4. Innovations in Housing Finance

Homeownership rates in the United States reached an all-time high during the first six years of the twenty-first century, reaching across lines of class, ethnicity, and race. During the boom, American home buyers were offered a dizzying array of mortgage products, many with novel features: fixed or floating interest rates, rate lock-ins, rate resets, new choices of term and amortization, interest-only options, prepayment penalties, and easily dispensed home equity loans.

But, as we learned all too painfully, any victory laps for the financial and social policy achievements represented by wider homeownership were destined to be short-lived, as many new mortgage products failed with severe consequences. Overcomplexity and dangerous levels of leverage eventually swamped housing finance markets—and mortgage credit, as it turned out, was the canary in the coal mine signaling the broader financial crisis that was soon to follow.

An ocean of ink has since been spilled as analysts and pundits have weighed in on why our regulatory system consistently fails to detect and rein in asset bubbles. Now that our financial architecture has proven to be inadequate in today’s brave new world of intricate global connections, it is clear that we need a new wave of financial and policy innovation to prevent a repeat of recent history.

Gimme Shelter: The History of Innovation in U.S. Housing Finance

As demographic and social shifts have generated an ever-greater demand for housing, financial innovations have evolved to keep pace. The advances that expanded homeownership (and access to housing more generally) have been a lynchpin of greater economic and social mobility in industrializing economies. If the past offers any template for the future, it is not unreasonable to hope that new innovations emerging from the current financial crisis will restore and sustain historical trends of homeownership as a critical, but not unique, part of income and wealth creation.

The ideal of homeownership is entwined with the democratization of capital and our ideals of economic and social mobility. Being an owner has always been part of the American Dream. In the United States, ever since passage of the Land Ordinance of 1785 and the Land Act of 1796, the government had provided assistance to settlers in the form of low-priced land.1 Other legislation followed, such as the Preemption Act of 1841, which permitted would-be settlers to stake claims on most surveyed lands and purchase up to 160 acres for a minimum price of $1.25 per acre.

The Homestead Movement, which advocated parceling out land in the Midwest, the Great Plains, and the West to settlers willing to cultivate it, was consistent with Jeffersonian ideals; it was geared toward opening opportunities for would-be farmers in an age when this occupation was still considered the norm.2 Critical to this process was lending through mortgages. (These instruments had actually been in use since the twelfth century, when mortgages—literally, “dead pledges”—emerged as agreements to forfeit something of value if a debt was not repaid. Either the property was forfeited, or “dead,” to the borrower if he defaulted, or the pledge became “dead” to the lender if the loan was repaid.3)

In 1862, President Lincoln signed into law the Homestead Act. Under its terms, any citizen or person intending to become a citizen who headed a family and was over the age of 21 could receive 160 acres of land, eventually obtaining clear title to it after five years and payment of a registration fee. As an alternative, the land could be obtained for payment of $1.60 an acre after six months.

Lincoln had a strong ethical vision uniting capital ownership and labor productivity; his policies aimed to create, as Eric Foner writes, free soil, free labor, and free men. Lincoln spoke of “the prudent, penniless beginning in the world, who labors for wages for a while, saves a surplus with which to buy tools or land for himself ... and at length hired another new beginning to help him. This just and generous and prosperous system ... opens the way to all.”4 Enabling wider access to capital was a theme that echoed throughout many of Lincoln’s economic policies.

From homesteading to homeownership was a quick development, accompanied by the rise of urban industrial centers and the need to finance the communities within them. The origins of home finance grew out of two early-nineteenth-century institutional innovations: mutual savings banks and building and loan societies. Mutual savings banks were owned by their depositors rather than by stockholders; any profits belonged to the depositors, whose savings typically were invested in safe vehicles, such as early municipal bonds. Building and loan associations, by contrast, were explicitly created to promote homeownership. Building societies were corporations, with members as shareholders who were required to make systematic contributions of capital that were then loaned back for home construction.5

Meeting the Growing Demand for Housing Finance

Aspirations for homeownership that emerged in the nineteenth-century immigrant working classes eventually became an integral part of the American Dream. Over time, owning a home came to represent both physical and financial shelter. By the twentieth century, owning a home was a clear symbol of middle-class status, a goal that lower-income households strove for in order to supplement their incomes and economic security.6 The structural shift in demand that typically sparks financial innovations appears in the housing market in the form of the early twentieth century’s urbanization and rapid population growth.

The demand for capital rose steadily due to these long-term trends but occasionally spiked in the wake of critical events like Chicago’s Great Fire of 1871 or the San Francisco earthquake of 1906. Both of these episodes sparked new regulatory oversight of homebuilding and new innovation in commercial banking practices to boost housing market expansion.

After the San Francisco earthquake, A.P. Giannini, founder of the Bank of America (originally the Bank of Italy), reinvented commercial banking to support new customers entering agricultural, business, and housing markets—customers who had been rebuffed by the typical lending practices of the day. Giannini was determined to democratize commercial banking. From the first, he focused on small depositors and borrowers, opening banking to the masses. He advertised for depositors and made certain that local businessmen knew that the Bank of Italy was prepared to offer them its services in personal and business loans, as well as innovations in home mortgages.7 (For more on Giannini, see Chapter 3, page 65.)

