11

Programming Enterprise

Women Entrepreneurs in Software and Computer Services

Few chief executives have been higher profile than Hewlett-Packard’s (HP) leader from 1999 to 2005, Carleton “Carly” Fiorina. In 1996, as AT&T Executive Vice President for Corporate Operations, she oversaw the largest initial public offering in the United States to that time—Lucent [1]. Her achievements at AT&T and Lucent helped propel her to the top leadership post at HP. With this appointment, she became the first woman to run a Dow 30 company and the first woman CEO and Board Chair of an IT giant [2]. A board battle with Walter Hewlett (son of co-founder William Hewlett) over Fiorina’s decision to acquire Compaq, and other differences of opinion on strategy, contributed to her controversial ouster.

A year before Fiorina took over at HP, Margaret “Meg” Whitman became CEO of a small web-based auction firm, eBay. Whitman led this company for a decade, turning it into an e-commerce powerhouse. It brought together buyers and sellers of nearly every imaginable product in a virtual marketplace, taking a commission on each sale and operating with extremely low overhead. As the dot.com collapse of 2000 to 2002 decimated many e-commerce firms and scarred countless others, eBay emerged relatively unscathed. In fiscal 2006 eBay had nearly $6 billion in revenue and more than $1.2 billion in net income [3]. In January 2008 Whitman stepped down from eBay.

While no other women have reached the level of recognition and stature in the IT world as Fiorina and Whitman, fully one-tenth of Fortune’s 2008 “50 Most Powerful Women” were high ranking executives at IT giants—from Safra Catz, the co-president of Oracle, who oversees day-to-day operations for this leading enterprise software firm, to Ginni Rometty, IBM’s Senior Vice President for Global Business Services, who runs the $18 billion division critical to IBM’s future growth [4]. One of the primary reasons these leading women IT executives have been in the spotlight, however, is because many glass ceilings remain firmly in place and there are relatively few women in these top posts. Another important reason is that these achievements, while rare and generally the result of overcoming numerous obstacles, are a complete break from the past. From the origin of the computer industry in the early 1950s—and the software and services industry roughly a half-decade later—through the 1980s there were meaningful though varying barriers to the entry for women into large computer and software companies, and almost insurmountable ones to moving high up the corporate ladder at these firms.

This chapter is focused on an alternative path of women to leadership positions in the IT world. It concentrates on women entrepreneurs from the 1960s through the 1980s in the software and computer services industries—the companies they founded and ran and their leadership within trade associations for these industries. There are many challenges to unearthing this important history. Virtually no archival resources exist to provide records on these firms, and little archival material is available on IT trade associations. An exception to the latter is the ADAPSO Records at the Charles Babbage Institute. This collection and a series of oral histories with women IT entrepreneurs are the foundational resources for this chapter.

The history of women IT entrepreneurs is not only uncharted terrain; it is also a subset of the larger history of women entrepreneurs that has been grossly understudied. (There is a growing literature on women entrepreneurship in the past decade—and a surge of scholarship on women and microenterprise in the developing world. This literature generally analyzes contemporary situations or recent events, advocates particular policies or practices, and ignores longer-term historical developments [5].) Among the factors contributing to the dearth of historical literature on women entrepreneurs are the particular trajectories of the fields of business history and women’s history. Long following the lead of Alfred Chandler, business historians have focused on large firms [6]. Even as the field has recently broadened, the literature that examines the origin of small businesses is almost exclusively limited to studies of the few firms that grew to become corporate giants [7]. Meanwhile, the fields of women’s history and gender history have grown rapidly in the past three decades, along with histories concentrated on race and class, as part of the “new social history.” In this environment, women’s labor history has thrived as a field [8]. But few historians have focused on women elites in the business world [9]. Hence, the history of women who founded and led small to mid-sized software and computer services businesses, and provided leadership to trade associations in these industries, has remained outside the dominant currents of women’s history and business history.

This chapter will first examine the broader environment for IT employment for women. It will then turn to three case studies of women (Luanne Johnson, Grace Gentry, and Phyliss Murphy), who ran successful small software and computer services businesses for years (Argonaut Information Systems, Gentry, Inc., and Phyliss Murphy & Associates), and also were leaders in two trade organizations: the Association for Data Processing Services Organizations (ADAPSO) and the National Association of Computer Consultant Businesses (NACCB). (In discussing the NACCB, it will also profile the long-time executive director, Peggy Smith—who previously was one of three founders of an IT consultant brokerage.) These case studies not only demonstrate the insight, creativity, resourcefulness, and skill of these enterprising women to found and lead their businesses, but also the unique capabilities they brought to trade associations to enable them to add value to their member companies.

WOMEN’S EMPLOYMENT IN LARGE IT ENTERPRISES

By the 1960s the universe of computer occupations not only included those at computer firms (like IBM, Control Data, etc.), but also the computer or data processing operations of numerous companies in a growing number of industries (including insurance, banking, and aerospace). At both computer companies and firms with computer departments, computer occupations ranged from keypunchers and operators to programmers, systems analysts, and computer engineers.

Keypunchers were a new form of clerical workers; they were low paid and predominantly women from the start. The computer operator category changed over time—generally declining in responsibility, skill, prestige, and earnings—from those who did complex plug board programming in the late 1940s (“ENIAC girls”) to those who did routine mechanical and clerical tasks in the 1960s. (Deskilling and division of labor accelerated during the 1960s and operators of computers typically came to be similar in responsibilities and status to other types of machine operators (programming was left to the programmers and there was not a career path to advancement; see Chapter 5 in this volume) [10, pp. 63–83].) Further up the hierarchy were programmers and systems analysts. By the 1950s and 1960s programmers were clearly higher than operators, but it was a new occupation of somewhat uncertain stature and midlevel compensation [11]. In these years, it was usually lower paid and lower status than computer engineers, and it required less education. Programmers came from a range of fields and did not always need a college degree to get hired—often scoring well on an aptitude test was enough. Systems analysts sometimes graduated from the ranks of skilled programmers and, over time, increasingly had college or graduate training in mathematics, business, engineering, or computer science. (More gradations have developed, including “software engineers” and, more recently, “software developers.” For the period covered in this chapter, most software workers fell in the programmer, systems analysts, sales, or executive ranks.) They analyzed problems, procured equipment, designed and oversaw data processing systems, and supervised a number of programmers. They also served as intermediaries between the decision-making users of data (business analysts/managers/executives) and the programmers [10, pp. 63–83].

In the mid-1950s the first software services firms arose to serve mainframe computer customer organizations. By the 1960s the services industry was thriving and included service bureaus (i.e., IBM’s spin-off Service Bureau Corporation, General Electric’s GEISCO, Tymshare, Inc.), facilities management firms (i.e., Electronic Data Systems), and diversified providers (i.e., Computer Science Corporation, University Computing Corporation). In the early to mid-1960s a number of services companies began producing software products (i.e., Applied Data Research’s Autoflow) [12]. Within a few years some firms were founded as software products businesses (i.e., Cullinane Corporation) [13]. Beginning in the mid-1970s an increasing number of IT services businesses supplied independent contractors to client organizations, representing a new area of the services industry (and a focal point of this chapter). All of these segments employed (or contracted with) numerous programmers and systems analysts.

