Tim sits idly in his favorite café, looking repeatedly at his watch. He’s 15 minutes late. Don’t marketing guys have any concept of time, he thinks, half joking to himself. Finally he sees Randal’s BMW drive into the packed parking lot and pull into an empty handicap spot. Randal turns off the car and then casually places a temporary handicap placard on his rear view mirror and quickly strides into the cafe.

“Hi Randal, good to see you. I saw the handicap placard. Are you doing okay?” Tim asks, somewhat concerned and curious.

“Hi Tim. Thank you for asking. I’m doing alright. I thrashed my back last week playing tennis; couldn’t walk a damn. It expires next week. I figured I just might as well take advantage of it while I still can.”

Tim thought back to the last time he had worked with Randal. Tim had always been an altruistic spirit of the rules, try-and-make-a-better-system kind of guy, where Randal had been much more practical, making the most of the rules he was given. “I’m glad your back is doing better,” Tim replies. “So Randal, over the phone you said you wanted to learn a bit more about Critical Chain?”

“Correct Tim. I was hoping you could give me a high-level explanation and I wanted to see if it was something our engineering team could use. I did some checking and heard that they talked about Critical Chain, but I don’t think they got very far. I wanted to hear about your experience and if it was something that you found useful.”

Tim thinks to himself briefly. In the past, he tried to provide lots of project management details to someone who was more business focused. It only succeeded in confusing the person rather than helping them understand. Always best to start high level and then go into details as needed. “Sure Randal, I’ll walk you through a quick introduction. If you want more details, just let me know. Does that work for you?”

“Sure Tim, fire away.”

“Critical Chain is a Theory of Constraints solution

that addresses the common problems found in project management so we can better plan, manage, and be more successful with projects. Randal, are you familiar with traditional scheduling and Critical Path?”

“Just the basics, Tim. You build out an overall schedule by looking at defining all of the tasks and work involved and their inter-connections. Then you identify the Critical Path, which is the longest sequence of tasks needed to complete the project. From there, you focus your efforts on managing the Critical Path. I’ve seen Gary, the engineering manager, run a few schedule building sessions.”

“So one of the first steps in the Critical Chain is to be sure that your resources

are leveled.”

“Resource what?”

“Resource leveled. It is a function within the scheduling tool that makes sure that you do not schedule more than one task to a resource at a time. Think of it this way. If I asked you to go to one customer tradeshow the first week of June and I asked you to fly to Florida to support a customer demo the same week…”

“It would be impossible to do, Tim.”

“Exactly. So we resolve resource contention or level the work so we’re not asking resources to do more than one full time task at a time.”

“Sure, put that way, it sounds like a very good idea.”

“Second, Critical Chain is very focused on managing variability

—any time a task might finish later or sooner than expected. Simply put, if there were never any delays in schedules then project management would be a snap. Since there are always delays and we don’t know where or when, Critical Chain helps us manage this variability.”

“How?”

“So Critical Chain focuses on trying to reduce behaviors that cause delays and sets up buffers to absorb and manage delays. It also focuses less on individual deadlines and more on the overall deadline, also known as the project due date.”

“Tim, I know Gary gets all bent out of shape when resources are late and the project starts to run late. So is Critical Chain just setting up more milestones and is less focused on the tasks?”

“Not quite, Randal. Think of it this way. If every task was late but the project still delivered on time, the project would be a success. At the same time, if every task was on time, but the project was still late it would be not be a success.”

“True Tim, but not realistic.”

“But true in the sense that at the end of the day we care the most about the overall project deadline. So if the schedule was set up in a way that task delays could be absorbed by an overall buffer that protected the overall deadline—the thing we care about the most—this would be of value.”

“I guess, Tim. We definitely have issues hitting our overall deadlines. So anything to better protect them would be of value. I would have to think a bit more about this and more likely need to pull Gary in. So you said Critical Chain was part of the Theory of Constraints. Like a physics theory or something?”

“So the Theory of Constraints (TOC for short) is a general problem-solving model

that can be applied to a variety of environments, but it has one fundamental concept. In looking at any kind of system such as project management, manufacturing, or distribution, it implies that if you look in the right way and hard enough you will find that there is one thing, one constraint, that limits the overall system. So if you focus improvement efforts on this one area, the whole system will benefit and the bottom line of the organization will improve.”

