CHAPTER 6

Managing and Monitoring Project Communications

The great enemy of communication, we find, is the illusion of it.1

—William H. Whyte, journalist and author

Now that you have planned your project communications, what’s next? To properly manage and carefully monitor your project communications! This chapter focuses on the next two processes in the PMBOK® Guide: managing and monitoring project communications. We will be looking at these areas through the lens of content presented throughout the book (Figure 6.1).

Figure 6.1 Manage and monitor communications

The purpose of this chapter is to help you:

• Build key skills needed to address stakeholders’ practical needs and personal needs when communicating on projects—including a five-step approach

• Measure the effectiveness of your project communications

• Understand the importance of incorporating feedback loops

• Examine lessons learned and retrospectives

• Put it into practice: Managing and monitoring communications in traditional, agile, and virtual project teams

Managing communications happens in the executing process group. This is when work is being done on the project. This is also the time when the project team is following their project communications management plan outlined in Chapter 5. Per the definition in the PMBOK® Guide, managing communications is “the process of ensuring timely and appropriate collection, creation, distribution, storage, retrieval, management, monitoring, and the ultimate disposition of project information.”2

Why is this important? Among the project team, we need to make sure that everyone who is working on the project is kept informed—that they have the information they need for successful completion of their assigned tasks and deliverables. Outside the project team, we need to ensure that stakeholders are also well informed—that they have the information they need to stay up-to-date and continue to support the project, or move from being unaware or resisting the project to a more supportive position (see Chapter 3).

Monitoring communications occurs in the monitoring and controlling process group. In earlier versions of the PMBOK® Guide (see Chapter 1), this process contained monitor and control communications. In the sixth edition of the PMBOK® Guide, the Control Communications process was eliminated since there are many things outside the purview of the project team that they cannot control, such as when, how, where, or why people communicate.3 However, there are still some elements of control in communicating on projects. While we may not be able to control everything— like when and how stakeholders communicate—we can control our reaction, attitude, approach, and response to their communications.

During monitoring communications, providing continuous oversight is necessary to constantly be aware of the communication taking place throughout the project, whether it is communicating about project status, activities, or results, or keeping stakeholders current with project information.

Over the life of the project, we should also seek opportunities to make improvements in our communications, processes, and environment. This can be done through feedback, surveys, ongoing conversations, etc.—various ways where we are asking for (and using) the valuable inputs and diverse perspectives of others. As the PMBOK® Guide clearly states, your project communications management plan should be revisited regularly and revised as needed.4 When the team receives input on implementing more effective ways of communicating with stakeholders, the project communications management plan should be updated to reflect this improved way of working.

And finally, we need to deliver project information in a way that influences and inspires, that reduces uncertainty and builds trust, and that grows the project knowledge and support of individuals and groups interested in our project at all levels, both inside and outside the organization.

Managing Project Communications

From a broad perspective, managing communications on a project means ensuring that the project communications management plan is being executed. In practice, managing communications starts with managing your conversations with all stakeholders. Ideally, your interactions end by accomplishing at least one of the following:

• Providing information needed to support the role of the person/group or their project needs

• Reducing their uncertainty about the project, their role, or others involved in the project

• Building their trust in the project’s goals, plan, and participants

So how do you effectively manage conversations? Let’s look at the conversation process developed by Development Dimensions International (DDI). DDI is a global leadership consulting firm that helps organizations hire, promote, and develop exceptional leaders. From first-time managers to C-suite executives, DDI is by leaders’ sides, supporting them in every critical moment of leadership. Built on five decades of research and experience in the science of leadership, DDI’s evidence-based assessment and development solutions enable millions of leaders around the world to succeed, propelling their organizations to new heights. For more information, visit https://www.ddiworld.com/.

