CASE STUDY 10

Who Rates the Raters?

STARTING in 1909, a dense book from John Moody would thud on to subscribers' desks in America, following days or even weeks in the post. The annual railroad-bond ratings were out. America's fledgling debt markets moved accordingly.

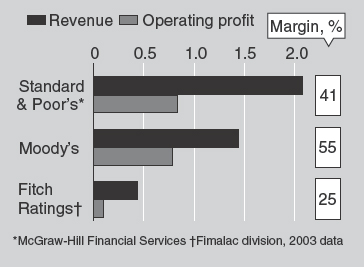

Moody's business still thrives almost a century later. Credit ratings – assessments of the likelihood that an issuer will default on the interest or principal due on its bonds – now shoot through the market at internet speed and cover bond issues of all kinds. Whether a company has the highest possible AAA rating or a BBB- plays an important part in determining the rate at which it can borrow. In America only a bold or foolish company, municipality, state or even school district would try to issue debt without first getting a rating from Moody's, Standard & Poor's (S&P), its chief rival, or Fitch, a French-owned upstart that has become the world's third-biggest rating agency (see Figure C10.1).

The leading ratings firms have lucrative franchises and face only limited competition in a business that, thanks to the growth of global capital markets, has greatly expanded. These days, S&P, for example, rates $30 trillion of debt, representing nearly 750,000 securities issued by more than 40,000 borrowers. All three big raters are highly profitable, with Moody's enjoying the highest operating margin – of more than 50% of revenues.

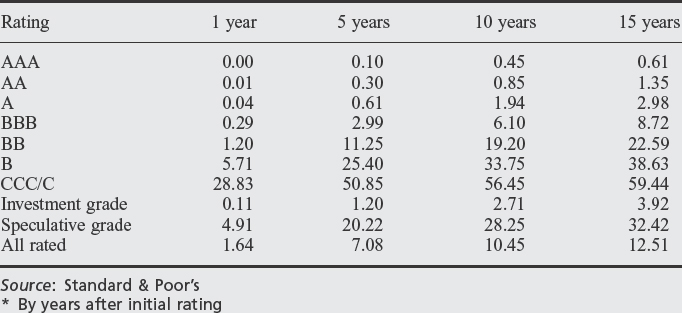

Credit ratings have been embraced by financial markets because they mostly do what agencies claim they do – accurately predict the likelihood of defaults. The agencies' overall long-term record is a good one (see Table C10.1).

But they have also faced heavy criticism in recent years, for missing the crises at firms such as Enron, WorldCom and Parmalat. These errors, the agencies' growing importance, the lack of competition among them and the absence of outside scrutiny are beginning to make some people nervous. This month regulators in America, the biggest market for ratings, called for more oversight of the agencies.

As debt markets have expanded, ratings have been built into financial arrangements of all kinds. Mutual funds and government-run pension funds often restrict their investments to certain grades of bonds, typically excluding those rated as “junk”. The Basel 2 accords on bank-capital requirements, concocted by the world's central bankers and due to take effect in 2007, require regulators to use ratings in assessing banks' sturdiness. More controversially, during the era of corporate scandals it emerged that many banks had build so-called “ratings triggers” into their loan agreements. There meant that, if something happened to lower the borrower's creditworthiness to a specified level, the loans could be called in. Several high-profile cases, notably Vivendi in France, were trapped in liquidity crises as a result.

Figure C10.1 Smooth operators: Credit-rating agencies, 2004, $bn

*McGraw-Hill Financial Services. †Fimalac division, 2003 data. Source: Company reports.

Table C10.1 Good grades Cumulative average corporate default rates* 1981–2004 %

The agencies' power raises questions about their role and methods that have not been fully answered. Critics argue that the business is riddled with conflicts of interest because the raters are paid for their work by the bond issuers, rather than by investors who actually use the ratings (a change from old railroad-bond days). In addition, the big agencies are trying to grow consulting businesses that advise on matters which could affect their ratings, done by the same big agencies. This seems, at least on the face of it, a potential source of conflicts of interest.

