Chapter 1. Introducing ASP.NET AJAX

In this chapter:

- An overview of Ajax programming

- The ASP.NET AJAX architecture

- The client-centric development model

- The server-centric development model

- A tour of ASP.NET AJAX

Ajax has revolutionized the way users interact with web pages. Gone are the days of frustrating page refreshes, losing your scroll position on a page, and working in the redraw-refresh paradigm of traditional web applications. In its place is the next generation of web applications: Ajax applications, whose characteristics include smoother page updates; continuous, fluid interaction; and visually appealing, rich interfaces.

The term Ajax, which stands for Asynchronous JavaScript and XML, was coined to describe this new approach to web development. Although most users aren’t familiar with the acronym, they’re certainly familiar with its benefits. Sites like Google Maps, Live.com, and Flickr are just a few examples of recent applications that are leading the way through this new frontier. Each of them offers slightly different services, but all share the same goal: to provide a rich user experience that is personalized, engaging, and supported across all major browsers.

Unfortunately, using these next-generation web applications is far more trivial than authoring them. Ajax applications require a different approach to thinking about web solutions. This paradigm shift requires more discipline and knowledge of client-side scripting along with the conscious decision to deliver a smarter and more intuitive application to the browser. In addition, although it’s been around for a while, Ajax is still relatively new to web developers, and techniques for patterns, guidelines, and best practices are still being discovered and refined. To assist in this transition, the Microsoft ASP.NET AJAX framework encapsulates a rich set of controls, scripts, and resources that empowers you to more easily craft the next generation of web applications.

The goal in this introductory chapter is to get you started on developing applications with the ASP.NET AJAX framework. To whet your appetite, we’ll go through a whirlwind tour of the most basic and commonly used components and follow up with a few quick examples that demonstrate their use. Subsequent chapters examine each of these components in more detail and reveal how things work under the hood. But before you can discover the ASP.NET AJAX framework, you must first understand what Ajax is and how we got here.

1.1. What is Ajax?

Ajax is an approach or pattern to web development that uses client-side scripting to exchange data with a web server. This approach enables pages to be updated dynamically without causing a full page refresh to occur (the dream, we presume, of every web developer). As a result, the interaction between the user and the application is uninterrupted and remains continuous and fluid. Some consider this approach to be a technology rather than a pattern. Instead, it’s a combination of related technologies used together in a creative way.

The result of bringing these technologies together is nothing new. Techniques for asynchronous loading of content on the Web can be dated as far back as Internet Explorer 3 (also known as the Jurassic years of web development) with the introduction of the IFRAME element. Shortly after, the release of Internet Explorer 5 introduced the XMLHttpRequest ActiveX object, which made possible the exchange of data between the client and server through web browser scripting languages.

Note

Some credit remote scripting as the precursor to Ajax development. Prior to the XMLHttpRequest object, remote scripting allowed scripts running in a browser to exchange information with a server. For more about remote scripting, read http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Remote_Scripting.

Even with the release of the XMLHttpRequest object, and with applications like Outlook Web Access taking advantage of these techniques, it wasn’t until the release of Google Maps that Ajax was noticed by the masses.

You now have a high-level understanding of Ajax and how it came to be, but we haven’t discussed the technologies that make up the pattern or how the ASP.NET AJAX framework fits into the picture. It’s important that we spend a little more time fully explaining how Ajax works and discussing the technologies that form it.

1.1.1. Ajax components

As we previously mentioned, the Ajax programming pattern consists of a set of existing technologies brought together in an imaginative way, resulting in a richer and more engaging user experience. The following are the main pillars of the Ajax programming pattern and the role they play in its model:

- JavaScript— A scripting language that is commonly hosted in a browser to add interactivity to HTML pages. Loosely based on the C programming language, JavaScript is the most popular scripting language on the Web and is supported by all major browsers. Ajax applications are built in JavaScript.

- Document Object Model (DOM)— Defines the structure of a web page as a set of programmable objects that can be accessed through JavaScript. In Ajax programming, the DOM is leveraged to effectively redraw portions of the page.

- Cascading Style Sheets (CSS)— Provides a way to define the visual appearance of elements on a web page. CSS is used in Ajax applications to modify the exterior of the user interface interactively.

- XMLHttpRequest— Allows a client-side script to perform an HTTP request. Ajax applications use the XMLHttpRequest object to perform asynchronous requests to the server as opposed to performing a full-page refresh or postback.

Note

The name of the XMLHttpRequest object is somewhat misleading because data can be transferred in the form of XML or other text-based formats. The ASP.NET AJAX framework relies heavily on a format called JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) to deliver data to and from the server. Examples of JSON and how the ASP.NET AJAX framework uses it are scattered throughout this book. You can find a more thorough explanation of JSON in chapter 3.

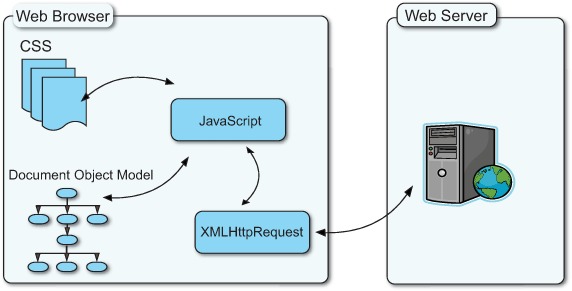

Listing the technologies is easy; but understanding how they work together, complement each other, and deliver a better user experience is the objective. Figure 1.1 illustrates how these technologies interact with one another from the browser.

Figure 1.1. Ajax components. The technologies used in the Ajax pattern complement each to deliver a richer and smarter application that runs on the browser.

In an Ajax-enabled application, you can think of JavaScript as the glue that holds everything together. When data is needed, the XMLHttpRequest object is used to make a request to the server. When the data is returned, the DOM and CSS are leveraged to update the browser’s user interface dynamically.

Tip

You can find a collection of Ajax design patterns at http://ajaxpatterns.org.