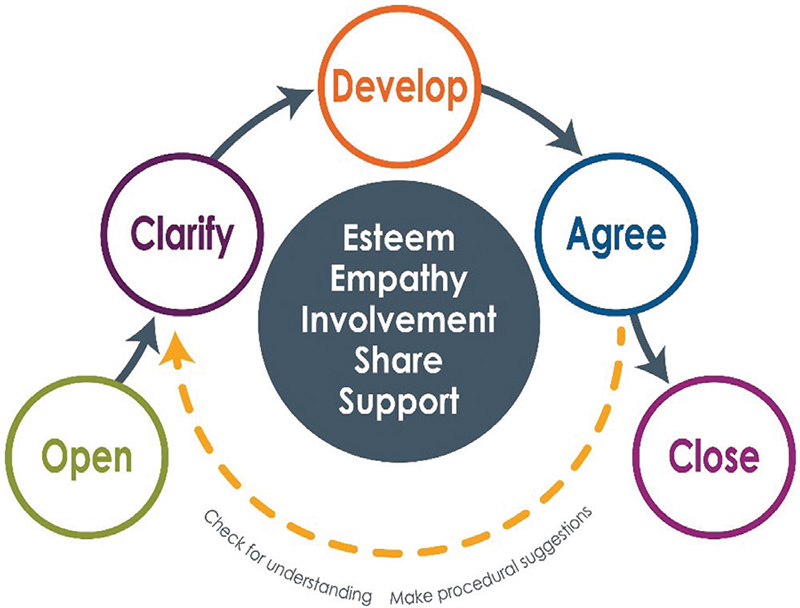

Through DDI’s years of extensive study and research, they found that “people come to work with both practical needs (to get work done) and personal needs (to be respected and valued).”5 The same is true with project teams. Team members are focused on getting the work done to achieve the project objective (practical needs) and to know that they are valued contributors and integral key members to the project team (personal needs). The skills used to meet the personal and practical needs in our communications are called “Interaction EssentialsSM.” Wouldn’t it be wonderful if all project communications were addressing both the personal and practical needs of the project team and stakeholders?

Personal Needs

Let’s start with managing project communications by addressing personal needs. This includes everyone inside and outside the project team who has an interest in our project. According to DDI, the five key principles are:

1. Self-esteem

2. Empathy

3. Involvement

4. Share

5. Support

Self-Esteem

By maintaining or enhancing self-esteem, we are managing communications by reassuring team members that they have the necessary expertise to be part of the team, by giving praise for doing a great job, or suggesting a better way of working.

To maintain self-esteem, we would have fact-based discussions (see Chapter 9), focus on the problem (not the person), and show our respect and support.

Example: “Joe, you have the most knowledge about the problem on this project. This project is very important to our customers. We really need your expertise in handling this situation.”

To enhance self-esteem, we would focus on recognizing great ideas and key contributions. This is an opportunity to build and show confidence in the project team member or stakeholder. In order to do this, we must be specific and sincere.

Example: “Sally, great job in speaking up today at the project team meeting to express your concerns with the project schedule. You are correct. It is very aggressive. Thanks for pointing this out. I really appreciate your ongoing contributions to the team.”

Empathy

By listening and responding with empathy, we are managing communications to build understanding, address the positive and negative emotions, and show that we care about others’ feelings while working with the facts.

Example: “Brian, I know this is a very large, complex project. You might be feeling a bit overwhelmed with doing all this project work, as well as getting your regular work done.”

Involvement

By asking for help and encouraging involvement, we are managing communications to seek ideas, ask for help, get commitment, and really be involved with the project and working together as a team. This is an opportunity to ask open-ended questions.

Example: “Maria, now that we have developed the project plan together, what are your thoughts? What does project success look like for you?”

Share

By sharing our thoughts, feelings, and rationale, we are managing communications to build trust. Trust is everything when it comes to working as a high-performing project team. To build trust, we must share our feelings, have open and honest communications, and discuss “why” decisions, changes, or actions are taken. The benefit of sharing is building relationships.

Example: “I understand how you are feeling. I had a similar experience working on a large, complex project, and worried about getting my regular work done. By developing a simple time management system, I scheduled time in my calendar to do project work, and time for my operations work. It worked for me. It might also work for you.”