S&P launched its “Risk Solutions” business in 2000, aimed mainly at helping banks meet Basel 2 requirements. Vickie Tillman, head of ratings at S&P, insists that “there is no relationship between that business and the ratings business; no mixture of personnel.” Moody's “Rating Assessment Service” offering does mix personnel – the company views it as an extension of assigning ratings – but Raymond McDaniel, Moody's president, says he does not expect this business's contribution to rise above 1% of annual revenues. Consulting units (Fitch has one too) compete head-on with investment banks, almost all of which have highly profitable teams that advise corporate clients on how to manage their finances in order to impress the raters.

Others in the industry are dubious about this development. “Firewalls are really good until it gets really hot,” says Glenn Reynolds of CreditSights, an independent credit-research firm. “It is an absolute parallel to what the auditors went through” when they tried to expand from auditing to consulting.

Indeed, the conflicts inherent in the agencies' business model have raised fears that the rating industry might be asking for regulatory trouble. The agencies are, says Mr Reynolds, “the most powerful force in the capital markets that is devoid of any meaningful regulation.” Sure enough, this month in America, William Donaldson, chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) told a Senate committee that Congress should allow him to regulate the industry.

That prospect alarms the big agencies, which are stoutly defending their role and business practices and would prefer a voluntary code of conduct. They have begun by explaining more to outsiders, including journalists, how they work and what methods they use to set ratings. Critics have charged that many ratings are assigned almost arbitrarily. The agencies, of course, argue that they are impeccably thorough.

STEP BY STEP

When a company or government wants to issue debt, it usually calls a rating agency (or three, to boost credibility). Analysts then spend weeks, sometimes months, poring over data and interviewing company management. The team reports back to a committee of senior ratings staff. The committee formally decides the rating, although it usually follows the lead analyst's recommendation. If the issuer objects to the conclusion, some agencies allow it to veto the release of the initial rating. (When a new issuer has only one rating, the market may assume that a second rating is “hidden” in this way.)

Ratings are re-evaluated annually unless something happens that merits further attention. They change for many reasons – merger prospects, revenue shortfalls, regulatory changes and so on. Issuers retain the right of appeal if they feel wronged, although unlike an initial rating they cannot elect to “hide” subsequent ratings. The agencies say they will hear an appeal when the issuer provides new information or shows that their analysis is faulty, but they actively discourage sour grapes appeals.

But can an agency objectively assess a company that is paying its bills? Rating agencies argue that they manage this difficulty by barring analysts from involvement in fee negotiations. Further, say the raters, any individual issuer contributes only a tiny proportion of the rating agency's revenues, though some companies such as General Motors (GM) and General Electric would seem to carry more weight because they issue masses of debt. In this context, notes Ms Tillman, the fact that a recent study by a lobby group found one-third of issuers to be unhappy with their ratings is reassuring evidence that the potential conflict is, in fact, well managed.1

The “issuer pays” conflict is more worrying when it comes to the rating agencies' efforts to acquire new business. Sometimes agencies issue a rating even when the issuer has not requested it and has no intention of paying for it. The agency must then rely on public information to decide the rating. In other words, if the firm paid up, the rating might be more accurate.

Targeted companies despise such practices, which Mr Reynolds of CreditSights describes as “the equivalent of extortion”. Carne Curgenven of Brit Insurance, a specialist insurer, has gone through this experience with his company's syndicate at Lloyd's, London's insurance market. Moody's has been rating the financial strength of the syndicate for years (S&P started more recently) without payment or agreement from Brit. Moody's methodology in particular, he says, caused him concern. But when he contacted Moody's, the response was that nothing could be done while the syndicate was not interacting: in other words, payment would open doors. Moody's says its methodology is “robust”, and that “a more accurate analysis is not contingent on payment.”

