In This Chapter

Introducing AdWords

Understanding the difference between AdWords and other forms of advertising

Getting an overview of direct marketing

Seeing AdWords through your prospects' eyes

Have you ever bought an ad in the Yellow Pages? I remember my first time — I was terrified. I didn't know what to write. I didn't know how big an ad to buy. I wasn't sure which phonebooks to advertise in. I had no idea what headings to list under. I had to pay thousands of dollars for an ad I wouldn't be able to change for the next 12 months. And I had recurring nightmares that I mistyped the phone number and some baffled florist in Poughkeepsie got thousands of calls from my customers.

Why am I telling you this? (Aside from the fact that my therapist encourages me to release negative emotions?) Because I want you to appreciate the significance of Google AdWords as a revolution in advertising.

You can set up an AdWords account in about five minutes for five dollars. Your ads can be seen by thousands of people searching specifically for what you have, and you don't pay a cent until a searcher clicks your ad to visit your Web site. You can change your ad copy any time you want. You can cancel unprofitable ads with the click of a mouse. You can run multiple ads simultaneously and figure out to the penny which ad makes you the most money.

You can even send customers to specific aisles and shelves of your store, depending on what they're searching for. And you can get smarter and smarter over time, writing better ads, showing under more appropriate headings, choosing certain geographic markets and avoiding others. When your ads do well, you can even get Google to serve them as online newspaper and magazine ads, put them next to Google Maps locations, and broadcast them to cell phones — automatically.

AdWords gives you the ability to conduct hundreds of thousands of dollars of market research for less than the cost of a one-way ticket from Chapel Hill to Madison. And in less time than it takes me to do five one-arm pushups (okay, so that's not saying much).

AdWords can help you test and improve your Web site and e-mail strategy to squeeze additional profits out of every step in your sales process. It can provide a steady stream of qualified leads for predictable costs. But AdWords can also be a huge sinkhole of cash for the advertiser who doesn't understand it. I've written this book to arm you with the mindsets, strategies, and tactics to keep you from ever becoming an AdWords victim.

The Google search engine, found at www.google.com, processes hundreds of millions of searches per day. Every one of those searches represents a human being trying to solve a problem or satisfy an itch through finding the right information on the World Wide Web. The AdWords program allows advertisers to purchase text and links on the Google results page (the page the searcher sees after entering a word or phrase and clicking the Google Search button).

You pay for the ad only when someone clicks it and visits your Web site. The amount you pay for each visitor can be as low as one penny, or as high as $80, depending on the quality of your ad, your Web site, and the competitiveness of the market defined by the word or phrase (known as a keyword, even though it may be several words long) typed by the visitor.

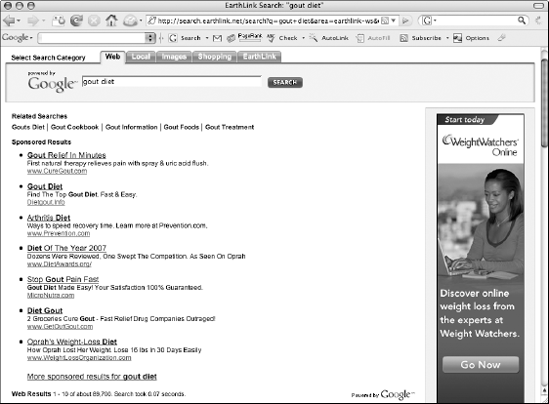

Each text ad on the results page consists of four lines and up to 130 characters (see Figure 1-1 for an example ad):

Line 1: Blue underlined hyperlinked headline of up to 25 characters

Line 2: Description line 1 of up to 35 characters

Line 4: Green display URL (URL stands for Uniform Resource Locator, the way the Internet assigns addresses to Web sites) of up to 35 characters

The fourth line, the display URL, can differ from the Web page your visitor actually lands on. I cover this in detail in Chapter 6.

You can choose to show your ads to the entire world, or limit their exposure by country, region, state, and even city. You can (for example) let them run 24/7 or turn them off nights and weekends. You also get to choose from AdWords' three tiers of exposure, described in the following sections.

When someone searches for a particular keyword, your ad displays on the Google results page if you've selected that keyword (or a close variation) as a trigger for your ad. For the ad shown in Figure 1-1, if someone enters kids asthma prevention in Google, they can view the ad somewhere on the top or right of the results page (see Figure 1-2).

