2

How Sponsorship Works

In 1983, barely two years out of business school, Brady Dougan accepted what many would have considered a mission impossible: relocating to Japan to take over the derivatives business in the regional office, grow its staff, and set a strategic course to build the firm’s Pacific Rim presence in that business. Having only joined the derivatives group of Bankers Trust in 1982, Dougan had little business experience and no background in the region. Nor did he speak Japanese. He was all of twenty-four years old.

Today, Dougan is CEO of the financial powerhouse, Credit Suisse. He looks back on his first breakthrough assignment with wonder, marveling at the extraordinary opportunity he was given and amazed that his boss placed such trust and faith in him to deliver. “I did have a strong feel for my role and my duties,” he says, “and I enjoyed the challenge of doing new things. But to ask me to take charge in Japan and grow the derivatives business for the entire Pacific Rim on my own? I was a very young manager to be doing that.”

Dougan credits his ascent to his boss, to whom he reported for nearly twenty years, not because he made it easy for Dougan, but because he made it hard. “I became the person he gave the toughest assignments to, the things that needed fixing,” Dougan observes. “He piled on the responsibilities. But because he believed in me—because he was clearly betting on me and giving me a leg up—I felt I owed him a lot and should do whatever he asked and come through with whatever he needed. That Japan posting proved to be an incredible opportunity. This sponsor of mine not only believed I was going to be successful, he then did everything he could to help me succeed.” For example, Dougan’s boss lent unvarnished feedback and wise counsel as needed and helped Dougan figure out how to meet targets and fit his operation into the larger context of the business. When Dougan stumbled, his boss came to his defense. “He’d say to senior management, ‘Okay, this didn’t go perfectly, but Brady’s overall record is very strong,’” Dougan explains. “He was always ready to run interference, manage the internal politics for me. That gave me the breathing room to take risks. And in this industry, you have to take a risk. Because only by doing so do others learn to believe in your ultimate potential.”

What a Sponsor Does

Dougan’s extraordinary career ascent attests to the power of sponsorship. Indeed, he is so sure of its value that he spearheaded a successful initiative at Credit Suisse that turbocharges the careers of high-potential women. As Dougan knows full well, sponsorship can help catapult a top performer into senior management, as well as expand the reach and impact of senior leadership. It’s the secret sauce, the missing link, the invisible dynamic that accounts for who is, and who isn’t, in power, whether that person is steering a Fortune 500 company or an Internet start-up, whether that person founds a nonprofit or chairs an academic committee. Everyone who has realized an amazing vision or exerts remarkable influence can and will point to a series of sponsors, powerful individuals who helped pull them up or fund their ventures or clear a path forward. There are no exceptions.

Sponsors do three things that mentors do not. Dougan’s sponsor, for instance, went out on a limb for his protégé, installing him at the helm of his pet project. Having plunged his protégé into uncharted waters, he provided just enough support to keep Dougan afloat, both in Japan and within the firm, talking up his talent whenever others were eager to disparage it. Most importantly, he provided him air cover, acting as a shield so that Dougan could take the risks the assignment demanded. Having chosen to invest in this particular young man, this sponsor understood he needed to do everything within his power to ensure that Dougan, and the Pacific Rim project, proved to be a resounding success.

CTI research, begun in 2010, affirms the centrality of these three functions. In addition, we also learned that a sponsor does at least two of the following: he or she will expand your perception of what you can do; connect you to other senior leaders; boost your visibility in the company; provide you with stretch opportunities; advise you on your presentation of self; connect you to clients or customers; and give you honest, critical feedback on where you need to improve your game. (See table 2-1 for a summary of a sponsor’s roles and responsibilities.)

TABLE 2-1

What is a sponsor?

Delivers high-octane advocacy

| A sponsor is a senior leader who, at a minimum: | And comes through on at least two of the following fronts: |

|

|

If you’re not in a corporate setting, it may help to think of a sponsor as a talent scout. He’ll get you in front of directors to audition for a key role. He’ll also nudge the director to choose you. But his investment in you doesn’t stop there. He’ll coach you on your performance so that you prove to others what an excellent choice he made. He’ll focus a spotlight on you so that other directors take note of your abilities, and he’ll make introductions afterward so that you can follow up with them to bring your talent to a wider audience. Should you stumble, or should any of those other directors turn hostile, your sponsor will come to your aid, because now that your brands are linked, it’s in his best interests to ensure you succeed.

