7

Enabling sustainable behaviours through m-commerce app design

Focus on the fast fashion industry

1. Importance of m-commerce in the fast fashion industry

The world is changing faster than ever, driven by globalisation and continuous technological development. This chapter contributes to knowledge by proposing app design elements to allow retailers to clearly communicate their sustainable practices and values to consumers, while simultaneously engaging consumers in a unique shopping experience driven by an emotional experience.

A study by Delloitte (2016) revealed that people in the UK have never been more addicted to their smartphones, with almost 52% checking their devices within the first 15 minutes of getting up, and 43% just 15 minutes before turning in for the night. Seeing as smartphone penetration achieves an all-time high of approximately 81% (Statista, 2017), mobile-commerce (m-commerce) needs to be considered as a key communication channel for the fashion industry. The increased use and exposure of technology provides retailers not only with an opportunity to reach a wider target audience almost instantaneously, but also creates a platform for dialogic communication. Aspects of sustainability have increasingly dominated the latter.

In this chapter, Design Thinking, (a process that describes the way designers create solutions to complex problems) was used to develop the concept retail app design. This process is typified by the stages of (1) understanding (asking how the problem can be solved), (2) observing (understanding the users and their needs), (3) point of view (evaluating information presented), (4) ideation (creating multiple solutions), (5) prototyping (developing paper prototypes of concepts) and (6) testing (engaging potential users in simulated interactions to gauge their response (Dorst, 2011; Leavy, 2010).

2. Understanding: sustainability and m-commerce in the fast fashion industry

Why look at the fast fashion industry, sustainability and m-commerce? Bhamra and Lofthouse (2007) commented that organisations need to incorporate sustainable behaviour into their business models and practices in terms of natural, human, social, manufactured, and financial capital. However, the fast fashion business model has often been criticised, as it fosters unsustainable behaviour such as hyper-consumption and a throwaway culture (Bédat, 2016; Siegle, 2014). The ever-increasing speed of the fashion life cycle, with companies producing new styles and fashion lines every fortnight, has contributed to the fashion industry being not only the second most polluting industry globally (Conca, 2015), but also one that has received continuous negative press especially surrounding its labour practices not only internationally (Parveen, 2014), but more recently nationally, when a documentary uncovered sweatshops in the UK (Channel 4, 2017). Yet, against this bleak backdrop, the fashion landscape has seen dramatic changes within the past decade, which has been fostered by sustainability emerging as a ‘megatrend’ (Mittelstaedt, Shultz, Kilbourne, & Peterson, 2014), with companies seeking to demonstrate their commitment to sustainability (social, economic and/or environmental) as ‘good corporate citizens’ (Aßländer & Curbach, 2014; Henninger, 2015; Henninger, Alevizou, & Oates, 2016). Consumers are increasingly aware of the effects the fashion industry as a whole has on the natural and social environment and thus, demand for sustainability practices to be implemented. Companies respond to this requirement through creating corporate social responsibility (CSR) strategies, which demonstrate their commitment to sustainability. Aspects of CSR are strongly featured in the companies’ communication strategies and ultimately disseminated through their various communication channels. Yet, a key question that emerges is in how far consumers decode sustainability messages. More specifically, with fashion m-commerce increasing in popularity, it is vital to understand how sustainability messages cannot only feature on these platforms, but also be made acceptable.

Over the past two decades, fashion m-commerce, a term coined by Duffey (1997), has increased in importance and is a vital touch point between the organ-isation and the consumer. M-commerce is irreversibly linked with international commerce, representing 11% of all UK retail (Mercer, 2014), with over 87% of all smartphones and tablets being used for online shopping (The Nielsen Company, 2014). Furthermore, extant research (The Nielsen Company, 2014) indicates that m-commerce delivers potentially the most seductive and emotional platform for purchase behaviour to date, which provides an opportunity for organisations to foster their sustainable image and enhance this emotional bond. There is a real potential for companies to capitalise on establishing their image as ‘good corporate citizens’ and working together with increasingly environmentally and socially conscious consumers. Millennials (also known as Generation Y or generation scroll, like, and share) are very active on m-commerce platforms and increasingly concerned with aspects of sustainability. This provides an opportunity for academics and practitioners to examine and develop mobile apps and their ability to connect with an increasingly ‘online’ generation and communicate aspects of sustainability.

