1

The World was their Oyster: International Diversification Pre-World War I

Janette Rutterford

Bernstein (1996), in his history of risk, suggests that our forebears were relatively unsophisticated when it came to managing portfolio risk, or indeed quantifying it:

Throughout most of the history of stock markets – about 200 years in the United States and even longer in some European countries – it never occurred to anyone to define risk with a number. Stocks were risky and some were riskier than others, and people let it go at that. Risk was in the gut, not in the numbers. For aggressive investors, the goal was simply to maximise return; the fainthearted were content with savings accounts and high-grade long-term bonds. (p. 247)

Diversification, in the mid- to late nineteenth century, happened more through luck than judgment, as a means of enhancing income in the face of declining yields on British Government bonds. As overseas markets developed, with higher-yielding investment opportunities in their wake, so investors bought the securities on offer. Investment trusts and insurance companies, for example, bought bonds from different parts of the world, with very different risk characteristics, according to historical accident or opportunism. However, by the first decade of the twentieth century, British investors, both institutional and retail, had become more sophisticated in their approach to diversification. They were aware that holding a portfolio of international securities meant improved yields and increased capital safety, achieved by exploiting low correlation between different countries, markets, types of security and types of industry.

By World War I, recommended portfolios covered the entire globe, the reasoning being that, whilst one country, market or sector might suffer, the world as a whole would continue to grow in economic terms. Buying the global portfolio was deemed to be the most efficient portfolio strategy in risk-return terms. Investors clearly followed this advice since, by 1914, British investors as a whole had almost half of long-term negotiable portfolio capital invested outside their home country and were investing two-thirds of new money overseas (Edelstein 1982, p. 113; Davis and Huttenback 1987, p. 38). A significant number of individual investors had only limited exposure to British securities in their investment portfolios. By contrast, as Graham and Dodd (1934) observed of this period, “the idea of world-wide geographical distribution had never exerted a powerful appeal upon the provincially-minded Americans” (p. 311). Even today, the levels of diversification in US investors' portfolios “present a puzzle” (Statman 2004, p. 44).

DEFINING RISK AND RETURN

Today, investors are assumed to want to maximise investment return, generally agreed to be the total of income and capital gain over a particular period. The measure most commonly used to quantify risk is the standard deviation of returns. The relationship between individual securities is measured by the correlation coefficient. The less correlated the securities in a portfolio, the greater the benefits from diversification. Markowitz diversification optimises the risk-return trade-off by maximising return for a given level of risk, or minimising risk for a given level of return, taking into account each security's expected return, risk level, and correlation coefficient with every other security in the portfolio. The amount to be invested in each security will depend not only on its own risk and return characteristics but how it interacts with other securities. Naïve diversification, which assumes equal amounts invested in each security, achieves a less satisfactory risk-return trade-off than full Markowitz optimisation.

How did nineteenth century investors think about investment risk and return? With French investors called “rentiers” and their British equivalents “capitalists” or “annuitants”, the primary aim of these investors was to live off their capital. The vast majority of British investors came from a class which placed constancy of income as their number one priority, as did Jane Austen's Mrs Bennett, in the novel Pride and Prejudice, describing their new neighbour, Mr Bingley, to her husband, “A single man of large fortune; four or five thousand a-year. What a fine thing for our girls”.1 Capital gain was not relevant to investors who lived on their income until they died and passed on their income to their heirs.

Early government borrowing was in the form of annuities, which offered investors a guaranteed income until death. Undated British government bonds, known as Consols, provided investors and their heirs with a guaranteed income. Alternatives to government bonds were also analysed with a long-term perspective. Insurance companies were accused of never willingly selling investments and they clearly preferred long-term investments to short-term. A British actuary observed that he thought “it would be agreed that what a life office required was not so much a high yield as a permanent one. A railroad bond producing 4½ per cent for fifty years was obviously preferable to a first-rate industrial debenture yielding even 6 per cent or more for ten years, because by the choice of a long-term security the office could render itself independent of the general course of interest for perhaps the next forty or fifty years” (May 1912, pp. 151, 156).

These investors, when they thought of risk, thought of the risk of capital loss. For example, Bailey, in an 1862 paper addressed to insurance companies, laid out a set of investment “canons”. The first was that the main consideration should invariably be the security of capital; the second, that the highest practicable rate of interest should be obtained, but that this principle should always be subordinate to the previous one, the security of the capital (May 1912, p. 153). If the capital value was certain on repayment day, it was argued that price volatility between now and then could be ignored.2 Bailey also recommended mortgages and non-marketable securities as suitable investments for insurance companies because, being unquoted, prices would not fluctuate.

MANAGING RISK

Today's investment texts advise the use of statistical techniques to manage risk. Historical risk estimates are used, together with expected return fore-casts, to generate asset allocation strategies and portfolios that are optimal in the risk/return sense. Previous generations of investors decided on the appropriate risk level indirectly, by choosing a security with the required income yield and an acceptable level of risk of capital loss. For truly risk-averse investors, Three per cent government Consols were the risk-free benchmark, against which all other securities could be compared. “The higher the rate of interest, the worse the security” (Beeton, 1870, p. 26). The risk hierarchy moved up the scale from government-guaranteed bonds, through priority corporate securities, to shares on dividend-paying stocks. The key point was the desired level of yield. Once this had been determined, all that the investor could do was to minimise risk in a number of ways.3 The first was to avoid investing in categories of security that were considered too high up the risk scale, the higher yield being deemed not worth the risk of interrupted income and/or capital loss. The second was to spend time investigating each security in depth, by studying the accounts and reading newspapers, or by consulting advisers. The third method of reducing risk was to spread risk across different securities. Initially done as an ad hoc “extension” to a limited portfolio, by the early twentieth century a sophisticated global diversification strategy had been developed.

