18

From sustainable sourcing to sustainable consumption

The case of DBL Group in Bangladesh

Introduction

The industry understands that it cannot afford another accident such as Rana Plaza. Concerns among consumers and the international community have never been so high. Their actions in the form of protests, rallies, demonstrations as well as productive alliances, have expressed and pointed out the urgent need to enforce laws and regulations and to demonstrate more responsible behaviour by all actors engaged in the supply chain.

(Farooq Sobhan, Chairman of the Bangladesh Enterprise Institute)

Since Rana Plaza, numerous initiatives took place in order to address the structural causes of the tragedy but also to come out with viable solutions for the garment sector of Bangladesh to grow sustainably. Several institutional mechanisms have been put in place to address safety and occupational health in the workplace, such as the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh (ACCORD) in May 2013 and the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety (ALLIANCE) in July 2013, which have been contributing to the institutional environment’s change of the garment industry of Bangladesh. The new institutional environment is promoting more responsible and sustainable business behaviours as summarized by Gifford and Ansett (2014): “notable changes already happened”. However challenges persist which need to be addressed as soon as possible. In fact despite the pressure exercised by the new initiatives, which oblige signatory brands to officially disclose the list of their providers, it does not require providers to detail the second or third tiers of suppliers. Consequently, as the linkages between a specific brand and its suppliers are difficult to track, it is quite hard to acknowledge the origin of a specific garment product.

At the 2016 Conference on Sustainable Sourcing in the Garment Sector (SSGS),1 several mechanisms were discussed to enhance the mutual responsibility of all stakeholders along the supply chain: transparent buying and purchasing practices, industrial development support, sharing information on timely forecasting and production processes and applying fair price and open costing. However, the main research findings of Anner (2016) on the impact of sourcing is that 2016 has to be remembered as the year when the retailers put the ‘big squeeze’ on the suppliers over profit margins, delivery deadlines (lead times) and contributed to the deterioration of working conditions among the top 20 garment exporters to the US. This shows how retailers prefer keeping competitive pricing at the consumers’ end and charging the costs of compliance to the local suppliers. The reasoning behind the retailers’ logics is that consumers are not willing to pay a higher price for garments’ products, even if produced more responsibly. Evidently, the incremental price for responsible clothing would be quite marginal and almost imperceptible but the risk to take a front running position is too high as the market, characterized by the fast fashion model, is not yet ready for that.

A lot of research has shown the contradictory behaviour of consumers vis-à-vis responsible consumption. Jackson (2005), in his review on consumers’ behaviours, argues that it is not easy to explain what motivates consumers to behave unsustainably, as they are not free to choose what to consume as the current system persuades them to buy what is available in the market. Specifically, economic constraints, institutional barriers or inequality of access probably influence the way consumers behave. Furthermore, consumers do not usually follow a rational choice. They are driven by different motivations, induced by set of values, beliefs and social norms which influence their actions. As a consequence the gap between values, motivations and actions persists (Balderjahn, 2013; Carrington, Neville, & Whitwell, 2010; Vermeir & Verbeke, 2006).

Taking into account the above considerations, one way to address consumer choice is by providing products which already incorporate the sustainable elements. The implication is to look back at the way the product is locally produced and brought to the market. With these premises, this study aims at backing the work on Eco-friendly and Fair: Fast Fashion and Consumer Behaviour by understanding the strategic approach taken by a local garment manufacturer in Bangladesh to contribute to sustainable fashion. The study is qualitative in nature based on a case study design approach as it analyzes one specific local company operating in the garment sector of Bangladesh which is striving to integrate sustainability practices within its business operations, in order to manufacture sustainable products.

1. The garment sector of Bangladesh: the strive for sustainable growth

The international attention on the garment sector of Bangladesh can be explained by the relevance this sector has gained within the overall fast fashion industry. The garment industry accounts for over 80% of export revenues of Bangladesh and it represents the second largest world export country, after China. It grew exponentially so that it now counts on more than 5,000 factories, employing approximately four million people, of which more than 80% are women. It became the leading sourcing destination for the EU and US, because of its high competitiveness due to its low production costs, as a result of low labour costs and high productivity.

