New Paradigms: In Search of a Third Way

Abstract

In this chapter, different types of growth are discussed, based on all economic activities in the gross national product or only by desirable activities in the measure of desirable activities. Wealth and inequality up to the present time are illustrated by a case study for Denmark, including assets such as education, health, material and economic possessions. This is followed by a critical appraisal of how goods and offered for sale, how salaried work is administered and how tolerance toward different ways of doing things is faring at present. The next section discusses constitutions, departing from a historical exposition of the major steps taken in ancient Greece, France and the USA, leading to a discussion of connecting human rights with duties, of decentralization versus globalization, and of direct versus representative democracy.

Keywords

3.1. New indicators of social welfare

3.1.1. Growth, but of What?

3.1.2. Measure of Desirable Activities

Table 3.1

Example of Applying Corrections Due to Resource Depletion and Environmental and Social Impacts to the National Activity Accounts of Denmark for 2011.

| Monetary evaluation of national activities | Private and public consumption and stock changes. Environmental and social impacts in production and service phases deducted | ||

| Denmark 2011, production/service sector | Impact factor | Import origin (M DKK) | National source (M DKK) |

| Agriculture and horticulture | 0.5 | 743 | 1,680 |

| Forestry | 0.3 | 42 | 1,191 |

| Fishing | 0.3 | 92 | 95 |

| Extraction of oil and gas | 0.9 | −80 | −147 |

| Extraction of gravel and stone | 0.5 | 74 | 79 |

| Mining support service activities | 0.5 | 0 | 111 |

| Production of meat and meat products | 0.7 | 486 | 1,935 |

| Processing and preserving of fish | 0.1 | 640 | 410 |

| Manufacture of dairy products | 0.1 | 1,610 | 5,995 |

| Manufacture of grain mill and bakery products | 0.1 | 1,480 | 5,280 |

| Other manufacture of food products | 0.1 | 6,958 | 4,728 |

| Manufacture of beverages | 0.1 | 2,182 | 3,498 |

| Manufacture of tobacco products | 0.1 | 413 | −162 |

| Manufacture of textiles | 0.3 | 643 | 466 |

| Manufacture of wearing apparel | 0.4 | 3,610 | 319 |

| Manufacture of leather and footwear | 0.5 | 753 | 55 |

| Manufacture of wood and wood products | 0.3 | 743 | 446 |

| Manufacture of paper and paper products | 0.5 | 444 | 47 |

| Printing, etc. | 0.8 | 19 | 10 |

| Oil refinery, etc. | 0.8 | 539 | 2,194 |

| Manufacture of basic chemicals | 0.7 | 32 | 255 |

| Manufacture of paints and soap, etc. | 0.7 | 215 | 324 |

| Pharmaceuticals | 0.5 | 3,117 | 4,791 |

| Manufacture of rubber and plastic products | 0.6 | 169 | 385 |

| Manufacture of glass and ceramic products | 0.3 | 193 | 46 |

| Manufacture of concrete and bricks | 0.4 | 82 | 314 |

| Manufacture of basic metals | 0.5 | 177 | 157 |

| Manufacture of fabricated metal products | 0.5 | 1,280 | 713 |

| Manufacture of computers and communication equipment, etc. | 0.6 | 3,217 | 631 |

| Manufacture of other electronic products | 0.6 | 2,840 | 2,056 |

| Manufacture of electric motors, etc. | 0.6 | 162 | 342 |

| Manufacture of wires and cables | 0.6 | 83 | 33 |

| Manufacture of household appliances, lamps, etc. | 0.5 | 1,262 | 480 |

| Manufacture of engines, windmills and pumps | 0.5 | 527 | 3,333 |

| Manufacture of other machinery | 0.5 | 5,520 | 5,195 |

| Manufacture of motor vehicles and related parts | 0.5 | 8,041 | 296 |

| Manufacture of ships and other transport equipment | 0.5 | 139 | 393 |

| Manufacture of furniture | 0.5 | 2,170 | 1,339 |

| Manufacture of medical instruments, etc. | 0.5 | 581 | 579 |

| Manufacture of toys and other manufacturing | 0.5 | 1,150 | 1,236 |

| Repair and installation of machinery and equipment | 0.4 | 945 | 436 |

| Production and distribution of electricity | 0.3 | 445 | 7,855 |

| Manufacture and distribution of gas | 0.4 | 65 | 2,010 |

| Steam and hot water supply | 0.3 | 0 | 6,077 |

| Water collection, purification and supply | 0.3 | 0 | 2,127 |

| Sewerage | 0.3 | 0 | 4,683 |

| Waste management and materials recovery | 0.3 | 15 | 3,963 |

| Construction of new buildings | 0.6 | 76 | 19,614 |

| Civil engineering | 0.1 | 861 | 32,421 |

| Professional repair and maintenance of buildings | 0.6 | 56 | 17,125 |

| Own account repair and maintenance of buildings | 0.6 | 9 | 2,934 |

| Sale of motor vehicles | 0.2 | 0 | 13,020 |

| Repair and maintenance of motor vehicles, etc. | 0.7 | 0 | 3,621 |

| Wholesale | 0.3 | 4 | 34,713 |

| Retail sale | 0.4 | 8 | 48,757 |

| Passenger rail transport, interurban | 0.5 | 31 | 2,208 |

| Transport by suburban trains, buses and taxi operation, etc. | 0.7 | 30 | 2,945 |

