Chapter 13

Supply Chain Management and Cloud Security

We cannot enter into alliance with neighboring princes until we are acquainted with their designs.

—The Art of War, Sun Tzu

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

Understand the essential concepts of supply chain management.

Make a presentation concerning the application of risk management and risk assessment policies to supply chains.

Present an overview of cloud computing concepts.

List and define the principal cloud services.

List and define the cloud deployment models.

Discuss key management concerns related to cloud service security.

Present an overview of supply chain best practices.

Discuss the differences between document management and records management.

Present an overview of the considerations involved in protecting sensitive physical information.

Present an overview of information management best practices.

This chapter is concerned with security services related to the use of external providers/vendors of products and services. It begins with an introduction to the concept of supply chain and supply chain management issues. Next, it examines the application of risk management and risk assessment policies and procedures to the security concerns related to supply chain management.

The remainder of the chapter looks at significant type of external provision, namely cloud computing services, and deals with the issues peculiar to this topic. Section 13.3 introduces basic concepts of cloud computing, and Section 13.4 discusses cloud security from the point of view of the cloud service customer.

13.1 Supply Chain Management Concepts

As enterprises pursue outsourcing strategies and their supply and delivery systems become increasingly global, the visualizing, tracking, and management of supply chains becomes increasingly complex. A significant reliance on supply chains also introduces increased risk into the organization. This section introduces the basic concepts of the supply chain and supply chain management and sets the stage for an examination of security aspects of supply chain management in Section 13.2.

The Supply Chain

Traditionally, a supply chain was defined as the network of all the individuals, organizations, resources, activities, and technology involved in the creation and sale of a product, from the delivery of source materials from the supplier to the manufacturer, through to its eventual delivery to the end user. In this traditional use, the term applies to the entire chain of production and use of physical products. The chain can link a number of entities, beginning with raw materials suppliers, through manufacturers, wholesalers, retailers, and consumers.

More recently the term supply chain has been used in connection with information and communications technology (ICT). National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) SP 800-161, Supply Chain Risk Management Practices for Federal Information Systems and Organizations, defines the term ICT supply chain as follows:

information and communications technology (ICT)

Refers to the collection of devices, networking components, applications, and systems that together allow people and organizations to interact in the digital world. ICT is sometimes used synonymously with IT; however, ICT represents a broader, more comprehensive list of all components related to computer and digital technologies than IT.

Linked set of resources and processes between acquirers, integrators, and suppliers that begins with the design of ICT products and services and extends through development, sourcing, manufacturing, handling, and delivery of ICT products and services to the acquirer. Note: An ICT supply chain can include vendors, manufacturing facilities, logistics providers, distribution centers, distributors, wholesalers, and other organizations involved in the design and development, manufacturing, processing, handling, and delivery of the products, or service providers involved in the operation, management, and delivery of the services.

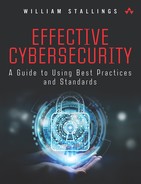

Figure 13.1 is a simplified view of the flows in an ICT supply chain.

An enterprise procures the following from external sources:

Services: Examples include cloud computing services, data center services, network services, and external auditing services.

Software/data: Examples include operating system and application software and databases of information, such as threat information.

Hardware/products: Examples include computer and networking equipment.

The procured items are often for internal use but can be packaged, integrated, or otherwise prepared for sale to external customers.

Figure 13.1 indicates three types of flows associated with a supply chain:

Product/service flow: A key requirement is a smooth flow of an item from the provider to the enterprise and then on to the internal user or external customer. The quicker the flow, the better it is for the enterprise, as it minimizes the cash cycle.

Information flow: Information flow comprises the request for quotation, purchase order, monthly schedules, engineering change requests, quality complaints, and reports on supplier performance from the customer side to the supplier. From the producer’s side to the consumer’s side, the information flow consists of the presentation of the company, offer, confirmation of purchase order, reports on action taken on deviation, dispatch details, report on inventory, invoices, and so on.

Money flow: On the basis of the invoice raised by the producer, the clients examine the order for correctness. If the claims are correct, money flows from the clients to the respective producer. Flow of money is also observed from the producer side to the clients in the form of debit notes.

Supply Chain Management

Supply chain management (SCM) is the active management of supply chain activities to maximize customer value and achieve a sustainable competitive advantage. It represents a planned initiative by the enterprises to develop and run supply chains in the most effective and efficient ways possible. Supply chain activities cover everything from product development, sourcing, production, and logistics to the information systems needed to coordinate these activities.

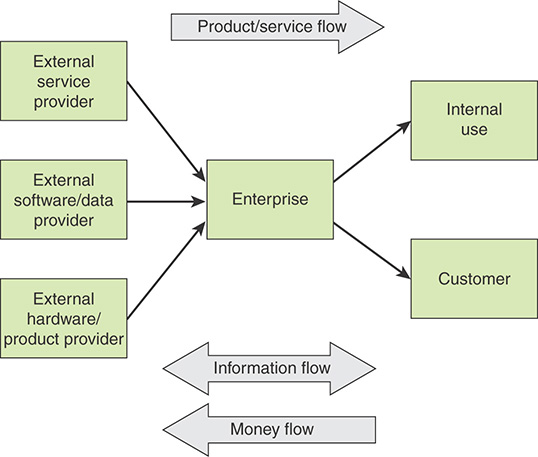

Figure 13.2 illustrates a typical sequence of elements involved in supply chain management.

The elements of supply chain management include the following:

Demand management: This function recognizes all demands for goods and services to support the marketplace. It involves prioritizing demand when supply is lacking. Proper demand management facilitates the planning and use of resources for profitable business results.

Supplier qualification: This function provides an appropriate level of confidence that suppliers, vendors, and contractors are able to supply consistent quality of materials, components, and services in compliance with customer and regulatory requirements. An integrated supplier qualification process should also identify and mitigate the associated risks of materials, components, and services.

Supplier negotiation: In this process of formal communication, two or more people come together to seek mutual agreement on an issue or issues. Negotiation is particularly appropriate when issues besides price are important for the buyer or when competitive bidding does not satisfy the buyer’s requirements on those issues.

Sourcing, procurement, and contract management: Sourcing refers to the selection of a supplier or suppliers. Procurement is the formal process of purchasing goods or services. Contract management is a strategic management discipline employed by both buyers and sellers whose objectives are to manage customer and supplier expectations and relationships, control risk and cost, and contribute to organizational profitability/success. For successful service contract administration, the buyer needs to have a realistic degree of control over the supplier’s performance. Crucial to success in this area is the timely availability of accurate data, including the contractor’s plan of performance and the contractor’s actual progress.

