6

Why You Need to Reward Different People Differently

“All of us perform better and more willingly when we know why we’re doing what we have been told or asked to do.”

—Zig Ziglar

Nearly all firms that ask us to work with them are dissatisfied with the firm’s current owner compensation system. The trigger is often a change in leadership, which is a good time to review a variety of systems. Another trigger is the belief by younger owners that the system is unfair. Whatever their reasons, firm leaders want compensation to be more transparent, more performance based, fairer, and more effective.

To create or re-design an effective compensation plan, you must consider many things. In this chapter, we look at seven reasons why we need to reward people differently today. There may be more, but we hear about these most often:

Performance-compensation gap

The need to reward performers

Align monetary and nonmonetary rewards with position level

Evolving business models

Competitive landscape

Work-life balance

Generational differences

We also share more results from our 2011–12 Performance Management and Compensation Survey.

We saw in chapter 1, “Workforce Trends in the Twenty-First Century,” the many trends affecting the ways employees carry out their work. Just 15 years ago, for example, coworkers believed you weren’t working if you weren’t at your desk. That perception has certainly changed. Technology allows people to work remotely and at any hour of the day or night. In the same fashion, firms are rethinking their reward systems. In our first book, Compensation as a Strategic Asset: The New Paradigm, we noted that although the majority of firms still had a formula method to determine compensation, they said they would switch to a pay-for-performance system. This trend is not only continuing, but the performance reward is now linked more closely to business strategy and outcomes.

Throughout part 3 of this book, we explain how to reward performance, regardless of your firm size. Some believe pay-for-performance systems work best for sales professionals or strong business developers. We find, however, that a pay-for-performance system, if tied to firm goals and strategies and well-written, can work for everyone at all levels in the firm.

We discussed the importance of goal alignment in previous chapters, and now, we make the case that a pay-for-performance bonus system is the final missing piece of the puzzle. Without one, it is difficult to link the firm’s goals and an individual’s performance. Employees who understand how their day-to-day work performance drives overall business goals and how their compensation and other rewards are tied to their performance are generally more motivated and engaged.

We find that clients are wonderful sources of information and inspiration, and the following sections detailing the reasons for moving to a pay-for-performance system were shared with us by clients who have already embraced, or are moving toward, a pay-for-performance system. We’ve organized these reasons under three major categories: financial, operational, and generational.

Financial Reasons

Performance-Compensation Gap

For as long as we know, performance-compensation gaps have existed in firms. Firm founders usually paid themselves more than they paid others. Either the managing partner decided compensation, or it was based on an equity or a seniority system. Today, firms are moving from such cultures of entitlement to cultures of performance. Under these conditions, the performance-compensation gap becomes more apparent. There is no place for people to hide in the new environment.

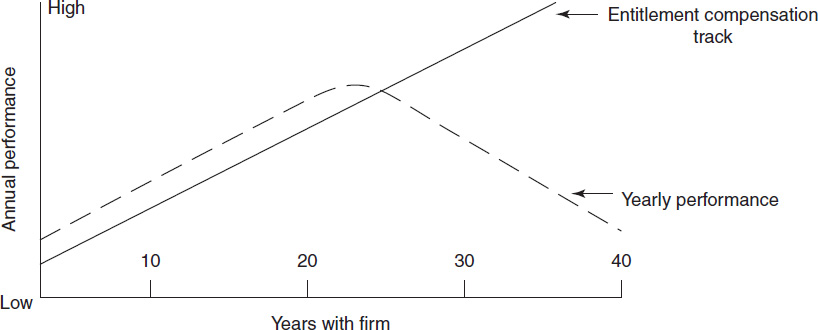

When firms move toward the performance end of the entitlement-performance continuum, senior owners often push back. Figure 6-1 shows what happens to most owners and long-term employees over time. Firms have known that younger employees often have great energy and drive and, as a result, can produce at high rates. Senior employees should have greater skills, referral sources, and client relationships. In the new environment, younger professionals often move ahead faster financially than they would have in the old entitlement system in which young employees and junior owners would not have seen their compensation increase accordingly, especially if the culture was “wait your turn for the golden ring.”

