CHAPTER 9

Managing Conflict through Communication

Projects are, in their very nature, major sources of emotion.1

—Nicholas Clarke, management researcher, and Ranse Howell, conflict resolution expert

Projects are done by people. When there are people involved, there are emotions. Emotions readily lead to conflict. This means that conflict is likely to occur in almost every project, especially when stakes are high, resources are thin, budgets are tight, and time is limited. As your stakeholder analysis should reveal, everyone involved in the project has something at stake (see Chapter 3). When those interests contradict one another or are put in jeopardy (either in a real or perceived way), conflict occurs.

Unresolved conflict can be one of the biggest challenges a project team faces. It can lead to stress, negative attitudes, decreased commitment to the project, and ultimately project failure. Conflict resolution is therefore a critical project management skill—and a critical communication skill. It requires sensitivity, knowledge, and the ability to resolve the conflict in a timely, effective manner that enables the project to continue moving forward smoothly. This chapter offers conflict management strategies that build upon the project communication concepts already introduced in this book.

The purpose of this chapter is to help you:

• Examine two different types of conflict and how they can affect the project and the team

• Explore strategies for understanding and resolving conflict within the project team

• Consider ways to communicate with stakeholders when they do not support the project, when their expectations conflict with one another, or when the project deviates from the plan

• Put it into practice: Managing conflict through communication in traditional, agile, and virtual project teams

Sources of Conflict

Conflicts generally fall into one of two categories: interpersonal conflict and task conflict.2 These two sources of conflict are parallel to the two types of needs—personal and practical—that should be addressed when managing conversations, as discussed in Chapter 6. Interpersonal and task conflict have different origins, and can affect the team differently. Being able to identify which type of conflict you are facing can help you decide whether to intercede directly, and what to focus on if you do. Remember, however, that both types of conflict need resolution and effective communication. Further, a conflict that starts as one type can evolve into both types, especially when left unchecked.3

Interpersonal conflict, also referred to as relational or relationship conflict, arises from incompatibilities among team members based on individual factors like personality, values, background, behavior, or communication style. The team is a social structure made up of individuals working together, and it functions most effectively when all team members feel like they belong and are working toward a common goal. When interpersonal conflict occurs, it can impact the involved team members’ sense of team identity. They become uncertain about their place within the team and may start to withdraw, thereby undermining group efforts to get the project done. The conflict can also have negative effects on members of the team who are not directly involved.

Interpersonal conflict can be the most damaging kind of conflict. It takes time and effort to build relationships that result in optimal team functioning. However, conflict can damage those relationships very quickly. Once they are damaged, the relationships can take even more time and work to repair. According to research, it can take up to five positive interactions to overcome the damage of one negative interaction.4

Task conflict happens when team members have different perspectives on how to approach the work to be done. This can involve disagreements about distribution of resources, how tasks should be accomplished, or different interpretations of information. Task conflict occurs because team members come to the project from different personal and professional backgrounds, different units within the organization that have their own culture and approach to tasks, and/or different levels of project experience and expertise. These different influences lead team members to think about and approach tasks in different ways.

When people talk about conflict being good for teams, they generally mean task conflict. Different viewpoints and a wide range of experiences can reveal better ways to approach tasks that result in increased efficiencies in the project. This can lead to learning, creativity, and more flexibility in thinking.5 An example of this is when two project team members disagree on which process or method should be used to complete a project task. To make this conflict productive, the project manager can have the two team members present the pros and cons of their preferred solutions. This can help all team members better understand the implications of each choice and come to a well-informed decision; it can also improve team members’ communication skills and demonstrate the value of remaining open to new ideas.6

Table 9.1 provides an overview of the two types of conflict, their sources, and their effects on the project team.

Table 9.1 Interpersonal and task conflict

Type of conflict |

Sources |

Effects |

|---|---|---|

Interpersonal conflict |

• Source is unrelated to the team’s task • Emotional in nature • Arises from personal dislike, annoyance, personality incompatibility |

Negative: Can lead to decline in performance and productivity, withdrawal from collaboration, departure from the team, project failure |

Task conflict |

• Source is related to the team’s task • Cognitive in nature • Arises from difference in perspective |

Positive: Can lead to creativity, new solutions, more flexibility in thinking Negative: Can escalate and/or evolve into interpersonal conflict if unresolved |

Keep in mind, however, that there is a limit to the benefits of conflict. A review of research on both task and interpersonal conflict found that “whereas a little conflict may be beneficial, such positive effects quickly break down as conflict becomes more intense, cognitive load increases, information processing is impeded, and team performance suffers.”7 Thus, even productive conflict must be managed in order to maintain team cohesiveness and keep the project running smoothly.