Logistics and inventory control: In this context, logistics refers to the process of strategically managing the procurement, movement, and storage of materials, parts, and finished inventory (and the related information flows) through the organization and its marketing channels. Inventory control is the tracking and accounting of procured items.

Invoice, reconciliation, and payment: This is the process of paying for goods and services.

Supplier performance monitoring: This function includes the methods and techniques for collecting information to be used to measure, rate, or rank supplier performance on a continuous basis. Performance refers to the ability of the supplier to meet stated contractual commitments and enterprise objectives.

13.2 Supply Chain Risk Management

Supply chain risk management (SCRM) is the coordinated efforts of an organization to help identify, monitor, detect, and mitigate threats to supply chain continuity and profitability. SCRM, in essence, applies the techniques of risk assessment, as discussed in Chapter 3, “Information Risk Assessment,” to the supply chain. All the techniques discussed in that chapter are relevant to this discussion of SCRM.

NIST has published two useful documents related to SCRM. SP 800-161 describes the SCRM process, provides a detailed description of supply chain threats and vulnerabilities, and defines a set of security controls for SCRM. NISTIR 7622, Notional Supply Chain Risk Management Practices for Federal Information Systems, focuses on best practices for SCRM. NIST also maintains a website devoted to SCRM that includes a number of industry papers on the subject.

Cyber Supply Chain Risk Management https://csrc.nist.gov/projects/supply-chain-risk-management/

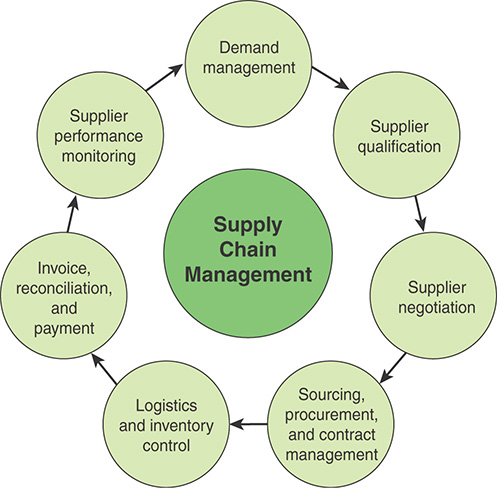

Figure 13.3, from SP 800-161, illustrates the risk assessment process applied to the supply chain (compare Figure 13.1). Like any other form of risk assessment, SCRM risk assessment begins with an analysis of threats and vulnerabilities. As shown in Figure 13.3, threats come from either an adversarial source that intends deliberate harm or from a non-adversarial source, which is an unintentional threat. Vulnerabilities in the supply chain can be external to the organization or internal.

Once the threats and vulnerabilities are determined, it is possible to estimate the likelihood of a threat being able to exploit a vulnerability to produce harm. Risk assessment then involves determining the impact of the occurrence of various threat events.

Supply chain risk assessment is a specific example of the risk assessment done by an organization and is part of the risk management process depicted in Figures 3.2 and 3.3.

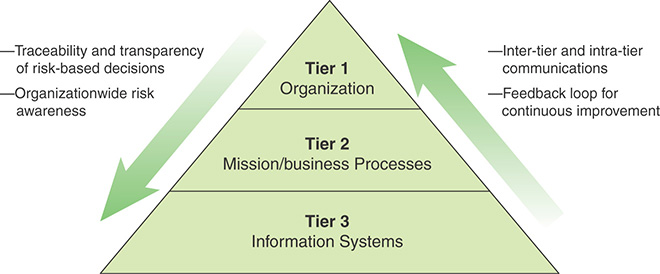

SP 800-161 makes use of a risk management model defined in SP 600-39, Managing Information Security Risk, shown in Figure 13.4. The model consists of three tiers:

Tier 1: This tier is engaged in the development of the overall ICT SCRM strategy, determination of organization-level ICT SCRM risks, and setting of the organization-wide ICT SCRM policies to guide the organization’s activities in establishing and maintaining organizationwide ICT SCRM capability.

Tier 2: This tier is engaged in prioritizing the organization’s mission and business functions, conducting mission/business-level risk assessment, implementing Tier 1 strategy and guidance to establish an overarching organizational capability to manage ICT supply chain risks, and guiding organizationwide ICT acquisitions and their corresponding system development life cycles (SDLCs).

Tier 3: This tier is involved in specific ICT SCRM activities applied to individual information systems and information technology acquisitions, including integration of ICT SCRM into these systems’ SDLCs.

FIGURE 13.4 Multi-tiered Organizationwide Risk Management

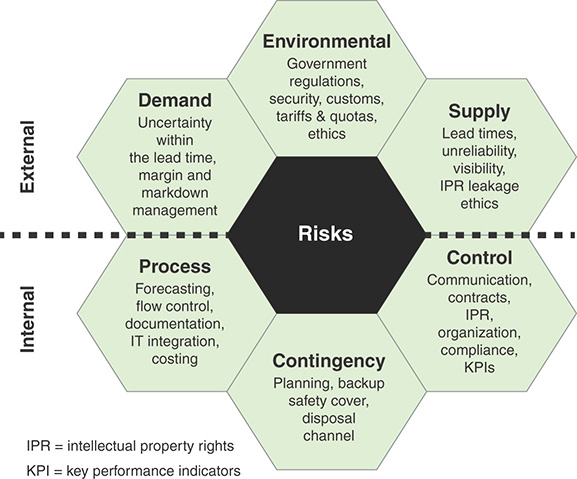

Richard Wilding’s blog post “Classification of the Sources of Supply Chain Risk and Vulnerability” [WILD13] provides a useful perspective on categorizing supply chain risk areas. In general terms, supply chain risks may be either external or internal, as illustrated in Figure 13.5.

intellectual property rights (IPR)

Rights to the body of knowledge, ideas, or concepts produced by an entity that are claimed by that entity to be original and of copyright-type quality.

key performance indicators (KPIs)

Quantifiable measurements, agreed to beforehand, that reflect the critical success factors of an organization.

The external risks are as follows:

Demand: Refers to disturbances to the flow of product, information, or cash from within the supply chain between the organization and its market. For example, disruptions in the cash resource within the supply chain needed to pay the organization can have a major impact on the operating capability of organizations.