At the same time, due to the dynamics of the retail market, buyers feel the pressure to keep the prices as low as possible to retain competitive advantages. The price pressure forces local manufacturers to invest in human resources and new technology to boost productivity and face competition. They also couple the increased productivity with improved labour conditions, safety and environmentally sustainable practices. But to keep up with the increasing demand for higher compliance standards, they need investments which they could obtain by increasing operational costs or by gathering extra capital to invest. Most importantly, they need the guarantee from the buyers of continuous orders at feasible prices.

On the other hand, buyers are forced to act fast, selling short cycle collections, forecasting their sales in short planning cycles, due to the increasing demand of consumers. This process is feeding the fast and low-cost fashion industry which is today represented by a growing number of low-cost, basic and mid-cost fast fashion chains. The challenge remains of determining a fair price which could account for higher costs of production to comply with compliance and corporate social responsibility (CSR) standards at sourcing level. In the next section, the sustainable framework of reference is introduced, to guide the case study analysis.

2. The sustainability framework of analysis

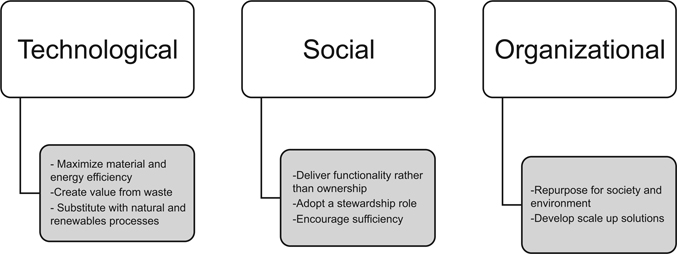

The neoclassical economic model which pursues profit maximization is inadequate to address effectively the social and environmental challenges the world faces today (Stubbs & Cocklin, 2008; Mackey & Sisodia, 2013). For that, a new business model which takes into account the impacts, by internalizing the related costs, on society and environment and stakeholders’ needs is required. The research of Bocken, Short, Rana, and Evans (2014) helps to identify the most suitable sustainable business models, which can be used as a reference for understanding company’s approach to sustainability. They introduce eight different sustainable business archetypes to emphasize how, by integrating sustainability and innovation approaches into business’ purpose and process, it creates competitive sustainability of the firm; it reduces cost of production by increasing efficiency; and enhances stakeholder’s engagement and customer loyalty. The eight archetypes are categorized and regrouped into three different categories: the technological one which focuses on how to improve efficiency and value creation through technical innovation (i.e. reduction of water and energy consumption; creating value from waste; substitution with renewable and ‘organic processes); the social, which looks at how innovative products and services can influence consumers’ behaviours; and the organizational, which supports the idea of aligning the business purpose towards a more structured contribution to society and environment by, for instance, changing the fiduciary responsibility of the company and/or scaling up the business. In brief, the sustainable business models of Bocken et al. (2014) can be represented as follows:

Thus, when companies are able to redesign their business model following the approach of business model innovation, they will be able to integrate sustainability into their businesses (Bocken et al., 2014). Ideally various archetypes should be employed to build a more systemic and holistic approach to sustainability, thus mitigating the risks of creating undesirable impacts on employment by only applying productivity and efficiency improvements (Herring & Sorrell, 2009).

3. The methodological approach

The research is qualitative in nature and it uses the case study approach of one individual unit of analysis. The identification of just one case study is justified by the interest of better understanding the phenomena of sustainability by studying in depth a single company within a specific context (Stake, 1998). The specific company was selected following various methodological steps. Initially, local business leaders, who are recognized to be socially responsible in the ready-made garment sector of Bangladesh, were identified by applying a non-probability sampling method while conducting semi-structured interviews with 25 experts. In addition document analysis helped with checking their commitment to standards and certifications. This process delivered a list of 15 companies leading in the field of ‘CSR’. These companies have been approached separately to corroborate their interest and concrete application of sustainability practices, by fulfilling a pre-test on CSR. Only nine leaders committed to filling up the test and agreed to open the factory’s doors for an observation visit to corroborate if, what has been described in the pre-test actually corresponds to concrete actions and practices at factory’s level. Once the nine leaders were interviewed with in-depth interviews, they were approached to check their interest to participate in the current study. The result of the inquiry was the selection of DBL Group as the specific unit of analysis.

