Specific Issues and Case Narratives

Abstract

The chapter opens with a discussion of energy efficiency in each sector of current economies. A discussion of lifestyles, revolving around life in a community, development of skills and continued learning and education follows. The role of normative impositions is identified and questions of tolerance and treatment of minorities and minority views are raised. This leads to a discussion of conflict, violence and war, with a historical overview and followed by appraisal of the options for a more peaceful coexistence, focusing on possibly giving the United Nations a greater authority to intervene in conflicts, even within a nation, and notably to restrain the arms industry by banning arm’s trade, between nations and eventually inside nations. A role of economic paradigms based on selfishness in promoting violence is suggested. The chapter then turns to a description of some basic social and economic changes proposed in the past. An important idea is that of a basic income to overcome current fears of unemployment and social exclusion. Other issues raised include the best way to ensure sufficient knowledge in the population, both for performing the tasks needed in society and for participating in the democratic processes of elections and referenda, and of setting up the legal and financial institutions required for societies based on monetary transactions. The chapter ends by mentioning the role of capitalism and the neo-liberal persuasion juxtaposed to a lists of elements from earlier used political dogmas that have been preserved despite changes in economic philosophy, and those yet to be implemented.

Keywords

4.1. Energy efficiency and infrastructure

4.1.1. Buildings and Commerce

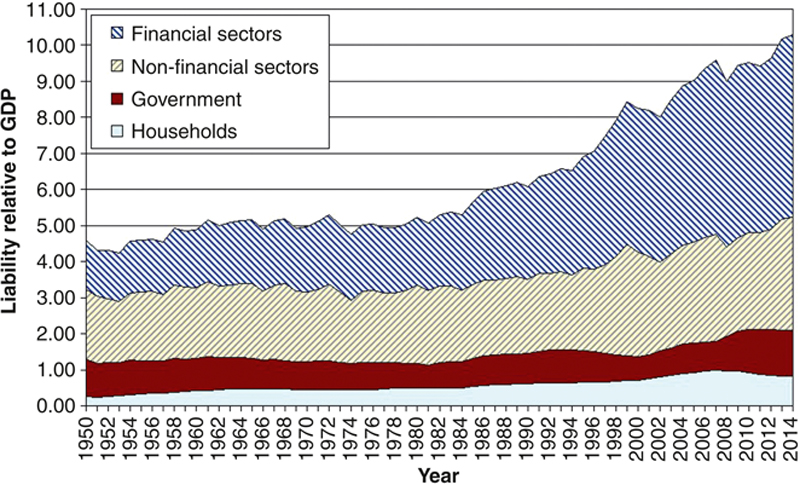

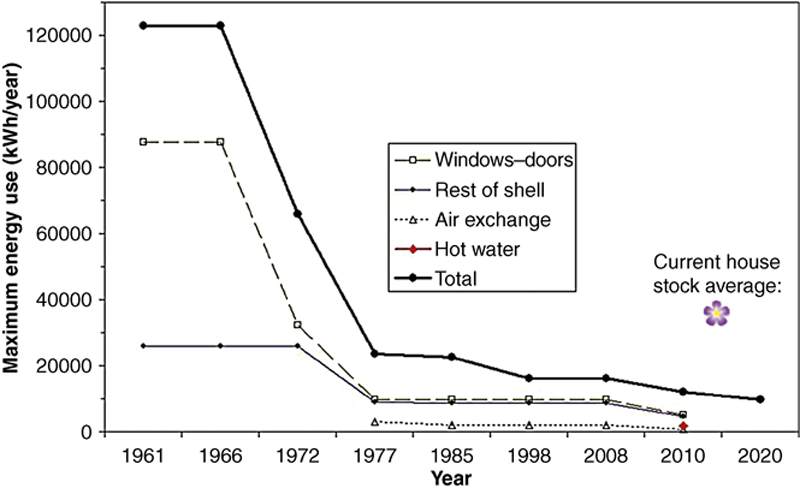

The 1961 building code only considered heat loss through the building shell, but from 1972, also the air exchange was regulated. The 1998 and 2008 code worked with a total energy allowance per unit of floor area, but now for heating, cooling, air exchange and hot water supply together, while from 2010, a range of different rules were brought into play, the overall allowance maintained, but with specific limits for the heat loss through the building shell excluding doors and windows, and specifications for ventilation with required heat recovery and for special heat losses where different building elements come together. Based on Danish Energy Agency (2015), with links to previous building codes. The flower point indicates the average energy use of the present house stock (but for comparison adjusted to 200-m2 floor size, which is higher than the actual average).