Your ads can also show on Google's search partners' network. Companies such as AOL and EarthLink incorporate Google's results into their search pages, as in Figure 1-3.

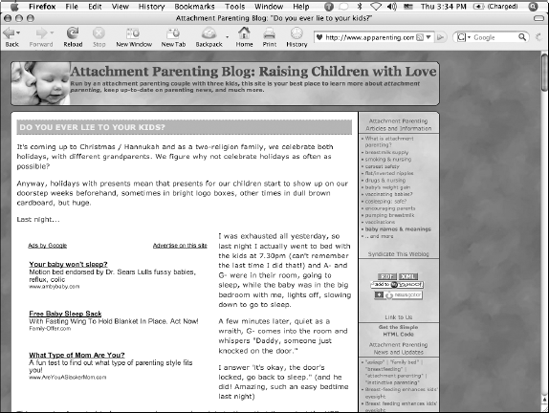

Additionally, hundreds of thousands of Web sites show AdWords ads on their pages as part of the AdSense program, which pays Web site owners to show AdWords ads on their sites. (See Figure 1-4 for an example.) Think of an online version of a newspaper or magazine, with ads next to the editorial content. The content of the page determines which ads are shown. On sites devoted to weightlifting, for example, Google shows ads for workout programs and muscle-building supplements, rather than knitting and quilting supplies. Google lets you choose whether to show your ads on this Content network, or just stick to the search networks.

Although anyone with a Web site can use the AdSense program, Google has a special relationship with some of the most popular content sites on the Web, including

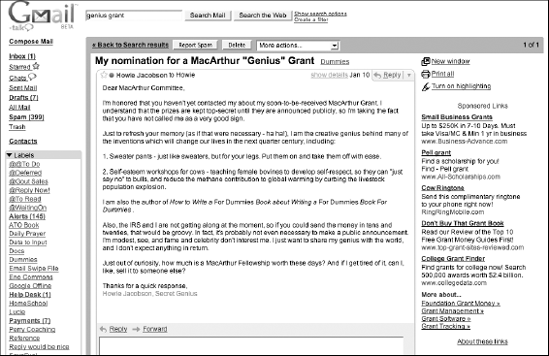

Gmail is Google's Web mail service. It displays AdWords results to the right of the e-mail you receive. If you choose to syndicate your ads, your prospects who use Gmail may see them if the text of the e-mail is deemed relevant to your offer. For example, Figure 1-5 shows an e-mail that I (almost) sent to the MacArthur Foundation, humbly explaining why I should receive one of their "genius grants." To the right, you can see ads for small business grants, a Cow Ringtone, triggered by my mention of a self-esteem program for cows, and two resources for college grant-seekers.

Google rose from nothing to become the world's most popular search engine in just a few months because it did one thing faster and better than all the rest: help Internet searchers find what they were looking for. I don't want to overload you with the details of Google's search algorithm (especially because it's such a secret that if I told you, I'd have to kill you, and I would have to understand words like eigenvector and stochastic in order to explain it), but you will become a better Google advertiser when you get the basic principles. The most important word in Google's universe is relevance.

Note

When you type a word or phrase into Google, the search engine asks the World Wide Web for the best page to show you. The big innovations Google uses are a couple of calculations: One, called PageRank, is basically a measure of the popularity of a particular page, based on how many other Web pages link to that page and how popular those pages are. (Sort of like high school — the definition of a popular kid is one who is friends with other popular kids.) The other calculation is known as Page Reputation, which answers the question, "Okay, this page may be popular, but for which topic?" The Page Reputation of a Web page determines whether it will appear in a given search; the PageRank determines whether it will be the first listing, the third, or the four million and eleventh.

The entire Google empire is based on this ability to match the right Web pages, in the right priority order, with a given search phrase. The day Google starts showing irrelevant results is the day after you should have sold all your Google stock.

When Google started, it only showed the results of its own calculations. These results are known as organic listings. Organic listings appear on the left side of the Google results page (see Figure 1-6, which includes organic listings only and no AdWords entries).