“Hmm…Tim, like you said, it sounds a rather bit academic and theoretical. Is it really true?

“Well, let’s go back to Critical Chain. TOC looked at all of the common project management issues

, looked at how they were interconnected, and what were the root issues driving them. It then focused building a solution to address these issues. For example, one of the biggest issues with traditional schedules is that once you are late there is not an inherent system to recover. So that is why Critical Chain focuses so much on reducing variability (behaviors and level loading) and managing it (buffers). The better you can manage variability (one possible constraint) the more likely the overall project (system) will succeed.”

“So TOC was used to create Critical Chain?”

“Correct. And it can be used to help with the implementation of Critical Chain.”

“Hmm. Interesting thoughts Tim,” Randal turns to his coffee and takes a few sips. “So, that was a good text book background do you have something more real world you can share with me? So it’s a project management system. So what is the marketing pitch? Which customer pain points does it address? What are the benefits? What is the value? Give me some real-world examples.”

Critical Chain Issues, Benefits, and Sample Results

Tim pauses for a moment and collects his thoughts. “Sure Randal. So Critical Chain helps us address several common project management issues that happen in a variety of project management environments. Some of the most common ones are:

- Projects miss critical deadlines and market opportunities [crt 25]

- We cut too many key features to make deadlines [crt 19]

- Our products are not competitive enough (due to slow project turnaround, missing deadlines, and cutting key features) [crt 23]

- There is too much resource burn-out and turnover [crt 14]

- We go over budget due to project overruns and do not make expected revenues for our product lines [crt 26]

- There are internal projects that fight over shared resources [crt 18]

“That’s quite a list, Tim. Missing deadlines, cutting features, and being competitive all make sense to me. We would have to talk with Gary about resource burn-out and struggles. Give me some more time and I could work with Gary and probably come up with a few more items to expand your list.”

“True, these are the key issues. Depending on the organization, some of these issues will stand out more than others or be phrased slightly differently.”

“So, Tim, let me give you a marketing tip. It’s great that Critical Chain can help address all of those issues. The real question is if one of those issues is really critical and more significant than the others, then I am very likely to pay big bucks to fix it. In other words, what are the customer’s biggest pain points?”

“Okay…” feeling a bit odd to be lectured by Randal, “So Randal, from the list of issues I just went over, what really stands out to you?”

“Great question Tim! For us, hitting the major deadlines is the single most important factor. If we miss the deadlines, we delay our funding. Cutting features and resource burn-out are some factors. But far and beyond everything is about hitting the deadlines.”

“And Randal, what happens if you consistently miss schedules to the point that you continue to lose funding?”

“Well in that unlikely case it happens enough, it is likely the company could eventually run out of money and fold shortly thereafter [crt 28]. Which would be bad. But hey I’m a marketing consultant and missing schedules would be engineering’s fault.”

“And how well is engineering holding up meeting schedules?”

“They’re okay, but as the company is ramping up, so does the work, the deadlines, and the pressure. I guess, thinking more about it, the delays are likely to get worse and worse pretty soon.”

“And if the company folds soon, what happens to your MBA internship?” Tim asks, building on the discussion.

“My internship goes away. Oh crap! That means I would not be able to close out the internship requirement for my MBA and I could be held back at least a year!”

“And the company’s health and employees could be at risk too?” Tim inquires, trying to get Randal to think beyond just his own interests.

“Yeah, yeah, that too,” Randal says a bit disheartened.

“Okay, Randal, as you say, I think we have successfully found the company’s, as well as your personal, biggest pain point, and why we need to look at improving the company’s project management.”

“Yeah, I’ll say. I thought being in marketing and an intern, I was safe. I guess it’s a bit more complicated than I thought.”

“So we covered the common project management issues. Being a bit more hopeful, let us talk about some of the common Critical Chain benefits.

They include:

- On-time delivery of products significantly improves [frt 8]

- You are able to complete projects much faster [frt 8]

- Hidden or misused resource capacity is identified [frt 12]

- The company and its products are more competitive [frt 14]

- The company is more profitable [frt 20]”

“That seems like a reasonable list, Tim.

Taking a cue from Randal’s earlier comment, Tim asks, “So what benefits stand out to you the most, Randal?”

“Well Tim, as I said before, right now it’s critical to get reliable, consistent, on-time delivery. Not only is it important for the survivability of the company, but also for our long-term profitability.”