Conflict within the Project Team

Effective conflict management has been shown to enhance team performance. Teams that are able to resolve conflict are more cohesive,8 and cohesion positively impacts perceived performance, satisfaction, and team viability.9

On the other hand, unresolved conflict can lead to team members’ dissatisfaction, decreased motivation and performance, frustration, anxiety, and even departure from the team.10,11 It can affect the project through misunderstandings about responsibilities, missed deadlines, lack of collaboration and decreased communication between team members, and unidentified inefficiencies that may result in the project exceeding its schedule and budget.12

The first step of managing conflict within the project team is knowing when to get involved. This can be a delicate balance for the project manager, who is responsible for the project and for leading the team, but most likely does not have functional authority over project team members. You should consider interceding if:

• you believe the conflict is having or will have a negative effect on the project,

• the conflict involves you directly, or

• anyone involved in the conflict comes to you for advice or help.

Carefully weigh whether you should involve other organizational resources. If the conflict involves a team member’s responsibilities on the project interfering with their other functional responsibilities, it may be prudent to communicate with or involve the individual’s functional manager. If the conflict is interpersonal and highly emotional, you may want to consult human resources before proceeding.

When you do step in to help manage conflict, remember this basic rule: Focus on the project or the problem, not the person! While there are a number of conflict resolution strategies and approaches available, many involve some aspect of the following three steps: de-escalate, redirect, and exit.13 You may recognize aspects of the five-step approach to managing conversations we introduced in Chapter 6. Note that this approach can be applied whether you are involved in the conflict directly, or are mediating a conflict between others.

Focus on the project or the problem, not the person!

Step 1: De-escalate

Managing emotions is particularly difficult in conflict—these situations can elicit physiological responses that are difficult to control, such as increased heart rate, sweating palms, or tensing muscles. These are symptoms of the fight-or-flight response, and they happen because the subconscious mind can interpret conflict as a threat. They also interfere with the part of the brain that controls rational thinking. As a result, individuals in conflict may raise their voices or bring up unrelated or unproductive issues in an attempt to attack the other person. This pattern of communication and behavior does not resolve the conflict, and ends up damaging relationships between team members.

De-escalating the conversation is an effort to avoid additional damage to the team members’ relationships. As noted earlier in this chapter, damaged interpersonal relationships can be difficult to repair, and can have a detrimental effect on the project. Remind involved parties that, “The person in front of you is more important than the feeling inside of you.”14 Ask them to focus their words on the situation at hand, rather than on any personal comments, attacks, or blame.

Take a break if necessary, especially if emotions are high. Stopping for a few minutes can give everyone a chance to process their emotions, and allow physiological fight-or-flight responses to diminish. Call for a break—to get a drink of water, use the restroom, or get some fresh air—and give everyone an opportunity to come back to the conversation with clearer heads.

Bring the conversation back to the issue at hand. Intensified conversation (e.g., raised voices, unproductive criticisms or insults, etc.) is not the same as important communication—the intensity becomes what’s important instead of the source of the conflict.

First, clarify the facts. Some conflict can be resolved simply by giving both sides the full picture of what happened. Next, clarify intent. People often make assumptions about intent; they assign specific intentions to another person’s words or actions.15 For example, “He e-mailed you about my work being late because he was trying to undermine me and make himself look good at my expense.” Give each party the opportunity to explain their intent to dispel any assumptions. Conflict, after all, often arises from uncertainties; by helping to reduce or manage these uncertainties, you can reduce or manage the conflict they have sparked.

Skip the blame and focus on the outcome. Clearly communicate that your goal is to resolve the conflict in a way that allows the entire team to move forward together to accomplish the project objective. In conflict, people frequently get hung up on the idea of assigning blame. For example, “This deliverable is late because she didn’t get to me report on time.” In general, people do not like to acknowledge that they have done something wrong and are at fault or partially at fault. They are uncertain about the consequences, fearing negative repercussions that range from being viewed as incompetent, to losing their job.16 Make it clear what the consequences are, if any; this will reduce uncertainty and allow those involved to move forward in the resolution process. Then, work on the outcome with input from all parties, which should focus on compensating for any problems or issues that have affected the project, and putting mechanisms in place to attempt to prevent the issue from occurring again.