INTERNATIONAL INVESTMENT

International diversification happened partly by default as securities in new enterprises were offered to investors. Whole new industries sprang up, for example, canals, railroads, the telegraph, steam shipping, gas, electricity, bicycles, as well as gold mining opportunities in Australia and California, railways in Japan and South America, and ruby mines in India. In addition to private enterprise, governments and municipalities the world over turned to London to finance their debts. By 1914, there were 5000 securities listed on the London Stock Exchange, at that time the largest in the world, and the vast majority were foreign or Empire stocks. Currency risk was deemed irrelevant. As Capie and Wood (1974, p. 214) point out: “The years 1870 to 1914 were years of monetary tranquillity, the heyday of the classical gold standard. Britain was on the standard and more and more countries were joining it”. Loans were in sterling or backed by gold. Cotton, explaining to female investors in 1898 how to write a sterling cheque commented: “remittances in this way can be sent to almost every town in the civilised world” (p. 146).

There is general agreement that one motive for overseas investment was to improve income. For example, Michie (1986) observed that the increased investment in overseas mining shares was encouraged “both by the expanding press and declining interest rates on older more established forms of investment like mortgages and Consols” (pp. 149–50). In particular, during the last two decades of the nineteenth century and up to 1906, yields on Consols fell. The yield on Three per cent Consols reached a low of 1.96% in 1897 and New Groschen Consols issued in 1888 paid 2¾ per cent up to April 1903 and 2½ per cent thereafter (Harley 1976, pp. 101, 105). Wages did not fall to reflect the fall in investment income, so investors turned to overseas investments offering higher yields to bridge the income gap.

Colonial government bonds, such as those issued by the Indian government, were considered to be as low risk as home government bonds. “The security of the Indian Government is scarcely, if at all, inferior to that of the British Government itself; for where would be the prestige of the British name were we to allow our Indian empire to be wrested from us by any power whatever?” (Chadwicks' Investment Circular 1870, p. 52). Other overseas government and municipal bonds were clearly riskier than British or Colonial bonds, but offered highly attractive rates. For example, Chadwicks reported amongst new foreign issuers in London in 1870, the City of Boston, Massachusetts offering 5 per cent coupon at a price of 87 per cent of par, Russia offering 5 per cent at 80, the Mississippi Bridge financing paying 7 per cent and offered at 90, with Alabama paying 8 per cent and offered at 94½ . Japan came to the market for the first time in that year, with a 9 per cent offering at 98 (1871, p. 38). Such offers were very attractive in yield terms compared to Three per cent Consols.

Overseas government bonds came highly recommended – in preference to domestic equities – not just by sponsoring banks and brokers but also by investment authors. As Beeton's Guide observed: “as a rule, foreign stocks pay a higher rate of interest than other securities, and have this advantage over shares in companies – that only the capital invested can be lost” (1898, p. 54). However, as can be seen from the pricing of these bonds, they were not considered interchangeable. Beeton's Guide recommended that investors consider not the countries' willingness but their ability to pay and listed four risk categories: good security and low interest (including France, Belgium, Holland and Russia); middling security with higher interest (Argentine, Brazil, Peru, Egypt, and Turkey); doubtful security and high interest (Austria, Danube, Italy, Portugal and Spain) and finally those which had ceased to pay interest (Greece, Mexico, and Venezuela) (p. 26). Failure to pay did not deter investors who believed that, in the long run, countries would pay up. France's position as low risk might surprise given that 1870 was the year in which it was defeated by Germany. Chadwicks' also took a sanguine view of “country” risk as applied to France. Discussing the £10,000,000 debenture issued to indemnify the Germans, Chadwicks' commented: “Foreigners will act upon the wise faith that so great a nation and so rich a country will always pay and be solvent somehow – no matter what may be the temporary diffiulty” (1871, p. 50). The money was raised at 85 per cent, offering a 6 per cent coupon. Germany, in the same year, as victor, was able to raise money on better terms – five per cent interest at 96½. Although the French risk was higher, the additional yield was deemed more than sufficient to compensate. Even with delayed interest payments or capital depreciation, the return would, it was believed, more than exceed that on risk-free British government bonds.

Political or country risk was not always limited to overseas investment. Indeed, overseas investment could be a means of reducing avoiding political risk at home. Even the British were not immune. In the early part of the nineteenth century, before the passing of the Reform Act, anxious Tories, “withdrew their savings from consols and purchased American bonds, determined to secure a pittance in some foreign country upon which they could live when the wreck took place” (Jenks 1963, p. 80). By the beginning of the twentieth century, the British “burdened with a floating pauper population, and … subject to recurring waves of socialism” were being positively encouraged to export their savings: “Indeed, to-day there is no section of the globe in which invested capital stands in such imminent peril as it does in England. In the present Parliament legislation has been largely confined to efforts to disendow the property-holder and to endow Labour at Capital's expense” (Investment Critic 1908, p. 32).

