Chapter 4

Motivation Nation: Engagement and Motivation

In This Chapter

![]() Examining intrinsic versus extrinsic motivators

Examining intrinsic versus extrinsic motivators

![]() Considering key drivers of intrinsic motivation

Considering key drivers of intrinsic motivation

![]() Making use of Maslow's hierarchy of needs

Making use of Maslow's hierarchy of needs

![]() Fostering a learning culture in your organization

Fostering a learning culture in your organization

A key aspect of engagement is motivation — why people do what they do. A person may be motivated by any number of things: to attain status or money, to help others, to find meaning in life, or simply to express herself.

In this chapter, I explain the difference between someone who's motivated intrinsically and someone who's motivated extrinsically. Then I fill you in on key drivers of intrinsic motivation (in case you hadn't guessed, this is the kind you're after). I introduce you to Maslow's hierarchy of needs and tell you how you can use it to engage your employees. Finally, I show you how you can motivate your employees by fostering a learning culture. Motivated to find out more? Read on!

Outie or Innie? Understanding Extrinsic versus Intrinsic Motivation

According to psychology types, there are two types of motivation:

-

Extrinsic (external ) motivation: Extrinsic motivation comes from outside a person. For employees, the most obvious form of extrinsic motivation is money. Every paid job on this planet involves extrinsic motivation, whether in the form of salary, tips, commission, benefits, stock options, bribes, table scraps, or some combination thereof.

Another example of extrinsic motivation is the threat of punishment. For example, an employee who regularly shows up late will be fired; so, fear of being fired may serve as an extrinsic motivation.

Companies often use extrinsic motivation to encourage specific behaviors, such as competitiveness or punctuality. When people talk about engaged employees having both their heads and their hearts in their jobs, extrinsic motivation is the “head” part of that equation.

-

Intrinsic ( internal ) motivation: Intrinsic motivation comes from within. It's driven by a personal interest or enjoyment in the task itself. For example, suppose you enjoy playing the pan flute, and you want to improve your skills. That's an example of an intrinsic motivation. You don't want to become a better pan-flute player so you can be a world-famous musician — you simply want, for your own personal reasons, to improve your pan-flute skills because you enjoy playing the pan flute.

With intrinsic motivation, the result is often growth — for example, growth as an intellectual journey or growth due to challenges that have been overcome. When people talk about engaged employees having both their heads and their hearts in their jobs, intrinsic motivation is the “heart” part of that equation.

Both extrinsic and intrinsic motivation play a role in building a culture of engagement. Obviously, extrinsic motivation (in the form of money) is important — after all, people need to be paid in order to put food on the table. But intrinsic motivation plays an even greater part in the world of employee engagement.

The fact is, intrinsically motivated employees are more likely to be engaged in what they're doing than their counterparts who rely only on extrinsic motivation to put a spring in their step. Moreover, intrinsically motivated employees are more likely to go above and beyond — to put in that discretionary effort.

Key Club: Identifying Key Intrinsic Motivational Drivers

The key to building an engaged workforce is putting in place the necessary measurement and reward systems to capture employees’ extrinsic motivation, while also understanding the unique intrinsic drivers that motivate each of your employees. Often, these intrinsic motivational drivers will differ from person to person, so you need to get to know your employees well enough to understand their intrinsic motivational drivers.

In this section, I cover seven key intrinsic motivators, identified by combing through massive amounts of literature, studies, theories, concepts, and strategies on intrinsic motivation. ( You may recognize some of these motivators if you're familiar with the work of Cynthia Berryman-Fink and Charles B. Fink, authors of The Manager's Desk Reference [AMACOM].)

The seven motivational drivers are as follows:

- Achievement: Employees with this driver want the satisfaction of completing projects successfully. They want to exercise their talents to attain success. They're self-motivated if the job is challenging enough. Employees who are willing — in fact, longing — to take on that stretch assignment (a project or task given to an employee that is beyond his current knowledge or skill level, designed to “stretch” the employee in order to learn and grow) or to relocate for that promotion would most likely list “achievement” as their primary motivational driver, as would high achievers and many C-suite executives. Common occupations for people motivated by achievement include executive director, professional athlete, sales professional, CEO, inventor, scientist, and entrepreneur.

