CHAPTER 6

IT Portfolio Analysis: Evaluation Techniques and Methods

Every day you may make progress. Every step may be fruitful. Yet there will stretch out before you an ever-lengthening, ever-ascending, ever-improving path. You know you will never get to the end of the journey. But this, so far from discouraging, only adds to the joy and glory of the climb.

—SIR WINSTON CHURCHILL, BRITISH PRIME MINISTER

The principles of portfolio management date back to money-lenders who conducted business thousands of years ago. Financial portfolio management is a methodology for structuring the best possible mix of investments in an asset portfolio and managing its performance to achieve specific investment goals. IT portfolio analysis shares many of the same characteristics as financial portfolio analysis. It involves the same level of vigilance and active involvement to ensure that the portfolio achieves the investor’s goals. It entails the use of a methodology to assess portfolio performance and a process for changing the asset mix as warranted to achieve the goal of maximizing return on IT investment.

Financial portfolio strategies vary depending on the investment goals. Younger investors who expect to work for many years are more likely to have wealth creation and growth as their goals, and their portfolio mix and investment strategy will likely be very different from those of older investors who have retired and are living off their investments. Older investors living off their investments are more likely to have an investment mix and strategy that are risk-averse and oriented more toward income than growth.

Successful investors spend considerable time analyzing both their portfolios as a whole and the individual investments they include. Investors adjust the mix based on changing portfolio characteristics. For example, when specific investments are not performing as well as initially expected, investors might consider selling. Portfolios are also mixed according to external factors like changes in financial circumstances or market conditions. The important point is that portfolio management requires active monitoring and involvement. Performance and external conditions must be monitored, and changes must be made when warranted to guide portfolio performance in a way that achieves investor goals.

If an agency owns more than one IT system, it has an investment portfolio. The agency builds its portfolio by approving and funding new systems and reinvesting in upgrades and enhancements to existing systems. The objective is to increase the value of an agency’s IT systems by investing in assets that have the highest potential to make the agency and its programs more effective and efficient. According to modern portfolio theory, an agency can reduce its investment risk by owning a diversified portfolio that includes systems serving different functions, in different life cycle stages, and with varying risk levels, so at least some of them can produce strong returns at any point in time.

Historically, agencies have not managed IT assets as a portfolio. Instead, various systems and infrastructure parts have been managed independent of each other. This is not to say that some agencies have not engaged in efforts to integrate assets, share information among them, and ensure compatibility, especially between applications and infrastructure. Rather, in most cases, such integration efforts have taken place after asset development, instead of as a planned part of the system design. For example, an agency might have commissioned the development of a new system to support its business processes without realizing that some of the same information is contained in other agency systems. The redundancy, when discovered, then necessitates an enhancement to ensure that the information contained in the two databases remains synchronized.

As a result of the relatively unplanned growth and expansion of IT assets over the past 50 years, numerous inefficiencies and problems may exist within an agency IT portfolio:

![]() Redundant data may be stored in more than one system, creating the potential for the data to become unsynchronized and necessitating complex processes and systems to keep them synchronized.

Redundant data may be stored in more than one system, creating the potential for the data to become unsynchronized and necessitating complex processes and systems to keep them synchronized.

![]() Systems that should be exchanging information may not do so.

Systems that should be exchanging information may not do so.

![]() Some systems were developed with technology that is incompatible with other systems, was acquired from vendors that have gone out of business, or has become obsolete.

Some systems were developed with technology that is incompatible with other systems, was acquired from vendors that have gone out of business, or has become obsolete.

![]() The number and cost of administrative systems may dominate the portfolio, crowding out investment in systems to support program functions.

The number and cost of administrative systems may dominate the portfolio, crowding out investment in systems to support program functions.

![]() Assets that were developed years ago may no longer effectively align with agency goals and objectives.

Assets that were developed years ago may no longer effectively align with agency goals and objectives.

![]() There may be an imbalance across the agency in terms of functions that are and are not supported by automated systems.