Support

By providing support without removing responsibility, we are managing communications to build ownership. In managing projects, everything is “owned” by someone. When you own a task or responsibility, you are more likely to see it to completion and be successful. As the project manager, it is your responsibility to provide the necessary resources to help team members get their project tasks done and remove any obstacles that get in their way. With support, you are building confidence in others to be successful.

Example: “What can I do to help you? What is in your way of getting the project done? Perhaps there are some barriers that I can remove for you to be successful.”

Using these five key principles—self-esteem, empathy, involvement, share, and support—in managing project communications ensures that the personal needs of your project team and stakeholders are being addressed. That they feel “valued, respected, and understood.” How will you know their personal needs? For the project team, we suggest simply asking each team member. For outside stakeholders, we suggest identifying their needs during stakeholder analysis and documenting them in your stakeholder register as part of knowing your audience (see Chapter 3).

Practical Needs

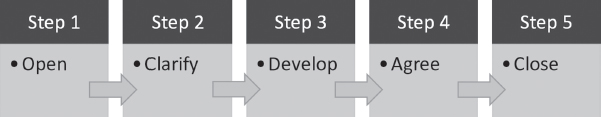

Now let’s look at the practical needs, which focus on a series of five steps. DDI’s research has proven that in order to have effective communications and conversations, there needs to be a structure to address the practical needs of individuals and stakeholders. DDI provides a “five-step conversation roadmap” called the Interaction Guidelines. Consider it as “a vehicle to frame conversations in a quick, logical, and thorough way—from start to finish—to cover all the specific information people need” on the project.6

This approach can be used with any conversation or interaction—any time—with anyone associated with the project. To meet the practical needs and to ensure that you have addressed all items that need discussing, the five steps in the Interaction Guidelines provide an excellent framework to follow. So, what are the five steps? They are:

Let’s take a closer look of each of the five steps, see how they relate to project communications, and explore an example of each.

The first step is OPEN. In this step, we address what the objective of this conversation is, and why it is important. Just like a “project objective,” you could consider this step as your “communication objective.” This is an opportunity to “open the dialogue.” For example:

Step 1: OPEN

• Today, I would like to hear your thoughts on how the team will achieve the project objective for the new accounting system. This new system will reduce our invoicing time by 30 days, and accelerate receiving customer payments.

The second step is CLARIFY. In this step, we are gathering information by seeking details and sharing data about the project problem. This is an opportunity to ask questions, to identify roadblocks, and reveal any concerns. This step is essential for establishing clarity and gaining mutual understanding. For example:

Step 2: CLARIFY

• We both agree that this is a very difficult project, and must be delivered on time, within budget, and according to project specifications. So let’s look at the facts that we have. I don’t want to miss anything.

The third step is DEVELOP. In this step, we are developing ideas, leveraging our creativity, utilizing the expertise of others, and discussing what resources and support are needed to make these ideas a reality. This is an opportunity for you (as the project manager) to also share your ideas and suggestions. For example:

Step 3: DEVELOP

• In order to achieve the project objective, we really need a high-performing project team. I would like to hear your ideas on this. What do you think it will take to be a high-performing team, and what additional resources do you think are needed?

The fourth step is AGREE. In this step, we are putting together our action plan with specific dates, details, and alternatives if needed. This is an opportunity to show commitment and how progress on the action plan will be tracked. For example:

Step 4: AGREE

• So let’s agree to meet every Monday morning at 9 a.m. to review the action plan together, and make any necessary adjustments. I will send a calendar request for our weekly meetings.

The fifth and final step is CLOSE. In this step, we want to summarize the important items that have been discussed, and to provide our support and encouragement. This is an opportunity to build confidence and trust. For example:

Step 5: CLOSE

• Let’s recap what we have decided. Do you have any questions?

• I have complete trust and confidence in you. I know that you will do an excellent job on this. You are the right person to handle this difficult situation.