Given this chapter’s focus on the software and computer services industries, it will concentrate on the occupations of programmers, systems analysts, and software/services top executives. Some of the small group of women who programmed the ENIAC or other mainframes for the government in the late 1940s continued to work at major computer firms in the 1950s, but women’s entry into the ranks of programmers generally was difficult during that decade. Joan Greenbaum, a programmer who later wrote on management theory in data processing, quoted a female physics graduate from the late 1950s: “The aerospace industry was growing fast and I really wanted to be a programmer, but women weren’t ‘good enough’ to be programmers. We were hired at 20 percent less than men and only allowed to set up the test cases” [10, p. 87]. By the 1960s opportunities opened up substantially for women as there was almost a perpetual “software crisis” resulting in, and partially defined by, a shortage of programmers. (Joan Greenbaum found it difficult obtaining professional work after graduating from college in 1963 in other fields, but after scoring well on a programming aptitude test, quickly received a programming job and, as she perceived it, instantly became a “professional.” The professional status of programmers, however, was contested terrain (see Chapter 6).) At this time, scoring well on aptitude tests could often lead to entry into the programming field for women, but hiring biases in favoring male applicants did not disappear, nor did biases in compensation or opportunities for advancement.

A survey published in Computerworld indicated that, in 1974, 13% of systems analysts and 20% of programmers were women [14]. A half-dozen years later, data from the 1980 census showed significant growth in these numbers: 22% of systems analysts and 31% of programmers were women [15]. In absolute terms, this represented major growth—as the number of programming jobs and systems analyst jobs increased by 94% and 80%, respectively, during the 1970s [15]. Increasingly in that decade, some employers ran advertisements that were specifically targeted at hiring women programmers (compare Fig. 1.1, 6.1, and 10.2) [16]. In general, there were geographical and industry differences and women tended to have higher relative representation in the lower paid, end-user industries as opposed to positions at computer and software companies [17].

A study of the earnings gap in the leading state for computer employment, California, indicated that female computer specialists (programmers and systems analysts) earned only 72% of male computer specialists. The researchers (Donato and Roos) conducting this study adjusted this raw figure for a variety of individual (age, education, etc.) and structural factors (industries, industry sectors, etc.) and concluded that women still only made 89% the compensation of men [15]. That women found it more difficult to gain employment at computer and software firms, and that throughout at least much of the industry women programmers and systems analysts made less than men, leads us to the cases of three women who initially worked for sizable corporations/organizations but then took a different path—starting their own software and computer services enterprises.

ARGONAUT INFORMATION SYSTEMS

Luanne Johnson was born in 1938 and raised in Orville, Ohio. Her father was a teacher; and she grew up with a deep interest in writing. She was an education major at Bowling Green State University when she took a sponsored trip to California as vice president of a Christian fellowship student organization. She loved California from the moment she arrived, especially the San Francisco Bay area, and decided to stay. Soon after, she got married. Having strong typing skills, Johnson was hired as a department secretary at University of California–Berkeley. She soon left Berkeley for several secretarial jobs in the private sector, before becoming a legal secretary with a downtown Oakland firm. Divorced by that time, and raising a daughter, she wanted the higher salary of legal secretaries. (This section, unless noted otherwise, is from the Luanne Johnson Oral History [18].)

In the early 1960s, a librarian friend encouraged her to take a programming aptitude test. She scored well and followed this with night school programming courses to earn a certificate from Heald College. Before long she was hired by Alameda County as a programmer trainee, along with two male trainees. While the two men complained about the compensation, she was making more than she had made as a legal secretary and was grateful for the opportunity to take programming courses at IBM—including Autocoder, FORTRAN, COBOL, PL1, and RPG. Alameda County transferred programmers around as needed on projects; and before long she was programming court calendars—the only group that had to take nightshifts from time to time. When Johnson, the only woman on this project, could not find a sitter, she would have to take her daughter to work at night and bundle her up to sleep on the couch in the women’s room, propping the door open with a box of IBM punch cards. The insensitivity to scheduling a single mother this way soon led her to seek other opportunities.

Through a friend, she learned of a programming job at a freight company. Soon she had several years of full-time programming experience and began to jump around, changing jobs four times in the next 5 years, each time for higher compensation. The rapid growth of computer and computer services firms helped define the “go-go years” of the late 1960s—a period of seemingly endless opportunity [19]. Johnson knew that her skills were in demand and did not worry about job security, working for several start-up services firms because the work was exciting and paid more, and believing there would always be other programmer jobs just around the corner.

In 1969 she joined Comm-Sci, a small computer services company consisting of the founder Bill Adair, programmer Tom Mosely, and a few contractors. They had developed a payroll system on a contract and were looking to market the program to other customers. Johnson was brought in to work with a customer to develop an accounts payable system. She had taken a number of extension accounting courses at University of California–Berkeley and, thus, was in a good position to understand not only the programming but also the customer needs with such a system.

According to Johnson, Adair was a charismatic leader but lacked follow-through on business details. Sometimes customers were provided services and not invoiced. More commonly, interested potential customers never received follow-up attention. Frequently, resources were purchased without any type of budgeting process. Mosely was a highly gifted programmer who wrote concise, elegant COBOL code for tax and accounting programs. The simplicity of the code made it easy for customers to add to and modify elements. Johnson learned much about programming from Mosely.

In 1971, Adair called Mosely and Johnson, still the only two employees, into his office and told them that he had some personal problems to deal with, that he was shutting the business down, leaving town, and that they would have to find new jobs. That night Johnson thought about the business and saw real value to the new concept of software products. She went back to Adair and offered to buy the rights (for a small royalty on future sales for 2 years) to the two systems—payroll and accounts payable. He agreed to her offer, as he had no plans for the software; and Johnson became an entrepreneur in the software products industry. Johnson named the firm Argonaut Information Systems, after Argonaut Pawn Shop, which she passed by on her way to work each day—choosing the name, in part, to appear near the front of a section of the telephone directory (Fig. 11.1).

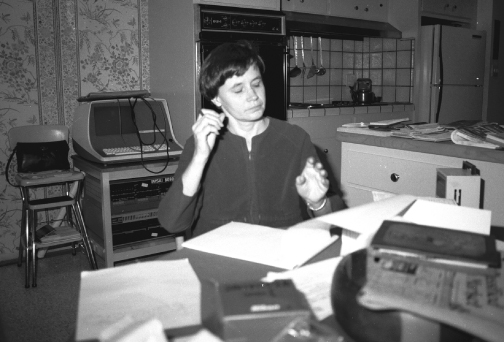

Figure 11.1. Argonaut Information Systems’ Chair Luanne Johnson.

