Chapter 6

Winning Their Hearts and Minds: Driving Engagement with a Sense of Purpose

In This Chapter

![]() Connecting your employees’ behavior to your mission statement

Connecting your employees’ behavior to your mission statement

![]() Engaging employees’ heads and hearts

Engaging employees’ heads and hearts

As I mention in Chapter 4, money is not always a primary engagement driver — although the perception of unfairness or an organizational caste system (in which there are clear “haves” and “have nots”) is certain to lead to disengagement. Purpose, however, is an engagement driver. Indeed, organizations that build their cultures around purpose generally have higher levels of engagement than those that don't.

These companies are in on a powerful secret: Companies that know their own purpose, values, vision, and strategic plan (what I call their “line of sight”), and that believe in corporate social responsibility, are better positioned to win over the hearts and minds of their employees. And not surprisingly, employees who are duly won over are significantly more likely to be engaged.

Sightseeing: Building Your Line of Sight

One morning, while staying at a hotel in Portland, Oregon, that was part of a national chain, I stepped into the hotel elevator on my way to a meeting. In the elevator were two hotel employees actively engaged in conversation. By their feet was a piece of crumpled-up paper, which was clearly trash.

Neither employee greeted me with a “Good morning!” or even made eye contact. Worse, they made no attempt to pick up the piece of trash on the floor. Seeing an opportunity for a social experiment, I calmly picked up the piece of paper before exiting the elevator on the ground floor. “Gentlemen,” I said, “can you tell me why you didn't pick up this piece of paper?” The first employee fibbed: “I didn't see it.” The second answered, “Sir, they don't pay me enough money to pick up trash.”

A few months later, I was staying at the Four Seasons in Philadelphia, where I was speaking at a conference. When I returned to the hotel from my morning run, the valet was waiting for me with a bottle of water and a towel. I thanked him, and without missing a beat, he replied: “No need to thank me, sir. Here at the Four Seasons, it's all about the customer experience!” Afterward, I reflected on my earlier experience at the Portland hotel chain. I couldn't help but notice the difference in customer service.

I decided to conduct another social experiment. I grabbed a tissue, crumpled it up, headed to the elevator, and tossed it on the floor. Feeling a bit foolish, I rode up and down for several minutes, waiting for a hotel employee to enter the elevator car. Finally, one did. “Good morning, sir!” he said cheerfully. He then quickly picked up the crumpled-up tissue and hid it behind his back. Wow, what a contrast!

When I arrived home, I did some research about these two hotel chains. Believe it or not, the pay for hotel employees was similar at both chains. So, why was the customer experience at one so different from the other? Well, one reason is that the Four Seasons is renowned for its service culture. This is underscored by its mission statement, which includes the following components:

- What we believe: Our greatest asset, and the key to our success, is our people. We believe that each of us needs a sense of dignity, pride, and satisfaction in what we do. Because satisfying our guests depends on the united efforts of many, we are most effective when we work together cooperatively, respecting each other's contribution and importance.

- How we behave: We demonstrate our beliefs most meaningfully in the way we treat each other and by the example we set for one another. In all our interactions with our guests, customers, business associates, and colleagues, we seek to deal with others as we would have them deal with us.

In other words, the Four Seasons has been very successful in building a “line of sight” between its mission statement and the behaviors of its employees.

For organizations to develop a “line of sight,” they must answer the following questions:

- Why do we exist (purpose)?

- Who are we (values)?

- Where are we going (vision)?

- How will we get there (strategic plan)?

In addition, organizations must assess how they are doing — in other words, develop a scorecard of sorts. (For more on developing a scorecard, see Chapter 15.)

How does building this “line of sight” boost engagement? Simple. It all has to do with aligning your organization with its purpose. When people care deeply about something, or are invested in an activity, cause, or job — intellectually and emotionally — they're generally more passionate about the outcome than when they are not invested. If you don't believe me, consider people who donate their time to their community food kitchen, their church, local youth sports organizations, or charities. Do they get paid? No. So, why do they do it? Why do they invest time and energy in something that doesn't pay the mortgage? They do it because it has a purpose. It's a higher calling.