There may be an imbalance across the agency in terms of functions that are and are not supported by automated systems.

![]() The portfolio may be over- or under-weighted in terms of risk-return characteristics, meaning that there may be too many high-risk or too few high-return investments in the portfolio.

The portfolio may be over- or under-weighted in terms of risk-return characteristics, meaning that there may be too many high-risk or too few high-return investments in the portfolio.

![]() The portfolio’s investment age may be too high, indicating that IT investment is stagnant and that the agency is dependent on older systems that provide diminishing returns.

The portfolio’s investment age may be too high, indicating that IT investment is stagnant and that the agency is dependent on older systems that provide diminishing returns.

Adopting IT portfolio analysis as a methodology is an explicit decision to avoid the problems described above, and it is a proactive approach to maximizing IT return on investment.

IT Portfolio Analysis Principles

The Clinger-Cohen Act requires federal agencies to develop, maintain, and facilitate the implementation of a sound and integrated IT investment portfolio. The portfolio must align with the agency’s future vision and with efforts to expand use of e-government resources. For this reason and for other associated IT governance benefits, agencies should incorporate a portfolio analysis methodology into their CPIC and enterprise architecture (EA) governance processes.

The first step in implementing portfolio analysis is to assign responsibility for overseeing the process. Portfolio management is a key activity within the CPIC process and therefore should be managed by the ITIRB. The portfolio mix is changed by the CPIC planning and selection processes, and therefore portfolio analysis constitutes part of the CPIC planning process. Determinations made as part of the portfolio analysis can then be used as input for changes to existing investments or proposals for new ones.

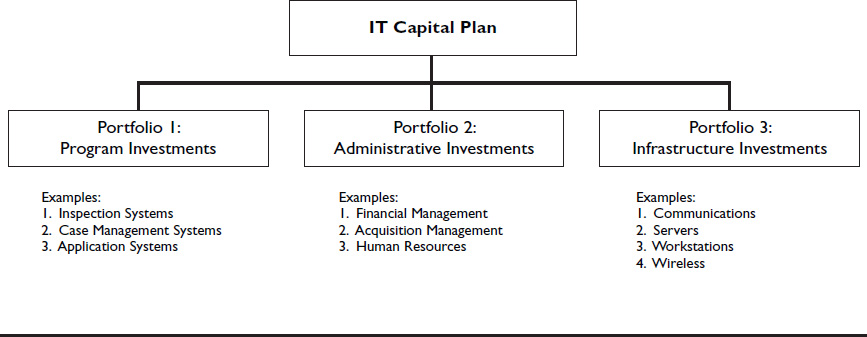

The second significant step in portfolio analysis is determining whether the agency should have one or multiple IT asset portfolios. The argument for having multiple portfolios is that it enables IT assets to compete for funding only with others in that portfolio, rather than have to compete with all of the agency’s assets. For example, if program systems and administrative systems are included in the same portfolio, it is possible that the ITIRB might have a bias toward funding one type of system over the other, leading to biased funding decisions.

The separation of infrastructure assets into a separate portfolio has an additional compelling rationale. The expected useful life of an application system is based on how well it supports user needs and meets their outcome-based performance objectives. Infrastructure, however, resembles building and facility investments because it requires ongoing expenditures for preventive maintenance to avoid rapid deterioration and decay.

The best example of a different investment strategy for infrastructure is the decisions that many agencies have made over the past decade to replenish agency workstations and servers on a three-year or four-year cycle, to avoid the technological obsolescence that plagued agencies during the 1980s and 1990s. Other parts of infrastructure, such as communications systems, database management systems, and server hardware and software systems, are equally vulnerable to technological obsolescence and therefore require programs of ongoing preventive maintenance rather than the development of business cases and similar methodologies used as part of the CPIC process. (This topic is discussed in more detail in Chapter 13.)