Supply: The upstream equivalent of demand risk; it relates to potential or actual disturbances to the flow of product or information from within the supply chain between the organization and its suppliers. In a similar way to demand risk, the disruption of key resources coming into the organization can have a significant impact on the organization’s ability to perform

Environmental: The risk associated with external and, from the firm’s perspective, uncontrollable events. The risks can impact the firm directly or through the firm’s suppliers and customers. Environmental risk is broader than just natural events like earthquakes or storms. It also includes, for example, changes created by governing bodies such as changes in legislation or customs procedures, as well as changes in the competitive climate.

The internal risks are as follows:

Processes: The sequences of value-adding and managerial activities undertaken by the firm. Process risk relates to disruptions to key business processes that enable the organization to operate. Some processes are key to maintaining the organization’s competitive advantage, while others can underpin the organization’s activities.

Controls: The rules, systems, and procedures that govern how an organization exerts control over processes and resources. In terms of the supply chain, controls may relate to order quantities, batch sizes, safety stock policies, and so on, plus the policies and procedures that govern asset and transportation management. Control risk is therefore the risk arising from the application or misapplication of these rules.

Contingency: The existence of a prepared plan and the identification of resources that are mobilized in the event of a risk being identified. Contingency plans may encompass inventory, capacity, dual sourcing, distribution and logistics alternatives, and backup arrangements.

Supply Chain Threats

Table 13.1, from SP 800-161, provides examples of threat considerations and different methods that can be used to characterize ICT supply chain threats at different tiers. These considerations provide an organized way of approaching the threat analysis that is part of risk assessment.

TABLE 13.1 Supply Chain Threat Considerations

Tier |

Threat Consideration |

Methods |

|---|---|---|

Tier 1 |

|

|

Tier 2 |

|

|

Tier 3 |

|

|

As indicated in Figure 13.3, threats are categorized as adversarial or non-adversarial. It is very useful for an organization to have a reliable list of the types of events in each category in order to ensure that all threats are considered in the threat analysis. Table 13.2, from SP 800-161, lists possible adversarial threat events, broken down into seven distinct areas. As shown, the task of threat analysis is formidable.

exfiltration

A malware process that automates the sending of harvested victim data, such as login credentials and cardholder information, back to an attacker-controlled server.

TABLE 13.2 Adversarial Supply Chain Threat Events

Event Category |

Threat Event |

|---|---|

Perform reconnaissance and gather information |

|

Craft or create attack tools |

|

Deliver/insert/install malicious capabilities |

|

Exploit and compromise |

|

Conduct an attack (that is, direct/coordinate attack tools or activities) |

|

Achieve results (that is, cause adverse impacts, obtain information) |

|

Maintain a presence or set of capabilities |

|

In the category of non-adversarial threat events, SP 800-161 lists the following:

An authorized user erroneously contaminates a device, an information system, or a network by placing on it or sending to it information of a classification/sensitivity that it has not been authorized to handle. The information is exposed to access by unauthorized individuals, and as a result, the device, system, or network is unavailable while the spill is investigated and mitigated.

An authorized privileged user inadvertently exposes critical/sensitive information.

A privileged user or administrator erroneously assigns a user exceptional privileges or sets privilege requirements on a resource too low.

Processing performance is degraded due to resource depletion.

Vulnerabilities are introduced into commonly used software products.

Multiple disk errors may occur due to aging of a set of devices all acquired at the same time, from the same supplier.

Supply Chain Vulnerabilities

As with threats, SP 800-163 provides guidance on tier-based analysis of supply chain vulnerabilities. Table 13.3 provides a systematic way of working down from tier 1 through tier 3 to consider all vulnerabilities.

TABLE 13.3 Supply Chain Vulnerability Considerations

Tier |

Vulnerability Consideration |

Methods |

|---|---|---|

Tier 1 |

|

|

Tier 2 |

|

|

Tier 3 |

|

|

For example, in tier 1, a type of vulnerability is a deficiency or weakness in organizational governance structures or processes, such as a lack of an ICT SCRM plan. Ways to mitigate this vulnerability include providing guidance on how to consider dependencies on external organizations as vulnerabilities and seeking out alternative sources of new technology, including building in-house.

An example of a vulnerability at tier 2 is no budget being allocated for the implementation of a technical screening for acceptance testing of ICT components entering the SDLC as replacement parts. The obvious remedy is to determine a reasonable budget allocation.

An example of a vulnerability at tier 3 is a discrepancy in system functions not meeting requirements, resulting in substantial impact to performance. The mitigation approach is to initiate the necessary engineering change.

Supply Chain Security Controls

SP 800-161 provides a comprehensive list of security controls for SCRM. These controls are organized into the following families:

Access control

Awareness and training

Audit and accountability

Security assessment and authorization

Configuration management

Contingency planning

Identification and authentication

Incident response

Maintenance

Media protection

Physical and environmental protection

Planning

Program management

Personnel security

Provenance

Risk assessment

System and services acquisition

System and communications protection

System and information security

All these control families, with the exception of the provenance family, are adapted for the specific needs of SCRM from the security controls defined in SP 800-53.

Security control AC-3 (access enforcement) provides an example of the adaptation of a security control to SCRM security needs. In SP 800-53, the description of this security control begins as follows:

Control: The information system enforces approved authorizations for logical access to information and system resources in accordance with applicable access control policies.

Supplemental Guidance: Access control policies (for instance, identity-based policies, role-based policies, attribute-based policies) and access enforcement mechanisms (for example, access control lists, access control matrices, cryptography) control access between active entities or subjects (for example, users or processes acting on behalf of users) and passive entities or objects (for instance, devices, files, records, domains) in information systems. In addition to enforcing authorized access at the information system level and recognizing that information systems host many applications and services in support of organizational missions and business operations, access enforcement mechanisms are also employed at the application and service level to provide increased information security.

Control Enhancements:

(8) REVOCATION OF ACCESS AUTHORIZATIONS

The information system enforces the revocation of access authorizations resulting from changes to the security attributes of subjects and objects based on [Assignment: organization-defined rules governing the timing of revocations of access authorizations].

Supplemental Guidance: Revocation of access rules differ based on the types of access revoked. For example, if a subject (that is, user or process) is removed from a group, access may not be revoked until the next time the object (for example, file) is opened or until the next time the subject attempts a new access to the object. Revocation based on changes to security labels can take effect immediately. Organizations can provide alternative approaches on how to make revocations immediate if information systems cannot provide such capability and immediate revocation is necessary.