“So we have identified your key issue as well as the key benefit to focus on and help move the company forward with Critical Chain,” states Tim.

“Um, not quite Tim. The issues and benefits sound nice and all. But I have heard these same benefits time and time again claimed by other project management vendors and solutions. I need to know this is real. Show me proven results. And tell me without confusing me why this Critical Chain can really deliver these results. Then I might be a bit more motivated and convinced.”

“Okay, okay, Randal,” Tim concedes, a bit surprised at the push back. “Give me a bit more time and I can address all of your questions.”

“Wouldn’t want to make it too easy for you Tim,” Randal says with a friendly smile.

“Well Randal, you are in luck. I happen to have a few examples with me.” Tim then proceeds to pulls out a folder of printed documents. “So every company and circumstance is unique, but what you can see here are some of the exceptional results

that some companies have been able to achieve from a variety of different Critical Chain providers.”

Avraham Goldratt Institute (AGI )

Using their experience and Critical Chain, they have the following customer results (see

www.goldratt.com

) (2.3):

- Seagate brought the first 15,000 rpm disc to market ahead of competition, causing all competition to pull out of the market.

- Harris Semiconductor used Critical Chain to manage construction of its $250 million wafer fabrication plant, completing it in just 13 months where the historic average was 54 months.

- Lucent Technologies tripled its development project capacity (5 to 17), reduced its new product introduction interval by 50%, and completed 100% of their projects ahead of time.

Goldratt Marketing Group

www.toc-goldratt.com

has a TOC reference bank of results that includes (2.4):

- eIRCOM telecommunications improved due date performance from 40% to 90% and significantly reduced lead times.

Realization

Realization

lists several customer summaries, brief case studies, and customer videos at

http://www.realization.com

(2.6).

High Tech New Product Development. HP Digital Camera Group:

- Before: Six cameras launched in 2004. One camera launched in the spring window. One out of six cameras launched on time.

- After: 15 cameras launched in 2005, with 25% lower R&D expenses. Seven cameras launched in their spring window. All 15 cameras launched on time.

Aircraft Repair and Overhaul. US Air Force, Warner Robins Air Logistics Center, C17 Production Line:

- Before: Throughput of 178 hours per aircraft per day. Turnaround time 46-180 days. Mechanic output 3.6 hours per day.

- After: 25% increase in throughput. Turnaround time reduced to 37-121 days. Mechanic output increased to 4.75 hours per day. 40% overtime reduction.

ProChain

ProChain lists several customer success stories as well at

http://www.prochain.com

(2.7). Clients have experienced:

- 20-50% reduction in actual execution of projects

- 30-60% increase in productivity

- 50-200% increase in project throughput

- Return on investments ratio greater than 100:1

- Significant improvement in quality of life

- Stable and continuous process improvement

There is also an example of Habitat for Humanity using Critical Chain scheduling to set a new world record building a four bedroom house in 3 hours, 44 minutes, and 59 seconds. (2.8)

“So Tim, these are some very compelling results. Can I expect these same results in my organization?”

“That is a great question, Randal. It depends on your individual circumstances. In implementing Critical Chain, some organizations have found huge opportunities where they can significantly improve their operations. Other companies have found significant improvements, but not as dramatic as these. As we walk through better understanding Critical Chain as well as how your organization works, we can highlight the opportunities and potential impacts of implementing Critical Chain.”

“Okay, Tim, that makes sense. These results look promising. Individual results may vary. So tell me how can Critical Chain really deliver?”

Key Parts of Critical Chain

“So, as you asked Randal, how does Critical Chain get these results

? Some of the key parts include:

- Project buffers to better manage task variability [frt 1]

- Reducing bad multi-tasking to find hidden and misused resource capacity [frt 1]

- Setting goals and building schedules back to front [frt 1]

- Organizational analysis (TOC TP) to better understand the overall project environment (creating the CRT and FRT)

“Whoa, Tim, this is a little terminology heavy and some of these do not make sense to me. I’m just a simple marketing guy.” Randal says, raising his hands up and smiling. “Can you give me a high-level explanation of these and then we can possibly dig into them in more detail with Gary?”

“Sure, Randal.”

Project Buffers to Better Manage Variability

“So Randal, as I asked before, what is the key issue in project management?”

“Managing project risks effectively, hitting deadlines, staffing, managing scope, and building the right product all come to mind, Tim.”