Throughout the five-step process, make sure that you are also:

Checking for understanding. In project conversations, there is often a lot of information to share and discuss. Getting “off track” can easily occur which can create misunderstandings and confusion. During the discussion, use the opportunity to “check in.” Ask: “What have you just heard?” When someone repeats what you have said, this helps to check for understanding. (Later in the chapter, we will discuss seeking and giving feedback.)

Making procedural suggestions. In project conversations, we need to keep the discussion moving forward and on target. Remember that during Step 1, we stated the purpose and importance when we “opened” the discussion. In order to achieve your conversation objective, you may need to adjust the dialogue along the way.

Using this approach can help guide your project communications and discussions to achieve clarity, gain understanding, align expectations, and deliver better results.

Figure 6.2 shows how these two elements—personal needs and practical needs—work together and are “essential” to the internal and external communications on the project.

Figure 6.2 Interaction EssentialsSM developed by DDI. Reprinted with permission.

©Development Dimensions International, Inc., 1986. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission from Development Dimensions International, Inc.

Both of these questioning techniques can be used to provide a structure in managing communications within the project team (internal) or outside the project with stakeholders and other groups (external).7

Monitoring Project Communications

Monitoring communications in your project means evaluating the communications that are taking place, so that you can ensure you are achieving the intent of your project communications management plan. Even a project communications management plan that is executed fully, down to every e-mail and status report, may not be effective if the communications are not achieving their purpose. Two methods to do this are to measure the effectiveness of your project communications and to incorporate feedback loops.

Measuring the Effectiveness of Project Communications

Peter Drucker, well known for his innovative thinking in the way we do business, is often quoted as saying, “What gets measured gets managed.”8 So how do we measure the effectiveness of our project communications management plan? Are there specific communication feedback techniques that project managers commonly use? How do we measure the success of effective communications within project teams and with other stakeholders? What actions do we take when things aren’t working?

Great questions. Communication is known for being difficult to measure, as it is hard to prove a cause–effect relationship between communication and action. However, let’s see if we can take a closer look at measuring the effectiveness of our project communications with helpful steps that we can take as project managers, team members, and project sponsors.

Before you start evaluating the effectiveness of your project communication, you need to determine what, how, and when.

WHAT: What are you measuring? What are the criteria for the measurement?

Start with the outcome you desire to achieve. The purpose of your project communications is to keep all stakeholders informed so that the project progresses smoothly and ultimately achieves its objectives. Different elements of your project communications management plan will do this in different ways. Stand-up meetings (see Chapter 7) are meant to keep the team informed. Status reports keep stakeholders outside the project team apprised of progress. When deciding what to measure, revisit the specific goals of each tactic in your project communications management plan. You are looking to measure whether your project communications are meeting your stated goals.

HOW: How will you measure it?

Depending on what you define as your outcomes, there are several approaches to measuring communications:

Usage data: Technology applications lend themselves most readily to quantitative measures. Intranet sites can track analytics on who is using the site, how often, and for how long. E-mail marketing applications can track open and clickthrough rates. Online collaboration tools can track which team members are most active and where the most conversations are happening. Correlating this data with project deliverables and deadlines can potentially show areas where communications are, or are not, accomplishing the desired objectives.

Surveys: If you want to know if communications are working for the people who receive them, just ask. Surveys can range from simple feedback questions that provide qualitative and/or anecdotal information to more formal surveys with quantitative results. You can survey directly about project communications, or about desired outcomes like increased support for the project among stakeholders.

Planned versus actual communications: Your project communications management plan should outline your different communication tactics and how often you plan to use them—for example, status reports will be sent every 2 weeks. Measure how closely you are keeping to the plan and compare that with other project outputs. As with usage data, you may be able to correlate your communication efforts with positive or negative aspects of the project’s progress.

WHEN: When will you measure its effectiveness?

It is a good idea to start measuring early, and then measure frequently throughout the life of the project. If you don’t discover until the end of the project that your communications were ineffective, you have missed an opportunity—and possibly hindered your project’s success in the process. If your initial findings lead you to make changes to what or how you communicate, then measure again to ensure that the changes you made have actually improved your project communications. Project communications should be iterated and refined to ensure they are effectively informing all of your stakeholders.