The development of the modern mortgage industry, mortgage guarantee insurance, and homeownership as a policy goal was a natural extension of the spirit of the nineteenth-century Homestead Movement. But prior to Giannini and then the New Deal guarantee system, mortgage financing was limited in scope, with terms that seem unrecognizable and prohibitive today: high down payments, variable interest rates, and short maturities (five to ten years), with “bullet” payments of the full remaining principal due all at once when the mortgage’s term expired.8

Table 4.1. Types of Innovations in Housing Finance

Despite these financial constraints, homeownership grew from 10 million units in 1890 to 30 million units in 1930, especially during the boom of the 1920s. However, the financial capacity of the market was limited, as reflected in the high interest rates on loans—rates that were indicative of lending institutions’ relative lack of ability to hedge the interest rate risk and default risk associated with mortgages. Volatility (price fluctuations) and the absence of a nationwide capital market for housing (in which risks could be dispersed over a greater number of investors) produced high costs for home buyers and contributed to cyclical ups and downs. As existing residential real estate markets became saturated, the inability to finance new construction constrained growth.9

At the close of World War I, the “Own Your Own Home” movement was launched to reward returning veterans by helping them finance their homes. By 1932, Herbert Hoover oversaw the creation of the Federal Home Loan Banking System to reorganize the thrift industry and establish a credit reserve model based on the Federal Reserve.

In President Franklin Roosevelt’s first year in office, the housing market—like the rest of the economy—was in a downward spiral, with home mortgage defaults in urban areas around 50%. Many insufficiently capitalized private mortgage insurance companies failed during the Depression years. Sweeping government interventions were necessary to restore confidence and draw private investors back into the market. Since the federal government was not in the business of holding long-term mortgages, it created institutional responses to make the mortgage market function.10

The Roosevelt administration embarked on a major overhaul. Initially, the government offered federal charters to the existing private savings and loan associations and gave them the mission of providing funds for mortgage loans. It also insured their deposits, creating the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) to stabilize the banking industry and encouraging savers to place their funds in mortgage lending institutions. Mortgage insurance programs were instituted to reduce the risk faced by lenders. This era saw the establishment of the Home Owner’s Loan Corporation (later supplanted by Fannie Mae), the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), and the Federal National Mortgage Association (FNMA) to increase the supply of mortgage credit and reduce regional disparities in credit access. These moves, together with federal income tax provisions allowing homeowners to deduct mortgage interest and property tax payments, contributed to a sharp rise in homeownership—from 48% to 63% of all households between 1930 and 1970.11

The system of mortgage finance that resulted was characterized by long-term, fixed-rate, self-amortizing loans (provided mainly by savings and loan associations and mutual savings banks out of funds in their short-term deposit accounts). This was indeed the first mortgage revolution.12

Social policy and financial objectives converged to spur further innovation in the decades that followed. As millions of servicemen streamed home after World War II, they unleashed a vast pent-up demand for housing. Soon the Baby Boom was under way, and the great American migration to the suburbs commenced. The need for housing finance soon outstripped the capacity of depository institutions or the government. Gradually, capital market solutions began to emerge, including new innovations to enhance the liquidity of lenders. Fannie Mae was transformed into a private shareholder-owned corporation in 1968, and two years later, Freddie Mac was founded. Together these government-sponsored enterprises (complemented by Ginnie Mae, which remained within the federal government) vastly increased the liquidity, uniformity, and stability of the secondary market for mortgages in the United States. The traditional reliance upon thrifts and commercial banks as sources of mortgage credit changed; funding became increasingly available through securities backed by mortgages and traded in the secondary market.

The Savings and Loan (S&L) Crisis

One of the key pieces of regulatory residue left over from the Great Depression was the ability of the government to impose deposit rate ceilings on lending institutions. This rule, Regulation Q, remained in effect until it was finally phased out in the early 1980s. It eventually caused banks and thrifts to experience “disintermediation,” or sudden withdrawals of funds by depositors when short-term money market rates available elsewhere rose above the maximum rate those institutions were allowed to pay on deposits.

S&Ls (also known as thrifts) were therefore locked into using short-term deposits to fund long-term mortgages, a mismatch that plagued the industry through a series of later financial crises. Without alternative funding sources, a loss of deposits could restrict credit access to new home buyers. Thrifts were restricted from matching what the market was paying through new savings vehicles (such as mutual funds, Treasuries, or money market accounts).

By the 1960s, the ability of depository institutions to fund long-term, fixed-rate mortgages was compromised by inflation, which pushed up nominal interest rates and eroded the balance sheets of those institutions. The maturity mismatch problem came to a head during the late 1970s and 1980s, culminating in the liquidity crises and insolvencies that became collectively known as the savings and loan crisis.

The crisis came about due to poorly designed deposit insurance, faulty supervision, and restrictions on investments to hedge the interest rate and credit risks faced during this period. The sharp rise in interest rates in the late 1970s (caused by the appreciation of the dollar against other currencies) caused a twist in the term structure of interest rates (the yield curve) that generated losses. From 1979 to 1983, unanticipated double-digit inflation coupled with dollar depreciation led to negative real interest rates. As financial institutions extended their lending base and their capital ratios worsened, conditions weakened in the industry. Monetary policy tightened, short-term rates soared, loans were squeezed, and a crisis was underway.13 Regulatory restrictions on S&Ls amplified the crisis, and hundreds of institutions went under, at a distressingly high cost to U.S. taxpayers.

Securitization Changes the Face of Housing Finance

The S&L crisis crystallized a major structural challenge in U.S. mortgage markets. The danger inherent in funding short-term liabilities with long-term assets in markets with interest rate volatility became a lesson well learned.

Historically, lenders had used an “originate to hold” model for home mortgages: Institutions originated loans based on careful due diligence and then serviced and held the loans in their portfolios. But starting in the 1970s, securitization (an “originate to distribute” model) took hold. Under this new model, lenders packaged pools of loans into securities that were sold in the secondary market. Upon getting the loans off their balance sheets, lenders gained liquidity and were able to make additional loans at lower cost to consumers.

In 1970, Ginnie Mae issued the first mortgage pass-through security (granting investors an interest in a pool of mortgages and “passing through” the regular payments of principal and interest, providing a flow of fixed income). By the 1980s, Freddie Mac had introduced collateralized mortgage obligations (CMOs), which separate the payments for a pooled set of mortgages into “strips” with varying maturities and credit risks; these could be sold to institutional investors with specific time horizons in their investment needs and different risk preferences. It became common for firms to slice the risk associated with this type of investment vehicle into different classes, or tranches: senior tranches, mezzanine tranches, and equity tranches, each with a corresponding credit rating. Investors in these different tranches absorb losses in reverse order of seniority; because equity tranches carry a higher risk of default, they offer higher coupons in return.

