4 Possession and completion

4.1 The date of possession or commencement and the date for completion of the work are key dates in any building contract and IC16 requires a ‘Date of Possession’ and a ‘Date for Completion’ to be inserted in the contract particulars. IC16 also offers the facility for the work to be carried out in phases. If this is required, then the work must be split into clearly identified ‘Sections’, and a separate ‘Date of Possession’ and ‘Date for Completion’ entered for each section. The contractor is required to take possession on the date of possession and complete by the date for completion, and if it fails to do so it may be liable to pay liquidated damages.

4.2 There is provision for deferring the date of possession and extending the completion date. If Supplemental Provision 3 is incorporated, this could also result in an agreed adjustment to the completion date. If the work is divided into sections, provisions for commencement, completion, deferment and extension operate independently for each section.

4.3 It is good practice to give the contractor calendar dates at the time of tendering and not vague indications such as ‘to be agreed’ or ‘eight weeks after approval by’. The start date and the time of year that the work is carried out will affect the contractor’s costs, so that, unless clear dates are given, it will be impossible to compare tenders with accuracy. In addition, by the time it comes to executing the contract documents, the contractor may well protest that the dates now being proposed are not those that had been assumed in the tender, and may insist that the contract sum is adjusted.

4.4 In the event that work is started without proper agreement over dates, the contract will be subject to the Supply of Goods and Services Act 1982 or the Consumer Rights Act 2015, which state that the work should be completed within a reasonable time. If the contractor fails to complete within a reasonable time, the employer will be unable to claim liquidated damages and will have to prove any damages it wishes to recover.

4.5 Any named sub-contractor must carry out its work in accordance with the programme agreed in the sub-contract documents (ICSub/NAM/C cl 2.2). The sub-contractor is informed in the invitation to tender of the expected dates between which its work can be commenced (ICSub/NAM/IT cl 9). The sub-contractor is required to give detailed information on its requirements in respect of programming in its tender (ICSub/NAM/T cl 1). These details include the periods required for the preparation of drawings, for the incorporation of any comments, for fabrication and delivery, for notification of commencement and for carrying out the work on site. In the case of the latter, there is provision to set out separate periods where the work is to be carried out in sections.

Possession by the contractor

4.6 Possession of the site is a fundamental term of the contract. Failure to give the contractor possession is a serious breach by the employer, which may amount to repudiation and therefore give the contractor the right to treat the contract as at an end. Giving possession of only part of the site, or in stages, could amount to a breach unless this intention has been made clear in the contract documents (Whittal Builders v Chester-le-Street DC). Such breaches would constitute an ‘impediment’ under clauses 2.20.6, 4.17.4 and 8.9.2, entitling the contractor to claim an extension of time, direct loss and/or expense and, in the event of a suspension, to terminate its employment.

Whittal Builders Co. Ltd v Chester-le-Street District Council (1987) 40 BLR 82

Whittal Builders contracted with the Council on JCT63 to carry out modernisation work to 90 dwellings. The contract documents did not mention the possibility of phasing, but the Council gave the contractor possession of the houses in a piecemeal manner. Even though work of this nature was frequently phased, the judge nevertheless found that the employer was in breach of contract for not giving the contractor possession of all 90 dwellings at the start of the contract, and the contractor was entitled to damages.

4.7 Degree of possession is such that there must be no interference that prevents the contractor from working in whatever way or sequence it chooses. With most jobs this means that the contractor must be given clear possession of the whole site up until practical completion. Clause 2.4 supports this by stating that ‘the Employer shall not be entitled to take possession of any part or parts of the Works’ until the date of issue of the practical completion certificate. Where clear possession is not intended, then the tender documents should set out in detail the restrictions and the contract must be amended accordingly. Access to the site and to surrounding areas in the control of the employer should also be made clear, in case this leads to disputes (see The Queen in Rights of Canada v Walter Cabbott Construction Ltd ). Should the employer wish to use any part of the works for any purpose during the time that the contractor has possession, this should also be made clear in the tender documents, otherwise it can only be with the agreement of the contractor (cl 2.6.1). Similarly, should the employer wish the contractor to allow access for others to carry out work, this should also be made clear (cl 2.7.1).