Feedback Loops

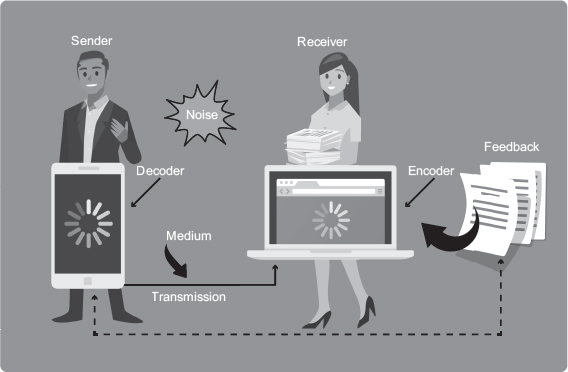

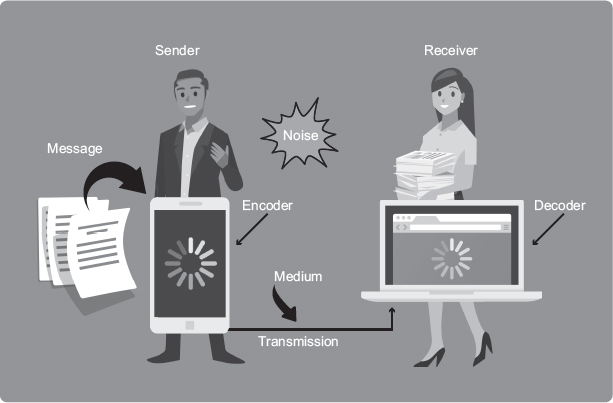

Communication is not a one-way street. Sending an e-mail, for example, is only half of the process. Have you ever sent an e-mail and not received a response? You might ask yourself, “Did the person receive my message? Did they read it? Did they understand it?” You are uncertain whether your message has been delivered because you have not gotten feedback from the receiver. Feedback from the receiver, such as a response to your e-mail, “closes the loop” between the sender and receiver of the message.

Why is a feedback loop important? It verifies that what you intended to communicate is what is actually understood by the receiver. Consider the basic sender–receiver communication model (Figure 6.3).

Figure 6.3 Basic sender–receiver communication model

• Sender: You are the sender, the person who initiates the message.

• Encoder: You type the message into the device (computer, phone, etc.) using text, numbers, symbols, etc. to create your message.

• Transmission: You send your message via some form of communication, such as e-mail.

• Noise: There are obstacles or barriers that could interfere with you sending your message, with the receiver not getting your message, or with the receiver not understanding your message. There can be many causes of noise, which vary from inadequate technology systems to lack of clarity in your message.

• Decoder: The receiver now has your message on his/her screen.

• Receiver: This is the person you intended to receive your message.

The feedback part of the process occurs in reverse, with the receiver responding to the sender to ensure that he/she actually understood what you intended to communicate. Figure 6.4 shows the sender–receiver communication model that includes the feedback loop.

Figure 6.4 Closing the feedback loop

Whether you are the sender or receiver of the message, one essential element in feedback is closure. Too often, there are items left unacknowledged, unclear, or unresolved in a conversation or interaction. For example: A stakeholder has a positive experience with a project team member and sends a note of recognition to the project manager. There is no response. Did the project manager receive it? Did he or she not agree with it? Does he or she have a conflict with the stakeholder? The item is left unresolved until the project manager responds. Even worse, the stakeholder has a negative experience because there is no feedback, which may cause the stakeholder to move toward resisting the project (see Chapter 3). This is why Step 5 (Close) in the conversation guidelines outlined earlier in this chapter is so important. We need to be crystal clear that the subject has been closed, agreed upon, and next steps decided.

