CHAPTER 5

Market Cycle Risk

________________

In an ideal world, investors and policymakers would have perfect foresight, enabling them to accurately predict future events. Central bankers would predict the actions of consumers and businesses and proactively implement fiscal and monetary policy that generated a steady level of economic growth while keeping inflation contained. Business leaders would anticipate changes in demand for their products and services and adjust output accordingly to grow their earnings at the highest possible rate. Investors would precisely forecast future corporate earnings and thereby accurately determine the fair value of each company.

Unfortunately, reality is nothing like this. No one can predict the future with any certainty. At best, we can make educated guesses of what may come, where the probability of being correct is hopefully greater than 50%. Even the most rational decision-maker is subject to the whims of the infinitely complex world we live in. In the words of Howard Marks, “[t]he reason for this—as I've harped on repeatedly—is the involvement of people. People's decisions have great influence on economic, business and market cycles. In fact, economies, business and markets consist of nothing but transactions between people. And people don't make their decisions scientifically.”1 Does not being able to foresee all possible events or know the probability of events occurring or the eventual impact they will have on our investment portfolio mean that trying to manage risk is hopeless? Not at all. What it does mean is that as investors, we need to accept that there is a high degree of uncertainty when investing and, to the best of our ability, strengthen our understanding of the risks we face and plan for potentially negative outcomes. It is at the extremes, when discipline matters most, that our instinct to panic kicks in and leads us astray. Having a game plan in advance of these moments is a critical ingredient of investment success.

The market cycle is characterized by periods of expansion and contraction in company valuations, driven by rising and falling profitability coinciding with peaks and troughs in investor sentiment. By definition, investor sentiment reaches an extreme high at the peak of stock market valuations and an extreme low at the trough of stock market valuations. Failing to understand how market cycles work and how we should respond as investors is perhaps the most common cause of investment losses.

Economic Cycles

Economies are comprised of people, making them subject to the same behavioral biases discussed earlier, resulting in bouts of extreme optimism and pessimism. Taken as a whole, this causes countries to experience recurring periods of expansion and contraction in economic output, a phenomenon referred to as the economic, or business, cycle.

Economic cycles are self-perpetuating, meaning that the conditions that create an economic boom inevitably cause an economic bust that in turn leads to another boom. As the cycle repeats itself, each iteration takes on distinctive characteristics, which ensures that the exact duration and extent of every cycle remains unpredictable. The cycle occurs in part because of our inability to predict the future. When the economy is growing, jobs are plentiful and home prices tend to rise, creating wealth for consumers, and leading them to become increasingly optimistic. During these times, consumers begin to spend more on goods and services and businesses respond by increasing supply to meet this heightened demand. This leads to more jobs and accelerates wealth creation even further. At some point in time, however, there are not enough people in the workforce to fill all job vacancies and businesses must increase wages to attract the employees they require. In addition, demand for raw materials needed in the production of goods increases, eventually causing prices of those inputs to rise. The combination of these factors causes the cost of goods produced to rise, forcing businesses to raise the prices they charge consumers and thereby causing inflation.

As inflationary pressures build and threaten the economy, central banks intervene to slow economic growth by raising interest rates. As noted earlier, higher interest rates lead businesses to cut back on production, thereby reducing employment. This causes the overall level of demand to fall as consumers become less optimistic. As the demand for goods falls, prices begin to decrease, causing businesses to slow production and reduce employment. As unemployment levels trend higher, house prices begin to decrease, causing consumers to become increasingly pessimistic and save rather than spend their money. This reduction in demand causes businesses to cut back even further on production and to for go or delay projects that would otherwise have aided economic growth. If the central bank is successful in creating a soft landing, the rate of economic growth will slow down but remain positive while inflationary pressures decrease.

When it is clear that economic growth is likely to weaken below an acceptable level, central banks try to stimulate the economy by lowering interest rates. This increases the amount of money in the financial system, enticing businesses to invest and consumers to spend. These lower interest rates will again cause businesses to anticipate stronger future demand and resume hiring, thereby leading to an improvement in consumer sentiment and spending. Almost without fail, the corporate sector overinvests and adds too much capacity when times are good and reduces capacity too much when times are bad. This process exacerbates the swings in overall levels of supply and demand across the economy and forms a cycle as the process repeats itself.