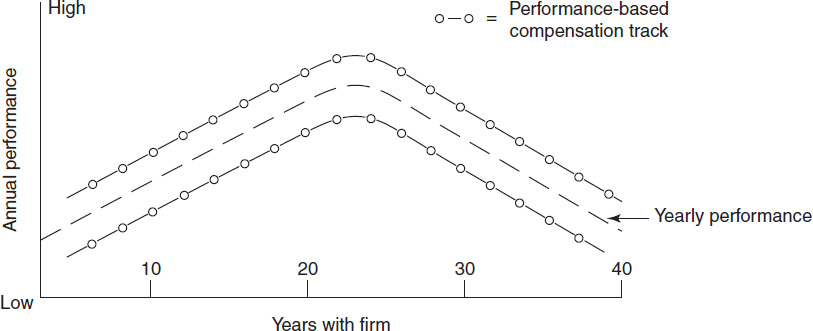

Today’s younger workers, often referred to as Millennials, generally do not want to wait; they find it difficult to wrap their heads around a lockstep or equity method of compensation. They see the chart illustrated in figure 6-1 in their mind’s eye: the gap between performance and compensation. Such a gap can cause conflict and dysfunction, in addition to underperformance. A pay-for-performance program helps close the gap because one’s compensation is based on his or her contributions to the firm, not seniority or equity. See figure 6-2 for an illustration.

Figure 6-1: The Entitlement Performance-Compensation Gap

Figure 6-2: The Performance-Based Compensation Gap

Need to Reward the Performers

The second financial reason deals with rewarding those who actually earn the rewards. In any firm, you will find a typical distribution of people: some high performers, a lot of good performers, a number of mediocre performers and some underperformers. The traditional compensation systems tended to reward everyone equally. The primary reason for developing a new compensation system or changing your current system should be to reward performance. We are seeing this take place in many firms, regardless of their size.

Not too long ago (2009), the law firm of Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr LLP announced a new compensation system designed to break away from the lockstep method1 and shift a larger chunk of lawyers’ pay from their base salary to their bonus.

The new system, unveiled today after two years of planning, will be phased in through 2012, according to William Lee, the firm’s co-managing partner, and Carol Clayton, the firm’s assistant managing partner. The crux of the change involves dividing nonpartners into several tiers and linking each of those tiers to a set base salary, Lee and Clayton say. Within those tiers, pay will vary greatly depending on individual bonuses. Those bonuses will be merit-based and will not be linked to seniority or billable hours. The goal is to pay top performers in each tier more than they would make under Wilmer’s current lockstep system, Lee says ….

But one thing is for sure, the firm says: That base salary will comprise a smaller chunk of a lawyer’s total compensation under the new system. The internal memo puts it this way: “A larger percentage of each lawyer’s total compensation will be built into the annual performance bonus,” the memo says. “This system obviously will result in greater differentiation in compensation, allowing our strongest performers to earn more than they could at peer firms that, like WilmerHale, peg their compensation at or near the top of the market.”2

Another reason to reward the performer is the ongoing talent shortage. When Charles Dickens wrote, “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times,” he could have been referring to challenges with talent management in the twenty-first century. What firm today couldn’t use more talented and experienced team members? Senior tax professionals, who are worth their weight in gold, could be traded as in an NFL draft. Even though enrollment in undergraduate accounting programs has increased, it will be a few years before those who stay the course enter the job market. Jerry Love, chairman-elect of the Texas Society of Certified Public Accountants, captured the current environment when he said in a March 2006 article in the Austin Business Journal, “The common theme is, ‘I need more people, and I need more experienced people.’ Pretty much the answer is you are just going to have to wait a few years. Right now we are just trading people.”

Align Monetary and Nonmonetary Rewards With Position Level

The third financial reason relates to aligning rewards to the specific position level. We created table 6-1 to show the potential importance of various types of rewards for different levels in a professional services firm. What may be important to a nonequity or an equity owner could be very different than what is important to an entry-level or a four-to-seven-year person. Entrylevel employees tend to focus more on base compensation, opportunity to grow, and flex time. Owners, however, tend to focus more on issues related to retirement income, equity, and so on.

When it comes to bonuses, firm owners are beginning to realize how important it is to put a larger percentage of compensation at risk as an individual progresses from staff accountant, to supervisor, to manager, and so on. Table 6-1, although not scientific, shows how different rewards and benefits can be more important to professionals at different times during their careers. For example, because most owners are handsomely paid, base compensation may not be as important to them as it is to a new professional whose base salary is the majority of his or her total compensation. The same may be said for flex time. Owners, for the most part, have the ability to come and go as needed. Younger professionals, who are often not given the same freedoms as owners, may value flex time more.

