“Know thyself.” | ||

| --The Seven Sages Inscription at the Delphic Oracle | ||

The assessment of strengths and development needs described in Chapter 7 produces a great deal of data. Frequently, the meaning and value of these data won’t be readily apparent to Acceleration Pool members. So, before they can target any development activities, members must have a firm grasp of what these data are telling them. That is, they must form a solid understanding of the areas in which they have strengths and those that they need to develop, as well as how their development efforts should be prioritized.

To put their assessment results to work, pool members must accomplish six tasks:

Understand the organization’s executive descriptors (in the four categories of job challenges, organizational knowledge, competencies, and executive derailers) and why they are important to the target organizational level.

Understand the findings from the assessment activities as they relate to the executive descriptors.

Consider how the assessment results relate to past feedback from 360° instruments, performance appraisal discussions, and comments from friends, family, and coworkers.

Develop a list of strengths and development needs in each of the four executive descriptor categories.

Recognize how the executive descriptor data fit together. For example, an individual needs to know how his or her competencies and derailers have related to one another in the past and how they might relate at higher-level positions. Also, there often is a relationship among different areas of development need that must be considered in development planning. For example, a person might be weak in the competency Entrepreneurship and also lack exposure to the organization’s marketing activities, a knowledge area. In such situations it would be efficient to work on developing both at the same time.

Prioritize development needs in each of the four executive descriptor categories.

These six tasks might sound simple enough, but getting through them actually presents a major hurdle for pool members; in most cases they will need some help. Because the person giving the Acceleration Center feedback (competencies and derailers) often does not know enough about the organization to accurately evaluate the company-oriented descriptors, many organizations divide the discussion of descriptors into two parts: 1) the “personal” arena of competencies and derailers, and 2) the “company-oriented” descriptors of job challenges and organizational knowledge. One professional usually works with the pool member on the first area, while another professional or a member of the Executive Resource Board focuses on the second. However, one professional can cover all four descriptor areas if qualified to do so.

Note

![]() denotes that information on this topic is available at the Grow Your Own Leaders web site (www.ddiworld.com/growyourownleaders).

denotes that information on this topic is available at the Grow Your Own Leaders web site (www.ddiworld.com/growyourownleaders).

Many rising leaders have strong opinions about how to succeed in business and can be reluctant to accept the notion that they have development needs. Their egos and successful track records can also stand in the way of making a personal commitment to change.

The key to overcoming those roadblocks is to provide feedback from an honest, credible source. The best source that we know of is an Acceleration Center professional. The professional can help pool members understand their behaviors relative to the organization’s competencies and derailers, and integrate behavioral observations and indications with personal attributes that have been determined by a variety of self-report instruments (see Chapter 7). Pool members need to see how competencies and derailers interact; that is, being strong in one competency (e.g., Decisiveness) can magnify the impact of another (e.g., Low Judgment). Also, the professional can help pool members integrate information from 360° feedback and other sources to provide holistic insights that are compelling and challenging.

Acceleration Center professionals who provide feedback about competencies and derailers do so through high-level themes that pull together certain competencies and derailers. They cite specific behavioral examples of what the individual said or did in the simulations to support their observations.

Acceleration Pool members often will have multiple-perspective data from previous jobs or applications in their current organization. Multirater (360°) instruments are so prevalent today that it’s not unusual for a pool member to have data from four or five of them. Pool members should be encouraged to bring in that information for their discussion of strengths and development needs. At the very least they should be prompted to recall the results of previous 360° instruments when considering their current data. It’s also a good idea for pool members to bring performance appraisals or other performance-related forms to the discussion because they can be helpful in identifying behavioral trends or issues.

The more sources of available information, the better pool members will be able to understand their situation and pinpoint the implications of their data. For example, an Acceleration Center found one person to be weak in planning, although 360° data indicated that she had no problem in this area. During the discussion with the assessment professional, the pool member explained that her direct reports respected her planning skills because she delegated almost all the planning tasks. This insight explained the apparent disparity and confirmed the Acceleration Center’s judgment that the pool member was strong in delegation. It also prompted the pool member to think about how her deficiencies in planning skills might affect her performance at higher organizational levels.