Step 3: Exit

Once a resolution has been found, make sure both parties accept it. Give each of them an opportunity to communicate any additional thoughts or concerns, so that you can be sure the conflict is truly resolved. If the situation has impacted the project, make the necessary updates to the project plan, schedule, or other project documents. If appropriate, add it to your lessons learned document as well.

If you are unable to come to a satisfactory resolution, ask the involved parties to table the issue for now. This gives you the opportunity to step back from the conflict and consider more potential solutions. You may want to call upon additional resources such as functional managers, subject matter experts, human resources personnel, the client or sponsor, or other stakeholders for input on the best way to resolve the issue. Be sure to set a time to reconvene, so that everyone has a clear expectation about when the issue will be addressed again.

Conflict resolution can be very challenging. It is not an easy skill to develop, and often requires individuals to engage in difficult conversations. It is, however, an important skill for project managers and team members. As we stated at the beginning of this chapter, unresolved team conflict can be one of the biggest challenges a project team faces. Resolved conflict, meanwhile, carries benefits beyond renewed smooth progress on the project. Successful conflict resolution can also help build team cohesion and trust, more so than if conflict had never occurred in the first place.17

QTIP

We often struggle with conflict because it can impact how we see ourselves. Someone may criticize a specific task—for example, a project report that missed a key piece of information—and we subconsciously generalize it to be a critique of who we are: “I am incompetent.” We take the situation personally, which makes it far more difficult to resolve the conflict.18

One simple, visual tool that can help you and your project team remember to fight this tendency is a cotton swab, known in the U.S. by its brand name, Q-tip®. This brand name is also an acronym for Quit Taking It Personally. Early in the project, set aside a few minutes to relay this advice and hand out cotton swabs to everyone on the team. Ask them to keep their cotton swabs somewhere visible as a reminder of this important lesson—don’t take it personally, focus on the project.

Managing Conflict with Stakeholders outside the Project

As we’ve seen so far in this chapter, managing conflict within the project team involves direct conflict management approaches and skilled communication. The goal is to preserve team cohesion and come to an agreement on the best way to resolve the conflict so that the team can move forward in achieving the project objectives. However, conflict outside the project team can materialize in very different ways that may require different approaches. Here are three common scenarios where you must work through conflict with stakeholders outside of the project team:

1. Working with stakeholders who are resistant to the project

2. Communicating project setbacks to stakeholders

3. Handling conflict between project stakeholders

When Stakeholders Do Not Support the Project

Many projects, especially those that can significantly disrupt “business as usual,” will likely have stakeholders who do not support the project. In Chapter 3, we examined the spectrum of stakeholder support, from unaware or resistant to supportive or leading. Those on the resistant side of the spectrum may say or do things to weaken support for, or even interfere with, the project. The PMBOK® Guide addresses this issue under the process of Manage Stakeholder Engagement, part of the Project Stakeholder Management Knowledge Area. “The key benefit of this process is that it allows the project manager to increase support and minimize resistance from stakeholders.”19

Once you identify stakeholders who may be resistant to your project, the following recommendations may help minimize their resistance, reduce the likelihood of conflict or its intensity when it arises, and even move them toward being more supportive of the project:

Communicate early and frequently. Keep resistant stakeholders in the loop. This can help build trust by demonstrating that you understand and respect their interest and/or impact on the project, and want to engage with them despite their disposition toward the project. Build these communications into your project communications management plan.

Seek feedback regularly. Check in with these stakeholders either with a set frequency (e.g. monthly) or at project milestones. Encourage honest feedback, and provide direct responses to their concerns to the greatest extent possible. (See Chapter 6 for more on seeking feedback.) Don’t forget to refer back to your stakeholder analysis and project communications management plan when communicating with stakeholders.

Get the stakeholder involved. If the stakeholder is particularly resistant, or if you are not successfully able to address their concerns on your own, engage them in working with you toward a solution. Get their input on what it will take to reduce or resolve their resistance to the project, and then ask them to help in putting that solution into practice.

Give these strategies a try, and make the necessary adjustments when needed.

Giving Stakeholders Bad News

Another stakeholder situation that may involve conflict is having to communicate bad news to key stakeholders who have a high level of interest and/or investment in the project. For example, a problem may materialize that results in project work needing to be done over, causing a delay in the project schedule. How do you communicate this news that key stakeholders may not want to hear, and may react poorly to? What you say is important, but so is when and how you say it.

What you say is important, but so is when and how you say it.