Table 6-1: Align Monetary and Nonmonetary Rewards With Position Level Matrix

| Reward | Entry Level | 2–3 Years | 4–7 Years | Over 8 Years | Director | Owner |

| Base Comp | A | A | A | A | B/C | B |

| Bonus | A/B | A/B | A/B | A/B | A | A |

| Flex Time | A/B | A/B | A/B | B | C | C |

| Development Benefits (for example, MST, CVA) | D | C | A/B | A/B | C/D | C/D |

| Deferred Compensation | D | D | D | B | A | A |

| Equity | D | D | C | B | A | A |

| Mentoring | A | A | A | A/B | B | B/C |

| Recognition | A | A | A | A | A | A/B |

A = very important, B = important, C = somewhat important, and D = not important. (Copyright 2012 August Aquila. All Rights Reserved. Used with permission.)

The purpose of table 6-1 is not to prove the value of each benefit but to make the case that rewards and benefits can be more meaningful to certain levels or people than others. When considering reward additions, changes, or deletions, it’s respectful to check first with the people who will or may get them.

Operational Reasons

Evolving Business Models

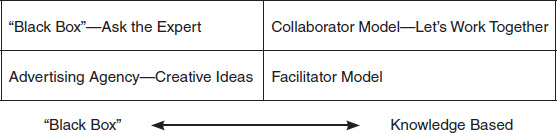

The world in which professionals work today is vastly different from the traditional work environment during the first 90 years of the twentieth century. Accounting firms have employed a number of business models over the years. In each of these models, the service provider remains the expert. Recently, however, this model has evolved so that the wise service provider collaborates with the client to design solutions. A brief history of the service provider and client relationship, described in the following sections, sheds light on this. The four professional services delivery models are illustrated in figure 6-3:

Figure 6-3: Four Professional Services Delivery Models

The “Black Box” Model—Ask the Expert

Historically, the humble client asks the expert accountant or tax adviser for answers and sage advice. The professional has specialized knowledge in a specific area (tax, accounting, consulting, wealth management, and so on) and delivers his or her advice as a “black box” service. This model assumes the individual (and, more recently, a software program) is considered to be the “black box” and has the answers himself or herself.

Client Provides Raw Data to Service Provider → Raw Data Converted Into Information → Answer Given to Client

With the advent of inexpensive tax, bookkeeping, and other software packages now available to the consumer, we find this model becoming obsolete.

The Traditional Advertising Agency Model—Here are Our Creative Ideas

Madison Avenue, the home of America’s advertising industry, also developed a “black box” method in serving the country’s largest companies. Account executives would develop a series of great and not-so-great advertising ideas and then deliver them to the client. The interaction between client and service provider was richer than in the pure “black box” method. Yet, the real wisdom, knowledge, and brilliant ideas still rested with the professional rather than the client.

Service Provider Interviews Clients → Input Converted Into Output (Creative Ads) → Service Provider Presents Ads to Client for Selection

Facilitator Model—This Is What the Outcome Might Look Like

As clients become more sophisticated and professionals specialized, more accountants have been facilitating outcomes with their clients rather than announcing them. We find one of the fastest growing business models is that of assisting clients in exploring and determining final answers for themselves rather than dictating them.

This model requires a professional with deep knowledge of the issues at hand, as well as the talent to work with the client to develop solutions.

Service Provider Facilitates Session With the Client → Service Provider Brings Specialized Knowledge to the Process → Service Provider Suggests Outcomes to the Client

Collaborator Model—Working in a True Partnership

The collaborator model is a further development of the facilitator model. In this model, the service provider and client are in an equal partnership. The professional service provider brings to the table his or her deep content expertise using a knowledge-based approach to create solutions with the clients, not for the clients. When CPAs and professional services providers show evidence they are business consultants, many of them are operating in the facilitator or collaborator model.

