2

Superior Performance Comes From Alignment

“Most things of value are the by-product of an effective process. Build enjoyment into that process and make the journey itself a success.”

—Unknown

In this chapter, we want to show how having the firm’s management, systems, and people aligned is the correct and, perhaps, only way to achieve superior performance over a long period of time. You may think that finding superior performance isn’t anything more than the search for the Holy Grail, but we don’t believe so. In each market and industry, certain firms outperform the competition.

Throughout the chapter, we explore how aligning management, organizational process, and individual goals can increase overall performance. We examine different performance variables and models and then look at individual goals to make sure they are aligned with firm goals.

We often hear from managing owners that performance is only about people. Traditionally, firms placed emphasis on the individual performer. Let’s “fix” employees, so they become better performers. Let’s hire more “A” players, so we get better results.

Although an individual’s will and skill are certainly important, they do not stand alone nor do they sustain most employees or owners in the long run. We must also think about systems. Geary Rummler and Alan Brache1 observed in Improving Performance: How to Manage the White Space in the Organization Chart, “If you pit a good performer against a bad system, the system will win almost every time.” Bottom line, are you spending too much time and energy trying to fix good people and too little time fixing broken systems?

What, then, are the missing links that enable firms to achieve consistent superior performance when people are only part of the equation? Although the individual ultimately produces, the firm must be properly organized and managed and have effective systems in place. Consider the following equation:

Organization + Processes + Individual Track Record = Performance

Performance Variables

Many variables affect performance either positively or negatively. Examples that affect performance negatively include, but are certainly not limited to, owners who demotivate employees, firms without clear goals and strategies, rewards based on subjective measures, or resources that are not allocated appropriately.

To improve the performance of any organization, leaders must take a holistic look and understand how multiple variables influence performance, realizing that people represent just one of them.

In Compensation as a Strategic Asset: The New Paradigm, we noted, “No matter how noble or powerful your organizational mission (why your firm exists), that mission (and your longterm vision) cannot be achieved unless you understand the ecosystem that supports it.” To achieve your desired results, you must begin to create alignment by being clear about who you are, who you serve, and why and how you do so.

Organizational alignment requires a linking of strategy, systems, processes, and people to best accomplish the mission, vision, and desired business results of an organization. Alignment occurs when the preceding elements are mutually supportive and focused on effective and efficient delivery of results.

The first step is an understanding of why organizations get the good and not-so-good results they get, and it’s not based on their compensation criteria or methodology. According to the late Jim Stuart, FranklinCovey consultant, “All organizations are perfectly aligned to get the results they get.”

The 7S Model

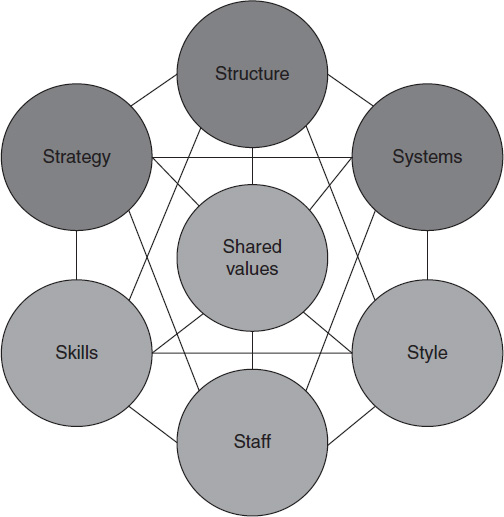

The 7S Model was developed by Tom Peters, Robert Waterman, and Julien R. Phillips, while working for McKinsey & Company, a global management consulting firm, when they first published the 7S Model in their 1980 article “Structure Is Not Organization” in Business Horizons magazine. McKinsey’s 7S Model illustrates the seven key components of an organization, which are charted in figure 2-1. The model maintains that an organization is not just its structure, but it consists of seven distinct elements, three of which are dubbed “hard” and four of which are dubbed “soft.”

The 7S Model which they developed and presented became extensively used by managers and consultants and is one of the cornerstones of organizational analysis.