(9) ACCESS ENFORCEMENT | CONTROLLED RELEASE

The information system does not release information outside of the established system boundary unless:

The receiving (Assignment: organization-defined information system or system component) provides (Assignment: organization-defined security safeguards); and

(Assignment: organization-defined security safeguards) are used to validate the appropriateness of the information designated for release.

There are a total of 10 security enhancements for this control; we show only numbers 8 and 9 in this example.

The control section prescribes specific security-related activities or actions to be carried out by organizations or by information systems. The supplemental guidance section provides nonprescriptive additional information for a specific security control. Organizations can apply the supplemental guidance as appropriate. The security control enhancements section provides statements of security capability to add functionality/specificity to a control and/or increase the strength of a control. In both cases, control enhancements are used in information systems and environments of operation requiring greater protection than provided by the base control due to the potential adverse organizational impacts or when organizations seek additions to the base control functionality/specificity based on organizational assessments of risk.

SP 800-161 provides the following adapted version of AC-3:

Supplemental ICT SCRM Guidance: Ensure that the information systems and the ICT supply chain infrastructure have appropriate access enforcement mechanisms in place. This includes both physical and logical access enforcement mechanisms, which likely work in coordination for ICT supply chain needs. Organizations should ensure a detailed definition of access enforcement.

Control enhancements:

(8) REVOCATION OF ACCESS AUTHORIZATIONS

Supplemental ICT SCRM Guidance: Prompt revocation is critical to ensure that system integrators, suppliers, and external service providers who no longer require access are not able to access an organization’s system. For example, in a “badge flipping” situation, a contract is transferred from one system integrator organization to another with the same personnel supporting the contract. In that situation, the organization should retire the old credentials and issue completely new credentials.

(9) CONTROLLED RELEASE

Supplemental ICT SCRM Guidance: Information about the ICT supply chain should be controlled for release between the organizations. Information may be continuously exchanged between the organization and its system integrators, suppliers, and external service providers. Controlled release of organizational information provides protection to manage risks associated with disclosure.

As this example illustrates, each selected control from SP 800-53 is tailored to SCRM requirements by providing additional material. In addition, there is a new family of controls provided in SP 800-163 that does not appear in SP 800-53, known as provenance controls. SP 800-163 defines provenance as follows:

For ICT SCRM, the records describing the possession of, and changes to, components, component processes, information, systems, organization, and organizational processes. Provenance enables changes to the baselines of components, component processes, information, systems, organizations, and organizational processes, to be reported to appropriate actors, functions, locales, or activities.

The concept of provenance relates to the fact that all systems and components originate at some point in the supply chain and can be changed throughout their existence. The recording of system and component origin along with the history of, the changes to, and the recording of who made the changes is called provenance. The three security controls in the SP 800-163 provenance family deal with creating and maintaining provenance within the ICT supply chain. The objective is to enable enterprise agencies to achieve greater traceability in the event of an adverse event, which is critical for understanding and mitigating risks. The three security controls in this family are:

Provenance policy and procedures: Provides guidance for implementing a provenance policy.

Tracking provenance and developing a baseline: Provides details concerning the tracking process.

Auditing roles responsible for provenance: Indicates the role auditing plays in an effective provenance policy.

SCRM Best Practices

There a number of useful sources of guidance for best practices for SCRM, including the Information Security Forum’s (ISF’s) Standard of Good Practice for Information Security (SGP), NISTIR 7622, and the ISO 28000 series on supply chain security. The ISO series includes the following standards documents:

ISO 28000, Specification for Security Management Systems for the Supply Chain

ISO 28001, Best Practices for Implementing Supply Chain Security, Assessments and Plans –Requirements and Guidance

ISO 28003, Requirements for Bodies Providing Audit and Certification of Supply Chain Security Management Systems

ISO 28004, Guidelines for the Implementation of ISO 28000

At their SCRM website, the NIST lists practices adopted by companies for effective SCRM. One set of best practices deals with vendor selection and management and consists of the following:

A focus on brand integrity rather than brand protection supports life cycle threat modeling, which proactively identifies and addresses vulnerabilities in the supply chain.

Procurement and sourcing processes are developed jointly with input from IT, security, engineering, and operations personnel; sourcing decisions receive multi-stakeholder input.

Standard security terms and conditions are included in all requests for proposals (RFPs) and contracts, tailored to the type of contract and business needs.

Asset or business owners must formally accept responsibility for exceptions to security guidelines and any resulting business impact.

Since many risk assessments depend on supplier self-evaluation, a number of companies employ onsite verification and validation of these reviews. Some companies cross-train personnel to be stationed at supplier companies so that security criteria are monitored year round.

New suppliers enter a test and assessment period—to test the capabilities of the supplier and its compliance with various requirements—before they actively join the supply chain. In high-risk areas, for example, a supplier might go through a series of pilots before fully entering the supply chain.

Tier 1 suppliers are required to give their suppliers the same survey that the original equipment manufacturer (OEM) requires of them.

Approved vendor lists are established for manufacturing partners.

Quarterly reviews of supplier performance are assessed among a stakeholder group.

Annual supplier meetings ensure that suppliers understand the customers’ business needs, concerns, and security priorities.

Mentoring and training programs are offered to suppliers, especially in difficult or key areas of concern to the company, such as cybersecurity.

For managing supply chain risk, companies should adopt the following practices:

Security requirements are included in every RFP and contract.

Once a vendor is accepted in the formal supply chain, a security team works with that vendor onsite to address any vulnerabilities and security gaps.

Have a “one strike and you’re out” policy with respect to vendor products that are either counterfeit or do not match specification.

Component purchases are tightly controlled. For example, component purchases from approved vendors are prequalified, and parts purchased from other vendors are unpacked, inspected, and X-rayed before being accepted.

Secure software life cycle development programs and training for all engineers in the life cycle are established.

Source code is obtained for all purchased software.

Software and hardware have a security handshake. Secure booting processes look for authentication codes, and the system will not boot if codes are not recognized.

Automation of manufacturing and testing regimes reduces the risk of human intervention.

Track-and-trace programs establish provenance of all parts, components, and systems.

Programs capture “as built” component identity data for each assembly and automatically link the component identity data to sourcing information.