Establishing separate portfolios, as illustrated in Figure 6-1, with preset funding levels ensures that decisions are made within the same systems category rather than across systems with different purposes. The funding percentages for each portfolio could initially be based on historic spending levels. For example, an agency that historically spent 40 percent of its IT funds on administrative systems would, in the near term, allocate 40 percent to the administrative system portfolio. Funding ratios should be reviewed annually to accommodate changing priorities as needed.

Figure 6-1 ![]() Structure of Multiple Portfolios

Structure of Multiple Portfolios

It might take substantial time and effort to conduct the initial analysis of a portfolio. But after that analysis, and perhaps a second follow-up review, portfolio analysis should take considerably less time and effort because it will be managed within the CPIC and EA frameworks, decreasing the likelihood of new problems.

The remainder of this chapter discusses the process and methods that can be used for portfolio analysis. The objective is to regularly analyze the portfolio and monitor its performance, ensure that the right personnel are involved in the analysis, and link portfolio analysis and the CPIC process so that portfolio gaps and other issues can be identified. Problems are then referred to the ITIRB, which takes appropriate actions to ensure that the portfolio has the right asset mix to achieve agency IT goals and objectives.

Portfolio Analysis Process and Methodology

OMB does not prescribe a portfolio analysis methodology. Each agency must therefore develop and tailor an approach that best suits its needs and organizational culture. All agencies should take these basic steps, however:

![]() Establish and adjust funding ratios.

Establish and adjust funding ratios.

![]() Review existing portfolio assets using a variety of analytical techniques to identify performance gaps.

Review existing portfolio assets using a variety of analytical techniques to identify performance gaps.

![]() Compare results to enterprise architecture findings.

Compare results to enterprise architecture findings.

![]() Make recommendations to improve the portfolio, including suggestions for selecting and funding existing and new IT assets.

Make recommendations to improve the portfolio, including suggestions for selecting and funding existing and new IT assets.

Portfolio analysis is best conducted within a formal framework where the ITIRB delegates the portfolio analysis authority to groups or teams that then define roles and responsibilities, develop and implement policies, and establish decision-making practices. The objective of this formal process is to ensure that the IT portfolio is aligned with the agency’s strategy and direction, and that any needed adjustments are identified and presented to the ITIRB.

Portfolio analysis involves convening a group of knowledgeable individuals, collecting and organizing portfolio information, and using that information to draw conclusions about the IT portfolio. Involving individuals from various disciplines often helps broaden the analytical perspective. For example, including representatives from program functions that own the largest systems, so that they can represent their own interests, is important because they may have relatively more at stake. Including representatives from the CFO’s office and the budget office is also useful because they understand portfolio analysis principles and are knowledgeable about the financial aspects of agency IT spending.

Portfolio analysis should occur in two steps during a fiscal year. The first step involves analyzing the entire portfolio and should occur early in the fiscal year (between October 1 and December 31). This analysis provides an overall assessment of the IT portfolio and identifies strengths and opportunities for improvement. Senior leadership can then use this information to initiate action plans or set priorities to address identified portfolio gaps. This step also offers an opportunity to integrate portfolio analysis with the enterprise architecture and CPIC processes.

The results of the portfolio analysis should be used a second time during the annual budget cycle, as part of the CPIC selection process. ITIRB members can use portfolio analysis results in the same manner that they use enterprise architecture information: as additional input for making decisions and setting funding levels for existing and new IT investments. This occurs after taking action to create initiatives that will deal with portfolio analysis gaps and request the preparation of business cases for ITIRB consideration.

Methods for Analyzing the IT Portfolio

To analyze the IT portfolio effectively, a comprehensive inventory of all IT assets must be prepared. For most federal agencies, this likely has been done and is represented as the agency’s IT capital plan in the OMB Exhibit 53 form.1 If some IT assets are not reported in the IT capital plan, they should nonetheless be included in the portfolio analysis; if assets are grouped together in the IT capital plan, they should be identified individually.