In the early days of AdWords, your ad was shown based on a combination of two numbers: your bid price, or how much you were willing to pay for a click (that is, someone clicking your ad and visiting your Web page), and a very important metric called Click-Through Rate (CTR), which is the percentage of searchers who click your ad after seeing it. Now, Google also takes into account the quality of the fit between the ad and your Web site. If searchers exit your site so fast that they leave skid marks, Google figures that they didn't find what they were looking for, and you're penalized for irrelevance.

AdWords is a PPC (pay per click) advertising medium. Unlike other forms of advertising, with PPC you pay only for results: live visitors to your Web site.

AdWords allows you as the advertiser to decide how much you're willing to pay for a visitor searching on a given keyword. For example, if you sell vintage sports trading cards, you can bid more for Babe Ruth rookie card than John Gochnaur card if you can make more money selling the Babe Ruth card.

For many businesses, advertising is like a slot machine: You put in your money, pull the handle, and see what happens. Sometimes you do well; sometimes you don't. Either way, you don't learn much that will help you predict the results of your next pull. PPC has changed all that for businesses with the patience and discipline to track online metrics. Just as a gumball machine reliably gives you a gumball every time you drop a quarter, PPC can reliably deliver a customer to your Web site for a predictable amount of money. Once you run your numbers (explained in Part V), you know exactly how much, on average, a visitor is worth from a particular keyword. You may find that you make $70 in profit for every 100 visitors from AdWords who searched for biodegradable wedding dress. Therefore, you can spend up to $0.70 for each click from this keyword and still break even or better on the first sale.

Direct marketing differs from "brand" marketing, the kind we're used to on TV and radio and newspapers, in several important ways. AdWords represents direct marketing at its purest, so it's important to forget everything you thought you knew about advertising before throwing money at Google.

Direct marketers set one goal for their ads: to compel a measurable response in their prospects. Unlike brand marketers, you won't spend money to give people warm and fuzzy feelings when they think about your furniture coasters or ring-tones or South Carolina resort rentals. Instead, you run your ad to get hot prospects to your Web site. On the landing page (the first page your prospect sees after leaving Google), you direct your prospect to take some other measurable action — fill out a form, call a phone number, initiate a live chat, drop everything, race to the airport and hop on the first plane to Hilton Head, and so on.

On the Web, you can track each visitor from the AdWords click through each intermediate step straight through to the first sale and all subsequent sales. So at each step of the sales cycle, on each Web page, in each e-mail, with each ad, you ask your prospect to take a specific action right now.

Brand advertisers rarely have the luxury of asking for immediate action. The company that advertises home gyms during reruns of Gilligan's Island has no illusion that 8,000 viewers are going to TiVO the rest of the episode and drive, tires squealing, to the nearest fitness store to purchase the GalactiMuscle 5000. They count on repetition to eventually lead to sales.

Contrast that approach with infomercials, which have one goal: to get you to pick up the phone NOW because they realize that once you get distracted, they've lost their chance of selling to you.

The Internet outdoes the immediacy and convenience of the infomercial by maintaining the same channel of communication. Instead of jumping from TV to phone, AdWords and your Web site function together as a seamless information-gathering experience.

Because your prospects are doing what you want them to do (or not), you can measure the effectiveness of each call to action. For example, say you sell juggling equipment to left-handed people. You show your ad to 30,000 people in one week. Your ad attracts 450 prospects to your Web site, at an average CPC of $0.40. Your landing page offers a 5% off coupon in exchange for a valid e-mail address, and by the end of the week, your mailing list has 90 leads — 20% of all visitors. You follow up with an e-mail offer that compels 10 sales totaling $600.00.

The following table shows an example of an AdWords ad campaign's overall metrics.

Metric | Total cost or percentage |

|---|---|

Total advertising cost | $180 (450 × $0.40) |

Sales total | $600 |

333% ($600 ÷ $180) | |

AdWords ad CTR | 1.5% (450 ÷ 30,000) |

Landing page lead conversion | 20% (90 ÷ 450) |

E-mail sales conversion | 11% (10 ÷ 90) |

Cost per visitor | $0.40 |

Average visitor value | $1.33 ($600 ÷ 450) |

Cost per lead | $2.00 ($180 ÷ 90) |

Average value of a lead | $6.67 ($600 ÷ 90) |

Cost per sale | $18.00 ($180 ÷ 10) |

Average value of a sale | $60 ($600 ÷ 10) |

What does this horrific flashback to SAT prep mean to your business? These numbers give you control over your advertising spending, allow you to predict cash flow (just play a game of Monopoly with my daughter if you don't appreciate the value of positive cash flow!), and enable you to assess additional market opportunities by comparing them to this pipeline. (If you're not rubbing your hands together and going, "Muahahaha" like a cartoon villain, I still have some explaining to do.)