Local and international institutional investors purchased these mortgage-backed securities (MBS), introducing new and broader sources of funding into the housing market. From 1980 to Q3 2008, the share of home mortgages that were securitized increased dramatically (see Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1. The mortgage model switches from originate-to-hold to originate-to-distribute.

Sources: Federal Reserve, Milken Institute.

The rise of securitization made mortgage credit and homeownership available to millions of Americans. Securitization, combined with deep and liquid derivatives markets, eased the spread and trading of risk.14

The momentum created by securitization truly caught fire when new information technology was introduced in the 1990s, vastly improving the ability of mortgage issuers to gather and process information.15 The costs of loan origination were drastically reduced, with greater accessibility of data on credit quality and the value of collateral. Today lenders share information with credit bureaus, title companies, appraisers and insurers, servicers, and others. It has been estimated that the mortgage industry increased its labor productivity about two and a half times with the proliferation of data processing and Internet services.16

Despite the power of the information technology that has been introduced into mortgage markets, it’s worth remembering that old adage “garbage in, garbage out.” These new tools are powerful, but their ultimate effectiveness is totally dependent on the accuracy and quality of the data inputs. During the housing boom, many lenders used information technology solely to increase volume, neglecting its capacity to help them more carefully sift through risk factors.

Notwithstanding the current mortgage crisis, the innovations of securitization and financial policy made mortgages cheaper and more accessible while fueling the broader housing markets.17 With fewer institutional and regulatory barriers to operation, the mortgage market became more efficient. Yet a critical ingredient was missing: the proper alignment of incentives. This would prove to be a fatal Achilles’ heel, since originators had nothing to gain by maintaining high underwriting standards on loans that were immediately sold into structured finance products in the capital markets. Harmonizing the interests of borrowers, originators, lenders, and investors is an issue that urgently needs to be addressed by future financial innovations in this market.

The Current Housing Crisis: What Happened and Why?

From the initial rumblings in the subprime market to the government’s unprecedented bailout programs, the turmoil in the U.S. financial sector sent shockwaves throughout the global economy beginning in 2007. Federal and state governments continue to struggle with appropriate legislative and regulatory responses. As of these writing, financial institutions, corporations, and individual households are still engaged in a massive wave of deleveraging. The capital markets are sorting out competing financing models—and the U.S. housing market remains in need of serious repair.

The genesis of the housing bubble emerged from the ashes of the dot-com bust. To alleviate the downturn, the Federal Reserve drastically reduced interest rates, and the era of easy credit was under way. Other nations with massive foreign reserves were drawn to invest in the United States, and, with Treasuries offering only meager returns, they began to eye mortgage-backed securities as a “safe” vehicle offering higher yields. The appetite for these securities proved to be insatiable, and the mortgage market was soon awash with liquidity.18

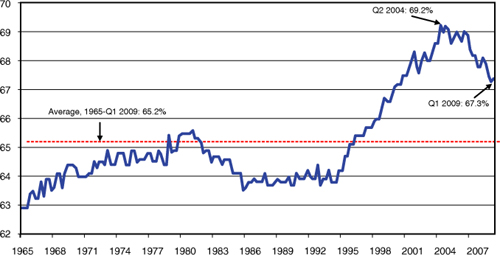

With mortgages so cheap and painless to obtain, homeownership reached a record high of 69.2% in mid-2004 (see Figure 4.2). Housing prices rose in accordance, posting sizable gains across the country—including huge double-digit year-over-year increases in frenzied markets such as Las Vegas, Los Angeles, Phoenix, and Miami. Real estate began to look like a surefire investment, open to almost everyone. But this game of musical chairs could continue only as long as home prices continued to climb and refinancing channels were open.

Figure 4.2. Credit boom pushes homeownership rate to historic high

Sources: U.S. Census Bureau, Milken Institute.

Thirty-year fixed-rate loans were once the only game in town, but less traditional home mortgage products started to appear in greater numbers in the early 2000s, with new variations on interest rate structures and amortization and payment schedules. Hybrid mortgages offered fixed rates for a short period of time, then reset periodically over the remaining term of the mortgage. These products have perfectly legitimate uses under the right circumstances, but they were too often handed out inappropriately, especially to consumers who—in a classic example of information asymmetry—didn’t fully understand the terms.

As the originate-to-distribute model took hold, lenders no longer had to retain all the functions associated with a mortgage. Not only could these institutions sell off the loan, but they could contract with outside originators and loan servicers. Soon there emerged a new class of originators who earned fees without retaining any credit risk. Between 1987 and 2006, mortgage brokers’ share of originations grew from 20% to 58%.19

With no ongoing responsibility for risk, originators had little economic incentive to ensure that borrowers were particularly creditworthy. As a result, subprime borrowers with shakier credit histories or inadequate income were able to obtain mortgages with little or no down payment—and that lack of equity eventually pushed them underwater when prices declined, increasing their incentive to default. This freewheeling environment saw the proliferation of complex mortgage products that embedded ever-higher levels of borrower, lender, and market risk. Subprime mortgage originations grew almost fourfold between 2001 and 2005, and total outstanding subprime mortgages increased at an average of 14% annually between 1995 and 2006.20

As described earlier, securitization did successfully increase liquidity and lower the cost of capital in the home mortgage market for decades. But during the boom, increasingly intricate and opaque securitized products appeared on the market, while the underlying valuation, credit analysis, and transparency of the underlying mortgages deteriorated. These complex securities were purchased by all manner of international and institutional investors, spreading the risk widely throughout the system.

