Tigers are revered in East Asia as both religious and cultural icons. They are the national animal in some countries and appear on the flags of others. Dominant throughout consumer culture, their likeness peddles everything from airlines to candy. For all their symbolism of power and strength, however, wild tigers face oblivion. The March 28, 1994 issue of Time magazine was ominously entitled "Doomed. Why the Regal Tiger Is on the Brink of Extinction."

The financial history of East Asia has fascinating parallels with the history of its feline mascot. The latter part of the twentieth century was a time of explosive growth for economies in the region. The World Bank famously popularized this phenomenon with its seminal report in 1993 entitled "The East Asian Miracle."[21] But, much like the fate of the wild tiger, the region teetered on the edge of collapse by the end of the decade as the Asian Financial Crisis decimated economies and markets. A thorough analysis of this period will leave investors with a fundamental understanding of its legacies and how it shapes policies and market behavior to this day.

Finally, no view of Asia would be complete without a discussion of the 800-pound dragon in the room, China. Largely unscathed by the aforementioned financial crisis, it went from Communist afterthought to one of the world's most powerful and intimidating economic forces in mere decades. Yet, despite its economic prowess, its relevance to markets is often misunderstood. An understanding of China's recent capital markets history is equally crucial to investment success in the region.

Our story begins with a roar. In the 30 years from 1965 to 1994, the 23 economies comprising East Asia grew faster collectively than any other region in the world. Growth was strongest in Hong Kong, South Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan (known as the "Four Tigers"), and in the newly industrialized Southeast Asian nations of Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand.[22] In the 1980s, Japan's economic rise captured the attention of economists and investors. Many saw a similar phenomenon in these small neighboring nations, and stellar economic growth rates—7.5 percent annually during the 30-year period—seemed to confirm this optimism. Talk of the world's economic center of gravity shifting eastwards was commonplace.

Not surprisingly, Asian stock markets soared. While historical data are limited, in the six years ending 1993, MSCI Emerging Asia equities returned an average annualized 30 percent. (See Table 2.1.) In 1993 alone, they returned a whopping 100 percent in US dollars![23] The "Asian Miracle" was born.

Yet, miracles manifest in the eye of the beholder. A lifelong Chicago Cubs fan might see divine intervention at work should its perennially cursed baseball team finally win the World Series. But in an economic sense, miracles are bound by the natural laws governing markets. The "Asian Miracle" was no different. It may have seemed like a miracle at the time, but the region's remarkable economic record was instead rooted in a series of positive fundamental developments.

Table 2.1. MSCI Emerging Asia Stock Market Returns

Source: Thomson Datastream.[24] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

68.8% | 1999 | 69.4% | |

1990 | −17.5% | 2000 | −41.8% |

1991 | 9.9% | 2001 | 6.2% |

1992 | 18.9% | 2002 | −4.7% |

1993 | 99.8% | 2003 | 51.0% |

1994 | −14.4% | 2004 | 15.3% |

1995 | −5.7% | 2005 | 27.5% |

1996 | 2.9% | 2006 | 33.2% |

1997 | −48.2% | 2007 | 41.6% |

1998 | −11.0% | ||

In contrast with other developing nations where boom-and-bust cycles led to wild fluctuations in economic activity, Asian countries were largely successful in fostering macroeconomic stability. This stability, rooted in sound economic and public policy, was a key driver behind the boom.

A major component was fiscal prudence. The level of deficits was not markedly better in Asia than other emerging market regions, but governments were largely more responsible with public funds. Many introduced measures to rein in spending, such as Indonesia's balanced budget law or Thailand's exchange rate management framework, which resembled a gold standard. In addition, spending was easily financed by fast economic growth, high savings rates, and low debt levels. Thus, the region avoided inflationary excess money creation that destabilized other areas like Latin America.[25]

Inflation in Asia was not particularly low by developed market standards at the time—in some countries it surpassed double digits (as is often the case in developing regions). But it compared favorably to other high-growth emerging markets. For example, in the 10 years from 1984 to 1995, the average annual inflation rate in emerging Asia was 7 percent. The same measure for emerging Europe, the Middle East, & Africa (a common regional grouping) was 49 percent.[26] Even more critical was its consistency—the huge inflationary spikes of decades past disappeared. Steady and lower inflation kept real interest rates stable and the cost of capital predictable, a critical driver propelling investment and business activity.

While exchange rate policy shifted periodically throughout the boom, it too was prudently managed. Unlike Latin American countries, Asian nations rarely used currency as a tool to fight inflation (arguably because it was never necessary). Big swings in the real exchange rate were uncommon.

Last, governments were quick to respond with policy adjustments in times of stress. For example, as an oil importer, Indonesia faced rapidly worsening terms of trade caused by declining oil prices. The government responded decisively and devalued the rupiah in 1983 and 1986, cut expenditures, and rescheduled costly capital-intensive projects. The quick response reined in the country's deficit, staving off a much larger shock.[27]

High savings and investment rates were also byproducts of macroeconomic stability and rapid economic growth during Asia's economic boom. Many suggest culture plays a role in how much a society saves, noting that Asians traditionally put away more than any other group in the world. While these factors may have had some bearing on behavior in Asia, the government played a key role, too. It instituted many policies—some good, some bad—to ensure the economic bounty was saved and invested.

