7

Gender and Computing in the Push-Button Library

Historians of computing enjoy great freedom of choice in the sites they investigate, since digital devices from mainframes to microcontrollers over the last half-century have entered nearly every domain of human economic and cultural production, from the factory floor to the artist’s studio. One recent history of computing took three volumes to track the introduction of computer technology to U.S. manufacturing, transportation, retail, financial, telecommunications, media, entertainment, and public sector industries. But even this encyclopedic work of over 1500 pages devoted only 10 of those pages to the history of computing in U.S. libraries [1]. Such a proportion might be reasonable if one is attempting to investigate the economic impact or business management of computerization. But in order to begin to understand the recent history of women’s engagement with computing—part of the larger project of analyzing technological change together with the changing social meanings of both femininity and masculinity, which we might refer to as “gender”—we must explore a whole range of sites where women actively encountered, employed, and challenged computer technology [2]. Since librarianship was numerically dominated by women all through the development of the general-purpose programmable computer, looking for connections between women and computing in the library seems like a good place to start.

But investigating “the library” is no simple task. Historians of librarianship might focus on large research and academic libraries, on urban and suburban public libraries, on primary and secondary school libraries, or on a myriad of corporate and government libraries and archives [3]. No matter what the size or audience, all libraries are technological spaces, suffused with individual artifacts for information storage and access (from printed books and periodicals to magnetic audiovisual and digital media) and also networked systems for information organization and retrieval (from the drawer-filed catalog cards of a century ago to the microfilm and digital catalogs of today). In a very real sense, the library, at all of its various scales and sites, acts as an internetworked information technology made up of both human and material components [4].

The early 1960s represented a turning point for this technology in the United States, when decades-old dreams of “library automation” based on various combinations of punched-card sorting equipment and microphotography storage techniques shifted both rapidly and publicly to dreams of “library computerization” based on electronic catalog records and networked communication systems (Fig. 7.1). For example, at the 1962 World’s Fair in Seattle, the American Library Association (ALA) secured a spot at a global exposition for the first time. Its fairground library space was literally split into past and future—while one side of the exhibit made room for traditional books and the (largely female) librarians who organized them, the other side showcased a Univac computer and its (also largely female) data-entry technicians. This space-age, computer-based “LIBRARY 21,” reprised two years later at the 1964 World’s Fair in New York as “Library/USA,” was meant to send a signal not only to the fair-going public, but to legions of library workers across the nation as well: the library of the future was the “push-button” library of the computer [5].

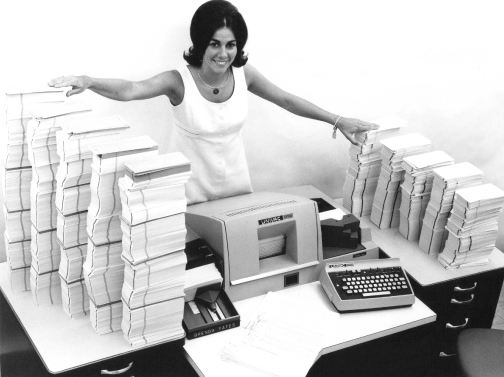

Figure 7.1. The “push-button library” promised relief from mountains of punch cards. Punch card keypunching and verifying was “hardly outmoded” in 1971, Sperry-Rand insisted, since its new equipment could verify the stack of 20,000 cards (left) in “an eight hour day” compared to earlier throughput on right.

(Courtesy of Charles Babbage Institute.)

This library of the future, though, was still very much trapped in the gender assumptions of the present. Shortly after these computer library exhibitions, the well-known library historian Jesse Shera, Dean of the School of Library Science at Case Western Reserve University, prepared “a kind of Intelligent Woman’s Guide to Automation in the Library” for the May 1964 Wilson Library Bulletin. He aimed “to set forth in as uncomplicated a fashion as possible the contributions that automation can make to the services the library could and should be offering” [6]. His own contribution to this issue characterized librarian resistance to automation as rooted in “fear” and “anxiety,” arguing that “being traditionally humanistic, librarians doubt their capacity even to utilize anything that is scientifically derived” [7]. Indeed, addressing such “doubt” was a main reason the ALA had flown in dozens of librarians from across the United States to work at the World’s Fair exhibits, benefiting from their free labor but also training them in a crash course on library automation. Such “fear” and “anxiety” did not affect the special issue’s authors, however, whom Shera described as “librarians rather than engineers or experts in computing machinery” [6, p. 742]. But these librarians (including Shera himself) were of a very special sort: all had technological knowledge or experience, all held positions of power, leadership, or consultancy in major academic or corporate libraries (as opposed to public or school libraries), and all, not coincidentally, were men.

The fact that a professional publication touting the benefits of computerization might be authored entirely by men and described in highly gendered language in the early 1960s is not surprising, given the long history of discrimination against (and discouragement of) women in U.S. government, education, and industry [8]. It had only been a year, after all, since the Equal Pay Act of 1963 first dealt with questions of sex-based wage discrimination [9]. What was surprising, however, was the fact that librarianship was (and still is) disproportionately staffed by women. Ever since the late 19th century, when Melvil Dewey (originator of the eponymous Dewey decimal subject classification system) began systematically and publicly recruiting women into librarianship—based on then-current stereotypes of women’s supposed greater attention to detail and nurturing moral role, as well as the fact that women could be paid less than men—librarianship in the United States has been demographically dominated by women [10, p. xiv].

But while librarianship was agreed to be an “intelligent woman’s” profession in a numerical sense, it was also a gendered profession in an analytical sense, in three ways. Across the main divisions of academic, public, school, and corporate libraries, a wage division of labor persisted: women working at the same jobs or performing the same tasks as men received lower remuneration regardless of age, education, or experience. Similarly, in a vertical division of labor, men held disproportionately more positions of power—directorships, management positions, or library school professorships—than women. And in a horizontal division of labor, men and women tended to be segregated into different kinds of tasks, with women more likely to perform both the most meticulous of back-office “technical services” work (cataloging and circulation) and the most nurturing of front-desk “public services” work (running children’s storytime and literacy groups). Through the 1960s and 1970s, “survey after survey reported lower median salaries for women, fewer professional perquisites, and a clouded view of the career ladder, which disclosed men at the top and a preponderance of women at the bottom of the library hierarchy” [11].