The research takes as a reference the sustainability reports from DBL Group for the last 3 years (2013, 2014–2015, 2016) complemented by data collected by the author during the company visit and by the transcripts of the interview taken with the managing director of DBL Group. The content analysis of the reports and primary data helps in identifying patterns of sustainability practices in accordance with one or various categories and archetypes of Bocken’s sustainability business models. This methodological approach contributes to a more thorough description of the sustainability journey of DBL Group and highlights what it might pursue to ensure an effective integration of sustainability within its business model.

4. DBL and its sustainability journey

DBL Group was established in 1991, as a family-owned company. It is one of the largest composite knit garments and textiles’ manufacturers and exporters in Bangladesh. DBL Group is a diversified conglomerate of 14 companies, with a strong backward linkage in spinning, knitting, dyeing, all-over printing, screen printing, garments manufacturing, garments accessories manufacturing, washing, packaging, ceramic tiles, telecommunications and lately dredging and pharmaceuticals. The headquarter is in Dhaka and its factories are in Gazipur. Within the garment sector, DBL produces several products such as yarns, fabrics, casual knitwear and fashionable wear. Its vision is to sustain and grow as a diversified global conglomerate, in respect of the values of integrity, passion, adaptability, care and excellence. In 2016 the DBL group employed more than 24,500 people with an annual turnover of approximately $360 million (DBL, 2016). In 2015–2016 a total of 73,972,211 pieces had been exported with an annual increase of export of 29.7% (DBL, 2014–2015).

The major buyers are H&M, Walmart, George, Esprit, PUMA, G-Star Raw, Decathlon, Next, Tom Taylor, Gerry Weber, MQ, M&S, Gymboree and LIDL. DBL is a family-owned business which follows strict regulations on corporate governance as set by the International Finance Corporation (IFC). Recently the Matin Spinning Mills has been publicly listed under the Bangladesh Securities and Exchange Commission and is available for public trading. DBL is also a signatory to the UN Global Compact (UNGC) and follows Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) reporting standards. Its policies adhere to various standards like the conventions of ILO, the UN on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, against child labour and all discriminations against women. To achieve that, it signed various Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs) with different organizations such as UNICEF, CARE Bangladesh and Marie Stopes. It also follows the guidelines and standards of BSCI, WRAP, SA8000, ETI, ISO 9001, ISO 14001, SAI (150.1–150.8), OHSAS 18001, IFC Environmental and Social performance standards. Due to its strong backward linkage, DBL ensures a better control on the sourcing practices of the raw material, especially cotton. Its participation in the International Cotton Initiative (ICA) contributes to address the social and environmental challenges faced by local farmers in producing cotton. Along the manufacturing process, it uses advanced technology and machinery to reduce the use of hazardous materials, water consumption during dying processes, and it tests the quality of garments according to the CAS, CAD and CAM systems.

Labour conditions are at the centre of DBL’s interest; its motto is ‘Crafting Happiness’ on the belief that “the productivity and profitability of a company relies mainly on the workers and the way they feel acquainted and loyal to the company” (MD DBL Group). Several programmes have been set up with the help of various organizations (CARE, Phulki, GIZ, WFP, UNICEF, etc.), to address issues concerning sexual and reproductive health, safety and occupational health, management relationships and leadership training and enhancement of living conditions (i.e. the Bandhan Fair Price Shop). In terms of relationships with stakeholders, DBL has constituted different teams to engage with them. The merchandising team has direct and bilateral contact with the customers, in this specific case the buyers. The investors’ relations team looks at the interests of the major DBL investors, namely financial institutions and institutional donors. Then the compliance team ensures that DBL complies with all agreements with respect to protecting the environment and the workforce.

Particular attention is given to the employees and surrounding communities. Various activities have been implemented to enhance the communication and engagement with the employees and local communities’ leaders. Grievance mechanisms as well as employees’ feedbacks on process improvements have been established to enhance transparency and accountability. With local communities, DBL created welfare committees to identify local priorities and needs and strategic actions on the most appropriate ways to meet the expectations of society. Examples are physical extension of Hatimara College, women’s empowerment programmes, health development initiatives and mini-fire brigades. The company approaches sustainability by integrating five components within the core values of the company: people, process, product, community and environment. This process has been guided since 2013 by completing the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) G4 and seeking external assistance. For each component, DBL has defined specific objectives and activities to facilitate the integration of sustainability within its company.