First, the good:

Property rights were relatively well protected. Property rights are crucial to well-functioning capital markets and economies. If property rights are not secure, there is little incentive to invest. Developing regions usually lag developed nations in this respect, and incremental improvements can make a big difference.

Sound tax policy. Low effective tax rates meant the populace kept more of their money, encouraging private savings and investment. Governments achieved this through a variety of measures. Taiwan, for example, had very low levels of effective income taxes due to extensive exemptions. Meanwhile, Hong Kong more directly maintained low marginal rates—around 15 percent for personal taxes and 17.5 percent for businesses.

Postal savings institutions. So called because they were located in government post offices, these were essentially financial institutions backed by the government. They offered small savers greater security and lower transaction costs than the private sector and were thus successful in attracting poorer and rural households. Until these systems were developed, rural citizens were often shut out of the financial system. While such policy involved the government, it proved worthwhile because it promoted saving at the rural level.

But there was also bad:

"Forced saving" programs. Many governments instituted a variety of "forced saving," like mandatory pension schemes, restrictions on consumption and limitations on borrowing for consumption (e.g., purchases on credit). For example, Malaysia and Singapore had mandatory pension plans for their citizens. While an effective policy in the short term (people usually do what you tell them when forced), it had negative implications for the long term as it restricted the free flow of capital.

Restricted capital flows. Savings and investments abroad were often disallowed. The logic here is straightforward: If investors can't send money out of the country, they'll invest domestically instead. Japan, Korea, and Taiwan all did this. But it's bad for investors because it ultimately restricts the investment universe and leads to pricing dislocations.

Artificially low interest rates. Governments intervened to hold interest rates below market levels to encourage investment. This caused distortions and imbalances as holding interest rates low for too long creates a disincentive to save, but high rates can restrict investment.

Whatever the individual merits of each policy, they generally worked as a whole to stimulate savings and investment. Consider the case of Singapore, where investment as a percentage of output rose from 11 percent to more than 40 percent between 1966 and 1990—a massive investment in physical capital.[28] Virtually every country in the region went through a similar adjustment.

Emerging market countries generally don't have a sufficient middle class to demand goods as a source of internal growth like the developed world. Governments realized manufacturing and exporting provided an alternative and in the 1960s and 1970s underwent a period of massive industrialization, adopting export-driven growth models. Today, a disproportionate amount of clothes, shoes, and home electronics—a huge portion of our consumable goods—are manufactured in Asia and shipped to households or storefronts around the world. The approach varied across countries, but each government generally pursued export-friendly policies. The ensuing export push further fueled the economic boom.

To encourage exports, many countries sought to avoid an appreciating local currency, and in some cases purposely undervalued theirs. A strong currency makes a country's exports more expensive (and its imports less costly) and thus less competitive. To see why, imagine you're a manager at Don's Dishwashers, a dishwasher manufacturer located in Taiwan. You sell most of your goods to Ken's Kitchen Wholesalers in the US. The current exchange rate between Taiwan and the US is two to one, which means your 200 Taiwanese dollar dishwasher costs Ken 100 US dollars. Now imagine that the exchange rate depreciates, and it now takes three Taiwanese dollars to buy one US dollar. What does your dishwasher cost Ken now? 33 percent less, or $66.67! That's incentive for Ken to buy more goods from Don—a happy situation for both!

But how did governments accomplish this? Most countries in the region maintained a fixed exchange rate, meaning their currency was pegged to the US dollar. When a country pegs its currency to another, the exchange rate between the two barely moves. This process doesn't happen naturally—a country maintaining a pegged currency will be forced to buy or sell its currency to keep its value close to the pegged value. For example, Hong Kong maintains a US dollar peg, currently at 7.75 Hong Kong dollars to one US dollar.[29] Imagine that the demand for Hong Kong condominiums is exceptionally strong. Real estate speculators rush to trade in their foreign currency for Hong Kong dollars to get in on the action, pushing its value up—the more something is demanded, the higher its price. But since the Hong Kong government maintains a peg, it is forced to sell Hong Kong dollars into the currency market to counteract the upward pressure from the real estate speculators.

Exchange rates were manipulated in other ways to favor exporters. Some, like South Korea, used different effective exchange rates for exports and imports through subsidies, tax breaks, and tariffs. Others, like Indonesia, simply adjusted the exchange rate through large devaluations.

Governments also practiced protectionism in the form of subsidies and tariffs. For example, they granted domestic exporters duty-free imports on the capital and intermediate goods necessary to manufacture their exports while continuing to protect domestic consumer goods from foreign competition.

Later in the economic reform process, governments turned their attention to liberalizing the financial sector, which helped the boom continue. Interest rates were deregulated, competition stimulated, and regulatory systems reformed. Many financial markets and exchanges we know today were born during this time.

If you stopped reading here, you'd leave with the impression Asia was a one-way ticket to prosperity. Near the end of the century, everything appeared to confirm this thinking. Investors were convinced the region's extraordinary economic growth record meant it was immune to traditional business cycles (i.e., "it's different this time").

But, of course, nothing is ever different this time. No investment segment stays on top forever, and the East Asian boom was no different. A crisis of unforeseen proportions ripped through the region in 1997 to 1998, leaving not just companies but entire countries on the brink of collapse. Ironically, many of the characteristics fostering the economic miracle in the first half of the decade left the region needing just that to survive.

