Making It Work—Operational Details, Tools, Continuous Learning and Adaptation

Why Would Anyone Pay If They Don’t Have to?

The answer is simple: Buyers who do not pay will not get further offers.

This is the first question many people ask on hearing of FairPay—given its superficial similarity to Pay What You Want (PWYW) pricing. But FairPay is very different. It is a repeated game, with a balance of powers—if you want to keep playing you must pay enough to keep the seller satisfied enough to let you do that. With FairPay, there are consequences for not paying—much as there are for having a poor credit rating.

Guiding FairPay Pricing for Control and Predictability

The objective is not just getting them to pay—but getting them to pay enough—in a way that is manageable and predictable enough for a sustainable, ongoing business.

We will look in later chapters at the background on PWYW, and the clear evidence that it is really far more effective and widely applicable than one might think. For now, let’s just take it that most people do pay even when they do not have to, and that PWYW can be very profitable in selected promotional or other special uses, but is often not profitable enough for regular, sustainable use in an ongoing business.

FairPay is very different from conventional PWYW, because it turns it into a repeated game, adding a feedback and control process that give the seller powers over the repeating cycles that fully balance the single-transaction pricing power of the customer.

FairPay turns pricing from a one-time game, in which there is no real penalty for underpricing, to a repeated game. Because of that, customers benefit from continued play, and so are motivated to maintain a good fairness reputation, building social capital at some cost, to retain the option to continue. PWYW—and most other pricing methods—fail to apply this powerful lever to ensuring fair cooperation.

Further, in its detailed operation, this control process can be architected to apply many tools of behavioral economics to nudge customers to pay fairly. As we will explain later, few uses of PWYW have been very sophisticated about framing offers and expectations. Modern marketing methods have huge potential to make such processes work with far greater control and predictability.

FairPay Process Dynamics—The Core Feedback/ Control Cycle

The heart of the FairPay process is the core feedback/control loop that we first saw in Chapter 1. (We repeat Figure 1.1 here, as Figure 7.1, for ease of reference; Figure 7.2 expands on that in a section that follows.)

This feedback/control loop reframes the “pay what you want” element of FairPay, shifting it to “pay what you think fair” (or “fair pay what you want,” which is what inspired the name FairPay)—and enforcing that fairness. As we will see, there are many variations on this basic loop that can be applied, but there is a simple elegance to the balance of forces this loop provides (Figure 7.1).

The key steps of the cycle are:

Gated FairPay Offer, from seller to buyer: FairPay offers are gated by the seller—selectively offered as a privilege, and restricted in value and duration—to limit seller risk.

Accept/Buy/Use, by the buyer: The buyer accepts an offer, buys, and uses a product/service long enough to have a reasonable sense of its value.

Set “fair price,” by the buyer: The buyer is entirely free to set the price (“Fair Pay What You Want”), in his sole discretion, which the seller must accept. (Of course variant forms of FairPay can pre-specify seller-imposed constraints on the price, such as a minimum “floor” price, if that is made clear at the time of the offer.)

Track price: The seller tracks the price set by the buyer, along with relevant context details.

Fair to seller?: The seller decides if they view the price as acceptably “fair,” considering the context.

If so, the seller makes further FairPay offers, continuing the cycle, and extending its benefits commensurately.

If not, the FairPay process ends (possibly after a warning or probation process and a limited number of further cycles), and the buyer is only offered conventional fixed-price sales.

Figure 7.1 FairPay participative process

Here we see the essential difference between FairPay and conventional PWYW offers. Unlike the asymmetric buyer-side power of conventional PWYW offers, with the level of unfairness that often results, the seller has an equal and complementary power to balance that. The buyer knows up-front that FairPay offers are a revocable privilege, and if he does not set the price reasonably, that privilege will end. That is the essence of the repeated game that drives cooperation and equity. Conventional PWYW lacks this feedback/control process—the gating, tracking, and fairness evaluation. PWYW offers are made to anyone, without restriction, so that even those who have a history of free-riding can continue to do so with impunity.