“Those are all good Randal, but as I noted before, one key thing to look at is variability.”

“Sure Tim, I have some familiarity with variability. It is what Gary talks about all the time when his team misses a deadline. He talks about there being more work involved than originally expected, that additional scope and requirements were added, resources were not available, tasks took longer than expected, and worse project disasters happened that can totally sink a project.”

“True and when we originally build a schedule, how do they take into account this variability?”

“Well of course Gary does. Kinda… Well, maybe not exactly. He asks the engineers for their estimates, he ties everything together, and then we call it a schedule. Well, actually an initial estimate. Then management looks at the estimate and starts cutting out time. Then we end up with something that management feels is aggressive and somewhat realistic and something that engineering doesn’t scream too excessively about.”

“And how often do you meet these schedules, Randal?”

“The original schedule or the latest version of the revised schedule?”

“The original.” asks Tim.

“Well Tim, in general, not at all or at least never consistently. Engineering hits the typical unexpected and unplanned issues—they’re juggling multiple projects, complain about being stretched out and understaffed. They ask for more time; sometimes we replan and give them more time, and even then they’re likely to miss it. If we don’t give them more time, they’re likely to push out anyway or cut major features.”

“So Randal, does it look like this process is working for you in the long run?”

“Well… No, not really”

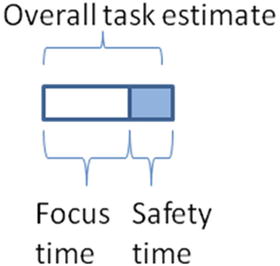

Tim draws the following diagram.

“So, Critical Chain sets up a formal system to better manage project variability. When an engineer estimates a task, there can be two sets of time.

Focused time

is the ideal time the task would take if the engineer just worked on that one task with no problems and no interruptions.

Safety time

is the padding the engineer adds to that focused time estimate to take into account possible issues, such as the other work they are doing, paranoia, etc. For Critical Chain, we build the schedule based on the focused time and aggregate the safety time from all tasks to create a project buffer at the end of the project [frt 1].”

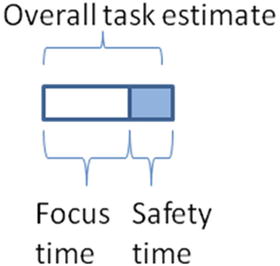

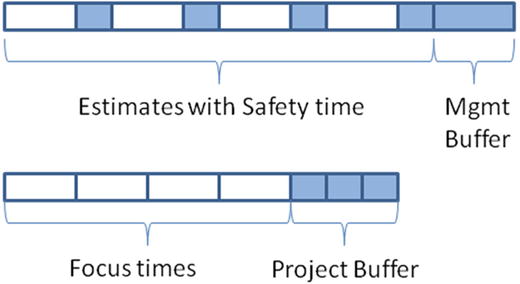

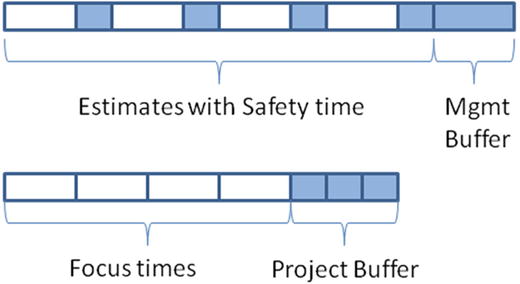

“So Tim, is this similar to using aggressive task estimates

and then putting a management buffer at the end of the project since you figure they will run late?”

Tim then draws the following diagram.

“Close, but there are some fundamental differences. A management buffer is simply adding more time to a schedule that includes safety time in it. So you are adding a management buffer to an engineering task buffered schedule. This stretches out the schedule even more. Critical Chain uses aggressive focused times and the project buffer at the end of the project is more strategic and effective. In addition, you define strategies to manage this buffer and trigger actions if the buffer is being consumed too quickly too soon, so there is more to it than a management buffer at the end of a schedule. Since the project buffer is more strategic than buffering each task, we find that we can often use less time and still get good protection against delays. To help effectively manage the project time, we also focus on behaviors to reduce bad multi-tasking and look at ways to more rigorously build the schedule, which leads us to our next two items.”

“Okay, Tim that sounds a bit more developed than what we are currently using.” I will have to bring in Gary and see what he thinks.”

