10

Operating Exposure

D. R. Lessard and J. B. Lightstone

Treasurers are familiar with the impact of changes in exchange rates on the dollar value of assets and liabilities denominated in foreign currencies. The impact of changes in exchange rates on operating profit expressed in home currency, which we will call operating exposure, is often more important to the company but much less understood. Interest in the effects of exchange rates on operating profit has been increased by the growing awareness of global competition, as well as by the ongoing debate over the accounting treatment of exchange gains and losses.

Operating exposure is often the major cause of variability in operating profit from year to year and an understanding of operating exposure is a necessary input into many decisions of the company. In the long term, operating exposure should be considered in setting strategy and world-wide product planning. In the short term, an understanding of operating exposure will often improve operating decisions. At a business unit level, the quality of a business and the effectiveness of its managers should be evaluated after taking into account exchange rate effects on reported performance which are outside management control.

The increased importance of operating exposure has developed in several ways. Exchange rates are volatile in the current world of managed floating rates. Also, markets are becoming increasingly global. For example, the US no longer has a dominant world market share in key industries but shares markets more equally with Europe and Japan. As a result of these changes, we expect exchange rate effects to impact the operating profits of companies in globally competitive industries, whether or not they export their products. In fact, the effect of changes in exchange rates on operating profit is often important for companies with no foreign operations or exports but which face significant foreign competition in their domestic market.

This article outlines the concept of operating exposure and the appropriate business and financial responses to manage this exposure and has three parts:

- Exchange rate environment.

- Understanding operating exposure.

- Measuring operating exposure.

EXCHANGE RATE ENVIRONMENT

To understand the impact of exchange rates on operating profit, we need to understand both the long- and short-term behaviour of exchange rates.

The exchange rate environment is characterised by a long-term tendency for changes in the nominal US dollar/foreign currency exchange rate to be approximately equal to the difference between the rates of inflation in the price of traded goods in the US and the foreign country.1 If the inflation rate in the US is 4 per cent greater than the Japanese inflation rate during the year, the Yen will tend to strengthen approximately 4 per cent against the dollar. This long-term relationship between exchange rates and price levels – usually called purchasing power parity (PPP) – implies that changes in competitiveness between countries, which would otherwise arise because of unequal rates of inflation, tend to be offset by corresponding changes in the exchange rate between the two countries. However, in the short-term of six months to several years, exchange rates are extremely volatile and have a major impact on the relative competitiveness of companies selling into the same market but sourcing from different countries.

This change in relative competitiveness in the short term is the result of changes in the nominal exchange rate which are not offset by the difference in inflation rates in the two countries. If the Yen strengthens 4 per cent against the US dollar and the Japanese inflation rate is 1 per cent, a US exporter into a Japanese market served primarily by Japanese producers would see his dollar price increase by 5 per cent. However, if the inflation rate in the US is 4 per cent, which is 3 per cent higher than the inflation rate in Japan, the operating margin of the US producer will only increase by one percentage point. This example (and other examples developed later in more detail) show that the change in relative competitiveness does not depend on changes in the nominal exchange rate – the number of Yen we obtain for each US dollar – but on changes in the real exchange rate, which are changes in the nominal exchange rate from which are subtracted the difference in inflation rates in the two countries.2 In the case of our US exporter into Japan, the change in the nominal exchange rate is 4 per cent but the change in the real exchange rate (which flows through to operating profit) is only 1 per cent.

Changes in real exchange rates reflect deviations from purchasing power parity, so that the cumulative change in the real exchange rate tends to be smaller than that of the nominal exchange rate over a long period of time. In the short term of six months to several years, both nominal and real exchange rates are volatile, with implications for the profitability of the company. This volatility of real exchange rates in the time-frame of six months to several years gives rise to an exaggerated variability in operating margin.