Portfolio analysis requires sufficient preparation time so that information can be obtained, assembled, scored, and analyzed. Specific steps include the following:

1. Adopt a portfolio analysis methodology for assessing IT in-vestments.

• Determine if the agency will have one or multiple portfolios.

• Identify the investments to be included in each portfolio, including new proposed investments, investments currently being developed, and in-use investments.

2. Align the portfolio analysis initiative with the IT CPIC planning and selection phases.

3. Engage investment sponsors and owners, the chief information officer, the chief financial officer, and other key personnel in discussions about past, present, and future uses of IT assets.

4. Analyze the IT portfolio and identify opportunities to improve how it aligns with and supports the agency mission and goals.

• Develop evaluation criteria for analyzing the portfolio.

• Score each project according to the criteria.

• Assess the overall IT portfolio condition.

5. Make recommendations based on the portfolio analysis and present them to the ITIRB for consideration and action.

• Identify specific opportunities to strengthen the IT portfolio and increase return on investment.

6. Develop as-is and to-be models illustrating how resources are currently aligned and how the portfolio will change.

At the conclusion of these steps, sufficient information will be available to prepare a report and make a presentation to the ITIRB. During the analysis, it is possible that contentious issues will arise. For example, potentially long-simmering envy and frustration among organizational units may emerge, with some perceiving that others have had an unfair advantage and have received more IT funding. As a consequence, bias and other forces may derail efforts to objectively assess the portfolio and develop recommendations that are in the best interests of the agency as a whole. Care must be exercised to use appropriate facilitation techniques, and ground rules must be set to enable constructive discussions about difficult issues and allow bargaining and compromise to occur.

The quality and rigor of the analysis will determine if the portfolio analysis is a success. That rigor depends in large part on how much effort and how many resources the agency is willing to apply to the portfolio analysis initiative. It also depends on the structuring of analytical perspectives that best fit the investment portfolio.

The next section lists questions and issues that can be probed during the analysis, but it is likely that participants, who already know what IT investment “skeletons” are in the agency’s closet, can customize the approaches and issues presented herein as needed. Opportunity should be provided to discuss what criteria should be used, how to collect investment information to apply the criteria, the practicality of examining various performance dimensions, and other such issues.

Portfolio Analysis Criteria

The criteria offered here as standards for analyzing IT portfolios include cross-portfolio redundancy, system-to-system information exchange, technological compatibility, alignment with agency mission and goals, functional balance, risk distribution, technological maturity, and alignment with e-government initiatives. Many other criteria could be explored and included, but these serve as a good starting point and will provide sufficient rigor for the initial portfolio analysis.

Cross-Portfolio Redundancy

The problem of IT redundancy has manifested itself over the years. Notable instances have occurred where data reported by one agency to Congress were inconsistent with comparable data reported by a different agency in other reports or forums. When this occurs, the credibility of an agency and its senior officials suffers. Another example of redundancy is having several different offices within a single agency store a vendor’s contact information in their own systems. If the vendor changes that contact information but not all the offices make the correction, problems will ensue as orders, invoices, payments, and other information do not reach the vendor.

The review team should search across the agency’s entire portfolio for data content that exists in more than one place. As elements are identified, further analysis should determine if capabilities for manual or automated synchronization are in place. A scoring system should be used to define how serious the redundancy is: lower scores should be awarded for data elements that exist in multiple locations (the more locations, the more serious the problem) and for those that cannot be automatically synchronized.

System-to-System Information Exchange

After September 11, 2001, the problem of sharing intelligence information across federal agencies was highlighted as a key shortcoming.2 A Social Security Administration executive once remarked that one of the biggest challenges across federal agencies and between federal, state, and local government was something very simple: maintaining correct contact information, such as addresses and phone numbers. He was astounded that in the 21st century there was still no simple way to share a change of address among agencies. Without a central database, citizens must inform a wide range of agencies if their personal information changes.