| Freight transport by road and via pipeline | 0.8 | 13 | 109 |

| Water transport | 0.2 | 18 | 1,504 |

| Air transport | 0.9 | 68 | 41 |

| Support activities for transportation | 0.5 | 41 | 2,749 |

| Postal and courier activities | 0.8 | 0 | 168 |

| Hotels and similar accommodation | 0.4 | 0 | 3,918 |

| Restaurants | 0.4 | 0 | 18,548 |

| Publishing | 0.4 | 308 | 3,778 |

| Publishing of computer games and other software | 0.2 | 990 | 1,954 |

| Film, television and sound recording activities | 0.4 | 0 | 2,870 |

| Radio and television broadcasting | 0.2 | 7 | 3,652 |

| Telecommunications | 0.2 | 1,484 | 13,362 |

| Information technology service activities | 0.2 | 2,603 | 7,576 |

| Information service activities | 0.2 | 177 | 727 |

| Monetary intermediation | 0.8 | 1 | 5,650 |

| Mortgage credit institutes, etc. | 0.7 | 0 | 4,503 |

| Insurance and pension funding | 0.6 | 5 | 7,551 |

| Other financial activities | 0.8 | 0 | 388 |

| Buying and selling of real estate | 0.8 | 0 | 1,284 |

| Renting of nonresidential buildings | 0.2 | 0 | 419 |

| Renting of residential buildings | 0.2 | 0 | 51,325 |

| Owner-occupied dwellings | 0.2 | 0 | 84,073 |

| Legal activities | 0.8 | 62 | 693 |

| Accounting and bookkeeping activities | 0.6 | 1 | 115 |

| Business consultancy activities | 0.3 | 0 | 766 |

| Architectural and engineering activities | 0.3 | 33 | 2,820 |

| Scientific research and development (market) | 0.2 | 3,458 | 5,614 |

| Scientific research and development (non-market) | 0.2 | 0 | 2 856 |

| Advertising and market research | 0.8 | 0 | 22 |

| Other technical business services | 0.8 | 0 | 101 |

| Veterinary activities | 0.3 | 0 | 777 |

| Rental and leasing activities | 0.6 | 4 | 699 |

| Employment activities | 0.5 | 5 | 5 779 |

| Travel agent activities | 0.6 | 0 | 5,546 |

| Security and investigation activities | 0.8 | 0 | 14 |

| Services to buildings, cleaning and landscape activities | 0.8 | 0 | 520 |

| Other business service activities | 0.8 | 0 | 120 |

| Public administration | 0.5 | 0 | 38,405 |

| Defence, public order, security and justice activities | 0.8 | 0 | 9,324 |

| Rescue service etc. (market) | 0.6 | 4 | 595 |

| Primary education | 0.2 | 0 | 44,881 |

| Secondary education | 0.2 | 0 | 22,891 |

| Higher education | 0.2 | 0 | 29,283 |

| Adult and other education (nonmarket) | 0.2 | 0 | 4,297 |

| Adult and other education (market) | 0.2 | 271 | 1,567 |

| Hospital activities | 0.5 | 48 | 42,401 |

| Medical and dental practice activities | 0.5 | 57 | 16,514 |

| Residential care activities | 0.5 | 0 | 15,192 |

| Social work activities without accommodation | 0.3 | 0 | 67,718 |

| Theatres, concerts and arts activities | 0.3 | 139 | 5,604 |

| Libraries, museums and other cultural activities (market) | 0.2 | 0 | 593 |

| Libraries, museums and other cultural activities (nonmarket) | 0.2 | 0 | 8,485 |

| Gambling and betting activities | 0.8 | 0 | 826 |

| Sports activities (market) | 0.5 | 13 | 1,143 |

| Sports activities (nonmarket) | 0.5 | 0 | 2,593 |

| Amusement and recreation activities | 0.7 | 0 | 999 |

| Activities of membership organizations | 0.8 | 0 | 4,124 |

| Repair of personal goods | 0.4 | 1 | 1,972 |

| Other personal service activities | 0.5 | 62 | 4,161 |

| Activities of households as employers of domestic personnel | 0.5 | 0 | 2,340 |

Source: Basic input–output data are from Statistics Denmark (2015a).

The fraction shown in the column ‘Impact factor’ is for each sector of production or service applied to the corresponding activity figure in monetary terms and deducted to get the values given in the two last columns, representing output consumption and stock change split according to whether the input is import or a local enterprise. 1 DKK is about €0.13 or US $ 0.15 (mid-2015).