(Courtesy of Luanne Johnson, 1986.)

Looking back, Johnson said it all happened too quickly for her to be scared. She rapidly put the finishing touches on the accounts payable system and began selling that and the payroll system. She was aware that software products were growing rapidly from Larry Welke, who traveled the country to learn of software products to add to his International Computer Products (ICP) Software Directory—an influential publication that helped the software products industry take off by listing many of the software products available nationally and internationally. In its first half-decade, many Fortune 1000 companies subscribed to Welke’s ICP Software Directory (launched in 1967) to learn of new products to purchase for their data processing departments, while software companies subscribed to better understand the competitive landscape [20]. (The quarterly directory started with free listings to gain broad participation and sold annual subscriptions for $25. It took off in 1968 after Kiplinger Washington Letter ran a short piece encouraging firms to buy software “rather than re-inventing the wheel.” For many years it was the standard source to learn about available software products.)

In the applications services trade, Johnson believed the industry was shifting. Applications services businesses were trying as never before to reuse as much code as possible. However, most customers continued to require substantial help with installation, customization, and training. This was gradually beginning to diminish as “code … [became] … more flexible and robust and had more options.” Johnson’s goal was to quickly get her products’ code in such good shape that they could sell as close to “off the shelf” as possible. She also felt major progress could be made by writing better documentation, to obviate the need for training. These were her early priorities with the firm, along with selling aggressively and creating a stronger organization. She made some sales just by following up with potential customers initially contacted by Adair. Other than the ICP Directory, little marketing was necessary to build the business.

One benefit Johnson believed she would have in owning a company was greater flexibility and the opportunity to work less than full time. She was remarried at this point, running a household, and raising her daughter. While there may have been a bit more flexibility, she ended up working long hours. Johnson ran this one-person business out of a room in her house for the first year, using three or four independent contractors off and on to assist with installations. The business was extremely low overhead; and there was no need for start-up capital. Thanks to the ICP Directory, sales were national from the start—her first customer was in St. Louis. In its first year Argonaut Information Systems had roughly $60,000 in gross revenue. The business began to grow and, by the second year, Johnson hired an administrative assistant. With this, she moved the operation out of her home and opened a small office. Within several years she hired programmers and had a staff of four or five. On several occasions when customers were late with payments, she would have to borrow money to make payroll. No bank would lend her money, so she borrowed funds from her father.

As the software products industry took off in the mid- to late 1970s, large firms such as Management Science America (MSA) began launching major marketing campaigns for their products. (Management Science America and Informatics, Inc., were the largest U.S. software products firms in the late 1970s. By then, both had software products revenues exceeding $30 million annually. The industry overall was composed of a handful of large firms and many small ones. In 1979 there were an estimated 1095 software products companies, with average annual revenue of just over $1 million [21].) Such large software firms, however, were targeting their marketing and sales to Fortune 500 customers. While these firms sometimes offered the same product features as Argonaut Information Systems, Johnson successfully focused on mid-sized and smaller firms and organizations. Much of her business came from companies that had installed IBM equipment. Soon they realized they had uneven demand and that valuable computing resources were often idle. They decided to capitalize on this by purchasing software from Argonaut to run some of their back office accounting functions in-house.

In the Bay Area there was an unusually well-developed base of independent contractors (ICs), which sometimes provided substantial competition. At times ICs, with even less overhead, would come in and do customized software for less than Argonaut charged for its products. Argonaut, however, was selling well nationally so that losing some local business was not a big problem. In general, Argonaut did particularly well in towns that did not have a major airport—places where none of the large software products and services companies would regularly fly in to make sales calls.

In its first decade Argonaut’s marketing was primarily limited to the ICP Software Directory (listings were free) and smaller ICP publications that emerged (that charged a modest fee). Argonaut did a bit of advertising in large trade publications like Computerworld, but generally Johnson believed that ICP was sufficient. Looking back, she believed it was the only marketing that paid off. Argonaut did not participate in trade shows. Johnson estimates that at least 90% of her customers originally learned about Argonaut from the ICP publications. This provided plenty of business to keep her small staff and contractors busy.

On Larry Welke’s (ICP) advice, Johnson attended her first ADAPSO conference in 1973 in San Diego and joined the association. ADAPSO had been launched in 1961 as a service bureau trade association. It soon became the leading trade association for computer services firms broadly and, by 1972, had also become the leading trade organization for the newly emerged software products trade. ADAPSO members were extremely open and shared information on successes and failures. Johnson later reflected, “I got my MBA from ADAPSO. It was an amazing environment to go in there. People from competitive companies would sit on panels and say, ‘Well, here’s the mistake I made. … here’s what to look out for.’ ” In the long run, ADAPSO proved of greater interest to her than Argonaut.

Johnson might have had an opportunity to greatly expand her firm, but this is not what she wanted. In the early 1980s the firm had grown to roughly 15 employees. By this time it was generating millions of dollars of revenue each year. Johnson hired a marketing guru with a master’s degree from Harvard to help with the business. Increasingly, she felt pressure from her employees to grow the firm. They wanted a larger organization with more layers of management, a firm where there would be opportunities for advancement and promotion. Johnson’s interest had always been in developing robust products, with excellent documentation, that could sell virtually off the shelf. She had succeeded in this. Given that her employees wanted something different from the business, she decided it was time to exit and sold her firm, although she served as a consultant off and on with the enterprise for a half dozen years. She also remained active in ADAPSO and would go on to become the president of this organization (discussed in trade association section).

GENTRY, INC.

Like Luanne Johnson, Grace Marie Hill was born in 1938. She grew up in Dallas and in Gilmer, Texas. A strong student at Hockaday Preparatory School in Dallas, she earned a scholarship to Harvard (Radcliffe) University. She majored in social relations with the goal of completing her undergraduate degree, going on for a doctorate, and becoming a professor. Following her first year at Harvard, she married Richard Gentry, who had just graduated from Texas A&M. Within a year they had their first child. Determined to pursue a career (and with strong support from Richard), she continued to take classes at the University of Arizona and University of California–Berkeley as the family moved first for Richard Gentry’s Air Force pilot training and, later, for him to start graduate school in physics at Berkeley in 1960. (This section, unless otherwise noted, is from the Grace Gentry Oral History [22].)

Richard Gentry, who soon decided he wanted to enter the workforce rather than continue in graduate school, joined IBM’s San Francisco branch as a systems engineer. He trained IBM customers in programming at the IBM Education Center for 4 years before transferring to the Government, Education and Medical Division (GEM). At GEM, he worked on data processing systems for Alameda County and soon distinguished himself by developing on his own time what came to be known as the Gentry Monitor, a highly efficient transaction processing system [23]. This system was the basis for IBM’s successful Filing and Source Data Entry Techniques for Easier Retrieval, or FASTER [23].