Here are some recommendations on how to conduct these difficult conversations.

What: Focus on what happened, how it impacts the project—cost, schedule, scope, etc.—and how it is going to be corrected and prevented moving forward. Give a clear explanation of the problem and why it occurred. Do not focus on who is at fault; instead, focus on how you plan to fix the problem and/or prevent it from recurring, and how you will minimize the negative impact on the project. Some of this may already be addressed in your risk management planning.

When: The higher the stakes, the sooner you should tell the stakeholder(s). In some cases, immediate action can help mitigate the effects of the problem. As soon as you understand the source and impacts of the issue and have identified a plan of corrective action, talk to the stakeholder. If you are not able to propose corrective action immediately, you will still want to inform the stakeholder and ask for their support in developing a solution.

How: Negative news should be delivered in person, or at least through a real-time, two-way channel such as a telephone call or video call. This can be intimidating because the stakeholder may not react well to the news, regardless of how supportive of the project they may be. Despite this possibility, do not use an asynchronous communication channel like e-mail or text. Real-time conversations allow the stakeholder to ask questions, show them that you are accountable for the project, and help preserve trust and relationships despite the problem at hand.

The conflict resolution steps noted above can be useful to help navigate difficult conversations like these. If the stakeholder does react poorly, focus first on de-escalating the interaction. Keep the focus on resolving the issue and honestly answering the stakeholder’s questions. When you conclude the conversation, reinforce your commitment to correcting the action, and affirm the stakeholder’s buy-in to the solution and the project as a whole.

Once the issue is addressed, don’t forget the follow-up. Continue to keep affected stakeholders apprised with updates on the proposed solution and its effectiveness. This can be done through ad hoc communications when necessary, or within planned communication methods like status reports. Finally, identify and document the lessons learned. This will benefit you, the project, and the project team going forward to prevent or mitigate similar issues from affecting this project as well as future projects. And don’t forget to update your project communications management plan as needed.

Managing Conflict between Stakeholders

Stakeholders have different expectations and priorities for projects—this is the “what’s in it for me”, or WIIFM concept that we discussed in Chapter 3. The sponsor may be most concerned about the project staying within budget, while operational groups who will use the results of the project may be most concerned about the project finishing on time. Sometimes, it may not be possible to meet both stakeholders’ expectations completely. Conflict may result that can jeopardize the project’s progress and potential for success.

Interpersonal conflict can also occur between stakeholders, just as it can occur among members of the project team. Potential areas for interpersonal conflict can be identified as you conduct a thorough analysis of your stakeholder audience, including role, power and influence, level of support, and priorities and expectations. This is also an area where expert judgment can be useful. As noted in the Project Stakeholder Management Knowledge Area of the PMBOK® Guide, expert judgment can identify considerations around political and power structures in the organization and among stakeholders, organizational culture and environment, and knowledge from past projects and stakeholder interactions that may influence the current project. Finally, when talking with stakeholder groups, listen closely for any clues that may indicate conflict with other stakeholders. A member of the executive team may remark that he has had a past negative experience with a resource manager or a vendor. Note these potential issues so that you can be on the lookout for conflicts that may arise.

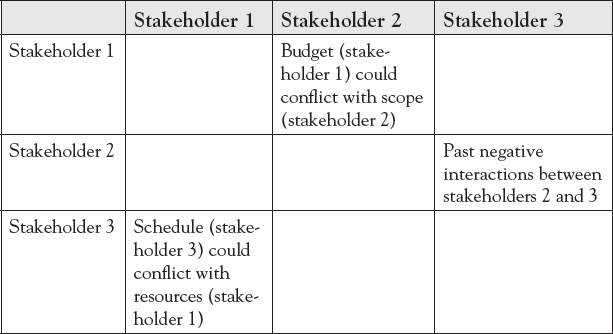

As you identify stakeholder priorities and document them in your stakeholder register, spend some time reviewing where expectations or personalities may conflict. Depending on the size and complexity of your project, you may want to ask the project team to contribute to this exercise as well. A simple tool like the stakeholder conflict template in Table 9.2 may help.

If conflict occurs between stakeholders, address it early to prevent it from escalating and putting the project at risk. Communication approaches such as the five-step technique for managing conversations outlined in Chapter 6, or the more basic three-step approach to addressing conflict noted earlier in this chapter, may be sufficient to mitigate the conflict. However, because project managers and team members have no functional authority over most stakeholders, seeking support from other organizational resources such as project leadership, senior management, or human resources may be necessary.