In this hypothetical case, you have found a gumball machine that gives you $1.33 every time you drop 40 cents into the machine. You've set it up once, and it happens automatically as long as Google likes your credit card. ROI is a metric that simply converts your input amount to a single dollar, so you can easily compare ROI for different campaigns and markets. ROI answers the question, if you put a dollar into this machine, how much comes out? ROI of 333% means that you get $3.33 out for every dollar you put in. If you found a gumball machine that managed that trick, you'd never go back to slot machines again.

Now suppose the market becomes more competitive, and your CPC rises. If you were advertising in your local newspaper and the ad rep told you that prices were going up by 25 percent, what would you do? Would you keep advertising at the same level, cut back, or stop showing your ads in that paper completely? Unless you're measuring the ROI of your ads, you have no way to make a rational decision.

Say your AdWords CPC from the example shown in the preceding table increases by 25 percent. Now your cost per visitor is 50 cents. Do you keep advertising? Of course — you're still paying less for a lead than the value of that lead — 83 cents less. Your ROI is down from 333% to a still respectable 267% (total advertising cost is now 450 × $0.50 = $225, and $600 ÷ $225 = 267%).

But wait — there's more! (Did I mention how much I enjoy a good infomercial?) AdWords makes it simple not only to see your metrics but also to improve your profitability by conducting tests. The ability to test different elements of your sales process is the next important element of direct marketing.

So far in this chapter, I've only discussed inputs (how much you pay to advertise and how many Web site visitors) and outputs (how much you receive in sales). But it's really the intermediate metrics (called throughputs by people like me who sometimes find it useful to pretend we went to business school) that give us an opportunity to make huge improvements in our profitability.

For example, imagine you improve the CTR of your ad from 1.5% to 2.2% without lowering the quality of your leads. Big whoop, right? An improvement of 0.7% — who cares? Actually, it's an improvement of 68% — for the same $180 advertising spend, you now get 660 visitors instead of 450. If everything else stays the same, your visitor value of $1.33 means your sales increase to $880, for an ROI of 489%.

But wait — there's more! What's to stop you from improving your landing page by 20 percent by testing different versions? Instead of getting 20 leads out of 100, you're now collecting 24. Six hundred sixty visitors now translate into 158 leads. If 11 percent of them make a purchase from your e-mail offer, that's 17 sales. At an average of $60 per sale, you've now made $1,020.

But wait — there's more! How about testing your e-mail offer too? Let's say you get a 36 percent improvement, and now 15 percent of e-mail recipients make a $60 purchase. That's 23 sales at $60, for a new total of $1,380.

Thanks to the miracle of compounding, the three improvements (68% × 20% × 36%) give you a total improvement of 230%. This isn't pie-in-the-sky math, either — when you test the elements of your sales process scientifically, it's hard not to make significant improvements. See Chapter 13 for the stunningly simple explanation of how to do it. And Chapter 14 shows you how to consistently improve the ability of your Web site to turn visitors into paying customers.

In case you got a little lost in the numbers in the previous section, I want to make sure you got the moral of that direct marketing story: It's a process of multiple steps. Seth Godin (marketing guru and author) compares direct marketing to dating. You wouldn't walk up to a stranger in a museum and propose marriage. (If you did, and you're happily married 17 years later, please don't take offense; I'm not talking about you.) In fact, there are a lot of things you wouldn't suggest to a stranger in a museum that you might very well suggest to someone who knew you a little better. (If you're not sure what these are, check out Dr. Ruth's contribution to the For Dummies series.)

Direct marketing operates on the premise that you have to earn your prospects' trust before they become your customers. As with dating, you demonstrate your trustworthiness and likeability by asking for small commitments with low-downside risk. Your ad, the first step in the AdWords dating game, makes a promise of some sort while posing no risk. Your visitor can click away from your Web site with no hassle or hard feelings. AdWords' Editorial Guidelines commit you to playing nice on your landing page: an accurate display URL, no pop-ups, and a working Back button so your visitors can hightail it back to their search results if they don't like your site.