In another situation the Acceleration Center evaluated a manager as adequate in judgment, while his direct reports rated him as weak. Discussions revealed that the Acceleration Center had focused primarily on financial and other data-driven judgments, which were, in fact, a strength. In areas concerning the deployment of people, the Acceleration Center found his judgment to be average at best. Obviously, this was the aspect of judgment being rated by his direct reports in the 360° survey.

Overall, the discussion of competencies and derailers usually lasts several hours, including time for the final prioritization of strengths and development needs. Discussions should be held face-to-face if possible; a videoconference is usually the next best alternative. A phone conference is the least desirable option, but it can be effective if the pool member receives an Acceleration Center report and discussion questions in advance.

When an Acceleration Center professional is not available, other people can help pool members integrate data and prioritize development needs. These people include:

An executive coach. A coach must understand the pool member’s competency and derailer development priorities and the thinking behind prioritizing them; therefore, it would be sensible and efficient to pair the coach with his or her charge when needs are being identified and prioritized. To provide professional-level feedback, the coach must be trained in how the Acceleration Center operates.

A psychologist. When an Acceleration Center is not used, some organizations use a psychologist to administer tests and interview pool members to identify enablers and derailers. When psychologists are used for this purpose, they should give their interpretive feedback directly to the pool members and help them to prioritize derailers.

An HR specialist. This could be someone within the organization who specializes in executive development or succession management.

Providing feedback about Acceleration Center results can be a very intimidating task because of the personal impact that such data can have and because the people receiving the feedback are such high-powered individuals.

For example, not long ago a highly regarded executive (a member of the chairman’s committee) at a major automotive manufacturer participated in an in-depth Acceleration Center assessment. This executive received a descriptive report in preparation for a coaching session with an assessor, one of the authors of this book. Upon arriving at the session, the assessor was met with a gruff greeting and escorted to a large conference table. The executive began by dropping his assessment report onto the table with a resounding slap and taking a seat—hands behind his head, feet up on the polished mahogany table. Obviously annoyed, he said, “I just want you to know right now that I ain’t changin’ one damn iota based on this stuff.”

The “feedback and coaching” session that followed took on a life of its own, but not the planned one. A series of questions and answers confirmed the assessment results, which identified profound strengths as well as equally profound development needs. But the conversation quickly moved away from diagnosis and into the fundamental value of assessment and diagnosis. “Why even do this?” the executive asked, as he insisted that change was neither necessary nor possible.

Still, there were the assessment results, which the executive wholeheartedly acknowledged as accurate—and amusing. He was characterized by intense volatility, impatience, and work practices that, at times, bordered on the despotic. Ironically, he was regarded as one of the most inspirational and visionary leaders in the organization’s history. He was feared and loathed by some, yet loved and revered by others. This bipolar persona required reconciliation. He explained that passion, love of the business, insistence on high performance, and the desire to win were behind his behavior. His pride in success and in having survived many corporate catastrophes led him to conclude that his style worked.

However, the conversation took a different turn when the auto executive was asked whether he would recommend his style to emerging leaders in the organization. Although he had quickly touted his style’s merits in his own case, he said that he regarded its proliferation in the organization as a potential poison. Slowly, after many probing questions about the relationship of his style and the emerging leadership trends within the organization, he began to articulate a different opinion about his willingness to act on the assessment results. He ultimately acknowledged responsibility for making his organization aware that his style was generally ineffective in today’s leadership environment. He also conceded that he would be unlikely to succeed with this style if he were starting his career today. In the end the executive pointed out—accurately—that the power of the assessment process was not in the diagnosis, but in the discussion of the diagnosis.

This example underscores a lesson that we have learned through years of providing feedback to thousands of executives worldwide. Even the most accurate, comprehensive assessment will be meaningless unless the person being assessed recognizes the accuracy and value of the data and accepts the diagnosed strengths and development needs. One of the main advantages of using simulations in Acceleration Centers is the availability of specific observations and descriptions of actions. Those observed behavioral data—coupled with other behavioral data from the background interview and multiple-perspective (360°) instruments and augmented by interpretive insights from self-report instruments—are usually enough to convince people about what they need to emphasize and what they need to change. Usually—but not always.