Performing this kind of analysis can be challenging because it crosses boundaries both between and within agencies. Despite the difficulty, it is possible during the analytical process to anticipate the information-sharing needs and requirements of other federal, state, and local agencies. Identified information-sharing gaps should result in lower portfolio assessment scores for this criterion.

Technological Compatibility

For many years, federal agencies had diverse options when selecting underlying technology and commercial off-the-shelf packages. Systems could be built using a variety of database management systems, programming languages, reporting tools, and other technological products and features. Over time, some products lost favor in the marketplace, and vendors ceased to support and advance their capabilities. Federal agencies, however, elected to continue supporting the system because it was operational and met their basic requirements, even though its underlying technology was no longer supported by the vendor.

One consequence was that systems developed on one platform could not easily share information across platforms. For example, this was true when some agencies used a Unix-based operating platform while others used a Microsoft-based operating platform. This is just one of many examples.

Examining the IT portfolio for installed systems that are incompatible with other systems may result in the identification of investments that either cannot share data or that have expensive maintenance costs. In some cases, the technology might merely be incompatible with other systems; in other cases, it might have been acquired from vendors that have gone out of business. Identifying incompatibilities provides an opportunity to make recommendations to address them.

Alignment with Agency Mission and Goals

Agencies often are forced to adjust the focus of their missions and programs. After September 11, 2001, agencies responsible for safety regulation—such as the Federal Aviation Administration, Federal Railroad Administration, and Nuclear Regulatory Commission—were required to broaden their focus to incorporate security considerations. Other agencies sometimes change their goals and strategies in response to policy changes that come from the executive or legislative branches of government.

For this reason, it is useful to evaluate how well each portfolio investment aligns with and supports the agency’s mission, goals, and objectives. Preparatory work may be necessary to extract goals, objectives, outcomes, and other information from agency plans and budget documents. Once such information is gathered and organized, each investment can be scored in terms of how well it aligns with agency annual and strategic goals.

Functional Balance

Early IT economics dictated that agencies use automation for their administrative operations because (1) automation was best suited for processing large numbers of repetitive transactions, and (2) administrative operations tended to have the largest concentration of repetitive events such as accounting, procurement, and personnel transactions. For this reason, most agencies invested heavily in administrative areas.

The transaction benefit was expanded to other areas in the 1980s by the advent of office automation and departmental/local computing, and again in the 1990s by the Internet. Program functions that were not transaction-intensive could still achieve significant return on investment by implementing new systems. Some program areas that were less comfortable with technological advances may have made less progress over the years than others that were more tech-savvy.

Given such patterns of IT adoption, very useful information can be obtained for decision makers by an analysis of which functional areas in the IT portfolio have the largest number of investments, largest dollar amount of IT investments, most investment in new technology, and which receive the highest amount of benefit from IT investments. As the analysis progresses, it can help identify substantial gaps in agency areas that should be comprehensively supported by IT investments but are not. Analysis results can also prove useful in setting priorities and making decisions about future investment decisions.

Risk Distribution

Portfolios are likely to have varying risk profiles. If an agency has not developed or acquired a new system in many years and most or all of its systems are in use rather than under development, it is likely to have very little IT spending risk. Other agencies may have large systems under development and therefore represent a high risk profile. The difference between these two extremes determines how much attention and oversight must be devoted to high-risk portfolios to ensure long-term portfolio performance.

Developing the risk profile is useful because it can be used by the ITIRB in its investment decision-making. If ITIRB members already have a high-risk portfolio, considering additional high-risk investments might best be deferred until current risk levels are reduced.

As the review team analyzes the portfolio, it can use the business case, past ITIRB meeting reports, GAO reports, and other factors to identify levels of risk. In some cases, the agency and OMB might already have a high-risk investment list. Risk ratings can then be assigned to gauge overall portfolio risk.

Technological Maturity

It is common for some systems developed during the 1980s and 1990s to still be an important part of the IT portfolio, even though they were developed for the mainframe computing environment that used programming languages such as COBOL and older database management systems. This is especially true for some of the largest processing agencies in the federal government.