Across the profession as a whole, the very institution of the library had long been represented in the public eye as a proper domain for women workers (and women patrons). Popular culture demonstrated a broad range of such gender stereotypes—from the strict yet meek “Marian the librarian” who guarded the moral fiber of River City’s youth in The Music Man (1962, played by Shirley Jones) to the self-assured and streetwise corporate librarian “Bunny” who stood up to the installation of a mainframe computer in Desk Set (1957, played by Katharine Hepburn)—but in nearly all cases an essentialist opposition between the (feminine) traditions of the library and the (masculine) notion of technological progress was assumed [12]. Within the professional library press, advertisements at the dawn of library computerization for paper, photographic, or electromagnetic information technologies often included illustrations of female librarians using these products at the front desk to speed up routine information processing for male patrons, rather than using such tools for information-seeking themselves. During this period of computerization, even some in the library profession itself (often but not always men) advocated the view that librarianship should “guard well its feminine qualities” as supposedly embodied by its women workers, because “until libraries consist of a computer wall which the user plugs into at home, the librarian must continue to deal with people” [13].

At the very same time that librarianship was facing a new computerized future, it was also beginning to grapple with its own gender dynamics and disparities. In 1963, Betty Friedan had published The Feminine Mystique; 3 years later, the National Organization for Women was established. By 1969, the computerization dreams of the early 1960s World’s Fairs were beginning to make their way into U.S. research libraries through the Library of Congress’s new “MAchine Readable Cataloging” (MARC) standardization project (headed by female librarian Henriette Avram) [14]. At the same time, University of Illinois library science professor Anita Schiller had begun to both quantify and popularize the extent of salary and status discrimination within librarianship. Schiller reported that the median and mean salaries of men were, respectively, $8990 and $9598 compared to $7455 and $7746 for women [15]. A year later, at the ALA annual meeting in Detroit, librarians Pat Schuman and Ellen Gay Detlefsen of the ALA Social Responsibility Round Table—sporting wry buttons combining the women’s liberation symbol and the words “American Ladies Association”—convinced 500 of their fellow members to support a new Task Force on the Status of Women to address such disparity and discrimination [16,17, p. i]. As both library computerization and the “second wave feminism” of the women’s movement gained momentum through the 1970s, the field of librarianship seemed poised for an intertwined technological and social revolution.

Yet the historical record concerning sex discrimination and computer innovation in libraries through the 1970s and 1980s tells not one integrated story, but two separate ones. Library activists, educators, and historians published a wide range of materials on the gender question through this period, from scholarly theses to underground newsletters, special issues of professional journals and special sessions of annual conferences. These writers tracked the (modest) gains in wage and status disparities, revealed the presence of gender-stereotyped language in the library catalog itself, and advocated for the Equal Rights Amendment. Similarly, in the more technical literature, experts and novices alike discussed and debated the merits of computerization, especially in new forums like the Journal of Library Automation (founded in 1968). The late-1960s MARC project to create a standard format for electronic catalog records quickly led to efforts to produce those catalog records through networked cooperation online. The most successful of these efforts was the 1970s Ohio College Library Center (OCLC) project to connect participating library workers’ cataloging computers together over space and time [18]. A dramatic increase in the number and quality of electronic catalog records led directly to a series of both nonprofit and for-profit Online Public Access Catalog (OPAC) projects in the 1980s, to make those networked electronic catalogs directly available to patrons. Press releases announcing the “closing of the card catalog” were commonplace through the 1980s, serving as indicators that one’s public or university library was poised to enter the electronic future. Thus, from the late 1960s to the mid-1980s, both the back-office division of labor in cataloging and the front-desk face that the library presented to the public changed dramatically. But throughout this fervent period of professional activism, neither the feminist writers nor the technical writers connected issues of sex and gender in the library occupation to issues of technology in the library infrastructure.

This chapter considers the question of women’s participation in computing through the historical case study of library computerization. But this is a different sort of history than is usually told of women and information technology in the workplace [19]. It is neither a story of librarians programming computers in an engineering sense, nor a story of librarians using computers in a clerical sense (though both did happen). Instead, it is a story of librarians organizing for increased status and wages in a highly technological environment, but using arguments that largely ignored the technological changes taking place in that environment, only coming to a sense of their role within the digital management of library resources years after a computerized division of labor was introduced.

The first part of the chapter briefly describes the most active period of library feminism in the 1970s and 1980s, to demonstrate that female librarians were indeed aware that the most blatant vertical discrimination took place in those libraries most likely to be investing in computer technology, even though these activists rarely connected arguments dealing with gender to those dealing with technology. The second part considers a set of claims that grew through the 1980s into the 1990s about the way that one of the most controversial aspects of the push-button library, the computer-aided production and reproduction of the library catalog, started to be seen in terms of gendered technological change. Finally, I offer some suggestions for understanding gender, computing, and labor within fields such as librarianship, which are intended at their core to produce, organize, and distribute both information itself and the “meta” information—or metadata—that is essential for others to find, use, and value such information. Too often the history of computing focuses only on hardware innovations or software applications. The case of library computing reminds us that computer hardware and software both manipulate computer data, and that the production of this data—and the metadata that defines and organizes it—might reveal a different kind of computer history than we are used to telling.

GENDER AND STATUS DIVISIONS WITHIN LIBRARIANSHIP, 1950–1980

To understand the “push-button” library of the 1960s as a gendered vision of the future, we must first describe the gendered division of labor within librarianship at the time. The crucial point is that in the very libraries most likely to have both the financial resources and the scientific user base to motivate experimentation with computerization—that is, large academic and corporate libraries—most of the directors and chief librarians were men. One 1950 study revealed that 84% of the directors of the largest academic libraries in the United States were men, finding “not a single woman is in charge of a library in a school with more than 10,000 students” [20]. Similarly, in the massive midcentury Public Library Inquiry, where librarians turned to social scientists to assess the state of the library as a crucial “public information agency,” library science professor Alice Bryan found that although 92% of all librarians surveyed were women, “men held higher positions, were more likely to be married, did less domestic work [in the home], brought home higher salaries, and were more satisfied than women” [10, p. xviii]. In all of the sampled libraries serving populations of 250,000 or more, “all the top administrators [were] men” [21].

