CHAPTER 7

Operational Analysis and Post-Implementation Reviews

Don’t stop thinking about tomorrow, don’t stop, it will soon be here. Don’t stop thinking about tomorrow, yesterday’s gone, yesterday’s gone.

—FLEETWOOD MAC, “DON’T STOP,” 1977

The active management of an investment portfolio requires knowledge gained through monitoring and evaluating its various constituent investments. It is essential that financial investors not lose track of how their investments are performing. This does not diminish the importance of looking for potential new investments, but the importance of the current portfolio should be regarded because it is the present basis for wealth creation and investment success.

This same reason for analyzing the performance of a current financial portfolio—to assess its capacity to achieve investment goals—also holds true for IT portfolios. An agency’s ITIRB must periodically review and evaluate the performance of the agency’s current set of IT portfolio assets. All current investments must be periodically scrutinized so that the ITIRB can be fully informed about how well the investments are performing.

OMB states that the management-in-use phase of the investment life cycle begins after a system is developed or acquired and implemented and is usually the longest phase of the investment life cycle.1

Because operations and maintenance activities often account for more than 80 percent of total life cycle costs, OMB requires agencies to continuously monitor the capital asset inventory to ensure that investments have the right size, cost, and condition to contribute to and support the agency mission. Consequently, as part of the CPIC process, the ITIRB should require that routine operational analyses of in-use assets be conducted. The key objectives of such reviews are to:

![]() Demonstrate that in-use investments are meeting agency needs and are delivering expected value

Demonstrate that in-use investments are meeting agency needs and are delivering expected value

![]() Determine if the investments need to be modernized or replaced

Determine if the investments need to be modernized or replaced

![]() Identify smarter and more cost-effective methods for delivering performance and value

Identify smarter and more cost-effective methods for delivering performance and value

What Is an Operational Analysis?

An operational analysis is a formal review of an asset’s performance. The reviews conducted during the CPIC process focus on IT assets. Depending on how long the asset has been operational, the scope of the review can include both current performance and anticipated future needs. The ultimate objective of an operational analysis is to be able to make one of three basic recommendations:

![]() The investment is performing as expected and therefore should remain in the operations and maintenance phase of its life cycle.

The investment is performing as expected and therefore should remain in the operations and maintenance phase of its life cycle.

![]() The investment needs to be enhanced to improve its performance and therefore should shift into a mixed life cycle, combining operations, maintenance, and enhancements.

The investment needs to be enhanced to improve its performance and therefore should shift into a mixed life cycle, combining operations, maintenance, and enhancements.

![]() The investment has serious performance deficiencies and should be modernized.

The investment has serious performance deficiencies and should be modernized.

An operational analysis is likely to result in any number of recommended actions, but an asset’s future status should be determined based on the results of this formal review.

At a minimum, an operational analysis compares the actual results to the cost, schedule, and performance goals established in the planning phase. It is also a means for identifying gaps or inconsistencies between the technology the asset employs and the organization’s current and target enterprise architecture, as well as determining if the asset can meet current and future business needs as envisioned in the organization’s strategic and annual plans. The analysis can also be used to evaluate user satisfaction.

Beyond identifying gaps in performance, an operational analysis also determines the cause of any identified gaps between actual performance and initial goals and provides a foundation for analyzing alternative solutions. For example, if the asset is not meeting its performance goals, the magnitude and causes of the gaps should be included within the scope of the review. Various courses of action should be identified and analyzed so that the review results in meaningful action to address performance problems. If the operational analysis uncovers problems in the planning and control phases of a single asset, it may also find systemic problems in the organization’s overall CPIC procedures.

To be successful, the operations review must be seen as a positive activity by everyone in the agency—one that is designed to assess and potentially improve an asset. It is an unbiased, clinical review of how the asset is performing, as well as an assessment of its ability to meet future needs. The review must be portrayed as an unvarnished assessment of investment performance. It is not intended to identify past problems or to “point fingers.” The tone for the review can be established through executive leadership awareness and support, the careful selection of review team members, and the development of an operations review plan that identifies potential sources of bias and techniques to address them.

Which Assets Should Be Reviewed?