3. Observation: sustainable apps and behaviours

Despite sustainable fashion being over 30 years old (with retailers including Patagonia and ESPRIT bringing sustainability into their business model in the 1980s), the concept has yet to find an impact on the Apple or Android app stores for established fashion brands. For example, ASOS (2017) stocks 15 products discoverable under the search term ‘eco’, but when compared to the search term ‘red’ returning 5,025 results, the low frequency of items is clear. Furthermore, ASOS – and other analysed high street retailers including Hugo Boss (2017) – did not provide any search or filter features for sustainable products. This represents a low degree of assisted discoverability for the user in the app’s design, an element that should be key to successful interaction (Preece, Rogers, & Sharpe, 2015).

Consequently, only the most motivated and sustainably conscious shoppers are likely to discover sustainable products. Outside of the established retailers, there are examples of dedicated sustainable fashion online platforms – e.g. People Tree (Poq Studio, 2016) and Better World (WebHouse, 2017) – and through ‘sustainable social network apps’; e.g. GreenApes (2017). While these platforms have the potential to grow and be part of the ecological solution, without high-level financial investment (De Chernatony & McDonald, 2003), this is unlikely to happen. This is in every way a non-trivial barrier to diffusion of the innovation, exemplified by GreenGlamGo (2011), an app that promised to overcome this challenge by providing a list of retailers committed to sustainability and their products. The visuals incorporated in the app allowed for ease of use and clearly highlighted where these products could be purchased. However, this app was based on the now defunct Symbian mobile OS, with the company folding soon after launch, highlighting great potential yet non-significant impact in the fashion retail world.

When seen in relation to the behaviour model of Fogg (2009), this suggests that unless the app design is altered to facilitate sustainable garment discovery within such apps, sustainable fashion purchase behaviours are unlikely to become common within the general population. Just as each sensory interaction with a brand’s touch-point (e.g. visual adverts, in-store atmospherics, app landing page, etc.) presents an opportunity to construct a ‘story’ about the brand in the mind of the customer (Berger & Luckmann, 1966), each touchpoint within an app provides an opportunity to promote and include sustainability in a way that is currently not enacted.

4. Point of view: sustainable consumer behaviour

Henninger (2015) found that consumers are price conscious, especially within the fashion industry. Fashionistas are trend-led and want to be it (up-to-date, fashionable, trendy), thus the assumption that green/sustainable fashion does not only come at a price premium, but also is associated with being less fashionable, provides a key challenge for organisations. Consumers have indicated that sustainable fashion products are not always well labelled and lack mainstream availability.

Lejeune (2016) indicates that ASOS started to distribute sustainable fashion and dedicates a section on their website to this type of fashion, yet looking at the mobile app, only consumers that know what they are looking for will be able to find the Eco Edit section within the ‘Brands’ category. It could be argued that having Eco Edit within the ‘Brands’ section is also misleading, as consumers may not be aware that it incorporates a conglomerate of designers and retailers that produce sustainable fashion. Authors (Joergens, 2006; Shen, Zheng, Chow, & Chow, 2014) have highlighted that a key challenge faced by the fashion industry in an online and offline context is being able to identify sustainable fashion and making it ‘visible’ to consumers. Thus, it is vital for a sustainable fashion app to clearly highlight what is being sold and where and making it easy for the consumer to navigate the platform.