Given the ready liquidity and the huge demand for mortgages triggered by historically low interest rates and rising home prices, lenders relaxed underwriting standards even further. Novel types of loans were not confined to the subprime market; some products offered to higher-end borrowers in the prime and near-prime markets carried such flawed incentives that they, too, would also eventually exhibit higher delinquency rates. Interest-only loans and loans requiring little or no down payment or income verification became commonplace.

Many buyers were attracted by the low initial monthly payments offered by adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMs), and lenders loved these products, too, since they shifted interest rate risk to borrowers. The largest share of ARMs went to subprime borrowers (as seen in Figure 4.3). Many borrowers and lenders operated under the assumption that housing prices would continue to rise indefinitely. Don’t worry about rate resets and your ability to afford higher monthly payments down the road, the thinking went—as long as home prices kept rising, magically creating more equity, borrowers would always have time to refinance before the interest rate on their ARMs jumped.

Figure 4.3. Largest share of ARMs goes to subprime borrowers

Sources: Mortgage Bankers Association, Milken Institute

The vast majority of subprime loans (almost 68% in 200721) were securitized, which means that a huge share of this credit risk was passing through the capital markets to investors. Complex and highly leveraged mortgage-backed products were developed to meet demand: collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), CDOs of CDOs, and even CDOs of CDOs of CDOs. The convoluted structures of these securities, and the investors’ lack of familiarity with the original loans, limited their ability to evaluate risk. Instead, they relied heavily on rating agencies to evaluate the quality of the underlying loans.

But an inherent conflict marred the rating process, in that agencies received fees from the very issuers they rated—yet another instance of misaligned incentives. Rating agencies relied on and applied historically low mortgage default rates to hand out AAA ratings to many questionable securities. The sterling ratings were illusory, of course. Too many of the underlying loans were held by highly leveraged borrowers who were operating on the false assumption that home prices would continue to rise forever. As we look to repair the system going forward, it is crucial to revamp the role and the compensation structure of the rating agencies.

Congress, too, bears some culpability. Beginning in 1992, it pushed Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to increase their focus on affordable housing. While the goal of expanding homeownership was undertaken with good intentions, it ultimately led to unintended consequences as these two government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) took on riskier portfolios. These two firms did not make loans directly, but they injected greater liquidity into a lending sector that was already becoming overheated. Even when problems became apparent, Congress and HUD regulators failed to rein in Fannie and Freddie until it was too late; both went into conservatorship in the fall of 2008, at a vast cost to taxpayers. Many observers have attributed this lapse in oversight to the fact that Fannie and Freddie spent millions on lobbying and campaign contributions over the years.

For anyone who was willing to look at historical patterns, it was plain to see that a serious housing bubble had formed. The ratios of median home prices to median household income and to rents had become seriously distorted—a fact that should have sounded a clear alarm bell to market participants and regulators alike. The increase in housing prices during the bubble years was simply too extraordinary to be sustainable (see Figure 4.4).

Figure 4.4. The recent run-up of home prices was extraordinary

Sources: Shiller (2002), Milken Institute

Some observers did correctly observe that a dangerous bubble had formed. In 2005, Paul Krugman warned that “the U.S. economy has become deeply dependent on the bubble.”22 That same year, The Economist estimated that the total value of residential property in developed economies had risen by more than $30 trillion in just five years to over $70 trillion—an increase equivalent to 100% of those countries’ combined GDPs. This supercharged growth not only dwarfed any previous house-price boom, but it exceeded the U.S. stock market bubble of the late 1920s (which grew to 55% of GDP). As The Economist called it, “it looks like the biggest bubble in history.”23 Economist Nouriel Roubini earned the nickname “Dr. Doom” for correctly predicting the crisis that was brewing. Hedge fund manager John Paulson took home $3.7 billion in 2007 compensation by, as The New York Times put it, “betting against certain mortgages and complex financial products that held them.”24 But surprisingly few on Wall Street shared Paulson’s prescience or his willingness to short subprime securities, betting on a decline in the price of these assets. Although it is easy to dismiss it today, the prevailing notion that home prices would not fall was persuasive to many people. Huge asset bubbles tend to encourage optimistic groupthink. Future efforts to contain systemic risk must take this behavior into account.

The collapse in home prices began in 2005 and accelerated dramatically by mid-2007. Forty-six states posted price declines in the fourth quarter of 2007.25 Delinquencies and foreclosures were skyrocketing, while new sales began to plummet. Many homeowners, especially those who bought late in the boom when prices were high, found themselves underwater. Other borrowers with ARMs had little or no equity in their homes and were unable to refinance when their payments reset.

Just as homeowners carried record levels of debt, financial firms were operating with unprecedented levels of leverage (see Figure 4.5). With too little capital supporting risky loans, neither homeowners nor institutions could absorb sudden, substantial losses.

Figure 4.5. Leverage ratios of different types of financial firms.

(Note: All ratios are as of December 2008 unless otherwise noted in parentheses.)

Sources: FDIC, OFHEO, National Credit Union Administration, Bloomberg, Google Finance, and Milken Institute

As it turned out, mortgage-backed securities were just the tip of the iceberg. In fact, trillions of dollars were at stake in the form of insurance coverage and the complex derivatives known as credit default swaps (CDSs) that were based on these securities. (CDSs are contracts that allow investors to hedge against defaults on debt payments.) Some financial firms even traded massive swaps on mortgage-backed securities in which they had no underlying stake at all. Because these trades were made over-the-counter and not through a central exchange, investors’ fears were exacerbated. Uncertainty and a loss of public confidence are the greatest enemies of any well-functioning financial market.26

Studies have shown that around 40% of the approximately $1.4 trillion of total exposure to subprime mortgages issued over the period 2005–2007 was held by U.S. commercial banks, securities firms, and hedge funds.27 Contrary to the conventional wisdom that prevailed during the bubble, overly complex, opaque securitization didn’t manage to disperse risk—in fact, tremendous risk was concentrated on the highly leveraged balance sheets of financial institutions and intermediaries. As the financial crisis took hold, lending effectively ground to a halt as liquidity dried up and firms hoarded cash. The fallout seeped into the general economy as credit spreads widened, provoking widespread fear and massive government interventions. The very nature of the new global economy caused ripple effects to travel far and wide, regardless of whether countries had great advances in financial innovation (as in the United States) or relatively lower levels of financial innovation (like Japan, Germany, France, Spain, or Italy).