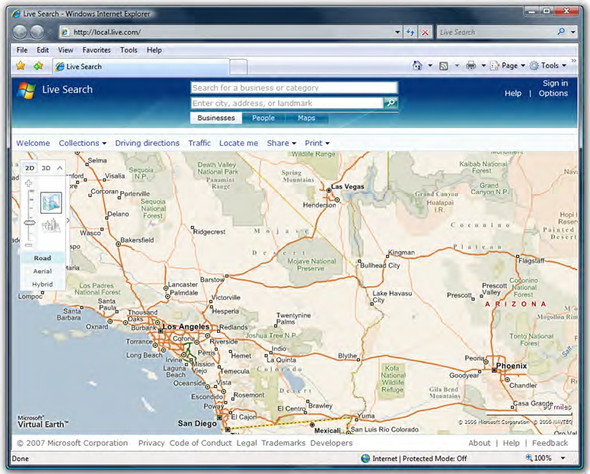

To see this in action, visit the maps page on the Windows Live site at http://local.live.com (see figure 1.2). Notice the interactive map and how clicking and dragging the map updates the contents on the page without causing a full page refresh to occur. The tiles for the map are retrieved in the background via the XMLHttpRequest object; the user is granted continuous interaction with the application in the process. Take some time to discover what the site has to offer, and note how fluid and responsive the page actions appear. Using the ASP.NET AJAX framework, these are the types of intuitive and interactive applications that you’ll build throughout this book.

Figure 1.2. The Windows Live site is an excellent example of what can be accomplished with the ASP.NET AJAX framework.

The maps on Live.com rely heavily on retrieving data asynchronously so users can continue to interact with the applications. This key pattern is perhaps the most important thing to understand about Ajax.

1.1.2. Asynchronous web programming

The A in Ajax stands for asynchronous; this is a key behavior in the Ajax programming pattern. Asynchronous means not synchronized or not occurring at the same time. To better understand this, let’s take a real-life example. If you go to Starbucks and walk up to the counter, you present the cashier with your order (a tall, iced café mocha for David, in case you were wondering). The cashier marks an empty cup with details of the order and places it into a queue. The queue, in this instance, is literally a stack of other empty cups that represent pending orders waiting to be fulfilled. This process decouples the cashier from the individuals (baristas, if you want to get fancy) who prepare the drinks. With this approach, the cashier can continue to interact with the customers while orders are being processed at a different time—asynchronously. In the end, Starbucks maximizes its output and significantly improves the customer experience.

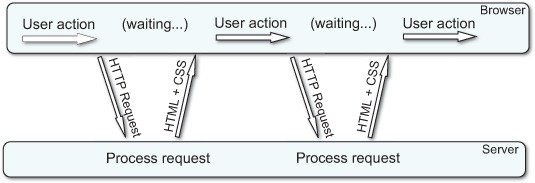

Now, let’s examine what things would be like with a more traditional approach—in a synchronous process. If only one person were working in the shop that day, they would have to take on the chores and responsibilities of both the cashier and barista. A customer would place an order, and the next customer would be forced to wait for the previous order to be completed before they could place their own. This less efficient process is how traditional web applications work: They take away the continuous interaction and force users to wait for a particular action to be completed. Figure 1.3 demonstrates the flow of a traditional web application in a synchronous manner.

Figure 1.3. Traditional web applications behave in a synchronous manner and take away all interaction from the user during HTTP requests.

Normally, a user action such as clicking a button on a form invokes an HTTP request back to the web server. The server then processes the request, possibly doing some calculations or performing a few database operations; and then returns back to the client a whole new page to render. Technically, this makes a lot of sense—web pages are stateless by nature, and because all the logic about the application typically resides on the server, the browser is just used to display the interface. The server goes through the entire page lifecycle again and returns to the browser the HTML, CSS, and any other resources it needs to refresh the page. Unfortunately, this doesn’t present the user with a desirable experience. Instead, they’re exposed to a stop-start-stop pattern where they temporarily (and unwillingly) lose interaction with the page and are left waiting for it to be updated.

Note

In ASP.NET, when a form posts data back to itself (or even to another page), it’s called a postback. During this process, the current state of the page and its controls are sent to the server for processing. The postback mechanism is relied on to preserve the state of the page and its server controls. This process causes the page to refresh and is costly because of the amount of data sent back and forth to the server and the loss of interaction for the user.

An Ajax-enabled application works differently, mainly by eliminating the intermittent nature of interaction with the introduction of an Ajax agent placed between the client and server. This agent communicates with the server asynchronously, on behalf of the client, to make the HTTP request to the server and return the data needed to update the contents of the page. Figure 1.4 demonstrates this asynchronous model.

Figure 1.4. The asynchronous web application model leverages an Ajax engine to make an HTTP request to the server.

Notice that in the asynchronous model, a call originating from JavaScript is made to the Ajax engine instead of the server to retrieve and receive data. At the core of the Ajax engine is the XMLHttpRequest object, which we’ll look at next to solidify your understanding of how Ajax works.

1.1.3. The XMLHttpRequest object

The XMLHttpRequest object is at the heart of Ajax programming because it enables JavaScript to make requests to the server and process the responses. It was delivered in the form of an ActiveX object when released in Internet Explorer 5, and it’s supported in most current browsers. Other browsers (such as Safari, Opera, Firefox, and Mozilla) deliver the same functionality in the form of a native JavaScript object. Ironically, Internet Explorer 7 now implements the object in native JavaScript as well, although differences between browsers remain. The fact that there are different implementations of the object based on browsers and their versions requires you to write browser-sensitive code when instantiating it from script. Listing 1.1 uses a technique called object detection to determine which XMLHttpRequest object is available.

Listing 1.1. Instantiating the XMLHttpRequest object

var xmlHttp = null;

if (window.XMLHttpRequest) { // IE7, Mozilla, Safari, Opera, etc.

xmlHttp = new XMLHttpRequest();

} else if (window.ActiveXObject) {

try{

xmlHttp = new ActiveXObject("Microsoft.XMLHTTP"); //IE 5.x, 6

}

catch(e) {}

}

Now that the object has been instantiated, you can use it to make an asynchronous request to a server resource. To keeps things simple, you can make a request to another page called Welcome.htm, the contents of which are shown in listing 1.2.