The core balance of these forces is seen in the dialectic of the two arrows:

Price it Backward reflects the buyer’s power and privilege of setting the price after he knows what the product was actually worth to him (unlike the conventional case where the price is set in advance and so there is risk of buyer’s remorse).

Extend it Forward reflects the seller’s power to gate the FairPay offers, and to limit them as a privilege granted only to those who set prices fairly.

This process is participative in that the buyer has real say in the pricing, but the seller still gets to limit his risk. This participative process ensures that both parties continue only if they agree that the prices are fair (at least over a series of cycles). This creates a process of constant learning and adaptation, and the longer this continues, the better the parties understand one another, and the closer the offers and prices get to an ideal win–win value exchange.

Thus FairPay realizes the economic ideal of individually differentiated prices that correspond to the utility and price sensitivity of each buyer in a way that avoids the feeling of unfair “discrimination.” Price discrimination is merely a problem of roles and perception—there is nothing inherently wrong with price discrimination, if it is done transparently and fairly—it is beneficial to the general welfare. Since with FairPay, it is always the buyer who sets the price, the discrimination is inherently acceptable.

This participative nature is what gives FairPay real power to enable a business to build a deep win–win relationship with its customers, to achieve high loyalty and sustainable competitive advantage.

Framing—Expectations of What a Fair Price Should Be

Framing is one of the key methods for making FairPay effective. It is the process of shaping (“framing”) expectations. Framing is the toolbox used to manage how FairPay offers are presented, and what expectations on pricing are set—both up-front and throughout the dialogs on value—to serve as a key technique for managing customer response.

One of the best ways to manage FairPay pricing may be to draw on a suggested pricing structure to frame the setting of FairPay prices to be done by the buyer. Here is an example of how that can work for the seller.

When making the offer, provide a preliminary suggested price schedule, so the buyer has a clear idea of what you will be expecting. The buyer can still be completely free to price as he feels fair, but will know the seller’s reference point.

After usage, provide the buyer with a specific suggested price based on that schedule, and adapted to reflect details of the actual usage. The schedule might be a single price, or might provide whatever level of structure you think the buyer might grasp. The suggested structure might explicitly take into account such factors as usage/volume levels (counts/times, etc.), categories of product/service used (basic or premium, etc.), buyer demographics (business/consumer/student/ retired, etc.), indicators of value obtained, adjustments for any problems, and so on. (This schedule could be customized to the buyer in response to what is learned about him, but showing some information on how it varies, and on how others set their prices can help frame the buyer’s understanding.)

Provide a price-setting form that presents the suggested price and its rationale, and asks the buyer to set a price as the suggested price plus or minus a differential—whether a percentage or a dollar differential. This use of a differential is not essential, but it makes it clearer how the price varies from what was suggested, and facilitates computations of fairness for items regardless of absolute value—for example, a price for a song suggested at $0.99 or an album suggested at $9.99 can each be set buy the buyer as -10 percent (or +10 percent), with essentially the same level of fairness.

Include in the form a set of multiple choice (and optional free text) inputs to enable the buyer to explain the reasons why he thinks his differential is fair. Depending on what is already in the suggested price rationale, these reasons might relate to additional aspects, such as usage/volume, product value perception, buyer circumstances, problems, and so on.

Determine a fairness rating for the price (the differential), as explained by the buyer—unfair, marginally fair, fair, very fair, generous, and so on.

Provide feedback from the seller back to the buyer on the seller’s view, in terms of this fairness rating. (This can be clear and explicit, but can also be left fuzzy, or just implicit in how the offers are made.)

This provides a shared frame of reference that can guide the buyer to price more or less closely to the suggested amount, and provides a basis for communication and judgment as to the fairness of any differential.

This structuring works within the broader FairPay pricing feedback process, in which sellers communicate back to the buyer regarding fairness, and determine whether to make more and better product/service offers, or to warn and restrict the buyer, or to disqualify them from further FairPay offers. That broader process provides the primary method of control:

The seller controls the offer management process to stage their offers to form a series in an ongoing relationship (such as a subscription).