How do you ask for feedback? According to Tom Peters, coauthor of In Search of Excellence, the “four most important words in management are…‘what do you think?’”9 These four words are critical in project communications. Asking people what they think is a powerful tool. It provides space for team members or stakeholders to address any remaining uncertainties they may have, and/or confirm their understanding of your message. It helps build trust by demonstrating that you value their personal and practical needs and want to ensure they are addressed by your message. Track the number of times you ask the project team or stakeholders, “What do you think?” It can make a big difference.

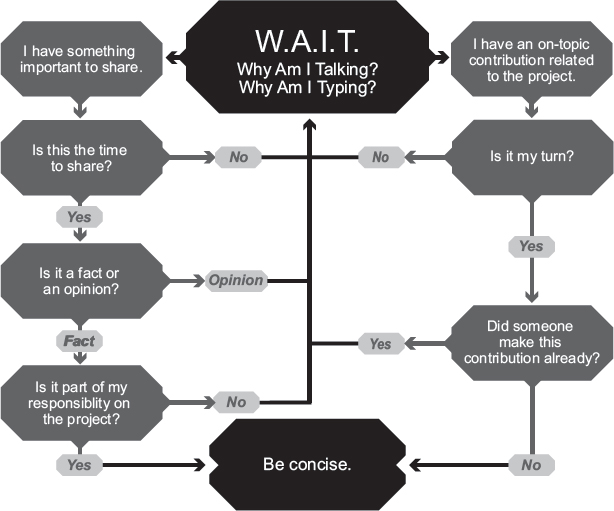

Finally, when engaging in a conversation or electronic exchange, check in with yourself using your own internal feedback loop. How can you be sure you are communicating what matters? Ask yourself: Am I adding value to this discussion? Is it a fact or my opinion? Is it relevant to the topic? Has someone already said this, and I am just repeating what someone else said? Consider Figure 6.5 which shows the concept of W.A.I.T., or Why Am I Talking? This concept can also be applied to Why Am I Typing? It can be a valuable exercise to help you determine whether your communications are purposeful.

Figure 6.5 W.A.I.T. Why Am I Talking? Why Am I Typing?

Lessons Learned and Retrospectives

In managing projects, we constantly hear, “document your lessons learned.” In agile project teams, lessons learned are called retrospectives. Regardless of the terminology, the key is to document and communicate what worked well and what needs improvement on the project. Simply writing these lessons down is not enough. They need to be used—by your team and by other project teams—to help avoid pitfalls and problems that have already been encountered, and to share effective processes and ideas so they can benefit future project teams.

When should you document (and communicate) lessons learned? Most often, teams do it (if at all) at the end of the project. Wrong. Lessons learned should be documented and communicated throughout the project. For example, in Week 3 of the project, the team experiences a situation that resulted in a “learning moment”—or a lesson learned. This is documented in their Week 3 status report and provides an opportunity to use this learning moment for the rest of the project. For agile projects, the team may conduct retrospectives at various intervals in the project. Regardless of timing, it is about reviewing, documenting, learning, and making improvements.

Lessons learned captured early in the project can ensure that positive results, such as a practice that works, are continued for the rest of the project. Or if there are lessons learned with a negative result, it could raise concerns to stop doing it, or make immediate adjustments, as the project continues. Either way, capturing and communicating lessons learned is a key element in managing and monitoring project communications.

Recall too that lessons learned can be about your project communications. Perhaps a team member missed a deadline because there were conflicting versions of a schedule and she looked at the wrong one. Or the sponsor came to you in a panic because he was asked for a project update and could not locate the most recent status report. Update your project communications management plan to prevent these issues from occurring again, but don’t forget to also document them as lessons learned. That way you won’t just improve your communications on this project, but on future projects as well—your own and others’.

Consider adding a “lessons learned” category to your status report. This way, key information and learning moments are documented throughout the project and can be easily referenced when the project closeout meeting occurs.

Putting It into Practice

Here are a few practical tips, fun activities, and useful ideas for how you can implement the concepts in this chapter into your project environment. Note that ideas listed in one type of team may be adapted to other teams. Be creative. Use these as a starting point. Add your own ideas to build your communications toolkit.