Listing 1.2. Welcome.htm

<!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Transitional//EN"

"http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-transitional.dtd">

<html xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml" >

<head>

<title>Welcome</title>

</head>

<body>

<div>Welcome to ASP.NET AJAX In Action!</div>

</body>

</html>

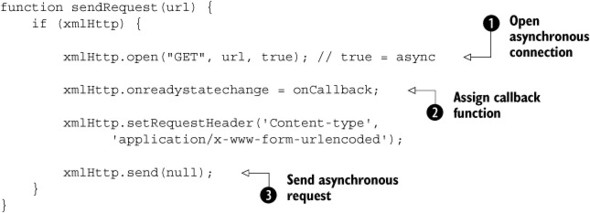

Welcome.htm is pretty minimal and contains some static text welcoming you to the book. You make the asynchronous request with a few more lines of code that you wrap in a function called sendRequest (see listing 1.3).

Listing 1.3. Sending an asynchronous request

The sendRequest method takes as a parameter the URL to which you’ll be making an HTTP request. Next, it ![]() opens a connection with the asynchronous flag set to true. After the connection is initialized, it

opens a connection with the asynchronous flag set to true. After the connection is initialized, it ![]() assigns the onreadystatechange property of the XMLHttpRequest object to a local function called onCallback. Remember, this will be an asynchronous call, which means you don’t know when it will return. A callback function is given

so you can be notified when the request is complete or its status has been updated. After specifying the content type in the

request header, you call the

assigns the onreadystatechange property of the XMLHttpRequest object to a local function called onCallback. Remember, this will be an asynchronous call, which means you don’t know when it will return. A callback function is given

so you can be notified when the request is complete or its status has been updated. After specifying the content type in the

request header, you call the ![]() send method to transmit the HTTP request to the server.

send method to transmit the HTTP request to the server.

If you go back to the earlier Starbucks example, the open command is similar to placing the order, and the send command is like the order being placed in the queue. The callback function is the unique name associated with your order—typically your name. Another interesting tidbit is that in IE, only two connections can be opened at a time, which is the equivalent of having two cashiers available to take the orders.

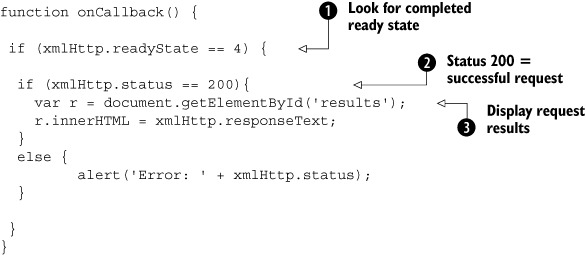

When the status of the request changes and the callback function is invoked, the final step is to check the status and update the user interface with the contents returned from Welcome.htm (see listing 1.4).

Listing 1.4. The callback function gets called every time the ready state changes for the asynchronous request.

The status of the request is returned in the readyState ![]() property of the XMLHttpRequest object. The value 4 indicates that the request has completed. Next, the response from the server

property of the XMLHttpRequest object. The value 4 indicates that the request has completed. Next, the response from the server ![]() must be checked to confirm that everything was successful. Status code 200 is designated in the HTTP protocol to indicate

that a request has succeeded. Finally, the innerHTML of a span element is updated to reflect the contents in the response

must be checked to confirm that everything was successful. Status code 200 is designated in the HTTP protocol to indicate

that a request has succeeded. Finally, the innerHTML of a span element is updated to reflect the contents in the response ![]() . Listing 1.5 shows the complete code for this example.

. Listing 1.5 shows the complete code for this example.

Listing 1.5. Using the XMLHttpRequest control to asynchronously retrieve data

<%@ Page Language="C#" AutoEventWireup="true"

CodeFile="XmlHttpRequest.aspx.cs"

Inherits="CH_01_XmlHttpRequest" %>

<!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Transitional//EN"

"http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-transitional.dtd">

<html xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml" >

<head runat="server">

<title>ASP.NET AJAX In Action - XMLHttpRequest</title>

</head>

<body>

<form id="form1" runat="server">

<div>

<span id="results">Loading...</span>

</div>

</form>

<script type="text/javascript">

var xmlHttp = null;

window.onload = function() {

loadXmlHttp();

sendRequest("Welcome.htm");

}

function loadXmlHttp() {

if (window.XMLHttpRequest) { // IE7, Mozilla, Safari, Opera

xmlHttp = new XMLHttpRequest();

} else if (window.ActiveXObject) {

try{

xmlHttp = new ActiveXObject("Microsoft.XMLHTTP"); //IE 5.x, 6

}

catch(e) {}

}

}

function sendRequest(url) {

if (xmlHttp) {

xmlHttp.open("GET", url, true); // true = async

xmlHttp.onreadystatechange = onCallback;

xmlHttp.setRequestHeader('Content-type',

'application/x-www-form-urlencoded'),

xmlHttp.send(null);

}

}

function onCallback() {

if (xmlHttp.readyState == 4) {

if (xmlHttp.status == 200){

var r = document.getElementById('results'),

r.innerHTML = xmlHttp.responseText;

}

else {

alert('Error: ' + xmlHttp.status);

}

}

}

</script>

</body>

</html>

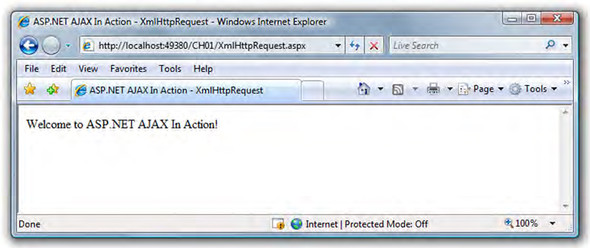

Figure 1.5 shows the output that results when you execute the example code.

Figure 1.5. A simple asynchronous request to another page

The example we just walked through demonstrates how to leverage the XMLHttpRequest object to make a simple asynchronous HTTP request to another page on the server. When the request is completed, you display the results on the page by dynamically updating the contents of one of its UI elements—a span. There is a lot more to the XMLHttpRequest object that we didn’t cover; we barely scratched the surface. The point of this exercise was to introduce you to the basics of the Ajax programming pattern. You should recognize some of the issues that arise with Ajax development, such as cross-browser compatibility and the need for a lot of plumbing code to execute requests to the server. This takes us into the next section, which discusses other issues and complexities in Ajax development.