- Authority: Employees with this driver get satisfaction from influencing and sometimes even controlling others. They like to lead and persuade, and are motivated by positions of power and leadership. Individuals motivated by authority are those who volunteer to be project manager, lead the project team, and/or take on more direct reports. If you've ever served on a jury, the person who volunteered to be the foreman was most likely motivated by authority. Common occupations for people motivated by authority may include project manager, politician, and law enforcement officer.

- Camaraderie: Employees with this driver are satisfied through affiliation with others. They enjoy people and find the social aspect of the workplace rewarding. If you're looking for individuals to fill a task team, be on a committee, or participate in this year's charity campaign, your volunteers most likely will be those who are motivated by camaraderie. These are the same people who volunteer to be on your town's recreation committee or help plan the annual food drive for your local church. (Of course, the person who volunteers to lead the food drive probably has camaraderie as a secondary motivational driver, with authority as the primary one.) Be careful if you're hiring or promoting someone who is motivated by camaraderie to start a new location as a one-person office or to work remotely. Odds are, he won't flourish. Common occupations for people motivated by camaraderie include HR professional, healthcare professional, hotel and restaurant worker, nonprofit professional, and other service industry positions.

- Independence: Employees with this driver want freedom and independence. They like to work and take responsibility for their own tasks and projects. When looking for employees to work at home, relocate to a remote location, or work in isolation to complete a project, you would be wise to select individuals whose primary motivational driver is independence. Common occupations for people motivated by independence include entrepreneur, freelancer, tradesperson (for example, electricians, plumbers, or carpenters), and research scientist.

- Esteem: Employees with this driver need sincere recognition and praise. They dislike generalities — they want praise for specific accomplishments. (Note that they don't necessarily require public praise.) You would want employees motivated by esteem on your new task team that will present its findings to the executive team. Experts who volunteer their time to share their knowledge via brown-bag luncheons, webinars, and so on are motivated by esteem. Common occupations for people motivated by esteem include training and development professional, politician, nonprofit professional, author, actor, and comedian.

- Safety/security: Employees with this driver crave job security, a steady income, health insurance, other fringe benefits, and a hazard-free work environment. These employees always worry about getting let go. They may even refuse pay increases for fear that their salaries will become so high that they'll be on the radar on the next round of layoffs. Common occupations for people motivated by safety and security include clergyperson, government personnel, military personnel, utility worker, and union worker.

- Fairness: Employees with this driver simply want to be treated fairly. They probably compare their own work hours, job duties, salary, and privileges to those of other employees to ensure they're getting a fair shake. If they perceive inequities, they'll quickly become discouraged. Employees motivated by fairness pay attention to how much you pay new employees, what their bonus was compared to others, and whose turn it is to be invited to the senior management team meeting. Common occupations for people motivated by fairness include accountant, payroll personnel, and human resources professional.

If you want to increase engagement among your employees, you'll want to develop a good sense of their internal drivers. How can you do that? Well, why not ask them? At your next department meeting, explain the seven motivational drivers (including how we all have elements of all seven within us), and ask them to write down what they believe to be their primary and secondary drivers. Then have them list what they think are the primary and secondary drivers of their teammates. Emphasize that there are no “wrong” answers. Finally, give team members the opportunity to share their drivers if they want. This entertaining and revealing exercise may lead to some surprises, and will enable the members of your team to better understand each other. After the meeting, follow up with team members individually to discuss their motivations in more detail. This will help you determine how best to engage them.

A No-Malarkey Hierarchy: Putting Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs to Work for You

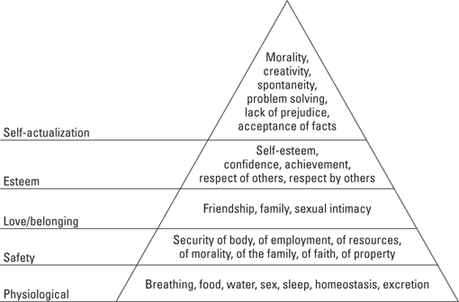

Maslow's hierarchy of needs is a psychology theory posed by Abraham Maslow in his 1943 paper, “A Theory of Human Motivation.” According to this theory, all people have needs that must be satisfied. Maslow used a pyramid to describe and categorize these needs, as shown in Figure 4-1. Needs on the bottom of the pyramid must be met before needs on the next level can be addressed.

