CASE STUDY 14

An Interview with Microsoft's CFO

Bertil E. Chappuis and Timothy M. Koller

When Microsoft announced, in July 2004, that it would tap its legendary cash reserves to return some $60 billion to shareholders, analysts immediately began scrambling to understand what the move might say about the software giant's strategy, its growth prospects, and the maturation of the entire hightechnology sector.

For John Connors, Microsoft's chief financial officer, however, the decision to pay a onetime special dividend amounting to about $30 billion and to buy back as much as $30 billion of the company's own shares over the next four years was merely the latest in a series of financial moves that have positioned it at the cutting edge of financial innovation in the high-tech industry. In 2002 Connors helped reconfigure Microsoft's financial-reporting processes around seven clearly defined business units, each with its own CFO and profit-and-loss statement, to offer investors a greater degree of organizational stability and transparency. The following year, the company surprised many people by announcing that it would stop compensating employees with stock options and would instead issue stock awards.

Connors believes that this combination of initiatives has helped build a stronger value culture at Microsoft while permitting management to focus on performance in the company's increasingly diverse business lines. In an interview at Microsoft's headquarters, in Redmond, Washington, he talked with McKinsey's Bertil Chappuis and Tim Koller about the thinking behind Microsoft's finance moves, the company's plans for growth, and the role of finance in the next era at Microsoft.

The Quarterly: The first dividends for Microsoft come out in December. What was the strategic rationale for how much cash Microsoft holds onto, disburses in dividends, and applies to share buybacks?

John Connors: The first thing was to keep enough cash on hand to give us flexibility to manage things like a severe short-term economic dislocation or investment opportunities. We haven't publicly said how much cash that will be, but it's probably fair to assume that, after the upcoming distribution, we will still have around $25 billion to $40 billion on hand.

Even holding that much back, we still have a lot of money to distribute. We also had a number of constituencies pushing us to do different things with it: growth investors wanted a very large-scale buyback; income-oriented investors were clamoring for an increase in the regular dividend; and some investors just wanted all the money back so that they could decide what to do with it. Of course, we also had our employees, who now have stock awards as well as options from our legacy program.

We concluded we had enough cash to do something substantial on all fronts, but we decided against a huge buyback. Not only would that have disappointed the investors who simply wanted the cash but it would also have been a monumental undertaking. Our analysis also showed that if we had committed ourselves to a $60 billion share buyback, we could have ended up purchasing 5 to 8 percent of our stock every day that the Nasdaq allows us to buy our own shares for the next three years, and some of that inevitably would have been uneconomic. So we decided to take that $60 billion and use roughly half of it for a special onetime dividend, with the rest committed to a multiyear buyback. That's a pretty significant percentage of the enterprise value, and a fairly decent percentage of the shares.

We believe that this strategy will reward all of our investors. It will also increase growth in profits and cash flow, which are what drive our valuation and our return to shareholders.

The Quarterly: Any rules of thumb about how much cash companies need to remain flexible?

John Connors: We have a relatively unique model, in that our business is not capital-intensive. What drove our approach is that Bill [Gates] and Steve [Ballmer] and the board are pretty conservative. We don't want to be in the position where we have to make decisions because of the balance sheet. And while we don't anticipate that we would ever have a year with expenses but no revenue, we'll probably keep at least one year of operating expenses and cost of goods sold in cash on hand – that's around $20 billion in cash and short-term investments.

We also want to have enough for acquisitions. We have made a series of acquisitions, some of them for cash. And while most of them have been fairly small, we also want to be able to make some game-changing investments if we so choose. Any large acquisition would likely be a combination of cash and equity.

The Quarterly: The high-tech industry is seriously underleveraged. Are we seeing the beginning of a fundamental change in capital structure? Do you think the industry will take on more debt over the next couple of years in order to increase returns on equity?

John Connors: I don't think we have seen any large-scale move in that direction yet, primarily because tech companies still have high P/Es relative to most other industries. The growth rate assumption priced into tech companies' stock is that tech will continue to grow faster than other industries, although the differences in growth assumptions between tech and other industries have begun to narrow.