Managing and monitoring project communications |

||

|---|---|---|

Traditional project teams |

• Introduce the five-step approach to managing conversations to your project team. Conduct role-playing activities where each team member has the chance to be on the giving and receiving end of the conversation. • Set a feedback requirement with your team that all communications from other team members or stakeholders must be acknowledged within a set time limit (e.g., 24 hours). After 2 weeks, meet with the team and ask them to share the results and impact of using this technique. • Set up a reward system—gold stars on a publicly displayed board, points toward meaningful prizes, etc.—for team members who ask, “What do you think?” |

|

Agile project teams |

• Because of the rapid nature of agile teams, make sure you set aside time to close the feedback loop, and not leave items unresolved. • Look for simple ways to communicate status on your project. It saves time and reduces uncertainty. • Use retrospectives to measure the effectiveness of your communication activities and efforts. |

|

Virtual project teams |

• Virtual teams often use technology-based collaboration tools that provide analytics on usage. Find out the most active people and workstreams, and ask those team members why they are so active. Challenge less active team members or working groups to communicate more. • Develop a brief survey about communications on your current project, and send it to your stakeholders. In reviewing the results, take note of why some stakeholders may be more satisfied with project communications than others. • Post lessons learned in a searchable database with easy access for everyone. Organize content by categories with similar items grouped together for ease of reference. |

|

Summary

Once you have developed your project communications management plan, you are now ready to start using it to manage and monitor your project communications. Addressing the personal needs and practical needs of the project team and stakeholders is an excellent place to start. Have a structure for conducting your discussions so that you stay on track and achieve your communication objectives. Throughout your conversations or interactions, work toward ensuring understanding by all parties and make adjustments depending on the responses in the discussion or exchange.

To measure the effectiveness of your project communications, determine what you will measure and its criteria, how you will measure it, and when you will measure its effectiveness. Giving and getting feedback ensures what you intended to communicate is what is actually understood by the receiver. Asking questions like, “What do you think?” or, “What did you just hear?” are effective ways to get input and feedback. Use your own internal feedback process to make sure that you are adding value with each e-mail, meeting, or discussion. Documenting lessons learned and conducting regular retrospectives are essential in demonstrating if your project communications are working—or not.

Key Questions

1. In your project communications, how are you addressing the personal needs and practical needs of your project team members, sponsor, and stakeholders? Write them down.

2. Count the number of times you ask your project team members and/or stakeholders, “What do you think?” Track the results. Share with others.

3. What techniques are you using to measure the effectiveness of your project communications? List them. Note which techniques are working, and where changes are needed.

Notes

1. Whyte (1950), p. 174.

2. Project Management Institute (2017), PMBOK® Guide, 6th ed., p. 359.

3. Project Management Institute (2017), PMBOK® Guide, 6th ed., p. 647.

4. Project Management Institute (2017), PMBOK® Guide, 6th ed., p. 367.

5. Byham and Wellins (2015), p. 49.

6. Byham and Wellins (2015), p. 76.

7. ©Development Dimensions International, Inc., 1986. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission from Development Dimensions International, Inc.

8. Prusak (2010), https://hbr.org/2010/10/what-cant-be-measured.

9. Peters (2010), p. 155.

References

Byham, T. M. and R. S. Wellins. 2015. Your First Leadership Job: How Catalyst Leaders Bring Out the Best in Others. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Peters, T. J. 2010. The Little Big Things: 163 Ways to Pursue Excellence. New York, NY. Harper Collins.

Project Management Institute. 2017. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge. 6th ed. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

Prusak, L. October, 2010. “What Can’t Be Measured.” Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2010/10/what-cant-be-measured.

Wigert, B. and N. Dvorak. May, 2019. “Feedback Is Not Enough,” Workplace Newsletter, https://www.gallup.com/workplace/257582/feedback-not-enough.aspx.

Whyte, W. H. September, 1950. “Is Anybody Listening?” Fortune.