Central bank intervention combined with longer-term population and economic growth mean that economic expansions tend to last longer than contractions. According to the National Bureau of Economic Research, the average economic expansion in the United States has had a duration of approximately 64 months while the average economic contraction has averaged approximately 10 months.2 As previously mentioned, two or more consecutive quarters (six months) of negative growth is considered to be a recession, while prolonged periods of extreme economic weakness are referred to as depressions. In modern times, a depression has only occurred once, beginning in most countries in 1929 and lasting well into the 1930s. By the time the economy in the United States bottomed in 1933, the Great Depression caused real GDP in the United States to fall by 30%, and the wholesale price index to fall by 33%.3 It was so devastating to the world economy that the effects of the Great Depression were felt as late as the end of World War II in some countries. The global financial crisis of 2007–2009 was milder by comparison, with US GDP falling by only 4.3%, but the world economy still lost millions of jobs, with unemployment almost doubling to 9.5%.4 In both cases, the economic weakness that followed led to a period of austerity, where both businesses and individuals were able to strengthen their finances and reduce their debt levels. As well, the market selloffs that resulted from these periods of financial turmoil brought stock valuations once again to attractive levels and created the conditions for a new bull market to emerge.

Market Cycles

The term “market cycle” refers to a recurring pattern in the general level of stock prices that are the direct result of the economic cycle and therefore display a similar sequence. The reason is that the same forces driving the economic cycle impact corporate profitability. As the economy improves, corporate earnings increase, and share prices appreciate. As the economic outlook deteriorates, share prices fall in anticipation of weaker corporate earnings in the future. Since the financial markets are always forward-looking, share prices and actual earnings do not peak and trough at the same time. Instead, share prices usually peak before earnings start to fall and rise before earnings begin to recover. In fact, stock markets usually peak and trough six to nine months before the economy. Figure 5.1 provides a simplified representation of the full stock market cycle.

As with economic cycles, market cycles can be broken down into distinct periods, each with unique characteristics. The most basic distinction to be made is between a bull and a bear market. A bull market refers to a period when share prices in general are rising, whereas a bear market exists when share prices in general are falling. More specifically, a bear market is typically considered to be a period in which share prices fall by at least 20%. A drop in share prices of less than 20% is referred to as a bull market correction. For the purposes of this book, I have classified severe bull market corrections as bear markets, even though they are not generally regarded as such. Examples of severe bull market corrections include the market selloffs that occurred in 2011 and 2018, during which stock prices fell by more than 20%, but which did not coincide with an economic recession.

FIGURE 5.1 The Stock Market Cycle

Since bull markets are associated with strong or improving economic environments and bear markets coincide with weakening economic environments, bear markets tend to be shorter in duration than bull markets, each averaging 370 and 1,446 calendar days, respectively. Bear markets are often followed by a repair phase, in which the market rallies but then retests the earlier lows before entering a new bull market. However, there have been cases where the market formed a V-shaped bottom, rising quickly off the low, essentially skipping the repair phase of the cycle. One example of a V bottom is the 2020 bear market, when markets rallied strongly and did not retest the previous lows. On average, it has taken the stock market 717 calendar days to fully recover to its previous high following a bear market.

Bull markets can be broken down further into an early, mid-, and late cycle. The beginning part of a bull market cycle is known as the early cycle and it refers to the period when share prices have reached a bottom and are beginning to recover. The late cycle refers to the later stages of a bull market when share prices are reaching a peak. The mid-cycle is the period between the early and late stages of the market cycle. While the middle stage of the market cycle tends to be characterized by steady economic and earnings growth, there are usually one or more pauses that are referred to as mid-cycle slowdowns. These pauses may manifest themselves as a temporary slowdown in the rate of earnings growth and a mild drop in share prices (typically between 5 and 10%). Long-running bull markets may have more than one mid-cycle slowdown. The table in Figure 5.2 provides a summary of bear markets experienced by the S&P 500 Index since 1927, including how long they lasted and how much share prices fell in each instance. Again, this list includes all market corrections in which share prices fell by 20% or more.

