CASE STUDY 3

Real Options

K. Leslie and M. Michaels

BEST PRACTICE IN MANAGING REAL OPTIONS

Two UK companies, BP and PowerGen, exemplify the benefits of real-options thinking. Between 1990 and 1996, BP increased its market value from $18 billion to $30 billion, representing a total return to shareholders of 167%. Over the same period, PowerGen raised its market value from $1.4 billion to $3.8 billion, a return of almost 300%.

In both cases, most assets and earnings were in mature industries. BP's exploitation of North Sea oil and gas field development options took place against a background of falling reservoir sizes and volatile oil and gas prices – quite unlike the boom days of the 1970s and early 1980s. PowerGen, for its part, has had to deal with barely rising demand, a saturated market and increasing competition to build new capacity.

Both companies managed to earn extraordinary returns in unfavourable environments because they followed a strategy of making incremental investments to secure the upside while insuring against the downside. They also delayed committing to investment until they had confirmed that it would be worth while, usually by acting on the six levers of option value.

Extending the Field of Vision

The application of real options steers management towards maximizing opportunity while minimizing obligation, encouraging it to think of every situation as an initial investment against future possibility. As a result, management's field of vision is extended beyond long-term plans too rarely properly reexamined, to encompass the full range of opportunities available to it at any moment. Real-options thinking achieves this through its most basic contribution and its most striking departure from the dicta of net present value: the attitude it fosters to uncertainty.

For BP, the economics of a prospective oil or gas field are highly uncertain in terms of margins (oil prices fluctuate, operating costs are unpredictable) and volume (recoverable reserves are difficult to estimate at the start of the licensing, exploration, appraisal and development process). The company has responded by embracing uncertainty. It has increased its exposure to volatile undeveloped prospects by accumulating licences that exploit the flexibility to respond to new technology and operating practices in order to make currently uneconomic prospects profitable. It is a strategy that has transformed BP's view of the North Sea's potential.

For PowerGen, the electricity pool is uncertain in terms of price and volume. The company's strategy evolved from “secure baseload with minimal uncertainty” to “explore opportunistic operating strategies.” The outcome was a shift from a net present value approach that would have maximized the baseload volume of a few plants and closed all the others, to a policy of increasing operational flexibilities to respond to the market – and capturing marginal volumes at high prices.

In an increasingly uncertain world, real options have broad application as a management tool. They will change the way you value opportunities. They will change the way you create value – both reactively and proactively. And they will change the way you think.

HOW BP MAXIMIZES THE VALUE OF ITS OILFIELDS

As noted earlier, the sequence of spending decisions that leads to the development of an oil or gas field constitutes a classic real option. First, a company acquires a licence to explore; then it engages in low-cost seismic exploration. If the results are promising, exploratory drilling is undertaken.

If the exploratory well is positive, appraisal drilling takes place. Full development – and most expenditure – goes ahead only if these preliminary stages are completed satisfactorily.

While correct, this description captures no more than the value of the real option's reactive flexibility. Had BP acted on reactive flexibilities alone, it would probably not be earning superior returns in mature provinces like the North Sea, where profitable low-risk investment opportunities were exhausted long ago. By the same token, new opportunities such as those west of Shetland and in certain high-pressure/high-temperature areas of the UK continental shelf require heavy capital investment and carry geological and technical risks, so they usually appear uneconomic under net present value analysis. But because cumulative holding costs are so low and the payoff can be huge if the geological, technical and partnership uncertainties are resolved, almost any option value justifies holding on to such leases.

BP paid the penalty for taking a limited, reactive flexibility approach when it developed the giant Magnus field in the early 1980s. It took an overcautious view of the forecast production plan and built too small a platform. Had proactive flexibilities been considered, higher production might have been achieved. As it was, production was constrained, and Magnus was obliged to pump for an expensive extended period, rather than following the optimal path of build-up, brief peak and long decline.

When the company has taken proactive flexibilities into account, however, the results have been remarkable.1 Its handling of the Andrew Field is an example. The field was discovered in the mid-1970s but not developed at the time because it was small and, given the drilling technology of those days, required huge investment. The oil price collapse of the mid-1980s and subsequent market volatility made the prospect of development even dimmer. Yet by the mid-1990s, through the application of so-called breakthrough thinking, experimentation, the creation of learning networks and benchmarking, BP had developed radical approaches to drilling, field development, project management, and the sharing of benefits with the contracting industry. What the company did, in effect, was to buy an out-of-the-money option to develop the Andrew Field, defer exercising the option until it had proactively driven down the exercise price (that is, the investment in development), and then exercise an option that it had turned into an in-the-money one.

Exploiting proactive flexibility in the case of oilfield development licences involves all the steps to reduce capital costs that BP took in the case of the Andrew Field, along with measures to minimize the cost of the real option. The licence bid and its holding cost are the option price – as critical a part of the management equation as the six levers of option value (the same is true in financial options). The holding cost can be reduced by renegotiating spending obligations such as a commitment to a government to drill exploration wells, or a commitment to a partner.

As always, it is worth comparing real-options thinking, reactive and proactive, with net present value along the six levers of the options model. The most sensitive levers are increasing the present value of expected cash inflows and reducing the present value of expected fixed costs.

The means to pull both these levers is the application of new technology to obtain more reliable profiles of an oilfield's value, better total oil recovery, and more efficient production facilities (fewer wells, lighter platforms). The next most sensitive lever, increased uncertainty and hence price volatility, makes an option more attractive, but management cannot influence oil prices. At the less sensitive end of the spectrum, the option's duration should be managed to trade off potential improvements in cash inflow and outflow against the cost of holding the option and the risk of losing “dividends”.