Meanwhile, Grace Gentry had become disillusioned with sociology at Berkeley and decided to pursue an academic career in statistics. Richard, knowing the future of statistics would be computer-based, suggested Grace gain computer experience and brought home a copy of IBM’s Programming Aptitude Test, on which she excelled. He also got her into a 2-week customer training programming course at the IBM Education Center.

Knowing the government was one of the best places, especially for women, to get advanced programming training, Grace Gentry took federal and local government exams. Scoring and interviewing well, she was offered positions with a dozen federal departments in 1967. She took an overload of classes to complete her degree in a semester and took a Management Intern position with the Social Security Administration (SSA). After advancing in the SSA but not wanting to move to Baltimore, Maryland, Grace Gentry was contacted by the University of California (UC) Statewide Electronic Data Processing Center and hired as a business analyst. Business analysts interviewed users to determine their needs and translate them to systems analysts, who in turn oversaw the programmers. With certain projects and deadlines, Grace Gentry worked as a systems analyst or did programming, teaching herself to use various programming languages. This led her to later jokingly reflect that she went backwards—from business analyst to systems analyst to programmer—but this broad experience would prove invaluable in later running an IT services contracting firm.

One day at UC Statewide, after Grace had developed a successful report writer for the university’s admissions departments, her boss’s boss congratulated her. She asked him how he heard about it, to which he replied, from a discussion in the men’s room. Grace Gentry responded, “Well see, that’s one of the problems. You guys go in there and piss together, and you chat and yak. How are we women ever supposed to be successful when we can’t go in there with you?” This got around and another male employee soon said, “Hey, Grace, would you step into the men’s room? I have something to tell you.” While it was a joke enjoyed by all, the fact that communications and decisions often occur in male-gendered spaces (whether the men’s room, boardroom, golf course, private club, or sporting events) at corporations and organizations was (and still is) quite real and can impact women’s opportunities to succeed and advance.

At the start of the 1970s, Richard Gentry left IBM to work for William Millard’s Systems Dynamics (SYSDYN). Millard, who had been head of Data Processing for Alameda County when Richard Gentry had done work for the county through IBM, later became famous for founding personal computer pioneering firm IMS Associates (IMSAI—in 1975) and fathering the field of personal computer retailing by co-founding ComputerLand (1976) [24]. His first venture, SYSDYN, however, failed in 1972. Soon after, a contact at Alameda County offered Richard Gentry consulting work, but for the county to hire him, he had to incorporate. This led to the formation of Richard E. Gentry, Inc., initially a one-person operation.

Projects grew with Alameda County; and Richard Gentry was asked to provide additional contractors. Grace Gentry had by that time moved from UC Statewide to Bank of America—as it began to actively recruit women for management positions. A manager at Bank of America told her that the bank felt it had missed out on hiring the best minorities and did not want to make the same mistake with women.

Although Grace Gentry saw opportunities at Bank of America, she left to help Richard with the Alameda County contract. Her experience at UC Statewide had left her with numerous women friends who had strong technical skills and experience. Within a year Grace and Richard Gentry had hired five women as independent contractors. While the company name was Richard E. Gentry, Inc., some called them “Wonder Women, Inc.” Later, the name was officially changed to Gentry, Inc.

Within a couple years, as the number of contractors working at the firm expanded, Grace Gentry stopped working on contracts and devoted full-time hours to running the business. Richard Gentry worked for the firm as a lead consultant. While he would have preferred it just be the two of them working as contractors, he went along with Grace’s decision to expand and run the enterprise. In the mid-1970s she had no models to offer guidance. If there were other brokerages hiring ICs for programming and system analysis, she did not know of any.

The initial hires were all women, which not only highlights the importance of personal networking, but also the risks involved in independent contracting—particularly in the early years when it was an uncharted business model. The firm only hired programmers and analysts with years of experience. Grace Gentry reasoned that men would not want the uncertainty of this type of arrangement—even if it paid more in the short run. What would happen when the contract they were working on ran out? Would there be others? Wouldn’t any potential advantage from a higher hourly rate be eaten away with health insurance and other costs? What was the path to career advancement? For married women the proposition was often seen quite differently: the family health insurance was commonly covered by their husbands’ jobs. To earn a higher wage and have flexibility to enter and exit the workforce was a real advantage. There could also be tax advantages to operating as a self-employed business.

The firm had virtually no overhead. Grace Gentry ran it out of her kitchen for more than a half decade prior to leasing and later buying an office building in Oakland (see Fig. 11.2). The Gentrys’ son, who was in high school, did the payroll. His younger sister took on this duty after he left for college. For analyst/programmers, the firm originally charged $12 per hour to clients. They paid $10 per hour to the contractors and did payroll only after collecting from clients. (This translated to $20,000 a year gross. A substantial salary for an experienced programmer at the time was around $10,000 to $14,000 a year. The first year the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics added the occupation of programmer was 1984. The midlevel salary for a programmer at that time was $27,158—or $12,867 adjusted back to 1974 (programmer salaries likely grew more than inflation) [25].) Thus, there was a delay in getting paid—a factor that mattered far less when it was secondary rather than primary income.

Figure 11.2. Grace Gentry at her home office (kitchen table) at Gentry, Inc. (1974–1977).

(Courtesy of Grace Gentry.)

Gentry, Inc.’s rates to clients were a fraction of what clients had to pay IBM, Lambda, or other large services consultant enterprises for similar talent. Occasionally, potential clients wanted to check out the facilities—“kick the tires” as Grace Gentry put it. She would just confidently explain to them it was run from their home and that is why they were able to supply such talent at a rate sometimes only about one-third of what the giants would charge. Grace Gentry intentionally focused on serving smaller and mid-sized companies and organizations that were more price sensitive and often only needed one to several people (business the large firms generally avoided). The IT services giants, having to pay their salaried employees on the sidelines when projects ended and having other large overhead expenses, could not approach Gentry, Inc.’s rates for talented experienced programmers and systems analysts.

Within several years, one of Grace Gentry’s contractors mentioned that her husband, an ex-IBM employee working for a smaller company, was not happy with his current situation and might want to work for Gentry, Inc. After he signed on, many other men soon followed—recognizing the advantage of getting paid for all the hours they actually worked, earning higher income, and betting on themselves and their skills to find the next job if necessary. Some younger, single male contractors went without buying health insurance, maximizing their net income.