An agency needs a global approach to operational analysis and reviews that reflects the agency’s operating environment, asset mix, evolving business needs, and other operational factors. For example, an agency that depends on legacy systems and a mainframe environment will likely take a different approach to operational analysis than an organization that uses newer technology and operating platforms. While both agencies should conduct an operational analysis of their assets, their approach, timing, and scope will likely differ.

In general, reviews are conducted on a cyclical basis, and all operational assets are candidates for a review. Ideally, each asset should be reviewed within a 24-month timeframe. This is a simple, consistent approach, but it can also lead to the perception that operations reviews are simply paperwork exercises.

Another approach is to target those investments commonly acknowledged to have the most potential for identifying issues because they use older technology, their users are not happy with their performance, or for some other compelling reason. By minimizing the perception that operational analysis is a paperwork exercise, this approach generally provides the greatest potential for improving portfolio performance.

The following is a partial list of investment characteristics that should be considered when scheduling reviews:

![]() Legacy systems supporting critical business functions

Legacy systems supporting critical business functions

![]() Systems in production for less than two years

Systems in production for less than two years

![]() Systems that have the potential to be consolidated and/or outsourced

Systems that have the potential to be consolidated and/or outsourced

![]() Infrastructure systems

Infrastructure systems

![]() Systems that rely on architecture that is not part of the target enterprise architecture

Systems that rely on architecture that is not part of the target enterprise architecture

![]() Systems that are scheduled for a major enhancement or refurbishment

Systems that are scheduled for a major enhancement or refurbishment

It is not necessary to review each asset independently. In some cases, it might make sense to combine reviews because a group of assets are related or because they face similar issues. For example, conducting an operational review of all telecommunications infrastructure would be appropriate if the organization was facing a major strategic decision regarding the implementation of new technology or protocols. An integrated enterprise resource planning (ERP) system would likely be reviewed in its entirety, even though it might consist of multiple components (e.g., financial management components, procurement components), because decisions regarding ERP implementation and future use cannot be made at the component or application level.

An ERP system is an umbrella framework for a set of applications that support a broad set of organizational activities and operations. Modules might include planning, acquisition and purchasing, inventory management, supplier management, customer service management, and case/order tracking. These modules are generally fully integrated with financial and human resources management applications.

Who Should Be on the Operations Review Team?

Selecting team members is a critical aspect of the operations review process. Selecting the wrong people may waste time and also undermine the independence and objectivity necessary to conduct a credible review. In a results-based world where the performance of every aspect of agency operations is already scored, tracked, color-coded, and published, agencies are unlikely to have an environment supportive of yet another scoring activity. The review team must deal with measurement fatigue and other forms of resistance, and the team must gain acceptance from a wide group of stakeholders.

One approach that ensures objectivity is to use an outside team, such as staff from another office within the agency, CPIC team members who have experience with operational analysis, or contractors. An outside team can bring independence and objectivity because it generally does not have a hidden agenda and is better able to call things as it sees them. But such teams may not be familiar with or understand the investment, the history of its development, and its strategic importance to the agency’s business needs and mission. While it’s possible to learn about the investment’s background and gain an understanding of its value during the planning phase of the operations review, the knowledge of external reviewers will always be less than that of those who are involved with the asset on a day-to-day basis.

A second approach is to establish a review team of investment owners and users who are assisted by technical staff. This team has a better understanding of the business needs the asset was designed to meet, as well as an understanding of the asset’s development and operations history. It also has a deeper understanding of the system’s goals. The drawback is that these team members may have biases that could inhibit the rigor of the review. Users and owners generally give substantial input during the planning, design, and development life cycle phases, and therefore they may be less inclined to report performance problems or other issues later on.

A third approach is to use a combination of team members—some who interact with the asset on a regular basis and others who do not. The team members who interact with the asset can provide expertise regarding business needs and development history, which may help explain the causes of any performance issues. The team members who don’t work with the asset can provide needed objectivity and perspective, and they can also offer knowledge and expertise about newer technologies and alternative approaches to achieve investment objectives.

Regardless of the review team’s composition, team members who have actively developed or participated in procurement of the system should not have an active role in the operations review. Instead, the review team should interview and otherwise interact with those development/procurement personnel to gain the information and insight needed. This ensures that the operational analysis results are objective, and it enables decision makers to rely on analysis results and recommendations.

What Should Be Reviewed?

