CHAPTER 14

Measuring, Monitoring, and Evaluating Portfolio Performance

From the moment I picked up your book until I laid it down, I was convulsed with laughter. Some day I intend to read it.

—GROUCHO MARX, COMEDIAN

The early chapters of this book described the CPIC process. Later chapters focused on specialized analytical approaches used in CPIC to select the best alternatives for achieving investment objectives; identifying and evaluating risk as a basis for making adjustments to the project schedule and budget; and planning, measuring, and controlling work activities. Many federal officials can attest that they follow similar processes and use similar analytical techniques but still face considerable risk that their agencies’ investments will fail more often than they succeed—and that the agencies’ portfolios, as a whole, do not provide the desired level of performance.

Successful investment management takes more than procedures and methodologies. It also requires certain intangible factors—factors that separate those agencies that are very good at investment management from those that are not so good. This concluding chapter looks at those factors.

Critical Success Factors

Agencies face substantial challenges as they implement and improve the effectiveness of the CPIC process. The following critical success factors summarize major elements discussed in earlier chapters that will increase the likelihood that CPIC will achieve its full potential.

Factor 1: The Right People with the Right Skills and the Right Attitude

CPIC works best with full commitment from the agency head and executive management team. They recognize that IT is a mission-enabler and that those who are most responsible for achieving the agency’s mission must determine how it is used. Consequently, some of the most talented senior managers accept appointment to the ITIRB and fulfill their responsibilities vigorously and seriously. They are able to apply their executive talents to the IT decision-making process, and they bring a special talent for focusing on things that merit attention and not diverting significant time and effort to lesser issues. They also understand the importance of calling on the right people and seeking second and third opinions on critical matters. One useful technique is to ask the CFO’s views about a particular investment or investment strategy.

Over the years a number of CPIC implementation successes have occurred because people who understood the benefits of the process and the need for a rational approach to resource allocation have become engaged in the process. For example, a senior official at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) who was responsible for managing a large agency-wide investment was able to provide effective governance by recognizing the need for the investment, understanding the NIH culture, persuading other administrators and scientists to support and participate in the initiative, and tackling problems and challenges as they arose. Another senior IT manager at the U.S. Secret Service advanced CPIC principles within his agency by communicating, advocating, and leading its implementation and refinement.

In short, the talents and capabilities of those involved in CPIC, the involvement of those who have substantial influence at the highest levels of the agency, and the interest of both groups in ensuring that IT assets align with and support mission achievement are critical to CPIC success. Agencies can easily assess their current situation to determine if this critical success factor is present.

Factor 2: Centralized Control over IT Spending

If IT funding is included in the budgets of individual programs, it renders the ITIRB merely a rubber stamp because program managers can basically state that they have the funding to proceed with the investment regardless of what other programs or the ITIRB thinks about its cost, risk, or return. All IT funds must be controlled and allocated by the ITIRB to give the CPIC process the authority and power that is necessary to change past practices and to allocate funds using investment management principles.

From a budget and financial management perspective, supporting this practice is relatively straightforward because the budget is already managed using object and sub-object classification codes that can easily be aligned with the IT oversight function. After the ITIRB decides how to allocate the funds, normal budget execution practices can be followed.

As part of its authority, the ITIRB must have the power to suspend and even cancel investments. These are critical decision tools that are necessary to effectively manage the investment portfolio.

Factor 3: Fully Embracing Investment and Portfolio Management Principles

To keep their eyes on the ball, participants in the CPIC process should be reminded frequently of the underlying CPIC principle—that managing an IT portfolio is like managing an equities portfolio. They must therefore understand and fully embrace investment and portfolio management principles.

Just as an equities investor would do when working with a financial planner, the ITIRB must discuss and establish investment goals for the overall IT portfolio. In this sense, the ITIRB is the agency’s investment broker. It should consult with the agency’s chief architect regarding EA principles in setting the investment goals. The information presented in Chapter 6 on portfolio analysis is useful. Goals can involve ensuring that the portfolio is functionally balanced, that its risk does not increase above a certain level, that investments provide at least a 1:1 benefit-cost ratio, and that they provide some benefit in terms of agency outcomes.

Once goals are established, the ITIRB then uses strategies to ensure that the IT portfolio (or portfolios, if there are multiples) achieves the goal and meets or exceeds expected performance. The CPIC planning, selection, control, and evaluation processes are designed to carry out these activities.

