Chapter 7

Ten Simple Security Searches That Work

Abstract

This chapter covers ten simple security searches that work.

Keywords

site

intitle:index.of

error

warning

login

logon

username

userid

employee.ID

“your username is”

password

passcode

“your password is”

admin

administrator

–ext:html

–ext: htm

–ext:shtml

–ext:asp

–ext:php

inurl:temp

inurl.tmp

inurl:backup

inurl:bak

intranet

help.desk

Introduction

Although we see literally hundreds of Google searches throughout this book, sometimes it’s nice to know there are a few searches that give good results just about every time. In the context of security work, we’ll take a look at 10 searches that work fairly well during a security assessment, especially when combined with the site operator, which secures the first position in our list. As you become more and more comfortable with Google, you’ll certainly add to this list, modifying a few searches and quite possibly deleting a few, but the searches here should serve as a very nice baseline for your own top 10 list. Without further ado, let’s dig into some queries.

site

The site operator is absolutely invaluable during the information-gathering phase of an assessment. Combined with a host or domain name, this query presents results that can be overwhelming, to say the least. However, the site operator is meant to be used as a base search, not necessarily as a standalone search. Sure, it’s possible (and not entirely discouraged) to scan through every single page of results from this query, but in most cases it’s just downright impractical.

Important information can be gained from a straight-up site search, however. First, remember that Google lists the results in page-ranked order. In other words, the most popular pages float to the top. This means you can get a quick idea about what the rest of the Internet thinks is most worthwhile about a site. The implications of this information are varied, but at a basic level you can at least get an idea of the public image or consensus about an online presence by looking at what floats to the top. Outside the specific site search itself, it can be helpful to read into the context of links originating from other sites. If a link’s text says something to the effect of “CompanyXYZ s***s!”, there’s a good chance that someone is discontent about CompanyXYZ.

As we saw in Chapter 5, the site search can also be used to gather information about the servers and hosts that a target maintains. Using simple reduction techniques, we can quickly get an idea about a target’s online presence. Consider the simple example of site: nytimes.com –site: www.nytimes.com shown in Figure 7.1.

Figure 7.1

This query effectively locates hosts on the nytimes.com domain other than www.nytimes.com. Just from a first pass, Figure 7.1 shows three hosts: theater.nytimes.com, www2.nytimes.com, salary.nytimes.com and realestate.nytimes.com. These may be hosts, or they may be subdomains. Further investigation would be required to determine this. Also remember to validate your Google results before unleashing your megascanner of choice.

intitle:index.of

intitle:index.of is the universal search for directory listings. Directory listings are chock-full of juicy details, as we saw in Chapter 3. Firing an intitle:index.of query against a target is fast and easy and could produce a killer payoff.

error | warning

As we’ve seen throughout this book, error messages can reveal a great deal of information about a target. Often overlooked, error messages can provide insight into the application or operating system software a target is running, the architecture of the network the target is on, information about users on the system, and much more. Not only are error messages informative, they are prolific. This query will take some playing with, and is best when combined with a site query. For example, a query of (“for more information” | “not found”) (error | warning) returns interesting results, as shown in Figure 7.2.

Figure 7.2

Unfortunately, some error messages don’t actually display the word error, as shown in the SQL located with a query of “access denied for user”“using password” shown in Figure 7.3.

Figure 7.3

This error page reveals usernames, filenames, path information, IP addresses, and line numbers, yet the word error does not occur anywhere on the page. Nearly as prolific as error messages, warning messages can be generated from application programs. In some cases, however, the word warning is specifically written into the text of a page to alert the Web user that something important has happened or is about to happen. Regardless of how they are generated, pages containing these words may be of interest during an assessment, as long as you don’t mind teasing out the results a bit.

login | logon

As we’ll see in Chapter 8, a login portal is a “front door” to a Web site. Login portals can reveal the software and operating system of a target, and in many cases “self-help” documentation is linked from the main page of a login portal. These documents are designed to assist users who run into problems during the login process. Whether the user has forgotten a password or even a username, this documents can provide clues that might help an attacker, or in our case a security tester, gain access to the site.