The purpose of performing an operational analysis is to determine how assets are performing and to take actions to address any issues or deficiencies. Operational analysis results can also be used as input to the planning process, to identify future performance or operational issues.

Each analysis is tailored to address issues involving the target investment because the status, history, business needs, and operating and support environment are likely to vary significantly from asset to asset.

While each review is unique and should be adapted to the specific asset at hand, the following four dimensions should be included:

![]() Performance assessment: Is the asset meeting its performance goals?

Performance assessment: Is the asset meeting its performance goals?

![]() Cost assessment: Is the asset significantly under or over cost projections?

Cost assessment: Is the asset significantly under or over cost projections?

![]() Technology assessment: Is the asset in compliance with the organization’s target enterprise architecture?

Technology assessment: Is the asset in compliance with the organization’s target enterprise architecture?

![]() Security and privacy assessment: Does the asset meet all security and privacy requirements?

Security and privacy assessment: Does the asset meet all security and privacy requirements?

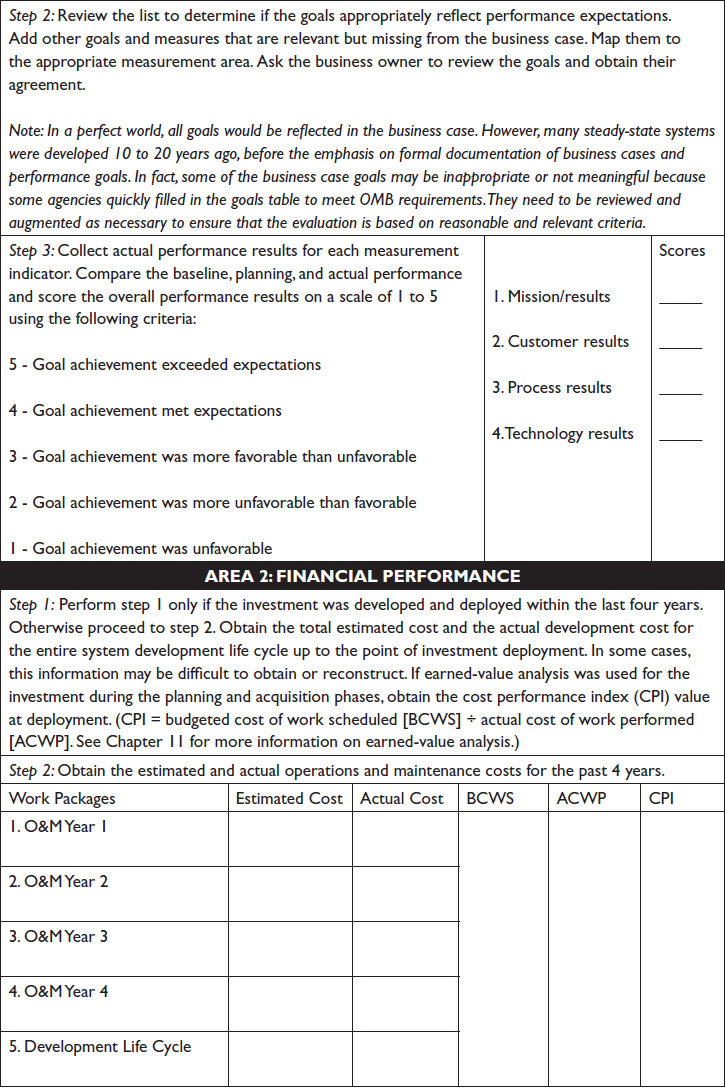