EARLY DIVERSIFICATION STRATEGIES

Initially, there was no particular strategy underlying portfolio construction. Each individual security was judged on its own merits, and bought in what seemed an appropriate amount, given the size of the issue, the amount available at the time, and the over-riding view that most money should be invested in relatively safe securities. An early example is that of Samuel Greg. Rose (1979) argues that the cotton mill owner sought alternative investments to the vicissitudes of the trade cycle by investing £21,000 in Prussian bonds, £5,500 in French rentes, and £3,000 in Peruvian bonds during the period 1813 to 1819. However, for safety, he still kept the majority, 69% in 1824, in Consols. Diversification was also helped by requiring company directors to own shares in the companies on whose boards they sat, as Jefferys (1938) pointed out:

The multiplication of companies meant multiplication of directorates, and a man of wealth and reputation had no difficulty in obtaining a seat on the board of a company and at the same time was not expected to invest extensively in the company. Directors share qualifications tended to fall. If he wanted income, then distribution of investments was a sounder basis for this than concentration and a prerequisite of distribution was marketability of shares (pp. 208–9).

A cautious approach to diversification was adopted by insurance companies. A survey by May (1912) of the investment portfolios of four insurance companies in 1857 shows between 46% and 87% invested in mortgages, with up to 24% invested in railway bonds, mostly British. In addition to these traditional investments, Metropolitan Life held 5.5% in Turkish government bonds whereas Rock Life had invested 13.5% of its cash in Canadian bonds. In terms of yield, these overseas bonds yielded more than the less than 3½ % on Consols. May observed that this approach was not diversification, more the principle of “extension of securities”, and deplored this method of portfolio construction:

Since all of our assurance business is based on the law of averages one would naturally have thought that this principle would have been given full weight when considering the question of the investment of funds. I am afraid, however, that in the past very little attention was paid to this point; the ruling consideration appears to have been to endeavour to satisfy oneself as to the safety of the capital in each investment considered by itself (pp. 136–7)

The key driver for international diversification was the quest for higher yield. Individuals were often under more pressure than institutions to generate high incomes. As Chadwicks' Investment Circular remarked, in 1870, “As we all know, very many people are constantly on the lookout for good investments, and when we come to inquire what it really is they want, we often find that they are in search of ‘a safe five per cent’. Less than five per cent, they say, they cannot live upon.” Although acknowledging the British investor's preference for none but British securities, Chadwicks' Investment Circular then went on to argue that:

We are now too much alive to our own interests to place our trust in Consols alone; for indeed the British Government Funds cannot accommodate a tithe of the money that is always pressing forward for investment. Moreover, Railways, and even Foreign Stocks, have been found to pay better in the long run. We hold that, by a careful selection from the various media of investment, very remunerative returns in the shape of interest may be obtained; while, by a proper division of risks, not only may the security for the principal be rendered perfectly satisfactory, but there may be a good prospect that the invested capital will steadily increase in value (pp. 30–1).

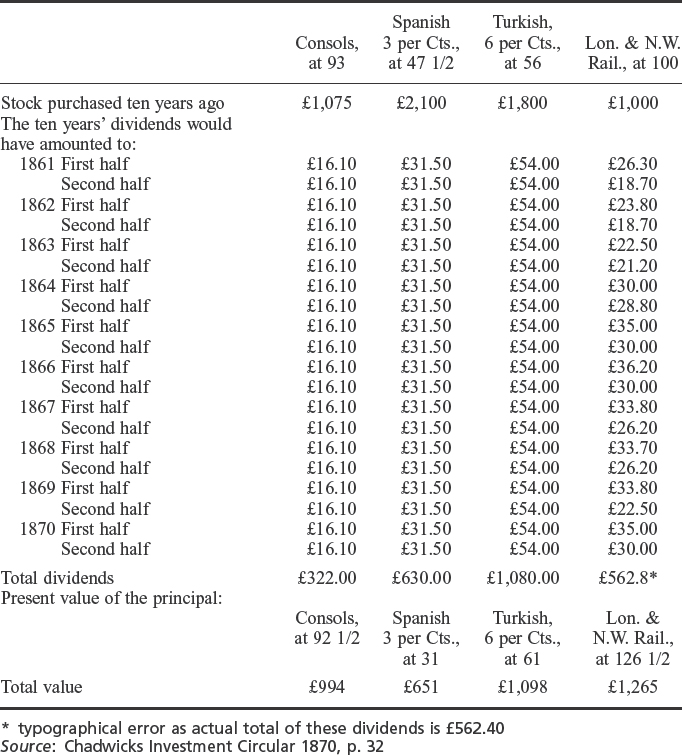

The authors provided an empirical example (Table 1.1) of how such “proper division” of risks might work. Choosing four securities then dealt on the Stock Exchange, of very different types, they showed that, had one invested £1,000 each in Three per cent Consols, Spanish Three per cents, Turkish Six per cents, and London and Western railway shares ten years before, the annual income yield would have ranged from 3¼ % for Consols to 10¾ % for Turkish bonds. They also took the change in principal value over the ten years into account, and showed how the total annual (simple interest) return on investment would have been 3 per cent for Consols, the same for Spanish Three per cents, 8¼ % per cent for Home Railway Stocks, and a sizeable 113/8; % on Turkish Six per Cents. They concluded: “The best mode of employing money would thus appear to consist in making a judicious selection amongst Home Railways and Foreign Stocks” (p. 32).