The exact cause of the Asian Financial Crisis is open to debate (we'll discuss that in a moment), but the trigger point is widely accepted—a run on Thailand's currency, the baht. By the mid-1990s, some of the luster of the Asian economic boom began to wear off. The devaluations of the Chinese yuan and Japanese yen along with a sharp decline in semiconductor prices weighed on export revenues and overall economic activity. In Thailand, these events were accompanied by speculative pressures on the baht.[30]

Beginning in May 1997, Thailand began to spend billions of dollars of its foreign currency reserves defending its currency from speculative attacks. Then, on July 2, 1997, after months of saying it would do nothing of the sort, Thailand abandoned its efforts to maintain its peg to the US dollar. Its currency plummeted as much as 20 percent, reaching all-time lows.

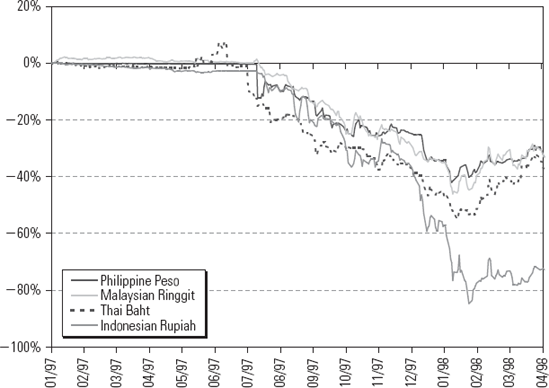

Thailand's devaluation rippled through the Asian region with alarming speed, first affecting nations deemed vulnerable to similar financial and economic problems. Within just a few days, the Malaysian central bank intervened to defend its currency, the ringgit. The Philippine peso devalued on July 11. Indonesia also floated its currency, the rupiah, on August 14. Figure 2.1 demonstrates the severity of the region's currency sell-off. By the time the crisis reached South Korea, the then 11th largest economy in the world, worries of a global financial meltdown were pervasive.

Big devaluations soon gave way to worries of financial stability, as deteriorating bank balance sheets led to widespread bankruptcies. Devaluations are a double whammy to firms—they make assets worth less and liabilities increase. In an attempt to restore order and confidence, Asian nations began calling on the help of international aid organizations. On August 5, Thailand adopted tough economic measures proposed by the IMF in return for a loan of $17 billion. Thailand's government shuttered 42 financial firms as part of the IMF's austerity measures (another 56 were closed in December). In October 1997, Indonesia received an IMF loan package of $40 billion and closed 16 insolvent banks (by the end of the crisis, it would have entered into four separate agreements with the IMF). And in December, South Korea got the biggest of them all—$57 billion.[31]

The crisis soon began to test the social and political order. For example, in early January, Indonesians fearing economic collapse began to clear store shelves of food and staple items. Prices for basic food staples leapt 80 percent a week later. By May, demonstrations protesting these steep increases denounced President Suharto's administration. When troops fired on a peaceful protest at a Jakarta university, killing six and sparking week-long riots, Suharto's 32-year reign as Indonesian president was doomed.

Next, things spilled over to rest of the world in a phenomenon called contagion. The Dow Jones Industrial Average fell 554 points on October 27, 1997, the biggest daily point loss ever to that point, as the broader turmoil weighed on confidence in the US. One of Japan's largest brokerage firms went bankrupt in early November. Others soon followed. And many other countries, such as Brazil and Russia, saw similar sell-offs. (The crisis set off a separate, concurrent crisis in Russia that will be explored in Chapter 4.)[32]

By the end of 1998, the carnage was unmistakable. MSCI Emerging Asia equities fell 48 percent in 1997, compared to a 16 percent rise in the MSCI World.[33] But even that vicious decline masks the true damage, as the index was buoyed by countries like Taiwan and India that were relatively unaffected by the crisis. Many of the countries hardest hit lost more than two-thirds of their value. Economic growth also ground to halt—a miracle no longer. Table 2.2 shows each country's stock market in 1997 and economic performance the following year.

Table 2.2. The Aftermath: Equity Markets & Economic Growth Plummet

1997 MSCI Market Return | 1998 GDP Growth | |

|---|---|---|

Source: Thomson Datastream; MSCI, Inc,[34] International Monetary Fund. Emerging Markets and Emerging Asia GDP figures represent nominal GDP-weighted real growth. | ||

China | −25.3% | 7.8% |

India | 11.3% | 6.0% |

Indonesia | −74.1% | −13.1% |

Korea | −66.7% | −6.9% |

Malaysia | −68.0% | −7.4% |

Pakistan | 28.1% | 2.6% |

Philippines | −62.6% | −0.6% |

Taiwan | −6.3% | 4.5% |

Thailand | −73.4% | −10.5% |

Emerging Markets | −11.6% | −1.1% |

Emerging Asia | −48.2% | 0.8% |

The devastation of the crisis is clear. Less so is the cause. Three major theories have emerged: a classic mania and panic, an inevitable crisis triggered by the run on the Thai baht, or austerity measures by the IMF exacerbating what would have otherwise been a bump in the road. It was probably some combination of the three, with an emphasis on many of the economic and industrial policies that led to the boom in previous decades. Each, however, leaves us with important legacies for investing in the region today.

Manias and panics are recurring phenomena in financial markets.[35] While the cause of each is distinct, they have a common theme: Enthusiasm for a market or asset rapidly loses touch with reality. Asset prices rise to extraordinary heights before confidence and greed turn to fear and despair, sending markets into a tailspin.