Service Provider Collaborates With the Client → Service Provider Brings Content Expertise → Client and Service Provider Jointly Develop Solutions

Rapidly Changing Competitive Landscape

Mergers and Demergers

The competitive landscape is in a state of constant change. Mergers of large regional firms have become the strategy of the day. Nearly half the top 100 firms completed a merger in 2012, and it looks as if that trend will continue into the future. Although many of these mergers have held together, there has been a rash of major mergers that never even made it to the altar. Recent megamergers that were announced and completed include (1) Larson-Allen-Clifton Gunderson; (2) Wilson, Price, Barranco, Blankenship & Billingsley; Warren, Averett, Kimbrough & Marino; and O’Sullivan Creel; and (3) McGladrey and Caturano & Company. There have been some megamergers that were announced but then were terminated, including Eide Bailly and Wipfli and Burr Pilger Mayer and Windes & McClaughry.

Many reasons for these mergers exist (even when they are not completed), but the major reason is to gain a larger footprint in their markets, so they can more readily compete. For this strategy to be successful, we believe firms will retain their high performers by rewarding them more than nonperformers, so they don’t risk losing them to competitors.

Generational Reasons

Our last major category deals with generational issues. Each generation grows up having major experiences define them: World War II, Korean War, Vietnam, Woodstock, the Great Recession, 9/11 terrorist attacks, and so on. We have identified two major generational reasons that are causing firms to consider a pay-for-performance plan: work-life balance and generational differences.

Work-Life Balance

The Baby Boomer generation often placed work over family, and for the last 40 years, this was the work paradigm in the accounting profession. Today, however, that model is rapidly fading. Market dynamics—parents with young children, single parents, adult children caring for aging parents, and so on—are forcing CPA firms to address the issue of work-life balance. This issue already has been addressed by Fortune 500 companies.

Major organizations, such as Chevron and Halliburton, today are offering competitive salaries plus incentives when their respective companies meet established goals. Benefits programs are becoming more flexible and are designed to help employees get the most out of work and life.

In this environment, CPA firms cannot be far behind. We have already seen both men and women in public accounting firms taking advantage of alternative career paths offered by their firms, including flex-time, part-time, and shared positions. A few firms offer part-time ownership positions to employees they want to retain.

The need for work-life balance, along with the overall shortage of qualified staff, has caused more firms to abandon their “up or out policy.” According to the AICPA work-life study A Decade of Changes in the Accounting Profession: Workforce Trends and Human Capital Practices, 38 percent of firms surveyed offered some kind of alternative career path that did not lead to an owner position. Firms will look for creative ways to keep good performers either by creating new positions within the firm or offering them compensation rewards that are based on performance, not necessarily time.

Generational Differences

According to Rick Telberg, publisher of CPA Trendlines, a research, analysis, and strategic services blog

It’s well established that there are distinctly different personal preferences and work habits among the four generations in the workplace.

For instance, as reported in “What Your Workforce Really Wants,” the generations fall in a few basic categories: the so-called Mature generation, born before 1946; Baby Boomers, born between 1946 and 1964; Generation X, born between 1965 and 1980; and Generation Y, born after 1980.3

According to Telberg, “A survey conducted by the Families and Work Institute has found that 22 percent of Boomers are ‘work-centric,’ compared to 12 to 13 percent of other generations. Meanwhile, 52 percent of Gen-X are family-centric, compared to 41 percent of Boomers.”4

The survey also found that “Gen-X fathers (those 23 to 37 years old) are spending 50 percent more time with their children than Boomers did in their younger days. Likewise, Gen-X, especially the women, are more likely to turn down career opportunities if the added responsibilities mean less time for family”5

According to Leslie Murphy, former AICPA Chair, “In the next 15 years, 75 percent of current AICPA members will be reaching or approaching retirement age.” The accounting profession’s future will be controlled by the tail end of the Baby Boomers, those born after 1960, and Generation X. With four generations currently in the ranks of firms, generational conflicts will inevitably arise as the older generations try to hold onto what they have achieved, and the newer generations strive to build for the future.

Today’s Compensation Plan

Given all of the preceding, we maintain that a paradigm shift is currently taking place in the area of firm compensation systems. Some firms will see it and embrace it, others will see it and laugh at it, and still others will not see it until it may be too late. Paradigm shifts do not happen overnight; they evolve as we receive new information or more complete information, and either way, this takes time—a transition period. However, those firms that see the shift early and embrace it can gain a competitive edge over those that laugh or do not see it until it is too late.