Table 1.1 Chadwicks' Investment Circular's diversified portfolio, 1870

Similar advice was also offered in Beeton's Guide to Investing Money with Safety and Profit, published in the same year. “If an investor wishes to secure a high rate of interest, he should divide his capital among a number of stocks that can be bought to pay a high rate of interest – the more the better. Supposing he has £500 to invest, let him invest £100 in each of the following – Turkish, Italian, Spanish, Egyptian, Guatemalan, or Argentine. By dividing his capital in this way, the investor reduces risk to a minimum, as it is unlikely that all these countries could stop paying their interest, although it is not unlikely that any one might do so”. Although appearing to limit investor choice to government bonds, Beeton's Guide allowed choice from a wide range of countries and types of security. For example, the author showed how a five per cent yield could be achieved in a number of different ways, by investing in two, three or more securities and a similar approach could be used to lock in any desired rate of interest. Five per cent could be achieved, for example, by buying half Russian bonds yielding 6% and half English railway debentures, yielding 4%. Alternatively, the same overall yield could be obtained from one-third Turkish bonds yielding 6½ %, one-third London and North Western Stock paying 5¼ %, and one-third in new Three per cent Consols yielding 3¼ %. A third method of gaining the magic five per cent was one-half in new Three per cent Consols, one-quarter in 7¾ % Argentine bonds and one-quarter in Brazilian 5¾ % bonds. The key point was that “it is only necessary to invest a small portion of the whole in a high dividend-paying stock to bring the rate up to 5% and that the greater part is invested in perfectly safe securities. The more the capital is divided the better, so that there may be a smaller amount in each security” (p. 56).

As the nineteenth century drew to a close, the problem of income became more acute, with yields on domestic securities falling. Private investors were forced into overseas securities to obtain higher, or even similar yields to those achieved in earlier years. Fortunately for them, supply was not wanting. Even cautious insurance companies substantially increased their overseas exposure. By 1912, May was able to comment that “the tendency at present was to invest almost exclusively abroad” and that “Canada, South America, China and Japan” were countries in which most assurance companies held securities (pp. 157, 163). Investment trusts were also adventurous in their investment policies. For example, by 1900, Foreign and Colonial Investment Trust held over 300 securities in its portfolio (McKendrick and Newlands 1999, p. 69). However, with increased overseas investment, there began to be a switch from ad hoc “extension” of securities to a more organised portfolio diversification strategy.

“SCIENTIFIC” APPROACH TO DIVERSIFICATION

A key development by the beginning of the twentieth century was a more “scientific” approach to global portfolio diversification. Instead of adding as many risky securities as required to generate the required yield, some investors began to realise that a more top-down approach to portfolio construction was desirable. By World War I, these investors were constructing international portfolios on a top-down basis, targeting a particular level of yield, and minimising capital risk through the choice of relatively uncorrelated securities. Historical analysis of returns, price volatility and correlation were all taken into account in the choice of the optimal portfolios. The need for rebalancing was also allowed for by ensuring that only marketable securities were considered for inclusion. By 1914, only the mathematical optimisation of Markowitz' model was lacking in terms of portfolio best practice. Nevertheless, investors chose more diversified, less correlated portfolios than is the case today, where, despite the implications of Markowitz' model, domestic securities dominate the portfolios of most investors, whether institutional or individual.

An early twentieth century example of the top-down approach is from a 1908 Pamphlet entitled “Women as Investors”. In a list of important principles and rules, the author recommends that women readers:

- “spread the capital over a number of concerns, and do not keep to one class of investment, so that if one or more are failures, there may remain others which are not.

- do not invest more than about one tenth of the capital in any one concern, unless personally occupied in its management and control” (p. 29).

More complex diversification strategies were actively promoted by the Financial Review of Reviews, a monthly magazine first published in 1905, and in textbooks such as “Investment an Exact Science”, published by the Financial Review of Reviews and written by a frequent contributor, Henry Lowenfeld. Lowenfeld (1911) recommended the following simple rules:

- “The capital must be divided evenly over a number of sound securities.

- All the stocks must be identical in quality.

- Each stock must differ, in respect of the risk to which capital invested in it is exposed, from every other stock in the same list” (pp. 7–8).

The key point behind the recommendations, as made by Crozier (1911), was that, by diversifying according to certain rules, “if this be accurately and skilfully done, there is no reason why the prudent investor should not be certain of getting a larger yield of income, with equal stability and security, from a Geographical Distribution of Capital than from any other mode of investment. It is thoroughly scientific in character” (my italics) (p. 118). May (1912) held the same view: “the investment of funds in relatively high yielding securities, carefully selected, not only gives more satisfactory return than that shown by the lower yielding stocks, but on the average gives greater security for the capital” (pp. 35–6).4

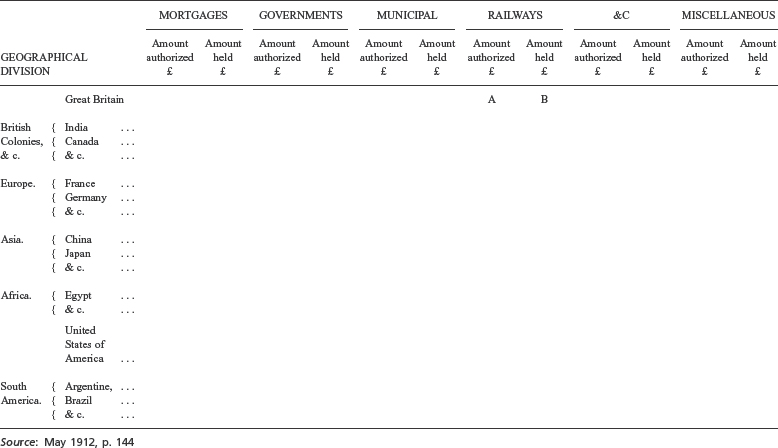

Both Lowenfeld, for individual investors, and May, for life assurance companies, produced schedules to encourage a full global diversification.5 Table 1.2 shows May's suggested schedule, with countries or regions on the left-hand side and types of security along the top. Table 1.3 shows that put forward by the Financial Review of Reviews.