While the average bear market caused stocks to drop approximately 36% and last 370 days, some were much shorter in duration. Market analysts typically focus on the size and duration of the drop in share prices; however, what is really important is the impact a bear market has on investor psychology. There are several market selloffs that are not listed in Figure 5.2 because they do not quite meet the somewhat arbitrary 20% minimum threshold for a bear market. And yet because of the time frame in which they occurred, these selloffs had the effect of wiping the slate clean and removing enough excessive optimism to allow the market to continue higher, thus prolonging the official bull market. The bear markets with the most profound effect on investor psychology, and that therefore take longer for investors to recover from, are those that are both deep and long lasting, such as the bear markets of 1929 to 1932 and 2007 to 2009.

FIGURE 5.2 A History of Bear Markets and Severe Bull Market Corrections

Data source: Standard & Poor's Financial Services LLC, sourced via Bloomberg, as of January 15, 2022.

Investors should also note that bear markets often contain strong temporary rebounds in share prices that are referred to as bear market rallies. Similar to bull market corrections, these are temporary but sometimes violent reversals in the underlying trend that have the potential to entice investors into buying stocks even though the bear market has further to run.

Market corrections and bear markets present opportunities. They are a necessary part of the market cycle that provide the foundation for continued growth, and they provide investors with the opportunity to buy great businesses at discounted prices. These moments are when it is most important to remain objective, and the best way to do that is to have a plan laid out before they occur. In this manner you can invest your money in a way that protects your portfolio from the negative impacts of market selloffs, while still allowing you to take advantage of the opportunities that are created by them.

Knowing approximately where we are in the market cycle can provide you with a tremendous advantage as an investor. Different asset classes and businesses perform well or poorly, depending on where we are in the market cycle. This knowledge can be a powerful tool when it comes to managing risk in your portfolio and seizing opportunities when they arise. To be clear, market timing is not the goal. As we noted earlier, it is impossible to know exactly when the market will turn from a bull to a bear market and vice versa. Regardless, if you are aware they exist and are looking for them, there are signs that should help you determine what part of the market cycle we are currently in with a reasonable degree of accuracy. To do this, though, we need a better understanding of the various stages of the market cycle and what underlying forces are at work in each stage.

Early Cycle

The early stage of the market cycle refers to the period instantly following a bottom in share prices for the broader stock market. It is important to look at the broad stock market because not all company share prices will reach a low at the same time. Certain businesses will have already started to improve by the time the stock market bottoms, while still others will see their earnings (and share prices) continue to fall.

Consider the early stage of an economic expansion. The economy has just gone through a period of weakness. Unemployment levels have increased, and interest rates have most likely been reduced by the central bank to encourage spending and spur economic growth. Businesses begin to expect a recovery in demand and start to hire back employees they previously laid off. If business leaders are less certain of the sustainability of the economic recovery, they may choose to hire temporary workers initially, with plans to hire permanent workers once they have greater confidence in the economic recovery. Under these circumstances, certain types of businesses will perform better than others. Also, investors will begin to invest in cyclical businesses as a new bull market emerges, since these businesses are more levered to economic growth, and they benefit the most when economic growth improves. Depending on what caused the preceding bear market, the early stages of a new bull market may be dominated by a strong rebound in the share prices of companies that suffered the greatest losses in the downturn. A notable example is found in the immediate aftermath of the 2020 pandemic-driven bear market, when the share prices of energy companies, one of the worst-performing sectors during the crisis, were among the strongest short-term performers once the market correction ended.

Mid-Cycle

As the economic recovery takes hold and it becomes clear that economic growth will be sustained, the bull market enters the middle part of its cycle. This mid-cycle stage can be long in duration and is characterized by broad-based strength in stocks. Mid-cycles typically experience one or more temporary slowdowns or pauses in economic growth, at which time stock prices either fall modestly (5–10%) or go sideways for a time. At these junctures, the market often experiences some degree of rotation out of stocks that have performed well into stocks that had been lagging. This process improves the state of equilibrium within the market and helps to create the conditions necessary for the market to advance once again. As the economic expansion progresses, however, prices start to rise as wages and other input costs go up, raising the specter of inflation. The prospect of higher inflation causes market participants to begin to predict higher interest rates, at which point the stock market enters the late stage of the cycle.