By 1962, participants at a special University of Chicago conference on libraries and women concluded that “women depress the status” of librarianship, recommending the recruitment of even more men to positions of power and authority in libraries [22]. In 1971, an assistant librarian from Princeton University, Helen Tuttle, pointed out that the main academic and corporate library professional association, the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL), was clearly a male-dominated group: “Since the ALA reorganization in 1957, ACRL has had five different executive secretaries. All have been men. Its journal, College and Research Libraries, has never had a female editor. In fact, of the present nine editors and editorial board members who guide the destinies of that periodical, nine are males” [23]. The early 1970s saw the first published “sex and salary surveys” in the Library Journal, demonstrating this disparity in stark economic terms: libraries directed by men paid higher starting salaries and had greater per capita support. And the median salary for male library directors was 30% higher than that of female library directors [24].

Even the structure of library education and research publication, which might have been mustered to produce more female directors, was suspect. In 1974 Anita Schiller revealed that the proportion of accredited library schools directed by men had increased from 50% in 1950 to 81% in 1970. Library journals showed the same pattern: roughly half had been edited by women in 1950, but only one-third were by 1971. One explanation? The many new library journals, edited by men, which were wholly tied to computer technology—for example, the Journal of Library Automation and Library Technology Reports [25]. Contemporary librarians expressed dismay that the main foundation-based funding organization for library technology projects, the Council on Library Resources, gave relatively few grants to women [17, p. 45]. And library historian Mary Niles Maack later found that, from 1960 to 1980, women faculty in accredited U.S. library school programs decreased from 55% to 41% [26]. This was precisely the period of digital technological change in the curriculum.

Enthusiasm within librarianship for adopting computers during the 1960s resulted in countless pilot projects and system proposals—most of them located within the same large academic and corporate sites where men held the greatest positions of power in librarianship. While few of these computer experiments proved to be long-lasting successes, they did serve to popularize a particular set of meanings for the push-button library which were linked to the gendered division of library labor. For example, one of the articles in Shera’s 1964 “woman’s guide to automation” claimed that while “what a librarian does is complex enough to defy a quick and simple resort to mechanization,” nevertheless this only applied to “the intellectual and not to the clerical processes of librarianship” [27]. Here the “intellectual” processes of librarianship were assumed to be (mostly male, mostly high wage) reference services, management, and administration, while the “clerical” processes of librarianship were assumed to be (mostly female, mostly low wage) cataloging and circulation. Another author in the same issue, University of Missouri librarian and punched-card pioneer Ralph H. Parker, argued that with automation in the library, “the greatest effect is upon routine clerical jobs such as typing, [the] use of calculating and adding machines, and filing. The things machines do best are usually those most boring to people.” Thus, in an argument similar to those made by many advocates of automation in other industries around midcentury, Parker assured his librarian readers that “in the actual situation, no one is likely to lose a job; he [sic] will rather be put to more fruitful work” [28]. Computers would automate away the (feminine) clerical and augment the (masculine) creative work—a root argument in almost every theory of the “new information society” from the 1960s onward [29].

What made this upskilling/deskilling argument unique in librarianship was the idea that the two efforts—automating the clerical and augmenting the conceptual—were tied procedurally and almost teleologically together, since the library automators of the 1960s firmly believed that “the success of [automated information retrieval] will in the long run depend on the successful automation of routine library records” [28, p. 753]. Producing new systems for information retrieval, and training the new librarians who would master these systems, was the key goal that both depended on and justified the automation of library clerical processes. And it was indeed a goal that could only be fulfilled, so the argument went, through cooperation by traditional (female) librarians with outside (male) experts—often from the defense industry where new mechanized systems of “documentation” had first been prototyped for organizing scientific and technical report literature. Or as the original designers of the World’s Fair “library of the future” exhibits, Joseph Becker and Robert Hayes, put it in the first-ever automation textbook for librarians in 1963, “librarians, documentalists, mathematicians, system designers, equipment manufacturers, operations researchers, and computer programmers” all needed to understand “how interwoven are their interests and how overlapping their responsibilities” [30].

This gendered split in the character of computerized library work could best be seen in one of the most salient metaphors in the literature of the time: that of clerical library work as “housekeeping.” For example, in 1970 Janet Freedman (a librarian at the Salem State College Library in Salem, Massachusetts) wrote in the Library Journal: “With most of the creative posts dominated by men, women are likely to be utilized for their ‘housekeeping’ talents in serials, acquisitions, and cataloging work, or for their ‘patience and warmth’ in school libraries and children’s departments” [31]. A year later, librarian Helen Lowenthal wrote in the same trade publication that “women are recruited for the bottom and men for the top” in librarianship, where “those of us in public services play mother to our patrons and those in technical services ‘keep house’ within our institutions” [32]. Such metaphors and stereotypes were increasingly operationalized through the 1960s and 1970s into gender-based personality tests used for both admissions to library schools and hiring in library jobs. On one such personality test, the California Psychological Inventory, one of the questions that purported to indicate femininity if answered “True” was itself “I think I would like the work of a librarian” [33]. And there were plenty of librarians—even women librarians—who held essentialist views of women as being biologically better suited to so-called technical services work (like cataloging). Librarian F. Bernice Field argued in the 1971 compilation Women in the Library Profession that women were preferable as managers of technical services departments because “generally women have more aptitude than men for the kind of detail” needed for technical services operations and also because “men … tend to move into general administration and are, therefore, not dependable for long-range assignments” in technical services [34].