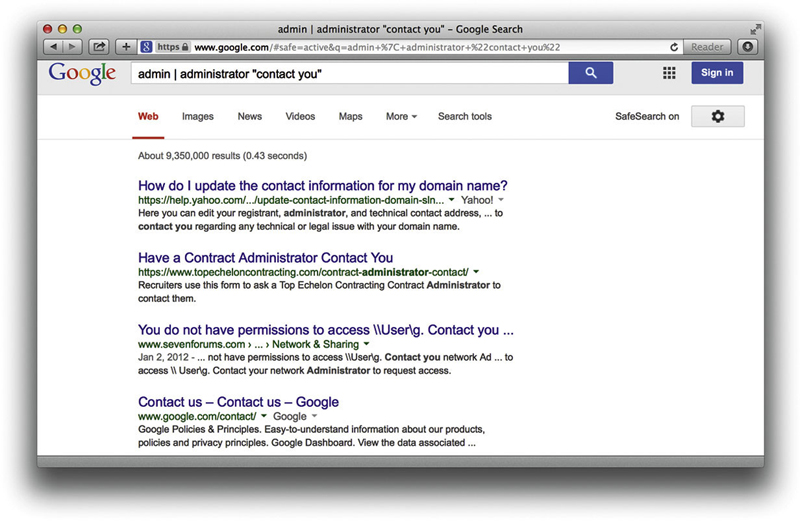

Many times, documentation linked from login portals lists email addresses, phone numbers, or URLs of human assistants who can help a troubled user regain lost access. These assistants, or help desk operators, are perfect targets for a social engineering attack. Even the smallest security testing team should not be without a social engineering whiz that could talk an Eskimo out of his thermal underwear. The vast majority of all security systems have one common weakest link: a human behind a keyboard. The words login and logon are widely used on the Internet, occurring on millions of pages, as shown in Figure 7.4.

Figure 7.4

Also common is the phrase login trouble in the text of the page. A phrase like this is designed to steer wayward users who have forgotten their login credentials. This information is of course very valuable to attackers and pen testers alike.

username | userid | employee.ID “your username is”

As we’ll see in Chapter 9, there are many different ways to obtain a username from a target system. Even though a username is the less important half of most authentication mechanisms, it should at least be marginally protected from outsiders. Figure 7.5 shows that even sites that reveal very little information in the face of a barrage of probing Google queries, return many potentially interesting results to this query. To avoid implying anything negative about the target used in this example, some details of the Figure 7.5 have been edited.

Figure 7.5

The mere existence of the word username in a result is not indicative of a vulnerability, but results from this query provide a starting point for an attacker. Since there’s no good reason to remove derivations of the word username from a site you protect, why not rely on this common set of words to at least get a foothold during an assessment?

password | passcode | “your password is”

The word password is so common on the Internet, there are over a billion results for this one-word query. Launching a query for derivations of this word makes little sense unless you actually combine that search with the site operator.

During an assessment, it’s very likely that results for this query combined with a site operator will include pages that provide help to users who have forgotten their passwords. In some cases, this query will locate pages that provide policy information about the creation of a password. This type of information can be used in an intelligent-guessing or even a brute-force campaign against a password field.

Despite how this query looks, it’s quite uncommon for this type of query to return actual passwords. Passwords do exist on the Web, but this query isn’t well suited for locating them. (We’ll look at queries to locate passwords in Chapter 9.) Like the login portal and username queries, this query can provide an informational foothold into a system. Most often, this query should be used alongside a site operator, but with a little tweaking, the query can be used without site to illustrate the point, as shown in Figure 7.6. “Forgotten password” pages like these can be very informative.

Figure 7.6

admin | administrator

The word administrator is often used to describe the person in control of a network or system. There are so many references to the word on the Web that a query for admin | administrator weighs in at half a billion results. This suggests that these words have most likely been referred to on a site that you’re assessing. However, the value of these and other words in a query does not lie in the number of results but in the contextual relevance of the words. Tweaking this query, with the addition of “change your” can return interesting results, even without the addition of a site operator, as shown in Figure 7.7.

Figure 7.7

The phrase Contact your system administrator is a fairly common phrase on the Web, as are several basic derivations. A query such as “please contact your * administrator” will return results that refer to local, company, site, department, server, system, network, database, email, and even tennis administrators. If a Web user is told to contact an administrator, odds are that there’s data of at least moderate importance to a security tester.