Late Cycle

The late-cycle stage of a bull market is characterized by a peak in corporate earnings and profitability. At this point in time the underlying economy has grown considerably, and businesses have generated significant profits and invested heavily in their operations to add to their productive capacity. Jobs are plentiful and companies must increase wages in order to hire and retain employees. Commodity prices have increased due to stronger demand from businesses and consumers. Stronger demand drives oil and gas prices higher and helps the shares of energy companies, causing them to outperform in the late stage of the market cycle. As the general level of prices begins to rise, however, central banks begin to increase interest rates to contain inflation. In turn, higher interest rates affect businesses differently. Banks, for example, typically benefit from modest increases in interest rates because their net interest margin (NIM) expands. NIM is the difference between the interest banks must pay on savings accounts and the interest they receive from lending money. NIM expansion makes banks more profitable and so they tend to perform well during the initial stages of an interest rate–tightening cycle. Shares of high-growth, high-valuation companies that generate little or no earnings, on the other hand, tend to perform poorly as interest rates move higher. The reason for this is simple: rising interest rates reduce the value of earnings and cash flows by a greater amount the further out into the future they are expected to occur. The process of adjusting future cash flows in this manner is referred to as “discounting,” which we discuss in greater detail in Chapter 8.

Gradually, as economic growth begins to slow, investors are inclined to shift assets away from cyclical businesses to those that are more defensive, such as those within the utility and healthcare sectors. The term “defensive” refers to companies that have consistent earnings, regardless of whether the economic environment is weak or strong. This stable earnings profile provides downside protection, causing the share prices of defensive companies to fall less in bear markets. Toward the very end of the market cycle, credit spreads typically start to trend higher and may even increase rapidly, although they do not “blow out” except in the event of a credit crisis. Rising credit spreads serve as a sign of heightened risk in the stock market.

Sector Rotation

As noted earlier, the market cycle is marked by what is commonly referred to as sector rotation. Sector rotation is created when investors collectively shift their funds from one market sector to another in response to expected changes in economic conditions. As the economic cycle evolves, various sectors and industries will perform better than others. This creates smaller industry- or sector-level cycles within the broader market cycle. One method for identifying sector rotation is to monitor business news flow. While the normal condition is for companies to respond favorably to good news, as good news is absorbed by market participants and businesses become more expensive versus the broader market, share prices stop responding favorably to good news. This can be an early sign that all good news has been factored into current share prices and that businesses in the sector have become fully valued (or overvalued) and are likely to underperform in the near term. At this point it may be best for the investor to reassess those holdings in light of the current stage of the market cycle and consider whether it is prudent to take profits in those businesses and reallocate the capital to better opportunities. The same is true when the share prices of businesses in a sector stop reacting poorly to unwelcome news. It is at this point that all unwelcome news could be priced into those shares, and they may be due for a recovery.

Market Contagions

Weakness in one segment of the global financial markets has the potential to infect other areas of the market that are otherwise performing well. This phenomenon is known as a market contagion. It is difficult to predict whether a particular area of weakness may affect other segments of the global equity market. What might seem to be a significant event could turn out to be contained at the regional or country level, while something seemingly inconsequential could grow into a serious problem.

A number of the bear markets listed earlier in Figure 5.2 were the direct result of market contagions. While it started off as a regional crisis, the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis is a notable example. Currency devaluations in South Asia caused regional stock markets to fall, but eventually fear spread to other parts of the world, impacting the United States in October 1997 and causing the S&P 500 Index to fall 13% from its peak. This is shown in Figure 5.3, where the crisis in Asia took several weeks to affect European and North American equity markets.