NPV analysis could allow for some of this potential through different scenarios. The danger, however, is that a classic net present value “go/no go”, all-or-nothing decision would underestimate the value of expected cash inflows, which could result in a production facility incapable of handling higher-than-expected volume, as in the case of the Magnus Field. Net present value analysis would seriously undervalue volatility, accentuating the risk-averse behaviour already skewing forecasts and budgeting. Go/no go thinking also implicitly assumes (usually incorrectly) that the investment opportunity will be unaffected by competitor behaviour.

It should be clear by now that the lessons of real-options thinking apply as much to existing assets as they do to new areas of exploration and development, where they are much more often applied. Declining or exhausted oilfields are a case in point. Net present value analysis would probably suggest they be closed down. But keeping them running not only effectively defers new investment and saves the cost of removing redundant facilities (sometimes much higher than anticipated, as the enormously expensive Brent Spar incident two years ago showed)2, it also keeps open the option of benefiting from the development of new technologies.

For instance, satellite unmanned gas platforms in the southern North Sea, extended-reach drilling (enabling wells to be bored into a reservoir tens of kilometres from a platform originally installed to service a nearby reservoir), and sub-sea templates that pump oil back to far-off platforms all make it possible to use processing capacity that would otherwise have become surplus as soon as the original reservoirs were exhausted. Such developments have greatly increased the option value of fields originally exploited with no thought of such possibilities.

In these circumstances, the importance of options thinking lies less in the way the present values of cash inflows and outflows are managed, and more in the recognition of the value of the option's duration. By exercising options to extend the life of existing infrastructure (thus driving down development costs), and by managing competitors' and its own incremental investments – variables that net present value ignores or oversimplifies – BP has managed to commercialize many small oilfields as its original giant fields have declined.

POWER MASTER-STROKE BY POWERGEN

In 1990, the UK government privatized the electricity generating industry. At a stroke, the stable market enjoyed by a state-owned monopoly was replaced by an unpredictable environment of fluctuating prices. A pool (or spot market) was established into which generators had to sell their electricity, and which priced electricity by the half-hour on the basis of bids from power stations. The new market is characterized by hour-to-hour and seasonal volatility – a nightmare for generators in a highly capital-intensive industry.

At the time, most generating stations were coal-fired baseload stations designed to generate more or less continuously. The variable nature of electricity demand and the availability of environmentally and economically attractive supplies of natural gas fuelled the “dash for gas”: the development of combined-cycle gas turbine (CCGT) stations that could be switched on or off according to requirements, reaching full capacity without technical problems in 15 minutes. Most coal stations – PowerGen's among them – were forced out of baseload into periodic production, to which they were unsuited. Many were forced to close.

Net present value analysis of the dilemma faced by coal-fired stations would have suggested driving down costs (an insufficient measure, given the superior economics of CCGT); or hedging electricity output (which would have protected against the downside risk of losing market share but only at the price of eliminating the upside potential); or closing the plant to avoid investing against an uncertain cash inflow. Real-options thinking however, enabled PowerGen to exploit three variables ignored in net present value thinking – uncertainty, duration and dividend – to create a profitable business.

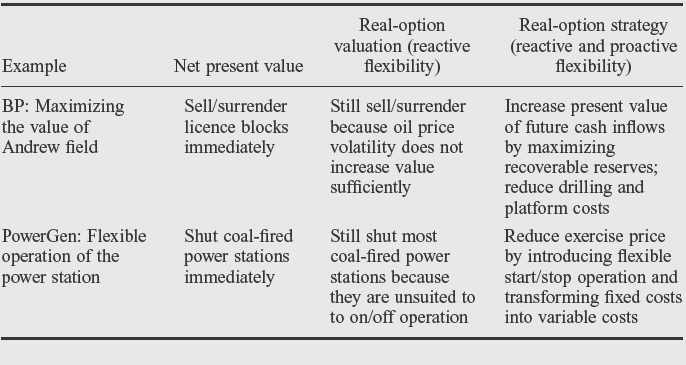

Price volatility meant that, for short periods, coal stations could earn large margins and would thus be worth life-extending investment, provided that PowerGen's operating staff rapidly developed the technological and operational flexibility to acquire two key capabilities (see Table C3.1):

Table C3.1 Real-option valuation and strategy versus the net present value approach

- The ability to switch coal plant on and off frequently. New operating skills such as managing the chemical balance in the boilers, in combination with limited investment such as the use of hardened chrome headers to prevent boilers cracking as tubes heat and cool, now enable some PowerGen stations to start up more than 200 times a year. Typical US coal-fired stations start up just eight to 10 times a year.

- The ability to bid economically for marginal business by converting fixed costs into variable costs through the aggressive use of contractors.

Rather like BP, PowerGen raised its aspirations by benchmarking, by stretching its management to surpass world best practice, and by freeing business units and teams to find the best route forward. PowerGen ultimately enjoyed a double benefit, in fact, because unpredictable shutdowns of nuclear plants, combined with volatilities in supply and demand, have caused periodic shifts to coal production and an increase in prices.

NOTES

1. See “Unleashing the power of learning: An interview with British Petroleum's John Browne”, Harvard Business Review, Sep–Oct 1997, for BP's own account of its value-creating strategy since 1992.

2. Shell sought to sink the redundant storage platform Brent Spar in mid-Atlantic, arousing a storm of protest.

“The Real Power of Real Options”, by K. Leslie and M. Michaels, reproduced with permission from The McKinsey Quarterly No 3. Copyright 1997 McKinsey & Co.