As an aside, just as it's important to create a company-level line of sight, it's also critical to create a personal-level one — that is, to help individuals develop a clear picture of where they are today in their careers and where they're going. You want employees to understand the company's strategic plan, and to know where they fit in that plan. For more information on this personal-level line of sight, see Chapter 16.

Identifying your firm's purpose

Okay, stop reading for a minute. Go to your company's website, and try to find out why it's in business. Not what you do, make, or sell — but why.

Most companies know what they do, make, or sell. But they struggle when they try to define their reason for being — what I call their “why” — even though being able to do so makes business sense. In his excellent book Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap . . . And Others Don't (HarperBusiness), author Jim Collins notes that companies that focus on purpose outperform their peer group by a factor of six. You read that right: They do six times better than their peers.

Despite this, most companies struggle when it comes to identifying their why. Indeed, very few companies are able to identify a purpose that resonates with their employees both intellectually and emotionally. Why? Well, for starters, identifying an organization's why is often difficult. Sure, identifying the purpose of a charity for the homeless is easy. Most likely, it's something along the lines of “providing jobs for the homeless” or “providing shelter to those in need.” But not every firm's purpose, or mission, is so readily understood or so easily articulated.

Take Raytheon, a large global defense company. My son works for Raytheon, in its Patriot missile division. It's easy to identify what Raytheon does, makes, and sells. But its reason for being? Its purpose, mission, or why? Identifying that is a bit more difficult. Even so, Raytheon's Patriot missile division has crystalized its purpose. As my son puts it, “We protect those who protect us.”

Take Raytheon, a large global defense company. My son works for Raytheon, in its Patriot missile division. It's easy to identify what Raytheon does, makes, and sells. But its reason for being? Its purpose, mission, or why? Identifying that is a bit more difficult. Even so, Raytheon's Patriot missile division has crystalized its purpose. As my son puts it, “We protect those who protect us.”

Here are a few examples of other firms that have identified their purpose:

Here are a few examples of other firms that have identified their purpose:

- 3M: “Our purpose is to solve unsolved problems innovatively.”

- Merck: “Our purpose is to preserve and improve human life.”

- Disney: “Our purpose is to make people happy.”

- Mary Kay Cosmetics: “To inspire women to transform their lives, and in doing so, help other women transform their lives.” (Note that Mary Kay Cosmetics refers to its purpose as its “dream.”)

- The Coca‐Cola Company: “To refresh the world, inspire moments of optimism and happiness, create value, and make a difference.”

Unfortunately, the very people who most need to understand a company's purpose — CEOs, COOs, CFOs, managing directors, and other key executives — are often the last to grasp its importance. These left-brain types typically spend their time worrying about numbers rather than “soft” issues like purpose and values. Ensuring that these stakeholders understand and appreciate your firm's purpose is critical. Otherwise, you'll likely be unable to build a line of sight around your purpose.

-

Send out a quick survey to a sampling of employees from all representative groups, including generations, tenure, background, levels, culture, and departments.

You can build the survey using SurveyMonkey (

www.surveymonkey.com). It's free!Ask the following questions:

- Why do we exist as an organization?

- In 100 years, what do we want to be remembered for?

- How are we different from our competitors?

- What is the one thing we do as an organization that everyone admires?

- What inspires you about working here?

-

Assemble a “Purpose” task team to evaluate the answers to these questions, with the goal of developing two or three draft purpose statements.

This team should include owners, key leaders, and a cross‐sectional group of high performers.

- Distribute the top purpose statements to all employees for further input and perhaps to vote for the statement that resonates the most.

- Have the company leadership select the best purpose statement using the input provided and begin the communication and branding outreach.

Defining your firm's values

Values are beliefs that are shared among the stakeholders of an organization. They drive an organization's culture and priorities, and provide a framework in which decisions are made. Examples of values include the following:

- “Innovation is the cornerstone of everything we do.”

- “Collaboration is the hallmark of our culture.”