Once it was clear that the situation in Asia had stabilized, equity markets around the world began to recover at approximately the same time. Unlike the Asian Financial Crisis, the global financial crisis, which began in the United States in October 2007, very quickly reverberated throughout financial markets, causing most of the world's equity markets to enter a bear market at the same time. Other examples of market contagions include the 2012 European debt crisis, and the Long-Term Capital Management crisis of 1998.

FIGURE 5.3 Market Impact from Asian Financial Crisis

Data source: Standard & Poor's Financial Services LLC, sourced via Bloomberg, as of January 30, 2022.

Bear Market Warning Signs

Any number of factors can cause an equity bull market to end, highlighting the importance of monitoring signs that may provide an early warning of market turmoil. Being aware of the potential for a banking crisis is paramount, in which inflated housing prices can play a significant role. Economic professors Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff explain that “[f]or banking crises, real housing prices are nearly at the top of the list of reliable indicators, surpassing the current account balance and real stock prices by producing fewer false alarms.”5 An extended period of housing price increases has been behind many banking crises in the past, especially when they have resulted from easy lending standards and artificially depressed mortgage rates.

In fact, changes in the general level of asset prices may hold clues as to when the next financial meltdown will occur and how severe it will be. Extended periods of share price appreciation combined with historically high valuations, abnormally low credit spreads, and easy lending conditions, along with widespread apathy to potential risks and a general feeling that the good times will just keep going, are all warning signs that the stock market is vulnerable to a correction. The longer these conditions last and the more extreme they become, the deeper and more prolonged the market selloff is likely to be.

Another important statistic to monitor is the amount of margin debt in the financial system. Margin debt is the amount of money investors have borrowed to buy stocks. Margin debt helps support the stock market as investors continue to borrow and buy shares, but it is detrimental for the market when investors must sell those shares to repay the loans. Most margin debt exists in brokerage accounts and bank loans, and these monies must be repaid regardless of how well the equity markets perform. If stock prices were to fall beyond a certain point, margin debt may be “called” by the lender, forcing investors who borrowed the funds to sell stocks at the lower prices to repay their loans. This is known in the investment industry as a margin call, and enough of them occurring at the same time can increase selling pressure and cause share prices to fall even further. High rates of growth in margin debt are a sign of excessive investor optimism and should be a warning sign for you as an investor. Figure 5.4 shows the year-over-year change in margin debt in the United States.

Periods of large increases in margin debt preceded every major bear market since 1998. Although this data is not available in all countries, the prominence of the US equity market allows us to use this data to gauge the overall amount of leverage in the global financial system.

As noted in Chapter 4, the bond market can also hold clues to the future of equity markets, with credit spreads being a crucial factor. Rising credit spreads can point to growing aversion to risk and a tougher lending environment and are a potential red flag for equity markets. Without a large corresponding increase in credit spreads, market selloffs will most likely be short-term corrections rather than the start of a bear market. In a study completed in 2018, Morgan Stanley Research noted that “credit in general tends to be the first to ‘crack,’ providing a bearish market signal 3–12 months in advance, with government bond yields, on average, peaking about three months before [the MSCI] ACWI [Index] and S&P 500 [Index] do.”6

FIGURE 5.4 Year-over-Year Change in US Margin Debt

Source: The Financial Industry Regulatory Authority Inc. (FINRA), https://www.finra.org/investors/learn-to-invest/advanced-investing/margin-statistics, accessed January 16, 2022.

In addition, changes in the level of interest rates play a key role in the future earnings power of companies. Rising interest rates may place equity markets at risk, depending on their level and the rate of increase. From exceptionally low levels and when economic growth is strong, moderate interest rate increases are often viewed as being positive for equity markets. The reason is that it shows that central banks believe that economic growth will continue at a healthy pace, and that inflation will remain contained. If interest rates rise quickly on the other hand, it could be a sign that inflationary pressures are mounting and that the central bank will have to raise rates to slow economic growth, thus dampening corporate profits. Monetary tightening by central banks is another sign that a bull market is in the late stages of an expansion.