That staging enables the seller to limit the value at risk (at any given stage) to buyers who have not established a reputation for paying fairly, and to extend that as the relationship warrants. Offers can be managed to limit the value of any unfair exceptions, and to minimize their number.

Seller policies can be varied to be strict or lenient, to whatever degree appropriate to a given situation.

With this combination of offer framing, suggested prices, and feedback-driven incentives to price fairly, sellers should generally obtain FairPay prices that average very near to their suggested prices (if the suggested prices are fairly reflective of the actual context of use, as it varies from buyer to buyer, and from time to time).

Of course the idea here is to guide the buyer, but not to be deaf to buyer feedback. FairPay is a dialog about value, and it takes two to have a real dialog. If there is a pattern of buyers pricing below suggested values in any context, that is an indication that buyers are not satisfied with the value received in that context. Such a situation should be understood as a disagreement as to value that the seller needs to address, whether by changing the perceptions of the value, the realities of the value, or the price suggested in exchange for that value.

Keep in mind that this may work best where a conventional set-price offering remains the default for those who do not price “fairly.” I suggest generally pegging the suggested FairPay prices somewhat below the set (non-FairPay) prices to give the effect of a relationship discount to those using FairPay, and thus add to their incentive to maintain that FairPay privilege. That provides a “stick” to enforce fairness, but as we see in the next section, we can also add “carrots” to put a more positive spin on things.

A Richer View of the FairPay Process

Building on that core cycle, we can add important features to make this process more compelling. Perhaps most powerful is to build in a richer incentive structure (with both carrots and sticks), using product/service tiers (Figure 7.2).

First, we start at the bottom with the conventional “Set-Price Zone” in which prices are pre-set by a potential seller as usual. While this might be eliminated in a pure FairPay world, it seems that it might always be desirable to retain this as a fallback for those who do not price fairly, and to maintain a reference price to backstop the FairPay process.

The basic FairPay cycle begins at the lower left, entering what we call the FairPay Zone. FairPay offers can be introduced more or less selectively, to specific buyers, as a special pricing privilege. There, a potential buyer is first presented with a FairPay offer from a potential seller, subject to basic qualification criteria. This could be a known buyer who is viewed as likely to be receptive and fair, or an unknown buyer (prospect) who will be tested in early cycles of the process. The initial offer may be limited to basic services, as the buyer and seller get to know one another with respect to FairPay pricing. The basic principles of the FairPay Zone would be introduced, including how enhanced offers tiers reward fairness and generosity, as we see at step 7.

The buyer can accept the FairPay offer, with the understanding that it is on the basis of Pay What You Think Fair (= Fair Pay What You Want), with the price to be determined after initial use.

The buyer tries the product/service, and learns its actual value to him at that time.

The buyer is then reminded to set his FairPay price for that transaction—to “Price it Backward”—and invited to give any explanation that might be relevant (preferably in multiple choice form). The seller might include a report on usage and suggest an individualized value-based price, to help frame an anchor price. Again the reward of enhanced service tiers is emphasized.

The seller tracks that price and any explanation, and relates it to any prior history for that buyer to determine a FairPay Reputation for the seller.

Now we get to the added layer of enhanced product service tiers. Based on that price and the FairPay Reputation, the seller decides whether to make further offers (now or in the future). This can be done at various levels of granularity—for example, in a simple two tier case:

If the price is considered Low-Fair, basic offers are continued.

If the price is considered High-Fair, offers are continued, and even better premium offers might be extended (including higher value products/services, special perks, more time to try before pricing, etc.). Use of a premium tier gives added incentive for the buyer to pay the maximum he thinks fair.

If the price is considered Un-Fair, the FairPay privileges are (eventually) revoked, and the buyer goes back to the conventional Set-Price Zone (at least for a time). That gives the buyer an incentive to be at least minimally fair. (Such downgrades can be handled gently, such as with a probationary period in which the customer is first warned that more favorable pricing is needed to maintain the FairPay privilege beyond one or a few more probationary cycles.)