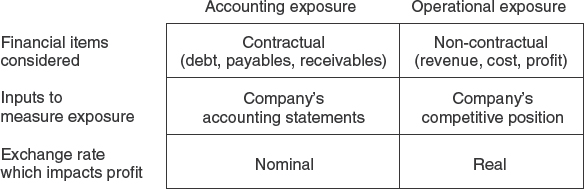

UNDERSTANDING OPERATING EXPOSURE

The traditional analysis of currency exposure (Figure 10.1) emphasises contractual items on the company's balance sheet, such as debt, payables and receivables, which are denominated in a foreign currency and whose US dollar value is affected by changes in the nominal exchange rate. The company may enter into forward contracts to cover this contractual exposure. A traditional analysis recognises two types of impacts on the profits of the company, which arise from translation of outstanding contractual items as of year-end and transactions involving contractual items closed out during the year. The information required to define this contractual or accounting exposure is obtained from the accounting statements of the company. Under the US accounts standard FASB 52, physical assets also enter into the calculation of translation gains and losses. However, in general these translation gains or losses will bear little or no relationship to the operating exposure of the company.

In economic terms, these contractual items are properly identified as exposed to changes in exchange rates. Our problem lies in the fact that, in many cases, this contractual exposure captures only a small part of the total impact of exchange rates on the company, which should properly include the effect of changes in real exchange rates on non-contractual items, such as revenues, costs and operating profit. If a company covers its contractual exposure, it may be increasing its total exposure because of the operating exposure component of total exposure which has not been separately identified. The operating exposure and contractual exposure of the company may have different origins, so that in many cases the two exposures will indeed have opposite significance.

Both contractual exposure and operating exposure must be taken into account by the company, so that the two approaches are complementary and not mutually exclusive. Unfortunately, the difference in emphasis in considering each type of exposure tends to introduce a sense of defensiveness in practitioners who have historically only managed contractual exposure. A balanced perspective is not helped by the fact that the effects of changes in nominal exchange rates are separately identified in the income statement but the effects of changes in real exchange rates on revenues and costs are not similarly recognised.

The effects of changes in exchange rates on operating profits can be separated into margin effects and volume effects. We shall illustrate each kind of effect by a series of examples based on composites of companies studied.

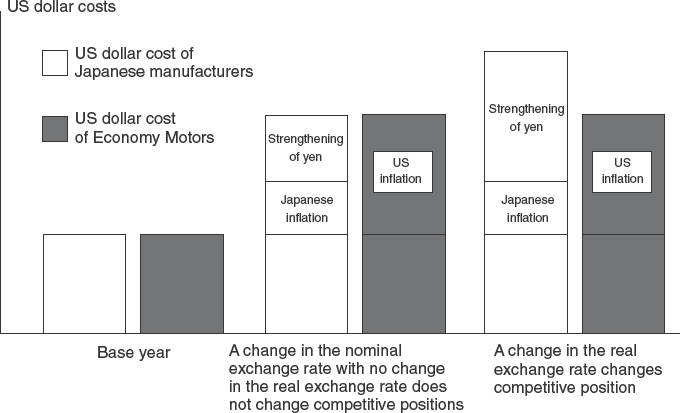

Economy Motors is a US manufacturer of small cars, that purchases inputs in the US and sells exclusively in the domestic market and has no foreign debt. From a traditional point of view, Economy Motors has no exposure to changes in exchange rates: in fact, however, the operating profit of Economy Motors is exposed to changes in the real yen/US dollar exchange rate.

Economy Motors competes in the US small car market with Japanese manufacturers which are the market leaders. The Japanese companies take into account their yen costs in setting a dollar price in the US. The competitive position of Economy Motors is shown in Figure 10.2. In some base year when the yen and the dollar are at parity, the dollar costs of Economy Motors are assumed to be equal to the dollar equivalent costs of its Japanese competitors and Economy Motors enjoys a normal operating profit margin.3 In some later year, if the yen strengthens in line with PPP, to offset a higher inflation rate in the US than in Japan, there is no change in the competitive position of Economy Motors. The increase in the dollar equivalent costs of the Japanese companies from Japanese inflation plus the effect of the yen appreciation is equal to the increase in the costs of Economy Motors from US inflation. In this case, the nominal exchange rate has changed with no change in the real exchange rate and there is no change in the competitive position of Economy Motors. However, if the yen strengthens relative to the dollar by a greater amount than required by PPP, the dollar equivalent costs of the Japanese companies will be greater than the costs of Economy Motors and there will be a strengthening in the competitive position of Economy Motors relative to its Japanese Competition.