Factor 4: IT People Who Sell Investments

One of the most important critical success factors for CPIC success involves “winning over” the IT people. The CIO bears major responsibility for achieving this cultural adjustment. Initial IT reaction to the CPIC process is generally negative, but if investment principles are fully explained and if project teams are permitted sufficient time and resources to participate, IT officers and staff will eventually understand and appreciate their roles. From an equities investment perspective, project teams are marketing investments and looking for investors. Understanding that this is now a critical part of the IT role can fuel the competitive drive and generate enthusiasm for engaging in the CPIC process.

Factor 5: The Integrity of the CPIC Process

One of the most important changes that many federal agencies still need to make is to ensure that information developed for the ITIRB is not “gamed.” The data might be gamed if funding is still controlled by users, decisions have already been made, and CPIC is simply seen as a pro forma activity that has to be endured. They might be gamed because insufficient time is available to do market research and fully examine available alternatives, or because involved parties are disinterested and do not wish to expend energy identifying outcomes for IT investments or conducting real-world risk assessments and risk-adjusting the project budget and schedule.

But senior officials must depend on having objective and accurate investment information if they are to weigh tradeoffs and make fact-based decisions. Efforts to delude or deceive investors should not be tolerated, for they undermine the entire CPIC process.

Factor 6: A Strategic Enterprise Perspective

The ITIRB must serve as the strategic visionary for agency IT investment. To maximize return on investment, decisions must be made in the interest of the agency and its mission, not on the basis of the parochial needs of a particular business unit or program.

Enterprise architecture (EA) provides a useful tool for monitoring strategic priorities and making individual investment decisions within the broader agency context. Results of portfolio analysis also provide useful information and insight. Together, EA and portfolio analysis present a vision for the future, a transition strategy for achieving the vision, and an assessment of how well the current portfolio is positioned to support the strategic direction. The ITIRB must have sufficient information to make key decisions that are in the best interests of the agency.

Regardless of the source, the ITIRB must proactively manage IT investments using a strategic perspective. The needs of the whole agency and its mission must dominate discussions and decision-making.

Factor 7: Success Determined through Measurement

There is only one true way that an agency can evaluate the performance of its IT assets—through performance measurement.

Chapter 6 discussed the role that EVM plays in providing a comprehensive work breakdown structure, and Chapter 7 discussed the process for having the WBS independently reviewed to ensure the schedule is reasonable. Certainly, EVM is a form of performance measurement. It provides information that enables the ITIRB to monitor and control the performance of the IT project team. EVM is a behavioral measurement tool.

But EVM does not provide information about the performance of the IT asset once it begins to perform its intended duties and responsibilities. We cannot tell from EVM information if the IT system made it faster to process a claim or a case, whether citizens can locate federal information more quickly, or if weather can be predicted more accurately.

At the end of the day, however, we invest in IT to do just that—speed up a claim, find information faster, and predict storms that could wreak damage—and much more. The goal of CPIC is to make a federal agency and its programs more efficient and effective. For this reason, embracing performance measurement as a part of the CPIC process provides the ultimate form of accountability. It enables the ITIRB to look back on its decisions, to understand its own performance in developing the investment, and to evaluate whether the asset actually had an impact on agency efficiency and effectiveness.

Developing outcome and output performance measures is not easy, especially for IT specialists who have not previously engaged in measurement design. Often it is the investment sponsors, the users who will benefit once the system is deployed, who are in the best position to measure investment benefits and identify what data are available for doing so.

It is the responsibility of the ITIRB to review proposed performance measures when an investment is first presented for approval, and to factor them into the decision-making process. Recall that decisions must take into account cost, benefits, and risk, and many of the benefits identified through output and outcome performance measures might not have been included in the quantitative cost-benefit analysis.

Challenge Questions

As we have worked with agencies and individuals over the years, we have often been asked difficult questions about specific topics. Some of those questions, and our responses, are presented below. While some agencies may disagree with the responses and prefer to take a different approach, these responses provide our perspectives and we hope they will stimulate other questions.