Figure 7.2 FairPay process with incentive tiers

Again, this process is generally best applied in combination with conventional set-pricing (as with a paywall). That gives a clear alternative, and clear consequences for not paying at a level the seller can accept to be fair. It establishes a clear reference price to use as an anchor for FairPay pricing considerations (it probably should not be framed as being a minimum price, since there may often be good reasons to pay less, and doing that might make it harder to motivate people to pay more than that without giving them extras). The conventional pricing remains a real alternative for any buyers for whom the FairPay process is ill-suited or unappealing.

This simple approach can take on many forms, and provide great amounts of flexibility and adaptability. (And of course good marketing communications skills should be applied to framing the operation of this choice architecture in the most customer-friendly light.)

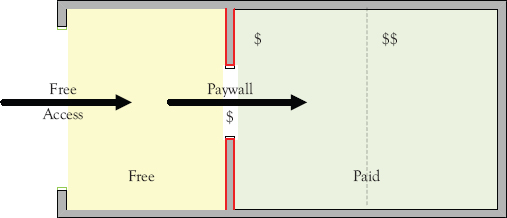

A simpler view of the complementary nature of these strategies is in the following diagrams. First we start with a conventional freemium service, a simple “soft” paywall, with limited free product, and a set-price paywall for usage beyond that (such as for a newspaper subscription). As shown in Figure 7.3, there might be multiple tiers of services, with a higher fixed price for the premium tier (to the right).

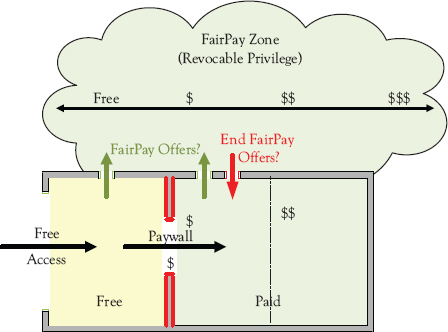

Then we add the FairPay Zone above that (Figure 7.4).

These diagrams hide the details of the FairPay processes, and simply show it as a fuzzy FairPay Zone, with prices running along a spectrum. The idea is that we move beyond a paywall with set prices, to apply a flexible spectrum of prices (vs. products/services) that adapts to whatever the buyer and seller agree to be fair.

Figure 7.3 Conventional paywall

Figure 7.4 Paywall plus FairPay Zone

If this is done with well-considered policies, it will be sustainably win–win. Once a buyer is invited into the FairPay Zone, he will want to retain the privileges that go with that, and will seek to keep the seller satisfied, so that privilege is not revoked. (And when this is not the case for a given buyer, the extent of abuse can be limited.) This balance of forces increasingly converges over time to enable the seller to obtain the maximum price that each participating buyer thinks fair, and thus to maximize revenue over the entire addressable market. That is how FairPay works as a repeated game that is continuously adapted to seek to continue on a win–win basis.

How to Set Policies?—Continuous, Pervasive, Multivariate Marketing Experiments

People often ask about how these policies and parameters should be set, and I answer based on my expectations of what will work in likely contexts, drawn from several years of developing these ideas. This book makes suggestions, but these are only initial presumptions—bound to be revised and enhanced as experience is gained with real customers in real business contexts. Strategies will vary with the industry and business, and from customer segment to segment. They will also vary over time, as both businesses and consumers become familiar with this new logic and how each other behave as they come to better understand it.

Sophisticated marketers will see how this process is well suited to emerging strategies for targeting and testing of offers with multiple variables, and the application of Big Data analysis and predictive analytics. Instead of doing A/B or multivariate testing or similar marketing research as a side activity of limited scope and duration, FairPay builds it into routine processing—into every offer and every price for every transaction (subject to some basic simplifications).

The range of parameters to be considered is summarized in the following points. Some apply to both FairPay and traditional PWYW (and other strategies), and others are more specific to the added processes of FairPay. FairPay is not one specific method, but a general architectural framework. Specific implementations of FairPay can take widely varying forms. We will be looking at some of the most interesting of those variations.

Reviewing the overall perspective outlined earlier, there is a hierarchy of levels to this architecture:

Level 1: Adaptively seeking win–win: The general strategy of setting dynamically personalized pricing—based on adaptively seeking win–win pricing and value propositions, for specific customers in specific time-varying contexts, as understood through a Cloud of Value. It seems that sooner or later this has to become the best basis for a productive economy.