Last, the relative performance of industry sectors can provide clues as to where we are in the market cycle. As the cycle nears an end, defensive businesses start to outperform the broader stock market. Then, as the market reaches a bottom or trough, cyclical businesses such as technology, financials, discretionary, industrials, and materials start to outperform.7 In a related fashion, value stocks typically start to perform better than growth stocks, and safe-haven currencies like the US dollar, Swiss franc, and Japanese yen begin to outperform emerging market currencies at stock market peaks. In addition, Japanese and European equities usually begin to outperform US and emerging market equities at market peaks.8

Taken together, rapid interest rate hikes by central banks, widening credit spreads, improving performance of defensive company shares versus cyclical company shares, value indices outperforming growth indices, a recent period of excessive growth in margin debt, in combination with inflated stock and housing prices, should set off alarm bells for investors. Keep in mind, though, that no two market cycles will be identical. In fact, the exact same point of progression will differ in meaningful ways between two distinct market cycles. Simply put, the warning signs just listed may not all be present at the start of a bear market. However, an abundance of these red flags should allow you to mentally brace yourself for a market correction or bear market by figuratively “putting on your crash helmet.” Let us assume for a moment that the previously mentioned warning signs are present, and you believe that a bear market is imminent. What should you do? The answer lies in the past—what you have done leading up to this point. The type of businesses you have invested in and the way you construct your portfolio are the best way to protect yourself from a bear market. If you have prepared yourself and your portfolio for these moments, as we outline throughout this book, you will see bear markets as opportunities and look forward to them rather than fear them. Don't fear the bear, stay calm and outsmart it.

Bear Market Bottoms

Bear market bottoms are often marked by a rapid reduction in interest rates by central banks, falling credit spreads, low equity valuations, and waning relative outperformance of defensive sectors in the market. Investors should monitor central bank statements closely to gauge potential inflection points. Signs that a bear market has ended include the outperformance of small-cap versus large-cap stocks, as well as high-beta versus low-beta stocks. Although the definition of small and large cap varies by country, in the United States small-cap stocks are generally regarded as companies with a total market capitalization (value) of less than US$2 billion, while large-cap stocks are those with market capitalizations greater than US$10 billion. The term “beta” is discussed in more detail in Chapter 8, but it essentially refers to how much a company's share price moves in relation to the overall stock market, with high-beta stocks being more leveraged than low-beta stocks to price changes in the stock market.

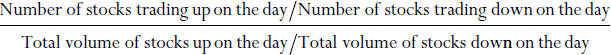

Trading volume and market breadth also play a key role in identifying market bottoms. One useful measure is the Arms Index, which investors also refer to as the TRIN. The market's TRIN is measured as the ratio of advancing to declining stocks, divided by the ratio of advancing to declining volume, and can be calculated as follows:

A TRIN reading above 1 is usually associated with a decline in the stock market, driven by a proportionally high level of selling volume. Conversely, a TRIN reading below 1 is associated with a rising stock market since there is a proportionally greater volume going into advancing stocks. A high TRIN reading (above 2) followed by a low TRIN reading (0.50 or less) may indicate capitulation selling followed by a volume thrust and is often associated with bear market bottoms. This may be especially relevant when followed by a breadth thrust, which is another sign that a market recovery is likely to continue. There are different variations or definitions of a breadth thrust, but one useful approach is to identify when most stocks in the market are trading at new 65-day highs. This is particularly relevant when these new highs occur after market breadth collapses, signaling capitulation on the part of investors. I highly recommend following Jeff deGraaf and the team at RenMac on social media for timely insights into many of the factors used to identify bear market bottoms. Particularly when markets have already fallen significantly (20–30% or more), it is at these moments that you should begin putting more money back to work and buying shares of the companies you want to own.

Managing Cycle Risk

The biggest risk for investors stemming from market cyclicality is selling when share prices have already fallen significantly. Conversely, buying after share prices have appreciated considerably also poses risks and has the potential of reducing forward investment returns. Focusing on the future earnings power of the business and the price being paid for those earnings will alleviate both pitfalls. This discipline will keep you from selling when other investors are panicking and share prices are bottoming, and from buying when investors are exuberant and share prices are peaking. Share prices peak when the last buyer buys and bottom when the last seller sells. It is therefore the absence of buyers that causes stock markets to peak, rather than a sudden surge in selling. Similarly, it is the absence of sellers that allows stocks to finally reach a bottom.