Netter (2017) further highlights that key aspects of apps that need to be considered in the design process are (1) actual design (ease of use, speed, structure, visuals and compatibility), (2) reliability of the information provided, (3) responsiveness when something goes wrong with the app, (4) assurance (up-to-date information, confidence, ability and safety) and (5) empathy (personalisation). Millennials are sophisticated consumers, who are tech savvy and are easily bored (Zimmerman, 2016), thus, interactivity is key. GreenApes (2017) allows consumers to share their sustainable actions with a wider audience, while at the same time earning rewards, such as discount vouchers for sustainable fashion stores, free desserts at sustainable restaurants, or reduced entry fees to leisure facilities. Consumers are actively encouraged to participate in sustainable practices, which are linked to other mobile apps, while at the same time educate consumers about the positive impact their behaviour has on the natural and social environment. Sharing mechanisms, such as liking pictures, tweeting information or ‘Instagramming’ photographs actively encourages knowledge exchange and can enhance sustainable behaviour (Char-band & Jafari Navimipour, 2016), thus, should be incorporated as a vital feature of any sustainable app design.

5. Design brief

From the first three stages of Design Thinking within this chapter (understanding, observation, and point of view), it is clear that while sustainable fashion is an option for consumers shopping for fast fashion and high street stores, discoverability and visibility of sustainable garments is the missing keystone. In order to facilitate motivated customers to discover and consider sustainable purchases, the concept retail app within this chapter needs to focus on the facilitated discoverability of sustainable fashion, and enhancement of consumer awareness that such options exist as a retail option.

Furthermore, it is important that any designs adhere to fundamental app design principles that encourage positive attitudes and actions towards sustainability. As Fogg (2009) highlighted, an interface intended to direct a person towards a chosen behaviour must facilitate that behaviour by making it easy to engage in, with little motivation and to have triggers to suggest action on behalf of the user. While more design principles exist for creating engaging user behaviours, this chapter focuses on the five most prevalent dimensions that must be applied to both triggers and facilitators in order for a sustainability approach to be successful:

- Be glanceable: Hinman (2012) recommended that interfaces should be ‘glanceable’, thus, indicators and pathways for sustainability should be easily visible at first glance, and not hidden deep within submenus.

- Be subtle: Indicators need to work sympathetically with the user’s tasks and goals that they wish to achieve (Preece et al., 2015), which is unlikely to be finding sustainable garments unless the app is specifically for an ethical/sustainable brand.

- Be functional: It is important to enact the triggers of Fogg (2009) and goal-driven approach (Preece et al., 2015), thus, any additional design elements must add a suitably high-enough element of functionality to the app to make their inclusion justified. In the implementation stage, this can be seen as adding sustainable triggers/facilitators throughout the app as a core feature, rather than an addition to select areas.

- Be symbolic: Such indicators of sustainability should borrow metaphors from the real world to create intuitive links between the intended app use and the symbolism users already understand through society (Yarmosh, 2011). However, Yarmosh (2011) also highlights how such symbolism can lead to the app having a ‘personality’ (playful, minimalist, serious, etc.), that must be in tune with the desired consumer impact.

- Be enjoyable: As Norman (2005), and scientific research (Kurosu & Kashimura, 1995; Tractinsky, 1997) has demonstrated, interfaces that are ‘enjoyable’ and ‘aesthetically pleasing’ are perceived as being of higher functionality. In essence, enhancing both the hedonic and utilitarian experiences crucial for app usability (Parker & Wang, 2016).

Importantly, these design principles must be applied to all aspects of the app, which within a modest m-commerce platform must include (but not limited to):

- Landing page

- Category page

- Search results

- Product information

- Shopping basket

- Checkout page

- Store finder

- Lookbooks

- Company information.

Consequently, it is not a simple case of asking: ‘can I add an element to facilitate/trigger sustainable purchase behaviour in my app’, but instead, one should ask: ‘what can I do on each and every page to help trigger/facilitate sustainable purchase behaviour’. This question is addressed within this chapter.

6. Ideation, prototyping, and testing

In line with the requirements of the design brief, a simple tool was generating – a matrix of design principles to be used as a checkbox on each page type (Figure 7.1). At each stage of design, the following key questions were raised: ‘Are we satisfying each design principle?’ and ‘Are we allowing for both triggers and facilitators to emerge?’ This was found to be a useful and practical item, as it allowed the complex multitude of possibilities to be considered and developed for within a very short space of time.