Challenge Question 1:

I’m the CIO of a large federal department with many diverse, independent bureaus that receive funding for IT projects directly in their budgets. This situation is not likely to change during my tenure. How can CPIC have any meaning under this scenario? Right now we are simply going through the motions, with our ITIRB affirming decisions that are already made in the program areas.

Response:

CPIC can still be useful in this scenario. It would be unwise to attempt to strip each bureau of its CPIC responsibilities simply because they have diverse missions and IT investments. The objective is to foster increased adoption of CPIC methods and to use mature CPIC processes as a springboard for managing the department-level EA and conducting department-wide portfolio analyses.

To leverage department capabilities, the department can audit each bureau’s CPIC process to evaluate its effectiveness and determine what it will take to implement consistent approaches among all bureaus. It can also develop policies and procedures to foster department-wide consideration of common mission and goal elements.

Challenge Question 2:

Our senior managers do not get involved in the CPIC process, nor do they want to. Their lack of leadership undermines the process, especially with program managers. What is a CIO to do?

Response:

Senior management’s lack of involvement and leadership within the CPIC process is a serious problem. The leadership of an organization sets the tone for how serious the process will be taken by program managers and staff. As the CIO, you should have a seat at the table within the circle of executive leadership. You need to leverage your position to find out why senior management is not championing the CPIC process. Consider the following questions:

![]() Are they new to the federal government?

Are they new to the federal government?

![]() Do they not understand their responsibilities?

Do they not understand their responsibilities?

![]() Do they not appreciate the need for their leadership in this area?

Do they not appreciate the need for their leadership in this area?

![]() Do they understand the risks and consequences of ignoring their role?

Do they understand the risks and consequences of ignoring their role?

![]() Is the CPIC process in your agency so overly complicated, bureaucratic, and technocratic that the leadership sees CPIC as a low-level management duty?

Is the CPIC process in your agency so overly complicated, bureaucratic, and technocratic that the leadership sees CPIC as a low-level management duty?

These are just of few of the many reasons why senior management may not be involved. As the CIO, you need to probe these issues and then take appropriate action based on the cause. If you can’t persuade them to take a more active role, then you either have to live with the status quo until there is a change in leadership or move on yourself.

Challenge Question 3:

Security costs are supposed to be included in all IT investments. How does one determine the separate costs of including security? Isn’t this allocation arbitrary and meaningless?

Response:

Often, when program managers are asked to describe the security of their IT investments, they refer to access security, physical security, disaster recovery plans, and other types of general controls. But the security controls discussed in a business case are the safeguards developed for that specific application. For example, are controls built in to regulate access to various types of data? Are there controls to regulate the modification of data? Are there controls to regulate users’ ability to execute certain commands based on their access level? These are just a few examples of application-level security. Security costs also include the cost to certify the system.

But in reality, application-level security is often an afterthought. Therefore the ITIRB and OMB want to ensure that security is designed and built into the system. The costs of providing security can be estimated just as with the cost of fulfilling any other requirement of the system. Note that it is an estimate, not an exact figure. The objective is to plan security into the process, not to develop an exact cost.

Challenge Question 4:

Congress just passed legislation that mandates a massive expansion of one of our programs. The only way to support the change and meet the mandatory deadlines established in the legislation is to enhance our existing system. Why should we do an alternatives and cost-benefit analysis for a federally mandated project? Time is of the essence. We need to get moving on requirements, design, and implementation, so why should we waste time with a CBA?

Response:

Alternative approaches for enhancing the existing system should be considered. The alternative technical approaches could include changing monolithic code that already exists, creating a separate module to perform the new functions and using it when needed, or creating a web-services capability.

Other alternatives include outsourcing the work, doing it with in-house staff, or using a hybrid approach. Yet another set of alternatives might involve phased implementation, all-at-once implementation, or a hybrid approach. The point is that CPIC fosters careful analysis, within the appropriate context, of innovative approaches that maximize return while minimizing cost and risk.

Even though the time necessary for analyzing alternatives might get in the way of immediately commencing with what is deemed the intuitively correct alternative, spending a reasonable amount of time considering approaches and quantifying costs and benefits can be useful. It provides an opportunity to consider the changes that need to be made and ways to implement those changes, and it avoids a potentially incorrect strategy that might be pursued by rushing into implementation.

Challenge Question 5:

EVM implementation has been a joke in our agency. The program managers do not understand EVM, nor do their contractors. The work breakdown structure is at such a high level that the percent complete is meaningless—garbage in and garbage out. How do we fix this?