Level 2: The core FairPay cycle (the invisible handshake): The fundamental process for balancing

the power of customers to do post-pricing (price it backward) with

the power of a business to control whether and what further offers are made to each customer (extend it forward?).

This seems the only promising process architecture for achieving Level 1—one that promises to work very well once it is tested and refined—but perhaps other methods will become apparent as we learn more.

Level 3: The particulars: How and where FairPay complements or supplants other pricing techniques, and what specific forms it takes in varying business and market contexts—and how that evolves. Here we can only guess, and time will tell—if we do reasonable experimentation to get from here to there.

Level 1 is clearly the direction for the future. Level 2 promises to be the way to get there—and even if getting Level 2 to work well involves some bends in the road, trying it and learning from it will help us find the path to Level 1.

At the same time, remember that limited negative results at Level 3 should not be taken as conclusive, just as limited success with PWYW does not mean that there is not something to work from there. Given how radically new and unfamiliar these methods are to both businesses and customers, we need a reasonable period for learning—and to raise broader understanding about how these methods can and should work. I expect that important levels of initial success can be achieved with just months of serious and skillful effort—but even if it takes years, it will be worth the journey.

A Flexible, Extensible Architecture

An important aspect of FairPay as an architecture is how flexible and extensible it is. As we will see in Chapter 15, this architecture has many levels and many policy parameters that can be varied. These can be tuned to create a wide spectrum of behaviors, using a variety of choice architectures, relating to such aspects as:

Gating, nudging, warning, dispute-resolution

Up-selling, down-grading

Liberal or tight control

It can coexist with conventional pricing, such as varying what method is used with what segment based on their fairness behaviors. It can also be tuned to behave in ways analogous to conventional methods—but with better personalization—to parallel conventional behaviors relating to:

Freemium and paywalls (metered/soft)

Tiers, segments, and dynamic/usage pricing

Personalized mixes of customer revenue and advertising.

We will also examine a range of strategies for how FairPay can be phased in:

Applying it first to limited, controlled populations in confined aspects of a business, to minimize risk during the initial learning process.

Gradually adding levels of sophistication and control, so customers can become acclimated, and businesses can learn how controls should be developed.

What Kinds of Business Should Consider FairPay?

The following chapters look at representative examples, but at the broadest level, FairPay is applicable to any business that seeks ongoing relationships with customers. It is less well suited to short-lived commercial relationships, since there is no incentive to play the repeated game, and little opportunity to learn how to find a win–win level of fairness with a specific customer.

There are two major modes for selling goods or services that FairPay applies to in slightly different ways (many businesses may include both):

Subscription relationships.

These offer recurring access to ongoing services, and so are an obvious and natural place to apply FairPay. Examples include all kinds of content subscriptions, whether single source, like the New York Times or CBS, or multisource like Netflix or Spotify, and similarly for other kinds of services such as Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, and Dropbox, and more specialized services like Match.com or Yelp. This has been described as “The Subscription Economy” and brings out the full richness of the transition from Goods-Dominant Logic to Service-Dominant Logic. Companies are already realizing that this is a fundamental shift in how they do business, manage operations, and do financial accounting. Subscription commerce refocuses the objective, to not just seek cash from transactions, but to seek renewal. That leads to ongoing revenue streams that can be grown, in terms of frequency, add-ons, usage, and upgrades. That, in turn, leads to much greater revenue opportunity, and involves changes (and ongoing adaptation) in product and pricing strategy, customer subscription management, billing and payments, and analytics.

FairPay cycles map directly to the periodic cycles of subscriptions, with services offered for defined intervals of time, and pricing backward on the experience of each completed interval, and extended forward to additional intervals. FairPay can be used to set prices for each interval as a cycle, or in simplified forms over some number of intervals treated together as a single FairPay pricing cycle.

We will explore subscription uses for journalism (in greatest detail, as exemplary), music, and TV/video.

Discrete item sales (in ongoing relationships, such as by aggregators).