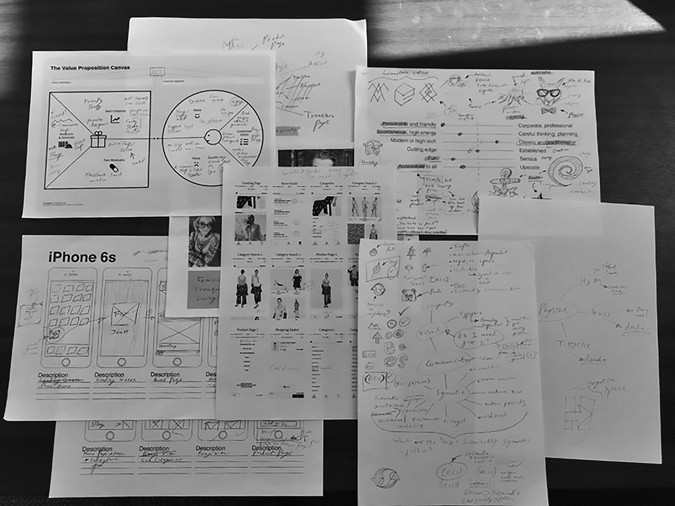

Using Design Thinking, and based upon the summarised background research presented above, a series of concept designs were created to explore the integration of sustainable features within a fashion app (Figure 7.2).

Figure 7.1

Design principle tool

Source: CC BY-NC-SA. (*References for all figure images taken from Fervent-adepte-de-la-mode, 2000; S B, 2004; Herval, 2006a, 2006b; THOR, 2008a, 2008b; Dooley, 2013).

Figure 7.2

Example sketches within the ideation phase

Source: Artwork created by the author, Christopher J. Parker.

After the initial ideation phase, the most promising designs were selected using the criteria of potential desirability, feasibility, and profitability (Figure 7.3). The selected design was taken further into lo-fi prototyping within Adobe InDesign.

Here, the phrase (eco) was added to the menus and text, as well as a leaf icon; see Figure 7.4. These were to work on the principle as triggers and enablers, instantly communicating to the viewer that the products marked are sustainable, or environmental.

Figure 7.3

Prototype fast fashion m-commerce app with sustainable product indicators

Source: Artwork created by the author, Christopher J. Parker.

Figure 7.4 Concept triggers/enablers for sustainable fashion shopping

Source: Concept app design created by the author, Christopher J. Parker.

The word ‘eco’ was chosen for its close association with environmentalism and sustainability in non-professional persons (EFF, 2017; Henninger, 2015), as well as contrasting the branding typeface enough to be differentiated for the standard text within a glance. Similarly, the leaf icon refers to natural iconography within the mind of the user and can be scaled, simplified and modified further due to its potential as negative space. Finally, both the icon and the text not only triggers investigative curiosity and enables identification of products instantly, but can also act as buttons to take the user to an information page, video or website and so forth.

7. Conclusion

The main contribution of this chapter is providing a series of examples on how sustainable behaviour triggers may be integrated into fashion retail apps, with the utilisation of Design Thinking. This chapter has drawn together a deep insight into the gap between sustainable products and the lack of its facilitation in the m-commerce retail ecosystem. The importance of its inclusion within the fast fashion environment has been highlighted, and the need for a more targeted approach to facilitate and enable consumers to engage with sustainable fashion outlined. While the consumer call for such interfaces may currently be in its infancy, it is important to remember the ethos of Steve Jobs (1998), that you must design and market ideas that people do not yet know they desire. Consequently, enacting upon the design principles as suggested within this chapter pave the way for the successful and positive inclusion of sustainable triggers/facilitators within the m-commerce ecosystem. This chapter demonstrates that the issue of sustainability within fast fashion must and can be addressed, and addressed appropriately and powerfully with the m-commerce platform as a facilitating environment for change.