Table 3.2

Example of Applying Corrections Due to Resource Depletion and Environmental and Social Impacts to the National Activity Accounts of Denmark for 2011.

| Monetary evaluation of national activities | Consumption impact factor | Private consumption (both production and use impact estimates subtracted) (M DKK) |

| Denmark 2011, private sector | ||

| Bread and cereals | 0.2 | 8,600 |

| Meat | 0.4 | 2,708 |

| Fish | 0.3 | 1,617 |

| Eggs | 0.3 | 471 |

| Milk, cream, yoghurt, etc. | 0.3 | 3,942 |

| Cheese | 0.4 | 2,056 |

| Oils and fats | 0.5 | 1,036 |

| Fruit and vegetables except potatoes | 0.3 | 5,661 |

| Potatoes, etc. | 0.2 | 956 |

| Sugar | 0.4 | 184 |

| Ice cream, chocolate and confectionery | 0.3 | 6,603 |

| Food products | 0.3 | 2,127 |

| Coffee, tea and cocoa | 0.5 | 1,014 |

| Mineral waters, soft drinks, fruit and vegetable juices | 0.5 | 2,534 |

| Spirits and wine | 0.5 | 3,397 |

| Beer | 0.5 | 1,591 |

| Tobacco, etc. | 1.0 | −2,864 |

| Articles of clothing | 0.3 | 11,570 |

| Cleaning, repair and hire of clothing | 0.6 | 7 |

| Footwear | 0.2 | 3,314 |

| Actual rentals for housing | 0.2 | 38,118 |

| Imputed rentals for housing | 0.2 | 63,322 |

| Maintenance and repair of the dwelling | 0.4 | 925 |

| Refuse collection, other services | 0.5 | 3,845 |

| Water supply and sewerage services | 0.5 | 1,135 |

| Electricity | 0.3 | 12,909 |

| Gas | 0.7 | 758 |

| Liquid fuels | 0.9 | −1,498 |

| District heating, etc. | 0.6 | 4,368 |

| Furniture and furnishings, carpets and other floor coverings | 0.5 | 2,608 |

| Household textiles | 0.5 | 656 |

| All major household appliances and small electric household appliances | 0.5 | 943 |

| Repair of major household appliances | 0.5 | 52 |

| Glassware, tableware and household utensils | 0.3 | 1,641 |

| Tools and equipment for house and garden | 0.5 | 712 |

| Nondurable household goods | 0.6 | 350 |

| Domestic services and household services | 0.4 | 153 |

| Pharmaceutical products and other medical products | 0.3 | 2,670 |

| Therapeutic appliances and equipment | 0.3 | 1,215 |

| Out-patient services | 0.4 | 1,081 |

| Hospital services | 0.4 | 375 |

| Purchase of vehicles | 0.3 | 12,977 |

| Spare parts, maintenance and repair of personal transport equipment | 0.6 | −2,603 |

| Fuels and lubricants for personal transport equipment | 1.0 | −7,799 |

| Other services in respect of personal transport equipment | 0.9 | −2,840 |

| Transport services | 0.9 | −9,484 |

| Postal services | 0.7 | −249 |

| Telephone and data communication equipment | 0.4 | −25 |

| Telephone and data communication services | 0.5 | 4,937 |

| Radio and television sets, etc. | 0.4 | 1,658 |

| Photographic equipment, etc. | 0.5 | 154 |

| Data processing equipment | 0.4 | 2,036 |

| Recording media for pictures and sound | 0.4 | 778 |

| Repair of a/v and data processing equipment | 0.7 | −87 |

| Other major durables for recreation and culture | 0.4 | 1,060 |

| Other recreational items and equipment, gardens and pets | 0.7 | −316 |

| Recreational and cultural services | 0.1 | 16,884 |

| Books, newspapers, periodicals and miscellaneous printed matter | 0.6 | 474 |

| Stationery and drawing materials, etc. | 0.4 | 280 |

| Package holidays | 0.8 | −5,330 |

| Education | 0.1 | 4,360 |

| Restaurants and catering | 0.8 | −5,517 |

| Accommodation services | 0.5 | 1,236 |

| Hairdressing salons and personal grooming establishments | 0.7 | −824 |

| Appliances, articles and products for personal care | 0.3 | 3,153 |

| Jewellery, clocks and watches | 0.2 | 860 |

| Other personal effects | 0.3 | 1,189 |

| Retirement homes, day-care centres, etc. | 0.3 | 1,526 |

| Kindergartens, nurseries, etc. | 0.3 | 4,384 |

| Insurance | 0.0 | 8,445 |

| Financial services | 0.4 | −6,704 |

| Other services | 0.3 | 494 |

| Consumption by nonresidents on the economic territory | 0.7 | 7,542 |

| Consumption by residents in the ROW | 0.7 | −7,464 |

| Private hospital services | 0.4 | 538 |

| Private recreational and cultural services | 0.2 | 1,546 |

| Private education | 0.1 | 7,247 |

| Private retirement homes, day-care centres, etc. | 0.3 | 717 |

| Private kindergartens, nurseries, etc. | 0.3 | 116 |

| Other private services | 0.2 | 0 |

Source: Basic input–output data are from Statistics Denmark (2015a).