The Queen in Rights of Canada v Walter Cabbott Construction Ltd (1975) 21 BLR 42

This Canadian case (Federal Court of Appeal) concerned work to construct a hatchery on a site (contract 1) where several other projects relating to ponds were also planned. The work to the ponds could not be undertaken without occupying part of the hatchery site. Work to the ponds was started in advance of contract 1, causing access problems to the contractor when contract 1 began. The court confirmed (at page 52) the trial judge’s view that ‘the “site for the work” must, in the case of a completely new structure comprise not only the ground actually to be occupied by the completed structure but so much area around it as is within the control of the owner and is reasonably necessary for carrying out the work efficiently’.

4.8 If clause 2.5 has been stated in the contract particulars to apply, then it is possible for the employer to defer possession of the works or any section without the agreement of the contractor (it is important to note that, if the correct deletion is not made, the clause will not apply). The clause allows for deferment for a period not exceeding six weeks; if a shorter maximum period is preferred, this must be stated in the tender documents and inserted in the contract particulars (cl 2.5). Where the work is split into sections, different maximum periods may be entered for each section. Any delay beyond the period stated is a breach of contract.

4.9 It is the employer’s right to defer possession, therefore the notice to the contractor should be written by the employer, on the advice of the contract administrator. Although the contract does not require it, it would be wise to do this as far in advance of the planned commencement date as possible. The contractor will be entitled to an extension of time (cl 2.20.3) and loss and/or expense (cl 4.15.1), and early notification should keep the losses to a minimum. The clause must be operated strictly according to the conditions, and any delay beyond the periods stated in the contract particulars would be a breach of contract.

4.10 The parties are, of course, always free to renegotiate the terms of any contract. Therefore, if there is a delay in giving possession which is longer than the amount stated in the contract particulars, or where the contract particulars have said that clause 2.5 does not apply, the parties may have to agree a new date of possession, usually with financial compensation to the contractor. Any further delay beyond the agreed date would, of course, be a breach.

Progress

4.11 It would normally be implied into a construction contract that a contractor will proceed ‘regularly and diligently’, and this is an express term in IC16 (cl 2.4). The contractor is free to organise its own working methods and sequences of operations, with the qualification that it must comply with the contract documents, statutory requirements and the construction phase plan (cl 2.1). This has been held to be the case even where the contractor’s chosen sequencing may cause extra cost to the employer with the operation of fluctuation provisions (GLC v Cleveland Bridge and Engineering).

Greater London Council v Cleveland Bridge and Engineering Co. (1986) 34 BLR 50 (CA)

The Greater London Council (GLC) employed Cleveland Bridge to fabricate and install gates and gate arms for the Thames Barrier. The specially drafted contract provided dates by which Cleveland Bridge had to complete certain parts of the works. Clause 51 was a fluctuations provision which allowed for adjustments to be made to the contract sum if, for example, the rates of wages or prices of materials rose or fell during the course of the contract. The clause also contained the phrase ‘provided that no account shall be taken of any amount by which any cost incurred by the Contractor has been increased by the default or negligence of the Contractor’. The contract was lengthy, and Cleveland Bridge left part of the work to be carried out at the very end of the period, but delivered the gates on time. The result was that the GLC had to pay a large amount of fluctuations in respect of the work done at the last minute. The GLC argued that the contractor had failed to proceed regularly and diligently, and therefore was in default. The court held that even if the slowness of the contractor’s progress might at certain points have given the employer the right to terminate the contractor’s employment under the termination provisions, this would not, in itself, be a breach of contract as referred to in clause 51. The contractor could organise the work any way it wished provided it completed on time: it was therefore owed the full amount of the fluctuations.

4.12 There is no requirement under IC16 for the contractor to produce a master programme. Of course, there is nothing to prevent such a requirement being introduced through the bill of quantities or specification, but it should be made clear that this will not be a contract document. If it is to be required, then it would be wise to stipulate that the contractor submits it before the contract is entered into. It is notoriously difficult to extract programmes from contractors once work has commenced – sometimes the programme when finally produced can include an element of post-rationalisation to show that early events caused problems and delays. If requested, it is also advisable to ask for a critical path analysis, since it can otherwise be difficult to assess the effect of delays.

4.13 One of the functions of a programme is to indicate when information will be needed from the contract administrator, and if the information release schedule is not used it would be open to the contractor to submit such a programme, even if one were not requested. Again, the programme would not be contractually binding. It should be remembered that even if the contractor’s programme shows an intention to complete early, there is no implied duty on the employer to enable the contractor to achieve this early completion (Glenlion Construction v The Guinness Trust) and, in particular, the contract administrator’s obligation to provide information would not be assessed against this programme. It would be sensible, however, to notify the employer if an early finish is shown, as the employer should be alert to the possibility that it may receive the building earlier than had been anticipated.