Illustration by Wiley, Composition Services Graphics

Figure 4-1: Maslow's hierarchy of needs.

Here are the five levels in Maslow's hierarchy of needs, and how you can apply them to the workplace to engage your employees:

- Psychological: To survive, people need air, food, water, sleep, and so on. How does this relate to employee engagement? Employees need a comfortable work environment. If your employees work in conditions of extreme hot or cold, they probably won't advance to the next level in the pyramid — they simply won't have the motivation. Similarly, employees need access to such things as restroom breaks, food, drinks, and so on.

- Safety: People must feel that they, their family, their property, and other resources are safe. When it comes to the workplace, if employees have to worry about their personal safety (for example, getting hurt or sick at work) or their professional security (read: losing their jobs), morale will suffer. Ensuring a safe workplace may include providing ergonomic furniture and/or securing the building. Job security is also key.

-

Love/belonging: Not surprisingly, creating a sense of belonging is a key aspect of building an engaged culture. In its highly regarded Q12, which is a measure of employee engagement, Gallup includes the following question: “Do you have a best friend at work?” Why does this question matter? Because based on Gallup's research, employees who answer in the affirmative are more likely to be engaged than those who don't. This is directly attributed to Maslow's third level of love and belonging. Companies with a history of social and other camaraderie-building activities have higher degrees of employee engagement than companies that are all business, all the time.

Although employee perks like ping-pong tables and beer-cart Fridays are not employee engagement drivers in and of themselves (instead, they're satisfiers), they do help create an atmosphere of love and belonging.

Although employee perks like ping-pong tables and beer-cart Fridays are not employee engagement drivers in and of themselves (instead, they're satisfiers), they do help create an atmosphere of love and belonging. -

Esteem: Esteem is a person's belief that she is doing a good job and that her contributions are recognized. People want to feel that they're achieving and that their contributions matter and are recognized. Confidence is key. Any educator or coach will tell you, if a student or player has confidence, that person will shine. The same principle holds true in the workplace. If employees believe in themselves — and believe (thanks to recognition) that others believe in them — they'll be more engaged and productive.

Employee recognition is a key part of engagement. At its core, recognition builds esteem. Unfortunately, even though recognition has so much impact — and is often free — it remains low on most companies’ list of priorities. (For more on employee recognition, see Chapter 17.)

Employee recognition is a key part of engagement. At its core, recognition builds esteem. Unfortunately, even though recognition has so much impact — and is often free — it remains low on most companies’ list of priorities. (For more on employee recognition, see Chapter 17.) -

Self-actualization: In the workplace, self-actualization translates to maximizing one's true potential. Employees want to be the very best at what they do, and the manager's job is to help them realize that. With self-actualization, employees feel trusted and empowered — in control of their jobs and their futures.

A key aspect of self-actualization is ensuring that employees are only put in positions for which they are capable. Sure, employees should feel challenged, but you don't want them to be in over their heads. Ultimately, this erodes engagement, as employees begin to doubt themselves. The three circles discussed in the nearby sidebar are a great way for managers to ensure that their employees are positioned to excel and, therefore, become self-actualized.

A healthy, fully engaged workforce is one that has collectively reached level five, or self-actualization. This occurs in organizations that have built a line of sight between where the company is going and each employee's job or role. Level five is where you win over employees’ heads and hearts. Fortune magazine's annual Top 100 Best Companies to Work For is full of companies that have reached level five.

Unfortunately, we're not all so lucky to work for such enlightened companies. Therefore, it's incumbent on managers to really get to know their employees so they can maximize their engagement. The old “Treat people the way you want to be treated” rule no longer applies. These days, it's “Treat people the way they want to be treated.” That means knowing what motivates them.

A Yearn to Learn: Fostering a Learning Culture

In 2013, SilkRoad, a cloud-based talent management solutions provider, asked 2,200 global clients, “What are the best mechanisms to foster employee engagement?” Not surprisingly, four of the top seven answers pertained to career development and learning opportunities. The power of career development, learning, and growth opportunities in improving engagement was also confirmed in the Dale Carnegie research referenced in Chapter 3.