Much like the uncertain professional status for programmers, which had contributed to its being at least marginally more open to women than many professions in the first decade (mid-1950s to mid-1960s) of the computer industry, the financial risks and uncertain status of IC programmers and systems analysts had facilitated women’s entry into the field in this industry segment’s first decade—the 1970s. By the 1980s, the model was more established; and there were numerous IC computer services brokerages emerging in urban areas throughout the United States. Many of these businesses were quite small, while a minority, including Gentry, Inc., grew to be mid-size enterprises with more than 100 contractors. The mix shifted toward male independent contractors and probably was roughly the same as the broader IT services industry. Grace Gentry’s hiring all women in the first years was the result of her network of skilled contacts. It was about hiring highly competent contractors she could trust to excel for their clients. While the pool of candidates may have favored women in the early years (with men questioning the stability and status of IC jobs), this soon changed. Throughout, Grace Gentry hired the best candidates she knew or could recruit for the job regardless of gender.

Grace Gentry also took major steps to make independent contracting a career and not just a short-term job. Her contractors often worked with the firm for many years. Growing up, she had done various door-to-door selling jobs and was skillful at obtaining contracts from new clients. Early on, all the contracts they had were with Alameda County. She quickly saw the risk that this posed to her firm and her contractors. She aggressively sold her company’s services in the public and private sectors, and diversified her base of industry clients. This enabled the firm to weather multiple recessions and maintain work for her contractors.

Grace Gentry also took the initiative to help her contractors extend their skills and make career advances similar to those they might make as employees at a larger firm. She would let programmers working on a project advance to systems analysts (charging the lower programmer rates) as they learned new responsibilities on the job. This helped the client save money, and helped the contractor retool upward, and in the long run also helped Gentry, Inc. With the next job she would be able to hire them out as systems analysts, charge the higher rates, and offer them the higher compensation. She learned that contractors were far more loyal if they had opportunities to advance their status and compensation.

In the late 1970s Grace Gentry sought to further diversify her company by adding new businesses, including a software products division and a third-party products division. With the latter, Gentry, Inc. supplied Hewlett-Packard equipment and sold software and services to create complete turnkey systems to meet clients’ needs. Like many traditional services companies (that had employees rather than ICs), Gentry, Inc. sought to exploit the economies of reusing code by moving into software products. With these divisions, Gentry, Inc. hired technicians (programmers, analysts, project managers) as employees for the first time. (Gentry, Inc. already had some salaried sales and office staff.)

In 1979 Gentry, Inc. created a report writer called REX and followed this with a similar, more advanced, product the following year called PAL—both for the HP 3000 minicomputer. Gentry, Inc. was diligent at conducting customer surveys and updating the product. Grace reflected that it was rewarding to be a technical leader, but also somewhat frustrating, as competitors would see the new upgrades to Gentry’s products at an annual trade show and add all the same features to their products.

As personal computer sales increased during the 1980s, it hurt HP’s minicomputing business and the sales of Gentry, Inc.’s software products and turnkey solutions. When Grace Gentry suggested that her developers create report writers for PCs, they discouraged her from pursuing this, telling her, “We’re going to do you a great favor … [and] … look for other jobs because you shouldn’t do this. You cannot win against Microsoft.” By that time the original contracting services division was clearly supporting the software products division, and the latter was sold off without profit. The turnkey business, also dependent on the success of HP minicomputers, quickly succumbed to a similar fate. While the products and turnkey businesses had helped support the contracting business at times, by the mid-1980s contracting was supporting the other two. (Although the independent contractor model allowed brokerages such as Gentry, Inc. to quickly downsize if contract work diminished, Grace Gentry always worked harder than ever to sell to businesses and organizations during such times and keep all the skilled contractors employed. She believed keeping the talent was of fundamental importance to the long-term success of the business.)

In 1986 Senator Patrick Moynihan introduced legislation—Section 1706 of the 1986 U.S. Federal Tax bill—that forever changed the landscape of the IT contracting industry. This section required that “technical service firms” that supply ICs to clients would no longer be granted employment tax-safe havens that apply to all other types of businesses using ICs. It, in effect, outlawed the IT independent contractor brokerage business model of Gentry, Inc. and similar firms. The bill was politically motivated and long fought for by trade organizations representing large IT services businesses that only used salaried employees [26]. To mobilize to try to fight this legislation, a number of IT services independent contractor brokerages, including Gentry, Inc., launched the trade association, the National Association of Computer Consultant Businesses [26]. (A fuller discussion of the NACCB is in the section on trade organizations in the latter portion of this chapter.)

Several years after Section 1706 hit the books, Gentry, Inc. switched to an employee-based model to avoid escalating historic tax liabilities in case the firm was ever found in violation of the code. The Gentrys’ equity stake in their Berkeley home provided the payroll cash that allowed them to convert [26]. The legislation led some computer services brokerage businesses to shut down. The NACCB had a legal defense fund to protect firms that continued with a contracting model or had potential back taxes prior to converting to the employee model. By 1995 there were more than 125 member companies in the NACCB. Most were one-branch operations that served a single urban/regional (75-mile radius) market. About a quarter had annual revenue under $3 million, another quarter between $3 and $7 million. Approximately 15% had annual revenue exceeding $20 million [27].

The number of employees at Gentry, Inc. hit an all time high of around 200 in the middle to late 1990s as Y2K fears skyrocketed. In July 1998 Grace and Richard Gentry decided to retire and sold the firm to Personnel Group of America (PGA) for $12.5 million in PGA stock [28]. Many of their contractors/employees were longtime friends who knew that both Grace Gentry and Richard Gentry had taken no salary during rough economic times in the past (the recessions of the early 1980s and early 1990s) to keep them employed. These friends were thankful that the Gentrys sold, as they believed this pioneering firm would have gone under trying to keep everyone employed when the greatest challenge to date soon hit the IT industry, the so-called dot.com collapse.

PHYLISS MURPHY AND ASSOCIATES

Phyllis Murphy was born in 1939 and grew up in Quincy, Illinois. She graduated with a degree in accounting from Western Illinois University. Upon completion of her degree she applied to numerous accounting firms in Chicago, and eventually was hired by a small company on Chicago’s west side. A year and a half later she took a position in accounting with real estate management firm Draper and Kramer. In 1966 she was asked if she wanted to learn to program. When she inquired what this was, she was told computers “will do exactly what you tell them to do.” She remembered thinking, “this could be love.” She took a four and a half day programming course at Univac and then began wiring panels on a Univac 1004. She soon became Draper and Kramer’s Director of IT. She recalled that at the professional meetings she attended for IT managers, she was often the only woman. (This section, unless otherwise noted, is from the Phyliss Murphy Oral History [29].)

Murphy left the firm in 1972 to gain expertise in data bases and networked computer systems—working for a service bureau firm for two and a half years. In 1974 she joined Consumer Systems, an IT services consultancy with major offices in Chicago and Minneapolis. She started as a consultant but soon began to manage IT projects for large clients, including a project to move insurance giant Banker Life and Casualty from a pure manual system to an online COBOL system. By 1978 Murphy was leading a group of 145 consultants for Consumer Systems. That year her husband had an opportunity to advance his career in Southern California; and they moved to Los Angeles. Phyliss Murphy agreed to head the much smaller Los Angeles office. She was the only woman to head an office for Consumer Systems.