The three “hard” S elements—strategy, structure, and systems—are tangible and easy to identify. They can be found in a firm’s strategy statements, business plans, organizational charts, and other documentation. The four “soft” S elements—skills, staff, shared values, and style—are intangible. They are difficult to describe because capabilities, values, and elements of your firm’s culture are continuously developing and changing. The “soft” elements are highly determined by the people who work in the organization. Therefore, planning or influencing the characteristics of the “soft” elements is much more difficult. Although the “soft” factors are intangible, they have a significant impact on the “hard” strategy, structure, and systems of the organization.

(Reprinted from Business Horizons, Volume 21, Issue 3, Robert Waterman, Thomas Peters and Julien Phillips, “Structure is Not Organization,” pp. 14-26, June 1980. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier.)

Table 2-1 from In Search of Excellence: Lessons from America’s Best Run Companies, illustrates Peters’s, Waterman’s, and Phillips’ description of the seven Ss.

| The Hard Ss | |

| Strategy | Actions an organization takes in light of changes in its external environment |

| Structure | Basis for specialization and coordination influenced primarily by strategy and by organization size and diversity |

| Systems | Formal and informal procedures that support the strategy and structure |

| The Soft Ss | |

| Style and culture | The culture of the organization, consisting of two components: Organizational culture: The dominant values, beliefs, and norms that develop over time and become relatively enduring features of organizational life Management style: more a matter of what managers do than what they say; how they spend their time |

| Staff | The people and human resource management processes used to develop managers, shape basic values of management cadre, introduce recruits to the company, manage the careers of employees |

| Skills | The distinctive competencies—what the firm does best and what individuals do best |

| Shared values | Guiding concepts, fundamental ideas around which a business is built |

(Tom Peters, Robert Waterman, and Julien R. Phillips, In Search of Excellence: Lessons from Americas Best Run Companies (New York: Warner Books, 18=982), p. 9-11.)

Table 2-2: Balancing the Seven Ss

| The Hard Ss | |

| Strategy | Actions a firm takes in light of regulatory, technological, economic, or social changes that effect the accounting profession, the firm, or the firm’s clients |

| Structure | The way the firm is organized (for example, departments, niches, service groups, work teams, and so on) and the way work flows through the firm |

| Systems | Formal and informal processes and procedures that support the strategy and structure |

| The Soft Ss | |

| Style and culture | The culture of the firm consisting of two components:

|

| Staff | The people and human resource management processes:

|

| Skills | The distinctive competencies of the firm and of each individual within the firm |

| Shared values | Guiding concepts, fundamental ideas around which the firm is built—how individuals within the firm treat each other and how they treat clients and other key stakeholders |

As in nature, organizations have an ecosystem in which each element has its place yet is dependent on the other elements for long-term survival. When you change one element in the ecosystem, you affect the others, whether planned or not. Effective organizations generally struggle to maintain a fine balance between and among the seven Ss. Table 2-2 illustrates how this could work in an accounting firm.

If one of the seven elements is changed, each of the other elements is affected. For example, a change in human resource systems, like internal career plans and management training, will have an impact on organizational culture (management style) and, thus, will affect structures; processes; and, finally, characteristic competencies of the organization.

According to Dagmar Recklies,2 when firms try to make changes, they usually focus their efforts on the “hard” Ss of strategy, structure, and systems, believing these are easier to change. “If we change our strategy,” says one managing owner, “won’t we get different results?” Traditionally, public accounting firms have taken this approach when starting a change process. Unfortunately, however, it is the wrong place to start.

Most companies and public accounting firms care less for the “soft” Ss of skills, staff, style, and shared values. In In Search of Excellence, Peters and Waterman observed that most successful companies work hard at these “soft” Ss. Few organizations, including public accounting firms, have taken their advice to heart. Because structures and strategies are difficult to build or refine when the organization’s culture is dysfunctional, or values are not shared, “soft” factors can make or break a change process. The dissatisfying results of most corporate mergers, whether small or spectacular megamergers, are often based on a clash of completely different cultures, values, and styles, making it difficult to establish effective, common systems and structures.

Other Models

Although we believe the 7S Model still is useful in analyzing and aligning a firm today, other models can also help firms sharpen their focus on ultimate performance.

The Nine Performance Variables

In Rummler’s and Brache’s Improving Performance: How to Manage the White Space in the Organization Chart, the authors discuss three levels of performance and three performance needs for any organization, as presented in table 2-3.