1.1.4. Ajax development issues

Without a toolkit or framework to leverage, developing Ajax-enabled applications is no trivial task. Several development issues arise, the most obvious of which is browser compatibility. Aside from the different implementations of the XMLHttpRequest object, each browser also implements a slightly different version of the DOM. Keeping up with changes between browsers and managing browser detection can be a tedious and error-prone process. One of the goals of a toolkit or framework is to abstract away the complexities and discrepancies between browsers so you can use a simple and consistent set of APIs to perform the same operations.

Another challenge is the requirement for a strong grasp of the JavaScript language. JavaScript isn’t inherently a complex language; however, many ASP.NET developers lack expertise in it. In addition, JavaScript doesn’t offer the object-oriented, type-safe features that .NET developers have grown accustomed to with C#, VB.NET, and other .NET languages. Concepts such as inheritance, interfaces, and events can be simulated in JavaScript but are left to you to implement. Without a framework, this portion of JavaScript remains for you to master in order to make any progress. Debugging and the lack of support for client-scripting languages in integrated development environments (IDEs) adds to the complexity and challenges.

By now, you probably see the direction we’re headed: In almost every case, it’s wiser to leverage a framework or toolkit when developing Ajax-enabled applications rather than deal with these complexities on your own. We’re certain there are simple situations where coding something quickly with the XMLHttpRequest object can get the job done, but this book’s aspirations are much greater. With that said, it’s time to look at ASP.NET AJAX and what it has to offer as a framework and library.

1.2. ASP.NET AJAX architecture

The ASP.NET AJAX framework enables developers to create rich, interactive, highly personalized web applications that are cross-browser compliant. At first glance, you may think this sounds like another way of saying that the framework is an Ajax library. The truth is, it’s primarily an Ajax library, but it offers many other features that can increase the productivity and quality of your web applications. This will make more sense once we examine the architecture, shown in figure 1.6.

Figure 1.6. The ASP.NET AJAX architecture spans both the client and server.

The first thing you may notice about the architecture of the ASP.NET AJAX framework is that it spans both the client and server. In addition to a set of client-side libraries and components, there is also a great deal of support on the server side, with ASP.NET server controls and services.

We’ll explore both sides of the framework heavily throughout the book, beginning with the client framework.

1.2.1. Client framework

One of the nice things about the client framework is that the core library isn’t reliant on the server components. The core library can be used to develop applications built in Cold Fusion, PHP, and other languages and platforms. With this flexibility, the architecture can be divided logically into two pieces: the client framework and the server framework. Understanding how things work in the client framework is essential even for server-side developers, because this portion brings web pages to life. At the core is the Microsoft Ajax Library.

Microsoft Ajax Library

As we stated previously, the heart of the client framework is the Microsoft Ajax Library, also known as the core library. The library consists of a set of JavaScript files that can be used independently from the server features. We’ll ease into the core library by explaining the intentions of each of its pieces or layers, beginning with its foundation: the type system.

Note

In previous versions of ASP.NET AJAX, when it had the codename Atlas, the core library was referred to as the Client Script Library.

The goal of the type system is to introduce familiar object-oriented programming concepts to JavaScript—like classes, inheritance, interfaces, and event-handling. This layer also extends existing JavaScript types. For example, the String and Array types in JavaScript are both extended to provide added functionality and a familiarity to ASP.NET developers. The type system lays the groundwork for the rest of the Ajax core library.

Next up in the core library is the Components layer. Built on top of the type system’s solid foundation, the Components layer does a lot of the heavy lifting for the core library. This layer provides support for JSON serialization, network communication, localization, DOM interaction, and ASP.NET application services like authentication and profiles. It also introduces the notion of building reusable modules that can be categorized as controls and behaviors on a page.

This brings us to the top layer in the library: the Application layer. A more descriptive title is the application model. Similar to the page lifecycle in ASP.NET, this layer provides an event-driven programming model that you can use to work with DOM elements, components, and the lifecycle of an application in the browser.

HTML, JavaScript, and XML Script

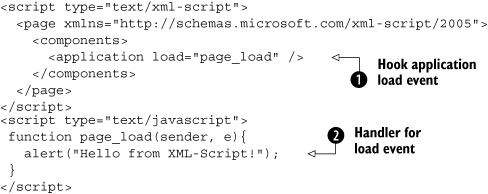

ASP.NET AJAX-enabled web pages are written in HTML, JavaScript, and a new XML-based, declarative syntax called XML Script. This provides you with more than one option for authoring client-side code—you can code declaratively with XML Script and imperatively with JavaScript. Elements declared in XML Script are contained in a new script tag:

<script type="text/xml-script">

The browser can detect the script tag but doesn’t have a mechanism for processing the xml-script type. Instead, the JavaScript files from the ASP.NET AJAX framework can parse the script and create an instance of components and controls on the page. Listing 1.6 provides a snippet of how XML Script is used to display a message after the page has loaded.

Listing 1.6. XML-Script: a declarative alternative for developing Ajax-enabled pages

In this example, a JavaScript function called ![]() page_load is declaratively attached to the load event in the page lifecycle. Executing this page invokes the

page_load is declaratively attached to the load event in the page lifecycle. Executing this page invokes the ![]() page_load function after the load event to display a message box on the client.

page_load function after the load event to display a message box on the client.

XML Script and some other features in the framework are delivered in a separate set of resources called the ASP.NET Futures. These features are currently in the Community Technology Preview (CTP) status. CTP reflects the current state of a product that is still undergoing possible changes. In this case, the ASP.NET Futures CTP is an extension of the core ASP.NET AJAX framework that will eventually be migrated into the core package. The good news is that we’ll cover XML Script and other features in great detail throughout the book so nothing is left out.

Why choose XML Script over JavaScript or vice versa? Sometimes the answer comes down to your preference; some developers prefer the elegance of a markup language over script, but others feel more comfortable and in control coding only JavaScript. These approaches can coexist, and both have pros and cons that we’ll discuss in their respective chapters of the book.

ASP.NET AJAX service proxies

The client framework offers the ability to call web services from JavaScript via a set of client-side proxies that are generated from the server. These proxies can be leveraged much like a web reference in managed .NET code.

Note

A proxy is a class that operates as an interface to another thing—in this case, a web service. For more on the proxy pattern, visit the Wikipedia page at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proxy_pattern.

We’ll take a more thorough look at how this works later in the chapter. If this is something you’d like to know more about now, feel free to jump to chapter 5, where we discuss working with services and making asynchronous calls in greater detail.