Murphy found the Los Angeles operation and IT services environment to be far different from the Midwest. The sales personnel were largely ineffective and had no corporate training—unlike sales staff for Consumer Systems in Chicago and Minneapolis who were all trained at the Chicago headquarters. There were more IC consultants, and long-term relationships between IT service firms and client organizations were less typical in Southern California. Meanwhile, Consumer Systems was diversifying into a range of unrelated businesses and not adequately funding the Los Angeles office.

Given this situation, Murphy left Consumer Systems in 1981. She was very selective in seeking out a new employer. She briefly joined a permanent placement firm to help them hire staff to train IT specialists and to better learn the IT services terrain of Los Angeles. Having investigated many firms, and seeing problems (poor sales infrastructure, bad financial management, disrespectfulness, or poor back office) at each, she decided to start her own IT services business.

In 1981 Murphy launched her company. In a business where reputation and trust are critical, she wanted to ensure that clients could easily identify her with the firm and named it Phyliss Murphy and Associates. She used roughly 60% salaried employees and 40% ICs—feeling a mix worked well in Southern California (Consumer Systems had only salaried employees). She had gained experience working with large clients in the past, and she sought and received business from both large and small companies/organizations.

While understanding and responding to regional differences in establishing her business (such as using 40% ICs), she believed she managed her business in a Midwestern manner—focusing on honesty, integrity, and fiscal conservatism—that set her firm apart from many in the area. For more than a year she ran the business from her home, conducting interviews at a local Denny’s restaurant.

By the third year Murphy had more than 20 employees/contractors and had tried out four salesmen—two who worked out—and had moved to lease office space. She always felt that quality sales staff was the greatest challenge in the computer services business. While she did not enjoy making sales calls, she did it regularly to close contracts. (With anticipated gridlock on the freeways during the 1984 Summer Olympics, Murphy shifted temporarily to have her sales staff primarily work the phones rather than make in-person sales calls. This experiment proved highly successful and ever since she has had her sales staff focus on calls, setting up face-to-face meetings when clients request it.) With her accounting background, she managed all the finances and accounting herself. Early on, she secured major contracts with large enterprises such as US Borax, which set up opportunities with many others. In contrast with Johnson’s firm and Gentry’s firm, Phyliss Murphy tried to target larger businesses, believing they were more professional and reliable than smaller enterprises in the greater Los Angeles area and that larger firms (generally far more than $500 million in revenue annually) understood supplemental technical staffing and were more focused on successfully completed IT projects than monitoring every minute of consultants’ time.

Starting her business in the 1980s, the independent contractor model was already well established. Often both male and female services consultants preferred this model; it could lead to more compensation, it allowed them to manage their own money, and it resulted in the pride and independence of self-employment. Her employees and ICs generally had 6 years industry experience for the more junior positions and 8 to 10 years or more for senior employees/contractors. From the beginning, her business was roughly composed of 20% women and 80% men and had substantial ethnic/racial diversity. In the early years, Murphy believed that her being a woman helped, because she stood out; but in time it was neither a disadvantage nor an advantage—she believed the success of the business rested on delivering strongly for clients.

Oftentimes larger computer services businesses that were concentrated in other regions would seek to enter or expand in the Los Angeles market through acquiring local small to mid-sized computer services providers. Murphy related that these big firms often did not understand the Los Angeles environment in services (investing in expensive marketing campaigns, etc.) and frequently their newly created Los Angeles business/branch office would shut down within a few years. This occurred with acquisitions by Boca Raton-based Compustaff, and some other large services providers, and kept the environment favorable for small to mid-sized businesses such as Phyliss Murphy & Associates.

In 1987 Murphy became very actively involved with the NACCB. She started a chain letter outlining the history behind and the injustice of Section 1706. As a result, she became among the most high-profile critics of the legislation and was quoted in the Wall Street Journal and other publications. Taking on this role, she knew she had to switch to an all-employee only model right away—fearing IRS audits, of which four came in rapid succession.

Of all she gave to aid the efforts of the NACCB, she felt she received even more. As a result of the NACCB, she wrote conversion fees into every contract, purchased group insurance, and learned much that contributed to her firm’s bottom line. Murphy successfully navigated her business through the extremely tough period from 2000 to 2002 and continues to own and run this successful enterprise. In reflecting upon her 28 years leading the business, she emphasized that the industry has been “great … for women,” and she has no plans to retire.

ADAPSO AND NACCB

Given the opportunity to demonstrate their many skills to colleagues and competitors, these women entrepreneurs (Luanne Johnson, Grace Gentry, and Phyliss Murphy) all became leaders in trade organizations. Here, they perhaps had greater understanding and ability than male leaders to help facilitate environments of trust, ethical practices, and sharing of information—the cooperation critical for such associations to add value by taking advantage of the collective wisdom of members and coordinating a united front to battle outside threats from competing industry segments and unsupportive legislators.

Luanne Johnson had been an active member of ADAPSO since 1973 and after she sold Argonaut Information Systems in 1980 (and stopped consulting for the enterprise in 1986), she accepted the invitation from this trade association to run the newly formed ADAPSO Foundation. ADAPSO had reached its 25th anniversary and formed the foundation as a way for the industry and organization to give back to the community. Under Johnson’s leadership the foundation focused on various initiatives to help disadvantaged and disabled children.

Over the years Johnson had gained the respect of John Imlay, President of Dun & Bradstreet Software Services, Larry Welke (ICP), and other powerful individuals within ADAPSO. Following her short and successful stint heading the foundation, Johnson was asked to be executive director of ADAPSO in the late 1980s. ADAPSO by that time had grown into a massive trade association with hundreds of member firms—including nearly all the large players in software and services. It was a multidivisional association—with divisions for Information Systems Integration, Information Technology Services, Networked-Based Services, Software, and Vertical Applications & Remarketers—each with its own board [30]. Johnson had a degree of trepidation, but with strong encouragement from Welke and Imlay, and feeling she would always wonder “what if” had she declined, she signed on and moved from the San Francisco Bay area, her home for decades, to Washington, DC [18].

In the late 1980s and the start of the 1990s Johnson worked with the board to develop and implement a long-term plan focused on enhancing attention to membership services through a new Membership Services Department, as well as to boosting the image of the organization and increasing membership levels, communication, and education. ADAPSO, a major lobbying organization by this time, sought to promote “greater fairness in competition and regulation”—but this was a challenging task given the diversity of the association and industry segments with competing interests [30].

The software products industry had grown tremendously. There was also pressure to change the association’s name—in large part because it reflected just the data processing services industry. In 1991 ADAPSO became the Information Technology Association of America (ITAA). That same year a woman became Chair of the Board for the first time, Judith Hamilton, and Johnson’s title was changed from Executive Director to President.