Rating agencies defend unsolicited ratings in two ways. First, they say that such ratings are designed to broaden their own understanding of the market. “If we want to be competing with S&P and Moody's, it's really bad if an investor phones us up and says ‘I saw your opinion on Ford, it was interesting, what do you think about BMW?’ And we say, “Actually, we don't cover them’,” says Paul Taylor, managing director of Fitch.

Second, the agencies argue that unsolicited ratings are the only way for new ratings competitors to get a foothold. This seems somewhat disingenuous coming from the likes of S&P, which hastens to add that “way less than 1%” of its ratings are unsolicited. Moody's says it discontinued unsolicited ratings five years ago owing to widespread misunderstanding of the practice, though it continues to analyse a small number of companies (it will not say exactly how many) whose initial unsolicited ratings pre-date 2000.

Fitch probably does the most unsolicited rating – up to 5% of its portfolio. But it emphasises that it will accept information from a firm's managers even if it is not paying for a rating. Should the fact that a rating is unsolicited be disclosed to the market? Logic and practice say it should. S&P has only recently clarified its policy and now flags all unsolicited ratings: Fitch and Moody's also provide such flags.

Although critics generally accept the long-term validity of ratings, there has been vociferous criticism of the agencies' short-term performance. They conspicuously failed to predict the sudden collapses at Enron and WorldCom, which were rated investment-grade until the last minute. They were also slow to realise that senior managers at Vivendi were exploiting the agencies' traditional reluctance to force an issuer to make public highly sensitive internal financial information. In Vivendi's case, among other factors, hidden information about inter-company loans almost brought the company down.

WE'RE NOT WATCHDOGS

The agencies respond, reasonably, that they cannot be expected to spot frauds based on audited numbers or an intent to deceive them. But why, asks Frank Partnoy of the University of San Diego's law school, were the big agencies maintaining investment-grade ratings on Enron's debt when the bad news was mostly out and its share price had slumped to $3?

Similarly, how could S&P, Moody's and Fitch have been so oblivious to Asia's gathering financial problems in the mid-1990s (only to catch up with repeated downgrades once the problems were widely known)? And why do the agencies now keep ratings for GM and Ford just above investment grade, when the markets trade their bonds at spreads equivalent to junk status? The implication in all of these cases is that the agencies are reluctant to face the broader consequences of their decisions. By moving slowly, they avoid the accusation that their actions might lead to financial turmoil of one kind or another.

Rating agencies argue that speed is not their job – only accuracy. They are simply issuing a long-term opinion about creditworthiness and not trying to move the markets, or ride the ups and downs of the business cycle. “Investors don't want volatility from credit-rating agencies,” says Mr Taylor. The agencies point out that they signal their intentions to the market ahead of a downgrade, typically by putting an issuer on “watch” status. But investors say that market prices are a better short-term indicator of trouble.

Big investment managers, equipped with their own bond-research teams, can profit nicely if they think the market has mispriced bonds in response to ratings decisions. “When the raters do something strange and spreads move significantly, we hope to take advantage of that,” says one. Enron's collapse, for example, proved a fantastic buying opportunity because the agencies, fearful of more scandal, slashed corporate-bond ratings. “A lot of companies' bonds traded at 50 to 55 cents on the dollar, but they weren't going under,” says Mark Kiesel, a strategist at PIMCO, a fixed-income manager.

UNDER-RATED?

Perhaps the biggest shadow hanging over the ratings industry is its perceived lack of competition. The business functions as an oligopoly. Upstarts have a hard time breaking in because it takes years, even decades, to build a sufficient reputation. “It is difficult for a rating agency to pop up because you need a 20-year track record,” says one asset manager. Fitch is an unusual case because it was formed from several established agencies. Mr Reynolds thinks this could happen again with, say, Indian, Japanese and European agencies coming together. Private-equity funds, he says, could help pull something together. Others in the industry think more sector-specific rating agencies will emerge.