The core macroeconomic trends that drove the crisis had been underway for quite some time. Massive asset bubbles, first in tech stocks and then in housing, formed in the context of a major decline in the U.S. savings rate. The monetary policies of central banks, particularly the Federal Reserve, were too loose for a long period of time, focusing on the danger of consumer price inflation while ignoring the problem of asset price inflation. And for a number of years, investors and consumers alike made bad decisions based on faulty asset prices derived from the bubble.

We believe that loose monetary policy, combined with the ready availability of funds because of global imbalances, inflated the bubble in property prices, which we consider to be the most important cause of the crisis. It was the bursting of this bubble that precipitated the problems with mortgage-backed securities.

Another important factor to recognize is the existence of the government safety net and the prospect of government bailouts for many financial institutions, which created moral hazard. This encouraged risk-taking by banks and institutions such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. In particular, they were willing to take on large amounts of leverage, which magnified their losses and made these institutions much more vulnerable in a downturn. With the exception of Lehman Brothers, the financial firms were indeed correct in their belief that the government would bail them out when they got into trouble. In the wake of such extraordinary government intervention, moral hazard of this type is likely to be an even more important problem as we move forward. Financial innovators urgently need to address this issue in order to diminish the systemic risk caused by excessive risk-taking.

To what extent did the recent crisis result from the failure of financial innovation? Some pundits were quick to claim that was the case, but in fact, it came about because so many individuals and institutions cast aside the fundamental principles that must be in place for innovations to succeed.

New financial products always create learning curves for issuers, consumers, and investors. Mitigating this problem requires special emphasis on designing the right incentives, requiring all parties to have “skin in the game,” and increasing transparency—all factors that were neglected during the housing bubble.

The recent crisis in the housing market was a wrenching turn of events, but in the big picture, financial markets are laboratories that are constantly undergoing renewal—and they will eventually recover and adjust.

Avoiding the Mistakes of the Past

It’s said that those who do not understand history are doomed to repeat it. In order for capital to flow again, we must identify solutions that resolve past mistakes. We should avoid the following pitfalls:

• The misperception that asset prices will always continue to rise and the false sense of security built on that belief. During the dot-com boom, investors were swept up in a mania, buying stocks of companies with no proven track record as they chased an entire sector on a wild ride upward. The resulting correction was exponentially more painful because the frenzy had become so widespread.

The same events played out just a few years later in the housing market. As long as prices rose, the originate-to-distribute model seemed to convey little risk. Borrowers thought they could always refinance and capitalize on their increased equity. Investors in mortgage-backed securities relied on rating agency evaluations of the loan pools—but rating agencies didn’t account for the possibility of a price correction in their models and assumed the number of defaults in any pool would be small due to diversification.

But what goes up can go down. Regulators and the financial sector alike must take a clear-eyed view of the sustainability factors behind rising markets and break the cycle of tunnel vision that seems to take hold when asset bubbles are forming. The lure of the profits to be made when there is a huge demand for a product is a powerful thing, but an unrealistic comfort with risk can be dangerous for the stability of the financial system.

• A lack of transparency in mortgages and in securitized pools. As home prices skyrocketed, many consumers took out second mortgages, often without informing the first lien holder. At a Milken Institute Financial Innovations Lab held in October 2008, Tom Deutsch of the American Securitization Forum provided some startling statistics on 2006 residential mortgage-backed securities. While expected performance of loans within a securitized pool may have been based on a traditional 80% loan-to-value (LTV) ratio, the combined LTV (CLTV) was often closer to 90%. In the subprime market, the first lien LTV averaged 88%, and only 55% of loans had full documentation. In many cases, the full CLTV could not be determined, as the second liens were “silent seconds.” The vast majority of these mortgages were packaged into CDOs with less collateral than recorded.28

Once the loans were securitized, investors had no way of knowing the true composition of the pool. To their and the market’s detriment, they did not pursue trying to uncover this information, but relied too heavily on the opinions of rating agencies. When delinquencies and defaults began to climb, the lack of transparency became even more problematic. Borrowers looking for loan modifications often had a hard time discovering exactly with whom they should be negotiating. Murky pools of assets could not be sold, and banks lost confidence in each other’s balance sheets. This asymmetric information about counterparty risk led to liquidity hoarding and a breakdown of the interbank credit market.

Securitization has already proven it can work, but increased transparency will be key to rebooting the market.

• Misaligned incentives. During the housing boom, incentives became misaligned at several points, reducing the likelihood of positive outcomes. When risk is too easily passed along, it can snowball. When borrowers were not required to make substantial down payments, thus giving them an equity stake in a home from the very beginning, they tended to take on loans that were too large to handle. Mortgage brokers were paid fees for originating a greater volume of loans, not for originating appropriate loans to creditworthy borrowers. Lenders simply sold off loans in the secondary market without retaining an interest, thus losing all incentive to apply more prudent underwriting standards. Securitization pools were rated by agencies that were paid by the very institutions that issued the securities in question, leaving them inclined to simply please their clients by issuing favorable grades. Clearly, the incentive structure needs to be revisited at every stage of the game. If every participant retains a slice of risk, it will discourage recklessness.

• Ineffective regulation. Regulators have been wholly inadequate in the face of major asset bubbles. Gaps and overlaps between U.S. regulatory agencies left the government with no consistent, strategic approach to addressing the emerging crisis.