Personnel in charge of supply chain cybersecurity partner with every team that touches any part of the product during its development life cycle and ensure that cybersecurity is part of suppliers’ and developers’ employee experience, processes, and tools.

Legacy support is provided for end-of-life products and platforms to ensure a continued supply of authorized IP and parts.

Tight controls are imposed on access by service vendors. Access to software is limited to a very few vendors. Hardware vendors are limited to mechanical systems and have no access to control systems. All vendors are authorized and escorted.

Supply chain risk management must be conducted as part of the overall risk management function in an organization. Thus, ultimately, a chief information security officer (CISO) or a person in a similar position is responsible for overseeing risk management and risk assessment for all the functions of an organization, including supply chain risk management.

13.3 Cloud Computing

There is an increasingly prominent trend in many organizations, known as enterprise cloud computing, that involves moving a substantial portion or even all IT operations to an Internet-connected infrastructure. This section provides an overview of cloud computing.

Cloud Computing Elements

NIST defines cloud computing in NIST SP-800-145, The NIST Definition of Cloud Computing, as follows:

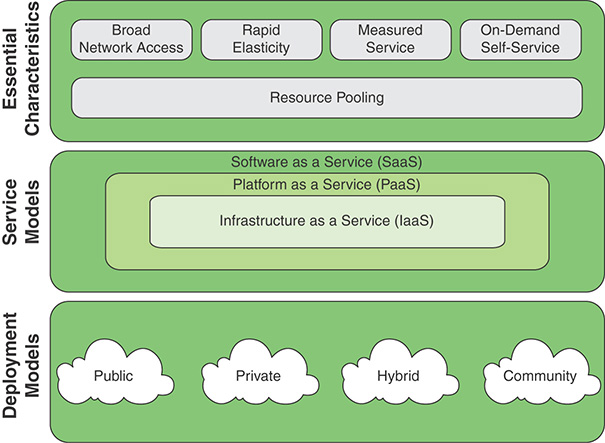

Cloud computing: A model for enabling ubiquitous, convenient, on-demand network access to a shared pool of configurable computing resources (for example, networks, servers, storage, applications, and services) that can be rapidly provisioned and released with minimal management effort or service provider interaction. This cloud model promotes availability and is composed of five essential characteristics, three service models, and four deployment models.

Figure 13.6 illustrates the relationships between the various models and characteristics mentioned in this definition.

The essential characteristics of cloud computing include the following:

Broad network access: Capabilities are available over the network and accessed through standard mechanisms that promote use by heterogeneous thin or thick client platforms (for example, mobile phones, laptops, and personal digital assistants (PDAs) as well as other traditional or cloud-based software services.

Rapid elasticity: Cloud computing gives you the ability to expand and reduce resources according to your specific service requirement. For example, you may need a large number of server resources only for the duration of a specific task. You want to be able to release those resources upon completion of the task.

Measured service: Cloud systems automatically control and optimize resource use by leveraging a metering capability at some level of abstraction appropriate to the type of service (for example, storage, processing, bandwidth, active user accounts). Resource usage is monitored, controlled, and reported, providing transparency for both the provider and the consumer of the utilized service.

On-demand self-service: A consumer can unilaterally provision computing capabilities, such as server time and network storage, as needed automatically without requiring human interaction with each service provider. Because the service is on demand, the resources are not permanent parts of the IT infrastructure.

Resource pooling: The provider’s computing resources are pooled to serve multiple consumers using a multitenant model, with different physical and virtual resources dynamically assigned and reassigned according to consumer demand. There is a degree of location independence in that the customer generally has no control or knowledge of the exact location of the provided resources but may be able to specify location at a higher level of abstraction (for example, country, state, data center). Examples of resources include storage, processing, memory, network bandwidth, and virtual machines. Even private clouds tend to pool resources between different parts of the same organization.

NIST defines three service models, which are viewed as nested service alternatives:

Software as a service (SaaS): The consumer can use the provider’s applications running on a cloud infrastructure. The applications are accessible from various client devices through a thin client interface such as a web browser. Instead of obtaining desktop and server licenses for software products it uses, an enterprise obtains the same functions from the cloud service. SaaS eliminates the complexity of software installation, maintenance, upgrades, and patches. Examples of services at this level are Gmail, Google’s email service, and Salesforce.com, which helps firms keep track of their customers.

Platform as a service (PaaS): The consumer can deploy onto the cloud infrastructure consumer-created or acquired applications created using programming languages and tools supported by the provider. PaaS often provides middleware-style services such as database and component services for use by applications. In effect, PaaS is an operating system in the cloud.

Infrastructure as a service (IaaS): The consumer can provision processing, storage, networks, and other fundamental computing resources and can deploy and run arbitrary software, including operating systems and applications. IaaS enables customers to combine basic computing services, such as number crunching and data storage, to build highly adaptable computer systems.

NIST defines four deployment models:

Public cloud: The cloud infrastructure is made available to the general public or a large industry group and is owned by an organization selling cloud services. The cloud provider is responsible for both the cloud infrastructure and the control of data and operations within the cloud.

Private cloud: The cloud infrastructure is operated solely for a single organization. It is either managed by the organization or a third party and exists on premises or off premises. The cloud provider is responsible only for the infrastructure and not for the control.

Community cloud: The cloud infrastructure is shared by several organizations and supports a specific community with shared concerns (for example, mission, security requirements, policy, compliance considerations). It is managed by the organizations or a third party and exists on premises or off premises.

Hybrid cloud: The cloud infrastructure is a composite of two or more clouds (private, community, or public) that remain unique entities but are bound together by standardized or proprietary technology that enables data and application portability (for example, cloud bursting for load balancing between clouds).