Living through a paradigm shift, regardless of whether you see it, generally results in change—either small or large—and some pain. To give you an idea of what firms are going through today, we share the statement of a managing owner of one of our client firms after his firm made changes to its owner compensation system: “I will say this—change is chaotic, painful, unsettling, and hard.” Need we say more?

Accounting and other professional services firms are affected by the same external economic forces as most other businesses. Human resource cost is the number one expense in most firms. During the recession of 2009–12, it became crystal clear that firms needed to control labor costs and reduce the number of nonproductive owners while, at the same time, increasing productivity and providing a higher level of client service.

Many firms have addressed these issues, but few firms have yet to fully address the most important component of this issue: their compensation plans. We know that changing a compensation system is a herculean task. Employees and especially owners may disagree over some or all elements of a new system. You will often hear us say it is difficult, if not impossible, for a firm to achieve changes in behavior if its new compensation plan has not been properly communicated, if the owners and employees lack trust in the plan, and if the new plan does not reinforce the direction set by firm leadership.

Written Win-Win Agreements

In our 2006 Owner Compensation Survey, we asked the question, “Do owners in your firm have written goals?” Eighty percent responded “No.” In our more recent 2011–12 survey, Reward & Compensation & Incentives: Pay-for-Performance, 68 percent responded “No.” Unfortunately, we don’t know how many of the same firms participated in both surveys.

If a goal is not written down, how can owners be held accountable for achieving it or be rewarded? In our 2006 Owner Compensation Survey, 74 percent of the firms responding to our survey indicated they had either no evaluation or only an informal evaluation for owners. Only 10 percent of respondents said they use a formal evaluation method. In our most recent survey, we asked “How would you describe the way in which OWNER performance is currently evaluated?

We are confident the responses will be unsurprising to you:

Formal, written annual evaluation of performance—14.0 percent

Informal, verbal (little written) evaluation of performance—36.4 percent

Combination of formal and informal—18.7 percent

No current evaluation of owner performance—30.8 percent

How can firm leaders expect better performance when only 14 percent are conducting formal, written evaluations of their owners? We believe that simply implementing formal reviews would help firms achieve a higher degree of performance and profitability.

Under the new performance bonus compensation model, goals are clearly developed and documented at the beginning of the year, and there is mutual agreement between the owner and firm management about the reward. Although management may suggest goals to owners, individual owners must take responsibility for them, and this requires commitment and buyin. This is often called a win-win agreement because owners and employees are generally focusing on goals that allow them to focus on their talents, passion, and activities (a win for them) that drive both short-term and long-term growth and profitability (a win for the firm).

The win-win agreement allows this to happen. Unless owners are involved in setting their goals, there will likely be no commitment to them. There is no confusion about what needs to be done by when or whom. Chapter 14, “How to Compile and Assimilate a Bonus Performance Plan,” will provide you with examples of written win-win agreements we have helped firms create.

Customized Criteria and Goals

Owners and employees with valuable competencies outside the “minder, finder, grinder” criteria often were not motivated to exercise them because there was no reward for doing so. Many compensation systems paid little or no attention to managing the practice effectively or building future capacity in the firm. There were few, if any, incentives for an owner to cooperate with other owners, develop future leaders, or build new niches or services. Owners focused on how they could achieve their individual goals. Hence, firms created a culture of independence and competition: “I win, and I do not care whether you win or lose,” or worse, “I win, you lose.”

The focus today has begun to change. Firms are moving toward interdependent goals that develop a culture of cooperation, teamwork, and abundance. Studies have shown, and as Dr. Stephen R. Covey points out in The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, a philosophy of abundance, rather than one of scarcity, produces more for everyone. Success today is contingent upon owners acting interdependently rather than independently of each other. Compensation plans must take this into consideration.

Focus on Current Production and Future Capacity

We often tell our clients that no margin means no mission. Certainly, nothing is wrong with focusing on current production. After all, that is what helps create profits today. That focus, however, can become dysfunctional when current production is the only or primary focus.

Compensation plans need to encourage the accomplishment of current production goals, as well as goals that build the firm’s ability to get even better results in the future—developing capacity. These goals (for example, improving staff skills and creating more effective business systems, developing new service lines and niches, and so on) keep the firm capable of future growth. The ultimate, long-term success and viability of a firm depend upon the accomplishment of these two types of goals.