Moving forward, regulatory efforts should focus more intensely on containing systemic risk, strengthening capital requirements for banks, promoting greater transparency in the market, and modifying incentive structures to discourage excessive risk-taking. And regulators, like institutions, should be held accountable if they fail to perform their responsibilities. More effective enforcement of the regulations that were already on the books could have mitigated the crisis. The convoluted U.S. regulatory structure itself must be addressed if we have any hope of taking a more holistic, integrated approach to addressing asset bubbles and systemic risk.

• The dysfunctional role of ratings agencies. The government is making efforts to bring greater competition among rating agencies by designating other firms Nationally Recognized Statistical Rating Agencies. More generally, the government should avoid encouraging investors from relying excessively on ratings from such firms when making investment decisions.

Beyond the Crisis: Finding the Way Forward

There is nothing quite like a crisis to focus the financial innovation process. A major transformation of mortgage products and markets emerged out of the Great Depression. Similarly, the most recent systemic crisis (although it was an event of far smaller magnitude) is generating long-overdue debate about the role financial innovation can play in improving housing finance and preventing future market failures.

Many of these new ideas focus on capital market solutions: fixing what went wrong with the originate-to-distribute model and proposing ways to revive the securitization market. Others center on devising new ways to expand access to affordable housing in the current environment with lower risk.29

Capital Market Solutions

Rebooting securitization is the first step toward restoring the health of the mortgage market. It will require a return to fundamental analysis, due diligence, and sound underwriting, plus a new commitment to transparency and full disclosure about structured finance products. Additional data reporting is needed for disclosure on the vast number of loans in residential mortgage-back securities, including regular reporting of performance over time, full information on second liens, and loan comparisons. Requiring lenders to retain a certain share of each loan or even making provisions for possible repurchase obligations might also make structured finance more viable in the future.

Covered bonds, a financial innovation that dates back to eighteenth-century Prussia (pfandbriefe), are widely used in Europe (in fact, they are one of the largest sectors of the European bond market), and they are gaining favor as a way to help resolve the current crisis in the United States. These securities are issued by banks and backed by a dedicated group of loans known as a “cover pool”; each country’s laws outline the requirements for inclusion. If the issuing bank becomes insolvent, the assets in the cover pool are set aside for the benefit of the bondholders. Covered bonds closely resemble mortgage-backed securities, but the underlying loans remain on the balance sheet of the issuing bank. The bank therefore retains the control necessary to change the makeup of the loan pool to maintain its credit quality and to change the terms of the loans. MBS, on the other hand, are typically off-balance-sheet transactions in which lenders sell loans to special-purpose vehicles that issue bonds, thus removing the loans (and the risk) from the lender.30

Another idea that provides greater flexibility in managing mortgage risk hails from Denmark. In this model, when a lender issues a mortgage, it is obligated to sell an equivalent bond with a maturity and cash flow that exactly matches the underlying home loan.31 The issuer of the mortgage bond remains responsible for all payments on the bond, and, in an interesting twist, the mortgage holder can buy back the bond in the market and use it to redeem their mortgage. When interest rates rise and home prices fall, borrowers are empowered to reduce the amount they owe as bond prices fall.

In the Danish model, the bond’s terms match the interest rate and maturity of the loan. Bonds are collateralized with pools of identical mortgages: generally fully amortizing, fixed-rate, 30-year loans with recourse and issued with an 80% LTV ratio. The issuer keeps the mortgage on its books, and if the borrower fails to pay, it buys the mortgage out of the pool at the lower of par or market price. Originators retain the credit risk, leaving the investors to bear only interest-rate risk. This approach combines characteristics of both covered bonds and securitization. Like standard covered bonds, the Danish instruments keep credit risk with the loan originators. Similar to securitization, the system creates tradable instruments, facilitating liquidity.

All bonds are tradable and transparent; the price can be tracked daily. Borrowers can monitor movement and, if interest rates rise, can take advantage of the buyback option. This enables borrowers to repurchase their own loans, providing flexibility. If a mortgage’s rate rises, the corresponding bond declines in value, allowing the borrower to purchase it at a reduced rate and gain equity in the home. Borrowers can then obtain a new, smaller mortgage with a higher coupon. This approach limits negative equity in periods of declining home values. The buyback option is exercised frequently: In the period 2001–2005, as yields fell from 6–7% to 4–5%, almost 100% of mortgages were prepaid and refinanced. It is interesting to note that while Denmark has been experiencing a downturn and falling home prices, it has not undergone the waves of defaults and foreclosures seen in the United States. During the global credit crisis, the country’s mortgage banks continued to sell bonds and issue mortgages at virtually the same pace as before.32

Affordable Housing Solutions

The fact that we experienced specific mortgage product failures (such as negative amortization mortgages and ARMs that created perverse incentives to default) does not negate the overall social objective of making decent housing affordable to all.

Currently, homeownership in the United States is an all-or-nothing proposition: You can rent, with 0% ownership, or you are on the hook for 100% of the risk and reward. Shared equity is a concept that implies reduced assets in exchange for reduced liability. One approach attempts to balance wealth generation for individual owners with the goal of preserving affordable housing. Some form of subsidy, either a tax benefit or direct subsidy, reduces the price of the home in exchange for a share of appreciation. There may be limits on the resale of the property and/or the appreciation of housing values. An alternate approach is the private-sector shared equity model, in which investors provide a share of the housing cost in exchange for a portion of appreciation. Both approaches foster access to homeownership at reduced levels of debt, while lenders reduce their risk by maintaining a share of ownership.

Three models generally make up the shared equity or fractional equity approach: limited equity cooperatives, community land trusts, and deed-restricted housing. These and other products on the drawing board have the potential to mitigate the blight and disrepair left behind in so many American neighborhoods by the recent wave of foreclosures. They could be sustainable and durable strategies for ensuring occupancy, promoting ongoing maintenance, and avoiding further foreclosures.