When a doubting individual needs to be further convinced that he or she needs development (or when there is a need to check the accuracy of a diagnosis), an organization has several alternatives:

Multirater (360°) instruments. If the competency or derailer can be observed in the person’s current job, 360° feedback from direct reports, peers, and managers can add persuasive information.

Live multirater (360°) interviews. These can be even more persuasive because they provide behavioral examples gathered in interviews with appropriate peers or direct reports. They are particularly effective in obtaining targeted data to convince individuals already in or near the executive level.

An assignment in which the competency or derailer can be observed and appropriate feedback provided. This provides a real-world setting in which the person is challenged to show that the diagnosed problem does not exist.

An additional assessment center experience focusing on self-awareness in the competency or derailer being discussed. The Center for Creative Leadership and other organizations offer public self-awareness assessment centers that can provide a second opinion about many competencies and derailers.

Attendance at a training program that provides self-insights as well as skill development. For example, several organizations use a training program, titled Strategic Leadership ExperienceSM, that involves a four-day, computer-based business simulation. Participants are required to display a number of competencies related to nine strategic leadership roles and then receive feedback on them. They also receive feedback on derailers. (See Chapter 12 for a description of this program.)

Compared to dealing with the more personal issues of competencies and derailers, it is relatively easy to diagnose and prioritize development needs in the areas of job challenges and organizational knowledge. Most Acceleration Pool members have fairly accurate insights about what they know and what they need to learn, and they are less sensitive about admitting that they have things to learn in these areas. However, to ensure accurate ratings, the person counseling the pool member should closely review the self-report data provided on the development targets and ask questions about any job or organizational insights gained, any skills developed, and the person’s ease (or difficulty) of learning new skills and adapting to the new situation. For example, a pool member who reports experience in a new plant start-up might have been only peripherally involved in the effort and, therefore, learned relatively little about the trials and tribulations that it involved. A few questions can usually prompt realistic self-evaluations of such experiences.

The HR representative who works with the Executive Resource Board usually discusses job challenges and organizational knowledge with pool members. The representative will understand the board’s standards relative to the job challenges and organizational knowledge and thus be able to ask questions that reflect its concerns. As in competency and derailer discussions, a face-to-face meeting is best, but if that is not practical, the discussion can be held over the phone. These discussions usually last one to two hours, depending on the number of job challenges, volume of organizational knowledge required, and whether the pool member had been asked to provide examples of experiences that relate to the targeted challenges and organizational knowledge (proof of self-evaluation).

While an HR representative usually holds these discussions, another excellent alternative is to have a member of the Executive Resource Board discuss job challenges and organizational knowledge with the pool member. A senior executive can bring a wealth of insights about the board’s standards—as well as the prestige of the position—to such a meeting. To the pool member, this involvement is yet another indication of the importance of being in the Acceleration Pool.

During these meetings the pool member should be asked about any personal or retention issues that would affect assignments or learning. Possible responses might include family constraints (e.g., a strong desire not to be moved until a child graduates high school), education plans (e.g., one year left to finish a Ph.D.), or geographic preferences (e.g., hates cold climates). The organization’s representative needs to probe for the criticality of these issues. Would an issue be so strong that ignoring it would propel the person to seek a recruiter? Such personal retention needs should be communicated to the Executive Resource Board.

We have found that clients usually have two basic questions about these discussions:

Why doesn’t the organization just accept pool members’ evaluations of job challenges and organizational knowledge? Before they meet with the HR representative or Executive Resource Board member, most Acceleration Pool members are unclear about the requirements around job challenges and organizational knowledge. Discussing these topics with someone who is well versed in them and who asks penetrating questions will crystallize understanding, generate realistic expectations, and establish evaluation standards in line with those used by the Executive Resource Board.

Why aren’t the ratings on job challenges and organizational knowledge checked with the managers in the pool member’s work area? There’s no reason that they can’t be checked, but doing so will add time and administrative work to the process. Most organizations are satisfied with the information they get from prospective pool members, so they don’t bother. Most pool members realize that they are hurting only themselves if they exaggerate the breadth and depth of their experiences. Also, because they know that senior executives will see their lists, they don’t want to be embarrassed by false claims.