Now that you have a high-level understanding of the client framework, let’s move on to the server framework to complete your understanding of the overall architecture.

1.2.2. Server framework

Built on top of ASP.NET 2.0 is a valuable set of controls and services that extend the existing framework with Ajax support. This tier of the server framework is called the ASP.NET AJAX server extensions. The server extensions are broken into three areas: server controls, the web services bridge, and the application services bridge. Each of these components interacts closely with the application model on the client to improve the interactivity of existing ASP.NET pages.

ASP.NET AJAX server controls

The new set of server controls adds to the impressive arsenal of tools in the ASP.NET toolbox and is predominantly driven by two controls. The first of these controls is the ScriptManager, which is considered the brains of an Ajax-enabled page. One of the many responsibilities of the ScriptManager is orchestrating the regions on the page that are dynamically updated during asynchronous postbacks. The second control, named the UpdatePanel, is used to define the regions on the page that are designated for partial updates. These two controls work together to greatly enhance the user experience by replacing traditional postbacks with asynchronous postbacks. This results in regions of the page being updated incrementally rather than all at once with a full page refresh.

The remaining components of the server extensions are services that bridge the gap between the client and server.

Web services bridge

Typically, web applications are limited to resources on their local servers. Aside from a few external resources, like images and CSS files, applications aren’t granted access to resources that aren’t in the scope of the client application. To overcome these hurdles, the server extensions in the ASP.NET AJAX framework include a web services bridge that creates a gateway for you to call external web services from client-side script. This type of technology will be handy when we look at how to aggregate or consume data from third-party services.

Application services bridge

Because ASP.NET AJAX is so tightly integrated with ASP.NET, access to some of the application services like authentication and profile can be added to an existing application almost effortlessly. This feature enables tasks like verifying a user’s credentials and accessing their profile information to originate from the client script. This isn’t entirely necessary, but it adds to the overall user experience.

Now that you have a general idea of what pieces form the framework, we can begin to examine how they’re leveraged effectively. This leads to the examination of two development scenarios.

1.2.3. Client-centric development model

The flexible design of the architecture naturally provides two development scenarios. The first scenario is primarily implemented on the client side and is known as the client-centric development model. The second is developed mainly on the server side and is identified as the server-centric development model. It’s worth taking some time to understand how these models work and when to use each of them.

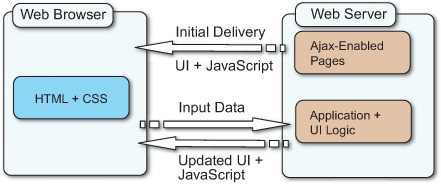

In the client-centric model, the presentation tier is driven from the client-script using DHTML and JavaScript. This means a smarter and more interactive application is delivered from the server to the browser when the page is first loaded. Afterward, interaction between the browser application and the server is limited to retrieving the relevant data necessary to update the page. This model encourages a lot more interactivity between the user and the browser application, resulting in a richer and more intuitive experience. Figure 1.7 illustrates the client-centric development model.

Figure 1.7. The client-centric development model is driven by a smarter and more interactive application that runs on the browser.

The client-centric model is also ideal for mashups and applications that wish to fully exploit all the features DHTML has to offer.

Note

A mashup is a web application that consumes content from more than one external source and aggregates it into a seamless, interactive experience for the user.

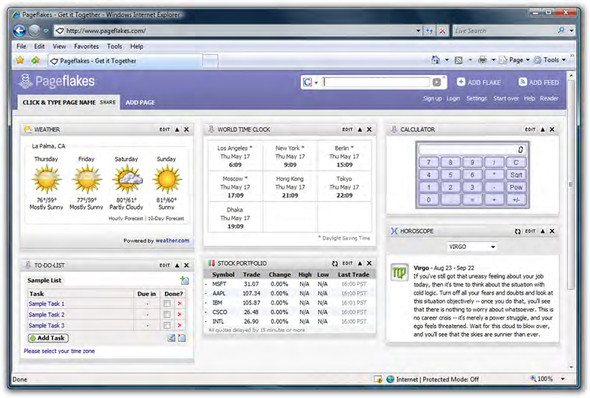

You’ll build a simple mashup in chapter 5, once you’ve delved deeper into the networking components of the framework. In the meantime, Pageflakes.com provides an excellent example of the rich content mashups can consume (see figure 1.8).

Figure 1.8. Pageflakes is a great example of how a mashup application consumes data from multiple resources to enrich the user experience.

An application like Pageflakes relies heavily on user interaction. In addition, the page needs to be light, effective, and mindful of system resources. For these reasons, a client-centric approach is the preferred model.

1.2.4. Server-centric development model

In the server-centric model, the application logic and most of the UI rationale remain on the server. Incremental changes for the UI are passed down to the browser application instead of the changes being made from the client-side script. This approach resembles the traditional ASP.NET page model, where the server renders the UI on each postback and sends back down to the browser a new page to render. The difference between this model and the traditional model in ASP.NET is that only the portions of the UI that need to be rendered are passed down to the browser application, rather than the whole page. As a result, interactivity and latency are both improved significantly. Figure 1.9 illustrates the nature of the server-centric development model.

Figure 1.9. The Server-Centric Development model passes down to the browser application portions of the page to update instead of a whole new page to refresh.

This approach appeals to many ASP.NET developers because it grants them the ability to keep the core UI and application logic on the server. It’s also attractive because of its transparency and ability to behave as a normal application if the user disables JavaScript in the browser. When you’re working with controls like the GridView and Repeater in ASP.NET, the server-centric model offers the simplest and most reliable solution.

1.2.5. ASP.NET AJAX goals

After examining the architecture and features in the framework, you can easily deduce the goals and intentions that ASP.NET AJAX sets out to accomplish:

- Easy-to-use, highly productive framework— The main objective is to simplify the efforts of adding Ajax functionality to web applications. This is accomplished by providing a rich client library and a comprehensive set of server controls that are easy to use and integrate into existing applications.

- Server programming model integration— Server controls provide ASP.NET developers with a familiar paradigm for developing web applications. These controls emit the JavaScript needed to Ajax-enable a page with little effort or knowledge of JavaScript and the XMLHttpRequest object.

- World-class tools and components— Components and tools built on top of the framework not only extend the framework but also provide the development community with a rich collection of tools to leverage and build on. This includes tools for debugging, tracing, and profiling.