Table 1.2 May's international portfolio template for life assurance companies, 1912

May recommended choosing countries, then types of securities and deciding an amount authorized for each type/country according to individual preference. Speaking in front of fellow actuaries, he felt that these decisions “were so much a question of individual opinion that I am afraid it would be quite out of place for me to put forward any scheme”. May divided the world into seven regions; Lowenfeld had nine regions by dividing Europe into North and South, as well as adding an “international” grouping, made up of companies operating on a global scale: international trusts, shipping, telegraph, marine insurance, etc. Such proposals recommended investing in each region of the world, and in a variety of types of security in each region, should funds permit. Crozier (1911), for example, suggested spreading the securities of any one country across a number of different types such as government, railways, shipping, banks and industrials. Different types of financial instrument were also allowed, although preference shares and debentures were preferred to equities, the latter deemed more exposed to market volatility (p. 113).

The thinking behind full global coverage was that, overall, the global population was growing, as was international trade. A global portfolio would therefore reap the benefits of this growth, whilst if one country suffered, another would benefit: “the wider the distribution of one's capital in every respect … the wider the distribution of risk run, and consequently the less likelihood of becoming stranded financially, since only a world-wide catastrophe … could arise to affect adversely the whole of the world's securities at one time” (Stacey 1923, pp. 38–9). Allen (1906), in the Financial Review of Reviews concurred: “While it is impossible to predict the future of any single investment, it is claimed that such a distribution of capital gives a means of forecasting with accuracy the result of a number of investments embracing the world's area, since the controlling factor of the value of such a group of investments being the whole world's trade, which according to previous assumption is unaffected as a whole by cycles of variation, the tendency is to the removal of the speculative element” (p. 27).

The attraction of global diversification was that it ensured that different types of risk were diversified away, improving the risk/return trade-off. Crozier (1911) recommended spreading investments across countries which varied in terms of different types of produce, different “trade currents”, supply and demand for investment capital, high interest rate and low interest rate, and so on. Specific security, sector risk and market risk, issues that are still not fully resolved today, were well understood:

Like the horses in a race, the number of stocks in an investment list are few in number; while the quality of the horses, their past records and present form, the jockeys that ride them, the length of the course, the nature of the ground, etc., correspond to the past history and present quotations of the stocks, and to the Money Markets, Stock Exchanges and Trade Currents which ride and dominate them (p. 120).

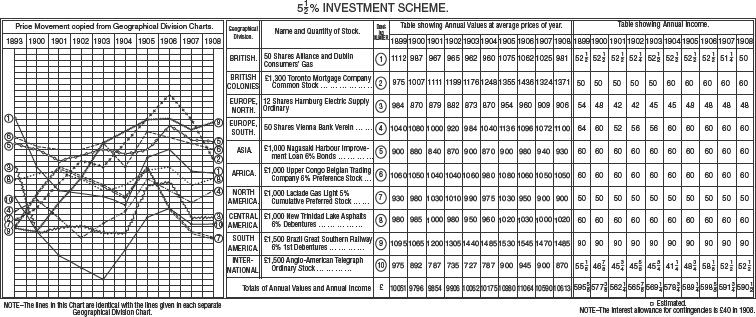

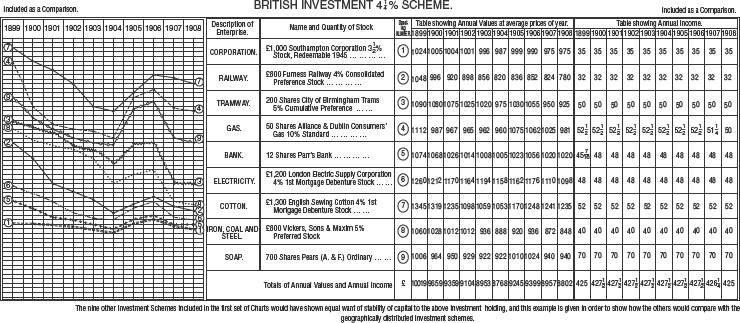

Table 1.3 Financial Review of Reviews' global portfolios for achieving 5½ % and 4¼ % annual yield

In terms of how much to invest in each security, the preferred number recommended for the private investors was ten securities, with equal nominal6 amounts to be initially invested in each. This number tallied nicely with Lowenfeld's nine regions of the globe plus one “international” sector. Withers (1908) argued that, with ten securities, individual investments were large enough for the investor to have the power to realise a substantial portion of his invested capital whilst being few enough to allow the investor to monitor his portfolio and watch for any investments which required replacing (pp. 40–41). Viscount Midleton, writing in the Financial Review of Reviews in 1908, complained that insurance companies, with hundreds of investments in their portfolios, had too many securities to be effectively managed and tended to review their portfolios “perhaps only when a quinquennial bonus has to be declared” (p. 11).