As a vocal part of the “second wave feminism” movement, female librarians who did not hold such essentialist views did much to publicize and rectify their disproportionate power position and disadvantaged salary position through the 1970s. But few of these efforts focused on technology, even though this was precisely the period when computer terminals were initially introduced to research and public libraries on a large scale (first behind the circulation desk for cooperative cataloging ventures, and later in front of the circulation desk for patrons to use as a new electronic catalog). Such technology received hardly a mention at the 1974 ALA preconference on the status of women in librarianship, where a keynote presentation on discrimination statistics by Anita Schiller was followed by panels on self-image, education, affirmative action, career development, unions, organizing, and tactics [17, p. ii]. Most of the agenda was focused on either achieving pay equity for rank-and-file librarians (through unionization if necessary) or moving librarians up the career ladder to management positions. Now and then an observer might call for women to improve their wage situation by learning new technical skills, as when Philadelphia library director Herman Greenberg argued in the 1975 “Melvil’s Rib” symposium on women in librarianship that women should “apply for education and training in computer sciences, a relatively new field in most libraries, so that when information sciences begin to be utilized by a majority of libraries, they will be in a position where their skills are required by the employer” [35]. But such calls were rare (and often fell into a rather simplistic “human factors” analysis of gender discrimination as based on differing skill sets). The situation had not changed much by 1984, when a radical bibliography of library labor and gender issues, On Account of Sex, listed not a single work dealing with library computerization or technology from 1977 to 1981 [36]. By the late 1980s the history of feminism within librarianship was itself a topic of academic research, with a content analysis of some 250 articles on women and librarianship from 1965 to 1985 revealing almost no connection to the literature on library technology [37].

LIBRARY TECHNOLOGY AND LIBRARY LABOR, 1980–1990

Librarians concerned with gender eventually began to talk about library technology in cataloging. The library catalog often served as a touchpoint connecting debates over the future of the library, as it was the one concrete tool shared by library staff and library patrons. In a way it served as a “boundary object” between these two communities of practice. The catalog was a constant point of translation between a patron’s view of an information space and a librarian’s view of that same domain of knowledge. But even within librarianship, front-desk reference librarians who used the catalog on a daily basis to help patrons locate materials might lament the rushed work of the back-office catalogers who built the finding aid in the first place (just as catalogers might complain that reference librarians rarely made use of the careful cross-referencing and controlled languages they provided to them). And through all of its technological changes—from typewritten cards in drawers to glowing ASCII characters displayed on computer monitors—the library catalog has tended to stand as a concrete symbolic example of the state of technological sophistication in a library (Fig. 7.2). After 1981, when the Library of Congress closed its own card catalog, a library using card drawers might be seen as “behind the times,” while a library using a CRT-based catalog network might be celebrated for being on the “cutting edge.” Even though this cataloging technology debate didn’t begin as a critical response to gender disparities, it ended up that way.

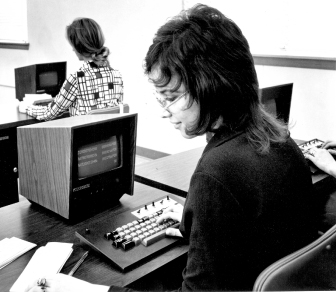

Figure 7.2. Librarians (and others) saw the future in “glowing ASCII characters.” A 1971 vision of the future includes “a solid-state keyboard and cathode ray tube (CRT) display,” with up to four lines of 32 characters.

(Courtesy of Charles Babbage Institute.)

In the early 1980s, university library director Ruth Hafter argued in her doctoral dissertation that the computer-based, networked cataloging technology of agencies like OCLC could potentially deskill catalogers, since more cataloging was performed remotely (and anonymously) than ever before. Still, she didn’t specifically link this deskilling to gender. Hafter’s original cataloging study was based on 68 interviews with catalogers and managers at six academic libraries on the West Coast [38, p. 6]. Published in 1986, her book pointed out that while the catalog was regularly praised as “the most valuable and unique resource of each library,” catalogers themselves were often feared to be the least capable of library professionals, with cataloging departments stereotyped as “a quiet haven for those unable to make it in other areas of the library and/or academic world” [38, pp. 3, 12]. The availability of electronic catalog records through OCLC seemed to exacerbate this contradiction. At the same time that expensive technology was being installed to facilitate cataloging in times of tight library budgets during the recessions and tax revolts of the late 1970s and early 1980s, catalogers themselves seemed to be devalued, since the “routine and standardized records available in the data base” could now “be manipulated by library assistants and clerks, rather than catalogers” [38, p. 125]. This was the deskilling of the “housekeeping” work that many outside library computing advocates had long hoped for, and that many librarians themselves had long feared.

But Hafter’s analysis of the changes wrought by computerized cataloging was more complicated than simple deskilling. At the same time that “deprofessionalization” might be occurring in cataloging, Hafter suggested that “the collegial structure of the network tends to mitigate the impact of the controls placed upon catalogers and, in many instances, restores lost authority to them,” especially in “self-monitoring of cataloging by accepted leaders of the profession” [38, p. 127]. In other words, catalogers could now peer-review each others’ work. Or as she put it in a 1986 article in College & Research Libraries, “while the network has sowed the seeds for the deprofessionalization of cataloging, it has also reaped the crop of the new breed of born-again catalogers” [39]. Notably, Hafter’s conclusion entirely omitted any kind of gender analysis. For Hafter, neither the threat of deprofessionalization nor the promise of reprofessionalization were driven by the well-known gender disparities within librarianship. Instead, they were driven by a longstanding library management argument about what kind of cataloging to perform, at what cost, and within what kind of spatial, technical, skill, and wage division of labor—and contextualized within a very particular tight economic environment, where shrinking budgets and inflationary pressures motivated those library managers to see computer networking as a key labor-saving measure.

Hafter’s study might never have been brought to bear on the questions of gender in librarianship had it not been for SUNY library science professor Suzanne Hildenbrand. A few years after Hafter’s book was published, at a 1989 Simmons College symposium on recruiting, educating, and training cataloging librarians, most of the speakers argued that cataloging was in a “crisis” because it was seemingly unable to attract either the career interest of library students or the budget attention of library administrators. Given the profession’s very public focus on OCLC as a supposed technological fix to the perennial problem of cataloging backlogs during the early 1980s, it was arguably not surprising that the cataloging subfield took a downturn a few years later. But rather than see the cataloging crisis through the logic of labor and technology, Hildenbrand—herself a feminist historian of librarianship—connected the crisis first and foremost to gender. She argued that “the crisis in cataloging today is linked to a largely unexplored aspect of sexual stratification within librarianship,” and that the problems faced by catalogers, such as low wages and low status, “reflect the fact that it is an even more female-intensive occupation than librarianship as a whole” [40, p. 207].