Your landing page makes a second offer that involves getting permission from your prospects to communicate with them. Here's the deal you're offering: "I'll give you something of value if you let me contact you. And any time you want me to stop contacting you, just let me know and I'll stop. And I'll never share your contact information with anybody else who might try to contact you."

Sometimes you can go right for the sale on the landing page, and sometimes it's better to focus on turning your visitor into a lead — someone with whom you can follow up later. Chapter 10 offers guidelines for creating an effective landing page.

When your prospect gets to know you and trusts you, you increase the value you provide while asking for larger and larger commitments. Depending on your business, your sales/dating process could consist of surveys, reports, free samples, try-before-you-buy promotions, teleseminars, e-mails, live chat, software downloads, and more. When you ask for the sale, you in effect, are proposing marriage — or a long-term relationship, anyway.

Direct marketing focuses on prospects — people who raise their hands and tell you they're interested in what you have. When folks click your AdWords ad, they've just identified themselves to you as someone worth developing a relationship with. Returning to the dating analogy, this is like a stranger smiling at you at the museum. You respond by striking up a conversation about the artwork you're both looking at ("Do you think the green splotch in the upper-left-hand corner represents a rebirth of hope or an exploding drummer?") If the two of you hit it off, you don't want to leave the building without getting a phone number.

In dating, the phone number is the litmus test of interest. If you can't get the phone number, or if you call it and discover you've really been given the number for the West Orange Morgue (now why are you assuming that actually happened to me?), you know that relationship has no future.

Your prospect has the online attention span of a guppy. When we go online, we typically multitask, we have multiple windows open, we're checking e-mail, IMing, watching videos, listening to MP3s, and searching and browsing and surfing. Not to mention answering the phone, opening the mail, eating and drinking, and dealing with other people. How many times have you visited a Web page, been distracted, and never found it again? How many times have you bookmarked a Web page, intending to visit again, and haven't gotten around to it?

Get the prospect's e-mail address as soon as you can. Before they get distracted. Before they browse back to Google and click one of your competitors' ads. Before they spill a cappuccino latte all over the keyboard.

With their e-mail address and permission to follow up, you've done all you can to inoculate yourself from the short Internet attention span. You now have a chance of continuing the conversation until it leads to a sale.

I began this chapter with a pathetic rant about my experiences as a Yellow Pages advertiser. Now let's look at the Yellow Pages from the point of view of the user — the person searching for a solution to a problem. But I'm done whining, so I'm not going to complain about figuring out which heading to look under, deciding which listing to call, dealing with voice mail (no, really, I'm done whining). Instead, imagine a totally new experience: the Magic Yellow Pages.

In the Magic Yellow Pages, you don't have to flip through hundreds of pages. In fact, the book doesn't have any pages — just a blank cover. You write down what you're looking for on the cover, and then — Poof! — the listings appear. The most relevant listings, according to the Magic Yellow Pages, appear on the cover. Subsequent pages contain more listings, in order of decreasing relevance.

But wait — there's more! The listings in the Magic Yellow Pages don't have phone numbers. Instead, touch the listing and you're magically transported to the business itself. Don't like what you see? Snap your fingers and you're back in front of the Magic Yellow Pages, ready to touch another listing or type another query.

This is how AdWords functions from the point of view of your prospects: They have all the power. They conjure entire shopping centers full of competing shops by typing words — and they window-shop until they find what they want or give up.

Their search term represents an itch that they want to scratch at that very moment — some unsolved problem. They are looking for the shortest distance between their itch and a good scratch. Maybe they want information. Maybe they want a product. Maybe they want to be entertained. Maybe they want to be told that their problem isn't so bad.

It's your job to figure out what they really want (based on the keyword they type) and give it to them quicker and more obviously than your competitors. In the Magic Yellow Pages, the rules are, "Give the prospect what she wants and nobody gets hurt." Winning the game of AdWords comes down to figuring out what your prospect — the person you can help — is thinking and feeling as they type their search. When you understand this, you bid on the right keywords, you show compelling ads, and you present clear and irresistible offers on your Web site. See Chapter 4 to discover how to conduct quick and easy keyword research, so you can become the champion itch-scratcher in your market.