- Cross-platform support— Support for Internet Explorer, Firefox, Safari, and Opera extracts away the hassle of dealing with browser differences and discrepancies.

These goals are what you’d expect from a framework: simplicity, extensibility, community involvement, and powerful tools. Let’s start using the framework!

1.3. ASP.NET AJAX in action

So far in this chapter, we’ve touched on the XMLHttpRequest object and some of the Ajax patterns used when developing richer, more interactive web applications. We’ve also examined the ASP.NET AJAX architecture and the different development scenarios that rationally emerge from its design. It’s time to apply some of this knowledge and walk through a few quick applications that demonstrate how to build pages with ASP.NET AJAX.

The following sections move rather quickly, because they’re intended to give you a whirlwind tour of the framework. Subsequent chapters will dissect and explain each of the topics more carefully. Let’s begin the tour.

1.3.1. Simple server-centric solution

As you sit comfortably in your cubicle, reading your daily emails, the all-mighty director of human resources appears before you and demands that you build a web application immediately (a situation akin to a Dilbert cartoon strip). The request is for an application that gives the user the ability to look up the number of employees in each department of the company. After presenting you with his demands and an impossibly short timeline, the HR director retreats to headquarters as you hastily begin your new assignment.

The first step in every ASP.NET web development endeavor is creating the initial website. To get started, launch Visual Studio 2005 (or the free Visual Web Developer 2005), and select the ASP.NET AJAX-Enabled Web Site template from the New Web Site dialog (see figure 1.10). This creates a site that references the ASP.NET AJAX assembly System.Web.Extensions.dll from the Global Assembly Cache (GAC). It also generates a complex web.config file that includes additional settings for integration with the ASP.NET AJAX framework.

Figure 1.10. The ASP.NET AJAX-Enabled Web Site template creates a website that references the ASP.NET AJAX assembly and configures the web.config file for Ajax integration.

The initial site created from the template is all you need for this example and for a majority of ASP.NET AJAX applications that you’ll build.

Tip

Details on how to install and configure the ASP.NET AJAX framework on a development machine are explained in appendix A. All examples in this book can also be built with the Visual Web Developer Express edition. For simplicity, we’ll defer to Visual Studio when we mention the development environment.

For the employee lookup logic, create a simple class called HumanResources.cs, and copy the code in listing 1.7.

Listing 1.7. A simple class that returns the number of employees in a department

using System;

public static class HumanResources

{

public static int GetEmployeeCount(string department)

{

int count = 0;

switch (department)

{

case "Sales":

count = 10;

break;

case "Engineering":

count = 28;

break;

case "Marketing":

count = 44;

break;

case "HR":

count = 7;

break;

default:

break;

}

return count;

}

}

The HumanResources class contains one method, GetEmployeeCount, which takes the department name as a parameter. It uses a simple switch statement to retrieve the number of employees in the department. (To keeps things simple, we hard-coded the department names and values.)

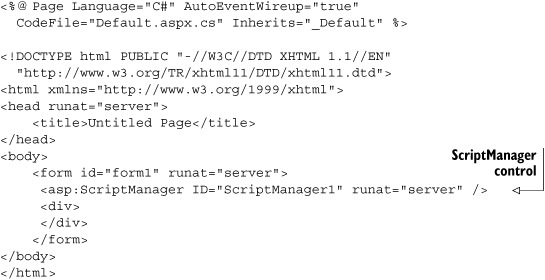

When you created the new website, a default page named Default.aspx was also generated. Listing 1.8 shows the initial version of the page.

Listing 1.8. Default page created by the ASP.NET AJAX-Enabled Web Site template

What’s different in this page from the usual default page created by Visual Studio is the addition of the ScriptManager control. We briefly defined the ScriptManager earlier in the chapter as the brains of an Ajax-enabled page. In this example, all you need to know about the ScriptManager is that it’s required to Ajax-enable a page—it’s responsible for delivering the client-side scripts to the browser and managing the partial updates on the page. If these concepts still sound foreign, don’t worry; they will make more sense once you start applying them.

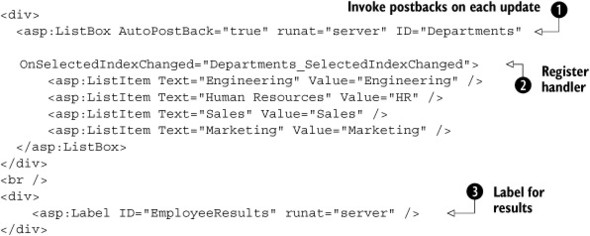

As it turns out, creating the application requested by HR is fairly trivial. Listing 1.9 shows the markup portion of the solution.

Listing 1.9. Setting AutoPostBack to true causes a postback and invokes the server-side code.

A ListBox is used to display the catalog of departments to choose from. The AutoPostBack property of the control is initialized to ![]() true so that any selection made invokes a postback on the form. This action fires the SelectedIndexChanged event and calls the

true so that any selection made invokes a postback on the form. This action fires the SelectedIndexChanged event and calls the ![]() Departments_SelectedIndexChanged handler in the code. At the bottom of the page is a Label control where

Departments_SelectedIndexChanged handler in the code. At the bottom of the page is a Label control where ![]() the results are displayed. To complete the application, you implement the UI logic that looks up the employee count for the

selected department in the code-behind file (see listing 1.10).

the results are displayed. To complete the application, you implement the UI logic that looks up the employee count for the

selected department in the code-behind file (see listing 1.10).

Listing 1.10. Retrieve the employee count and update the UI when a new department has been selected.

protected void Departments_SelectedIndexChanged(object sender,

EventArgs e)

{

EmployeeResults.Text = string.Format("Employee count: {0}",

HumanResources.GetEmployeeCount(Departments.SelectedValue));

}

When the application is launched and one of the departments is selected, it should look like figure 1.11.

Figure 1.11. The employee-lookup application before adding any Ajax support

The program works as expected: Selecting a department retrieves the number of employees and displays the results at the bottom of the page. The only issue is that the page refreshes each time a new department is chosen. Handling this is also trivial; you wrap the contents of the form in an UpdatePanel control (see listing 1.11).