Examples include Amazon, iTunes, and the like, and software app stores, as well as other distributors of music, games, apps, and e-books. (We will also explore non-digital item-oriented uses.)

FairPay can be effective here as well, by managing FairPay offers as relating to bundles of items (as opposed to intervals of access). For example, it could be applied to customer-selected bundles (any desired selection) of 5 or 10 songs, or albums, or e-books, or software apps. The pricing backward is done for each such bundle (with feedback on individual items as desired), and it is then extended forward to offer additional bundles. (More in the next section.)

To summarize likely product/service categories a bit more specifically, these include:

Anything with low marginal cost

Long-tail of content—low-popularity products (expand market/gain revenue)

Short-head of content—high-popularity products (expand market/gain revenue)

Digital content/products/services (by item or by subscription)

News/information/magazines

Video

Music

Games

E-Books

Apps/Software

Other Digital Services

Real products/services (especially experience goods)

Low marginal cost (primary product or extras/support)

Sampling/trials/coupons/promotions (e.g., Groupon)

Perishable excess (e.g., hotels, transport, performances)

Costly goods—with a minimum price floor + FairPay bonus

In general, FairPay is especially well suited where the following apply:

Experience goods/services, which are hard to predict the value of until they are actually experienced by the particular customer.

Items with low marginal cost, where the cost of learning whether a given customer will price fairly is low. This is typical of most digital products/services (those that are not resource-intensive). It also applies to non-digital items that are perishable (like hotel rooms or restaurant seatings) and in cases of special promotions (like a Groupon coupon business).

Costly goods/services are a bit more challenging, but there seems to be interesting potential in setting a minimum “floor” price (paid up-front) to cover variable costs, and then a post-priced bonus to provide a fair profit after the value is fully known (such as for a service like Etsy).

Appreciative customers and “deserving” sellers/creators. Obviously fairness and generosity in pricing will be highest from customers who appreciate what they are getting and feel that the supplier merits their support to sustain that. This gets to the idea of “patronship” as discussed in some of the following examples, such as for journalism and the arts, and for socially conscious companies. And, of course, such an appeal is especially relevant to nonprofit organizations.

Any of these in a secondary line of business—even for businesses in which the primary product/service may not be well suited. These may include product support and ancillary services.

And keep in mind that all of these markets can be served by FairPay as a platform business (Pricing as a Service), with additional leverage and economies of scale, as discussed in Chapter 13.

Item-Oriented Versus Subscription Purchases

As we look at specific industries in the following sections, we encounter a mix of subscription-oriented sales and item-oriented sales. The fundamentals are largely the same, but some details vary. A given business may have some of each. We introduced the case of subscription in Chapter 4—here we complement that with a brief look at item sales.

This could be any kind of item: music, games, news stories, or even physical items. More detail, including aspects related to an aggregator that sells items for many independent providers, is provided for the example of an app store in Chapter 10.

The FairPay process for an item-oriented business (such as an app store) can be quite simple:

The store offers to let buyers try a small number of FairPay-eligible items on a FairPay basis, with the understanding that the buyer can try the items for a time, and then set whatever price they consider fair. The full FairPay process would be explained in detail up-front, so buyers understand that future FairPay offers will depend on what reputation they develop for paying fairly.

The buyer tries the items, then sets prices, and can indicate why they paid what they did. For example, a buyer might explain that they were disappointed in a product if that is why they decided to pay little or nothing for it. (Of course they can also say they love it, or love the band/developer, and want to pay especially well.) A suggested price for each item might be provided for guidance.

The store then assesses the prices paid, and the reasons, and decides whether to offer that buyer more items on the same FairPay basis. Criteria might include consideration of item-specific suggested prices, and the prices set by other FairPay buyers.

Those who pay well will get a continuing stream of further FairPay offers (as long as they continue to pay reasonably well). Those who pay well for some, and explain why not for others, might also get some further offers (effectively on a probationary basis), until it is determined by the store that they either do or do not pay fairly—whether for particular product categories, or in general.