4.1.2. Transportation and Services

4.1.3. Manufacture and New Materials Provision

4.2. Lifestyle traits

4.2.1. Living in a Community Thriving on Coherence and Learned Skills

4.2.2. Role of Normative Impositions

4.2.3. Tolerance, Uniformity and Treatment of Minorities

4.2.4. Resolving Conflicts, Abolishing Wars and Cultivating Peace

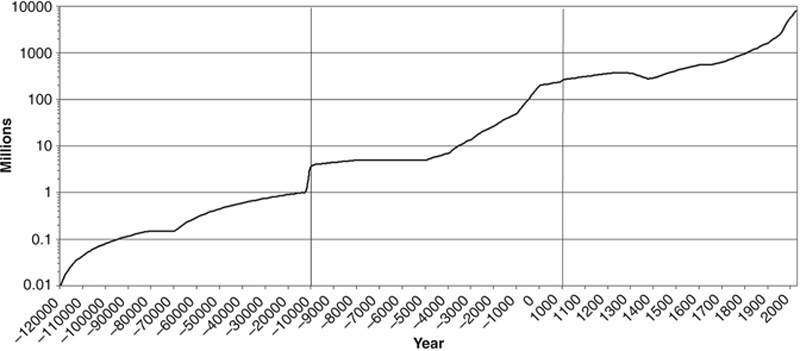

The time scale changes at the vertical lines, from 1000- to 100- to 10-year intervals.

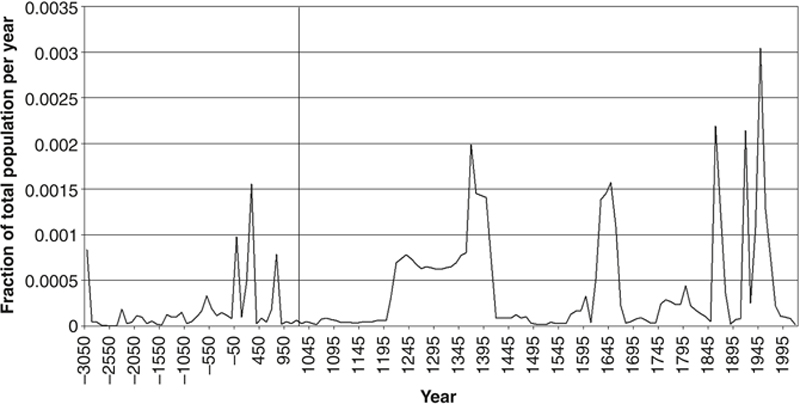

The curve is based on a total of 507 documented war episodes (from Wikipedia, 2015a,b and their references, or based on Kinder and Hilgemann, 1991; using Fig. 4.2 for population data). Unit: ratio between annual deaths averaged over a 10-year period and total world population at the time. The vertical line indicates a change of time scale from 100- to 10-year intervals, this being the spacing between data points plotted.