The fraction shown in the column ‘Consumption impact factor’ is for each sector of consumption or stock change. Together with the impact factor of Table 3.1, it is multiplied by and subtracted from the corresponding activity figure in monetary terms, to give the result shown in the last column, here only for private sector outputs.

Table 3.3

Example of Applying Corrections Due to Resource Depletion and Environmental and Social Impacts to the National Activity Accounts of Denmark for 2011.

| Monetary evaluation of national activities | Consumption impact factor | Public consumption (both production and use impact estimates subtracted) (M DKK) |

| Denmark 2011, public sector | ||

| Food products | 0.3 | 93 |

| Footwear | 0.2 | 8 |

| Maintenance and repair of the dwelling | 0.4 | 38 |

| Furniture and furnishings, carpets and other floor coverings | 0.5 | 26 |

| Household textiles | 0.5 | 43 |

| Domestic services and household services | 0.4 | 322 |

| Pharmaceutical products and other medical products | 0.3 | 2,573 |

| Therapeutic appliances and equipment | 0.3 | 594 |

| Out-patient services | 0.4 | 1,534 |

| Purchase of vehicles | 0.3 | 183 |

| Transport services | 0.4 | −39 |

| Data processing equipment | 0.1 | 13 |

| Appliances, articles and products for personal care | 0.3 | 3 |

| Insurance | 0 | 66 |

| Therapeutic appliances and equipment | 0.3 | 308 |

| Out-patient services | 0.4 | 846 |

| Hospital services | 0.4 | 4,082 |

| Recreational and cultural services | 0.1 | 6,894 |

| Education | 0.1 | 60,346 |

| Retirement homes, day-care centres, etc. | 0.3 | 11,715 |

| Kindergartens, nurseries, etc. | 0.3 | 11,097 |

| General services | 0.2 | 6,692 |

| Defence | 1 | −19,745 |

| Order, safety | 0.2 | 100 |

| Economic affairs | 0.5 | 2,540 |

| Environmental protection | 0.1 | 2,514 |

| Housing, community amenities | 0.4 | 212 |

| Health | 0.4 | 544 |

| Recreation, culture and religion | 0.2 | 2,069 |

| Education | 0.1 | 1,123 |

| Social protection | 0.3 | 2,027 |

| Stock change | ||

| Dwellings | 0.4 | 8,056 |

| Buildings other than dwellings | 0.4 | 2,765 |

| Other structures and land improvements | 0.5 | 13,975 |

| Transport equipment | 0.6 | 4,491 |

| Computer hardware | 0.2 | 5,836 |

| Telecommunication equipment | 0.2 | 510 |

| Other machinery and equipment and weapon systems | 0.6 | −2,752 |

| Cultivated biological resources | 0 | −73 |

| Research and development | 0.1 | 27,676 |

| Mineral exploration and evaluation | 0.4 | −307 |

| Computer software and databases | 0.1 | 18,341 |

| Entertainment, literary or artistic originals and other intellectual property products | 0.1 | 2,892 |

| Valuables | 0 | 2,010 |

| Inventories | 0 | 7,797 |

| Exports (without deductions for negative impacts during use) | 548,106 | |

| Imports (with deductions for negative impacts in production and use) | 371,262 | |

| ‘Green GNP’ (misleading in respect to import/export ratio) | 595,090 | |

| Consumption, stock change and export corrected for national impacts | 966,352 | |

| Total stock change | 91,216 | |

| Total private consumption | 228,210 | |

| Total public consumption | 98,819 | |

Source: Basic input–output data are from Statistics Denmark (2015a).

The fraction shown in the column ‘Consumption impact factor’ is for each sector of consumption or stock change. Together with the impact factor of Table 3.1, it is multiplied by and subtracted from the corresponding activity figure in monetary terms, to give the result shown in the last column, here only for public sector outputs. At the end, imports and exports are summed up, although no consumption impact subtraction can be done for the export values without doing similar studies for the countries receiving the exports. In any case, such impacts should, for consistency, be accounted for by the receiving countries, not by the exporting country.