In 1637, tulip mania hit the Netherlands. Prices of the newly introduced flower reached more than 20 times the annual income of a skilled craftsman.[36] In 1711, the South Sea Company attracted a flood of investment after buying the rights to all trade in the South Seas for a £10 million IOU. Poor management failed to deter interest in the stock, which reached £1,000 (unadjusted for inflation) before plummeting to zero when the South Sea Bubble burst.[37] More recently, technology mania in the late 1990s spurred a proliferation of technology company IPOs, though many had operations that were not fundamentally viable. Equities of companies with no real earnings reached stratospheric heights before collapsing in 2000.

The Asian economic "miracle" showed many of the same characteristics. Stock returns, as previously mentioned, inflated fast—doubling in 1993 alone. Other asset classes (like real estate) also witnessed explosive demand growth. For example, from 1990 to 1997, nearly one million new housing units were registered in Thailand. That was more than double the previous two decades combined.[38]

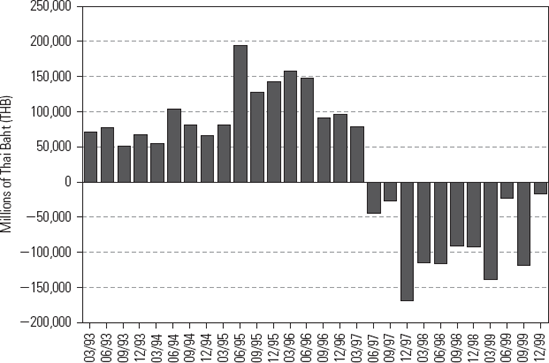

Similarities also existed on the way down. Panic set in when investors realized Asia wasn't the investing panacea they thought it was. The sharp reversal in Thailand's capital account is evidence of investors running for the exits. As shown in Figure 2.2, the country's capital account averaged around 100 billion baht through 1995 and 1996, illustrating a net inflow of foreign capital. By 1997, however, it plunged to a deficit greater than 150 billion baht. A similar fate occurred in other Asian countries.

But manias and panics are behavioral in nature and therefore difficult to prove. Asia in the late 1990s did exhibit many of the symptoms of classic manias, and the panic exodus of capital certainly exacerbated an already dire situation. But a spate of fundamental economic imbalances suggests there was much more at work.

Another school of thought argues rapid economic growth disguised fundamental weaknesses that existed for decades in the Asian financial system. This argument regards the run on the Thai baht as merely a tipping point to an inevitable crisis. There are some truths to this story, rooted in two factors.

A crucial part of Asia's economic ascendancy was access to foreign capital. As mentioned in Chapter 1, emerging markets are riskier, thus commanding higher risk premiums. In other words, investors require at least the potential for greater reward in return for taking extra risk. As such, interest rates in emerging markets tend to be higher than the developed world. A 12 percent interest rate would appear like highway robbery to the average US homebuyer, but rates that high (and even higher) are commonplace in emerging markets. Asia in the late 1990s was no exception.

High interest rates had ramifications for the region's banks. Banks are in the maturity transformation game. They accept short-term deposits—liabilities—and use that money to issue long-term loans—assets. This is the basic way any bank does business and is extremely profitable if long-term interest rates (what they receive) are notably higher than short-term interest rates (what they pay).

Under this model, Asian financial institutions willingly offered loans at the prevailing higher interest rates. But they were understandably averse to paying out high interest rate deposits to fund those loans. Thus, in order for an Indonesian bank to make a loan in its local currency, for example, it was tempted to accept low-interest funding in other currencies instead of relatively high interest rupiah deposits. This happened across much of Asia at the time.

Such a model in itself isn't necessarily a bad thing. After all, emerging economies often need foreign capital to grow. But emerging markets are characterized by immature capital markets infrastructure. In Asia's case, this meant underdeveloped bond and derivative markets, leaving banks without the necessary tools to hedge currency exposure. Although most bank lending was denominated in domestic currencies, the liability side of the balance sheet was saddled with substantial amounts of unhedged currency risk. The tendency to take on this foreign currency risk was even greater because of their US dollar pegs. In normal times, this exposure didn't pose too much of a problem. But this period was far from normal.

When Asian nations broke their US dollar pegs and devalued, their high levels of debt held in foreign currency had disastrous consequences. Why is this so? Let's say you're an Indian bank and accept a $100 investment from an American banker and the current rupee exchange rate is 30 rupees per one US dollar. As of today, you owe 300 rupees to the banker. Now, let's say the exchange rate suddenly goes to 60 rupees to one US dollar, or a 50 percent devaluation (similar to moves in many of the countries involved in the Asian Financial Crisis). How many rupees do you owe now? Twice as many—600! In a matter of months, many Asian banks saw the size of their liabilities more than double. Even the healthiest bank would be hard-pressed to survive a shock like that. But Asian banks were especially vulnerable. Bank management, regulators, international investors, and government officials all underestimated the risk of such exposure.

Another key driver behind the Asian economic boom was directed credit. At the time, government-directed lending was crucial to economic growth. Capital market infrastructure was lacking and the banking system poorly developed. Arguably, someone had to fill the void. But no government, emerging or developed market, allocates capital very well. Always and everywhere, private institutions and free markets do a better job. The unintended consequences of public involvement were evident in every country, but we'll focus on the chaebol structure in South Korea as it offers some of the most egregious examples.