Yarmosh (2011) highlights it is imperative that the ‘personality’ indicated by the app design matches the personality of the brand. Therefore, it is impossible to simply transpose the suggested designs of this chapter to every fashion app and have them work with equal success. It is vital that the design lessons of this chapter is considered by the app design team, and implemented into the design process, possibly as part of an iterative/agile design rollout. Further research is required to take the concepts and initial ideas generated within this chapter, and investigate the degree to which the iconography triggers behaviours and enables identification within a fast fashion setting to allow sustainable products to become integrally valued within an m-commerce platform.

References

Aßländer, M. S., & Curbach, J. (2014). The corporation as citoyen? Towards a new understanding of corporate citizenship. Journal of Business Ethics, 120 (4), 541–554. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-2004-8

ASOS. (2017). ASOS iPhone app. Manchester: Asos.com.

Bédat, M. (2016). Our love of cheap clothing has a hidden cost: It’s time for a fashion revolution. Retrieved 13 December 2016 from www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/04/our-love-of-cheap-clothing-has-a-hidden-cost-it-s-time-the-fashion-industry-changed/

Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. London: Penguin Books.

Bhamra, T., & Lofthouse, V. (2007). Design for sustainability: A practical approach. In R. Cooper (Ed.), Design for social responsibility. Burlington, VT: Gower.

Channel 4. (2017). Undercover: Britain’s cheap clothes: Channel 4 dispatches. Retrieved 17 March 2017 from www.channel4.com/info/press/news/undercover-britains-cheap-clothes-channel-4-dispatches

Charband, Y., & Jafari Navimipour, N. (2016). Online knowledge sharing mechanisms: A systematic review of the state of the art literature and recommendations for future research. Information Systems Frontiers, 18 (6), 1131–1151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796–016–9628-z

Conca, J. (2015). Making climate change fashionable: The garment industry takes on global warming. Retrieved 13 December 2016 from www.forbes.com/sites/jamesconca/2015/12/03/making-climate-change-fashionable-the-garment-industry-takes-on-global-warming/#52ae7b96778a

De Chernatony, L., & McDonald, M. (2003). Creating powerful brands (3rd ed.). Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann.

Delloitte. (2016). There’s no place like phone: Consumer usage patterns in the era of peak smartphone. Retrieved 19 March 2017 from www.deloitte.co.uk/mobileuk/assets/pdf/Deloitte-Mobile-Consumer-2016-There-is-no-place-like-phone.pdf

Dooley, K. (2013). Fashion model. CC BY 2.0. Retrieved 13 May 2017 from https://flic.kr/p/fkdPyz

Dorst, K. (2011). The core of “design thinking” and its application. Design Studies, 32 (6), 521–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2011.07.006

Duffey, K. (1997). Global Mobile Commerce Forum. In Global Mobile Commerce Forum: Inaugural Plenary Conference. Heathrow: Global Mobile Commerce Forum.

EFF. (2017). Organic and eco fashion. Retrieved 11 May 2017 from www.ethicalfashionforum.com/the-issues/organic-eco-fashion

Fervent-adepte-de-la-mode. (2000). Alina, Via Spiga. CC BY 2.0. Retrieved 13 May 2017 from https://flic.kr/p/dZURBj

Fogg, B. J. (2009). A behavior model for persuasive design. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Persuasive Technology (p. 40). Claremont, NY: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/1541948.1541999

GreenApes. (2017). GreenApes iPhone app. Green Apes. GreenApes Srl.

GreenGlamGo. (2011). Green Glam Go! Retrieved 18 March 2017 from www.youtube.com/watch?v=aaygEE3P5Cw

Henninger, C. E. (2015). Traceability the new eco-label in the slow-fashion industry? Consumer perceptions and micro-organisations responses. Sustainability, 7 (12), 6011–6032. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7056011

Henninger, C. E., Alevizou, P. J., & Oates, C. J. (2016). What is sustainable fashion? Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 20 (4), 400–416. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-07–2015–0052

Herval. (2006a). Blondie strikes back. CC BY 2.0. Retrieved 13 May 2017 from https://flic.kr/p/svsnj

Herval. (2006b). Hairy girl. CC BY 2.0. Retrieved 13 May 2017 from https://flic.kr/p/sqw9o

Hinman, R. (2012). The mobile frontier: A guide for designing mobile experience. Brooklyn, NY: Rosenfeld Media.