In any given project, there’s a good chance something will not go according to plan. Sometimes these are identified risks that materialize, and sometimes they are unexpected. No matter what the issue, conflict can result. Using effective communication strategies like those discussed in this chapter can have a major impact on how the conflict affects the project, and on your reputation and effectiveness as a project manager. Remember: It’s not about whether things go wrong, it’s about how you handle them when they do.

Table 9.2 Stakeholder conflict template example

Putting It into Practice

Here are a few practical tips, fun activities, and useful ideas for how you can implement the concepts in this chapter into your project environment. Note that ideas listed in one type of team may be adapted to other teams. Be creative. Use these as a starting point. Add your own ideas to build your communications toolkit.

Managing conflict through communication |

||

|---|---|---|

Traditional project teams |

• At the end of an intense discussion or meeting, ask each participant to share something positive about themselves—or someone else on the team. • Encourage/reward conflict that is handled appropriately. Look for opportunities to positively acknowledge team members who do so. • At the beginning of the project, send a brief survey to each team member asking them how they feel about conflict. Use the results (without revealing names) to facilitate a discussion on how you expect conflict to be handled on the project. Add the discussion outcome to your team operating principles. (This is a good time to introduce the QTIP lesson.) |

|

|

• Effectively utilize an agile coach (or agile mentor) to help agile team members deal with conflict. An agile coach who is experienced in people skills and agile practices and processes can help team members through challenging times and situations. • When conflict occurs, look for the root cause and address it quickly. Otherwise, it will slow down the rapid progress and results that agile teams desire. • Encourage servant leadership of coaching, mentoring, collaborating, communicating, and helping others. This is the best way to reduce conflict and keep the team moving forward. |

||

Virtual project teams |

• Virtual teams often exhibit more cultural diversity, as team members may be spread across the globe. Ask each team member to share something about their culture with the group. • When you do hold in-person meetings with virtual teams, be sure to incorporate some hands-on team-building activities. The project may seem like the priority, but that can be done virtually. Use face-to-face time to build relationships and trust among the team. • Conflict creates tension and can multiply rapidly when not properly or quickly addressed. When conflict occurs, it may be necessary to travel and meet with the stakeholder or team member(s) in person. This shows your attentiveness to the situation and willingness to achieve resolution so that the project and team can succeed. |

|

Summary

Since projects are done by people, conflict is likely to occur. This is where your communication skills are most needed to effectively manage conflict within the project team and among stakeholders outside the team. There are two sources of conflict: interpersonal conflict (relational conflict) and task conflict (objective disagreements). Task conflict can be a good thing. Positive conflict can be the foundation for stronger relationships and greater results. Interpersonal conflict and unresolved task conflict, however, can have negative effects on the project and the team.

Project professionals handle and manage conflict through various communication strategies. Handling conflict within the project team requires knowing when to intercede, and how to address the situation when you do. Project teams who are able to resolve conflict quickly and effectively are more cohesive and achieve greater results than those teams who let conflict go unresolved, hindering project and team success.

Conflict with stakeholders outside the project team can occur when stakeholders are unsupportive of the project, when you must communicate problems or delays in the project to the stakeholder, or when two different stakeholders have conflicting expectations or personalities. Respond to these situations quickly, honestly, and with support from organizational resources when necessary.

When addressing conflict, you may find some strategies work, and other approaches need to be modified, based on the situation and people involved. Make the necessary adjustments in your communications—with the goal of conflict resolution. And don’t forget the QTIP: Quit Taking It Personally.

Key Questions

1. Think back on your project experiences where conflict has occurred. Was it task conflict or interpersonal conflict? How was it handled? If it occurred again, what would you suggest be done differently?

2. When you have experienced conflict on a project team, what communication strategies have you used? What adjustments to these strategies have you made?

3. What benefits have you experienced or seen from positive conflict on a team? What challenges have you experienced or seen when conflict goes unresolved?