If you want your people to behave in a certain way or produce specific outcomes, you have to define, communicate, and then model those behaviors and outcomes. The same is true for your core values. In order for your people to live and embody them, three critical actions must occur:

- Your leadership team must define and commit to a set of four to eight core values. These values should represent the “rules of the tavern,” or the organizational behaviors you most value. If your company has no stated values, the leadership team should begin with a short list of key values that they believe are representative, such as innovation, collaboration, respect, teamwork, fun, quality, service, creativity, and so on. This short list should be sent out to employees with a request that they rank them.

- The agreed‐upon values should be communicated on an ongoing basis. A fun way to do this is to have employees use their smartphones to film their interpretation of your values. Post the top videos on your intranet page or perhaps even choose a winner and showcase his or her video on YouTube or on your firm's website.

- If you're going to talk the talk, you have to walk the walk. Make sure that whatever values you identify, your leadership team lives them daily.

When articulating their values, some organizations are able to inject their own personalities. For example, the e-commerce firm Zappos espouses the following values (referred to as the company's “Family Values”):

When articulating their values, some organizations are able to inject their own personalities. For example, the e-commerce firm Zappos espouses the following values (referred to as the company's “Family Values”):

- Deliver WOW Through Service

- Embrace and Drive Change

- Create Fun and A Little Weirdness

- Be Adventurous, Creative, and Open‐Minded

- Pursue Growth and Learning

- Build Open and Honest Relationships With Communication

- Build a Positive Team and Family Spirit

- Do More With Less

- Be Passionate and Determined

- Be Humble

On a more traditional level, you can see the power of simplicity of the Kellogg Company's values: Integrity, Accountability, Passion, Humility, Simplicity, and Results.

On a more traditional level, you can see the power of simplicity of the Kellogg Company's values: Integrity, Accountability, Passion, Humility, Simplicity, and Results.

Identifying your organization's vision

An organization's vision, expressed in the form of a vision statement, outlines what the organization wants to be and/or how it wants the world in which it operates to be. As author Andy Stanley notes, vision is “what could be and what should be, regardless of what is. Vision creates possibilities and inspires people to behave and take action in ways that allow the vision to become a reality.”

It should be a longer-term view with a focus on the future. For example, a charity that works with the poor might have the vision, “a world without poverty.” As another example, consider Amazon's vision statement:

Our vision is to be earth's most customer centric company; to build a place where people can come to find and discover anything they might want to buy online.

A successful vision statement has six key characteristics:

- It's imaginable. Does it prompt employees to think about the future? Is it part inspirational and part aspirational? Is it unique to your firm?

- It's energizing. Is it exciting, captivating, and engaging? Does it make employees want to jump out of bed in the morning?

- It's feasible, yet bold. There is a fine line between inspiring employees to reach for new heights and creating jaded skeptics. A vision that is too bold risks cynicism (“Are they kidding?”). A vision should be bold but achievable.

- It's focused. For example, Amazon's vision explicitly states that its business model will continue to be built around online shopping. A vision that's too vague can result in employees and customers not understanding who you are or where you're going.

- It's flexible. Successful visions allow for flexibility in chasing and responding to shifting market and labor forces. If Amazon's vision started as “online bookstore,” the company would have struggled with its subsequent diversification strategy.

- It's easy to communicate and remember. Can a stranger remember your company's vision statement after spending 40 seconds with you in an elevator? If not, it needs work. This is never more true than today, with the increasing prevalence of social media and mobile applications.

Building your strategic plan

Of course, it's not enough to say where you want to go. You also have to develop a strategic plan to get there. This includes allocating the necessary resources — people, money, paper clips, what have you — to get where you're going. Most organizations develop a new strategic plan every three to five years. Building a strategic plan involves the following key steps:

- Conduct a SWOT (short for “strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats”) analysis of your current business position.

- Identify the market(s), customer(s), and geographical area(s) you're focusing on.

- Outline the objectives — between three and eight — you want to accomplish over the next three to five years.