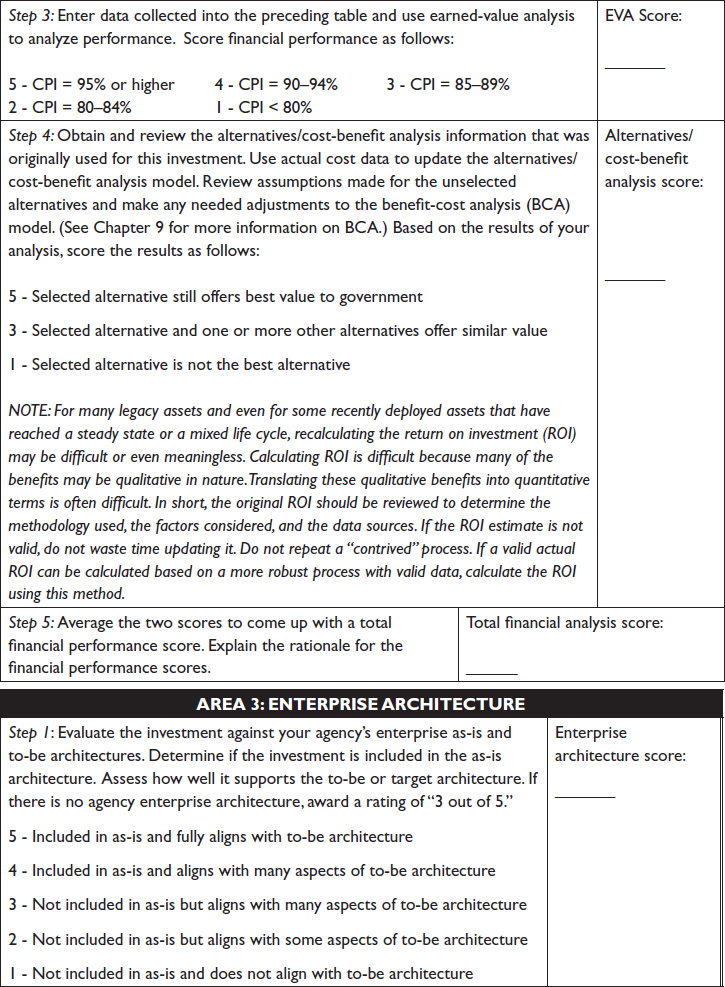

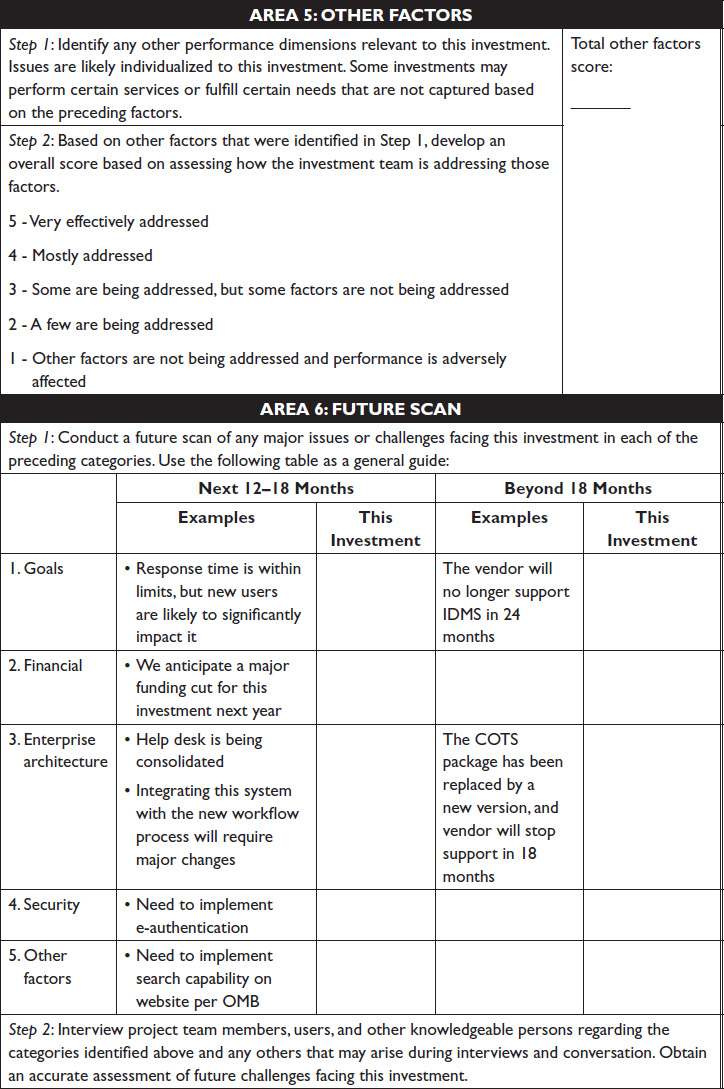

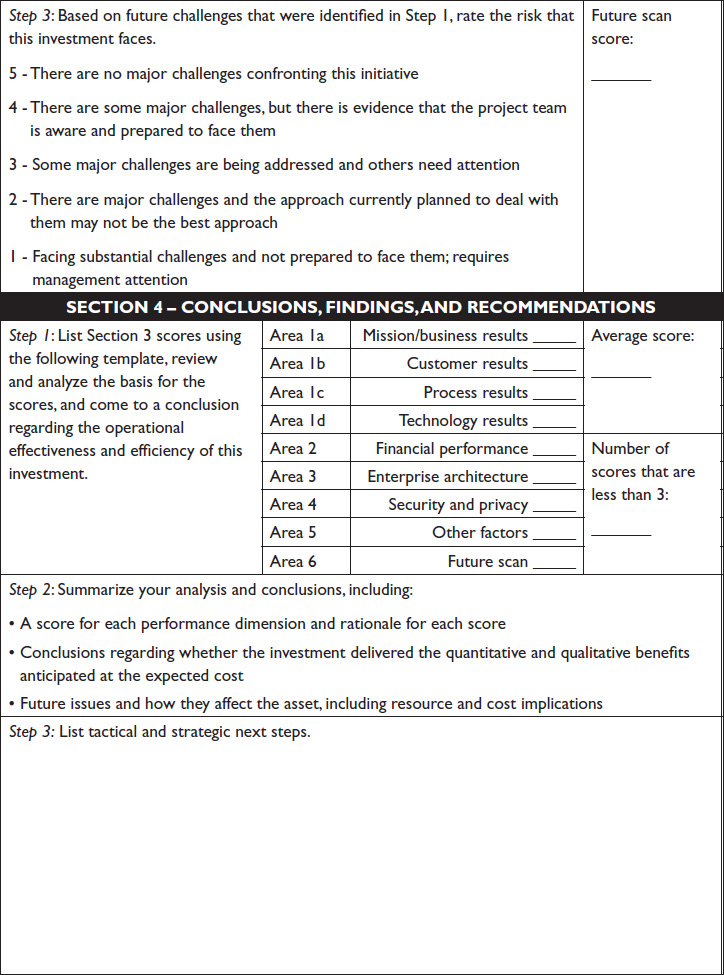

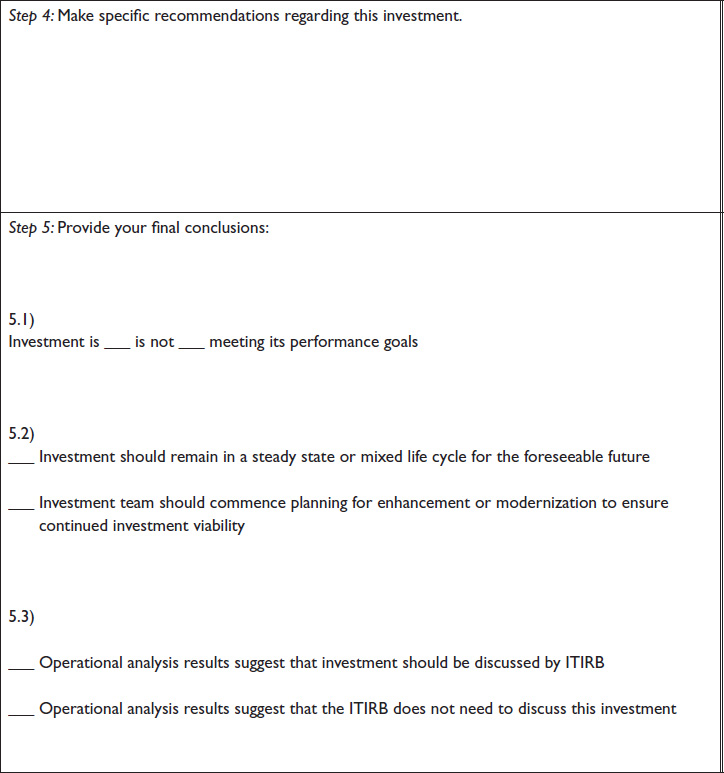

Table 7-1, at the end of this chapter, provides a sample operational analysis worksheet.

Performance Assessment

The performance assessment analyzes progress in meeting the goals established in four primary areas: mission and business, customer results, processes, and technology. Legacy systems may not have explicit, documented goals with performance baselines and targets. In most cases, however, implicit goals and expectations will exist, and formal goals are likely available from the investment business case.