Reducing Bad Multi-Tasking to Find Hidden and Misused Resource Capacity

“So Randal, have you ever driven on Highway 101 during lunch time?”

“Sure, it’s a breeze; I can often finish my work commute in 20 minutes or so.”

“And Randal, during the 5:00 rush hour, how long is your commute?”

“Horrendous. It can take up to an hour; worse if there is an accident.”

“So your commute time can actually triple, but the distance from work to your house never changed.”

“Correct.”

“So that is what we look for with

bad multi-tasking

. A highway has a certain capacity of cars it can handle. When there are not a lot of cars, traffic can flow rather quickly and just adding more cars has minimal effect. But once you start to swamp the road’s capacity, all the cars slow down more and more. The distance people have to drive has not changed, just the rate at which they can travel. The same is true with assigning projects to resources and to organizations. At a minimal point, we can just assign a handful of projects and they get done quickly—this is a reasonable amount of multi-tasking. But when we assign too many projects and all of them need to get done, the work starts to slow down more and more. This is a big sign of bad multi-tasking, where work and the time to finish our projects is getting more and more stretched out.”

“Interesting, Tim. Our engineers are getting busier and busier. And it certainly seems like they are getting overworked and are slowing down; in fact the more work we add, the more it just piles up and we have to just sit and wait for them to even get to it.”

“This is exactly what we look for in trying to address this area. Give resources clear priorities; focusing resources on key projects versus spreading them out on multiple projects; drive the resources on focused time so they focus on the key task; minimize set up and set down time; encourage quick hand-offs when tasks are completed; and don’t punish resources for finishing early or for when their tasks take longer than the focused time and consume some of the project buffer.”

“This is an interesting observation, Tim. We’ll have to go into this one a bit more when Gary is here.”

“Fair enough.”

“So Tim, project buffers and reducing bad multi-tasking are the key differences that Critical Chain has?”

“Two main differences, but let me share the last two major differences as well.”

Setting Goals and Building Schedules (Back to Front)

“So Randal, there are a variety of approaches to building a project schedule. The one key thing I have seen is that true dependencies are not always called out.”

“Okay…” Randal responds a bit hesitantly.

“In building the schedule, back to front, we first outline the goal of the project. From there, we work backward, in regard to what is essential to accomplish that goal. This helps us identify what is critical and confirm we have captured the true dependencies.”

“Tim, that kinda makes sense, but do you have a real example that I can better relate to?”

“Sure, let me give you my interpretation of one example I have seen. At the time, the industry average for building a semiconductor plant was 54 months. This was based on building the facility, installing the machines, and then training the employees. All of these areas must be operational before revenues from the project would be realized. It was a very involved and linear process. Using Critical Chain, Harris Semiconductor identified and challenged these assumptions. That, in turn, allowed them to significantly compress their entire schedule. They completed an industry average task of 54 months in 13 months. Think three and half years of additional revenue!”

“This example seems to be too good to be true, Tim. From what little I understand, semiconductor plants are extremely complex and involve very technical and experienced people to build them. And people have been building them for years. What could the whole industry miss that Harris didn’t

?”

“Using Critical Chain, Harris was able to challenge the conventional wisdom. The convention was to break the overall project into distinct and manageable sub-projects. You have one project and team build the building and once it was done then you had another project and team install the machines and only then you hired and staffed the building. One key step of Critical Chain and setting the goal of the project is to drive the project all the way to throughput, or more specifically when the plant would generate revenue.”

“You are losing me here, Tim. Why was one large project going to revenue be any better than the multiple sub-projects?”

“It changed the mindset. Instead of just focusing on the sub-project goal of finishing the building, the team was able to focus on how to get the plant operational and generating income. It drove them to think about several key and previously assumed questions. Did you really have to finish the entire building or just key parts before installing the machines? Did you really have to install all the machines before you could start hiring and training? Why could you not train people as each machine was installed and parts of the building were being finished? In this way, they were able to find ways to run large parts of these previously assumed sequential tasks in parallel.”

“Okay, I think I get you Tim. With the teams looking at revenues (throughput of the organization as you would say) as opposed to just the sub-project goals, they focused on the real value of the project. By building the schedule backward from this goal, they could really look at what items were the most important.”

“Exactly.”

“Hmm, I get the ‘set the right goal/throughput’ part. We talked about goal setting in my MBA classes. The ‘building schedules back to front’ part is more of a Gary thing. Perhaps you could walk through an example of this with him.”