The Financial Review of Reviews, in their 1909 issue from which Table 1.3 is extracted, produced a number of portfolios of ten securities, each with a different income target, and each aiming to protect the capital value of the portfolio over a ten year period. For each required yield level, securities with similar initial yields were chosen from each geographical area. In the 5½ % Investment Scheme, for example, African Preference Stock, Central American Debentures and International Ordinary Stock are chosen, each offering an initial yield of between 5% and 6%. As “The Investment Critic”, commenting on these portfolios, observed, the British Investment Scheme, limited to British securities, targeted a lower yield of around 4¼ % “owing to the fact that England's accumulated wealth is greater than that of any other nation, capital invested in England commands a lower rate than it does in any other country” (p. 25).

The historical data shown in Table 1.3 are for the period 1899 to 1908, the longest and strongest period when overseas investments outperformed British investments pre-World War I. This ten-year historical analysis tallies with the approach of Chadwicks' Investment Circular, forty years earlier. Both use historical data as the basis of their recommendation for full global approach to diversification. Indeed, Lowenfeld argued that his sound principles of investment were based on “centuries of statistics and decades of practical experience” (1911, p. 15). Today, ten years, or more commonly five years, of historical data is still the most commonly-used method of modelling optimal portfolios for the future.

The portfolio analysis of the Financial Review of Reviews went further than an analysis of historical returns. It attempted to show graphically the impact of correlation on investment performance by plotting the price movements of the ten securities in each portfolio over the ten-year period. An article by Professor Chapman in the Financial Review of Reviews explained positive correlation or lack of it by saying that some industries were complements, such as the pen and pencil industries, whereas others were independent, such as the pen and boot industries (1908, p. 27). From Table 1.3, the positive correlation between stocks in the British Investment scheme is evident. These securities, it was argued, were subject to the same stock market influences, and had all depreciated over the period in question more or less in parallel. In contrast, authors such as Rolleston believed that, by diversifying internationally, as in the 5½ % Investment Scheme, the rises and falls of individual investments would “counterbalance each other and thus maintain an equilibrium in value” (1909, p. 38). These rises and falls could be explained by negative correlation between the securities. The counterbalancing effect was due to the fact that the securities were chosen to have equal “quality” or price volatility. In order to achieve this volatility balance, Lowenfeld required that yields on securities in any single portfolio should vary by no more than 1¼ % (1911, p. 12).

Using diagrams rather than maths, the portfolios proposed by the Financial Review of Reviews, and other authors of the time, took expected income, capital safety, price volatility and correlation into account, when determining recommended portfolios. The only theoretical difference between these investment strategies and those suggested by Markowitz, writing fifty years later, was that using an optimisation model might lead to more “efficient” investment portfolios, with amounts to be invested in each security chosen mathematically rather than via a “naïve” strategy of equal nominal amounts in each. However, the portfolios proposed by publications such as the Financial Review of Reviews, combined government bonds, corporate bonds and equities into single portfolios, rather than optimising within asset classes as is more common today.

DIVERSIFICATION IN PRACTICE

The main practical difference with today's approach to portfolio diversification is that the Financial Review of Reviews felt able to suggest optimal portfolios with only 10% in the British stock market, for example the 5½ % yield portfolio shown in Table 1.3. Such a strategy would now be viewed as too risky, even if the Markowitz model were to assume that most domestic securities, as was true in the first decade of the twentieth century for British investors, were inefficient in a risk/return sense. Today, the Markowitz model is rarely applied in a fully global context. Investors prefer to place the bulk of their money in domestic securities, using a constrained (and therefore sub-optimal) Markowitz optimisation process to determine their overseas investments. In the US, for example, pension funds held only 15% of their portfolios in non-UK securities in 2003; for UK pension funds, the equivalent figure was 30%.7 The UK benchmark APCIMS index, used for private investor portfolios, recommends that a maximum 25% be held in overseas securities.

These figures are in strong contrast to the situation in 1913 when, of all British-held long-term negotiable portfolio capital, foreign investment portfolio holdings accounted for 45% of the total (Edelstein 1982, p. 113). International diversification, as recommended by the Financial Review of Reviews and other influential people, such as Lowenfeld, May, academics and politicians – as numerous articles in the Financial Review of Reviews from 1905 to World War I testify – was clearly carried out in practice. The advice provided by the Financial Review of Reviews was also backed up with practical help. The periodical was published by a company called the Investment Registry which analysed stocks globally and, from these, prepared lists of acceptable stocks for each of the ten regions of the world. Investors could write in to the Financial Review of Reviews with their existing portfolio, and be given advice as to how to “internationalise” it or hand over responsibility for investment to the fund managers employed by the Investment Registry. The Investment Registry managed over £30 million in 1913, with over 9500 shareholders and customers (Financial Review of Reviews 1913, No. 98, p. 1006).