Park Chung Hee, leader of the military coup that took control of South Korea in 1961, emphasized state control of the economy and the promotion of large corporations and conglomerates, or chaebol. Initially, these were firms that showed the most success in the export-driven push described earlier in this chapter. While subsequent governments tried to pry influence from the chaebols, many still exist today. For example, Samsung may be a familiar name as an electronics maker. But that's only one out of many companies in the family—Samsung Securities, Samsung Fire & Marine, Samsung Engineering & Construction, etc.

In order to control and support the chaebol system, Park allocated low-interest loans through state-controlled banks. This created an alliance between the government, large corporations, and the financial system that underpinned the economy. The government also gave these firms assurances that credit, tax exemptions, and other support would remain available. Within this vast interconnected web, corruption flourished. It was an arrangement that would make even Don Corleone proud.

With access to cheap capital implicitly backed by the government, the chaebol went on a feeding frenzy. By the early 1990s, the largest 30 chaebol accounted for 49 percent of assets and 42 percent of sales in the manufacturing sector.[39] This boom was fueled almost exclusively by debt: The debt-to-equity ratio of all Korean manufacturing firms was a whopping 3.96 in 1997. That is, for every Korean won of a firm's equity, there was nearly four won of debt behind it! To give you an idea of how extreme that is, the US manufacturing average was 1.54 at the time.[40]

Such high leverage left the financial system vulnerable to shock, and the Asian Financial Crisis was just that. Bankruptcies were rife as the financial system essentially collapsed. Daewoo Group was the most infamous default, with $80 billion in unpaid debt.[41] At the time, it was the largest bankruptcy in history—not just in emerging markets, but the world.

The chaebol and South Korea illustrate two inherent flaws with directed credit: Banks are not free to allocate capital based on economic interest and the implicit guarantee behind government-backed credit encourages risky behavior because losses are limited. Directed credit had built an economic juggernaut on a faulty foundation.

Other observers heaped blame on the IMF, arguing its actions precipitated the crisis. The IMF is tasked with the lofty aspiration of safeguarding the stability of the international monetary system, which was clearly shaken by the crisis. In a bid to restore confidence, the organization immediately offered assistance.

In 1997, the IMF arranged $35 billion in support for the three countries most affected by the crisis—Thailand, Indonesia, and South Korea. They also arranged an additional $77 billion in financing from multilateral and bilateral sources. By 1998, due to additional assistance needed by Indonesia, these figures increased another $1.3 billion and $5 billion, respectively—nearly $120 billion in total aid. The loan arrangements were to be used to meet foreign debt payments that the countries otherwise couldn't afford. It was an unprecedented intervention.[42]

In return for assistance, the IMF forced countries to adopt a series of austerity measures. This is where many believe the organization made matters worse. They imposed tough measures: monetary policy tightening, harsh fiscal austerity, and larger longer-term structural reforms. Many criticized these requirements as unnecessary or misdirected. For example, the IMF instructed the recipient nations to dramatically cut spending. But, as we saw earlier, Asian nations had huge amounts of savings, and governments were running budget surpluses. Cutting spending was arguably unnecessary (and possibly counterproductive), furthering recessionary pressures. Also, the required shuttering of banks, ostensibly done to strengthen the financial system, had the opposite effect as depositors began pulling money out of all banks, healthy or not.[43]

Interestingly, crisis-inflicted Malaysia was the only country that refused IMF assistance and advice. Despite some bumps on the road, it successfully navigated the crisis. Many take this as evidence the countries should have been left alone.

But for all the blame heaped on the IMF, it's often forgotten that the countries themselves were at fault as well. Political wavering was commonplace. Asian leaders were fiercely guarded and the loan packages unpopular. Governments took too long to draft up new economic plans and longer still to actually implement them. In South Korea, presidential candidates in the December 1997 elections loudly disavowed the program, raising questions whether agreed-upon aid would even find its way to the country.

In retrospect, the IMF perhaps didn't fully appreciate the crisis was different from past examples—the problem didn't lay with the handling of the economy by the government. Instead, it was mostly the private sector (albeit heavily aided and abetted by government policies). Fair or not, the organization received a large portion of the blame for making matters worse. To this day, it's viewed warily throughout Asia, and government policy in the aftermath has partly focused on never having to call on its help ever again. It's a bit too simplistic to say that everything would have worked out fine without the IMF, but it certainly contributed to the pain.

More than 10 years later, what relevance does the Asian Financial Crisis have for investors today? The answer is quite a lot. To be clear, none of the following provides answers on how to avoid the next crisis. Understanding the legacies of the crisis, however, gives investors important context.

The Asian Financial Crisis taught the investing world the concept of contagion. The crisis originated in a small country but soon spread globally to much larger, more developed economies. Why was it so virulent? There is no single answer. Some say Thailand's collapse served as a wake-up call to investors to re-evaluate other emerging markets. When similar problems were discovered, the crisis spread. Others believe sheer panic was the cause—investors were so alarmed by the crisis they abruptly pulled their investments out of all assets viewed as risky. Whatever it was, the Asian Financial Crisis showed us that correlations between emerging market countries are highest during crises (i.e., their markets all decline).

The Asian Financial Crisis was first and foremost a currency crisis. The dislocations in the region's currency markets exposed the underlying weakness of the financial system.