5. Comparison of DBL with the sustainable business models archetypes

In order to create an overview of the completeness and depth of the sustainability approach taken by DBL, this section maps the sustainability activities of DBL against a norm. Taking as a reference the framework of sustainable business model of Bocken et al. (2014), DBL sustainability practices can be categorized according to various archetypes. In Table 18.1, the first column presents the eight archetypes included in the model of Bocken et al. (2014). The second column contains the definition of archetypes as defined by Bocken et al. (2014). The third column maps all relevant activities of DBL that fits with that specific archetype. And the last column presents the additional consideration that are not yet implemented by DBL, but would fit with that archetype.

Table 18.1 Review of DBL sustainability practices with respect to archetypes for sustainable business models

| Technological | Bocken’s definition | DBL practices | Further considerations |

|

|

|||

| Efficiency: Maximize materials and energy efficiency | Enhancing efficient use of resources, and reducing waste and emissions through products and processes redesign |

|

Social impact on employment rates |

| Waste: Create value from waste | Making use of waste as an input for other products and processes (closed loop and cradle to cradle) |

|

Focus on initial phase of manufacturing |

| Substitute with natural and renewables processes | Replacing resources in depletion or hazardous with renewables resources and natural processes (blue economy; biomimicry) |

|

|

| Social | |||

| Deliver functionality rather than ownership | Shifting business model from manufactured product to combination of services and products; it delivers pay-for-use service instead of ownership of products |

|

|

| Adopt a stewardship role | Engaging with all stakeholders in the supply chain to promote and contribute to sustainability |

|

|

| Encourage sufficiency | Adopting practices which reduce consumption and production |

|

Non-direct contact with end consumers |

| Organizational | |||

| Repurpose for society and environment | Identifying as main business objective the contribution to society and environment (social entrepreneurship; social businesses; not-for-profit) |

|

Family-owned business |

| Develop scale-up solutions | Replicating and expanding the sustainable business model |

|

Information not available outside the garment sector |

6. Discussion

This chapter provides an overview of what is possible on the other side of the spectrum compared to Rana Plaza and other factories that base their business model on low-wage, poor quality and often unsafe and environmentally degraded working conditions. In doing so, it illustrates that it is a matter of choice whether unsustainable practices and ready-made garment from Bangladesh are linked to each other. This chapter proves that if the leaders of a company focus on strong ties with stakeholders and a different business model, it is possible to produce good quality garment for a reasonable price even in a country like Bangladesh.

The comparison to the archetypes’ categorization of the sustainability business models of Bocken et al. (2014), identifies DBL’s relevant practices in applying sustainability. From Table 18.1, it is evident that DBL puts much more emphasis on the technological component, understanding the need to address multiple challenges derived by the inefficient use of resources and the impact it can generate on the environment and society. So far, DBL is applying various technological solutions to reduce the company’s water and energy footprint. Recently, it also focused on reducing waste by increasing the use of recycled and reusable garment products in the manufacturing process (DBL, 2016).

On the social component category, while DBL is actively engaged in upstream stakeholders’ relationship, it lacks access to the downstream of the supply chain. This is due to its disconnection with the end consumers as the buyers and retailers are the ones who define this relationship. As mentioned by the managing director of DBL Group, consumers “have a role to influence our behaviours but quite distant and indirect through the brands.” The absence of direct relationship also affects its inaction towards the promotion of different practices of production and consumption which is still highly dependent on the fast fashion business model which pushes for increasing production at squeezed prices.

Lastly, on the organizational component, DBL is a family-owned company which is non-publicly listed with exception of one of its unit, and which obtains its financial sources from external investors, mainly financial institutions. For this reason the company has the potential to strengthen its focus on societal and environmental purposes rather than to maximize profits for its shareholders. For its contribution to society, DBL initiated the Matin-Jinnat Foundation in 2006. The foundation is a charitable trust named after the parents of the founding directors of DBL Group. The trust has been formed to look after the welfare of the poor and needy following Islamic principles. Service to the poor is provided in the form of donations to schools, clinics, orphanages and local communities. The foundation runs with 5% of the profits generated by DBL Group.