The review team must validate existing goals, measures, and performance expectations to ensure that they are meaningful and useful. In some cases the team may have to synthesize the goals and measures if the ones that exist do not capture the desired performance characteristics or if no goals exist at all. Many agencies were not fully prepared to develop performance measures and targets when OMB implemented its Exhibit 300 business case requirements. Performance measures were simply part of “filling out necessary paperwork” and therefore may not fully reflect legitimate agency and user expectations. A key benefit of an operations analysis is to review and potentially strengthen the performance framework within which investments operate and are reviewed.

Cost Assessment

In analyzing the asset cost, the team should compare actual versus planned cost for maintenance and enhancements. While it is difficult to gauge operations and maintenance costs before a system has been developed or acquired, once the activities begin to happen, operations and maintenance forecasts should be revisited and, if necessary, revised or updated. Modifying the baseline is an acceptable practice as long as the ITIRB and other investment stakeholders are informed and their permission is obtained. Consequently, the operations analysis will compare fairly recent estimates of operations and maintenance costs against actual cost data.

According to OMB, the overwhelming cost of IT software accrues after it is implemented. The team must therefore scrutinize the cost-benefit analysis, substituting actual data in place of estimates, to determine if anticipated return on investment (ROI) was achieved. In some cases, legacy systems may not have an existing cost-benefit analysis. The agency’s EVM system provides the key information needed to analyze cost performance by comparing the budgeted cost of work scheduled to the actual cost of work performed. The cost performance index must also be analyzed. To determine if the anticipated ROI was achieved, the same methodology for developing the initial cost-benefit analysis is used, assuming it was a valid assessment.

The review focuses on either the cause of significant cost variances or why anticipated benefits have not been achieved. Some cost overruns can be attributed to new business requirements stemming from changes in legislation. Others are associated with the need to correct errors in the code or to improve existing features. In analyzing the benefits, the review focuses on why benefits have not been achieved and what actions are necessary to achieve the planned ROI. The assessment also documents qualitative benefits and links those benefits back to the business needs and mission of the organization.

Analyzing cost performance offers two major benefits. First, for the specific asset under review, gaining an understanding of the true total cost of ownership early in the asset’s life cycle provides an opportunity to correct problems earlier, saving money and improving quality. Second, by looking across the results of operations analyses of individual assets, systemic cost issues that affect all projects can be identified, which can lead to improvements to the overall approach to managing IT assets.

Technology Assessment

The technology assessment identifies gaps between the technology used to build and support the asset and the technology outlined in the organization’s target (“to be”) architecture. Recently deployed assets are unlikely to have gaps unless an exception was approved for a compelling business reason during the planning process. Legacy systems, however, may not comply with the agency’s enterprise architecture. The operational analysis provides an opportunity to analyze the consequences of noncompliance, including potential cost, support, and integration issues. The remaining useful life of the asset must be analyzed for its ability to meet current and future business requirements.

One example of how a technology assessment was useful to an investment manager involves a mobile health survey unit. Mobile trailers were used to travel from community to community to provide free medical checkups and as a means of collecting public-health data. The trailers were equipped with personal computers and coaxial cable local area network (LAN) connections. When the operational analysis was conducted, it was clear that the frequent movement of the trailers caused wear and tear on the technology and that newer technology, such as wireless connections, was available. These factors were included within the scope of the operational analysis to determine how well the existing technology suited the needs of the agency and program.

Security and Privacy Assessment

Security and privacy goals and capabilities are also included in an operational analysis because of increasing security threats and the need to improve IT protection. The review is not a substitute for a review mandated by the Federal Information Security Management Act of 2002 (FISMA)2 or a privacy assessment. Instead, documentation from these other separate reviews serves as input to the operational analysis. For example, outstanding issues from the latest mandatory FISMA certification and accreditation review should be obtained and examined to determine if sufficient actions have been taken, or are planned, to address deficiencies. Security requirements should also be assessed to determine if additional actions and funds are needed to meet future requirements.

Other Factors

In addition to the four performance dimensions described above, the scope of the review should also capture any particular issues relative to the individual asset under review. These issues may include integration with other systems, how well the investment supports a reengineered business process, need for improved or enhanced training, suitability for decentralized locations, integration with newer technologies (such as handheld and wireless devices), and so forth. In many cases, those familiar with an investment know about design weaknesses and can ensure that long-standing issues are identified and addressed.