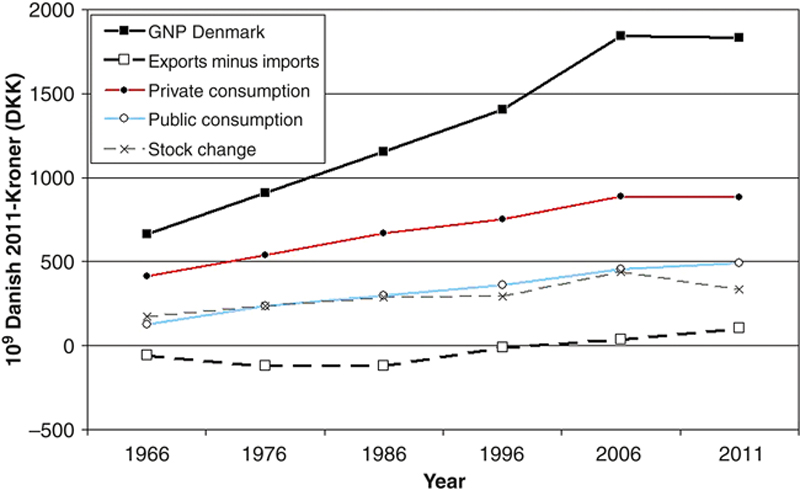

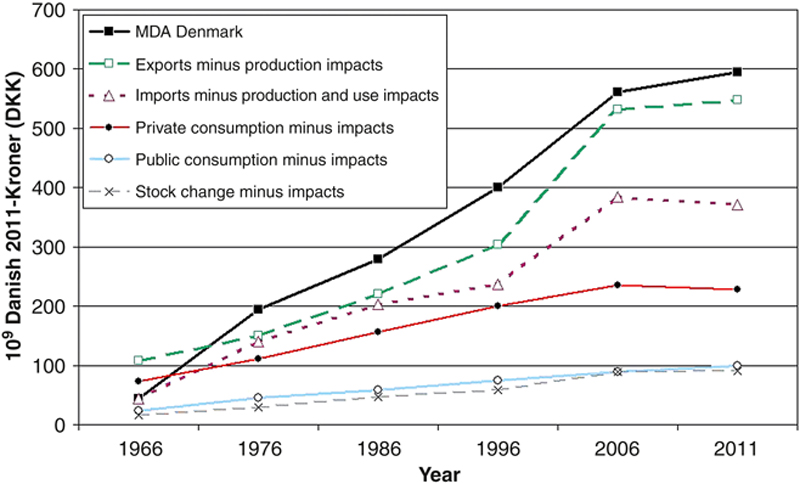

The MDA differs from the GNP by subtracting environmental and social impact costs in production and use, here based on a set of simplistic factors multiplying each activity transaction, as discussed in the text. These factors have been held constant except for the production impact factors of agriculture and electricity production, taking into account the declining use of pesticides and increasing ecological production, and the transition from oil and coal first to natural gas and then toward renewable energy power generation (currently covering about 40% of demand).

3.1.3. A New Look on Wealth and Inequality, Illustrated by a Case Study

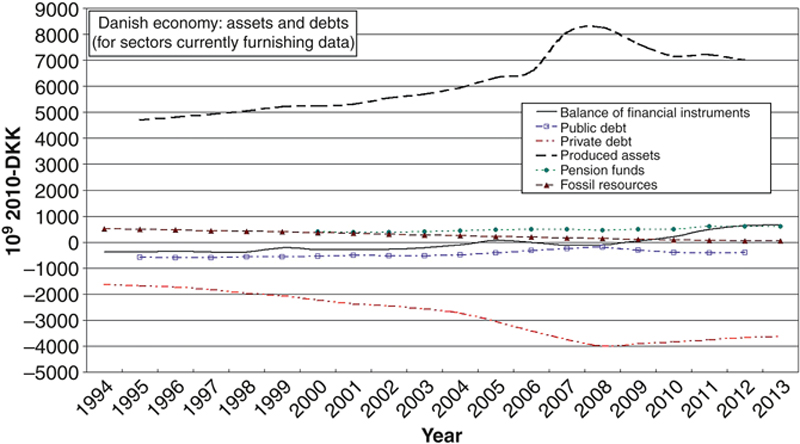

The balance of financial instruments covers all sector of the economy and both domestic and foreign assets and liabilities. The public debt comprises both domestic and international debts, while the private debt includes only domestic loans. The produced assets are detailed in Fig. 3.4. The pension funds are stock and equity holdings of private pension enterprises, as valued for each specific year, and the fossil resources are the sum of market values over the years remaining to depletion (the feasible production has already declined to a value that makes the estimate of extrapolated future extraction rather unimportant). Data sources: Statistics Denmark (2015b; Skat (2015); Danish National Bank (2015).

The dominating values, those of building property, are taken from (currently biannual) taxation assessments (Skat, 2015), comprising all property with buildings (all types of dwellings, industrial, commercial and farm buildings). The value of the plot of land upon which the buildings are erected is included, but not the value of open land, forests, lakes or ocean areas. The remaining tangible assets are valued at purchase price minus depreciation along an assumed average lifetime, and a similar procedure is used for intellectual property (Statistics Denmark, 2015c). Infrastructure includes roads, bridges and railways, while equipment comprises any equipment used in commerce, industry and private households.