This example illustrates several characteristics of operating exposure:

- Operating exposure bears no necessary relationship to accounting or contractual exposure.

- Operating exposure is determined by the structure of the markets in which the company and its competitors source inputs and sell products. The measurement of operating exposure must accordingly take into account the nature of the company and its competition. The measurement of accounting exposure has traditionally looked to the company alone.

- Operating exposure is not necessarily associated with the country in which goods are sold or inputs sourced. Economy Motors, for example, is a US manufacturer selling in the US market and has a significant yen exposure.

- Operating exposure is not necessarily associated with the currency in which prices are quoted.

- Operating profit varies with changes in the real exchange rate. The nominal exchange rate may change without any change in the real exchange rates and with no effect on operating profit. Conversely, the nominal exchange rate may remain constant while the real exchange rate is changing and impacting operating profit.

The importance of the details of market structure in determining operating exposure is easily seen in Examples 2 and 3.

Specialty Chemicals (Canada) Limited is the Canadian subsidiary of a US company which distributes chemicals produced in the US by its parent. As a distribution subsidiary with few fixed assets, it has little debt. It quotes prices in Canadian dollars. When the Canadian dollar weakens relative to the US dollar, there is a decline in the US dollar value of its Canadian dollar receivables and, from an accounting viewpoint, Specialty Chemicals is exposed because of these receivables.

When we look beyond the accounting treatment, we recognise that when the Canadian dollar weakens, the cost of Specialty Chemicals will increase in Canadian dollars. This raises a number of questions:

- Does Specialty Chemicals have a Canadian dollar operating exposure?

- Should Specialty Chemicals construct a Canadian manufacturing plant to match revenues and costs?

- Should the company issue Canadian dollar debt, so that if the Canadian dollar weakens, there will be a reduced US dollar value of its repayments?

We cannot answer these questions by looking at Specialty Chemicals alone; we have to examine the structure of the marketplace in which it sells its products. We find that Specialty Chemicals and all its competitors import products from the US, with no significant production in Canada. Any increase in Canadian dollar costs will be felt equally by all companies, without any change in their relative competitive position, and will be reflected very quickly in an increased price. The responsiveness in price offsets the cost responsiveness so that there is no operating exposure except in the very short term. Issuing Canadian dollar debt or building a plant in Canada will introduce a new operating exposure where there was no operating exposure previously.

Operating exposure often differs substantially among companies which at first glance appear similar but where the companies sell into markets which have a different structure. For example, Home Products (Canada) Limited, like the previous case, is also a Canadian subsidiary of a US company which purchases product from its US parent. However, the competitors of Home Products (Canada) Limited have manufacturing facilities in Canada and have the major share of the Canadian market. If the Canadian dollar weakens in real terms, the Canadian dollar costs of Home Products will increase without any associated increase in price. There is a cost responsiveness without any offsetting price responsiveness, so that Home Products has a Canadian dollar/US dollar operating exposure.

Changes in the real Canadian dollar/US dollar exchange rate will affect a Canadian exporter into the US with a small share of the American market in opposite ways to Home Products. When the Canadian dollar weakens in real terms, there will be a decline in the profits of Home Products but an increase in the profits of the Canadian exporter.

Home Products can reduce this exposure by building a plant in Canada or entering into a financial hedge which offsets the effect of the change in the real exchange rate. Alternatively, if Home Products increases its share of the Canadian market to become the market leader, it may be able to raise prices to offset some or all of the increased Canadian dollar costs caused by a weakening Canadian dollar and thereby reduce its operating exposure.