Those judged by the store to generally not pay at an acceptable level can be cut off from further FairPay offers (in general, or by category), and restricted to conventional, set-price sales (at least for some time, possibly extending a second chance to try FairPay sometime in the future).

The cycle continues, based on these evolving FairPay reputations. The longer this process runs, the more meaningful the FairPay fairness reputations of the buyers, and the better able the store and developers are to manage revenue and risk, by controlling what offers are made to which buyers.

Behavioral Engineering, Choice Architectures, and Dialogs About Value

Here is a brief summary of the key principles. Later chapters expand on how this applies in specific industries, and review the behavioral economics and game theory principles of why and how this can be effective.

FairPay provides an adaptive learning engine that enables each customer to find a pricing style that works for him and for the seller. Customers who adapt to this new dynamic can find a new freedom to get what they want at a price that they agree is fair. Those who value the product and have willingness and ability to pay will be offered the world. Those who see less value and are willing and able to pay less will still get most of what they want, again at a price they agree is fair. Those who repeatedly refuse to pay fairly enough to satisfy the seller will get cut off from FairPay offers. (They may instead be given the option to buy at the full set price.)

FairPay sellers build real relationships with individual customers in which the customer feels understood and respected. These “dialogs about value” focus on the value of the product, the service, and larger social values that matter to the customer. Sellers who convince customers that they not only produce good products, but are also good partners and good corporate citizens, can draw on communal norms of behavior to entice generous “premium” pricing,

Sellers might restrict the FairPay offers that they extend to new customers who lack established FairPay reputations. They might even restrict them to items and quantities that would otherwise be free trials (much as with freemium pricing), so that their risk is small. Only after the customer establishes a history of paying fairly will the seller continue to make FairPay offers for larger quantities or more premium items. The benefits to the customer of not paying will be limited and short-lived. The benefits of paying fairly will continue and grow.

Sellers can be expected to make these consequences clear when they first extend an offer to sell on a FairPay basis. The product/service is not offered as “free,” nor as simple PWYW, but as Fair PWYW, or perhaps better put as Pay What You Think Fair—essentially on trial, on approval, and on evaluation. Sellers would make it clear that zero is “acceptable” (with regard to reputation and future consequences) only if that is arguably fair. Such cases of reasonable fairness in setting a zero price might include cases in which the customer gives a reason why there is little or no realized value to the customer (much as is often required for returns)—or where only very low quantities are sampled (which might be accepted as a customer-directed form of free sampling).

Game-Based Marketing and Loyalty Programs

One potentially important level of sophistication in choice architectures that is only touched on here is gamification. Given the nature of FairPay as a repeated game, adding elements to more directly gamify the customer journey might be very popular and effective for some customers. Such methods have become a popular tool in varied aspects of e-commerce and loyalty programs.

Well-designed choice architectures are essential to managing FairPay—to encourage open and frank dialogs about value, and to help motivate generous pricing. Some customers can be stimulated by adding explicit gamification elements that offer recognition and competitive status, such as points, levels, badges, challenges and rewards. These can be focused within relationships with individual customers, or can create open competition among customers who gain status relative to other customers on leaderboards or by getting other visible rewards such as badges that signify their generosity and cooperative engagement.

FairPay pricing of loyalty program rewards in the currency of miles or points is also an important opportunity, and an interesting place to consider early trials. Current loyalty programs for credit card usage, travel services like airline mileage programs, and for other services often provide points that can be redeemed for rewards. Why not allow reward prices in points to be set using FairPay? What better way to enhance the loyalty of your best customers by extending them that special FairPay privilege?

Transparency, “Trust but Verify,” and Context

The quest for win–win is a fundamental change of mindset from the zerosum mentality that pervades much of modern commerce. Businesses are very secretive as to their pricing strategies, how they discriminate and segment markets, what their costs are, what their profit margins are, and the why of all that. Consumers play the counter game of seeking bargains and trading “intelligence” (strategies, discount codes, and the like). We even seek ombudsmen to balance the most extreme power inequities—the New York Times has a column called “The Haggler,” that champions abused consumers.