In many ways, currency crises are self-fulfilling. While some currency weakness helps export competitiveness, too much is bad—it breeds economic instability. Foreign investors run for the exits as the value of investments declines precipitously along with the currency. The currency comes under further attack from speculators looking to profit from further falls. This is a vicious cycle—a weak currency begets an even weaker currency. These cycles are prominent in emerging markets history. Really big currency moves are always an indication something is happening that's worth understanding.

Another legacy of the crisis—too much debt—is often misunderstood by investors. Repeatedly, debt is denounced as evil without distinction between good and bad debt. Debt acquired in a financially responsible manner to grow and invest is an ancient practice and a good one—it fuels economic dynamism. We don't criticize Wal-Mart for taking on debt; it wouldn't be where it is today without it. Bad debt, on the other hand, is bad: It's acquired inappropriately, put to inefficient use, prohibitively expensive, and so on. This is the stuff carried by banks during the Asian Financial Crisis and should be a warning to investors.

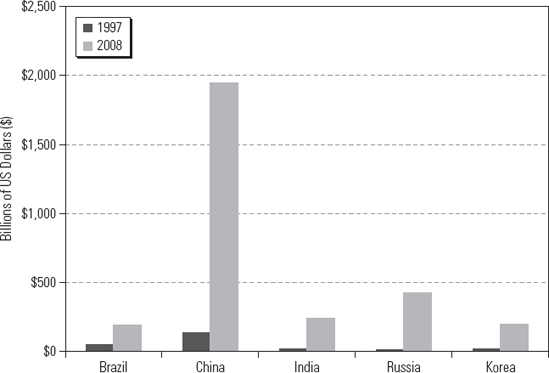

Capital flows were beneficial to economic development, but the crisis showed how vulnerable countries were to sudden reversals. Governments thus realized the need for greater currency reserves to promote stability. As Figure 2.3 shows, emerging market governments (and not just Asian) embarked on a massive accumulation of reserves over the next decade. China stands out—its reserve holdings dwarf all other countries because of its massive trade surplus. But other countries increased reserves at an even faster rate. Russia, for example, holds over 24 times more in 2008 than a decade earlier. As of this writing, a new financial crisis is unfolding, with many of the same currency pressures as the Asian Financial Crisis. This time around, many emerging markets have leaned on these reserves to maintain stability.

China's economic history is an ancient one—stories of Marco Polo and the Spice Route have captured the imagination of scholars and historians alike for centuries. Opening a newspaper or turning on the television today has the same effect, with enthusiastic stories of its economic might. Indeed, China has rapidly ascended the global economic food chain in the past several decades. But often lost amid the awe: The Chinese stock market is a relatively new creation—underdeveloped, plagued by structural inefficiencies, and subject to the whims of an often heavy-handed government. This clashes with popular perception, leaving investors with a clouded view of China's role in the global capital markets.

Modern Chinese history begins in 1949. That year, the Communist Party of China (CPC) led by Mao Zedong ended a bitter civil war lasting over two decades, establishing the People's Republic of China, as it's known today. For the next three decades, Chairman Mao led China through a series of economic reforms based on communist principles. In hindsight, these reforms impeded economic progress more than they helped, and Mao's policies had virtually nothing to do with turning China into the economic powerhouse it is today.[44] In fact, it was his death in 1976 that truly marked the birth of the modern Chinese economy.

A struggle for power followed Mao's death, and in 1978, Deng Xiaoping wrestled control from Mao's designated successor. Deng's rise to power was a critical turning point for the country. Under Mao's rule, China's economy was crippled by the collectivist principles of communism. Deng's model, aptly named gaige kaifang (literally, "reforms and openness"), offered an escape. His goals were unique—paradoxical even—to the communist way. Deng tried to reconcile capitalism's belief in free markets with Marxism-Leninism views on central planning, a model often referred to today as "market socialism."

Deng recognized the path to economic prosperity involved liberating the creative energies of the people and allowing market forces to prevail. Communist communes were disbanded. Peasants and farmers were allowed to lease the land they worked on for as long as 30 years. Families were required to pay a certain quantity of goods to the state at a fixed price for their rent, but they were openly allowed to sell anything beyond that in free markets. Deng also endorsed an "open door" policy of economic engagement with the rest of the world. He let in foreign capital, technology, and expertise.

Though the spirit of these reforms suggests eager progress toward the adoption of free market values, the Chinese system at the time was still a long way away from what we call capitalism. The state still dominated key cogs of the economy (and maintained a stranglehold on politics). But it was a system that could at least get along with the increasingly capitalistic world outside its borders.

In fact, in some ways the new Chinese model was a remarkably effective method of economic organization. By definition, democratic nations need consensus to pass laws or adopt economic reforms. China, on the other hand, could use its state-controlled machine to force through whatever it wished. Such political authoritarianism meant life could still be brutal, but the economic results were undeniable. The economy boomed under Deng, growing at an average annualized pace of 9.9 percent from 1981 to 1989.[45] China was no longer an afterthought, but a nation finally beginning to flex its economic muscles on the global stage.

It wasn't until shortly after official retirement, however, that Deng scored his coup de grace. During his now-famous "southern tour" in 1992, Deng ceremoniously traveled to southern provinces. In various speeches throughout his tour, he urged the population to "be a little bolder, go a little faster," and roused support for his visions of economic reform and openness.[46] Deng's speeches lit off a firecracker of activity—the economy expanded 14.2 percent in 1992 and 14.0 percent in 1993.