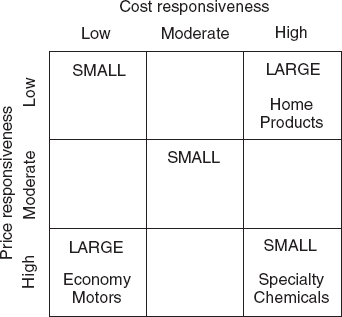

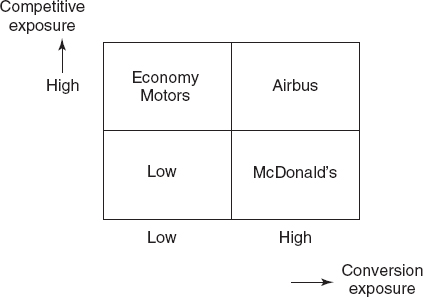

Figure 10.3 illustrates the effect of various combinations of cost responsiveness and price responsiveness on the magnitude of the resulting operating exposure.

Figure 10.3 Operating exposure matrix

The same analysis can be applied to the more realistic but also more complex case of companies that compete globally rather than in specific national markets. Consider the case of International Instrumentation, a US company that sells precision measurement instruments throughout the world and is the market leader in its industry. Its prices are approximately uniform across countries, as product requirements do not vary from country to country and transhipment costs are small relative to the value of the product.

Demand is insensitive to price, as its products represent a small fraction of the total costs of its customers. Nevertheless, prices and margins are not allowed to be so high that other firms possessing the relevant technologies would be encouraged to enter the market. International Instrumentation will set its prices with a view toward its costs and the costs of actual and potential competitors. If most of its potential competitors are also based in the US, its prices in dollars will be relatively independent of exchange rates. If International Instrumentation is attempting to discourage potential competitors which are located in other countries, it will set lower dollar prices in periods of relative dollar strength.

Contrast the above example with Earthworm Tractors, a US-based manufacturer of heavy construction equipment. Its prices vary somewhat across countries because of variations in product specifications and substantial shipping costs, but it nevertheless faces substantial global competition. However, in contrast to International Instrumentation, it faces two major competitors: Germany and Japan. The cost positions of the three firms are such that exchange rate changes shift cost and price leadership and, as a result, basic world prices, whether measured in US dollars, yen, or euros, respond to exchange rate changes.

These examples illustrate some further characteristics of operating exposure:

- Operating exposure is introduced by differences between competitors in sourcing or technology or country of manufacture.

- Companies which are market leaders will tend to have a reduced operating exposure.

- Operating exposure is specific to a particular business. A company is likely to have a variety of operating exposures among its subsidiaries doing business in any given country and the operating exposures of these business units must be evaluated separately. This is in contrast to a standard accounting treatment which aggregates the exposure of the various businesses in a company.

- It will generally be possible to identify two companies which have opposite operating exposures with respect to the same real exchange rate.

So far we have focused on the impact of changes in the real exchange rate on operating margin. In some cases, changes in real exchange rates will have their most important impact on volume.

United Kingdom Airways is a UK-based charter airline which sells airline transportation and package tours to the US. When sterling weakens relative to the US dollar in real terms, there were fewer UK travellers to the US. As travel cost is only about 30 per cent of the total cost of a vacation, there is little that a seller of travel services can do to offset the increasing cost of a trip to the US.

Laker Airways had a similar operating exposure. Laker was a UK-based company whose marketing seems to have been primarily directed to UK travellers. With a marketing strategy which was more evenly balanced between travel originating in the US and the UK, changes in the real exchange rate would have had relatively little effect on the demand for total air travel between the two countries. Fewer British tourists would visit the US when the US is relatively expensive from a British perspective but this would be offset by more US travellers to Britain. Laker transported an increasing number of British tourists until 1980. This was to a large extent the result of a sterling strengthening beyond its parity with the dollar, with the implication that eventually sterling would again weaken to regain parity. However, in 1980, Laker financed new aircraft purchases in US dollars, in effect doubling its exposure to the subsequent weakness in the pound.