One chief operating officer of a top 100 accounting firm compared his firm to a sports team: “The team has an overriding vision and mission and needs to fill various spots with people who have different but complementary competencies. The more members work together, the more successful the firm becomes.”

Reward Performance, Not Entitlement

“What did you do for me today?” may be the emerging mantra. Seniority, equity, and lifelong credit for business origination no longer count as much as they once did in the scheme of total compensation.

The worst-case scenario of entitlement is one in which owners are compensated solely on seniority, equity, and even origination without regard to current production. For example, owner Jones has 40 percent ownership. The firm’s current compensation system provides for each owner to take out a draw of $100,000, and then, profits are allocated based on ownership. Jones’s other founding owner, Smith, has 38 percent ownership, and the 4 remaining owners have 7 percent, 6 percent, 5 percent, and 4 percent. Jones and Smith work the fewest hours and have the least billable time. In short, they are resting on their laurels. Because a large portion of their compensation is based on ownership, they are able to remain the highest-paid owners without contributing as much to the firm today. Younger owners could rightfully argue that both Jones and Smith have effectively retired from the firm but have failed to inform fellow owners.

Include At-Risk Compensation

A natural consequence to the current environmental and economic realities is that a lesser percentage of total compensation is guaranteed to owners. Not too long ago, an owner could often draw 90 percent or more of his or her total compensation. For example, an owner making $270,000 per year would be guaranteed $243,000. The amount at risk ($27,000) would be insufficient to motivate the owner to perform at a high level.

Today, that same owner might be guaranteed 70 percent or less of the total compensation, or $189,000 ($270,000 × 70%). In fact, some firms pay their owners less than 50 percent of their potential compensation during the year. In many large and midsized firms, base compensation is becoming a smaller percentage of total compensation. It is not unusual to find performance bonuses ranging from 30 percent to 40 percent or more of total compensation.

Ensure Fairness

We cannot tell you how many owners have pulled us aside to talk about the perceived lack of fairness of their current compensation systems. Recently, we were called into a firm to opine on the fairness of its compensation system. The owners themselves recognized the lack of fairness in the system but did not know how to go about addressing the salary discrepancy. We looked at total dollars collected by owners, total billable hours, and origination. Each owner, based on these three criteria, was contributing almost equally, but one owner was paid twice the other owners. Some of the owners, but not all, were taking on additional roles, such as marketing, training employees, and so on. We helped them determine a more equitable base salary for each owner and then set up a performance bonus plan that would reward those who achieved specifically defined goals.

Create a New Culture

The new compensation plan requires an examination and evaluation of the results that currently are being produced and an exploration of the individual behaviors that are causing those results. Then, you must explore why people behave the way they do. Generally, it is because they have found success with these behaviors in the past. When their behaviors, however, are not getting the desired results, you must explore even more deeply why they are engaging in behaviors that do not get the desired results. Remember, behaviors change only when individual attitudes and beliefs change. For example, if you believe business development is a noncore or uncomfortable activity, you will be less likely to engage in business development activities. The results will likely be very little or no new or cross-sold revenue.

Exercise Courage

Traditionally, owners have not been formally evaluated by management. According to the results of our compensation survey that appeared in Compensation as a Strategic Asset: The New Paradigm, 80 percent of firms indicated their owners do not have written goals. As a result, it is extremely difficult to have a formal evaluation process.

Underperforming owners are often retained because of close friendships or other emotional or subjective reasons. If there is no evaluation, it is easier for management simply to turn away rather than make a hard decision regarding the underperformer. Sadly, both the firm and individual owner lose. In a performance-based compensation system, underperformers have no place to hide because they have only three choices: accept compensation system changes, and strive to increase their performance; be asked to leave the firm; or elect to leave on their own accord. Remaining as an underperformer is no longer an option.

Final Thoughts

Times are changing, and now is the time to examine your views on compensation and income allocation. If you are not getting the financial results you expect, take a look at your compensation plan, and determine exactly what it is rewarding. You may find that it rewards the hoarding of clients rather than the sharing of clients or the hoarding of billable hours rather than pushing the work to appropriate levels. It may not encourage people in the firm to take risks or work on long-term projects, such as building new niches or developing new, more efficient systems.

The best advice we can offer you is to identify what is standing in the way of growing the compensation pie and using it as a true strategic asset. When you identify these barriers, as well as their negative effects, you can begin to develop a new and more effective compensation system for the firm.