8.6. Exercise: TechOne: Big Data and the Cloud

Over half (51%) of those surveyed [PRI 16] stated that they use Big Data to map potential threats (both external hackers and malicious employees) and to identify incidents. Big Data, however, is a major challenge for many companies. It requires vast storage capacity and also experienced specialists to develop algorithms and sophisticated analytical applications. The shortage of cyber security specialists and also budgetary constraints can be the brakes to implementing advanced solutions in terms of Big Data.

TechOne’s information system security manager, Alain Richard, believes that Big Data and intelligence on threats are needed to alert the top management of TechOne to risk and to help them understand the tactics and the operating mode of their adversaries. In fact, TechOne operates several patents in the field of biotechnology, and Alain Richard intends to rapidly implement a solution in order to better anticipate attacks and detect threats. He is thinking especially of Big Data and its ability to have a single source of correlated data across the company as a whole, which can be managed in real time. Alain Richard is thinking of hosting his Big Data solution on a public cloud (PaaS).

The computer power and storage of the cloud packages on the market (Amazon, Microsoft, etc.) will enable TechOne to monitor significant volumes of data, facilitating the identification of suspicious activities. The data are multiple: traces and logs from TechOne’s information system applications, network probes, firewalls and supervision probes set up within the IT infrastructure. Big Data will make it possible to compare all network activities and evaluate them permanently, to some extent constituting an advanced SIEM (Security Information and Event Management) system. When a new threat is identified, data analysis enables prioritization of responses according to the impact on business data.

Test your skills

- 1) Does Big Data bring a competitive advantage to TechOne in this case? What is its contribution to the business?

- 2) Is the public cloud a safe place to store sensitive company data? What are the advantages and disadvantages of the solution proposed by Alain Richard?