Response:

EVM can be intimidating, especially when it is first introduced. However, most people catch on after the concepts and mechanics have been explained to them. If your program managers do not understand EVM, you should hold a training session geared to that audience. Reinforce the concepts by having a tutorial accessible on your website. Remind your program staff that EVM is mandatory for all federal agencies. If your contractors do not understand EVM, you unfortunately have hired the wrong contractors. Federal acquisition regulations were amended in July 2006 to require EVM to be used for all major system acquisitions in federal agencies.1 If EVM is not included in your contracting language, you need to speak with your chief acquisition officer and resolve this problem.

If the program managers and the contractors do not understand EVM, it is not surprising that the work breakdown structure is ineffective. After EVM has been properly instituted into the agency, all the project plans will need to be reviewed. Consider conducting an IBR. If there are so many problems with EVM and contracting, there are bound to be many more hidden issues among the individual investments.

Challenge Question 6:

Our IT contracts are based on time and material. At the agency I came from, we did not use EVM on these types of contracts, but in the agency where I currently work, the CIO wants to use EVM on all contracts, including time and material contracts. Do you agree with this approach and if so, how do we implement EVM on these contracts?

Response:

Task orders issued as part of a time-and-material contract must describe desired outcomes, and an agency must work with contractors to develop accurate EVM work breakdown structures and estimates to accomplish these desired outcomes.

Although the government is required to compensate the contractor for time and materials used to accomplish the task order, progress in doing so can be monitored and actions taken, if warranted, to make sure that the task order is successfully executed. Contractors recognize that if variance occurs consistently, the government can ask for the contractor to be removed or replaced or, in a worst-case scenario, work with the contracting officer to terminate the contract due to nonperformance.

In short, EVM can be used even on time-and-material contracts. As in all cases where EVM is used, however, work has to be structured and planned, accurate estimates must be developed, and work progress and variance must be monitored.

Challenge Question 7:

Should we use EVM for investments that are in operations and maintenance status?

Response:

This is a commonly asked question. Because EVM compares planned to actual cost and schedule to identify variance, it is best suited to monitor progress of initiatives that have a beginning, middle, and end. Projects, by nature, have these characteristics and are best suited for use of EVM.

When systems are placed in production, they tend to consume the same amount of resources each year, and they tend to function as expected throughout the fiscal year. Therefore the likelihood of cost or schedule variance is virtually nonexistent.

One exception is when, within the operations and maintenance budget, one or more projects are planned. In this case the project team can benefit by requiring that EVM be used for only those projects and not for the entire investment. This enables the project manager to monitor progress, manage risk, and take action if and when variances occur.

Challenge Question 8:

My agency just received responses from a request for information (RFI) solicitation that we issued two months ago in conjunction with a large multiyear IT development initiative. Three approaches were recommended, and the costs of each vary by as much as 200 percent. How do we analyze the results for a proper cost-benefit analysis?

Response:

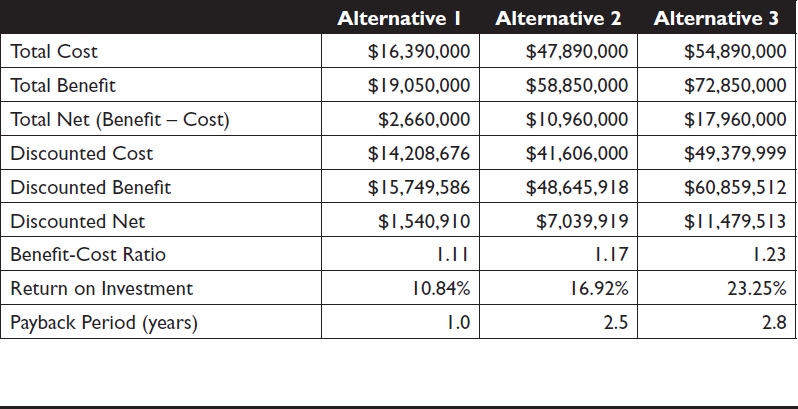

A cost-benefit model is needed for the three alternatives. Since costs were obtained as part of the RFI, they can easily be included in the model. The challenge is to identify benefits, and especially differences in benefits, among the three alternatives. If the benefits are the same for all three alternatives, the decision will be based on cost. Table 14-1 illustrates how the data for each alternative might be displayed for comparison purposes.