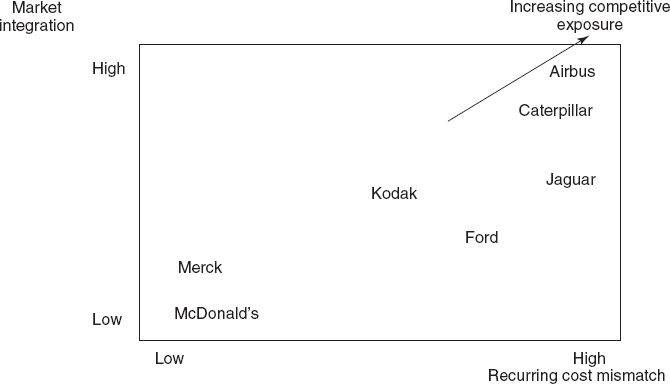

In summary, several factors contribute to the nature and severity of the company's competitive exposure. There include the degree of cross-border market integration, the extent of global competition, the extent to which the cost structure of the industry is variable versus fixed, and the extent to which the industry is characterised by lead competitors with differing costs. Figure 10.4 illustrates the competitive exposure of various companies combining the degree of currency mismatch in costs and the relative importance of variable versus fixed costs.

Turning to actual examples, Airbus is a company with an extreme competitive exposure. It sells its product in international markets in direct competition with Boeing, although almost all its costs are in European currencies. The market is almost completely integrated and the variable cost component of aircraft manufacturing is substantial. Caterpillar is another company that has a similar high degree of competitive exposure, because the market for its products is highly integrated and it faces in most of those markets a key competitor, Komatsu, which has a very different cost structure.

At the other extreme lie some pharmaceutical companies such as Merck. Here, market integration across national boundaries is low as national regulation serves as an effective barrier to transhipment. Also, the variable cost component of producing products is low, and substantial advertising and distribution costs are incurred in the country of sale. Another company with relatively low competitive exposure is McDonald's, which receives franchise fees as a percentage of sales from its operations in various countries. These fees are effectively denominated in local currency as relatively few people cross the Atlantic to arbitrage the “Big Mac” and there is little cross-border integration of markets and most variable costs are incurred in the country of sale.

Figure 10.4 Determinants of competitive exposure

Figure 10.5 Components of operational exposure

Jaguar4 is an example of a company with a moderately high competitive exposure, as it has a variable cost mismatch as great as that of Airbus or Caterpillar, but a somewhat lesser degree of market integration between Europe and the US because of the greater differentiation of its product and its ability to control distribution channels. Nevertheless, even though Jaguar is a unique product, its pricing in the US cannot differ substantially from the pricing of other luxury cars. Companies like Kodak and DEC also fit into this middle category.

Companies such as Merck and McDonald's, which have low levels of competitive exposure, nevertheless have substantial operating exposure to exchange rate changes because of the conversion effect. Their US dollar profitability from foreign operations will change in time with real exchange rates. Figure 10.5 shows companies with various combinations of competitive and conversion exposures.

MEASURING OPERATING EXPOSURE

Contractual or accounting exposure is readily identified with any desired degree of precision from accounting statements. However, operating exposure cannot be directly estimated from accounting records, and will not have the precision of an estimate of contractual exposure. On the other hand, the operating exposure of a company may be far greater than its contractual exposure.

We have been able to estimate operating exposure in two ways, a bottom-up estimate, which relies on a detailed understanding of the competitive position of the various businesses of the company and a top-down estimate, which is derived from an analysis of the historical profitability of the company.

Bottom-up Estimates

A bottom-up measurement of operating exposure requires an understanding of:

- the structure of the markets in which the company and its competitors source inputs and sell their products; and

- the degree of flexibility of the company and its competitors in changing markets, product mix, sourcing and technology.

We have been successful in obtaining this information in a structured dialogue with operating management. Most managers have the information to answer these questions but lack the analytical framework to use this information, and usually the treasury group will have the responsibility of coordinating the process of measuring operating exposure. For many companies this represents a closer involvement of the treasury group with operations and an enlarged treasury responsibility. This involvement of the treasury function in operating considerations reflects the fact that the impact of exchange rates on the profitability of the company is in some sense a financial effect, to a large extent outside the business control of the company, and yet it corresponds to a very important aspect of the external competitive environment.