Table 2-3: The Nine Performance Variables

| The Three Performance Needs | ||||

| Goals | Design | Management | ||

| The Three Levels of Performance | Organization Level | Organization Goals | Organization Design | Organization Management |

| Process Level | Process Goals | Process Design | Process Management | |

| Performer Level | Performer Goals | Job Design | Performer Management | |

(© 1990. Improving Performance: How to Manage the White Space on the Organization Chart by Geary A. Rummler and Alan P. Brache. Reprinted with Permission.)

To maximize performance, each of the nine performance variables needs work. You must examine the entire firm, not just specific systems, departments, or areas. For example, having great job descriptions but lacking performance goals or performance management mechanisms will likely not set the firm up for superior performance. Although this full examination may appear to be an overwhelming task, it must be started and completed in firms that want to improve performance. The best place to start is at the organizational level.

Organization Level

Organization Goals → Organization Design → Organization Management

Organization Goals

We find that most professional services firm partners cannot articulate the firm’s high-level goals. In fact, a recent study by FranklinCovey and Harris Polling found that only 15 percent of workers know their organization’s most important goals, and 19 percent of those polled indicated they are passionate about their organization’s goals.

A line from Alice in Wonderland captures the place at which most firms tend to be when it comes to organizational goal setting: “If you don’t know where you are going, any road will get you there.”

Are we on our path to the future by design or default? In today’s environment of stiff competition, constantly changing technology, complex regulations, globalization, and fee pressure, it’s difficult to understand why firms do not put more value in setting clear direction and articulating that direction throughout the organization.

Partners in leadership positions who are serious about improving performance need to learn how to

clarify the mission (why the firm exists).

create the vision (or firm’s aspiration).

set high-level objectives.

create strategies.

Leaders cannot just ask their partners to make it happen; they must provide them with a framework and direction.

Organization Design

Firm leaders tend to look at their organizations vertically via the organizational chart. Organizational design is not just developing an organizational structure that can be depicted in an organizational chart (a picture of the organization from a vertical perspective with leadership at the top and showing what is commonly called the chain of command). An organizational chart is internally focused rather than client focused and does nothing to help the firm improve its performance.

If we think from a horizontal perspective, however, we recognize it’s not about the chain of command within the organization but how work enters and flows through the organization, so deliverables and results flow back to the client. To achieve a higher degree of performance, firms need to

understand how internal systems do or don’t work together.

identify where internal systems break down.

ensure functional areas (tax, consulting, accounting, and so on) are connected or aligned to produce and deliver effectively and efficiently.

Organization Management

Having goals and a well-structured organization does not guarantee success. At the organization management level, the question you need to ask yourself and your team is, “Does our executive team manage goals, performance, resources, and interfaces?” For accounting firms, this means the managing owner, management team, or executive committee, as well as department heads or niche or functional leaders, need to

determine clear and motivating short- and long-term goals for the firm, department, or function that support overall organization goals.

organize the firm around client needs and obtain regular client feedback about the firm’s performance, taking corrective action if performance is faltering.

manage internal conflicts and firm politics.

manage resources (people, technology, and dollars) efficiently.

clarify performance expectations

identify, assign, and empower leaders who can implement the plan rather than tolerate ineffective owners in key roles.3

Good management alone does not ensure high performance. Imagine a firm with a great management team and motivated people but inefficient decision-making, communication, and work processes. Work takes more time and write-downs are often high, causing clients to become dissatisfied and employees to lose their spirit. The end result is low performance.

Process Level

Process Goals → Process Design → Process Management

Every organization, including accounting firms, has some sort of input and then one or more outputs. A process is what takes place between the two. Although most firms focus on the output (result or deliverable), they don’t pay enough attention to the process itself: that series of steps designed to produce the service (audit report, tax return, consulting report, and so on). In the end, an organization can only be as effective as its processes because its processes drive individual and collective behavior.

So, firm leaders must take a good look inside their organizations to evaluate how well their processes work. What keeps small firms from growing is a lack of clearly defined processes, often not written and only residing in the heads of partners. As a result, everyone is using their own (and different) process for client acceptance, billing, working paper preparation, and so on. Let’s look at the example in table 2-4 in which we compare two hypothetical firms of similar size in the same geographic location.