Hildenbrand admitted that evidence to back up her arguments was scarce. Survey data indicated that catalogers’ salaries trailed reference librarians’ by approximately $550 [40, p. 212]. But most of her claims were rooted in vivid anecdotal evidence of the working conditions within the cataloging departments of the same large academic and corporate libraries that were the original focus of the automation experts: “Every time I go into the cataloging department at one major university I am struck by its similarity to the old time typing pools in the insurance companies. It is a big open area with all these people at their desks filing cards and papers. I think it is significant that only two people in this large department have offices they can go into and close a door to have privacy. Only two people have their own telephone line” [41]. Besides such particular but decontextualized evidence, Hildenbrand cited Hafter’s 1986 study in what Hildenbrand called “a decline in the status of catalogers since the introduction of network cataloging,” saying that by now “everyone is familiar with descriptions of contemporary cataloging departments that sound like institutional backwaters where outdated modes of management prevail in a kind of white collar sweatshop” [40, p. 213].

Hildenbrand’s anecdotal evidence may have pointed to a deprofessionalizing crisis, but where was the gender link? Hildenbrand found this through library education, where she claimed cataloging has been pushed to the periphery even though demand for catalogers was still strong. This argument invoked gender in two ways: first, Hildenbrand pointed out that, even after the feminist agitation of the 1970s, “library educators are predominantly men, while practitioners are predominantly women,” citing 1988 survey data still listing library school faculties as 55% male and 45% female [40, p. 215]. Second, Hildenbrand argued that at accredited U.S. library schools in 1983, cataloging was listed as a teaching specialty of 12% of female faculty, but only 5% of male faculty [40, p. 211]. Thus, it was up to a minority of female faculty to teach a minority of classes on cataloging for a minority of (presumably disproportionately female) students.

Absent solid evidence, as Hildenbrand herself admitted, “one must rely on impressions” [42]. Drawing on a very active history of liberal feminism within librarianship, where the stark disparities in comparative salaries, management positions, and library school professorships had been carefully and powerfully documented, Hildenbrand fit the newest “crisis in cataloging” into these same arguments. But just as Hafter’s arguments about cataloging being polarized into a deprofessionalized clerical mass and a reprofessionalized management elite really weren’t rooted in any systematic gender analysis, Hildenbrand’s arguments about cataloging being gendered really weren’t rooted in any systematic technology analysis.

It took a third library labor researcher, University of Western Ontario library science professor Roma Harris, to connect the arguments about gender discrimination and computer automation in 1992—a quarter century after the twin discussions about technology and gender began in the late 1960s. Both in her influential monograph Librarianship: The Erosion of a Woman’s Profession and in a companion article in the journal Computers in Libraries, Harris put forth a two-part hypothesis about how technology and gender worked together in librarianship [43,44]. First, Harris argued that the more “masculine” tasks within librarianship—“those involving technology and management”—were more highly valued than the more “feminine” tasks like children’s services and cataloging [43, p. 1]. Second, Harris claimed that after decades of library automation and networking, especially the development of OCLC, the largely female specialization of cataloging was “undergoing a process of ‘deprofessionalization’ or ‘deskilling’ ” (selectively drawing from Hafter’s arguments) [43, p. 121]. Harris recommended that “librarians must give themselves credit for what they know and put a stop to the process of shunning the female-intensive aspects of their work,” instead “acknowledging that tasks, such as children’s librarianship and cataloging, are central to this field and as worthy of status and financial reward (if not more so) as computing expertise” [43, p. 164]. These 1992 arguments continued to exert influence in the library literature into the 21st century, taking on the status of a “standard narrative” about the way technology and gender interacted in librarianship through the 1970s and 1980s.

But as I have tried to demonstrate in this chapter, this narrative is not exactly accurate. In fact, the Harris thesis contains a rather subtle contradiction. On the one hand, the weaving of computer technology into librarianship is cast both as an essentially masculine project (pitted against what are cast as essentially feminine projects of serving users, especially children, to address their literacy and information-seeking needs), and as a project that brings men themselves into librarianship—in key positions of power and authority over women—from the outside fields of information science, computer science, and business management. But on the other hand, this development of library computer technology is cast as a project mostly affecting women, meant to create a “pink-collar sweatshop” of low-paid workers pinned to networked computer terminals in highly rationalized and contingent back-office data management jobs within librarianship (Fig. 7.3). Harris herself expressed this contradiction when she revisited her thesis in 2000, arguing that “in librarianship, where technological change dominates the workplace, we find that men are more likely than women to be seen as the keepers of technology. They derive status from their association with technology. On the other hand, women’s jobs, most of which now also require an intensive use of technology, are nevertheless seen to be easier, to involve less advanced knowledge, and somehow carry a lesser weight” [45]. So in this view, computers are “upskilling” when applied to the male division of labor, and “deskilling” when applied to the female division of labor. As we have seen, this understanding of computer technology as polarizing within the library division of labor actually has a long history.

Figure 7.3. Information automation or “pink-collar sweatshop.” NCR tag printer as “integral part” of information system. While “unit automatically produces a wide variety” of labels, woman’s labor remained.

(Courtesy of Charles Babbage Institute.)

Harris’s first argument, that the interests of (mostly male) technologists from outside the profession of librarianship were firmly oriented toward restructuring the technical and skill division of labor within the (mostly female) profession of librarianship was indeed accurate; but it was also unsurprising. Such a project had been underway quite openly for at least three decades before Harris articulated it in 1992, wrapped so far into the core assumptions of library systems development in the large academic and corporate research libraries that it ceased to be discussed. Harris’s second argument that the computer-based, networked cataloging technology, which originated in the 1970s with OCLC, specifically deskills women catalogers in the library drew directly on the work of Hafter and Hildenbrand from the 1980s. Harris’s insight was to combine these two arguments together to claim that the alleged deskilling changes wrought by computerized cataloging technology were disproportionately concentrated on women within librarianship. In other words, the original polarized dream of computerization—both automation of clerical drudgery and augmentation of conceptual creativity—had succeeded for male library workers but failed for female library workers.