- Decide on the specific goals and actions to accomplish your objectives.

- Budget for and allocate your resource needs, including human resources, capital resources, system requirements, acquisitions, and so on.

- Develop your measurement tools. (See Chapter 15 for more information.)

- Install a communications protocol. (Refer to Chapter 5.)

Promoting your purpose, values, and vision

Okay, you've identified your purpose, values, and vision, and developed your five-year strategic plan (see Chapter 15). Now what? Promoting, that's what. Promoting your purpose, values, and vision is key to developing your line of sight and fostering engagement.

Remember those Four Seasons employees I mention earlier? Those guys did not accidentally stumble upon the fact that the Four Seasons has a service culture. Instead, the Four Seasons understood the importance of promoting its purpose, values, and vision.

So, what is your company's purpose? What are its values? What is its vision? Can all your employees articulate these? Is there consistency? To boost the stickiness of your organization's purpose, values, and vision, consider adopting these best practices:

- Build an internal promotion campaign with your purpose, values, and vision as the theme. The campaign should be repetitive (employees don't “hear” something unless they've been exposed to it 13 times) and employ all forms of communication: written, oral, videos, blogs, social media, mobile applications, town hall meetings, lunch and learn, posters, and so on. Depending on your culture, make the campaign fit who you are. For example, Harley Davidson might include themes of adventure or rebellion, use earthy tones, and so on.

- Sponsor a “Why We Work Here” video contest, in which employees create their own short films that incorporate the firm's purpose, values, and vision. Generation Y will love this idea.

- Print your company's purpose, values, and vision on the back of everyone's business cards.

- Boost your co‐branding efforts by combining your marketing and sales efforts with your employment branding efforts. For more information, see Chapter 10.

- Leverage tri‐branding, linking employees, customers, and other key stakeholders. Again, see Chapter 10 for more info.

-

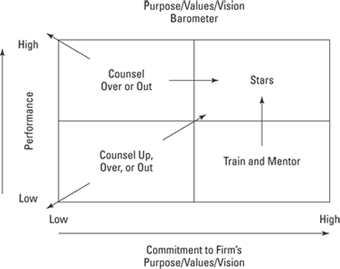

Create a four‐quadrant value barometer with “Performance” on one axis and “Commitment to the Firm's Purpose/Values/Vision” on the other (see Figure

6‐1

). Use this barometer when evaluating an internal candidate for a promotion, raise, bonus, or pay increase.

Illustration by Wiley, Composition Services Graphics

Figure 6-1: The purpose/values/vision barometer.

- Hire people who display specific behaviors and traits that reflect your values and culture. For more about pinpointing these key behaviors and traits, see Chapter 12.

- Make your firm's purpose, values, and vision the centerpiece of its onboarding/new hire orientation program. Chapter 14 discusses onboarding in more detail.

- Incorporate questions in your employee engagement survey that not only reinforce your purpose, values, and vision, but also gauge employees’ familiarity with your purpose, values, and vision.

- Suggest that all organizational meetings include a “line of sight” agenda item, with purpose, values, and vision embedded into a discussion of the firm's business results.

Be Responsible! Engaging Employees through Corporate Social Responsibility

Remember the movie Wall Street? In it, Gordon Gekko, played by the incomparable Michael Douglas, famously declares, “Greed is good.”

Well, with all due respect to Mr. Gekko, I'd argue that seldom in the course of Western history has greed been less popular. These days, many people give the stink-eye to corporate policies and practices that enable an elite group to accrue wealth at everyone else's expense. They demand a higher level of responsibility — namely, corporate social responsibility (CSR).

Corporate social responsibility is the idea that organizations have moral, ethical, environmental, and philanthropic responsibilities above and beyond their responsibility to legally earn a fair return for investors. You can bet that your clients, vendors, stakeholders, and especially your employees are assessing your level of CSR — things ranging from your carbon footprint to your level of volunteerism to your efforts to give back to your community. In addition to their paycheck and benefits, a large portion of your staff will want to see that the company they work for is making a difference in the world. With every passing day (and every depressing headline), this engagement driver becomes even more important.