“Sure.”

“Tim, goal setting and building schedules back to front does not sound like something exclusive to Critical Chain.”

“Sort of. It is an important piece of building a Critical Chain schedule. And Critical Chain looks at pulling several project management best practices together and having them reinforce each other so it creates a complete solution. You can use some pieces individually and use them with other methodologies, but you would then miss out on the full and combined benefit when you use all of the techniques together.”

“Sure Tim, synergy. The value of the parts working together is greater than the sum of their individual pieces.”

Organizational Analysis to Better Understand the Environment (Creating the CRT and FRT)

“So Randal, this is the last major piece.”

“Sounds good Tim! My head is spinning and I’m almost out of coffee.”

“So Randal, when you implement any process, its success and value heavily depend on the environment you are implementing the solution into. If the culture does not support the solution, it will not work. If the process only addresses part of the organization’s problems, then the new process may fail to work. This is true for Critical Chain, Agile, Scrum, and so on.”

“Makes sense, Tim. It also explains why some organizations have great success with a proven solution, and others fail miserably with the exact same process. The organization’s willingness to adopt the solution as well as its culture, and the nature of the organization all heavily influence the level of success. I’ve seen case studies highlighting this point time and time again.”

“So the Theory of Constraints Thinking Process (TOC TP)

provides a way to do a root cause analysis of your organizations issues. From there, you can not only see which issues the Critical Chain general solution can help you address, but, as important, you can also see what other areas you will need to work on that need to be addressed outside of the Critical Chain solution. This enables you to develop a complete and overall solution that will significantly improve your organization.”

“Makes sense. Can you possibly show me an example another time?”

“Sure.”

Mixing Multiple Project Management Methodologies

“So Randal, all of these areas come to come together to make a more rigorous project management system. We can use the organizational analysis to look at the company’s environment and use Critical Chain to ensure the projects are planned and executed based on bottom line impact and effectively manage project variability.”

“Hey Tim, what about other solutions such as extreme programming, Lean, and Agile? Are all of these mutually exclusive?”

“You can certainly mix project management methodologies, but you really need to have a solid grounding in each of the methodologies you are trying to mix. For example, I have seen people use Critical Chain for the high-level strategic schedule and use Scrum to drive the tactical deliverables into the high-level schedule. In some cases it works really well. In some cases it is put together incompletely and gets poor results. If you really want to learn more about combining methodologies like Lean, Six Sigma, and TOC, take a look at the book

Velocity

.”

Wrapping Up

“So Randal, we covered several items

:

- Common Issues that Critical Chain can help you address

- Common benefits of Critical Chain

- Some sample results

- Key components that enable Critical Chain to achieve its results and benefits”

“It’s quite a list Tim, and much more complete and thought-out than what I heard our engineering team did. Would you be able to spend some time and meet with Gary and walk through the details a bit more? He lives this project management stuff more than I do and it could end up really helping us.”

Tim paused a bit, thinking about all of the work he was getting himself into. It takes a lot of effort and commitment to put a new process, any process, into place. “Hmm, are you sure Randal?”

“Definitely,” Randal says, looking a bit excited, “I have talked to Gary several times during my internship. He really needs help and is a bit shy to ask for it. You have a really good handle on this solution and I think he would find it interesting. If we can get results even half as good as the examples you explained, it would really help us out. I’ll set up a meeting for us.”

“Sounds good, Randal. My schedule is pretty open.”

“Perfect! I’ll work with Gary to set up a meeting. I will also see if we can set you up with a brief consulting contract. I figured while you are helping us out, it couldn’t hurt to pay you a bit for your time and effort,” Randal says with a smile. “I’ll e-mail you specifics shortly.”

Current Reality Tree (CRT)

As their meeting wraps up, Randal heads out and Tim takes out a piece of paper and starts to jot down some of the issues he and Randal had discussed (items denoted as [crt #] above). Then Tim started drawing arrows on how they are loosely connected. After sketching it out, he started to review it. Then Tim hears…

“What is that?”

Looking up, Tim is a little surprised to see Randal. “I thought you left.”

“I forgot my keys,” Randal states as he waves them in front of Tim.

“I see.”

“So is your diagram related to our company?”