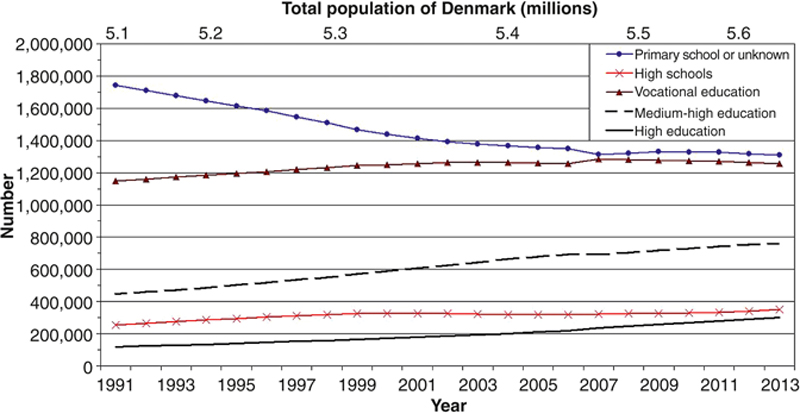

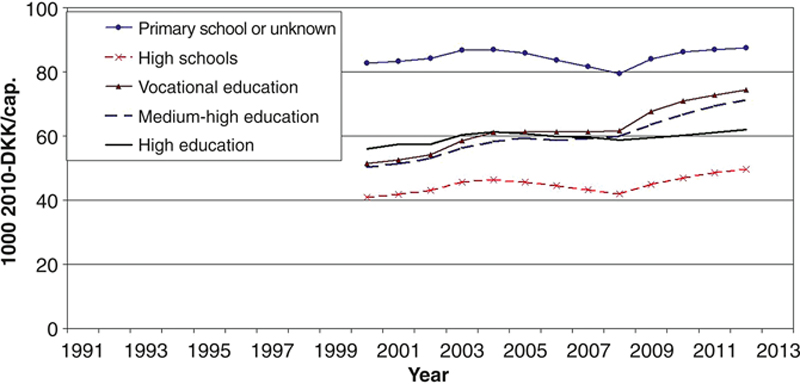

3.1.3.1. Education

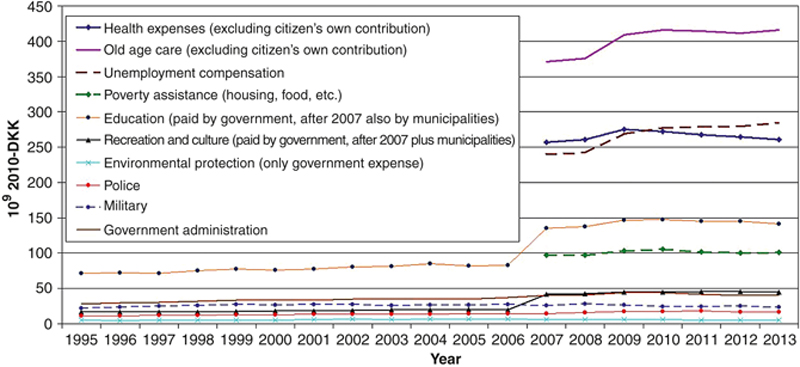

Only persons in the age interval 15–65 are included. Subsidies such as unemployment benefits are included, and their size can be seen in Fig. 3.8. Pensions are not included. Based on Statistics Denmark (2015f).

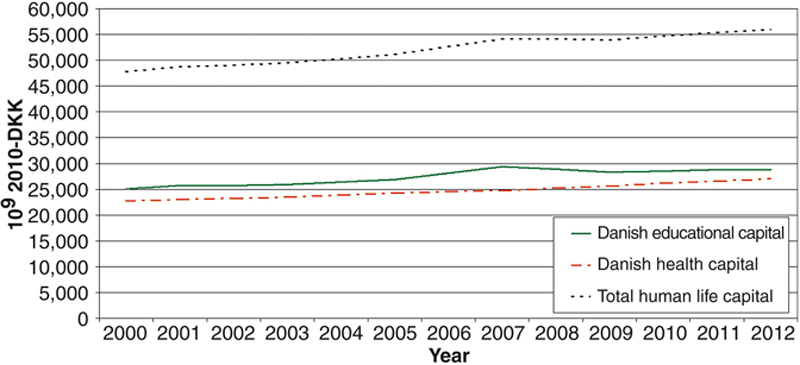

The total life capital is calculated as the sum of values describing the human capacity to service society through work, valued as earnings depending on education, and values of health and longevity extensions by medical and lifestyle advances, in turn permitting social coherence activities and cultural activities such as producing science and knowledge, art and entertainment. Data are derived from the sources of Figs 3.8 and 3.9, as well as from EC (1995) and Sørensen (2011).