In general, as also pointed out by Bocken et al. (2014), the categorization undermines the social aspect of sustainability in favour of environmental innovation thus dismissing the role the company has in empowering workers as well as local communities in contributing to sustainability. In the case of DBL, the focus on people is quite strong in terms of enhancing their active participation in the company, as mentors, within the idea club and DBL quality control cycles, but also as leaders, with special emphasis on women (Women in Factories Initiatives; Female Supervisors Leadership Programme; Women Health Initiative Programme and Financial Literacy Programme). Nevertheless, the social impacts of such practices is not adequately evaluated, thus refraining from adopting more innovative approaches which could also spread and internalize the concept and practices of sustainability at local level.

7. Conclusions

In response to the call for submissions on Eco-friendly and Fair: Fast Fashion and Consumer Behaviour, this chapter aims at understanding the strategic approach taken by DBL Group in Bangladesh to contribute to sustainable fashion. It is concluded that the sustainability practices of DBL Group focus primarily on the technological category of the Bocken’s sustainable business models, with emphasis on technology and innovation to curb the negative impact of inefficient use of resources, waste and emissions on the environment and society. Despite its efforts in contributing to society with various philanthropic programmes through the DBL Foundation, the social benefits generated are not adequately reported and internalized in the current business model.

In order to strengthen their sustainable business model, local manufacturers are highly dependent on buyer compliance requirements. They still have limited power of negotiation to promote more advanced forms of sustainable business models which could influence consumer behaviour. For that, a closed-loop approach applied to the supply chain with a more participative and collaborative interaction of all stakeholders could probably reduce the distance between downstream and upstream of the supply chain.

Further research should address the challenges of identifying mechanisms to create a direct connection between the local manufacturers and the end consumers with the aim of creating more transparency along the supply chain to track the product life cycle, thus its costing which could facilitate the determination and application of a fairer price of the end garment product.

Note

1 The conference was organized by the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands-EKN and BGMEA in Dhaka on 29 September 2016. All information on the conference can be retrieved at http://ssgs-bd.com/.

References

Anner, M. (2016). Toward fair pricing? Sourcing dynamics in the apparel industry: Sustainable Models for the Apparel Industry. Bangladesh Development Conference 2016, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, 24 September 2016.

Balderjahn, I. (2013). Nachhaltiges Management und Konsumverhalten. Konstanz und München: UVK Verlagsgesellschaft mbH.

BGMEA. (2016, February–March). The apparel sector. BGMEA Quarterly Magazine. Retrieved from www.bgmea.com.bd/home/newsletterlist/

Bocken, N.M.P., Short, S. W., Rana, P., & Evans, S. (2014). A literature and practice review to develop sustainable business model archetypes. Journal of Cleaner Production, 65, 42–56.

Carrington, M. J., Neville, B. A., & Whitwell, G. J. (2010). Why ethical consumers don’t walk their talk: Towards a framework for understanding the gap between the ethical purchase intentions and actual buying behaviour of ethically minded consumers. Journal of Business Ethics, 97, 139–158.

DBL. (2013). Sustainability report. Retrieved from www.dbl-group.com/data/frontImages/DBL_Sustainability_Report_2013.pdf

DBL. (2014–2015). Sustainability report. Retrieved from www.dbl-group.com/data/frontImages/DBL_Sustainability_Report_2014-2015.pdf_

DBL. (2016). Sustainability report. Retrieved from www.dbl-group.com/data/frontImages/DBL_Sustainability_Report-2016.pdf

Giffor d, J., & Ansett, S. (2014, 2 April). 10 things that have changed since the Bangladesh factory collapse. Guardian.com.

Herring, H., & Sorrell, S. (2009). Energy efficiency and sustainable consumption: The rebound effect. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Jackson, T. (2005, January). Motivating sustainable consumption: A review of evidence on consumer behaviour and behavioural change: A report to the SDRN. Retrieved from www.sd-research.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/Motivating%20Sustainable%20Consumption1_0.pdf

Mackey, J., & Sisodia, R. (2013, 14 January). Conscious capitalism is not an oxymoron. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2013/01/cultivating-a-higher-conscious

Stake, R. (1998). Case studies. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), Strategies of qualitative inquiry. London: Sage.

Stubbs, W., & Cocklin, C. (2008). Conceptualizing a sustainability business model. Organization & Environment, 21 (2), 103–127.

Vermeir, I., & Verbeke, W. (2006). Sustainable food consumption: Exploring the consumer attitude-behavioural intention gap. Journal of Agriculture and Environmental Ethics, 19, 169–194.