By the mid-1990s, China was an unstoppable force not even the Asian Financial Crisis could derail. Despite Deng's open-door policy, China hadn't yet intertwined itself with the rest of the world quite like other East Asian nations. It had a closed capital account (meaning no money could flow out of the country), didn't rely on foreign debt, and the state still played a dominant role in the country's financial flows. Growth slowed somewhat due to the follies of its neighbors—to a low of 7.6 percent in 1999—but it was hardly a catastrophic slowdown.[47]

Following the crisis, China resumed its torrid pace of growth. By now, it was the world's manufacturing center, offering abundant cheap labor. Trade with the rest of the world exploded. Exports rose from $52 billion in 1989 to $1.2 trillion in 2007. China's thirst for the world's goods was equally impressive, rising from around $60 billion to nearly $1 trillion over the same period.[48] To put the sheer scale of this rise in perspective, consider China's combined exports and imports were larger than Italy's entire economy in 2007.[49]

But it wasn't just trade—the scale and speed of investment were also unprecedented. According to the Economist, from 2001 to 2005, more was spent on roads, railways, and other fixed assets than was spent in the previous 50 years. Between 2006 and 2010, $200 billion is expected to be invested in railways alone, as the country ambitiously lays down 75,000 miles of track in the world's largest railway expansion since the US transcontinental line in the 1860s.[50] Gross capital formation, a broad proxy for overall investment, averaged 15 percent annual growth in the 12 years ending in 2007, from $250 billion to $1.3 trillion.[51]

Years of strong economic growth also dramatically lifted wealth, leading to a burgeoning middle class with money to spend and increasingly expensive tastes. With over a billion people, the Chinese consumer became a coveted end market.

These developments are rightly intoxicating to investors. China's economic growth story is unlike anything most of us will ever see in our lifetimes. Not surprisingly, investors hone in on these credentials as proof the country offers the opportunity of a lifetime. Unfortunately, structural impediments created by the country's political model mean its economic accomplishments don't necessarily translate to investment reality.

It's common for investors to correlate economic strength with positive markets (or a slow-growing economy to market weakness). A fast-growing economy implies healthy economic developments, and markets should reflect that by moving upward, right? Meanwhile, slowing growth raises recessionary fears, and markets should be correspondingly spooked. Makes sense! Except it's not quite right. Economic events may impact market fundamentals or sway sentiment, but they are not the primary drivers behind market performance—ultimately supply and demand for securities are. China's capital market history is a textbook example of how distortions in the supply and demand of equities can render macroeconomic analysis moot for investors.

Relative even to some of its emerging market peers, China's stock market is a recent creation. It was born December 1990 with two exchanges—the Shanghai Stock Exchange and Shenzhen Stock Exchange. (The market had been disbanded with Mao's rise to power in 1949.)

Table 2.3 shows annual stock market returns for the Shanghai Stock Exchange Composite since inception. Early trading was massively bullish. In 1991 and 1992, the first data available, the composite rose over 500 percent! Markets took a breather in 1994 and 1995, but they took off once again the following year and rose fairly consistently through 2000. It was by all accounts a rewarding time to be in Chinese stocks. An investor who bought $1,000 worth of Chinese shares in 1991 would have had nearly $16,000 10 years later.[52]

But all bull markets come to an end. In 2001, the market turned abruptly downward, entering a vicious bear market. By the close of 2005, the Shanghai Stock Exchange had lost nearly half its value. Markets rebounded dramatically in 2006, kicking off another massive bull market. In 2007, markets had yet another incredible year, returning 97 percent.

What was the Chinese economy doing all this time? Surely following the up and down fluctuations of the market, right? Hardly—it powered ahead as if nothing had changed. While equities cycled through boom and bust, the economy averaged over 10 percent growth a year.[53] But if the economy wasn't behind the market, what was?

Stocks are like anything else bought and sold in a free market—prices are determined by supply and demand. In the short term, stocks are primarily driven by demand. Why? Demand can change almost instantaneously. A single earnings release, management change, or shift in the macroeconomic climate can quickly change investment demand.

The supply of stocks, on the other hand, isn't so malleable. New stocks usually come to market via initial public offerings (IPOs) or secondary offerings—which don't happen overnight. Investment bankers and corporate executives see when a particular category is getting hot, and they join in on the fun by issuing shares too. This process takes time and, because demand is high, prices keep rising. The more prices rise, the more supply is created.

Eventually supply, or the anticipation of more of it, outpaces demand. Either there are no more buyers or prices just get too high and demand can't grow fast enough to keep up—and thus prices fall, sometimes dramatically. Look back no further than the beginning of the millennium to see this cycle at work. In the first quarter of 2000, there was an average of four public stock offerings every trading day in the US alone. Globally, there were over 13 offerings per day![54] What does this have to do with Chinese stocks?

When China's stock exchanges were introduced in the early 1990s, only a small portion of each company's outstanding shares was made tradeable, or floated, as "A-shares." The other two-thirds represented interests of the state and were non-tradeable, presumably so the government could maintain control over them.

One can easily imagine how this would distort the market's natural pricing mechanism. With only a small percentage of outstanding shares available to the public, equities soon began to trade on their scarcity value, not fundamentals. The government exacerbated the situation by declaring the non-tradeable shares would never be sold into the open market.[55] This meant market participants could effectively take supply out of the equation. With this constrained supply and strong demand, prices went higher and higher. This largely drove the big market run-up throughout the 1990s.