Ironically, the only power which America's SEC really has over rating agencies is to designate which ones are acceptable – and for three decades that has effectively impeded competition. Plenty of pension funds and other investors stipulate that their bond investments must have a rating from a “Nationally Recognised Statistical Rating Organisation”, the SEC'S designation. Some states have laws that specify S&P and Moody's. The fact that the SEC recently designated two more agencies as “nationally recognised” is misleading. S&P and Moody's still dominate the market, there and worldwide. The industry remains a duopoly or, at best, an oligopoly in important new areas such as structured finance (i.e., repackaged pools of assets).

One result is that there is little price competition between agencies. When asked how Moody's sets prices, Mr McDaniel explains that it decides annually after assessing how much value its services add. “We do not base our prices on someone saying ‘We're going to get a cheaper deal down the street’,” he says.

Fitch has been gaining ground as the third force in the business. In January it was admitted to the Lehman Brother's bond index, so its ratings now matter for all bonds included in that index. Following a similar move last year by Merrill Lynch, this was seen as an important stamp of approval. “Three is a big difference from just two,” says one asset manager.

Still, Fitch admits that it has not really prospered by stealing business from S&P and Moody's, but rather by expanding the use of ratings. “We've benefited greatly from companies going for more than two ratings,” particularly in America, says Mr Taylor. S&P and Moody's, he adds, are “so powerful that a company would be incredibly reluctant to drop their rating.”

In fact there are plenty of thriving local rating agencies, especially in continental Europe and Japan. European companies have traditionally held information close, and some have resented the idea of being assessed by a big American firm. But resistance has weakened. Mr McDaniel characterises Europe as a “very good growth opportunity” for Moody's, in particular for ratings for complex structured financings.

Large credit markets exist in China and India, where local rating agencies are springing up (S&P is in talks to increase its stake in one of India's biggest agencies). Other developing markets are also opening up, as firms there shift away from a traditional reliance on bank loans towards funding debt in the capital markets.

But for big international issuers of debt there is little choice, especially since they will often want a rating from at least two agencies. Regulators are waking up to the problem. This month the SEC recognised AM Best, which specialises in the insurance industry, as a nationally acceptable rating agency (Dominion Bond Rating Service, a Canadian firm, is the fifth officially sanctioned rater.) Still, for many bond investors the imprint of S&P or Moody's will drive decisions for a long time to come. The system works, but, as one asset manager says, “You probably wouldn't invent” it to serve today's financial markets.

A NATURAL OLIGOPOLY

Is there room for a fourth or fifth global agency? One might emerge, but there might also be a natural limit to how many can thrive. Issuers content to have three ratings on their debt, might not unreasonably balk at paying for a fourth. Indeed, real competition to the established rating agencies could come from other quarters. Plenty of small firms assess credit and, unlike the agencies, make buy and sell recommendations as well. These firms charge subscribers rather than issuers, so pension funds and other investment managers that lack the resources to monitor the bond market themselves could hire one of these outfits. “The market is requiring more intensive coverage,” says Kingman Penniman, who runs a research firm called KDP.

But the rise of independents, as well as the growing importance of other predictors of default such as credit-default swaps and other financial derivatives, are unlikely to slow down the expansion of the rating agencies' reach as financial markets continue to grow around the world. The agencies are now so woven into the fabric of the investment community that, barring a huge scandal, any changes are likely to be slow and incremental. Nevertheless, regulators have a reasonable case for gaining the power to monitor them a bit more closely. They should also encourage, as much as they can, more competition between the agencies – above all to avoid any transformational scandals like those which have already hit auditors and investment banks.

NOTE

1. The study can be found at: http://www.afponline.org/pub/pr/pr_20041018_cra.html

Reproduced from The Economist (26 March 2005), pp. 91–3.