For the cooperative dialog of FairPay to be effective in creating win– win relationships, we must shift toward levels of transparency and trust that push the boundaries of current commercial relationships. That may cause fear and loathing for businesses more used to trying to put things over on their customers and feeling that customers cannot be trusted. (I am reminded of the War Room scene in Dr. Strangelove, as the Soviet ambassador enters.) Later chapters dig into these issues of customer-hostile value propositions and the behavioral economic and psychological principles behind FairPay, but for now, some brief comments.

On transparency, companies are realizing that they do better when customers trust them to provide real value and not play deceitful games against them. Mobile phone and cable TV companies are pulling back from notorious extremes of customer-hostility. Apparel company Everlane is extolling its transparency about sourcing, costs, and profits. FairPay builds on these directions to make co-creation of value a more truly cooperative effort.

On trust, people question how customers can be trusted to set fair prices and not lie in their dialogs about value. Here the idea of “trust but verify” is relevant. As noted earlier, Big Data about how customers use products and services is providing very rich data about consumption and implicit metrics of value (a Cloud of Value). It will be increasingly easy to validate what customers say in their dialogs about value against the hard data on what they actually did. If you quit a book or a song a short time into it, that would support a claim that you did not find it valuable. If you read a book through in successive long sittings, or played a song 20 times in a month, such a claim would clearly be very dubious.

Price Discrimination Can Be Good!

Transparency can enhance the viability of dynamic pricing and the more win–win forms of price discrimination applied in FairPay. (Some interesting references are at FPZLink.)

Dynamic pricing is theoretically optimal, but has been perceived as inequitable in consumer markets, and price discrimination is almost a dirty word (actually illegal in some situations). Amazon experimented with price discrimination in its early days, and backed off after negative reactions, but there are occasional reports that other vendors discriminate by location. Uber’s “surge-pricing” policies have now made this a hot topic again.

The real problem is one that can largely be fixed in a “postmodern” economy. The problem with dynamic pricing is that it is set unilaterally by the seller, and imposed on the customer on a “take it or leave it” basis (if not hidden completely). But, still, discrimination is economically optimal. That is why it is widely used in the hotel, airline, and car rental businesses. In those industries customers have learned to live with it—but still with considerable resentment. The way to make price discrimination acceptable to customers is to involve them in the pricing decision.

That is one of the key features of FairPay. Applying FairPay’s longterm relationship view, customers have significant participation in pricing, and can be asked by sellers to include a dynamic premium if it is for good reason—but they can decide just how extreme that premium should be. Sellers get to determine if the customer is generally being fair about that, and continue to allow FairPay pricing in the future to those who are.

Remember, it is abundance, not scarcity, that FairPay thrives on. The more tractable form of discrimination is when the premium is not to ration scarce supply, but to ration share of wallet where replication is free—to reflect cases where a customer gets higher value or has higher ability to pay. It is much harder to justify being indignant about unfairness in such cases, especially when it is tied to contributing a fair share toward sustaining creation of new services that are valued.

Another factor in customer acceptance is predictability. This is really a problem of unpleasant surprises, and price changes that seem unfair. The perceived unfairness of dynamic prices and discrimination, such as with the Uber’s New Year’s surge, or for snow shovels or flashlights after a storm, is the “unfair” external imposition of higher prices. Here again, when the customer gets to opt in to the level of dynamic premium, that changes it to a fair and equitable process.

Which brings us back to transparency. Transparency leads to a deeper level of consumer understanding that makes it easier to justify price discrepancies that might otherwise seem unfair. What if one customer talks to another and learns he has gotten a very different price for an item?

FairPay increases both transparency and context-dependency. If two customers find that they have very different prices for “similar” content under FairPay, such as for music, it will become apparent that they are comparing different amounts of usage, at different times, different genre mixes, different levels of advertising, different levels of playlist control, different ability to pay, different satisfaction levels, and many other disparities in usage context and value (and sellers can highlight such factors).

It will be apparent that they are comparing apples and oranges, and that a higher price corresponds to higher value received, which is justified and fair—and that the customer has agreed to that without being a chump.

Thus “discrimination” can be good—when done within reason, at agreedupon levels, based on mutually understood reasons.