The real question would be whether the market starts assessing technology companies the way it measures companies in other industries. For startups, the last thing in the world a company like Google is worried about right now is whether or not it should have debt. While there will continue to be great start-up home runs, I don't see why the Wall Street analysis of midsize and large tech companies would be different from that of companies in other industries five or ten years from now. So if the market starts to measure technology in terms of returns on equity, capital, and assets, you will probably see more financial engineering of technology companies to bring them in line with companies in other industries.

The Quarterly: It has been a couple of years since Microsoft reorganized its financial reporting along business-unit lines. What has the impact been and has it lived up to expectations?

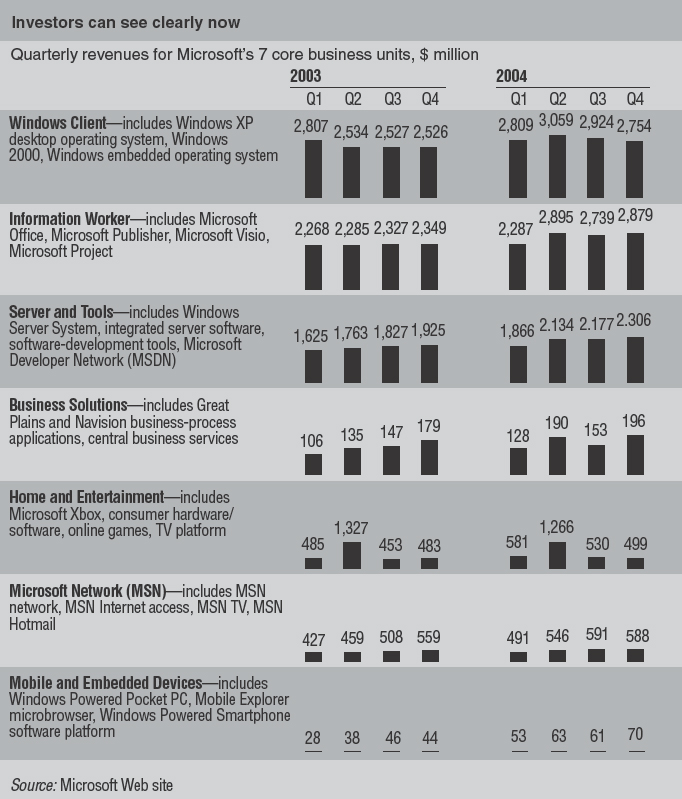

John Connors: One of the most positive outcomes is the transparency the reorganization created. Prior to 2000, Microsoft was viewed largely as a two-product company or a desktop company with phenomenal success in Windows and Office. But in the mid-1990s, we had expanded into gaming and mobile devices and into business applications for small to midsize companies. By 2001 people were not really certain which businesses we were involved in. Today the outside world can easily see Microsoft's business units and how well they are doing against their competitors. Now investors can answer the following questions every quarter: How is our Home and Entertainment Division competing against Sony? MSN against Yahoo! and Google? Our server and tools business against IBM and Oracle? How are we competing with Nokia in mobile devices? Investors can also easily track the performance of Windows and Office as well as the company's growth beyond those two products.

The P&L focus also forced some improvements in resource allocation. One of the big challenges we faced in 2001 was that, because of the company's orientation toward long-term investment, our research and development efforts had created a broad range of new products that often outpaced our capacity to sell and support them. Complicated products like the BizTalk server created a great opportunity to automate many business processes, but in order for our customers to earn the best returns on the purchase of our products they also needed specialist salespeople who understood the supply chain, data warehouses, and financial flows. In some rapidly growing categories, we also lacked a coherent worldwide brand proposition for certain unique products, compared with our brand proposition for the company as a whole. In the end, we had to decide what areas required continued investment – and what areas did not.

As the bubble collapsed and technology spending slowed, it became very clear that we could not continue to invest at the same levels. Today we all know how much money we have to invest, and we all have to agree on how much will go into R&D, sales, marketing, and tactical initiatives.

The restructuring also forced a degree of organizational stability and continuity. Historically, Microsoft had a major reorganization once a year that coincided with our budgeting in the spring. This process worked very well when we were smaller, had fewer units in fewer geographies, and weren't invested in so many segments. But as the company got larger and more complicated, we heard from customers and partners that Microsoft was hard to keep track of. So once we organized around these seven business groups and reported along those lines, customers and partners believed we were serious about them.