Listing 1.11. UpdatePanel control, designating page regions that can be updated dynamically

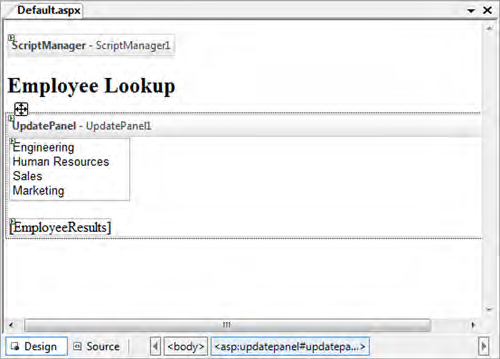

As an alternative, figure 1.12 shows what the solution looks like from the Design view in Visual Studio.

Figure 1.12. Using the Design view in Visual Studio provides a visual alternative to editing the layout and elements on the page.

By default, content placed in the ContentTemplate tag of the UpdatePanel control is updated dynamically when an asynchronous postback occurs. This addition to the form suppresses the normal postback that most ASP.NET developers are accustomed to and sends back to the server an asynchronous request that delivers to the browser the new UI for the form to render.

What do we mean when we say asynchronous postback? Most ASP.NET developers are familiar with only one kind of postback. With the UpdatePanel, the page still goes through its normal lifecycle, but the postback is marked as being asynchronous with some creative techniques that we’ll unveil in chapter 7. As a result, the page is handled differently during the lifecycle so that updates can be made incrementally rather than by refreshing the entire page. For now, you can see that adding this type of functionality is simple and transparent to the logic and development of the page.

The next time you run the page and select a department, the UI updates dynamically without a full page refresh. In summary, by adding a few new server controls on the page you’ve essentially eliminated the page from reloading itself and taking away any interaction from the user.

1.3.2. UpdateProgress control

You show the application to the director of human resources, who is impressed. However, he notices that when he goes home and tries the application again, with a slow dial-up connection, it takes significantly longer for the page to display the results. The delay in response time confuses the director and initially makes him wonder if something is wrong with the application.

Before the introduction of Ajax, a page being refreshed was an indication to most users that something was being processed or that their actions were accepted. Now, with the suppression of the normal postback, users have no indication that something is happening in the background until it’s complete. They need some sort of visual feedback notifying them that work is in progress.

The UpdateProgress control offers a solution to this problem. Its purpose is to provide a visual cue to the user when an asynchronous postback is occurring. To please the HR director, you add the following snippet of code to the end of the page:

<asp:UpdateProgress ID="UpdateProgress1" runat="server">

<ProgressTemplate>

<img src="images/indicator.gif" /> Loading ...

</ProgressTemplate>

</asp:UpdateProgress>

When you run the application again, the visual cue appears when the user selects a new department (see figure 1.13).

Figure 1.13. It’s generally a good practice to inform users that work is in progress during an asynchronous update.

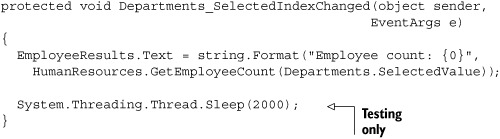

If you’re running this application on your local machine, chances are that the page updates fairly quickly and you may not get to see the UpdateProgress control working. To slow the process and see the loading indicator, add to the code the Sleep command shown in listing 1.12.

Listing 1.12. Adding a Sleep command to test the UpdateProgress control.

Warning

Don’t call the Sleep method in production code. You use it here only for demonstration purposes so you can see that the UpdateProgress control is working.

When used effectively with the UpdatePanel, the UpdateProgress control is a handy tool for relaying visual feedback to the user during asynchronous operations. We discuss best practices throughout the book; in this case, providing visual feedback to the user is strongly encouraged.

1.3.3. Simple client-centric example

The server-centric approach is appealing because of its simplicity and transparency, but it has drawbacks as well. Ajax development is more effective and natural when the majority of the application is running from the browser instead of on the server. One of the main principles of an Ajax application is that the browser is supposed to be delivered a smarter application from the server, thus limiting the server’s role to providing only the data required to update the UI. This approach greatly reduces the amount of data sent back and forth between the browser and server.

To get started with the client-centric approach, let’s add a new web service called HRService.asmx. For clarity, deselect the Place Code in Separate File option in the Add New Item dialog, and then add the service.

Tip

A common best practice would be to define an interface first (contract first) and to keep the logic in a separate file from the page. However, this example keeps things simple so we can remain focused on the Ajax material.

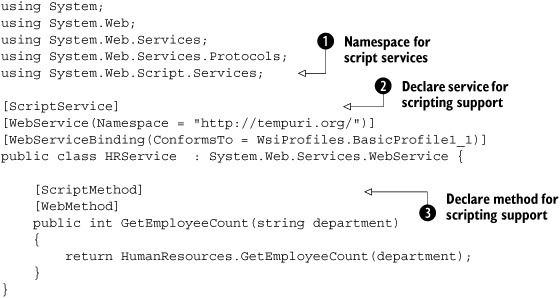

Next, paste the code from listing 1.13 into the web service implementation to add support for looking up the employee count.

Listing 1.13. Adding attributes to the class and methods

First, note the ![]() using statement for the System.Web.Script.Services namespace. This namespace is part of the core ASP.NET AJAX framework that encapsulates some of the network communication

and scripting functionality. It’s not required, but it’s included to save you a little extra typing. Next are the new attributes

adorned on the

using statement for the System.Web.Script.Services namespace. This namespace is part of the core ASP.NET AJAX framework that encapsulates some of the network communication

and scripting functionality. It’s not required, but it’s included to save you a little extra typing. Next are the new attributes

adorned on the ![]() class and

class and ![]() method declarations of the web service. These attributes are parsed by the ASP.NET AJAX framework and used to determine what

portions of the service are exposed in the JavaScript proxies. The ScriptMethod attribute isn’t required, but you can use it to manipulate some of a method’s settings.

method declarations of the web service. These attributes are parsed by the ASP.NET AJAX framework and used to determine what

portions of the service are exposed in the JavaScript proxies. The ScriptMethod attribute isn’t required, but you can use it to manipulate some of a method’s settings.