To account for the wide variation in cost, a sensitivity analysis should be conducted so that cost and benefit assumptions can be assessed, and any significant variances in estimate will affect the decision. (Sensitivity analysis is described in Chapter 9.)

Table 14-1 ![]() Example of a Cost-Benefit Analysis Comparison Table

Example of a Cost-Benefit Analysis Comparison Table

Challenge Question 9:

Forecasting the IT budget for the entire life cycle is a waste of time. We are already asked to forecast an 18-month budget, which is difficult because requirements are usually not known that far in advance. How can I estimate budget requirements for three, four, or five years from now?

Response:

Future-year budget projections are forecasts made under conditions of uncertainty. Everyone recognizes that such forward-looking forecasts are likely to be revised. However, to get a sense of scale regarding the size of the entire agency IT budget in future years, it is necessary to make a best-guess estimate. This does not mean that you should simply make it up; it means that logic should be applied to the estimate. For example, if the investment has been in production for only the past year, it is likely that the investment will be in operations and maintenance status for the next several years. So the budget should be similar to that of the past year but adjusted for inflation or other known events that might cause the investment to incur particular costs. In short, it is an estimate made using informed judgment.

Challenge Question 10:

We have a chronically under-performing IT system. It is cumbersome to use and because of design problems is difficult to maintain. Could an operational analysis be helpful in pinpointing the problems or should we take another approach?

Response:

The problems that you describe are clearly within the purview of an operational analysis. Often when we suggest that an operational analysis be done, investment owners grimace, especially in cases where they have just paid for an extensive security certification and accreditation review. An operational analysis takes only a fraction of the time, and most of the cost can be absorbed as part of the routine operations and maintenance budget.

The scope of an operational analysis encompasses performance evaluation, and the IT system was described as one that is chronically under-performing. As explained in Chapter 7, it is up to the operational analysis review team to set the scope, and certainly the technology platform can be included. Often, older technology is more costly to use and maintain, and it therefore has a direct impact on investment efficiency. The results of the operational analysis will likely lead to a recommendation for the investment to shift from operations and maintenance status to enhancement status in order to address the issues.

Challenge Question 11:

CPIC is really great, and I am very supportive of developing accurate budget and timetable estimates, but that is not how it works at our agency. Our users tell us what requirements we need to implement, when they need to have them completed, and what budget they have available to spend. Then we are expected to do whatever it takes to get the job done. They do not ask for cost or schedule estimates and, frankly, we cannot complain if there is not enough time or dollars available.

Response:

This situation should be reported to the agency CPIC-SG team leader so it can be raised at the next ITIRB meeting. It is the ITIRB’s responsibility to identify agency practices that limit CPIC effectiveness and to work with the agency’s executive committee to address them. In this case, IT funding has not yet been centralized and placed under control of the ITIRB. Therefore IT continues to be perceived as a “free good” that can be used (and maybe abused) in the normal course of business. Clearly, CPIC depends on rational decision-making, accurate estimation of costs and milestones, and management of IT projects as part of the whole investment portfolio. Your agency has work to do to comply with the Clinger-Cohen Act and to maximize its return on investment.

Challenge Question 12:

Our agency is composed of three very powerful, independent programs. The agency has a CIO, but each program also has its own CIO and CFO. Program directors are very powerful and protective of their systems and responsibilities and have not responded well to our suggestion to conduct an agency-wide portfolio analysis. Any suggestions?

Response:

You must convince your agency head and senior leadership that portfolio analysis is not an attempt to assume control over investment decisions but is in fact an opportunity to critically look at investments across multiple programs in ways that would not otherwise be done. The objective is to gain wisdom regarding investments owned by the agency and used by everyone so that opportunities to coordinate and collaborate can be identified.

Be certain to invite the CFO and budget officer to any portfolio analysis sessions. They tend to have detailed knowledge of the various programs and often are able to identify overlapping or redundant investments. Their participation will help support the perspective that the portfolio analysis effort is a worthwhile endeavor.

Conclusion

Adoption of information system technology has occurred over the past 50 years. At many times it has seemed like the “wild, wild West” in terms of trying to instill discipline and rigor in the decision-making process. And the results have often been painful.