Glenlion Construction Ltd v The Guinness Trust (1987) 39 BLR 89

The Guinness Trust employed Glenlion Construction to carry out works in relation to a residential development at Bromley, Kent. The contract was on JCT63, which required the contractor to complete ‘on or before’ the date for completion, and to provide a programme. Disputes arose which went to arbitration and several questions of law regarding the contractor’s programme were subsequently raised in court. The contractor later claimed loss and expense on the ground that it was prevented from economic working and achieving the early completion date shown on its programme only by failure of the architect to provide necessary information and instructions by the dates shown. The court decided that Glenlion was entitled to complete before the date for completion, whether or not it was contractually bound to produce a programme and whether or not it did in fact produce one. Glenlion was therefore entitled to carry out the works in a way which would achieve an earlier completion date. However, there was no implied obligation that the employer (or the architect) should perform its obligations so as to enable the contractor to complete by any earlier completion date shown on the programme.

Completion

4.14 The most important reason for giving an exact completion date in a building contract is that it provides a fixed point from which damages may be payable in the event of non-completion. Generally, in construction contracts the damages are ‘liquidated’, and typically are fixed at a rate per week of overrun.

4.15 The contractor is obliged to complete the works by the completion date, and in general accepts the risk of all events that might prevent completion by this date. The contractor is relieved of this obligation if the employer causes delays or in some way prevents completion. In addition, most contracts contain provisions allowing for the adjustment of the completion date in the event of certain delays caused by the employer or neutral delaying events. The contract dates can, of course, always be adjusted by agreement.

4.16 In contracts it is sometimes essential that completion is achieved by a particular date and failure would mean that the result is worthless. This is sometimes referred to as ‘time is of the essence’. Breach of such a term would be considered a fundamental breach, and would give the employer the right to terminate performance of the contract and treat all its own obligations as at an end. The expression ‘time is of the essence’ is seldom, if ever, applicable to building contracts such as IC16, as the inclusion of extensions of time and liquidated damages provisions implies that the parties intended otherwise.

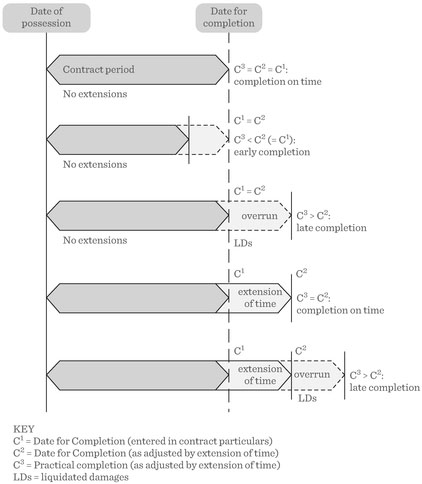

4.17 In IC16 a ‘Date for Completion’ is inserted in the contract particulars, which is the date agreed at the time of entering into the contract. If the sectional completion provisions are used, a separate date will be stated for each section. IC16 provides for the granting of extensions of time, and refers throughout the form to the ‘Completion Date’, which is the date for completion, or any extended date following an extension of time. There is no provision for reducing the contract period to a date earlier than the date for completion, even when substantial work is omitted. If the contractor fails to complete by the completion date, liquidated damages become payable (see Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1 Completion and liquidated damages

Extensions of time

Principle

4.18 The main reason for including extension of time provisions in a building contract is to preserve the employer’s right to liquidated damages in the event that the contractor fails to complete on time due, in part, to some action for which the employer is responsible. If no such provisions were included, and a delay occurred that was caused by the employer, this would in effect be a breach of contract by the employer and the contractor would no longer be bound to complete by the completion date (Peak Construction v McKinney Foundations). The employer would therefore lose the right to liquidated damages, even though much of the blame for the delay rests with the contractor. On the same principle, where the contract does provide for extensions of time to be granted, but these provisions are not operated, the employer will not be able to levy damages where it is, in part, responsible for the delay. The phrase ‘time at large’ is often used to describe this situation. However, this is, strictly speaking, a misuse of the phrase as, in most cases, the contractor would remain under an obligation to complete within a reasonable time.