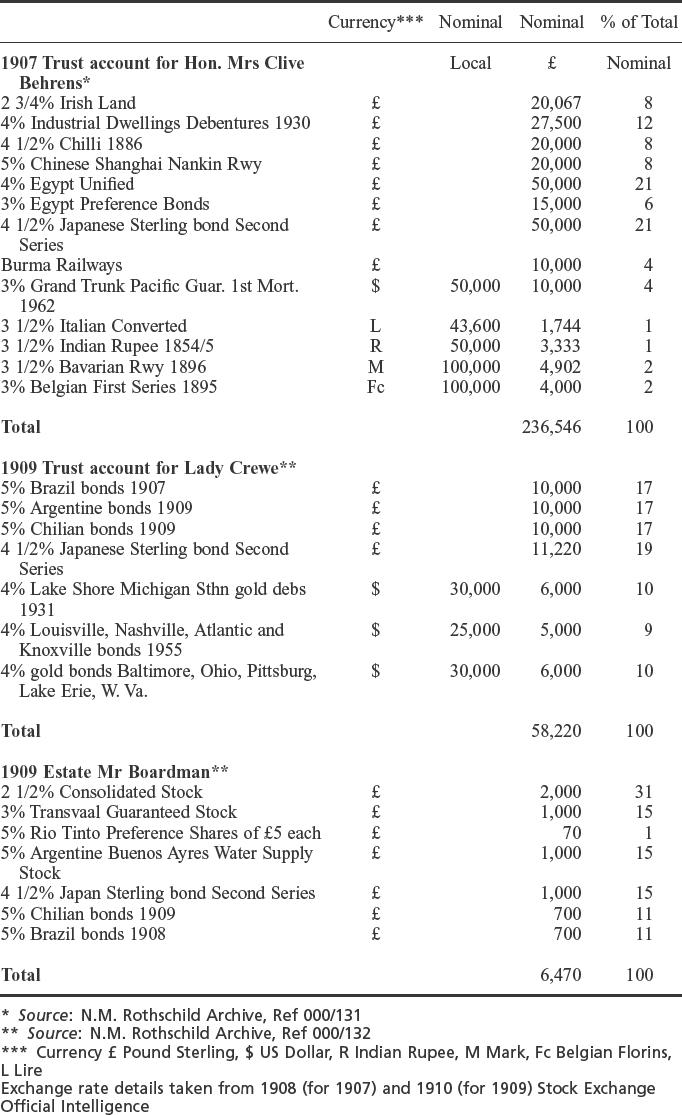

Merchant bank archives hold information on pre-World War I portfolios of relatively wealthy private individuals. Table 1.4 itemises the investments of three clients of N.M. Rothschild & Co. Limited from the period 1907 to 1909, drawn from a file containing details relating to the estates on death of Rothschild clients. All the estates in the archive file had internationally diversified portfolios, as do the three shown in Table 1.4, with balanced amounts, in nominal terms, spread across major geographical regions. In all three cases shown, the predominant currency of investment was the pound sterling, with the smallest exclusively in sterling-denominated assets. The largest portfolio, that of the Honourable Mrs Clive Behrens, was the most geographically diversified, with investments (of similar quality) in Europe, Asia, the Colonies, Africa, North and South America, Ireland and 20% in British negotiable assets. The second portfolio, that of Lady Crewe, had been switched from a portfolio fully invested in British Trustee stocks, primarily British railway debentures, to a portfolio that held no British securities at all. The smallest portfolio of the three, the estate of Mr Boardman, included 15% invested in Asia, 37% in Latin America, 15% in South Africa and 32% in British securities, although the South African securities were listed under British funds in the Stock Exchange Official Intelligence. All three portfolios concentrated on fixed interest securities, with the overseas securities all offering higher coupons than British Government Consols.8 By choosing high-yielding overseas securities which were less correlated with each other than were British securities, British investors, certainly those wealthy enough to bank with Rothschilds9, had pre-World War I investment portfolios which may, in practice, have been close to or exceeded in risk/return efficiency terms, today's constrained Markowitz portfolios.

CONCLUSION

This paper has looked at how pre-World War I British investors thought about and managed risk with respect to their investment portfolios, by examining contemporary periodicals and investment texts as well as examples of actual investment strategy. The paper argues that these investors sought to maximise yield, whilst minimising long-term income uncertainty and capital depreciation. International investment, encouraged by low yields available at home, by lack of currency risk, and by promotion in the financial literature and by some of the major merchant banks, took off in the mid-nineteenth century and reached a peak immediately prior to World War I.

Table 1.4 Examples of individuals' internationally diversified portfolios

Whilst being attracted to international investments, investors sought also to minimise risk in a number of ways. They concentrated on senior securities, such as debentures and preference shares, rather than risky ordinary shares. Where possible, they bought securities with which they had some connection, although this was possible only for the informed few. As an alternative approach to risk reduction, investors, encouraged by their advisers, turned to extensive global diversification, creating world-wide investment portfolios which they believed would benefit from global growth in population and trade, whilst being protected from difficulties in individual regions, markets, sectors and types of security. Such diversification was “naïve” in a Markowitz sense, since most investors, whether institutional or private, were encouraged to invest equal amounts in each security. However, the global reach of the portfolios ensured greater use of low correlation between sectors such as mining, railroads, retail stores, and countries such as Canada and Chile. Although in practice, many investors may not have been as global as the recommendations encouraged, evidence from archival research points to highly diversified portfolios. The equanimity with which British investors, both institutional and private, invested globally contrasts with the predominantly domestic bias of quantitatively oriented, modern-day institutional investors.

NOTES

1. Jane Austen 1934, p. 2, first published in 1813.

2. US investors agreed with Bailey, viewing undated Consols as more risky than long-dated government bonds. See William Cotton 1898, p. 13.

3. For further discussion of how investors, in particular British investors, valued securities before World War I, see Janette Rutterford 2004.

4. It is not clear whether George May believed that risk reduction would be achieved through the process of diversification itself or through finding more undervalued securities by allowing a broader range of investments.

5. Indeed, in 1912, the Financial Review of Reviews published George May's article in full, and published several articles in later issues discussing the role of diversification in insurance company strategy.