The good news is that there are some simple steps that investors can take to manage cycle risk in their portfolio. First, own good businesses. The high-quality businesses that were described briefly in Chapter 1 can withstand economic downturns better than their weaker competitors. These companies can keep their leadership position when times get tough and can generate a more consistent level of earnings. They may also be able to take advantage of a crisis by taking market share or buying companies with good assets that are more vulnerable to economic weakness and find themselves in distress. Diversify your portfolio by industry. Remember that the share prices of companies in the same industry tend to move in tandem. Owning several companies in the same industry will therefore not protect you as much as owning businesses in a variety of industries. In addition, owning businesses whose shares are denominated in different currencies can further help reduce portfolio risk. The topic of portfolio construction is discussed in more detail in Chapter 20.

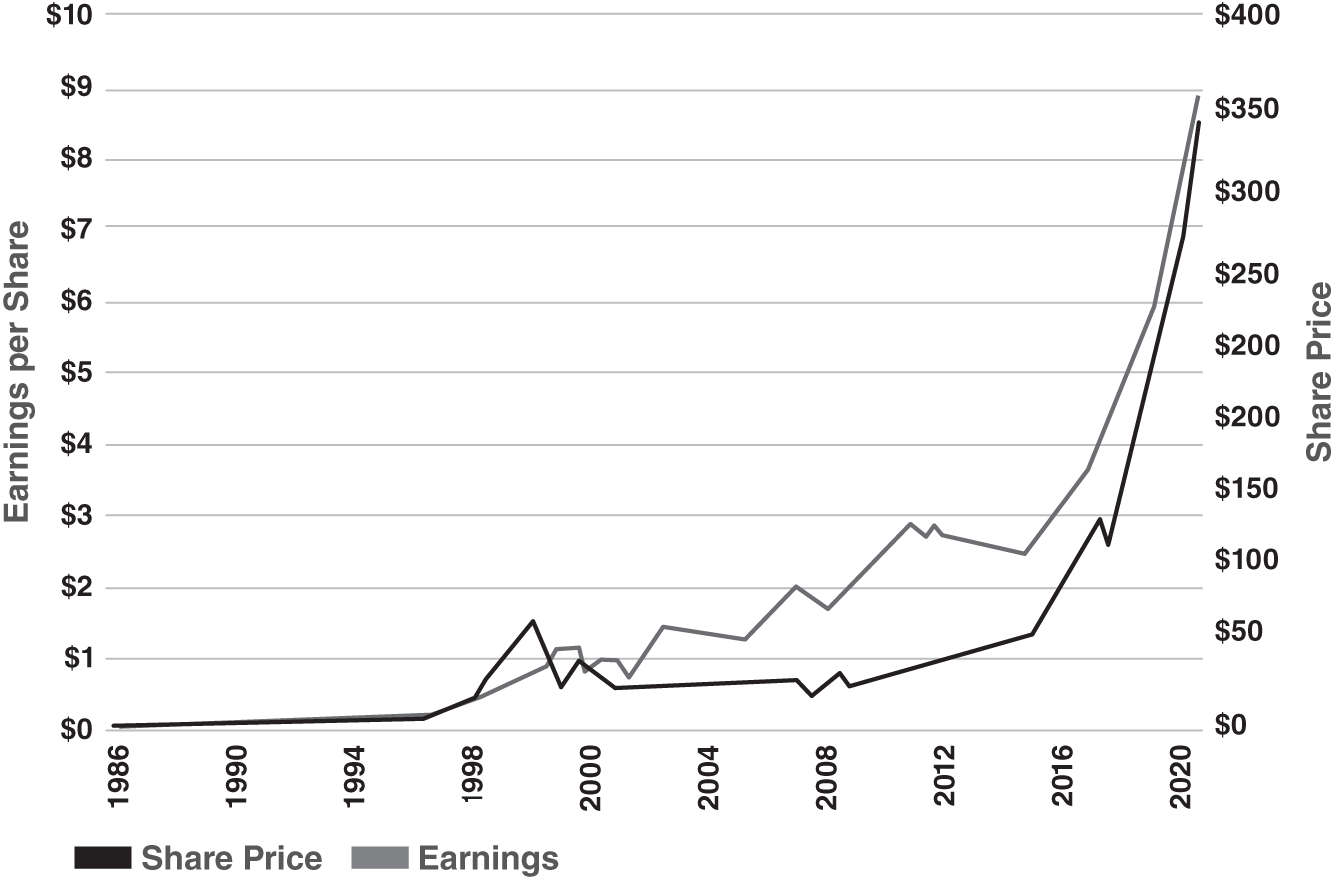

Remain focused on being an owner of a business, rather than an owner of shares. This is an important psychological factor during bear markets. In some cases, the share price of a company may drop in a market correction while its earnings remain steady. Figure 5.5 shows how the earnings for Microsoft remained fairly consistent or continued to rise despite large drops in the share price during the tech bubble of 2000–2002 and the financial crisis in 2008. By focusing on the company's earnings and its ability to withstand tough economic times, you will be better able to look past temporary share price volatility.

Investors will be well-served remembering that nothing in the investing world is definite, and that rules are made to be broken. Ted Ransby, one of my early mentors in the investment industry, described the stock market in this way: “[T]he market will bend the rules just enough to push investors past their breaking points.” Ted aptly described the capitulation stage of the market cycle, where investors cast aside fundamentals and logic and react based purely on emotion. The fact that no two cycles are identical is crucial to the perpetuation of the market cycle process. It is only when the majority of investors are fooled into thinking the current trend will not end and they finally give in to buying or selling that markets peak or trough. Remember that markets peak when the last investor buys and bottom when the last investor sells. You do not want to be either of those investors—buying at the peak or selling at the bottom.

FIGURE 5.5 Microsoft Earnings versus Share Price