Don't just take my word for it. As I once heard Andrew W. Savitz, author of The Triple Bottom Line (Jossey-Bass), say, “To stay focused on business alone is no longer sustainable . . . People want to work for responsible companies.” Thomas Friedman, author of The World Is Flat (Picador), concurs, noting that tomorrow's companies will need to have “the brains of a business school graduate and the heart of a social worker.” And in his book Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies (HarperBusiness), author Jim Collins summarizes the importance of CSR by noting that it provides purpose above and beyond profit. “In a truly great company,” Collins writes, “profits and cash flow become like blood and water to a human body: They are absolutely essential for life, but they are not the very point of life.”

Warby Parker is one organization that takes CSR seriously. A web-based eyeglass company, Warby Parker launched a “Buy a Pair, Give a Pair” program. For each purchase made, Warby Parker donates glasses to someone in need. So far, the company has donated more than 150,000 pairs. Toms, a shoe and eyewear company, has a similar program, donating one pair of shoes or glasses for each pair bought.

Warby Parker is one organization that takes CSR seriously. A web-based eyeglass company, Warby Parker launched a “Buy a Pair, Give a Pair” program. For each purchase made, Warby Parker donates glasses to someone in need. So far, the company has donated more than 150,000 pairs. Toms, a shoe and eyewear company, has a similar program, donating one pair of shoes or glasses for each pair bought.

Of course, a “buy one, give one” model is only one way to go. Other options include donating employees’ time. This approach is used by Salesforce.com, which donates 1 percent of each employee's time for community service — 350,000 hours at last count. Salesforce.com goes two better, though, also donating 1 percent of the company's equity (we're talking $40 million so far) to charitable and related organizations in the form of grants, and donating 1 percent of the company's products to nonprofit organizations.

Of course, a “buy one, give one” model is only one way to go. Other options include donating employees’ time. This approach is used by Salesforce.com, which donates 1 percent of each employee's time for community service — 350,000 hours at last count. Salesforce.com goes two better, though, also donating 1 percent of the company's equity (we're talking $40 million so far) to charitable and related organizations in the form of grants, and donating 1 percent of the company's products to nonprofit organizations.

Microsoft is another great example. Although the ascension of Google, Facebook, and other high-tech companies has made it tougher for Microsoft to recruit and retain top employees and engineers in recent years, the Redmond-based software giant believes its philanthropic efforts are attracting talent now more than ever. Indeed, this is one area where Microsoft sets the pace for the entire technology sector. As noted by Brad Smith, Microsoft's general counsel, at the conclusion of the company's 30th annual Employee Giving Campaign, “When you're living through a time when unemployment is up and when people see more human needs, there is a greater focus now on what companies and employees are doing to address those human needs.” Smith, who believes that Microsoft's reputation as a charitable organization is a key recruiting tool, continued by saying that he “frequently hears from young interns and employees that Microsoft's broad citizenship efforts are part of what people find attractive to the company. “The opportunity to work on great products and services is hugely important and always will be,” Smith said, adding “but [prospective employees] also really value the broader connections that a company has in the community.”

Microsoft is another great example. Although the ascension of Google, Facebook, and other high-tech companies has made it tougher for Microsoft to recruit and retain top employees and engineers in recent years, the Redmond-based software giant believes its philanthropic efforts are attracting talent now more than ever. Indeed, this is one area where Microsoft sets the pace for the entire technology sector. As noted by Brad Smith, Microsoft's general counsel, at the conclusion of the company's 30th annual Employee Giving Campaign, “When you're living through a time when unemployment is up and when people see more human needs, there is a greater focus now on what companies and employees are doing to address those human needs.” Smith, who believes that Microsoft's reputation as a charitable organization is a key recruiting tool, continued by saying that he “frequently hears from young interns and employees that Microsoft's broad citizenship efforts are part of what people find attractive to the company. “The opportunity to work on great products and services is hugely important and always will be,” Smith said, adding “but [prospective employees] also really value the broader connections that a company has in the community.”