Of course, sponsors also provide advice, which is why they’re confused with mentors. From CTI’s survey research it’s clear that protégés expect advice from their sponsors. Fully 74 percent of respondents told us they looked to a sponsor to provide unvarnished feedback. But it’s important to distinguish the critical feedback that sponsors deliver from the kindly advice mentors might dispense when asked. When a sponsor discusses your strengths and weaknesses, it’s with an eye to steering you along a certain trajectory, one that will provide strategic gain for both of you. To that end, sponsors will not hesitate to point out painful shortcomings—skill gaps, communication failures, appearance blunders. They’ll also tell you where and how to acquire critical line experience, build key networks, and project executive presence, which comprises looking and acting the part of a leader in terms of appearance, presentation skills, and gravitas (more on this in chapter 12). This kind of strategic feedback can be awfully hard to hear. Yet because of sponsors who articulate the unspoken and point out the unremarked, women and people of color get to crack the code of an organization, overcoming hidden biases to lever themselves into contention for the top slots.

One African American banking executive told me how he’s come to feel a “blood tie” with his sponsor, precisely because she’s asked him to take some difficult, even painful steps to improve himself. “A sponsor will smack you harder to shape up,” he observed, “but will protect you as you move to the next level. She’ll tell you the sort of things you’d never know were said about you in a meeting and would otherwise never know to correct. And if she’s really got your back, she’ll tell you how to correct them.”

A sponsor’s protection goes beyond delivering tough love, our interviewees affirmed. One tax attorney described how he supported his protégé all the way to partnership, having hired her in the first place. He was confident of her ability to deliver and when long-term clients demurred at liaising primarily with a junior person, this attorney vouched for her expertise. When she became the target of unfair criticism by another partner, he intervened, extorting from that partner an apology and a promise to look at the evidence and be less judgmental. In subtle and overt ways, he ensured that she was able to thrive, which indeed she did, making partner in four years.

Unlike mentors, that is, sponsors will go the extra mile, taking you aside to tell you what you absolutely need to know, taking detractors aside so they don’t impede your progress, and clearing a path forward should you encounter obstacles. Sponsors make it their business to see you succeed because you carry their brand. You’re an extension of them, a carrier of their torch, the putative implementer of their vision. It behooves them to do everything in their power, once they believe in you and they’ve chosen you, to keep you on track. Only by seeing you to the finish line can they protect their own reputation.

Kerrie Peraino, now a senior vice president at American Express heading up international human resources and global employee relations, describes how her supervisor kept her on track for management at a juncture in her career when other women in her position might have been derailed for good. Some years earlier, just after she’d given birth to her second child, Peraino asked for a three-day-a-week schedule. She was a mid-level manager and felt confident she could perform her duties in a compressed workweek, but also recognized her superiors might not see it that way. “That’s when my sponsor went to bat for me,” Peraino relates. “She knew I was fully committed, not just to my team but to the firm, and she was determined to give me whatever support or air cover I needed to keep me on track.” Peraino’s request was granted and, after three years of working part-time, she was made a vice president—a testament not only to her hard work, but also to her sponsor’s committed support and advocacy. “I look back on that phase and think how my career might have played out differently were it not for her sponsorship,” Peraino muses. “I really don’t think I’d be where I am today. I might even have left the firm. Since she placed such trust in me and went out on a limb to offer a flexible work arrangement, I was determined to be a credit to her.”

During economic downturns or industry upheavals, a sponsor can be the voice in the room that ensures you keep your job. One executive I interviewed recalled a watershed moment when her sponsor flew in to London from New York to secure her a promotion she was in danger of losing to an outsider. “Marcia marched into the chairman’s office, put her badge on the table, and said that it was completely transparent what was happening and that if I didn’t get the job, we were both leaving,” she related. “Her strong-arm tactics worked, because she was tremendously valued. They decided to go ahead and appoint me.”

When your job is on the line, your sponsor can at least ensure you don’t damage your career over the long term. Darren, a director in the advisory practice of a large accounting firm, told me how he went to bat for a protégé about to be fired because he’d been part of a group that had engaged in less-than-ethical practices in the run-up to the global financial crisis. “I did not just buckle over and go with the groupthink about the treatment this guy should get,” Darren recalls. “I felt he was being unfairly tarnished, and I let my feelings be known to my peers as well as the people he reported to.” When that didn’t work—he was outnumbered and outvoted—he counseled his protégé to “take control of his destiny” and quit, so that he could leverage his track record without the stain of a job termination. Darren made introductions and spoke favorably on his protégé’s behalf, an effort that culminated in a job offer at another “Big Four” accounting firm where the executive could distance himself from the events of 2008. “I may not have saved his job, but I believe I did save his career,” says Darren.