Firm A simply has better processes than firm B, and as a result, internal and external work gets done more efficiently and profitably, as well as with higher quality, than in firm B.

| Firm A | Firm B |

| Formal strategic planning. | Silo planning. |

| Quarterly revenue forecasting. | Annual budget. |

| Uniform way to create a client work file. | Each partner creates client work files differently. |

| Defined billing and collection policy. | Partner bills and collects according to his or her own whims. |

| Formalized recruiting process. | Informal recruiting process. |

| Formalized employee training program. | “Sink or swim” culture. |

| Client service linked to client needs. | Client service linked to owner needs. |

Process Goals

Process goals, when achieved, can support one or more of the firm’s organization goals. Most firm leaders don’t think about process goals, and when they do, these goals are often either immeasurable or hard to measure. Process goals should always be directed toward the needs of the clients, whether internal or external. Hence, you can separate your process goals into the two general categories illustrated in table 2-5.

Table 2-5: Process Goal Categories

| Internal Client Goals (Shareholders and employees) | External Client Goals (Clients, referral sources, vendors, and so on) |

| Strategic planning | Marketing |

| Budgeting | Sales management |

| Talent management (including recruitment, selection, training and development, performance management, and compensation and benefits) | Client service and relationship |

| Management information systems | Referral networking |

For example, let’s look at the typical billing and collection process. Too often, we might see a goal such as “Improve the collection process.” Very vague! How could we change this goal so that it’s measurable? Perhaps we could say, “Reduce the average amount of time between invoice issuance and invoice collection from 46 days to 36 days by December 31.” In this case, the goal is both specific and measurable and has a deadline. This goal would support an overarching organizational goal to improve cash flow, so the firm can reduce draws on the line of credit and, thus, lessen annual interest charges. Now, there is a clear link between a goal to improve the billing process goal and a larger firm goal.

Process Design

We set organizational goals and, in some cases, departmental goals first and then ensure processes are designed to meet those goals in an efficient manner. We encourage you to examine major processes to determine if they are logical (that is, drive the behaviors and results you intend). Do the steps in the process add value to the output and do it in an efficient way? In an accounting firm, you can test to determine if a process is efficient by the number of times work starts and stops. An easy example is the tax return process. Ideally, the return should not start until all information is obtained from the client. In many firms, the return is started, and subsequently, the preparer stops to return to the client for more information. Firm leaders would be wise to require all information to be available upfront and use paraprofessionals or administrative professionals to gather it. The tax preparer could then do what he or she does best: prepare the return.

Another example is delivering client audit reports and corporate tax returns. Firms are often consistently late in delivering these items to clients. Possible reasons include a lack of an integrated delivery process, territorial bickering between the tax and audit departments, or no clear responsibility for timely delivery. These types of examples clearly indicate the lack of a customer support process.

A final example near and dear to many managing partners’ hearts is the new client acceptance process. Common disconnects in this basic process include the

owner does not complete (or partially completes) the new client acceptance form.

owner starts work without approval or before a client background check is done.

data entry team enters new clients infrequently.

client information must be added to multiple, noninterfacing systems.

system allows charge time to be accumulated prior to client setup and client number.

The lack of a well-defined client acceptance process negatively impacts business development, administrative, financial, and production areas because these team members are forced to go back to complete or redo steps in the process, thus causing inefficiencies.

Process Management

Common sense suggests a process will not be consistently used or followed unless it is fully automated, which could be the case in a sophisticated time and billing system. For the most part, however, key processes (client service, administrative, leadership, and so on) in an accounting firm need to be managed. Because you cannot attack every process in the firm simultaneously, just start with those that cause team members and the firm the most headaches and that negatively influence your competitive advantage. For example, your flowthrough process (the time it takes for work to enter and leave your firm) could be hurting realization and, ultimately, profitability and client retention. Perhaps your employee growth and learning process may not be developing employees fast enough or in the right areas. Again, you probably already know the key processes you need to address. Simply rank them by their impact on the firm’s competitive advantage.

In the same fashion that organizational goals need to be filtered through the firm, process goals need to be broken down into subgoals at critical process steps. Let’s use our client acceptance process previously described. To manage the process more easily, you often need to create key subgoals. A process goal may be decreasing work in progress. A subgoal may be increasing the percentage of client acceptance forms that are complete and accurate when turned in.

Let’s consider our client management information process. In our previous example, the firm has multiple client information systems that do not interface. The firm goal may be reducing operational costs. A subgoal would be to reduce the number of client information systems, thus involving a vendor or internal technology department.