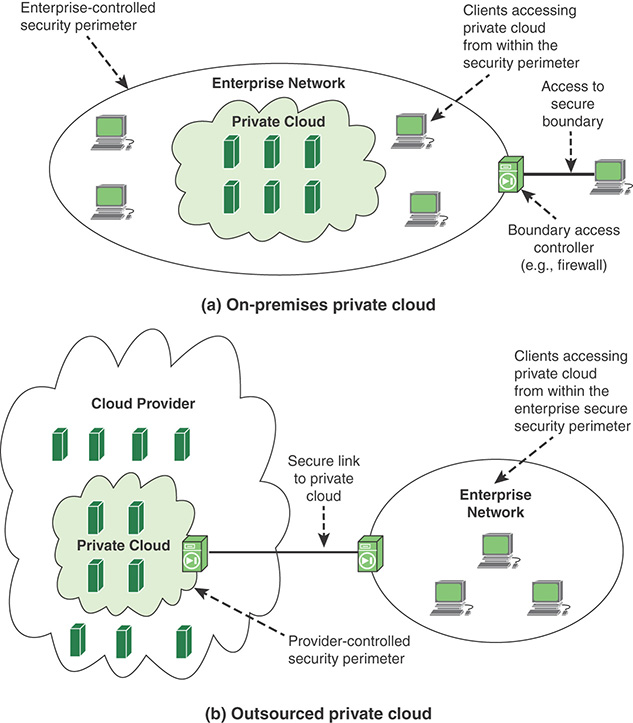

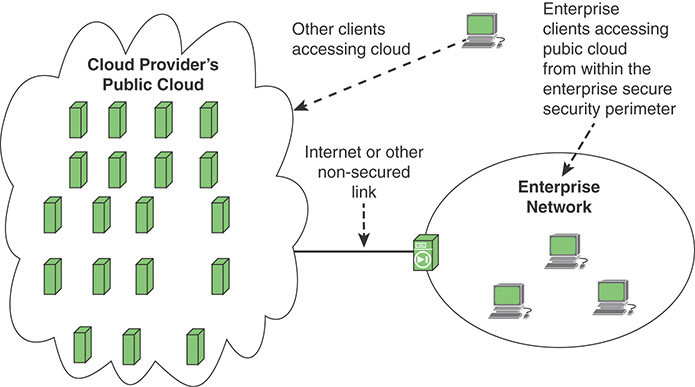

Figure 13.7 illustrates the two typical private cloud configurations. The private cloud consists of an interconnected collection of servers and data storage devices hosting enterprise applications and data. Local workstations have access to cloud resources from within the enterprise security perimeter. Remote users (for example, from satellite offices) have access through a secure link, such as a virtual private network (VPN) connecting to a secure boundary access controller, such as a firewall. An enterprise may also choose to outsource the private cloud to a cloud provider. The cloud provider establishes and maintains the private cloud, consisting of dedicated infrastructure resources not shared with other cloud provider clients. Typically, a secure link between boundary controllers provides communications between enterprise client systems and the private cloud. This link may be a dedicated leased line or a VPN over the Internet.

Figure 13.8 shows a public cloud used to provide dedicated cloud services to an enterprise. The public cloud provider serves a diverse pool of clients. Any given enterprise’s cloud resources are segregated from those used by other clients, but the degree of segregation varies among providers. For example, a provider dedicates a number of virtual machines to a given customer, but a virtual machine for one customer may share the same hardware as virtual machines for other customers.

Cloud Computing Reference Architecture

A cloud computing reference architecture depicts a generic high-level conceptual model for discussing the requirements, structures, and operations of cloud computing. NIST SP 500-292, NIST Cloud Computing Reference Architecture, establishes a reference architecture, described as follows:

The NIST cloud computing reference architecture focuses on the requirements of “what” cloud services provide, not a “how to” design solution and implementation. The reference architecture is intended to facilitate the understanding of the operational intricacies in cloud computing. It does not represent the system architecture of a specific cloud computing system; instead it is a tool for describing, discussing, and developing a system-specific architecture using a common framework of reference.

NIST developed the reference architecture with the following objectives in mind:

To illustrate and understand the various cloud services in the context of an overall cloud computing conceptual model

To provide a technical reference for consumers to understand, discuss, categorize, and compare cloud services

To facilitate the analysis of candidate standards for security, interoperability, and portability and reference implementations

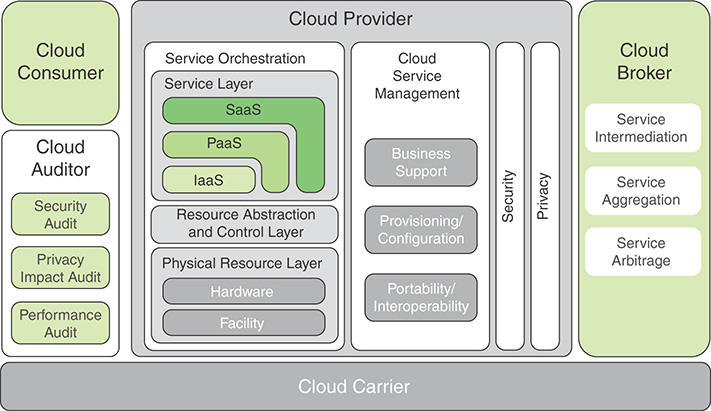

The reference architecture depicted in Figure 13.9 defines five major actors in terms of their roles and responsibilities:

Cloud consumer: A person or an organization that maintains a business relationship with, and uses services from, cloud providers

Cloud provider (CP): A person, an organization, or an entity responsible for making a service available to interested parties

Cloud auditor: A party that conducts independent assessment of cloud services, information system operations, performance, and security of the cloud implementation

Cloud broker: An entity that manages the use, performance, and delivery of cloud services and negotiates relationships between CPs and cloud consumers

Cloud carrier: An intermediary that provides connectivity and transport of cloud services from CPs to cloud consumers

FIGURE 13.9 NIST Cloud Computing Reference Architecture

The roles of the cloud consumer and provider have already been discussed. To summarize, a cloud provider, or cloud service provider (CSP), provides one or more cloud services to meet the IT and business requirements of cloud consumers. For each of the three service models (SaaS, PaaS, and IaaS), the CP provides the storage and processing facilities needed to support that service model, together with a cloud interface for cloud service consumers. For SaaS, the CP deploys, configures, maintains, and updates the operation of the software applications on a cloud infrastructure so that the services are provisioned at the expected service levels to cloud consumers. The consumers of SaaS are organizations that provide their members with access to software applications, end users who directly use software applications, or software application administrators who configure applications for end users.

For PaaS, the CP manages the computing infrastructure for the platform and runs the cloud software that provides the components of the platform, such as runtime software execution stack, databases, and other middleware components. Cloud consumers of PaaS use the tools and execution resources provided by CPs to develop, test, deploy, and manage the applications hosted in a cloud environment.

For IaaS, the CP acquires the physical computing resources underlying the service, including the servers, networks, storage, and hosting infrastructure. The IaaS cloud consumer in turn uses these computing resources, such as a virtual computer, for fundamental computing needs.