6. The emphasis on nominal rather than market value reflected the relative disregard for capital gain or loss compared with yield as a source of return. Some publications were unsophisticated as to the number of securities to choose and the difference between nominal and market values as far as diversification was concerned. For example, the weekly Investors' Review, in 1905, recommended a model trust with four securities of nominal value £100 each, with market prices varying from £102 2½ for Buenos Ayres Railway Debentures paying 5% nominal to £280 for Nobel Dynamite shares paying 10% nominal yield (November 11, p. 594).

7. Source: Callan Associates; The WM Company.

8. The Rothschild Archive, St. Swithin's Lane, London, 000/131 and 000/132.

9. There is some evidence that the “middle classes and females” preferred home firms, whereas the “elite” favoured foreign assets. See Samuel Pollard (1985), p. 499. Lance Davis and Robert Huttenback (1987) also point to higher than average overseas investments by the social elite and by businessmen, the former preferring empire and the latter “foreign” stocks (pp. 202–3).

REFERENCES

Allen, Sidney S. 1906. “ ‘Investment an Exact Science’ Reviewed.” Financial Review of Reviews, No. 3 (January): 24–28.

Austen, Jane. 1934. Pride and Prejudice. London: Everyman's Library.

B., W. 1908. Women as Investors. Birmingham: Cornish Bros.

Beeton, Samuel Orchart. 1870. Beeton's Guide to the Stock Exchange and Money Market. London: Ward, Lock, and Tyler.

Bernstein, Peter L. 1996. Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Capie, Forrest and Douglas Wood. 1974. “Money in the Economy, 1870–1939,” in The Economic History of Britain since 1700. R. Floud and D. McCloskey eds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chadwicks' Investment Circular, issued monthly by Chadwicks, Collier & Co., etc., London 1870–1975.

Chapman, Stanley J. 1908. “Investment Risks and the Geographical Distribution of Capital.” Financial Review of Reviews, No. 37 (November): 26–33.

Cotton, William. 1898. Everybody's Guide to Money Matters. London: Fredrick Warne & Co.

Crozier, J. Beattie. 1911. The First Principles of Investment. London: The Financial Review of Reviews.

Davis, Lance E. and Robert A. Huttenback. 1987. Mammon and the Pursuit of Empire: The Political Economy of British Imperialism, 1860–1912. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

De Foville, Alfred. 1908. “Geographical Distribution and French Investment Success.” Financial Review of Reviews, No. 27 (January): 20–24.

Edelstein, Michael. 1982. Overseas Investment in the Age of High Imperialism: The United Kingdom, 1850–1914. London: Methuen & Co. Ltd.

Graham, Benjamin and David L. Dodd. 1934. Security Analysis. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc.

Harley, C.K. 1976. “Goschen's Conversion of the National Debt and the Yield on Consols.” Economic History Review, Vol. 39, Second Series: 101–6.

Investment Critic. 1908. “Factors Determining the Value of Corporation Stocks.” Financial Review of Reviews, No. 36 (October): 25–32.

Jefferys, J.B. 1938. “Trends in Business Organisation in Great Britain since 1856, with special reference to the financial structure of companies, the mechanism of investment and the relationship between the shareholder and the company.” Ph. D. Thesis, University of London.

Jenks, Leland H. 1963. The Migration of British Capital to 1875. London: Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd.

Lowenfeld, Henry. 1911. “The Rudiments of Sound Investment.” Financial Review of Reviews, No. 63 (January): 5–17.

Markowitz, Harry. 1952. “Portfolio Selection.” Journal of Finance, Vol. 7, No. 1 (March): 77–91.

May, George E. 1912. “The investment of life assurance funds.” Journal of the Institute of Actuaries, Vol. 46:134–68.

McKendrick, Neil and John Newlands. 1999. ‘F&C’: A History of Foreign & Colonial Investment Trust. London: Foreign & Colonial Investment Trust PLC.

Michie, Ranald C. 1986. “The London and New York Stock Exchanges, 1850–1914.” The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 46, No.1: 71–87.

Midleton, Hon. Viscount. 1908. “British Life Assurance and American Models.” Financial Review of Reviews, No. 35 (September): 5–12.

Pollard, Sidney. 1985. “Capital Exports, 1870–1914: Harmful or Beneficial.” The Economic History Review, Second Series, Vol. 38, No. 4: 489–514.

Rolleston, Sir John F.L. 1909. “Scientific Investment in Daily Practice.” Financial Review of Reviews, No. 40 (February): 36–51.

Rose, Mary B. 1979. “Diversification of Investment by the Greg Family, 1800–1914.” Business History, Vol. 21, No.1: 79–95.

Rutterford, Janette. 2004. “From Dividend Yield to Discounted Cash Flow: A History of US and UK Equity Valuation Techniques.” Accounting, Business and Financial History, Vol. 14, No. 2: 115–49.

Stacey, H. 1923. Stacey's Guide to Stock Exchange Investment, London: The Basing Syndicate.

Statman, Meir. 2004. “The Diversification Puzzle.” Financial Analysts Journal, Vol. 60, No. 4 (July/August): 44–53.

Treble, J.H. 1980. “The Pattern of Investment of the Standard Life Assurance Company 1875–1914.” Business History, Vol. 22, No. 2: 170–88.

Withers, Hartley. 1908. “The Best Market for Capital.” Financial Review of Reviews, No. 36 (October): 33–41.