What a Protégé Does

Maria, a managing director at a financial services firm with nine hundred technology professionals reporting to her, has always been a hard worker and a strong performer. Even employees whose jobs she’s eliminated speak highly of her. She’s come a long way from Dominica, where she was born, and Washington Heights, where she grew up. Still, as a dark-complexioned Latina leading overwhelmingly white male teams, she recognizes that being a subject-matter expert and a star producer don’t, in and of themselves, account for her leadership position. “I’ve always had the backing of my superiors,” she says, “because I’ve always made sure they succeeded at whatever they were doing.”

Her first sponsor was a colleague who became her boss. He’d signed up to lead an integration project—for the chief investment officer, and she signed up to help him. It proved to be a highly stressful, cross-functional project that eliminated a number of jobs and tested the skills of her sponsor as well as her own. Maria didn’t let him down, bringing the project to a successful close in ten months. But what endeared her to the CIO, in addition to her remarkable client-service skills, was her unflagging commitment to him. “I was his right-hand person,” she says. “I made sure that he was not surprised by anything. The thing about tech, systems are always breaking down and I was there for him. When things were going poorly I was the person saying, ‘Have you thought about this?’”

At one point, the company experienced a major data-center failure the day before Maria was to fly to California to receive a prestigious award from a Hispanic science and technology group. “It was a great honor. I was all packed and ready to go,” she recalls. But an hour before departure, she got a call from her sponsor. There was a crisis at work. So she canceled her plans and stayed to help. Afterward he told her, “I will always remember this. Thank you for always being there for me.”

And remember he did. When Maria was struggling to pull out of a career stall, he worked with her to devise a way forward, ultimately helping her land a coveted managing director position. His intervention marked a real turning point. “If you have a history of delivering, being there, being committed, and making sure your boss is successful, he or she will be there to pick you up,” says Maria. “No one’s going to do that for someone who has let them down.”

What protégés do, in a word, is deliver. As Maria intuited early in her career, they come through with both stellar performance and die-hard loyalty. They also deliver a distinct personal brand or unique skill set, a critical finding of the research. Star performers are very likely to attract sponsors, and loyal performers are very likely to keep them. But if they fail to distinguish themselves, these loyal performers run the risk of becoming permanent seconds, lieutenants who never make captain. To position themselves for the top job, protégés must therefore contribute something the leader prizes but may intrinsically lack: gender smarts or cultural fluency on a team that lacks diversity; quantitative skills or technical savvy on a team that is deficient in hard expertise; people skills on a team that’s bristling with eggheads and nerds. You could provide unique insight into a target market. You could have access to a sought-after circle of investors or stakeholders. Whatever you bring, it must burnish the sponsor’s personal brand across the organization even as it distinguishes you from the crowd, delivering you your dream job and not one as second-in-command.

Maria, for example, distinguished herself on the integration project by using her built-in proclivity (born of her culture and her heritage) to treat everyone on the team as if they were family. “I’m Latin and I’m very family-oriented,” she explains. “When I’m in charge, I want to know, ‘How’s your baby doing? Are you getting enough sleep?’ That’s one of the things people love about being in my group. I make sure it’s warm, supportive, and open.” It’s one of the things about her that secured the support of her first sponsor (“He told me never to change, no matter how rigid the manager I reported to”) and intrigues her current sponsor. “You’re very effective,” he told her. “You have some people skills that I need to lean on and learn from.”

This isn’t to diminish the performance piece of this equation. Delivering a superior product on time, winning a key piece of business, innovating a solution, and otherwise driving results with bottom-line impact are what will attract the attention of a sponsor in the first place. A third of US managers and nearly half of UK managers want to sponsor a “producer,” a go-getter who hits deadlines. “I don’t think for a second that my sponsor would promote me if I didn’t deliver superior results,” the head of audit at Lloyds observes. “I don’t feel that I can rest on my laurels just because I have her sponsorship.” A partner in Ernst & Young’s London advisory group stressed, in an interview, his key considerations when deciding whom to back: “It’s simple,” he said. “Hard work and drive. Are they the kind of person who has a work ethic similar to mine?” he asks himself and, “Will they go the extra mile?”

Debbie Storey, chief of diversity at AT&T, agrees. “It’s all about understanding the company’s goals and direction, then making things happen. It’s about continuously innovating and leading change,” she says. “They have to demonstrate by how they lead that they can consistently drive teams to achieve results.”