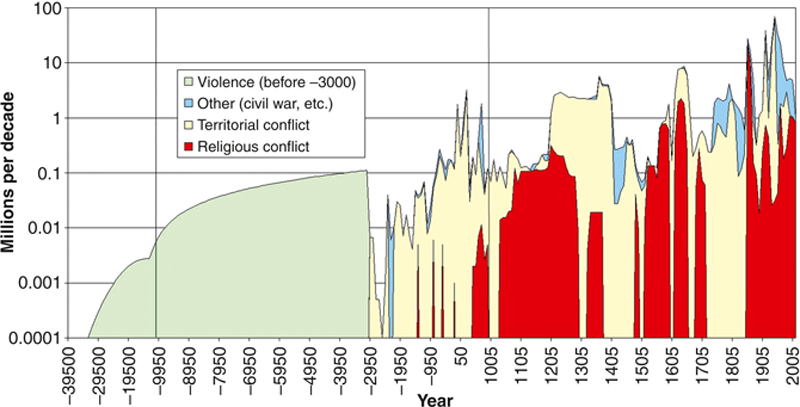

These are stacked with religious causes at bottom, territorial in middle and other causes, such as civil wars, power struggles, etc., at top (from Wikipedia, 2015a,b, or based on Kinder and Hilgemann, 1991). Before the year – 3000, the death tolls by violence in general have been estimated, based on cranial data (Bennike, 1985) and the discussion in Sørensen (2012b). The death toll is given as million victims per decade (note the logarithmic scale), and the time scale changes at the vertical lines, from 1000- to 100- to 10-year intervals.

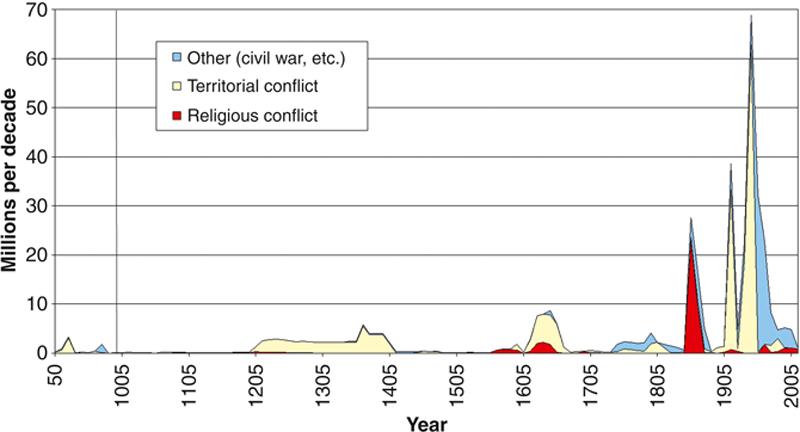

Vertical line indicates change of time scale from 100- to 10-year intervals.

4.3. Selected suggestions from recent times

4.3.1. Basic Income

Table 4.1

Personal Income and Taxation of Adult Danish Population 2013

| Item | Value |

| Personal work and private pension income, not public subsidies | 29,818 |

| Dividends and interest earnings | 1,334 |

| Public transfer incomes | 8,206 |

| Personal tax (on income and wealth, not public transfer incomes) | 10,582 |

| Tax on transfer incomes (taken as 30%) | 2,462 |

| Value added tax (25%) on purchased goods and services | 1,218 |

| Point taxes (on cars, alcohol, tobacco, chocolate, etc.) | 718 |

Source: Based on Statistics Denmark (2015a).

The unit is average €/year per capita (in Aug. 2015, €1 was US $1.096 and 7.45 DKK).

Table 4.2

Constructed Basic Income National Budget for Denmark (with Use of Statistics Denmark, 2015a,b)

| Item | Current value (2014) | New value |

| Average adult personal income a | 33,644 | 27,000 |

| Average personal income taxation a | 11,429 | 11,500 |

| Total taxation (business and private) | 23,801 b | 30,300 |

| Basic income payout (not taxed) | 0 | 8,000 |

| Social protection and adjustments (net) | 11,459 | 8,700 |

| Free education, health, security, etc. | 13,775 | 11,600 |

| Public administration | 4,250 | 2,000 |

The unit is €/year per capita.

a Not including basic income, public transfer incomes and rental value of own property.

b Including tax on goods and services, but not on social transfers. The government finances in 2014 had a deficit of 5776 €/year per cap., while the budget with basic income is in balance. Without balancing, the basic income case would not substantially alter taxation. The balancing expense is here placed as business taxation.

4.3.2. Decentralization, Globalization and Continued Education

4.3.3. Financial and Legal Setup