The Quarterly: Did anything about the move surprise you?

John Connors: It was surprising how many people within the company didn't really understand how intensely analysts, investors, and the press would follow each of these seven businesses. A lot of our businesses had flown under the radar, and while we would talk about their long-term opportunities in a way that investors appreciated, after a while they also wanted to see how those investments were performing. Now there's a quarterly scorecard that reports – both relatively and absolutely – how we are doing.

Second, it was surprising how difficult it was to synchronize what we called the “rhythm of the business” between our field organization and the business groups. Traditionally, our field, or geographic, organizations could move both people and marketing around to take advantage of opportunities and to adjust to changing market conditions. While the P&Ls of our field organizations still matter today, and they still have a revenue quota, the business groups now have the ultimate financial accountability and make the final resource allocation decisions. The field is secondary in authority. That was a big shift, and if you look at companies that have had collapses in financial performance, it often has to do with the shifting of financial reporting from product to geography or vice versa. So we took a relatively measured step over a two-year period.

The Quarterly: What about the impact of the restructuring on the finance function specifically?

John Connors: It has allowed us to push much harder on performance because the finance folks in those groups report solid line into the business, dotted line back to the finance function in the center of the company. And it's much easier now for the center of the company to push on financial performance.

It's also helpful that this model can easily accommodate growth. When we want to do a deal, it's very clear that the CFO and the business-unit leader are on point for that deal. If we want to add new businesses, we have a model that will scale.

Last, the restructuring has allowed us to talk about the role of finance in the next generation of Microsoft, which is quite different from its traditional role.

The Quarterly: How will finance at Microsoft differ in the next generation?

John Connors: When we restructured, we decided very early on to designate as CFO the lead finance person in each of our seven businesses. This model is fundamentally different from the one Microsoft had in the past.

Historically, the top position outside the center of the company was a controller, whose role was to control and measure. But today the finance function must do more. For example, if you look at the incredible diversity of the company now – the number of businesses, the different models, and the economics of some of the new businesses – Microsoft today requires much stronger strategy and business-development functions. Business units like MSN and Home and Entertainment are entering into multibillion-dollar contracts and alliances over long periods of time. Our mobile-devices business requires a very different alliance model with handset carriers and telecom operators than any we have had. Add the requirements of the Sarbanes-Oxley legislation and you find that the control and risk-modeling function has to be at a much higher level than it was three or four years ago.

In practical terms, that means we have a greater number of senior business leaders in finance than we had prior to 2002. Of 125 corporate vice presidents, for example, 9 are now from finance, whereas before there would have been 2 or 3. And corporate-finance leaders at that level also have different requirements: they have to be able to nurture other great business leaders, who then move into marketing, services, and sales, and they have to be articulate spokespeople for the company at technology conferences and industry events.

The Quarterly: What's the most value-added role a CFO can play in a high-tech company?

John Connors: We are in an era today when technology isn't really different from any other industry. In the 1990s it was just growing a heck of a lot faster than GDP. In the late 1990s the dot-com and telecom meltdown made it pretty clear that such growth had been part of a bubble. It's unrealistic to expect that an industry this large will grow substantially faster than GDP.

So a technology company's CFO must be good at both topand bottom-line growth. The skills that a CFO has at Wal-Mart or GE or Johnson & Johnson are much closer to what will be expected at technology companies now.

Technology also resembles other industries in that its consolidation focuses mostly on cost synergies rather than growth synergies. At least in the near term, Sarbanes-Oxley requires CFOs of companies in every industry to spend a significant amount of time on how a company's ethical or business-integrity tone emanates across the organization. How does its internal-control structure operate? How does its disclosure-control process operate? And is it being really, really clear with investors in its SEC filings and press releases? Sarbanes-Oxley tends to make CFOs focus on similar tasks regardless of the industry.

The Quarterly: Speaking of Sarbanes-Oxley, what are the costs versus the benefits when it comes to implementing Section 404, for example?1

John Connors: Publicly traded US companies have historically had a premium on the equity side and a discount on the debt side relative to other markets because of the value of transparency and trust that investors had in US markets. That trust and transparency got violated, and we all have to bear the cost of earning it back. Microsoft accepts that.