One final comment about process management: you should assign responsibility to one individual for improving the process, even though he or she may lead a team in making the improvements. We’ve heard the old saying, “If everyone is responsible, then everyone believes everyone else is doing something about it. Ultimately, no one is doing anything about it.” After assigning responsibility, goal accomplishment should be tied into the individual’s performance bonus.

Performer Level

Job and Performer Goals → Job Design → Performer Management

We arrive now to a microview of the firm at the performer level. As shared earlier, we tend to blame people for not getting planned results rather than looking at how the firm’s processes or management of people drove the behaviors that led to poor results.

Too often, we hear managing owners and department and niche leaders explain how they manage. We’re sad to report it generally goes like this:

First, we train them to do things our way.

Then, we coach them if they don’t perform.

If that doesn’t work, we threaten them.

Then, we discipline them by reducing compensation (for owners) or awarding minimum or no raises. We also give them less challenging engagements.

Finally, we terminate them and look for their replacements.

This, we are afraid, represents the vicious blame game.

This near-sighted view of the problem ignores the firm’s ecosystem. Do managing owners really believe people are the problem and that nothing in the organization needs analysis and change? How do you explain the fact that an “A player,” whether owner or employee, is terminated for lack of performance only to become a superstar at another firm? Our experience suggests the individual didn’t change much, if at all. What changed was his or her environment.

Individual Performer Goals

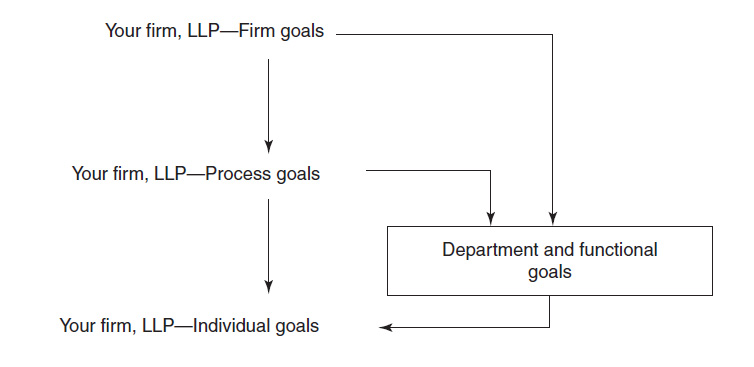

We have known for a long time that goals at the individual level should support firm and process goals. Figure 2-2 portrays goal alignment for any organization, regardless of whether it’s a CPA firm.

To achieve superior performance, individual goals must support functional goals and, ultimately, firm goals. Process goals that support a department or the entire firm, when achieved, make accomplishment of individual goals much easier.

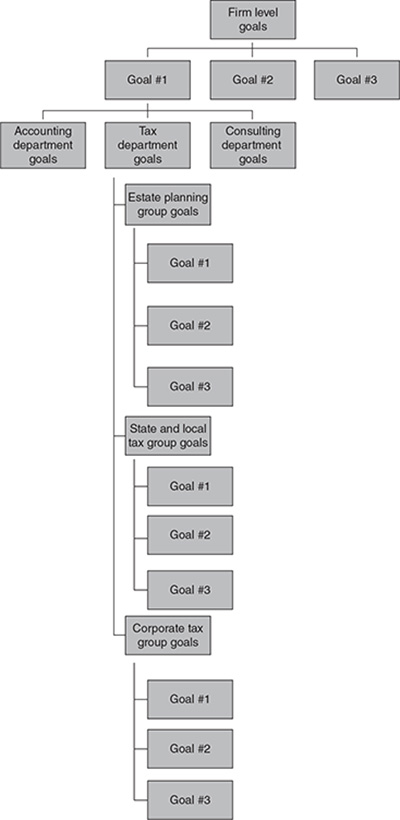

“Line-of-Sight” or Cascading Goals

An individual’s performance goals should be based on, or closely aligned to, the goals of those above him or her in the firm. For example, a manager’s goals should support the goals of one or more owner’s goals. The owner’s goals should support the goals of the department in which he or she works, which, in turn, should support the goals of the firm.

(© 1990. Adapted from “Improving Performance: How to Manage the White Space on the Organization Chart” by Geary A. Rummler and Alan P. Brache. Reprinted with Permission.)