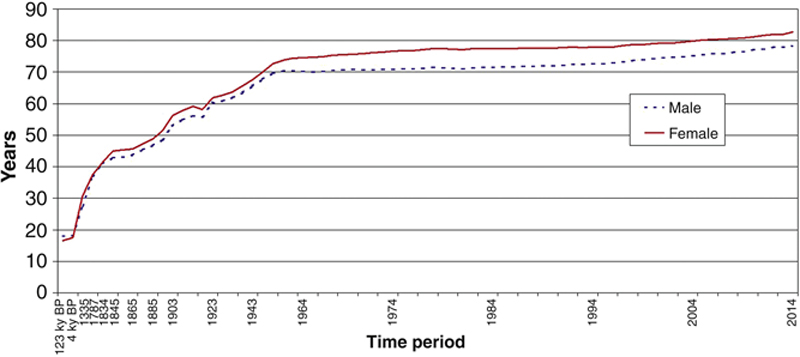

3.1.3.2. Health

3.1.3.3. Adding Up Wealth

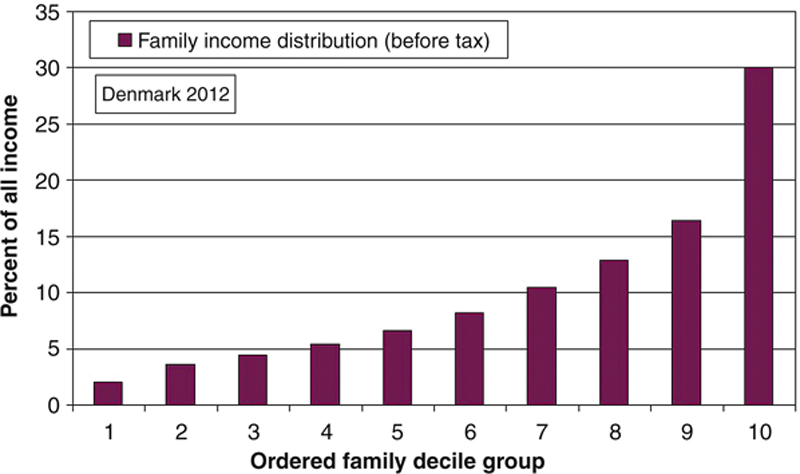

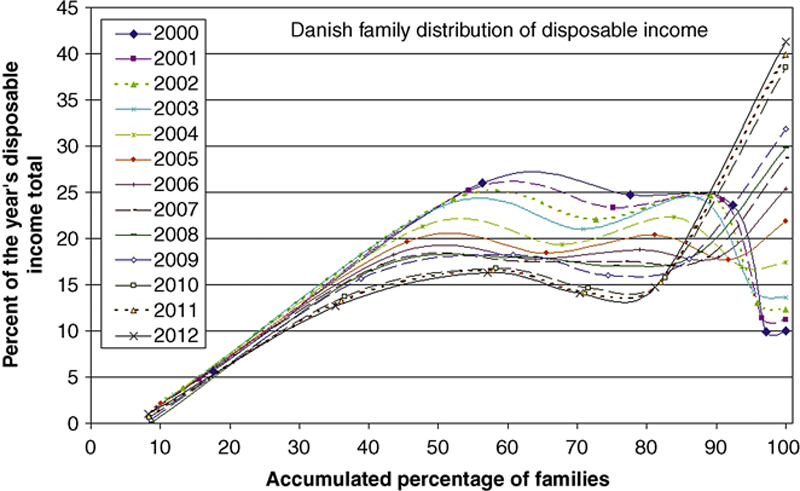

3.1.3.4. Inequality

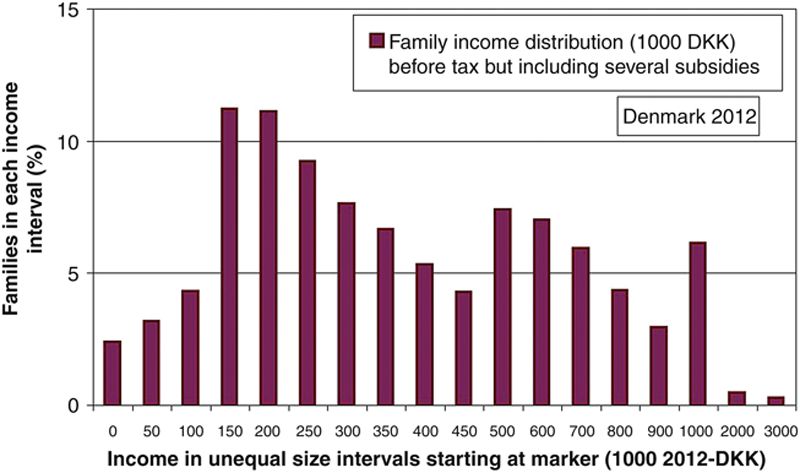

The discontinuities at 500,000 and 1,000,000 DKK are mainly due to the change of scale (Statistics Denmark, 2014).

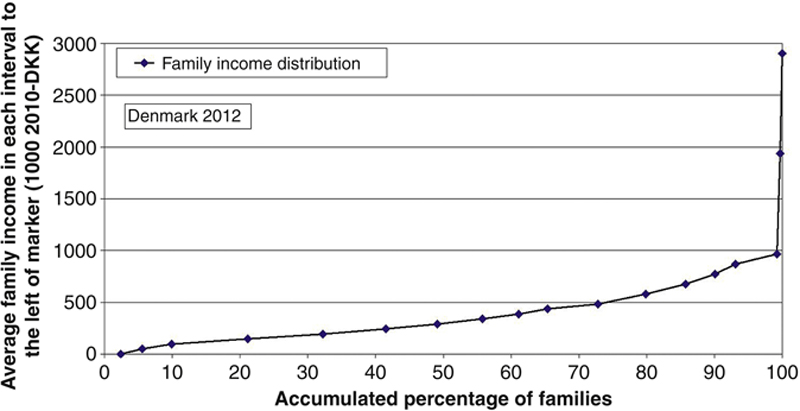

The data points are again not equidistant (Statistics Denmark, 2014).