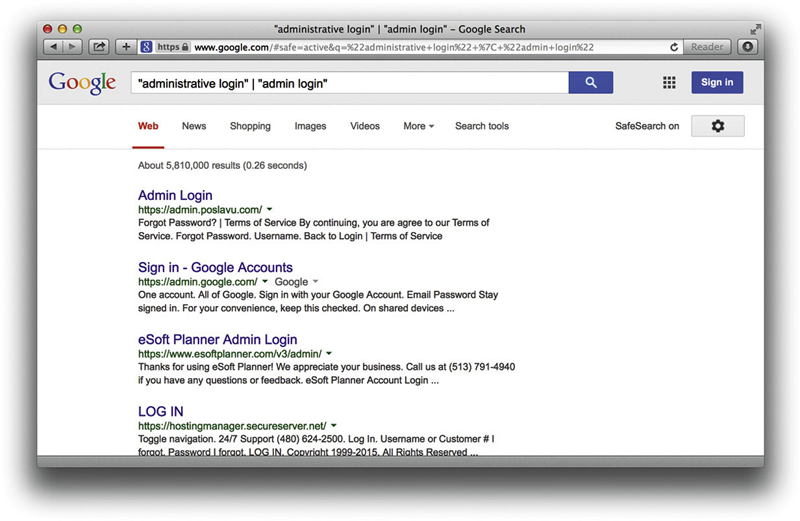

The word administrator can also be used to locate administrative login pages, or login portals. (We’ll take a closer look at login portal detection in Chapter 8.) A query for “administrative login” returns millions of results, many of which are administrative login pages. A security tester can profile Web servers using seemingly insignificant clues found on these types of login pages. Most login portals provide clues to an attacker about what software is in use on the server and act as a magnet, drawing attackers who are armed with an exploit for that particular type of software. As shown in Figure 7.8, many of the results for the combined admin query reveal administrative login pages.

Figure 7.8

Another interesting use of the administrator derivations is to search for them in the URL of a page using an inurl search. If the word admin is found in the hostname, a directory name, or a filename within a URL, there’s a decent chance that the URL has some administrative function, making it interesting from a security standpoint.

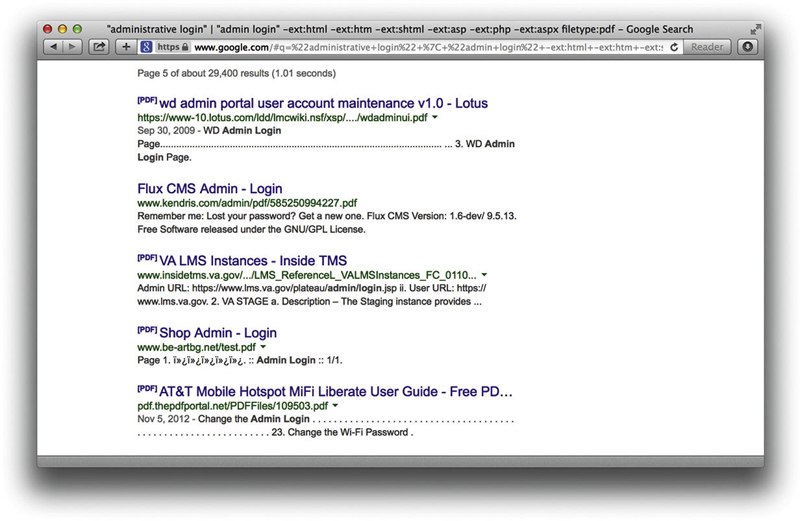

–ext:html –ext:htm –ext:shtml –ext:asp –ext:php

The –ext:html –ext:htm –ext:shtml –ext:asp –ext:php query uses ext, a synonym for the filetype operator, and is a negative query. It returns no results when used alone and should be combined with a site operator to work properly. The idea behind this query is to exclude some of the most common Internet file types in an attempt to find files that might be more interesting for our purposes.

As you’ll see through this book, there are certainly lots of HTML, PHP, and ASP pages that reveal interesting information, but this chapter is about cutting to the chase, and that’s what this query attempts to do. The documents returned by this search often have great potential for document grinding, which we’ll explore in more detail in Chapter 10. The file extensions used in this search were selected very carefully. First, www.filext.com (one of the Internet’s best resources for all known file extensions) was consulted to obtain a list of every known file extension. Each entry in the list of over 8000 file extensions was converted into a Google query using the filetype operator. For example, if we wanted to search for the PDF extension, we might use a query like filetype:PDF to get the number of known results on the Internet. This type of Google query was performed for each and every known file extension from filext.com, which can take quite some time, especially when done in accordance with Google Terms of Use agreement. Once the results were gathered, they were sorted in descending order by the number of hits.

A site search combined with a negative search for the top ten most common file types can lead you right to some potentially interesting documents. In some cases, this query will need to be refined, especially if the site uses a less common server-generated file extension. For example, consider this query combined with a site operator, as shown in Figure 7.9. (To protect the identity of the target, certain portions of the Figure 7.9 have been edited.)

Figure 7.9

As revealed in the search results, this site uses the ASPX extension for some Web content. By adding –ext:aspx to the query and resubmitting it, that type of content is removed from the search results. This modified search reveals some interesting information, as shown in Figure 7.10.