To help employees increase “line of sight,” you may want to flowchart how their activities support the goals of their superiors and how their superiors’ goals support the goals above them. Cascading goals for a typical accounting firm are illustrated in figure 2-3.

When a firm sets a new goal or creates a new process, needed changes at the individual performer level must also be addressed because people work more effectively and produce better results when processes motivate them to do so. We must nonetheless be aware that people develop, refine, and work within the process. Performance in a professional services firm comes down to people, and their long-term performance will be better when they have good supporting processes. At the performer level, we look at the jobs to be done and the people who perform those jobs and then set goals accordingly.

Job Design

Jobs should be designed so they maximize the job performer’s ability to support the processes. Job descriptions often contain many responsibilities. For example, if you look at the job description for a typical CPA firm manager, you may find the following responsibilities:

Takes a leadership role in the development and implementation of firmwide marketing initiatives.

Actively seeks opportunities for introducing additional services to existing clients.

Develops and nurtures prospective client relationships by introducing other principals, directors, managers, and so on into the relationship.

Maintains (and helps team members develop) personal business and community contacts.

Nurtures and expands referral sources (clients and nonclients); helps others do so, as well.

Demonstrates ability to develop and nurture prospective client relationships that result in secured engagements.

Ensures secured engagements meet client acceptance and retention qualifications and are priced according to potential risk.

Develops (or codevelops) and implements a personal practice development plan.

Manages client retention or acceptance and monitors risk reward.

Develops and maintains strong working relationships with client contact(s) (for example, owners, leaders, or managers, as well as attorneys, bankers, and so on).

Initiates new engagements and empowers others to lead or teach others to plan, implement, and review the engagements.

Works with team members to ensure that client expectations are being set and managed appropriately (and exceeded if at all possible).

Attends client meetings; presents at executive or board meetings as required.

Identifies business issues (from a global and client perspective) and develops creative solutions to complex client issues.

Reviews and approves engagement budgets.

Ensures that client service agreements are executed.

Monitors or reviews actual time charges on engagements in an effort to improve realization or contribution margin on engagements.

Ensures all engagement reports are prepared and reviewed.

Reviews and approves client billings, as appropriate.

Evaluates client profitability to ensure compliance with firm standards.

Takes responsibility for team- and firmwide profitability.

Engages exceptional preparation or reviews skills in unique or special circumstances.

Demonstrates exceptional knowledge of selected specialty areas.

Demonstrates exceptional analytical and problem-solving skills.

Stays current on relevant and emerging specialty issues, industry issues, market issues, and accounting issues.

Prepares and reviews complex correspondence, reports, recommendations, proposals, and so on, on behalf of the firm.

A complete list of job competencies and responsibilities is important because that’s what we expect from day to day. When goals are established, however, we should help performers understand which of these competencies and responsibilities will need to be developed and utilized most to achieve their goals, and the firm should provide the resources to help them do so.

Performer Management

In Improving Performance: How to Manage the White Space in the Organization Chart, Rummler and Brache define performer management as managing the human performance system. They explain this to mean that people, for the most part, are motivated and talented. Are we generally in the practice of hiring unmotivated or untalented people? We don’t think so. If people don’t perform at a high level, the cause is likely in the system in which they have been asked to perform. We will discuss this later, but for now, here are some questions to think about:

Do performers have the necessary competencies to adequately perform at their given level?

Do they know what is expected of them?

Do they have clearly stated performance standards?

Are they rewarded for achieving these expectations?

Do they receive relevant and timely information about their performance?

Do they know whether they are meeting their goals?

Are they giving their best every day, or do they seem burned out?

Final Thoughts

Goal alignment is critical to organizational success, and firms generally need to devote more time than they do to ensuring this alignment is present If you say you can’t because you don’t have time, then don’t read this book. Coral’s dad always says, “Can’t means won’t … unwilling to try.” We say it means you either are not interested in superior performance or believe proper alignment will not get you there.

We also encourage you not to get overwhelmed by what you read here. What we recommend does not happen in 1 or 2 years. We simply suggest you begin the journey. The Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu wrote more than 2,500 years ago, “A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.”

In chapter 3, we discuss another element critical to building a high-performing firm: vision. In it, we discuss creating a compelling vision that gets owners and employees excited and motivated about what the firm is trying to build and how this process leads to performance.