A cat and a dog shouldn't share a bed. Neither should integers and floats.

A cat and a dog shouldn't share a bed. Neither should integers and floats.

Thanks for picking up the book! This means you care for Generics. This is similar to dropping a plastic bag in favor of our lonely planet.

We are living in an interesting era, where more and more applications are data driven. To store these different kinds of data, we need several data structures. Although the actual piece of data is different, that doesn't always necessarily mean that the type of data is different. For example, consider the following situations:

Let's say, we have to write an application to pull in tweets and Facebook wall updates for given user IDs. Although these two result sets will have different features, they can be stored in a similar list of items. The list is a generic list that can be programmed to store items of a given type, at compile time, to ensure type safety. This is also known as parametric polymorphism.

In this introductory chapter, I shall give you a few reasons why Generics is important.

Here is an interesting analogy. Assume that there is a model hand pattern:

If we fill the pattern with clay, we get a clay-modeled hand. If we fill it with bronze, we get a hand model replica made of bronze. Although the material in these two hand models are very different, they share the same pattern (or they were created using the same algorithm, if you would agree to that term, in a broader sense).

Extrapolating the algorithm part, let's say we have to implement some sorting algorithm; however, data types can vary for the input. To solve this, you can use overloading, as follows:

//Overloaded sort methods

private int[] Sort(int[] inputArray)

{

//Sort input array in-place

//and return the sorted array

return inputArray;

}

private float[] Sort(float[] inputArray)

{

//Sort input array in-place

//and return the sorted array

return inputArray;

}However, you have to write the same code for all numeric data types supported by .NET. That's bad. Wouldn't it be cool if the compiler could somehow be instructed at compile time to yield the right version for the given data type at runtime? That's what Generics is about. Instead of writing the same method for all data types, you can create one single method with a symbolic data type. This will instruct the compiler to yield a specific code for the specific data type at runtime, as follows:

private T[] Sort<T>(T[] inputArray)

{

//Sort input array in-place

//and return the sorted array

return inputArray;

}

T is short for Type. If you replace T with anything, it will still compile; because it's the symbolic name for the generic type that will get replaced with a real type in the .NET type system at runtime.

So once we have this method, we can call it as follows:

int[] inputArray = { 1, 2, 0, 3 };

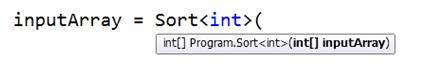

inputArray = Sort<int>(inputArray);However, if you hover your mouse pointer right after the first brace ((), you can see in the tooltip, the expected type is already int[], as shown in the following screenshot:

That's the beauty of Generics. As we had mentioned int inside < and >, the compiler now knows for sure that it should expect only an int[] as the argument to the

Sort<T> () method.

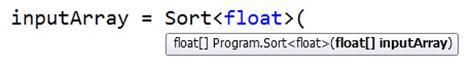

However, if you change int to float, you will see that the expectation of the compiler also changes. It then expects a float[] as the argument, as shown:

Now if you think you can fool the compiler by passing an integer array while it is asking for a float, you are wrong. That's blocked by compiler-time type checking. If you try something similar to the following:

You will get the following compiler error:

Argument 1: cannot convert from 'int[]' to 'float[]'

This means that Generics ensures strong type safety and is an integral part of the .NET framework, which is type safe.

The previous example was about a sorting algorithm that doesn't change with data type. There are other things that become easier while dealing with Generics.

There are broadly two types of operations that can be performed on a list of elements:

Adding some elements at the front and deleting elements at an index are a couple of examples of location-centric operations on a list of data. In such operations, the user doesn't need to know about the data. It's just some memory manipulation at best.

However, if the request is to delete every odd number from a list of integers, then that's a data-centric operation. To be able to successfully process this request, the method has to know how to determine whether an integer is odd or not. This might sound trivial for an integer; however, the point is the logic of determining whether an element is a candidate for deletion or not, is not readily known to the compiler. It has to be delegated.

Before Generics appeared in .NET 2.0, people were using (and unfortunately these are still in heavy use) non-generic collections that are capable of storing a list of objects.

As an object sits at the top of the hierarchy in the .NET object model, this opens floodgates. If such a list exists and is exposed, people can put in just about anything in that list and the compiler won't complain a bit, because to the compiler everything is fine as they are all objects.

So, if a loosely typed collection such as ArrayList is used to store objects of type T, then for any data-centric operation, these must be down-casted to T again. Now, if somehow an entry that is not T, is put into the list, then this down-casting will result in an exception at runtime.

Suppose, I want to maintain a list of my students, then we can do that by using ArrayList to store a list of such Student objects:

class Student

{

public char Grade

{

get; set;

}

public int Roll

{

get; set;

}

public string Name

{

get; set;

}

}

//List of students

ArrayList studentList = new ArrayList();

Student newStudent = new Student();

newStudent.Name = "Dorothy";

newStudent.Roll = 1;

newStudent.Grade = 'A';

studentList.Add(newStudent);

newStudent = new Student();

newStudent.Name = "Sam";

newStudent.Roll = 2;

newStudent.Grade ='B';

studentList.Add(newStudent);

foreach (Object s in studentList)

{

//Type-casting. If s is anything other than a student

//or a derived class, this line will throw an exception.