“Actually, it is. I had mentioned that the TOC Thinking Process organizational analysis is helpful in understanding the company’s environment. It takes a while to build and gather up all of the data to make it. Based on our conversation I wanted to sketch out a few of the items we discussed. I figured I could possibly show you the organizational analysis once it was done.” Thinking for a moment, he continues, “Then again, if you want to see what I have so far, I’m fine with sharing it with you.”

“Sure Tim. A picture is worth a thousand words. So what do you call this diagram?”

“The first page is the Current Reality Tree or CRT for short.”

Curiously, Randal inquires, “And what is the CRT diagram used for?”

“It captures the current issues an organization is facing, how they inter-relate, and what the core drivers of those issues are. This allows me to have a quick summary of your organization, see what the key issues are, and where to focus our efforts. They can get pretty complex. This one is just a summary.”

Randal

pulls up a chair, “Can you walk me through it?”

“Um, sure,” Tim says, feeling a bit odd. Usually he waits until someone has gotten more familiar with Critical Chain or TOC before sharing an analysis.

Randal stares at it briefly, trying to figure it out and then asks, “So is there a special way you are suppose to read it?”

“Sure,” says Tim and he proceeds to review the CRT with Randal.

“So Randal, the CRT is like a logical proof based on

if-then logic and dependencies. For now, I am just sketching out some of the issues and connecting them with rough logic and long arrows. From example, starting at the bottom of the chart if 14) too many resources leave the company, then one consequence is that 13) departments get stretched out.”

“Makes sense, I guess. As we unfortunately lose people, it will add pressure to the department that lost that person. What about the other arrows?”

Tim continues, “The stretched out departments lead to 15) schedules slipping.”

“Kinda of a jump there, Tim. If resources leave, well, sure it puts pressure on the schedules, but there are other reasons why our schedules slip.”

“True. Like I said it is with long arrows, but as you noted it is insufficient by itself. There are other issues that impact schedules that we’ll need to capture.”

“Fair enough.”

“So continuing, 13) departments being stretched and 15) the slipping schedules lead to 18) resources for future projects are being delayed.”

“Makes sense. We are trying to get the current projects out so the future projects suffer.”

“Yes. 15) We slip schedule then 19) and 20) cutting corners will keep us on schedule that leads us to 23) we’ve cut too much and we’re not competitive.”

“Yuck, I see that on both sides. Engineering is under pressure to make deadlines and marketing is complaining that our products are not competitive enough.”

“Then 23) being not competitive leads to 26) we miss our expected revenues. And in addition to that, 15) we slip schedules leads to 25) we miss market windows and lose contracts, which also leads to 26) we miss revenues and finally that leads to 28) the company goes bankrupt.”

“Not very pretty, Tim. But yes in a rough way you seem to have captured our concerns. Is there a bright side to this analysis?”

Future Reality Tree (FRT)

“Sure Randal. The Future Reality Tree is the vision of where we want to move. It includes key items we need to put into place and the benefits we want to obtain.” Tim then takes out a second sheet of paper and jots down some of the desired benefits he and Randal discussed before (items denoted as [frt #] above).

“Starting at the bottom of the chart, if we 1) set up project buffers, reduce bad-multi-tasking, set clear goals, define the project in terms of throughput, and build schedules back to front, we then will 6) successfully implement Critical Chain.”

“I am guessing, Tim, that is not the only step we need to implement Critical Chain?”

“No, it is a key one though. As we go through the implementation, I will need to add others. Continuing, once 6) Critical Chain is implemented then 7) our schedules can better handle delays, which leads us to 8) we can better meet or beat deadlines.”

“I like the sound of meeting or beating our schedules. But we have a lot of challenges and we have tried several things to improve our schedule performance. This looks a bit light.”

“True Randal; it is just a start. We will need to add several more items to strengthen our ability to meet or beat our schedules.”

“I also added if we have 7) better schedules then 12) department resources are better balanced. If we have 8) better delivery dates then 15) future resources should be more available.”

“Okay.”

“Building off 8) have better schedules then 14) our products can be more competitive and then 20) we can have better revenues. In addition, 8) better schedules leads us to 17) meeting key customer deadlines, 18) increased sales, 20) meeting revenues, and 21) the company being more profitable.”

”It sounds like it is in the right direction, Tim. A bit thin, but promising. I am curious to see how your diagrams build out. For now, I’ll set up that meeting with Gary and we can see where things go from there.”

“Sure, Randal.”