Hugo Boss. (2017). Hugo Boss iPhone app. Hugo Boss AG.

Jobs, S. (1998, May). Steve Jobs Business Week Interview. Business Week.

Joergens, C. (2006). Ethical fashion: Myth or future trend? Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 10 (3), 360–371. https://doi.org/10.1108/13612020610679321

Kurosu, M., & Kashimura, K. (1995). Apparent usability vs. inherent usability: Experimental analysis on the determinants of the apparent usability. In CHI ’95 Conference Companion on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 292–293). Denver, CO: CHI. https://doi.org/10.1145/223355.223680

Leavy, B. (2010). Design thinking: A new mental model of value innovation. Strategy & Leadership, 38 (3), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1108/10878571011042050

Lejeune, T. (2016). Why we need a sustainable ASOS and how to make that happen. Retrieved 18 March 2017 from www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/tamsin-lejeune/why-we-need-a-sustainable_1_b_12734164.html

Mercer, J. (2014). E-Commerce – UK – July. London: Mintel.

Mittelstaedt, J. D., Shultz, C. J., Kilbourne, W. E., & Peterson, M. (2014). Sustainability as megatrend: Two schools of macromarketing thought. Journal of Macromarketing, 34 (3), 253–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276146713520551

Netter, S. (2017). User satisfaction & dissatisfaction in the app sharing economy. In C. E. Henninger, P. J. Alevizou, H. Goworek, & D. Ryding (Eds.), Sustainability in fashion: A cradle to upcycle approach. London: Palgrave.

The Nielsen Company. (2014). The digital consumer. Oxford: Nielsen.

Norman, D. A. (2005). Emotional design: Why we love (or hate) everyday things (Vol. Paperback). Cambridge, MA: Basic Books.

Parker, C. J., & Wang, H. (2016). Examining hedonic and utilitarian motivations for m-commerce fashion retail app engagement. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 20 (4), 487–506. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-02–2016–0015

Parveen, S. (2014). Rana Plaza factory collapse survivors struggle one year on. Retrieved 13 December 2016 from www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-27107860

Poq Studio. (2016). People tree. Poq Studio Ltd.

Preece, J., Rogers, Y., & Sharpe, H. (2015). Interaction design: Beyond human-computer interaction (4th ed.). Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

S B. (2004). F1020020. CC BY 2.0. Retrieved 13 May 2017 from https://flic.kr/p/3tzmu

Shen, B., Zheng, J.-H., Chow, P.-S., & Chow, K.-Y. (2014). Perception of fashion sustainability in online community. Journal of the Textile Institute, 105 (9), 971–979. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405000.2013.866334

Siegle, L. (2014). How can we get young people to say no to fast fashion? Retrieved 13 December 2016 from www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/apr/20/should-we-say-no-to-fast-fashion

Statista. (2017). Share of mobile phone users that use a smartphone in the United Kingdom from 2010 to 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2017 from www.statista.com/statistics/257051/smartphone-user-penetration-in-the-uk/

THOR. (2008a). ScottTEST (47). CC BY 2.0. Retrieved 13 May 2017 from https://flic.kr/p/5doscy

THOR. (2008b). ScottTEST (53). CC BY 2.0. Retrieved 13 May 2017 from https://flic.kr/p/5dj8rc

Tractinsky, N. (1997). Aesthetics and apparent usability: Empirically assessing cultural and methodological issues. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems: CHI ’97 (pp. 115–122). New York: ACM Press. https://doi.org/10.1145/258549.258626

WebHouse. (2017). Better World iPhone app. WebHouse.

Yarmosh, K. (2011). App savvy (B. Jepson, Ed., 2nd ed.). Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly Media.

Zimmerman, K. (2016). What to do with a millennial employee that’s bored at work. Retrieved 19 March 2017 from www.forbes.com/sites/kaytiezimmerman/2016/11/13/what-to-do-with-a-millennial-employee-that-is-bored-at-work/#3d07fc5e3014