While performance and value added will make you indispensable to your sponsors, it is loyalty that will bind them to you and make them care about your success. Thirty-seven percent of male managers (and 36 percent of female managers) say that being a loyal protégé matters, more than being collaborative or visionary or even highly productive. If delivering a standout performance is what wins you the attention of the powerful, demonstrating loyalty is what guarantees a powerful leader will commit to sponsoring you over the long haul. (See table 2-2 for our definition of a protégé.)

TABLE 2-2

What is a protégé?

Delivers high-octane support

| A protégé is a high-potential employee who, at a minimum: | And comes through on at least two of the following fronts: |

|

|

As many of the executives in our survey pointed out, loyalty means looking out for your sponsor as protectively as your sponsor looks out for you. “Protégés can provide insights about what’s happening lower down in the organization, because when you’re at a senior level, you’re less likely to get those honest messages about what people think of you and your strategy,” says Lloyds’ head of audit, who acts as her sponsor’s eyes and ears and exhorts her protégés to do the same for her. Ed Gadsden, former chief diversity officer at Pfizer, remembers asking his sponsor, the legal scholar and federal judge Leon Higginbotham, why he took such an interest in him, aside from the fact that they were both African American. “You’re nothing like me, Ed,” Higginbotham told him. “The people you’re around, the things you see, what you’re hearing—you provide a perspective I wouldn’t otherwise have.” Now, as a sponsor himself, Gadsden has come to appreciate the perspective his own protégés provide: “They make sure I’m never blindsided,” he says.1

Just as your sponsor is someone who supports you when you’re not in the room, so too must you protect him or her from employee gossip, from harsh outsider opinion, even from collegial criticism. “Who do you want in your bunker?” an African American executive at Johnson & Johnson asked me in an interview, “A loyal comrade-in-arms who, if you turn your back, guns for you, not at you.”

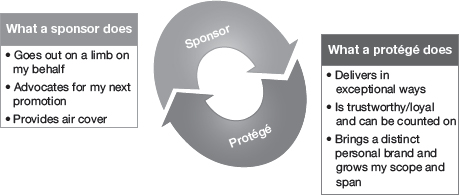

The Two-Way Street

What should be clear, at this point, is how extraordinarily reciprocal sponsorship is. Protégés attract sponsors by delivering in exceptional ways and secure sponsorship by remaining utterly devoted, even as they distinguish themselves as stars in their own right. In return, sponsors invest in their protégés, not because they’re impelled to pay it forward but because they recognize the incredible benefit to their own careers of building a loyal cadre of outstanding performers who can extend their reach, build their legacy, and burnish their reputation. Over time, both parties win. Indeed, the win-win aspect of sponsorship is what accounts for its extraordinary leverage and durability. (See figure 2-1.)

FIGURE 2-1

The two-way street

Contrast this to the decidedly one-way street of mentorship. Mentors give: they devote time, impart wisdom, and act as a sounding board (or a shoulder to cry on). But mentees merely recieve: they have no particular responsibilities other than to show up and listen. Mentors take an interest in the mentee’s career, but not a stake in it, as they’re not going to be held accountable for outcomes. Mentorship is at heart an expenditure rather than an investment, a gift rather than an alliance. It’s doomed to peter out: the mentee outgrows the mentor’s range of experience, the mentor moves on to needier novitiates.

What this means is that the nature of your support relationships is up to you. You’ll get back what you put in. If you’re a high-potential or strong performer, you’ll attract the interest of your superiors, but whether that interest translates into mentorship or sponsorship is a function of your investment. You might be tapped for development, but you’re not going to be given a ride on the coattails of anyone who doesn’t see you pulling your weight (and then some). Mentors may pick you, but you pick your sponsors by committing yourself to their best interests.

Because make no mistake: Sponsors, unlike mentors, really need you. They need your support and skills. They need you to build their bench strength and complement their expertise. They need you to help them realize their vision and secure their legacy. You advance their careers, surprising as that might seem. There’s a protégé effect akin to the sponsor effect in terms of career traction for leaders. White male leaders with a posse of protégés are 11 percent more satisfied with their own rate of advancement than leaders who haven’t invested in up-and-comers. Leaders of color who’ve developed young talent are overall 24 percent more satisfied with their career progress than those who haven’t built that base of support.

THE TWO-WAY STREET IN ACTION: ROSALIND HUDNELL AND JANE SHAW

The moment she joined the guests gathered for Intel Chairwoman Jane Shaw’s retirement dinner, Rosalind Hudnell knew she had arrived.