Neither Harris, Hildenbrand, nor Hafter contextualized their concerns about cataloging in the broader history of library technology and labor. But the drive to rationalize cataloging into what became known as “technical services,” splitting out the lower-paid, lower-status, and lower-skill clerical work of catalog material production from the higher-paid, higher-status, and higher-skill creative work of defining the actual bibliographic metadata that would be stored in catalog materials, began long before computerization and was motivated by more than patriarchal power relations. As early as 1901, in fact, when the Library of Congress began selling complete printed copies of its own 3 × 5 catalog cards to subscribing libraries, librarians had argued over whether cataloging involved clerical transcription or creative production. As Mary Salome Cutler Fairchild, a librarian who taught cataloging in Dewey’s own library school, wrote in the Library Journal in 1904, “women are as well fitted as men for technical work, even the higher grades of cataloging,” because of their “greater conscientiousness, patience, and accuracy in details”; but they were “generally preferred to men or boys in the routine work of a library,” because they were “more faithful and on the whole more adaptable” [46].

Gender relations have been an active if unrecognized force within librarianship for over a century [47]. But we still need to understand how this history of labor and technology has been intertwined with the production and reproduction of gender relations. The uses of technologies within librarianship do affect social relations, and social relations within librarianship do affect the uses of technologies. This basic insight—a fundamental understanding of current history of technology research—can help us reconstruct a more historically grounded narrative of computers, libraries, and gender that weaves the questions concerning cataloging into the larger labor processes within libraries—and into the larger meaning of the library itself.

CONCLUSION: FROM CATALOGING TO METADATA

Critiquing the earnest arguments of scholars and practitioners regarding computers, gender, and librarianship for lacking theoretical grounding or historical contextualization is useful only if it can point to a more productive way of conceptualizing this complicated relationship between social change (second-wave feminism in librarianship), technological change (networked computerization in library catalog production), and political-economic change (organizational and labor restructuring in library administration and budgeting). In the final section of this chapter, I want to suggest four ways that a broader, more gender- and labor-aware history of technology can be used to reinterpret this debate.

1. Consider all of librarianship as a “technology,” not just the computerized parts.

From the 1960s to the 1980s, networked computer technology has been the main kind of “technology” under debate within librarianship. Thus, technology and gender were only analyzed together within librarianship once cataloging labor moved to the networked and computerized system of OCLC. But cataloging, in all of its historical forms, is a technology in its own right. The technological innovation (and subsequent standardization) of the unit-card catalog system of the late 19th century, together with preexisting technological systems of print production and postal transport, was what enabled the Library of Congress to turn the “technological fix” of the card catalog into the “spatial fix” of centrally producing catalog records and then shipping them out to subscribing libraries. This publicly funded, nonprofit catalog production network, as well as the privately owned, for-profit competitors that followed it, represented the first “information revolution” in cataloging. It set into motion a whole series of debates, involving both men and women, over the proper place of cataloging practice within library science, leading in midcentury to a redefinition of cataloging from a humanistic, conceptual activity requiring classically trained subject experts in academic settings, to a routinized, manual activity requiring only minimally trained clerical workers of the new “technical services” department. And even after the computerization projects of MARC in the 1960s and OCLC in the 1970s—combining the “technological fix” of machine-readable catalog records with the “spatial fix” of decentralized cooperative cataloging labor—libraries initially sought virtual catalog records on magnetic tape specifically so they could produce new material catalog products, on analog media such as microfiche cards or bound paper volumes. In a way, all library processes—from circulation management to reference service to literacy instruction—are “technologies” of a particular sociotechnical sort, as they involve complex combinations of material artifacts, human agents, and codified systems of thought. Thus, a longer-term historical investigation that crosses all of these boundaries is called for, rather than an exclusive focus on computation.

2. Consider the object of library technology not as “data” but as “metadata.”

If the various processes taking place within a library (like cataloging) can be considered as sociotechnical information systems, then the library as a whole might be considered as a sociotechnical information network. We might even scale this idea up to consider the whole of librarianship, whether academic, public, school, or corporate, as part of a sociotechnical information internetwork—an idea not too far from the current claims of digital library advocates that their organizations represent crucial components of “cyberinfrastructure” [48]. But systems, networks, and internetworks suggest some object of interaction, some unit of circulation. What moves through such library infrastructures? In the late 19th century, an observer might respond that the object of circulation was, quite obviously, the book. Today, it has become more commonplace to imagine a general unit of “information” (an article, an image, a fact) moving between library staffers and library patrons. But as the historical example of cataloging illustrates, the true resource of the library cyberinfrastructure is not data, but metadata—information about the myriad books and magazines, reports and theses, music and video, multimedia and hypermedia of all sorts, which libraries collect, organize, store, and circulate. For example, in cataloging, as Hafter pointed out in the early 1980s, “rules and procedures change” over time in a myriad of ways: subject headings may need to be adjusted for modern terminology, the latest scientific thought, or innovative search practices; user populations for individual libraries may evolve in their needs and sophistication; budgets available to cataloging fluctuate over time; the status conferred by having a “complete” or “detailed” catalog may vary; and, of course, the very technology for entering, storing, and accessing the catalog metadata may change, affecting labor costs, turnaround times, and production techniques [38, pp. 11–12]. Following the metadata through such processes—how it is made visible and invisible, valued and devalued, rendered in both physical and virtual forms—allows the historian of technology to analytically connect practices of librarianship across vastly different institutional, functional, social, and technological contexts.

3. Recognize that it takes human labor to produce, reproduce, and use metadata.

Metadata is only a useful historical unit of analysis if it can help illuminate the human practices and human decisions underpinning the library mission. These are questions of metadata labor—the work and expertise required to create, organize, store, and use metadata, but also to recreate, reorganize, restore, and reuse it (as the social, organizational, or technological conditions of librarianship change over time). In other words, metadata helps link the labor of the cataloger in the back office to the labor of the reference librarian in the front office. Thinking about metadata as requiring constant labor through all of these moments of production, reproduction, and use points not only to the necessary costs of that labor (in time and money) but also to the unrecognized value of that labor (in skill and experience) when it is put to work helping library patrons navigate a perpetual “information crisis” of abundant materials, which are themselves of little value if they can never be located when needed. Such information labor may even shift, with the passage of time and the development of technology, from producer to user, as patrons navigate computerized search screens and digital databases, which once would have demanded high-paid, high-skilled expert assistance [49]. Again, particularly in the history of cataloging and computation, such a focus can help us understand how librarians of the 1960s through the 1980s, both male and female, often saw (and split) themselves more as new-economy “information intermediaries” with high levels of skill (e.g., doing pay-per-minute or pay-per-record private database searches for patrons) rather than old-style “technical assistants” working with rote online systems to download and adapt centrally produced, clerical cataloging data.