//This is a data centric operation.

Student currentStudent = (Student)s;

Console.WriteLine("Roll # " + currentStudent.Roll + " " + currentStudent.Name + " Scored a " + curr entStudent.Grade);

}All this might look kind of okay, because we have been taking great care not to put anything else in the list other than Student objects. So, while we de-reference them after boxing, we don't see any problem. However, as the ArrayList can take any object as the argument, we could, by mistake, write something similar to the following:

studentList.Add("Generics"); //Fooling the compilerAs ArrayList is a loosely typed collection, it doesn't ensure compile-time type checking. So, this code won't generate any compile-time warning, and eventually it will throw the following exception at runtime when we try to de-reference this, to put in a Student object.

Then, it will throw an InvalidCastException:

What the exception in the preceding screenshot actually tells us is that Generics is a string and it can't cast that to Student, for the obvious reason that the compiler has no clue how to convert a string to a Student object.

Unfortunately, this only gets noticed by the compiler during runtime. With Generics, we can catch this sort of error early on at compile time.

Following is the generic code to maintain that list:

//Creating a generic list of type "Student".

//This is a strongly-typed-collection of type "Student".

//So nothing, except Student or derived class objects from Student

//can be put in this list myStudents

List<Student> myStudents = new List<Student>();

//Adding a couple of students to the list

Student newStudent = new Student();

newStudent.Name = "Dorothy";

newStudent.Roll = 1;

newStudent.Grade = 'A';

myStudents.Add(newStudent);

newStudent = new Student();

newStudent.Name = "Sam";

newStudent.Roll = 2;

newStudent.Grade = 'B';

myStudents.Add(newStudent);

//Looping through the list of students

foreach (Student currentStudent in myStudents)

{

//There is no need to type cast. Because compiler

//already knows that everything inside this list

//is a Student.

Console.WriteLine("Roll # " + currentStudent.Roll + " " +currentStudent.Name + " Scored a " + currentStudent.Grade);

}The reasons mentioned earlier are the basic benefits of Generics. Also with Generics, language features such as LINQ and completely new languages such as F# came into existence. So, this is important. I hope you are convinced that Generics is a great programming tool and you are ready to learn it.

In the .NET Framework, everything is an object so it's okay to throw in anything to the non-generic loosely typed collection such as ArrayList, as shown in the previous example. This means we have to box (up-cast to object for storing things in the Arraylist; this process is implicit) and unbox (down-cast the object to the desired object type). This leads to slower code.

Here is the result of an experiment. I created two lists, one ArrayList and one List<int> to store integers:

And following is the data that drove the preceding graph:

|

ArrayList |

List<T> |

|---|---|

|

1323 |

185 |

|

1303 |

169 |

|

1327 |

172 |

|

1340 |

169 |

|

1302 |

172 |

The previous table mentions the total time taken in milliseconds to add 10,000,000 elements to the list. Clearly, generic collection is about seven times faster.

Look around. If you care to develop any non-trivial application, you are better off using some of the APIs built for the specific job at hand. Most of the APIs available rely heavily on strong typing and they achieve this through Generics. We shall discuss some of these APIs (LINQ, PowerCollections, C5) that are being predominantly used by the .NET community in this book.

So far, I have been giving you reasons to learn Generics. At this point, I am sure, you are ready to experiment with .NET Generics. Please check out the instructions in the next section to install the necessary software if you don't have it already.

If you are already running any 2010 version of Visual Studio that lets you create C# windows and console projects, you don't have to do anything and you can skip this section.

You can download and install the Visual Studio Trial from http://www.microsoft.com/download/en/details.aspx?displaylang=en&id=12752.

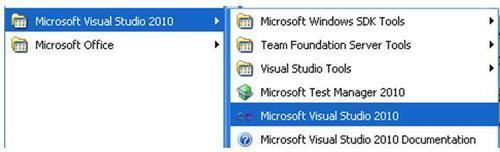

Once you are done, you should see the following in your program menu:

After this, start the program highlighted in the preceding screenshot Microsoft Visual Studio 2010.

Then go to the File menu to create a console project:

Now, once that is created, make sure the following namespaces are available:

If these are available, you have done the right setup. Congratulations!

My objective for this chapter was to make sure you get why Generics is important. Following are the points again in bullets:

It ensures compile-time type checking, so type safety is ensured.

It can yield the right code for the data type thrown at it at runtime, thus saving us a lot of typing.

It is very fast (about seven times) compared to its non-generic cousins for value types.

It is everywhere in the .NET ecosystem. API/framework developers trust the element of least surprise and they know people are familiar with Generics and their syntax. So they try to make sure their APIs also seem familiar to the users.

In the end, we did an initial setup of the environment; so we are ready to build and run applications using .NET Generics. From the next chapter, we shall learn about .NET Generic containers and classes. In the next chapter, we shall discuss the Generic container List<T> that will let you store any type of data in a type safe way. Now that you know that's important, let's go there.