The cloud carrier is a networking facility that provides connectivity and transport of cloud services between cloud consumers and CPs. Typically, a CP sets up service level agreements (SLAs) with a cloud carrier to provide services consistent with the level of SLAs offered to cloud consumers and can require the cloud carrier to provide dedicated and secure connections between cloud consumers and CPs.

A cloud broker is useful when cloud services are too complex for a cloud consumer to easily manage. Three areas of support are offered by a cloud broker:

Service intermediation: These are value-added services, such as identity management, performance reporting, and enhanced security.

Service aggregation: The broker combines multiple cloud services to meet consumer needs not specifically addressed by a single CP or to optimize performance or minimize cost.

Service arbitrage: This is similar to service aggregation except that the services being aggregated are not fixed. Service arbitrage means a broker has the flexibility to choose services from multiple agencies. The cloud broker, for example, can use a credit-scoring service to measure and select an agency with the best score.

A cloud auditor evaluates the services provided by a CP in terms of security controls, privacy impact, performance, and so on. The auditor is an independent entity which ensures that the CP conforms to a set of standards.

13.4 Cloud Security

This section focuses on cloud security from the point of view of a cloud consumer—that is, an organization that makes use of services from a cloud service provider.

Security Considerations for Cloud Computing

The following key issues that need to be addressed when an organization moves data and/or applications into the cloud:

Confidentiality and privacy: An organization has commitments to its employees and customers in the areas of data confidentiality and privacy. Further, any breach of confidentiality or privacy can have adverse business impacts. Finally, regulations and legal restrictions apply. Placing data in the cloud introduces new risks that must be assessed.

Data breach responsibilities: Placing data and services in the cloud amplifies concerns about data breaches, yet security is not under the direct control of the customer. The following are some issues in this regard:

Responsibility for notifying: Data breach generally carries with it an obligation to notify. Who is responsible for notification (customer, vendor, third party) and how quickly?

Risks to intellectual property: Risks include authorization, terms and conditions that (inappropriately) assert ownership over intellectual property held by third parties, and weakening of ability for organizations to assert “work made for hire” for creations that are developed “without use of organizational resources.”

Export controls: Does the vendor house data at foreign sites? Are the systems managed by foreign nationals?

E-discovery: Institutions and their legal counsel can be obligated to keep records needed for legal discovery. But these records are not under direct organizational control; the organization no longer has the record in the same way that it formerly did. How does one handle discovery in this externalized infrastructure?

Risk assessment: To perform effective risk assessment, the customer must have considerable information about the security policies and controls in effect at the cloud service provider.

Business continuity: Plans are needed to deal with the suspension or termination of the cloud service. The customer needs to have the portability capability to move data to a different cloud service provider.

Legal issues: Legal risks and obligations must be clarified and documented.

Threats for Cloud Service Users

The use of cloud services and resources introduces a novel set of threats to enterprise cybersecurity. For example, a report issued by the ITU-T [ITUT12] lists the following threats for cloud service users:

Responsibility ambiguity: The enterprise-owned system relies on services from the cloud provider. The level of the service provided (SaaS, PaaS, IaaS) determines the magnitude of resources that are offloaded from IT systems on to the cloud systems. Regardless of the level of service, it is difficult to define precisely the security responsibilities of the customer and those of the cloud service provider. If there is any ambiguity, this complicates risk assessment, security control design, and incident response.

Loss of governance: The migration of a part of the enterprises IT resources to the cloud infrastructure gives partial management control to the cloud service provider. The degree of loss of governance depends on the cloud service model (SaaS, PaaS, IaaS). In any case, the enterprise no longer has complete governance and control of IT operations.

Loss of trust: It is sometimes difficult for a cloud service user to assess the provider’s trust level due to the black-box feature of the cloud service. There is no way to obtain and share the provider’s security level in a formalized manner. Furthermore, cloud service users are generally unable to evaluate the security implementation level achieved by the provider. This in turn makes it difficult for the customer to perform a realistic risk assessment.

Service provider lock-in: A consequence of the loss of governance could be a lack of freedom in terms of how to replace one cloud provider with another. An example of a difficulty in transitioning is if a cloud provider relies on nonstandard hypervisors or virtual machine image format and does not provide tools to convert virtual machines to a standardized format.

Nonsecure cloud service user access: As most of the resource deliveries are through remote connections, unprotected application programming interfaces (APIs) (mostly management APIs and PaaS services) are among the easiest attack vectors. Attack methods such as phishing, fraud, and exploitation of software vulnerabilities pose significant threats.

Lack of asset management: The cloud service user may have difficulty in assessing and monitoring asset management by the cloud service provider. Key elements of interest include location of sensitive asset/information, degree of physical control for data storage, reliability of data backup (data retention issues), and countermeasures for business continuity and disaster recovery. Furthermore, cloud service users are also likely to have important concerns about exposure of data to foreign governments and compliance with privacy laws.

Data loss and leakage: This threat can be strongly related to the preceding item. However, loss of an encryption key or a privileged access code brings serious problems to cloud service users. Accordingly, lack of cryptographic management information, such as encryption keys, authentication codes, and access privilege, lead to sensitive damages, such as data loss and unexpected leakage to the outside.

Risk Evaluation

It is useful to have a detailed questionnaire for performing risk evaluation for cloud services. The Information Security Council developed a template to be used for this purpose [HEIS14b]. The template includes the questions in the following areas (the full document is available at this book’s document resource site):

High-level description

Authentication

Authorization—logical access control

Data security

Recoverability

Operational controls

Incident response

Application security

Testing and validation

Cybersecurity Book Resource Site https://app.box.com/v/wscybersecurity

The questionnaire is quite detailed. For example, the application security section includes the following questions:

8.0 APPLICATION SECURITY

8.1 Does the software development life-cycle model used by the hosting service provider in the development of their software, incorporate features from any standards based framework models (for example, TSP-Secure, SAMM, Microsoft SDL, OWASP, NIST SP800-64 rev 2, )? If so, please specify.

8.1.1 Are security components identified and represented during each phase of the software development life -cycle?

8.2 Does the service provider have change management policies in place?

8.2.1 Is a pre-determined maintenance window used to apply changes?

8.2.2 How much lead-time will the service provider give customer of upcoming changes?

8.2.3 How are customers notified of changes?

8.2.4 Does the service provider have a process to test their software for anomalies when new operating system patches are applied?