Of course, there are negatives in Sarbanes-Oxley. For example, there isn't much guidance on what is material for public-company financial statements – not in the legislation itself or in the regulations or rules yet – nor is there any case law defining this. There are far too many areas where companies could take a reasonable risk with good business judgment but still be subject to litigation.

Yet there are real benefits to Sarbanes-Oxley. In our case, we knew what our key controls were, we knew what our materiality threshold was, we had tight budgeting and close processes and strong internal and external audits, but we didn't document everything in the way that Sarbanes-Oxley legislation requires. So we have done a complete business-process map of every transaction flow that affects the financials. In so doing, we have improved our revenue and procurement processes, and we can use controls to run the company in a more disciplined way. So we have gotten real business value out of all that process documentation.

Sarbanes-Oxley also really forces you to evaluate the policies that are in place and whether they make sense. One of its requirements is that if a company has a written management policy, people are expected to follow it – whether or not it has a financial impact. For example, how much can people discount contracts?

Even if a company can record that contract exactly right from a GAAP2 perspective and the financials are correct, are people following the discount policy? At Microsoft, we have taken a really fresh and invigorating look at our management policy.

The Quarterly: Apart from the accounting issues, what was behind the decision to give employees restricted stock rather than options? What effect has the decision had?

John Connors: The options program was originally designed to give employees enough money for retirement or a vacation home or to pay for their kids' education – goals that usually take 15 or 20 or 25 years to achieve. Yet because of the stock performance, people were making enough money to send 3,000 kids to college or build 30 vacation homes. Then the bubble burst, our stock declined by half, and roughly half our employees had loads of money but were sitting in the same offices and doing the same jobs as the other half, who would likely earn nothing from their options.

It was the worst of all possible worlds. At the same time, we were diluting the heck out of shareholders, who were telling us loud and clear that we should rethink the long-term value proposition of our options program. Of course, shareholders hadn't paid much attention to that dilution when it was outstripped by growth, but when growth lags behind and expectations change, that dilution looks a lot different.

In the end, we wanted a program that aligned employee and shareholder interests over the long term. So we came up with the stock award program, and we were very clear with employees about how many shares they would get, how the stock would have to perform for them to be worse off, and how the program would work over a multiyear period.

The reaction has been pretty positive, and I think we have a good model. We will have been wrong if Microsoft really outperforms the market and the market performs extraordinarily well over the next seven years – then a number of employees would have been better off with options. That was a bet we were willing to make. If you look at the market in the 14 months since we made the announcement, and the predictions of most market prognosticators, the bet is pretty good so far.

The Quarterly: Having tackled such an ambitious agenda in your tenure, what challenges are next for you?

John Connors: The big challenge is probably institutionalizing the finance function and the finance 2.0 model we have been developing. And I feel the company is in a good place right now; if I got hit by a bus, got fired, or decided not to work here anymore, someone could step in and he or she would be really successful. That's important to me because I will have worked here for 16 years in January, and I believe people should leave a job in better condition than it was when they started.

Second, while it's essential to be viewed as a leader in investor relations, treasury, tax, and corporate reporting, it's also rewarding to be viewed as a leader in creating great finance talent. Keith Sherin from GE was here last week, and that corporation is just a machine for producing great talent. In the Puget Sound area alone, the CFO at Amazon is from GE; the CFO at Washington Mutual is from GE. The company takes good people and makes them great, and its ability to export these business leaders is phenomenal.

I'm happy to say that we have also had some success along these lines. In the past six months, two of our business-unit CFOs have left for CFO positions at other corporations. It's tough to lose good people, but what a great thing it is for people who are five or six years into their careers here to be able to say, “I can become a CFO – either at Microsoft or somewhere else. I can be a business leader.”

And, on a personal note, I'd like to figure out how to have more time for my wife and our four kids so that I don't wake up someday and find that my kids are off to college and I'm too old to climb Mount Rainier again.

NOTES

1. Section 404 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 requires all public companies to give the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) an annual assessment of the effectiveness of their internal controls. In addition, the independent auditors of a corporation are required to review its management's internal-control processes with the same scrutiny as its financial statements.

2. Generally accepted accounting principles.

Reproduced from The McKinsey Quarterly, 2005 Number 1. Copyright © 1992–2005 McKinsey & Company, Inc.