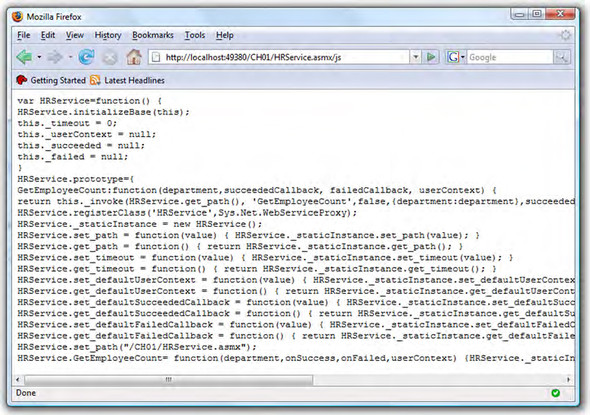

If you view the ASMX file in your browser but append /js to the end of the URL, you get a glimpse of the JavaScript proxy that is generated for this service. Figure 1.14 shows the generated JavaScript proxy that is produced by the framework after decorating the class and methods in the web service.

Figure 1.14. The framework generates a JavaScript proxy so calls to a web service can be made from the client-side script.

In chapter 5, we’ll spend more time explaining what the proxy generates. In the meantime, if you glance at the proxy, you’ll notice at the end the matching call to the service method GetEmployeeCount. This gives the client-side script a mechanism for calling the web methods in the service. The call takes a few extra parameters that you didn’t define in the service.

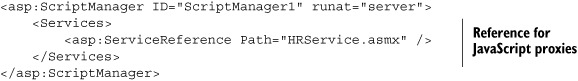

With a web service ready to go, you can create a new page for this solution. Start by adding a new web form to the site, called EmployeeLookupClient.aspx. The first requirement in adding Ajax support to the page is to include the ScriptManager control. This time, you’ll also declare a service reference to the local web service, to generate the JavaScript proxies for the service that you can now call from in the client-side script (see listing 1.14).

Listing 1.14. Adding a service reference, which will generate the JavaScript proxies

To complete the declarative portion of the solution, copy the code shown in listing 1.15.

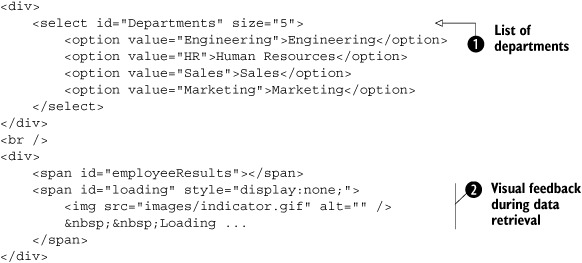

Listing 1.15. Markup portion of the client-centric solution

Because you aren’t relying on any of the business or UI logic to come from the server, you can use normal HTML elements on

the page instead of the heavier server controls. This includes a select element for the list of ![]() departments and a

departments and a ![]() span element to display visual feedback to the user when retrieving data from the server. To make this page come to life, add

the JavaScript shown in listing 1.16.

span element to display visual feedback to the user when retrieving data from the server. To make this page come to life, add

the JavaScript shown in listing 1.16.

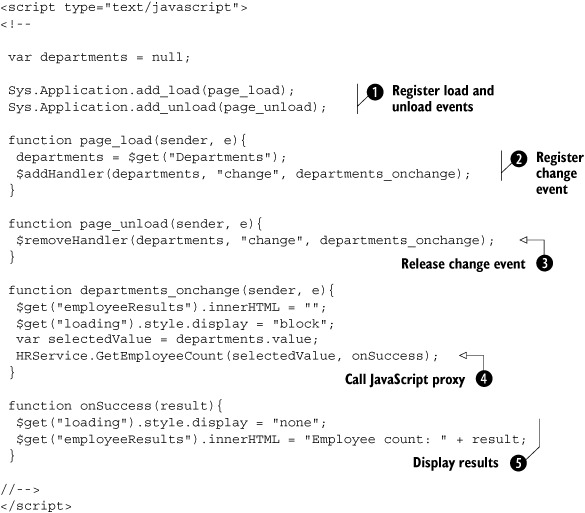

Listing 1.16. The script portion of the employee lookup application

Note the functions registered with the application model for the ![]() load and unload events in the browser. If you recall from the earlier overview of the core library, the client framework provides a page

lifecycle similar to the ASP.NET lifecycle. In this case, you use the load event as an opportunity to

load and unload events in the browser. If you recall from the earlier overview of the core library, the client framework provides a page

lifecycle similar to the ASP.NET lifecycle. In this case, you use the load event as an opportunity to ![]() register a handler for any changes to the list of departments. In addition, you use the unload event to responsibly

register a handler for any changes to the list of departments. In addition, you use the unload event to responsibly ![]() remove the registered handler.

remove the registered handler.

Here’s something new: commands that begin with $. These are shortcuts or alias commands that are eventually translated to their JavaScript equivalents. For example, $get is the same as document.getElementById. This little touch comes in handy when you’re being mindful of the size of your JavaScript files. It also provides an abstraction layer between browser differences.

This brings us to the registered handler that’s invoked each time the user selects a new department from the user interface.

When this happens, you make a ![]() call to the web service to retrieve the employee count:

call to the web service to retrieve the employee count:

HRService.GetEmployeeCount(selectedValue, onSuccess);

The first parameter in the call is the selected department in the list. The second parameter is the name of a callback function

that is called when the method returns successfully. When the call ![]() returns, the user interface is updated dynamically. Running the application produces an output similar to the previous server-centric

example.

returns, the user interface is updated dynamically. Running the application produces an output similar to the previous server-centric

example.

1.4. Summary

In this chapter, we began with an introduction to Ajax and the XMLHttpRequest control. We then moved to the ASP.NET AJAX framework and examined its architecture and goals. Keeping things at an upbeat pace, we delved into the framework with examples for both client-side and server-side development. As a result, you may have felt rushed toward the end of the chapter. Fortunately, the remaining chapters will investigate and clarify each portion of the framework in much more detail.

This chapter was intended to whet your appetite for what the framework can accomplish. You should now have a high-level understanding of how ASP.NET AJAX empowers you to quickly and more easily deliver Ajax-enabled applications.

Succeeding chapters will build on this foundation by going deeper into both the client- and server-side portions of the framework. The next chapter begins our discussion of the client-side framework by examining the Microsoft Ajax Library and how it simplifies JavaScript and Ajax development.