Future Scans

The primary purpose of the operational analysis is to assess how the asset is currently performing. It also provides an excellent opportunity for asset planning. By conducting a future scan of major issues or challenges facing the investment, the project management team can better plan for future requirements and expenditures. For example, the asset may be performing well when compared to existing goals, but potential changes to program or business requirements necessitate repositioning the asset to meet them. Similarly, the asset may be in compliance with the organization’s current enterprise architecture, but it may not comply with the target architecture. An operational analysis is a useful tool for identifying such issues and providing additional value-added insight into future management challenges or opportunities, which allows business owners and project managers to plan better.

Conducting an Operational Analysis

After the operations review team is established, the operational analysis is conducted in four phases: planning, data collection, data analysis, and reporting.

Planning

During the planning phase, the nature and scope of the work should be developed, documented, agreed to, and approved by the review team and the ITIRB. This step helps ensure that there is agreement about the areas to be covered, including issues that will be emphasized. A planning template can be used as a starting point to set the scope of the review, identify the review issues, and lay out the basic steps and timetable; however, it will need to be tailored to address the specific needs of each review. The plan must address the four main performance dimensions described above (performance, cost, technology, and security and privacy) and provide for a future scan of anticipated events that may affect the life or operation of the asset.

A formal, written plan for the review should document the scope and approach of the review. It does not have to be an extensive document laying out in great detail every anticipated step in the process. Instead, it provides a framework to communicate to the review team the scope and nature of the review; the overall approach for identifying, obtaining, and analyzing the data; a schedule for completing the review; and an outline of the topics that will be included in the report. The role of each team member should also be defined in the plan.

Data Collection

After the plan is developed and agreed upon, the operations review team can collect and analyze the data. The review team schedules an opening meeting with business owners, users, IT developers and support staff, and representatives from the CPIC, IT security, CFO, and acquisition offices. During the meeting, the review team describes the purpose of the review, the overall approach, and the anticipated timetable. The team also responds to questions and concerns. A summary of the opening meeting’s results is documented and circulated to meeting participants.

After the opening meeting, the team gathers documentation that it plans to review. Basic documentation includes:

![]() OMB Exhibit 300 business cases

OMB Exhibit 300 business cases

![]() EVM data

EVM data

![]() Strategic plan

Strategic plan

![]() Annual plan

Annual plan

![]() Enterprise architecture documentation

Enterprise architecture documentation

![]() FISMA reports, including the most recent certification and accreditation review and the associated plan of actions and milestones (POAAM)

FISMA reports, including the most recent certification and accreditation review and the associated plan of actions and milestones (POAAM)

![]() Project status reports

Project status reports

![]() Any other related materials

Any other related materials

Interviews are then scheduled with key business owners, users, development and support staff, and security administration staff. The team may also meet with a representative from the CFO’s office to discuss cost issues, and with the acquisition staff to discuss any related contractual issues.

In addition to interviews, the team may also conduct focus-group sessions or administer surveys to get a broader view of how an asset is performing and to identify future issues to feed the planning process. The costs and benefits of employing these techniques will drive the team’s decision regarding their use. The skill mix of the team may also limit their use.

Data Analysis

Data are analyzed as they are obtained. When issues that require additional data or perspectives are identified, actions are taken to obtain them. This iterative process provides the basis for developing formal findings and conclusions. Findings must be supported by sufficient, reliable data. The team must identify not only the existence of problems or deficiencies but also the cause and effect of those deficiencies. The cause-and-effect relationships form the basis for analyzing alternatives and making recommendations to senior management.

Reporting

After the fieldwork is complete, the results of the review are documented. The report captures the results and becomes part of the investment’s documentation library. It must be written so that it communicates the review’s scope, approach, methodology, and results, including all findings, conclusions, and recommendations. It is a factual document that should be easy to understand. After the report is drafted, a closeout meeting is held to discuss the results with all interested and affected parties.

The length of the review will vary with the scope and complexity of the asset. In general, most review teams of up to five persons should complete the review within six weeks. This assumes that team members are able to devote at least half of their time to the review.