4. Question gendered meanings around the different moments of metadata labor.

Finally, these three assumptions—that the library is itself a technology, that the object of that technology is metadata, and that profound labor is required to manage that metadata—can lead us back to the original questions of gender and computing within library history. But it is not enough to simply assert that “computing was masculine” and “librarianship was feminine” because of the demography of the participants (more males in computing, more females in librarianship). We should say something about the cultural assumptions around the social contexts in which those participants worked: to explain how these hegemonic genderings are produced, reproduced, and resisted. Are computer centers and computer programming gendered masculine? Are humanities libraries and reference services gendered feminine?

From the 1960s onward, library computing projects were structured by both an institutional and a spatial division of labor in librarianship, with digital systems first prototyped by a few large academic and corporate libraries, and only later consumed by a much larger number of smaller public and school libraries. But as the feminist librarians of the 1970s so conclusively demonstrated, the gender division of library labor has been structured by this same institutional and spatial division of labor, with proportionately more men in academic and corporate libraries than in public and school libraries. Within the library, the gendering of the computer may link more to the administrative imbalance within librarianship—with technology seen as a rationalizing management strategy—than to the masculine nature or origin of that technology itself.

Ideas of masculinity and femininity still have power within the library internetwork, especially in terms of gendered labor roles. Not just in the 1980s, but all through library history, the application of technology to so-called housekeeping work in the library was often targeted to eliminate or restructure (deskill, devalue, or deprofessionalize) the lowest-status, lowest-wage, most material kinds of library tasks—tasks that were indeed disproportionately performed by women (often by design). In the same way, while automation of “knowledge” work was often imagined as augmenting and uplifting the highest-status, highest-wage, and most conceptual work within librarianship, in this as in other fields, such upgraded work was disproportionately performed by men (again by design). But librarianship adds another wrinkle to this standard story. Just as back-office “housekeeping” clerical labor has long been gendered feminine in myriad occupations, so has its opposite—front-desk “nurturing” service and education labor—long been assumed to be the proper domain of women. If the basic promise of clerical computer automation was to open up more space and time for conceptual computer augmentation, how has the service-oriented work of librarianship negotiated a gender dynamic that might be both masculine and feminine? By connecting the back-office moment of metadata production to the front-desk moment of metadata use, perhaps a new relationship between technological change and gender construction in computing can be seen.

The overall story of libraries, computers, and women is important precisely because it demonstrates that simply adding information technology to an occupation doesn’t produce predictable, deterministic results. The way computers were understood and ended up being used within librarianship was quite clearly tied to contemporary notions of the proper gender roles of male and female library professionals. From the 1960s to the 1980s, both ideas about the proper place of women and ideas about the proper use of technology were changing at the same time. Exploring the intertwined history of women, computers, and libraries illustrates how moments of new technological possibility are often moments of social reflection and change as well, precisely because our produced technological environments and our worlds of social meaning are so tied up in each other. And this less-well-known history of gender and computing might be especially relevant today, with printed books rapidly converging with computer interfaces through corporate ventures like Amazon Kindle and Google Print. I doubt that the library is doomed to irrelevance in the new networked computing environment. But I suspect that the fate of the library in this digital future of reading will once again hinge, as it always did, on the labor of women.

REFERENCES

1. James Cortada, The Digital Hand, Volume III (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

2. See, for example, Paul N. Edwards, “The Army and the Microworld,” Signs, Vol. 16, No. 1 (1990): 102–127; Jennifer Light, “When Computers Were Women,” Technology and Culture, Vol. 40, No. 3 (1999): 455–483; Nathan L. Ensmenger, “Letting the ‘Computer Boys’ Take Over: Technology and the Politics of Organizational Transformation,” in Aad Blok and Greg Downey, eds., Uncovering Labour in Information Revolutions (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2004).

3. See, for example, Thomas Augst and Wayne A. Wiegand, eds., The Library as an Agency of Culture (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2003); Michael H. Harris, History of Libraries in the Western World, 4th ed. (Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1995); Wayne A. Wiegand and Donald G. Davis, Jr., eds., The Encyclopedia of Library History (New York: Garland, 1994).

4. Greg Downey, “Virtual Webs, Physical Technologies, and Hidden Workers,” Technology and Culture, Vol. 42, No. 2 (2001): 209–235.

5. Greg Downey, “The Librarian and the Univac: Automation and Labor at the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair” in Catherine McKercher and Vincent Mosco, eds., Knowledge Workers in the Information Society (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2007).

6. Jesse Shera, (Introduction to special issue on library automation) Wilson Library Bulletin, Vol. 38 (May 1964): 741–742.

7. Jesse Shera, “Without Reserve,” Wilson Library Bulletin, Vol. 38 (May 1964): 781.

8. See, for example, Anne Witz and Mike Savage, “The Gender of Organizations,” in Mike Savage and Anne Witz, eds., Gender and Bureaucracy (Cambridge, UK: Blackwell, 1992); Joan Acker, “From Sex Roles to Gendered Institutions,” Contemporary Sociology, Vol. 21, No. 5 (1992): 565–569.

9. Katherine Murphy Dickson, Sexism and Reentry: Job Realities for Women Librarians (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1997).

10. Hope A. Olson and Amber Ritchie, “Gentility, Technicality, and Salary: Women in the Literature of Librarianship” in Betsy Kruger and Catherine Larson, eds., On Account of Sex: An Annotated Bibliography on the Status of Women in Librarianship, 1998–2002 (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2006).

11. Katharine Phenix, “Women Predominate, Men Dominate,” Bowker Annual, Vol. 29 (1984): 83.

12. See, for example, Marie L. Radford and Gary P. Radford, “Power, Knowledge, and Fear,” Library Quarterly, Vol. 67, No. 3 (1997): 250–266; Cheryl Knott Malone, “Imagining Information Retrieval in the Library,” IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, Vol. 24, No. 3 (2002): 14–22.