Evaluating technological maturity enables agencies to determine the relative age of individual investments and the portfolio as a whole. If a large percentage of the portfolio operates on contemporary technological platforms, agencies generally realize improved price-performance benefits. At the same time, modernizing or converting legacy applications that are highly complex and costly may not be practical. Knowing how much of the portfolio uses legacy technology and how much uses contemporary products and protocols provides an opportunity to render an overall assessment regarding the portfolio’s condition. It also enables recommendations for improving technology maturity, if warranted.

Alignment with E-Government Initiatives

As mentioned in Chapter 5, OMB has initiated a series of lines of business (LOBs) in areas such as grants, financial, human resource, and budget management. As part of its portfolio analysis, an agency should examine and score investments according to their similarity to designated e-government initiatives. The results should provide an opportunity to recommend the future direction for those investments that are similar in functionality to LOBs and should reveal which other investments are more agency-specific and not aligned with the LOBs.

Other Considerations

The preceding criteria are suited for analyzing the IT portfolio, but they may not be useful in examining other agency infrastructure. Other analytical approaches can be used as part of portfolio analysis. For example, total cost of ownership (TCO) is a commonly accepted analytical method for characterizing bundled categories of hardware, software, and maintenance costs. Also, enterprise tools and capabilities like data warehouses and web-based resources must be analyzed from a global perspective. Some of the preceding criteria may apply to such analyses, while others may not.

Communicating Portfolio Analysis Results

Communicating the results of the portfolio analysis is as important as the analysis itself. Recipients of the report will expect to learn about the macro-conditions of the IT portfolio. For example, how many investments are in use and how many have substantive development taking place? How much does the agency invest in IT on an annual basis? How much has it invested over the past several years? If data for the past ten years is available, it should be communicated because it conveys spending patterns and trends.

Other characteristics and generalizations arising from the portfolio analysis can be included in the introduction of the report, such as the number of systems or the amount of money supporting various functional areas, for example.

Recent trends and major initiatives can also be highlighted. It is useful to mention any progress made in recent years from the use of an enterprise architecture, which is also designed to improve portfolio performance.

A description of the criteria used to score the portfolio and the actual scores should also be made available to the ITIRB. Explanations for observed issues, such as the clustering of investments in specific functional areas, the distribution of investments along the risk continuum, or other significant findings, should also be included.

The evaluation criteria should also be discussed, including difficulties in obtaining the data to use for scoring and any difficulties encountered in applying the criteria. For example, it is usually more difficult to score investment alignment if agency goals and objectives are vaguely worded.

An overall statement of the portfolio’s condition should also be included in the analysis report. Participants should reach consensus regarding the overall condition and should select highlights of both good and bad portfolio characteristics that support their overall conclusions.

Portfolio Analysis Tools

Because of the recent emphasis placed on portfolio analysis, many vendors have developed systems that support portfolio development and capture critical portfolio characteristics and information, including Primavera® ProSight, for example. Some include evaluation and scoring methodologies, and most include impressive visual capabilities, enabling users to examine the portfolio from multiple viewpoints and to obtain information about the portfolio that might not otherwise be available.

Selection of a portfolio analysis tool should be coordinated with the CPIC and EA teams because existing tools may already be available and in use. Careful research should be conducted before making a selection, for the products are often expensive and, in some cases, complex and difficult to use.

ENDNOTES

1. Office of Management and Budget, Circular A-11: Preparation, Submission, and Execution of the Budget, Part 2, Section 53, “Information Technology and E-Government,” July 2007. Online at http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/circulars/a11/current_year/s53.pdf (accessed December 2007).

2. Government Accountability Office, “Information Sharing: The Federal Government Needs to Establish Policies and Processes for Sharing Terrorism-Related Information,” March 2006. Online at http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d06385.pdf (accessed December 2007).