Notes

1. Clarke and Howell (2009), p. 4.

2. Chen (2006), p. 107.

3. Chen (2006), p. 111.

4. Tumlin (2013), p 50.

5. Chen (2006), p.107.

6. Estafanous, 2018.

7. De Dreu and Weingart (2003), p. 746.

8. Nesterkin and Porterfield (2016), p 15.

9. Tekleab, et al. (2009), p. 194.

10. Jehn (1994).

11. De Dreu and Weingart (2003).

12. Susskind and Odom-Reed (2019).

13. Tumlin (2013), p. 67.

14. Tumlin (2013), p. 62.

15. Stone, et al. (2010), p. 11.

16. Stone, et al. (2010), p 12.

17. Tekleab, et al. (2009), p. 171.

18. Stone, et al. (2010), p. 14.

19. Project Management Institute (2017), PMBOK® Guide, 6th ed., p. 523.

References

Alexander, M. July 1, 2015. “7 Tips to Transform Difficult Stakeholders into Project Partners.” CIO, https://www.cio.com/article/2942210/7-tips-to-transform-difficult-stakeholders-into-project-partners.html.

Alexander, M. December 29, 2016. “8 Steps to Breaking Bad News to Difficult Project Stakeholders.” TechRepublic, https://www.techrepublic.com/article/8-steps-to-breaking-bad-news-to-difficult-project-stakeholders/.

Chen, M. H. 2006. “Understanding the Benefits and Detriments of Conflict on Team Creativity Process.” Creativity and Innovation Management 15, no. 1, pp. 105–116.

Clarke, N. and R. Howell. 2009. Emotional Intelligence and Projects. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

De Dreu, Carsten K. W., and L. R. Weingart. 2003. “Task Versus Relationship Conflict, Team Performance, and Team Member Satisfaction: A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Applied Psychology 88, no. 4, pp. 741–749.

Estafanous, J. October 27, 2018. “Why Your Team Needs Conflict and How to Make it Productive.” The Startup, a Medium Corporation. https://medium.com/swlh/why-your-team-needs-conflict-and-how-to-make-it-productive-8475da62282c, (accessed September 7, 2019).

Gallo, A. December 1, 2017. “How to Control Your Emotions During a Difficult Conversation,” Harvard Business Review, https://hbr.org/2017/12/how-to-control-your-emotions-during-a-difficult-conversation.

Jehn, K. A. 1994. “Enhancing Effectiveness an Investigation of Advantages and Disadvantages of Valuebased Intragroup Conflict.” International Journal of Conflict Management 5, no. 3, pp. 223–238.

Krumrie, M. 2019. “How and When to Manage Conflict.” Monster.com, https://www.monster.com/career-advice/article/managing-conflict-how-and-when, (accessed September 7, 2019).

Lalegani, Z., A. N. Isfahani, A. Shahin, and A. Safari. 2019. “Developing a Model for Analyzing the Factors Influencing Interpersonal Conflict.” Management Decision 57, no. 5, pp. 1127–1144.

Lee, S., S. Kwon, S. J. Shin, M. Kim, and I.-J. Park. 2018. “How Team-Level Conflict Influences Team Commitment: A Multilevel Investigation.” Frontiers in Psychology, 8, pp 1–13.

Nesterkin, D., and T. Porterfield. 2016. “Conflict Management and Performance of Information Technology Development Teams.” Team Performance Management 22, no. 5/6, pp. 242–256.

Porter, T. W., and B. S. Lilly. 1996. “The Effects of Conflict, Trust, and Task Commitment on Project Team Performance.” International Journal of Conflict Management 7, no. 4, pp. 361–376.

Project Management Institute. 2017. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge. 6th ed. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

Semeniuk, M. February 24, 2010. “Running with Scissors: Techniques for Managing Conflicting Expectations.” Paper presented at PMI® Global Congress 2010—Asia Pacific, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, https://www.pmi.org/learning/library/managing-conflicting-expectations-6893.

Stone, D., B. Patton and S. Heen. 2010. Difficult Conversations: How to Discuss What Matters Most. 10th anniversary ed. New York, NY: Penguin Group.

Susskind, A. M., and P. R. Odom-Reed. 2019. “Team Member’s Centrality, Cohesion, Conflict, and Performance in Multi-University Geographically Distributed Project Teams.” Communication Research 46, no. 2, pp. 151–178.

Tekleab, A. G., N. R. Quigley, and P. E. Tesluk. 2009. “A Longitudinal Study of Team Conflict, Conflict Management, Cohesion, and Team Effectiveness.” Group & Organization Management: An International Journal 34, no. 2, pp. 170–205.

Tumlin, G. 2013. Stop Talking, Start Communicating. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education.

Villax, C., and V. S. Anantatmula. July 14, 2010. “Understanding and Managing Conflict in a Project Environment.” Paper presented at PMI® Research Conference: Defining the Future of Project Management, Washington, DC, https://www.pmi.org/learning/library/understanding-managing-conflict-resolution-strategies-6484