Testifying before the U.S. Senate’s Committee on Governmental Affairs in 1998, Alan Greenspan, Chairman of the Federal Reserve System, stated:

The United States is currently confronting what can best be described as another industrial revolution. The rapid acceleration of computer and telecommunications technology is a major reason for the appreciable increase in our productivity in this expansion, and is likely to continue to be a significant force in expanding standards of living into the twenty-first century.2

Despite this promise, examples of major failures are well documented:3

![]() In 1999 the Bureau of Land Management pulled the plug on its much-anticipated electronic system for instant online access to millions of land and mineral lease records.

In 1999 the Bureau of Land Management pulled the plug on its much-anticipated electronic system for instant online access to millions of land and mineral lease records.

![]() The FAA initiated an ambitious modernization of its air traffic control system in the early 1980s. The project has experienced cost overruns, schedule delays, and performance problems. The initial estimate for modernization was $12 billion but the estimate was later revised to $45 billion. The FAA eventually cancelled the project.

The FAA initiated an ambitious modernization of its air traffic control system in the early 1980s. The project has experienced cost overruns, schedule delays, and performance problems. The initial estimate for modernization was $12 billion but the estimate was later revised to $45 billion. The FAA eventually cancelled the project.

![]() In 1992 the Health Care Financing Administration (now the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) initiated the Medicare Transaction System, which was intended to replace Medicare’s multiple contractor-operated claims-processing systems with a single system. The new system was to be fully implemented before the end of 1998. According to the GAO, the system originally was supposed to cost $151 million. By 1997 the estimated cost of the project had increased to about $1 billion. Faced with serious technical and managerial problems and runaway costs, the agency terminated the contract in 1997.

In 1992 the Health Care Financing Administration (now the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) initiated the Medicare Transaction System, which was intended to replace Medicare’s multiple contractor-operated claims-processing systems with a single system. The new system was to be fully implemented before the end of 1998. According to the GAO, the system originally was supposed to cost $151 million. By 1997 the estimated cost of the project had increased to about $1 billion. Faced with serious technical and managerial problems and runaway costs, the agency terminated the contract in 1997.

![]() The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) initiated the New Management System to perform eight accounting and management functions. After considering opportunities to use a COTS (commercial off-the-shelf) accounting system, USAID decided in 1994 to develop its own system. Because USAID did not follow accepted software development practices, the system had design deficiencies and software defects and could not operate effectively across the agency’s network.

The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) initiated the New Management System to perform eight accounting and management functions. After considering opportunities to use a COTS (commercial off-the-shelf) accounting system, USAID decided in 1994 to develop its own system. Because USAID did not follow accepted software development practices, the system had design deficiencies and software defects and could not operate effectively across the agency’s network.

Despite these problems, in 1996 the agency deployed the system worldwide as the primary system for conducting its business. After one year, USAID suspended operations at overseas missions and limited processing of financial transactions to its Washington, D.C., office. By FY1998, even though USAID had invested about $100 million to develop the New Management System, officials decided to replace it with an off-the-shelf system known as Phoenix.

These examples are included here for their sheer shock value, not to embarrass any particular agency or to dredge up past problems. Subsequent progress and successes have followed in many agencies—as would be expected following congressional attention and the associated publicity.

Despite problems such as these, the federal government has made substantial progress in terms of adopting and using information technology over the past 50 years. Agencies would be unable to carry out their missions without the IT systems and resources. Yet much more is possible. Citizens expect that government will be more accessible and more responsive to their needs and that technological innovation will make that possible. This should be the aspiration and goal of every government manager and employee—to identify new, exciting ways to carry out the business of government using new and emerging technologies.

The means for achieving this goal is through implementation of an effective CPIC process. Visionary leaders and motivated civil servants will recognize that this is true, and through their actions, words, and deeds, they will embrace the tools and methods that ensure that federal agencies and programs continually expect and pursue maximum return on IT investment.

ENDNOTES

1. Senator Fred Thompson, Government at the Brink, vol. 1, Urgent Federal Government Management Problems Facing the Bush Administration (Washington, D.C.: United States Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs, June 2001). Online at http://www.bbbonline.org/UnderstandingPrivacy/library/whitepapers/vol1.pdf (accessed December 2007).

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.