One of these models, the community land trust (CLT), involves establishing a nonprofit organization to hold land, with the mission of making any housing built on that land perpetually affordable to the designated community. CLTs are often used to extend homeownership in times of rising housing costs by keeping the rights to the underlying land in the hands of a separate entity and not passing along appreciated values to new purchasers. Currently, CLTs are operated or being established in roughly 200 communities in the United States33; there were 5,000–9,000 units as of 2006.34

Similarly, land banks attempt to lower housing costs through addressing the issue of land aggregation and development.35 A land bank enables state and local governments to acquire, preserve, convert, and manage foreclosed and other vacant and abandoned properties. By permitting the relevant agency (public or nonprofit) to aggregate and obtain title to these properties, the model creates a useable asset that can reduce blight, generate revenue, and facilitate affordable housing. It is thus a solution to both the affordable housing challenge and the foreclosure challenge.

Another model is the shared-equity mortgage, in which the lender agrees as part of the loan to accept some or all payment in the form of a share of the increase in value (appreciation) of the property.36 The shared-equity mortgage is a deferred-payment loan that spreads risk more effectively and increases affordability. In lieu of monthly payments, borrowers repay a lump sum upon termination.37 If the value of the house has risen, that sum represents a share of the appreciated value, greater than what would be owed under a traditional mortgage. But if the value declines, the borrower pays back only the original principal. The borrower has saved monthly payments as well as interest expenses; the lender loses the periodic interest payments but gains upside if the house increases in value. In effect, the lender has obtained equity in the property.

A related variation is the home equity fractional interest security (HEFI), designed by John O’Brien of the University of California, Berkeley, Haas School of Business. This fractional ownership arrangement would allow the homeowner to purchase only a certain percentage of a home while bringing in a passive coinvestor to finance the rest. This coinvestor shares in the potential gains and losses as the home price rises or falls. In the short term, this model could be used to head off foreclosures. For distressed homeowners, the proceeds from the HEFI security would be used for partial satisfaction of an existing lien or consideration for forbearance or mortgage restructuring by an existing lender. As O’Brien describes it, “The HEFI security represents a passive investor interest in a home—analogous to a share of stock, which represents a passive investment in a company. Institutional investors, such as those who manage pension and endowment funds, are interested in HEFIs to achieve diversification beyond stocks and bonds.”38

Attracting Private Capital Back into the System

Until the recent financial crisis, the private sector played a major role in funding residential real estate. But in the wake of the mortgage-market meltdown, the U.S. government has increasingly replaced the private sector as the major source of real estate funding.

Lending institutions have curtailed credit to the real estate sector as they recapitalize their balance sheets, and investors have cut back on purchases of mortgage-backed securities. At the same time, the securitization of mortgages by private firms has collapsed along with private-investor participation. Much of the funding now available for real estate is being provided by the government through its control of Freddie Mac, Fannie Mae, the FHA, the Veterans Administration (VA), and Ginnie Mae, and through purchases of mortgage-backed securities by the Federal Reserve. Most of the funding, moreover, currently goes only to the most creditworthy individuals.

This dramatic shift in funding poses a major problem that has yet to be addressed: a growing gap in the availability of credit to the real estate markets. The government has been focused on stemming the tide of home foreclosures through various loan modification efforts while also providing its own credit to the housing sector. But these actions are not designed to get real estate markets functioning normally again, and, in any event, the financial resources of the government are much smaller than those of the global capital markets and cannot sustain the financing of growing housing demand. Sole dependence on the Federal Reserve and other public entities or GSEs to support the real estate sector after the recession could threaten national economic growth and stability. The government’s stabilization and emergency stimulus plan should be supplemented with a plan to address the restoration of the historical partnership with private investors that was a major policy innovation of the past century. This is essential to promote a well-functioning financial system and sustainable and stable long-term economic growth.

Conclusions

With foreclosure and delinquency rates still at sky-high levels and more than one-fifth of U.S. home mortgages under water,40 scorched housing markets are still struggling to recover as of this writing. In this chapter, we’ve outlined the factors that led to spiraling prices (including lax monetary policy, excessive leverage, and irrational optimism) and market failures (including overly complex products, the ability of lenders to pass along risk, a lack of transparency, and the failure of rating agencies). While all these factors were dangerously distorting the market, U.S. regulators failed to take action. This is partly due to the procyclicality of regulation (the tendency for regulation to be loose during good times but much more stringent in financial downturns). It’s also due to a lack of accountability and the convoluted, overlapping structure of the various enforcement agencies. The federal government is currently debating ways to remedy this structural deficiency by streamlining the regulatory structure and creating a greater focus on systemic risk.

Progress is often born out of moments of crisis. Just as sweeping financial and policy innovations emerged from the Great Depression to provide housing opportunities, new financial products and policies are already being developed in response to the current housing meltdown. We’ve examined alternatives that could reduce the number of foreclosures in times of declining real estate prices, and distribute risk among loan originators and the ultimate owner of the mortgage while giving upside potential and downside protection to homeowners. It is crucial to reboot the market for mortgage-backed securities, but this time with greater transparency, following models used in the corporate bond market.

Historically, real estate has proven to be one of the riskiest asset classes. Safely facilitating access to affordable housing is a continuing objective of financial innovation. The expansion of homeownership may be a radioactive topic in the wake of the meltdown, but it’s a task that has never been more urgent. Stabilizing the housing market is critical to stabilizing the broader economy.

Endnotes

1 Joyce Appleby, Liberalism and Republicanism in the Historical Imagination (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992).

2 Richard Rosenfield, American Aurora: A Democracy-Republic Return (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1997).

3 Jim Duffy, “What Is a Mortgage, and Why Does It Matter?,” FHA Mortgage Blog (16 September 2009). Available at www.myfhamortgageblog.com/2009/09/what-is-a-mortgage-and-why-does-it-matter/; accessed September 28, 2009.

4 Quoted in Eric Foner, Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1970). See also Foner, Politics and Ideology in the Age of the Civil War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1980).