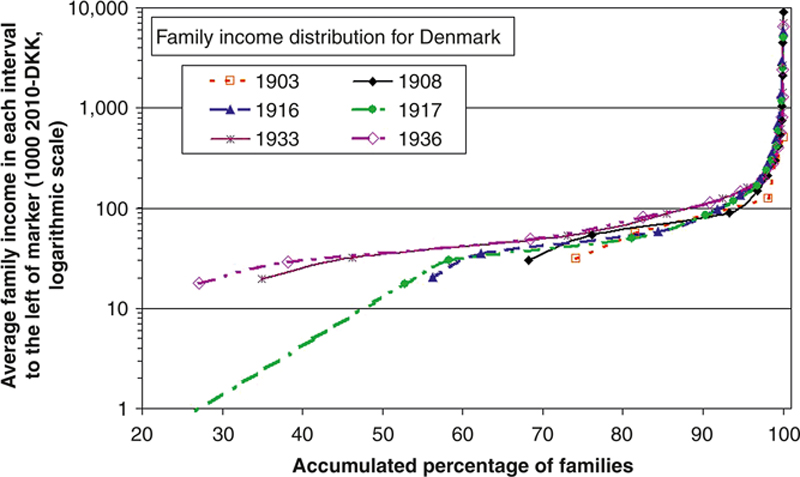

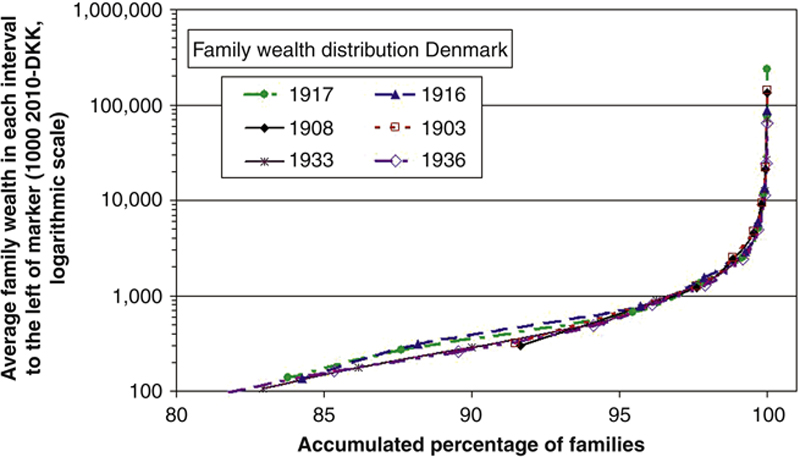

The statistical data collection did not during the period in question consider incomes below 800 DKK (around 40,000 2010-DKK), but Statistics Denmark did try to extrapolate the curve for 1917 downward, using the known number of families with no reported income at all, around 7%. The definition of a family is discussed in the text (Statistics Denmark, 1919, 1938).

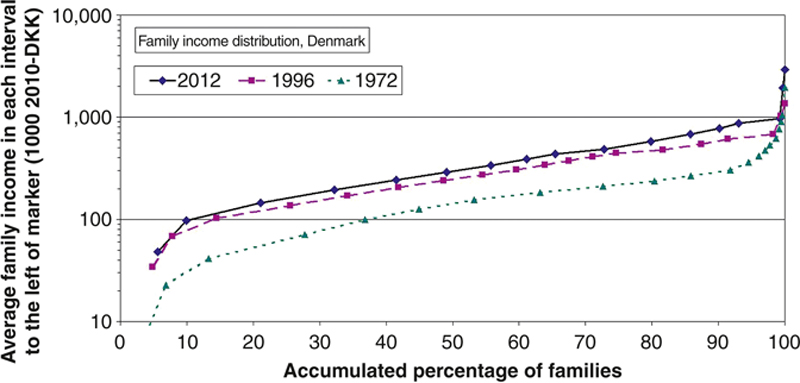

The definition of a family is discussed in the text (Statistics Denmark, 1975, 1998, 2014).

3.1.4. Buying and Selling Goods

3.1.5. Work Versus Meaningful Activities

3.1.6. Tolerance and Multiple Solutions

3.2. How to formulate constitutions

3.2.1. From Ancient Greece to Revolutionary France and Liberal USA

Our constitution does not copy the laws of neighboring states; we are rather a pattern to others than imitators ourselves. Its administration favors the many instead of the few; this is why it is called a democracy. If we look to the laws, they afford equal justice to all in their private differences; if no social standing, advancement in public life falls to reputation for capacity, class considerations not being allowed to interfere with merit; nor again does poverty bar the way, if a man is able to serve the state, he is not hindered by the obscurity of his condition. The freedom, which we enjoy in our government, extends also to our ordinary life. There, far from exercising a jealous surveillance over each other, we do not feel called upon to be angry with our neighbor for doing what he likes, or even to indulge in those injurious looks, which cannot fail to be offensive, although they inflict no positive penalty. But all this ease in our private relations does not make us lawless as citizens. Against this fear is our chief safeguard, teaching us to obey the magistrates and the laws, particularly such as regard the protection of the injured, whether they are actually on the statute book, or belong to that code which, although unwritten, yet cannot be broken without acknowledged disgrace.