Johnson and Hamilton’s elevation to the top leadership of ADAPSO/ITAA represented a significant break with the past. Since the 1970s ADAPSO had some women members, many of whom were quite influential at the committee level. However, they tended to come from small companies and had difficulty moving up through the organization. Beginning in the 1970s, ADAPSO increasingly became an organization of mid-sized to very large companies, and its leadership generally was in the hands of certain leaders from these large firms—nearly all male. Judith Hamilton, in contrast, came from one of the accounting and services giants, Ernst & Young, and along with Johnson represented a new era of women’s participation in the top leadership of the association. Both worked to maintain and extend ADAPSO/ITAA’s role in sharing ideas through roundtables (where chief executives of noncompeting firms discussed policies, practices, and outcomes) and conferences, expanding international programs, and representing the organization’s interest in a unified way to the government. In 1995 Johnson retired from her position as president but continued to work on international issues within the World Information Technology and Services Alliance, an organization she helped create to promote international cooperation and exchange in the software and services fields.

NACCB was a much different organization than ADAPSO. It was significantly smaller, had far less funds, was launched a quarter century after ADAPSO, and represented a very specific industry segment: IT consulting services brokerages. It also had been born out of a single issue, fighting Section 1706 of the 1986 tax bill. Within a few years, however, it expanded its scope. Grace Gentry, who had helped to found the organization, was an early president of NACCB and pushed strongly on not only 1706, but also to enhance membership services and benefits. She was a strong proponent of industry roundtables for executives to learn from each other’s strategic and organizational successes and challenges. NACCB was ideally suited for roundtables since most member businesses were quite similar but operated in different geographies and thus were willing to share extensive information on their firms.

Phyliss Murphy had been the leader of one of the two predecessors of NACCB—the SC-SCBA (Southern California Software Contracting Businesses Association), a similar regional organization formed in the early 1980s that focused on industry challenges posed by state law. She, too, was a strong voice within the NACCB in the formative years. Both Gentry and Murphy were important forces in pushing for a NACCB standard “Code of Ethics,” and Gentry created an industry survey—a highly useful tool for members in defining strategies and practices.

There were a number of computer services consultant businesses, particularly outside the organization, that engaged in activities that injured the reputation of the industry—such as hiring away talent from their own client organizations, submitting contractor’s resumes for a job without first determining the contractor’s availability or interest in that job, and similar unprofessional practices. By the early 1990s NACCB had a Code of Ethics in place that member companies had to honor. A description of the code was provided to clients and potential clients. Potential clients were encouraged by NACCB member companies to make certain that competitors adhered to the code, even if they were not part of NACCB. This helped elevate the overall ethical practices of the entire computer services consulting industry.

In its first decade, most NACCB members were small to mid-sized companies, and there were a significant number of women involved. In the early 1990s another woman entrepreneur, Peggy Smith, became the first Executive Director of the NACCB. Smith had worked at one of the large computer services consulting businesses, Lambda Technologies, in the early 1980s. General Electric’s GEISCO timesharing business expanded into the consultant business at the start of the decade and acquired Lambda. In 1982 Smith transferred from Philadelphia to open GEISCO’s consulting office in Greensboro, North Carolina. She was dissatisfied with GEISCO’s lack of understanding of the consulting business and inadequate support for her operation and left to form her own company with two other individuals from the business. Having significant success but disagreeing on strategic direction with her partner in the late 1980s (the first partner had already exited), she sold out her share. She was an active NACCB member; and Grace Gentry recruited her to consult on growing NACCB membership in 1989. She went on to work on a number of issues and activities for the organization in the first half of the 1990s [31].

In 1995 she was officially hired as NACCB’s Executive Director and soon secured an office in Greensboro for the trade association. She was instrumental in organizing and helping program NACCB annual conferences and industry roundtables and working with the organization’s legal department led by Harvey Shulman, in Washington, DC (the home office later moved to Washington, DC). While most of the rotating presidents of the NACCB were men, Gentry, Murphy, and Smith had an enormous early impact on this small but rapidly growing and successful trade association. Smith was responsible for organizational practices that boosted the momentum of the NACCB’s growth. Currently, of the three, only Murphy is still active in the organization. The NACCB has continued to grow rapidly and now consists of not only smaller and mid-sized firms but many of the giants in the computer services field.

CONCLUSION

Women are distinctly absent from the existing historical literature on entrepreneurial leadership in the software and computer services industries [32]. Even trade journal literature and existing archival resources provide no real sense that women were any part of the dynamic risk-taking culture critical to the formation of new businesses and the thriving new trades in computer services and software. The dominant tendency in business history and entrepreneurial studies to focus only on large businesses, or on the small businesses that grew to become giants, contributes to the notion that IT firm creation was exclusively a male domain. Yet when small to mid-sized companies and lesser-known industry segments, such as the brokerage side of the computer services consulting business, are examined, it becomes clear that women entrepreneurs contributed substantially.

Women such as Grace Gentry, Phyllis Murphy, Luanne Johnson, and Peggy Smith all had worked within IT departments or divisions of mid-sized to large corporations and organizations and, to varying degrees, saw limitations in advancement to leadership roles or met with inadequate funding and lack of respect. Each of these women demonstrated vision, courage, and a mixture of self-reliance and cooperative leadership styles to launch and grow new computer services and software products businesses between the 1960s and 1980s.

While at times these women faced higher hurdles—for instance, Luanne Johnson could not get any kind of credit line early on, and Peggy Smith after getting remarried was asked to have her husband co-sign for her existing line despite his having no role in the business (something that definitely would not have occurred in reverse)—they all persevered and had considerable success. In interviewing these women, they all stressed that the IT world, with the exception of large firms, focused on achievement and results rather than gender in hiring contractors or buying software products. Because there were fewer women than men in the IT business, especially in the early years, their skills and demonstrated results stood out and helped them secure and retain clients and customers. In the words of Phyliss Murphy, her ability to deliver results and her gender “stood out.”

Like small enterprise, trade associations, and especially leadership within these organizations, has been vastly understudied [33]. (Few historians have followed business historian Louis Galambos’s strong lead in doing rigorous analysis of trade association—as he did for the cotton textile trade.) All four of these women provided substantial leadership to trade associations, adding value to member companies. Johnson and Smith held ongoing top executive posts within ADAPSO/ITAA and the NACCB, respectively. Gentry and Murphy helped found the NACCB and SC-SCBA, and both contributed mightily to the NACCB for many years—Gentry serving as an early president, and Murphy actively involved to this day.

Much as women computer scientists are important as role models to women students in colleges and universities, the histories of women IT entrepreneurs can serve as models for future women founders and leaders of IT businesses. This chapter, which first outlined some of the barriers to women’s climb up the ladder in large computer and software businesses and organizations, highlights the important early role of entrepreneurial women in fundamental segments of the IT industry (computer services consulting and software products) and its leading trade associations between the 1960s and the mid-1990s. While these women’s achievements were not made without overcoming obstacles, their technical and leadership skills came to the fore, were highly valued, and tended to bring opportunities and reward rather than discrimination and rejection. Most of all, this study is intended as a small first step to recovering the early role of women IT entrepreneurs, and a reminder of the importance of preserving records of these developments before they are forever lost.