5 James R. Barth, Susanne Trimbath, and Glenn Yago, The Savings and Loan Crisis (Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2004).

6 Margaret Garb, City of American Dreams: A History of Home Ownership and Housing Reform in Chicago, 1871–1919 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005).

7 Felice Bonadio, A. P. Giannini (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994).

8 Marc A. Weiss, “Marketing and Financing Home Ownership: Mortgage Lending and Public Policy in the United States, 1918–1989,” in Business and Economic History 2, no. 18 (1989):109–118. See also William W. Bartlett, Mortgage-Backed Securities: Products, Analysis, Trading (New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1989).

9 Ben. S. Bernanke, Housing, Housing Finance and Monetary Policy, speech delivered at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s Economic Symposium, Jackson Hole, Wyoming (21 August 2007). Text available at www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/bernanke20070831a.htm.

10 William S. Haraf and Rose-Marie Kushmeider (eds.), Restructuring Banking and Financial Services in America (Washington: American Enterprise Institute Publishing, 1988).

11 Congressional Budget Office, “The Housing Finance System and Federal Policy: Recent Changes and Options for the Future” (October 1983): ix.

12 Richard K. Green and Susan M. Wachter, “The Housing Finance Revolution,” paper presented at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s 31st Economic Policy Symposium: Housing, Housing Finance and Monetary Policy, Jackson Hole, Wyoming (31 August 2007).

13 Barth, Trimbath, and Yago, The Savings and Loan Crisis (Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2004).

14 Andreas Lehnert, Wayne Passmore, and Shane Sherlund, “GSEs, Mortgage Rates, and Secondary Market Activities,” Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics 36, no. 3 (April 2008): 343–363.

15 Eric S. Belsky, Karl E. Case, and Susan J. Smith, “Identifying, Managing, and Mitigating Risks to Borrowers in Changing Mortgage and Consumer Credit Markets,” Joint Center for Housing Studies, Harvard University (2008).

16 Mark S. Doms and John Krainer, “Innovations in Mortgage Markets and Increased Spending on Housing,” (working paper no. 2007–05, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, 2007): 4–5.

17 Heitor Almeida, Murillo Campello, and Crocker Liu, “The Financial Accelerator: Evidence from International Housing Markets,” Review of Finance 10, no. 3 (2006): 321–352. See also Paul Bennett, Richard Peach, and Stavros Persitiiani, “Structural Changes in the Mortgage Market and the Propensity to Refinance,” Federal Reserve Staff Report no. 45 (September 1998).

18 The research and analysis throughout the section is based on James R. Barth, Tong Li, Wenling Lu, Triphon Phumiwasana, and Glenn Yago, The Rise and Fall of the U.S. Mortgage and Credit Markets: A Comprehensive Analysis of the Market Meltdown (New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2009).

19 Wholesale Access and Milken Institute data, as cited in Barth, et al., The Rise and Fall of the U.S. Mortgage and Credit Markets: A Comprehensive Analysis of the Meltdown.

20 Ibid.

21 Ibid.

22 Paul Krugman, “That Hissing Sound,” New York Times (8 August 2005).

23 “In Come the Waves,” The Economist (16 June 2005).

24 Jenny Anderson, “Wall Street Winners Get Billion-Dollar Paydays,” New York Times (16 April 2008).

25 Freddie Mac data, as cited in as cited in Barth, et al., The Rise and Fall of the U.S. Mortgage and Credit Markets.

26 Ibid.

27 David Greenlaw, Jan Hatzius, Anil K. Kashyap, and Hyun Song Shin, “Leveraged Losses: Lessons from the Mortgage Market Meltdown,” U.S. Monetary Policy Forum Report no. 2 (2008).

28 Betsy Zeidman, James Barth, and Glenn Yago, “Financial Innovations for Housing: Beyond the Crisis,” Milken Institute Financial Innovations Lab Report (November 2009).

29 This discussion draws from Zeidman, Barth, and Yago, “Financial Innovations for Housing: Beyond the Crisis.”

30 PIMCO, “Bond Basics: Covered Bonds.” Accessible at http://europe.pimco.com/LeftNav/Bond+Basics/2006/Covered+Bond+Basics.htm.

31 Alan Boyce, “Can Elements of the Danish Mortgage System Fix Mortgage Securitization in the United States?” Presentation at the American Enterprise Institute, Washington, DC (26 March 2009).

32 “A Slice of Danish: An Ancient Scandinavian Model May Help Modern Mortgage Markets,” The Economist (30 December 2008).

33 National Community Land Trust Network, “Overview.” Accessible at www.cltnetwork.org/index.php?fuseaction=Blog.dspBlogPost&postID=27.

34 John Emmeus Davis, “Shared Equity Homeownership: The Changing Landscape of Resale-Restricted, Owner-Occupied Housing,” National Housing Institute (2006).

35 Don T. Johnson and Larry B. Cowart, “Public Sector Land Banking: A Decision Model for Local Governments,” Public Budgeting and Finance 17, no. 4 (1995): 3–6.

36 John Emmeus Davis, “Shared Equity Homeownership: The Changing Landscape of Resale-Restricted, Owner Occupied Housing,” National Housing Institute (2006).

37 Andrew Caplin, Noel B. Cunningham, Mitchell Engler, and Frederick Pollock, “Facilitating Shared Appreciation Mortgages to Prevent Housing Crashes and Affordability Crisis,” The Brookings Institution (2008).

38 John O’Brien, “Revolutionary Help for Homeowners,” Christian Science Monitor (26 November 2008).

39 Nigel G. Griswold and Patricia E. Norris, “Economic Impacts of Residential Property Abandonment and the Genesee County Land Bank in Flint, Michigan,” MSU Land Policy Institute Report 2007–05 (April 2007).

40 Daniel Taub, “Fewer U.S. Homeowners Owe More Than Properties Are Worth,” Bloomberg (9 November 2009).