13. Arnold P. Sable, “The Sexuality of the Library Profession,” Wilson Library Bulletin, Vol. 43 (April 1969): 751.

14. Sally H. McCallum, “MARC,” IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, Vol. 24, No. 2 (2002): 34–49.

15. Anita R. Schiller, with James W. Grimm and Margo C. Trumpeter, Characteristics of Professional Personnel in College and University Libraries (Springfield: Illinois State Library, 1969), p. 2.

16. Pat Schuman, “Status of Women in Libraries,” Library Journal (August 1970): 2635.

17. Betty-Carol Sellen and Joan K. Marshall, eds., Women in a Woman’s Profession: Strategies, proceedings, American Library Association Preconference on the Status of Women in Librarianship (July 1974).

18. Kathleen L. Maciuszko, OCLC (Littleton: Libraries Unlimited, 1984).

19. See, for example, Nina E. Lerman, Arwen Palmer Mohun, and Ruth Oldenziel, “The Shoulders We Stand on and the View from Here,” Technology and Culture, Vol. 38, No. 1 (1997): 9–30; Judy Wajcman, “The Feminization of Work in the Information Age,” in Mary Frank Fox, Deborah G. Johnson, and Sue V. Rosser, eds., Women, Gender, and Technology (Urbana: University of Illinois, 2006), pp. 80–97.

20. Betty Jo Irvine, Sex Segregation in Librarianship: Demographic and Career Patterns of Academic Library Administrators (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1985), p. 9.

21. Alice Bryan, The Public Librarian (New York: Columbia University Press, 1952).

22. Suzanne Hildenbrand, “Library Feminism and Library Women’s History,” Libraries & Culture, Vol. 35, No. 1 (2000): 51–67.

23. Helen W. Tuttle, “Women in Academic Libraries,” Library Journal (September 1971): 2594–2596.

24. Raymond L. Carpenter and Kenneth D. Shearer, “Sex and Salary Survey,” Library Journal (15 November 1972): 3682–3685.

25. Anita Schiller, “Women in Librarianship,” Advances in Librarianship, Vol. 4 (1974): 104–147.

26. Mary Niles Maack, “Women as Visionaries, Mentors, and Agents of Change,” in Joanne E. Passet, ed., Women’s Work: Vision and Change in Librarianship (Urbana: University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign GLIS, 1994), p. 111.

27. Alan Rees, “New Bottles for Old Wine: Retrieval and Librarianship,” Wilson Library Bulletin Vol. 38, No. 9 (May 1964): 773.

28. Ralph H. Parker, “What Every Librarian Should Know About Automation,” Wilson Library Bulletin, Vol. 38, No. 9 (May 1964): 754.

29. Nick Dyer-Witheford, Cyber-Marx: Cycles and Circuits of Struggle in High-Technology Capitalism (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1999).

30. Joseph Becker and Robert M. Hayes, Information Storage and Retrieval: Tools, Elements, and Theories (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 1963), p. x.

31. Janet Freedman, “The Liberated Librarian?” Library Journal (1 May 1970): 1709–1711.

32. Helen Lowenthal, “A Healthy Anger,” Library Journal (1 September 1971): 2597–2599.

33. Jody Newmyer, “The Image Problem of the Librarian,” Journal of Library History (1976): 44–67.

34. F. Bernice Field, “Technical Services and Women,” in Russell E. Bidlack, ed., Women in the Library Profession: Leadership Roles and Contributions (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 1971), p. 15.

35. Herman Greenberg, “Sex Discrimination Against Women in Libraries,” in Margaret Myers and Mayra Scarborough, eds., Women in Librarianship: Melvil’s Rib Symposium (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Graduate School of Library Service, 1975), p. 52.

36. Kathleen Heim and Katharine Phenix, “The Women’s Movement Within Librarianship, 1977–1981,” in Kathleen Heim and Katharine Phenix, eds., On Account of Sex: An Annotated Bibliography on the Status of Women in Librarianship, 1977– 1981 (Chicago: American Library Association, 1984).

37. Christina D. Baum, Feminist Thought in American Librarianship (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1992).

38. Ruth Hafter, Academic Librarians and Cataloguing Networks: Visibility, Quality Control, and Professional Status (New York: Greenwood Press, 1986).

39. Ruth Hafter, “Born-again Cataloging in the Online Networks,” College & Research Libraries, Vol. 47 (July 1986): 360–364.

40. Suzanne Hildenbrand, “The Crisis in Cataloging: A Feminist Hypothesis” in Sheila S. Intner and Janet Swan Hill, eds., Recruiting, Educating and Training Cataloging Librarians (New York: Greenwood Press, 1989).

41. Sheila S. Intner and Janet Swan Hill, eds., Cataloging: The Professional Development Cycle (New York: Greenwood Press, 1991), p. 71.

42. Suzanne Hildenbrand, “Women’s Work Within Librarianship,” Library Journal, Vol. 114 (1 September 1989): 153–155.

43. Roma Harris, Librarianship: The Erosion of a Woman’s Profession (Norwood, NJ: Ablex, 1992).

44. Roma Harris, “Information Technology and the De-skilling of Librarians,” Computers in Libraries, Vol. 12, No. 1 (January 1992): 8.

45. Roma M. Harris, “Understanding Gender Relations in the Librarianship of the 1990s,” in Betsy Kruger and Catherine A. Larson, eds., On Account of Sex: An Annotated Bibliography on the Status of Women in Librarianship, 1993– 1999 (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2000), pp. xix–xx.

46. Mary Salome Cutler Fairchild, “Women in American Libraries,” Library Journal (December 1904): 157–162.

47. Mary Niles Maack, “Gender Issues in Librarianship,” in Wayne A. Wiegand and Donald G. Davis, eds., Encyclopedia of Library History (New York: Garland Publishing, 1994).

48. Paul N. Edwards, Steven J. Jackson, Geoffrey C. Bowker, and Cory P. Knobel, Understanding Infrastructure (Arlington, VA: National Science Foundation, 2007).

49. Bryan Pfaffenberger, Democratizing Information: Online Databases and the Rise of End-User Searching (Boston: G.K. Hall & Co., 1990).