Data source: Bloomberg and Yahoo Finance, as of February 6, 2022.

That leads us to the next point, which is to buy more of the great businesses you like when they become less expensive. Ownership positions are on sale at this point so why not take advantage of that? Another possibility is to consider shifting some money into businesses that you really like but that you felt were too expensive to buy previously. If you can do this effectively, you have succeeded in flipping conventional thinking on its head, and view falling share prices as an opportunity rather than a threat.

One final technique used to limit market cycle risk worth mentioning is to rebalance your portfolio on a regular basis. Rebalancing requires you to sell a portion of the stocks you own that have done especially well and use the proceeds to add to those that have lagged. Sticking with this consistently will help you reduce risk by redistributing money away from more expensive stocks to those that on average are less expensive. This approach is based on the concept of mean reversion, where valuations will tend to revert back to their long-term average. Stocks trading below their long-term average valuation will eventually rise until they reach it, while stocks trading above their long-term average valuation will eventually fall back down to it. The topic of portfolio rebalancing is discussed in more detail in Chapter 20.

This chapter provided a brief overview of why market cycles occur, what these cycles mean for you as an investor, and how you can manage the risks that arise from this cyclicality. For a more in-depth and insightful discussion on market cycles, I strongly recommend that you read Mastering the Market Cycle by Howard Marks. We now consider the risk that foreign currencies bring to global investing.

Notes

- 1. Howard Marks, Mastering the Market Cycle: Getting the Odds on Your Side (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2018), p. 289.

- 2. National Bureau of Economic Research, “US Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions,” https://www.nber.org/research/data/us-business-cycle-expansions-and-contractions, accessed January 16, 2022.

- 3. Britannica, “Great Depression,” https://www.britannica.com/event/Great-Depression, accessed January 16, 2022.

- 4. Britannica, “Great Recession.”

- 5. Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff, This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly (Princeton University Press, 2009), p. 279.

- 6. Morgan Stanley, “A Spotter's Guide to Bull Corrections and Bear Markets,” March 4, 2018.

- 7. Morgan Stanley, “A Spotter's Guide.”

- 8. Morgan Stanley, “A Spotter's Guide.”