By the turn of the decade, however, the government began to reconsider the existing share structure. It understood such restrictions interfered with its original intention of modernizing companies through stock market listings. As such, the government began discussing possible mechanisms to float state-owned shares. In 2001, China's security regulator made an announcement the market interpreted as a sign the government would allow the full float of the shares without any compensation to exiting shareholders.

Investors hate uncertainty, and markets nosedived as the rumor spread. Chinese officials were slow to react to the problem, and fears of massive dilution from the government's supply of state-owned shares continued to weigh on equities for the next several years. It was the fear of this supply overhang that primarily drove the five-year bear market from 2001 to 2005.

By mid-2005, the Chinese government rolled out a plan to convert non-tradeable state shares into freely tradeable ones. While details varied across firms, the share-conversion program dictated that existing A-share holders be compensated for the dilution of their shares and, more importantly, that the converted state-owned shares be "locked up" for three years. This effectively meant the state-owned shares would remain untradeable for at least another three years. For all intents and purposes, the status quo was maintained.

The lifting of uncertainty had predictable results. Now assured there would be no state-owned share supply dump in the near future, investors rushed back into Chinese stocks. At one point in 2007, over a million new Chinese brokerage accounts were opened a week; and in May, trading volumes exceeded the rest of Asia combined.[56] As would be expected, bankers were itching to get to work. They got their wish in 2006 when the government reopened IPO markets (they had been temporarily banned since the start of share reform in 2005), letting loose a share-issuing frenzy. Nearly $65 billion in new shares was listed in 2007 alone, a 280 percent increase in the amount offered in 2006.[57]

So far we have only mentioned supply, but demand can also be artificially manipulated. China's capital account is closed, meaning Chinese citizens are not allowed to invest directly abroad. The government offers a few programs that allow mutual funds to invest internationally, but the quotas remain relatively small and stringent. The Chinese are mostly stuck investing in local markets. Moreover, since China's bond market is underdeveloped and shallow, investors are forced into either hard assets (such as real estate or gold), equities, or cash. It logically follows that demand for equities would be artificially high in such a scenario. We can see this at work in the pricing differences between two types of Chinese shares, but first, some definitions.

Because of its closed capital account, there are several types of Chinese shares available.

A-Shares. The primary mainland Chinese listing. A-shares are available only to domestic Chinese investors.

B-Shares. B-shares are also listed on the mainland stock exchanges, but were originally the exact opposite of A- shares—available only to foreign investors. However, in 2001 the government opened B-shares to mainland residents. The B- share market is notably smaller and less liquid than the A- share market.

H-Shares. Chinese companies listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange. Hong Kong is a special administrative region under the sovereignty of mainland China, but has a separate government and markets are unencumbered by Chinese restrictions.

S-Shares. Chinese companies listed on Singapore's exchange.

For the most part, investors follow two markets—the A-shares and the H-shares. A-shares represent the domestic Chinese stock market and are subject to the capital controls discussed previously. H-shares are owned by pretty much everyone else, including institutional and retail investors from all over the globe.

There are many companies that list on both exchanges to tap demand from domestic and foreign investors. Since these shares represent the same company, it should follow that its price movements are roughly the same too, right? Wrong. Only domestic Chinese investors can buy A-shares. But foreign investors can buy shares any where, in any country, not just H-shares. H-shares thus reflect the demand for Chinese companies by global investors as a whole, while A-shares represent the supply-constrained Chinese investor.

Hang Seng Indexes, an index provider in the region, produces the AH Premium Index, which measures the absolute price premium (or discount) of A-shares over H-shares for the same companies (see Figure 2.4). As you can see, A-shares consistently cost more, sometimes 100 percent more, than their H-share peers! This is because demand for A-shares is artificially higher from the capital controls. Were capital allowed to freely flow, these discrepancies would likely be virtually nonexistent.

The supply and demand of equities isn't the only thing the Chinese government controls. The vast role of the state in the economy also means traditional fundamental drivers are often irrelevant.

Consider an example. You may recall the impressive statistics on railway construction—75,000 miles of track is expected to be laid by 2020. It will be the largest high-speed passenger network on Earth. If you operate a railroad company, your prospects aren't likely to get much brighter than that, right?

Not when you're a Chinese railroad company—the government has its say first. China's Ministry of Railways maintains majority control over all rail tracks, setting rates for farm products and ticket prices for migrant workers at artificially low prices to appease the vast rural population. One estimate put the Ministry's net profit margin at less than 1 percent of revenues of $35 billion.[58] Maybe that doesn't sound like such a great investment after all.

These examples exist across all segments of the Chinese market, not just railroad companies. The government has its hand in virtually every aspect of the economy and market. As such, winners and losers are often determined directly by the government, not the free market. This model is another reason why general optimism over the country's prospects doesn't necessarily lead to smart investment decisions.

Even though China's stock market history is relatively short, it offers three very important lessons to investors:

Don't confuse economics with markets. While strong equity returns sometimes correlate with a rapidly growing economy, it isn't a necessary condition.

Look for structural factors affecting the market. Many times structural factors can trump fundamentals. Investors should be aware of how these factors may impact a country's equity markets, and, if they exist, look to foreign companies that may have exposure to the country's economics but not the structural impediments.

Be wary of government. There is no getting around government meddling in equity markets, and it is especially egregious in emerging markets. Where possible, choose investments where markets, not the government, are the primary price arbiter.