Outcomes of an Operational Analysis

The operational analysis provides recommendations about the continued use of the asset. Generally the operations review team will make one or a combination of the following recommendations:

![]() Continue with planned operations and maintenance

Continue with planned operations and maintenance

![]() Continue with enhancements

Continue with enhancements

![]() Replace the asset in-house

Replace the asset in-house

![]() Outsource the asset to another agency or a private vendor

Outsource the asset to another agency or a private vendor

![]() Retire the asset without replacement

Retire the asset without replacement

The ITIRB may elect to accept the findings and recommendations or to take another course of action. If an operational asset is designated for enhancement or modernization, a business case for doing so will be required and must include a recasting of alternatives and cost-benefit analysis, summary of life cycle spending, performance expectations, and work breakdown structure with revised cost and schedule estimates.

The review should therefore describe how its recommendations will affect the following:

![]() Achievement of the anticipated return on investment

Achievement of the anticipated return on investment

![]() Performance relative to established performance goals

Performance relative to established performance goals

![]() Performance relative to planned costs

Performance relative to planned costs

![]() Compliance with the organization’s enterprise architecture

Compliance with the organization’s enterprise architecture

![]() Progress in addressing security and privacy issues

Progress in addressing security and privacy issues

In describing identified operational problems, the report should also highlight any systemic problems that were identified and which may have an impact on other agency investments. This enables an assessment regarding any needed changes to the CPIC process that might avoid recurrence of such issues in the future.

Taking Action

The most important result of an operational analysis is the action taken by senior management in response to the recommendations. Assuming that management accepts the results, a specific timetable and plan of action must be developed to identify responsibilities, tasks, a management process, and follow-up actions. The actions must align with the timing of the CPIC planning process. For example, if the asset is to be replaced, a new business case must be developed and approved to coincide with the CPIC planning and selection phases to obtain approval and funding.

If management does not accept the report findings or does not agree with the recommended actions, additional work is needed to resolve the issues causing the conflict. The team may be asked to review an issue or alternative in more detail and present its results. Ultimately any operational problems identified during the assessment will need to be resolved.

Post-Implementation Reviews

A post-implementation review (PIR) is similar to an operational analysis, but instead of examining an asset that has been in operation for several years, a PIR examines the performance of a new asset that has recently been implemented. A PIR typically occurs within the first six months of implementation. The PIR evaluates the project’s success, including how well it met its objectives and addressed requirements, and it identifies lessons learned from the project that might be applied to other projects in the future.

Factors that are examined as part of the PIR typically include:

![]() Alignment with project objectives and requirements

Alignment with project objectives and requirements

![]() Availability of required functionality

Availability of required functionality

![]() Completeness of documentation

Completeness of documentation

![]() Customer satisfaction with support services

Customer satisfaction with support services

![]() Type and severity of identified faults

Type and severity of identified faults

![]() Data integrity and system reliability and performance

Data integrity and system reliability and performance

![]() Adequacy of system controls

Adequacy of system controls

![]() Lessons learned during development and acquisition

Lessons learned during development and acquisition

Because the investment is newly implemented, evaluating customer perceptions and satisfaction is essential. It is also important to identify issues that arose during the project that could have been avoided with the CPIC selection and control processes.

The ITIRB should be advised about the degree to which its decision to proceed with the investment was successful. Information should also be provided regarding how this investment fits with other investments in the portfolio.

Like an operational analysis, an independent team should conduct the PIR. The PIR team collects and reviews documentation, interviews key players, collects and evaluates system performance information, and surveys customers and stakeholders. The team analyzes the results, writes and issues a report describing how well the newly implemented system is performing, and provides any recommendations for improving the investment. The report also recommends any changes to the project management process based on lessons learned during the project.

Table 7-1 ![]() Sample Operational Analysis Worksheet

Sample Operational Analysis Worksheet

ENDNOTES

1. Office of Management and Budget, “Capital Programming Guide—A Supplement to Office of Management and Budget Circular A-11, Part 7: Planning, Budgeting, and Acquisition of Capital Assets,” Version 2.0, June 2006. Online at http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/circulars/a11/current_year/part7.pdf (accessed December 2007).

2. Federal Information Security Management Act of 2002 (FISMA), U.S. Public Law 107-347, December 17, 2002. Online at http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getdoc.cgi?dbname=107_cong_public_laws&docid=f:publ347.107.pdf (accessed December 2007).