Virtually all of them were board members. She was one of only three guests who weren’t part of that inner circle. Yet with every executive she met, Hudnell felt tacit acknowledgment that she belonged. Clearly, Shaw’s inclusion of her implied that. But it was what Shaw’s invitation acknowledged: not just her seventeen years of service to the company as a diversity officer, but the respect she had acquired for her contribution to Shaw’s personal legacy, which was to advance women onto corporate boards worldwide.

Their relationship had begun when Shaw, poised to make a speech on the role of quotas in boosting women’s board participation, sought out Hudnell for advice: Given her experience as a diversity chief, what did she believe her [Shaw’s] message should be? “We worked really well together and I was honored to be asked to help her find her voice on this critical issue,” Hudnell recalls. From then on, Hudnell acted as a vital sounding board for her sponsor, helping her vet high-visibility projects. “Jane relied on me because she trusted I knew the subject matter and what she could achieve,” Hudnell observes.

More critically, Hudnell began to connect Shaw with people who could provide the forums she sought. “One of the things Jane absolutely loved was the depth of my network, the genuine relationships I’d cultivated with people,” she observed. “Every place I brought her to, she’d walk away thinking, ‘Wow, that wouldn’t have happened without Roz.’ I mean, here was this incredibly influential woman, a leader of companies, who was relatively unknown on the outside. I was proud to help change that.”

What surprised Hudnell about the invitation to Shaw’s board retirement dinner was that she never thought of Shaw as her sponsor. In hindsight, she now realizes it was a tremendous moment of sponsorship. “I want you to know Roz Hudnell,” Shaw said, introducing her last among her guests that evening, “because the work she and I have done around women and diversity is the work I’m most proud of.” Shaw went on to talk about what she had witnessed with the high esteem others accorded her everywhere she traveled. “I want you to continue to give Roz your full support,” Shaw concluded, “because the work she is doing is vital to Intel’s success.”

That was in May 2012. In early 2013, when Roz and I spoke, she had just been promoted to vice president one of only 140 such officers worldwide in a company of nearly 100,000.

Of course, Roz hastens to point out, Jane wasn’t the only one who stepped in to help her realize her leadership potential at Intel. Carlene Ellis, the firm’s first female executive, had played a seminal role when Roz first arrived, making sure she won important audiences for her viewpoint. And Richard Taylor, senior vice president of human resources, had provided her with key opportunities to take on visible assignments, including putting her in charge of CEO Paul Otellini’s involvement with President Obama’s Council on Jobs & Competitiveness and championing her VP nomination. And finally, Otellini himself had been the executive champion for diversity. “He supported my ideas, backed me up with the senior leadership team, and ultimately was the one who appointed me vice president,” Roz told me.

But it was through Jane that Roz saw her career culminate in an acceptance beyond what dogged effort and sterling credentials could ever alone have earned her. “Being invited to that event, being included in something that intimate, and feeling so at ease in a room of such power—it was the moment you always dream of when you know you’ve finally arrived,” Roz relates, “where you don’t have to prove you belong anymore.” That’s what Jane’s advocacy has done for her, she says: “She provided me with such validation—and by doing it in front of her peers it was a moment for me that was so personally powerful.”

She reflected a moment and then added, “Now is my opportunity to stay committed to make sure that I can be in a position to do that for another deserving person in the future.”

Just how important protégés are to their sponsors was made clear in a conversation I had with a Fortune 100 CEO. He told me that when he does that final interview with an executive at his company who is being considered for a promotion to the C-suite, he asks the all-important question: “How many people do you have in your pocket?” What he means by this, he explained, is “How many talented young people have you sponsored over the years—people who now hold key positions in this company—so that if I asked you to do something impossible next week that involved liaising across seven geographies and five functions, you could pull it off? How many leaders out there ‘owe you one,’ think you’re wonderful, and would give huge priority to your project?” Fundamentally, he told me, “I’m not interested in anyone who doesn’t have deep pockets.”

So have that bench strength and you will go far, as far as you make clear you want to go (you need a destination in mind, as discussed in part II). Don’t wait to be tapped for special projects or asked to assume a leadership role. Act like a leader, and leaders will take you under their wings. Show vision, and visionaries will invite you to do more of it. The power to work the levers rests squarely in your hands. As with Dorothy and her ruby slippers, unleashing the magic depends on first realizing that you already have what you need to get back to Kansas … or start your own company … or break through to the next big job … or fulfill your vision for social justice. With that realization, it’s then only a matter of making the journey. I’m going to help you every step of the way. Turn to the map in part II, and let’s get started.