Figure 7.10

By adding a common file extension used on this site, after a few pages of mediocre results we discover a page full of interesting information. Result line 1 reveals that the site supports the HTTPS protocol, a secured version of HTTP used to protect sensitive information. The mere existence of the HTTPS protocol often indicates that this server houses something worth protecting. Result line 1 also reveals several nested subdirectories (/research/files/summaries) that could be explored or traversed to locate other information. This same line also reveals the existence of a PDF document dated the first quarter of 2003.

Result line 2 reveals the existence of what is most likely a development server named DEV. This server also contains subdirectories (/events/archives/strategiesNAM2003) that could be traversed to uncover more information. One of the subdirectory names, strategiesNAM2003, contains a “the string 2003,” most likely a reference to the year 2003. Using the incremental substitution technique discussed in Chapter 3, it’s possible to modify the year in this directory name to uncover similarly named directories. Result line 2 also reveals the existence of an attendee list that could be used to discover usernames, email addresses, and so on.

Result line 3 reveals another machine name, JOBS, which contains a ColdFusion application that accepts parameters. Depending on the nature and security of this application, an attack based on user input might be possible. Result line 4 reveals new directory names, /help/emp, which could be traversed or fed into other third-party assessment applications.

The results continue, but the point is that once common, purposefully placed files are removed from a search, interesting information tends to float to the top. This type of reduction can save an attacker or a security technician a good deal of time in assessing a target.

inurl:temp | inurl:tmp | inurl:backup | inurl.bak

The inurl:temp | inurl:tmp | inurl:backup | inurl:bak query, combined with the site operator, searches for temporary or backup files or directories on a server. Although there are many possible-naming conventions for temporary or backup files, this search focuses on the most common terms. Since this search uses the inurl operator, it will also locate files that contain these terms as file extensions, such as index.html.bak, for example. Modifying this search to focus on file extensions is one option, but these terms are more interesting if found in a URL.

intranet | help.desk

The term intranet, despite more specific technical meanings, has become a generic term that describes a network confined to a small group. In most cases the term intranet describes a closed or private network, unavailable to the general public. However, many sites have configured portals that allow access to an intranet from the Internet, bringing this typically closed network one step closer to potential attackers.

In rare cases, private intranets have been discovered on the public Internet due to a network device misconfiguration. In these cases, network administrators were completely unaware that their private networks were accessible to anyone via the Internet. Most often, an Internet-connected intranet is only partially accessible from the outside. In these cases, filters are employed that only allow access to certain pages from specific addresses, presumably inside a facility or campus. There are two major problems with this type of configuration. First, it’s an administrative nightmare to keep track of the access rights of specific pages. Second, this is not true access control. This type of restriction can be bypassed very easily if an attacker gains access to a local proxy server, bounces a request off a local misconfigured Web server, or simply compromises a machine on the same network as trusted intranet users. Unfortunately, it’s nearly impossible to provide a responsible example of this technique in action. Each example we considered for this section was too easy for an attacker to reconstruct with a few simple Google queries.

Help desks have a bad reputation of being, well, too helpful. Since the inception of help desks, hackers have been donning alternate personalities in an attempt to gain sensitive information from unsuspecting technicians. Recently, help desk procedures have started to address the hacker threat by insisting that technicians validate callers before attempting to assist them. Most help desk workers will (or should) ask for identifying information such as usernames, Social Security numbers, employee numbers, and even PIN numbers to properly validate callers’ identities. Some procedures are better than others, but for the most part, today’s help desk technicians are at least aware of the potential threat that is posed by an imposter.

In Chapter 4, we discussed ways Google can be used to harvest the identification information a help desk may require, but the intranet | help.desk query is not designed to bypass help desk procedures but rather to locate pages describing help desk procedures. When this query is combined with a site search, the results could indicate the location of a help desk (Web page, telephone number, or the like), the information that might be requested by help desk technicians (which an attacker could gather before calling), and in many cases links that describe troubleshooting procedures. Self-help documentation is often rather verbose, and a crafty attacker can use the information in these documents to profile a target network or server. There are exceptions to every rule, but odds are that this query, combined with the site operator, will dig up information about a target that can feed a future attack.

Summary

This list may not be perfect, but these 10 searches should serve you well as you seek to compile your own list of killer searches. It’s important to realize that a search that works against one target might not work well against other targets. Keep track of the searches that work for you, and try to reach some common ground about what works and what doesn’t. Automated tools, discussed in Chapters 11 and 12, can be used to feed longer lists of Google queries such as those found in the Google Hacking Database, but in some cases, simpler might be better. If you’re having trouble finding common ground in some queries that work for you, don’t hesitate to keep them in a list for use in one of the automated tools that we’ll discuss later.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.