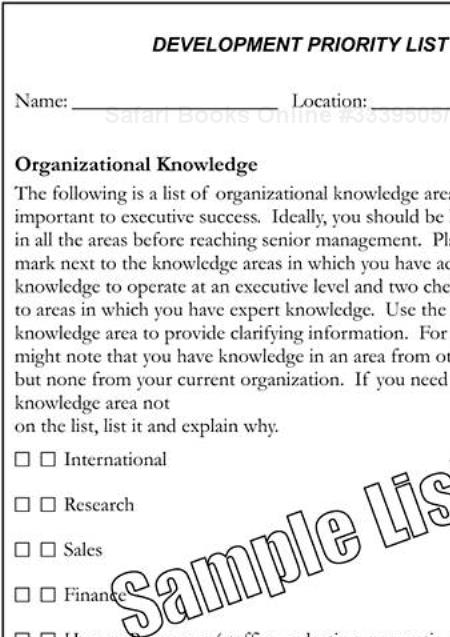

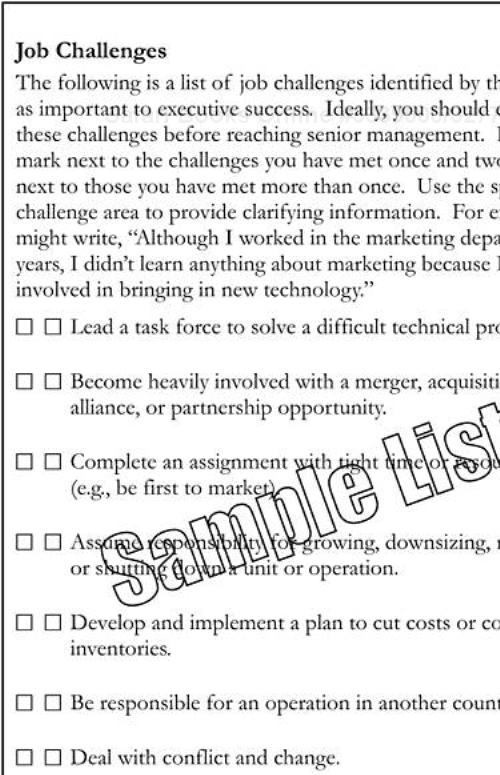

Figure 8-1 depicts an example Development Priority List completed by a first-level manager. The pool member has received Acceleration Center feedback and 360° feedback on competencies and derailers from peers and direct reports and has also discussed job challenges and organizational knowledge with a member or representative of top management. The Development Priority List shows that the pool member has chosen and prioritized the competencies, job challenges, organizational knowledge, and derailers that she needs to develop. Some descriptor categories have more areas to develop than others. The development targets in each category are listed in order of importance or need. To increase the precision of the diagnosis, the manager has noted unique information or clarification in a number of areas. This information came out of her discussion about her Acceleration Center results.

Table 8-1. Example of a Development Priority List

Name: “Noni Collins” | Date: December 2002 |

Development Priorities | |

| |

There are many variations of Development Priority Lists. For example, an organization often will provide Acceleration Pool members with a preprinted form that lists all or some of the company’s executive descriptors (see Appendix 8 on the next page). Organizations use a variety of scales to evaluate development priorities, but most methods are quite similar. The choice of a rating scale should be based on the organization’s culture and past practices.

Some Development Priority Lists include space for pool members to note progress and change ratings after they have completed an assignment or training program. This not only helps people feel good about the progress they are making, but it also provides useful information for the Executive Resource Board.

Pool members send completed Development Priority Lists to the Executive Resource Board for approval. The board’s review and approval are important for several reasons:

To show top management’s support for the Acceleration Pool system.

To make sure each pool member has a completed Development Priority List. (The pool member has a deadline for submitting the list to the board.)

To ensure that each Development Priority List reflects the findings of the Acceleration Center and any other objective input.

To make sure the priorities are in line with the organization’s business strategy (i.e., the Acceleration Pool member will be developing skills deemed most necessary to keep the organization moving in its chosen direction).

To prompt a meaningful discussion of each pool member and his or her development. Such discussions are an important part of the process of the Executive Resource Board getting to know Acceleration Pool members.

The Executive Resource Board usually accepts each pool member’s Development Priority List at face value, although there are occasions when the board will revise it. Any revisions must be explained to the pool member.