8.2.5 Has a technical and/or security evaluation been completed or conducted when a significant change occurred?

8.3 Are source code audits performed regularly?

8.3.1 Are source code audits performed by someone other than the person or team that wrote the code?

8.4 Is access to the service provider’s application restricted to encrypted channels (for example, https)?

8.5 Describe the session management processes used by the hosted service’s applications.

During the proposal phase of contract procurement, the cloud service provider should be required to fill out this questionnaire. If the answers are satisfactory, they should be incorporate into the contract as provider commitments.

Best Practices

When using a public cloud or an outsourced private cloud, an enterprise is faced with a complex environment in which to evaluate threats, vulnerabilities, and risks. Much of the challenge relates to the adequacy of the cloud provider’s security controls. Thus, the enterprise must exercise due diligence when selecting and moving functions and resources to a cloud. As a guide, SP 800-144, Guidelines on Security and Privacy in Public Cloud Computing, provides a list of best practices for outsourcing to a cloud service provider, in three categories:

Preliminary activities:

Identify security, privacy, and other organizational requirements for cloud services to meet as a criterion for selecting a cloud provider.

Analyze the security and privacy controls of a cloud provider’s environment and assess the level of risk involved with respect to the control objectives of the organization.

Evaluate the cloud provider’s ability and commitment to deliver cloud services over the target time frame and meet the security and privacy levels stipulated.

Initiating and coincident activities:

Ensure that all contractual requirements are explicitly recorded in the service agreement, including privacy and security provisions, and that they are endorsed by the cloud provider.

Involve a legal advisor in the review of the service agreement and in any negotiations about the terms of service.

Continually assess the performance of the cloud provider and the quality of the services provisioned to ensure that all contract obligations are being met and to manage and mitigate risk.

Concluding activities:

Alert the cloud provider about any contractual requirements that must be observed upon termination.

Revoke all physical and electronic access rights assigned to the cloud provider and recover physical tokens and badges in a timely manner.

Ensure that organizational resources made available to or held by the cloud provider under the terms of service agreement are returned or recovered in a usable form and ensure that information has been properly expunged.

Cloud Service Agreement

From point of view of the overall mission and objectives of an enterprise—and in particular from the point of view of security—an essential aspect of using outsourced cloud services is a formal cloud service agreement (CSA). The Cloud Standards Customer Council list the following as the typical major components of a CSA [CSCC15]:

Cloud Standards Customer Council http://www.cloud-council.org

Customer agreement: Describes the overall relationship between the customer and provider. Terms include how the customer is expected to use the service, methods of charging and paying, reasons a provider can suspend service, termination, and liability limitations.

Acceptable use policies: Prohibits activities that providers consider to be an improper or illegal use of their service. In addition, the provider usually agrees not to violate the intellectual property rights of the customer.

Cloud service level agreements: Defines a set of service level objectives, including availability, performance, security, and compliance/privacy. The SLA specifies thresholds and financial penalties associated with violations of these thresholds. Well-designed SLAs significantly contribute to avoiding conflict and facilitate the resolution of issues before they escalate into disputes.

Privacy policies: In general, the privacy policy describes the different types of information collected; how that information is used, disclosed, and shared; and how the provider protects that information. Portions of this agreement can define what information is collected about the customer, what personally identifiable information (PII) is to be stored, and the physical location information.

13.5 Supply Chain Best Practices

The SGP breaks down the best practices in the supply chain management category into two areas and four topics and provides detailed checklists for each topic. The areas and topics are:

External supplier management: The objective of this area is to identify and manage information risk throughout each stage of relationships with external suppliers (including suppliers of hardware and software throughout the supply chain, outsourcing specialists, and cloud service providers) by embedding information security requirements in formal contracts and obtaining assurance that they are met.

External supplier management process: Describes procedures for identifying and managing information risks throughout all stages of the relationship with external suppliers (including organizations in the supply chain).

Outsourcing: Describes procedures for governing the selection and management of outsourcing providers (including cloud service providers), supported by documented agreements that specify the security requirements to be met.

Cloud computing: The objective of this area is to establish and enforce a comprehensive cloud security policy, which specifies the need to incorporate specialized information security requirements in cloud-specific contracts and communicate it to all individuals who purchase or use cloud services.

Cloud computing policy: Defines the elements to be included in a policy on the use of cloud services, to be produced and communicated to all individuals who purchase or use cloud services.

Cloud service contracts: Provides a detailed list of obligations on the part of the cloud service provider to be included in the service contract.

13.6 Key Terms and Review Questions

Key Terms

After completing this chapter, you should be able to define the following terms:

information and communications technology (ICT)

infrastructure as a service (IaaS)

intellectual property rights (IPR)

key performance indicators (KPIs)

supply chain risk management (SCRM)

Review Questions

Answers to the Review Questions can be found online in Appendix C, “Answers to Review Questions.” Go to informit.com/title/9780134772806.

1. What does ICT stand for, and what does it mean?

2. Explain the concept of a supply chain. How is an ICT supply chain different from a general supply chain?

3. Explain three types of flows associated with a supply chain.

4. Describe key elements involved in supply chain management.

5. What are the three tiers of risk management defined in SP 800-161?

6. What are the main external risks of a supply chain?

7. What are the main internal risks of a supply chain?

8. List the supply chain security controls mentioned in SP 800-161 standard.

9. Enumerate three security controls in the provenance family.

10. Define the term cloud computing.

11. What are key characteristics of cloud computing?

12. What are the three service models of cloud computing, according to NIST?

13. Describe the cloud deployment models included in the NIST standard.

14. What are the central elements in NIST’s cloud computing reference architecture?

15. What are some of the threats for cloud service users?

16. What are the key components of a cloud service agreement, according to the Cloud Standards Customer Council?

13.7 References

CSCC15: Cloud Standards Customer Council, Practical Guide to Cloud Service Agreements. April 2015. http://www.cloud-council.org/deliverables/CSCC-Practical-Guide-to-Cloud-Service-Agreements.pdf

HEIS14b: Higher Education Information Security Council, “Cloud Computing Security.” Information Security Guide, 2014. https://spaces.internet2.edu/display/2014infosecurityguide/Cloud+Computing+Security

ITUT12: ITU-T, Focus Group on Cloud Computing Technical Report Part 5: Cloud Security. FG Cloud TR, February 2012.

WILD13: Wilding, R., “Classification of the Sources of Supply Chain Risk and Vulnerability.” August 2013. http://www.richardwilding.info/blog/the-sources-of-supply-chain-risk