Some companies even go so far as to build their mission around CSR. Take Patagonia. It's mission statement is as follows:

Some companies even go so far as to build their mission around CSR. Take Patagonia. It's mission statement is as follows:

Build the best product, cause no unnecessary harm, use business to inspire and implement solutions to the environmental crisis.

Whole Foods has a similar mission:

Whole Foods has a similar mission:

Whole Foods, Whole People, Whole Planet.

And then there's the Starbucks mission statement:

And then there's the Starbucks mission statement:

To inspire and nurture the human spirit — one person, one cup, and one neighborhood at a time.

A company whose very mission is CSR will be very attractive to many engaged workers!

- Allow employees to take one paid service day per year with an approved nonprofit or charitable organization.

- Establish a matching contribution program with a charitable organization such as the Red Cross in the aftermath of a natural disaster or national emergency, when funds are needed.

- Establish a CSR committee to communicate, suggest, and solicit ideas.

- “Brand” any CSR programs in your organization. Obviously, this includes formal CSR programs launched by your company, but it should also include any informal CSR programs that may exist. Believe me, they're there — you just may not be aware of them! You can bet that your employees are already championing activities like walks for hunger, corporate challenges, food drives, and other forms of volunteerism. Consider forming a task team consisting of a cross‐section of volunteers to hunt down these ad‐hoc activities.

- Establish a “green” program with a focus on recycling, water conservation, and other environmentally sensitive initiatives.

- Launch a “chain reaction” initiative in which you ask for volunteers (they're out there!) to identify, promote, and coordinate location‐specific community events — for example, planning a walk to raise money for cancer research, participating in a charity road race, or working at the local soup kitchen.

- Use CSR initiatives to reward employees. For example, you might give employees who win your Innovation Idea of the Month contest a free day for community service or a nominal cash award (say, $100), which they can donate to their favorite charity.

- In the spirit of “walk the talk,” schedule time at the next executive offsite meeting for the executive team to work on a socially responsible activity. For example, the team could partner with Habitat for Humanity to help rebuild a community hit by a tornado or flood.

The great thing about CSR programs is, you get as much as you give — if not more. Jonathan Reckford, CEO of Habitat for Humanity, notes: “The one consistent takeaway I hear from all company volunteers is that they receive more than they give when they work on one of our homebuilding projects.”

Interestingly, CSR is important across the generational spectrum. As I discuss in Chapter 8, Generation Y workers are purpose-driven by their very nature. But Baby Boomers, too, have demonstrated a growing interest in social responsibility as they enter the “back nine” of their careers. Having attained hierarchical and monetary success, many Boomers are asking, “How do I give back?” Even better, because many of these Boomers are now in executive leadership positions, they're even going so far as to ask, “How can I persuade my company to give back?” Increasingly, Baby Boomers are pushing their employers to donate to charities, reduce their carbon footprint, and support volunteerism. This cross-generational interest in social responsibility is a powerful means of staff cohesion, as well as a key engagement driver — one that you cannot afford to neglect.

Need help pinpointing your organization's purpose? Try following these steps:

Need help pinpointing your organization's purpose? Try following these steps: Organizations that build their culture on purpose, and that hire people with the behaviors and traits that match their culture (see Chapter

Organizations that build their culture on purpose, and that hire people with the behaviors and traits that match their culture (see Chapter  Be warned: CSR isn't just some program you can cut when the bottom line slips. It must be embedded in the very essence of your company. If your leadership sees it as a “flavor of the month” initiative, your employees will quickly detect its transitory nature. Implementing a policy of social responsibility means following through. If you don't, the internal perception — and maybe even the external perception — will be negative, to say the least!

Be warned: CSR isn't just some program you can cut when the bottom line slips. It must be embedded in the very essence of your company. If your leadership sees it as a “flavor of the month” initiative, your employees will quickly detect its transitory nature. Implementing a policy of social responsibility means following through. If you don't, the internal perception — and maybe even the external perception — will be negative, to say the least!