REFERENCES

1. “Lucent’s Initial Offering Nets $3.025 Billion,” New York Times (4 April 1996): D8.

2. Hewlett-Packard Corporation, Annual Report (2000). HP had a net income of nearly $3 billion in 1998.

3. eBay, Annual Report (2007).

4. “50 Most Powerful Women in Business,” CNN/Fortune; available at money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/mostpowerfulwomen/ 2008/index.html (accessed 12 December 2008).

5. See Nancy M. Carter, Colette Henry, Barra Ó Cinnéide, and Kate Johnston, eds., Female Entrepreneurship (London: Routledge, 2007); Jeanne Halladay Coughlin and Andrew R. Thomas, The Rise of Women Entrepreneurs (Westport, CT: Quorum Books, 2002); Robyn Eversole, “Change Makers? Women’s Microenterprises in a Bolivian City,” Gender, Work & Organization, Vol. 11, No. 2 (March 2004): 123–142.

6. Chandler’s primary books defining his focus on the “managerial revolution” and the emergence and growth of large vertically integrated firms are The Visible Hand (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 1977); and Scale and Scope (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 1990).

7. For shifts to go beyond Chandler’s focus on large vertically integrated firms, see Naomi R. Lamoreaux, Daniel G. Raff, and Peter Temin, “Beyond Markets and Hierarchies: Toward a Synthesis of American Business History,” American Historical Review, Vol. 108, No. 2 (April 2003): 404–433.

8. Of the many quality works, two early standouts are: Alice Kessler-Harris, Out to Work (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981); and Thomas Dublin, Women at Work (New York: Columbia University Press, 1979).

9. There have been many quality historical studies of women’s leadership in philanthropic and benevolent societies, politics, science, and medicine. For example, Louise W. Knight, Citizen (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006); Elisabeth Griffith, In Her Own Right (New York: Oxford University Press, 1984); and Evelyn Fox Keller, A Feeling for the Organism (San Francisco: W. H. Freeman, 1983). Histories of women and business entrepreneurship are rare and tend to be on the 19th century or first half of the 20th century (prior to the advent of the computer industry). See Wendy Gambler, “A Gendered Enterprise: Placing Nineteenth-Century Businesswomen in History,” Business History Review, Vol. 72 (Summer 1998): 188–218; Susan M. Yohn, “Crippled Capitalists: The Inscription of Economic Dependence and the Challenge of Female Entrepreneurship in Nineteenth-Century America,” Feminist Economics, Vol. 12, No. 1–2 (January/April 2006): 85–109; Kathy Peiss, “ ‘Vital Industry’ and Women’s Ventures: Conceptualizing Gender in Twentieth Century,” Business History Review, Vol. 72 (Summer 1998): 219–241.

10. Joan M. Greenbaum, In the Name of Efficiency (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1979).

11. Occupation status varied between firms. For the battles for authority and status in corporations’ early computer centers see Thomas Haigh, “The Chromium-Plated Tabulator: Institutionalizing an Electronic Revolution, 1954–1958,” IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, Vol. 23, No. 4 (October– December 2001): 75–104.

12. Martin Goetz Oral History, conducted by Jeffrey R. Yost (3 May 2002), Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota; available at www.cbi.umn.edu/oh/.

13. John Cullinane Oral History, conducted by Jeffrey R. Yost (29 July 2003), Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota; available at www.cbi.umn.edu/oh/.

14. Jack Stone, “The Human Connection” Computerworld (4 July 1977): 17.

15. Katharine M. Donato and Patricia A. Roos, “Gender and Earnings Inequality Among Computer Specialists,” in Barbara Drygulski Wright ed., Women, Work, and Technology: Transformations (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1987), pp. 291–317.

16. Katharine M. Donato, “Programming for Change? The Growing Demand for Women System Analysts,” in Barbara F. Reskin and Patricia A. Roos, Job Queues, Gender Queues (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1990), pp. 167–182.

17. Myra H. Strober and Carolyn L. Arnold, “Integrated Circuits/Segregated Labor: Women in Computer Related Occupations in High-Tech Industries,” in Heidi I. Hartmann, Robert E. Kraut, and Louise A. Tilly, eds., Computer Chips and Paper Clips (Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1987), pp. 136–182.

18. Luanne Johnson Oral History, conducted by Jeffrey R. Yost (12 August 2008), Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota; available at www.cbi.umn.edu/oh/.

19. The meteoric rise and subsequent fall of the stock of H. Ross Perot’s Electronic Data Systems was a central tale of James Brooks’ The Go-Go Years (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 1974).

20. Lawrence Welke, “Founding the ICP Directories,” IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, Vol. 24, No. 1 (January–March 2002): 85–89.

21. Martin Campbell-Kelly, From Airline Reservations to Sonic the Hedgehog: A History of the Software Industry (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003), pp. 18–19, 127.

22. Grace Gentry Oral History, conducted by Jeffrey R. Yost (11 August 2008), Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota; available at www.cbi.umn.edu/oh/.

23. Richard Gentry Oral History, conducted by Burton Grad (24 May 2006), Computer History Museum; available at www.computerhistory.org/collections/oralhistories/.

24. Millard’s leadership of IMSAI and ComputerLand is chronicled in Paul Freiberger and Michael Swaine, Fire in the Valley, 2nd ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2000).

25. Carl Prieser, “Research Summaries: Occupational Salary Levels for White-Collar Workers, 1984,” Monthly Labor Review (1984): 43–45.

26. Harvey Shulman Oral History, conducted by Jeffrey R. Yost (30 March 2007), Computer History Museum; available at www.computerhistory.org/collections/oralhistories/.

27. 1995 NACCB Operating and Compensation Survey (copy provided to author by Grace Gentry).

28. Grace Gentry Oral History, conducted by Luanne Johnson (24 May 2006), Computer History Museum; available at www.computerhistory.org/collections/oralhistories/.

29. Phyliss Murphy Oral History, conducted by Jeffrey R. Yost (18 December 2009), Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota; available at www.cbi.umn.edu/oh/.

30. ADAPSO Annual Guide (1990), ADAPSO Records, Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota.

31. Peggy Noell Oval History, conducted by Jeffrey R. Yost (29 January 2009), Charles Babbage Institute, available at www.cbi.umn.edu/oh/.

32. Martin Campbell-Kelly, From Airline Reservations to Sonic the Hedgehog: A History of the Software Industry (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003). This is an excellent history of the software products business and the first decade of the services industry. Its cases are made up by the first business in the overall software and services industries and the players that grew to become large firms—these were all headed by men.

33. Louis Galambos, Competition and Cooperation (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1966).