This exposure audit with operating management will typically include the following types of questions:

- Who are actual and potential major competitors in various markets?

- Who are low cost producers?

- Who are price leaders?

- What has happened in the past to profit margins when real exchange rates have become overvalued and undervalued?

- What is the flexibility of the company to shift production to countries with undervalued currencies?

These questions are usually well received by operating management, because an understanding of the operating exposure of a company can be used directly to improve operating decisions and it is critical to measure management performance after taking into account exchange rate effects. In Example 1, Economy Motors is likely to be more successful in increasing market share during a period of weakness in the dollar, when its Japanese competitors are seeing decreasing yen equivalent prices, if management has previously anticipated this set of circumstances in contingency planning. There is also less conflict in the management of operating exposure between the welfare of a partly owned foreign subsidiary and its parent whereas these conflicts are often present in the management of contractual exposure.

Top-down Estimates

The bottom-up process of dialogue with operating management is likely to be time-consuming and costly. We have also developed top-down analytical techniques to estimate operating exposure at the company level or at the level of individual business units. This analysis can be performed quickly. We have found that it is an effective method of communicating the operating exposure of the company to senior management, in particular when the exposure of the company arises from import competition in the domestic market.

The top-down estimate is derived from an analytical comparison of the historical profitability of the company with the changes in profitability expected on the basis of changes in real exchange rates assuming that the competitive position of the company is constant during the period of the comparison and that the company has not undergone major structural changes at the level of aggregation under review.

The effect of changes in real exchange rates on the profitability of the company will be determined by the volatility in exchange rates and the fraction of revenues exposed. The top-down analysis identifies both the principal exchange rates to which the company is exposed and the fraction of revenues exposed.

If the exporter has some market power in the overseas marketplace, the exposure will be limited to some fraction of his total revenue and there will be less volatility in mark-up and operating profit. Similarly, the exposure of Economy Motors (Example 1) is limited to some fraction of its revenues which corresponds to the power of Japanese importers in the US marketplace. However, in general, the volatility in earnings may be a cause of financial distress to the company. In an environment where there is not a good understanding of the exchange rate cause of this volatility, management decisions will often not take advantage of the underlying business opportunity.

The top-down estimates of operating exposure have identified many companies where a large part of the variability in the profits of the company results from exposure to real exchange rate effects, in some cases with only a small fraction of the revenues exposed. In the absence of an analytical framework to demonstrate these operating exposure effects, there is a tendency for them not to be fully recognised by management, whose culture in many cases will want to attribute the success of the company to the performance of its operating management.

NOTES

1. The exact relation is that ![]() 12 = (

12 = (![]() 1 −

1 − ![]() 2)/(1 +

2)/(1 + ![]() 2). where

2). where ![]() 12 is the fractional change in the spot exchange rate (currency 1/currency 2) and

12 is the fractional change in the spot exchange rate (currency 1/currency 2) and ![]() 1 and

1 and ![]() 2 are the annual inflation rates in country 1 and country 2.

2 are the annual inflation rates in country 1 and country 2.

2. More exactly, the fractional change in the real exchange rate is ![]() 12 − [(

12 − [(![]() 1 −

1 − ![]() 2)/ (1 +

2)/ (1 + ![]() 2)].

2)].

3. The argument can be extended to the case when the US dollar costs of Economy Motors in the base year bear their normal relationship (but are not necessarily equal) to the US dollar equivalent costs of its Japanese competitors.

4. Jaguar's parent company is Ford. The commentary on p. 242 and the depiction of the competitive exposure of Jaguar and Ford in Figure 10.4 relate to the circumstances of the companies prior to the acquisition of Jagnar by Ford in 1989.

“Operating Exposure”, by D. R. Lessard and J. B. Lightstone, reproduced with permission from Management of Currency Risk, edited by B. Antl. Copyright 1989 Euromoney Books, tel 020 7779888, e-mail books@euromoneyplc.