It's quite simple: If you help your employees develop their skills by offering them learning opportunities, you'll increase employee engagement. Employees become engaged when they see a line of sight between where their career is today and where it's going. Managers who help employees get there will see a spike in the engagement of those being developed.

There's an old training adage that perhaps says it best:

- Non-enlightened manager: “If I train my employees, they might leave.”

- Enlightened manager: “Would you rather not train them and have them stay?”

Managers who build a culture of learning understand that investing in employees today pays dividends tomorrow. A culture of learning can encompass many forms of education, including traditional classroom training and workshops, conferences and seminars, stretch assignments, job rotation, tuition reimbursement, internal transfers, and the growing trends of e-learning and web-based training.

- Are employees challenged in their day-to-day work? What would provide more challenge? In some occupations, continually thinking of new ways to challenge the troops is a constant struggle. Managers who oversee call centers or manufacturing environments often wrestle with challenging their employees. These managers need to introduce job rotation, incentives for process improvements, and task team involvement to minimize the boredom that often comes with these types of positions. Job rotation is particularly critical for Millennials, who are especially prone to changing jobs. If they're going to quit sooner rather than later anyway, why not let them “quit” but stay in the company? Job rotation allows them to do just that.

- Are employees receiving the right amount of training? To find out, conduct stay interviews (see Chapter 3). Employee engagement surveys are another great way to gauge how your employees perceive their development — especially if you benchmark your results against others in your industry. If you see that your competitors are investing more in the development of their people, that's a strong indication that they may be doing a better job than your firm of building their workforce of tomorrow.

-

Where do you see your employees in two to three years? What about in three to five years? These questions are simple, yet powerful. Ambition is a competency that you should measure. Managers can often gauge their employees’ level of ambition and whether they're being challenged in their current roles by asking these forward-looking questions.

Note, however, that some employees don't seek or need new challenges and opportunities in order to be engaged. These employees find enrichment in their current job, see no need to change, and have no hunger to take on new challenges. A perfect example is an enthusiastic and helpful receptionist who, despite 25 years on the job, is always engaged. This person is fulfilled by meeting new people, helping them as best she can, and being the “first face” of the company!

- What nomenclature are you using to describe training in your organization? Companies should swap the phrase training and development for the simpler learning to better describe the way employees develop in today's workplace.

- Who else should employees be learning from within the organization? Companies should communicate to all employees who their internal functional, technical, market, customer, and/or geographical experts are, and encourage those smarty-pants to host “lunch and learn” events. (“If you feed them, they will come” is a popular training adage that always holds true. Springing for pizza is a sure-fire way to increase attendance.)

-

Would a certain employee be a candidate for a company committee or task team? Is there a national or international initiative in which an employee is interested in participating? As I've said, a great by-product of employee engagement is discretionary effort. Inviting employees to join internal task teams and/or committees is a great way to tap into this discretionary effort to solve a company problem or launch a new initiative.

Avoid appointing or assigning people to committees. Instead, have them volunteer. An employee is far more likely to be engaged in a committee if he really cares about the committee's charter. Also, avoid inviting the same people (a.k.a., your very best employees) to join every committee. If you do, you risk committee fatigue, which will tax their engagement. Chances are, they're already your busiest employees, and they may not positively perceive their nomination to your committee! That said, when seeking volunteers, do validate their capabilities by having their boss endorse their nomination. Nothing is more deflating for a committee than having fellow committee members be fired for performance issues or quit the company before their committee tenure is up.

Avoid appointing or assigning people to committees. Instead, have them volunteer. An employee is far more likely to be engaged in a committee if he really cares about the committee's charter. Also, avoid inviting the same people (a.k.a., your very best employees) to join every committee. If you do, you risk committee fatigue, which will tax their engagement. Chances are, they're already your busiest employees, and they may not positively perceive their nomination to your committee! That said, when seeking volunteers, do validate their capabilities by having their boss endorse their nomination. Nothing is more deflating for a committee than having fellow committee members be fired for performance issues or quit the company before their committee tenure is up.