Peak Construction (Liverpool) Ltd v McKinney Foundations Ltd (1970) 1 BLR 111 (CA)

Peak Construction was the main contractor on a project to construct a multi-storey block of flats for Liverpool Corporation. The main contract was not on any of the standard forms, but was drawn up by the Corporation. McKinney Foundations Ltd was the sub-contractor nominated to design and construct the piling. After the piling was complete and the sub-contractor had left the site, serious defects were discovered in one of the piles and, following further investigation, minor defects were found in several other piles. Work was halted while the best strategy for remedial work was debated between the parties. The city surveyor did not accept the initial remedial proposals, and it was agreed that an independent engineer would prepare a proposal. The Corporation refused to agree to accept his decision in advance and delayed making the appointment. Altogether it was 58 weeks before work resumed (although the remedial work took only six weeks) and the main contractor brought a claim against the sub-contractor for damages. The Official Referee at first instance found that the entire 58 weeks constituted delay caused by the nominated sub-contractor and awarded £40,000 damages for breach of contract, based in part on liquidated damages which the Corporation had claimed from the main contractor. McKinney appealed, and the Court of Appeal found that the 58-week delay could not possibly entirely be due to the sub-contractor’s breach, but was in part caused by the tardiness of the Corporation. This being the case, and as there were no provisions in the contract for extending time for delay on the part of the Corporation, it lost its right to claim liquidated damages, and this component of the damages awarded against the sub-contractor was disallowed. Even if the contract had contained such a provision, the failure of the architect to exercise it would have prevented the Corporation from claiming liquidated damages. The only remedy would have been for the Corporation to prove what damages it had suffered as a result of the breach.

Procedure

4.19 In IC16, the provisions for granting an extension of time are under clauses 2.19 and 2.20. The contractor must give written notice ‘forthwith’ to the contract administrator when it appears that progress is being or is likely to be delayed. The notice must be given whether or not completion is likely to be delayed, whatever the cause might be (i.e. the requirement to give a notice is not limited to circumstances where the contractor is claiming an extension of time). The notice should set out the cause of the delay, but the contractor is not required to identify whether the cause is a ‘Relevant Event’ listed in clause 2.20, and the contract administrator’s obligation to issue an appropriate extension of time is not dependent on the contractor having done so. However, the contractor is required to provide the contract administrator with any information reasonably required (cl 2.19.4.2), and to issue a further notice if there is any further delay (cl 2.19.5).

4.20 Although the point has not been decided by the courts in relation to IC16, it appears that, prior to the completion date, notification is likely to be a condition precedent to the award of an extension of time; in other words, the contract administrator may not issue an extension unless a valid notice has been given. In any event, it would be difficult to make an assessment in the absence of any information from the contractor, and clause 2.19.4.2 makes it clear that the award of an extension of time is dependent on the provision of reasonably necessary information (a relevant case is Steria Ltd v Sigma Wireless Communications Ltd).

Steria Ltd v Sigma Wireless Communications Ltd (2007) 118 Con LR 177

This case concerned a sub-contract to provide a computer-aided dispatch system, where the contractor, Sigma, refused to make the final payment due to the sub-contractor, Steria, at the end of the defects period. Sigma argued that Steria had delayed the completion of the sub-contract works and so it was entitled to withhold liquidated damages. In response, Steria argued that it was entitled to an extension of time. A dispute arose as to whether the notice provisions in the contract created a condition precedent. The relevant clause stated ‘provided the Sub-Contractor shall have given within a reasonable period written notice to the Contractor of the circumstances giving rise to the delay, the time for completion hereunder shall be extended by such period as may in all the circumstances be justified …’. The court found that the use of the word ‘provided’ imposed a clear and unqualified condition that Steria would only be entitled to an extension if it gave a compliant notice. A notification requirement can operate as a condition precedent even though it does not contain any express warning as to the consequences of non-compliance.

4.21 Following notification, the contract administrator must then assess the delay caused and issue an extension of time, if appropriate. The extension can only be given in relation to delay caused by events listed in clause 2.20.

4.22 In regard to relevant events, the following points should be noted:

- the contractor will be entitled to an extension following any exercise of its right of suspension arising from non-payment of amounts due by the employer (cl 2.20.5);

- the phrase ‘any impediment, prevention or default’ (cl 2.20.6) covers a very wide range of possible acts by the employer, contract administrator, quantity surveyor or any ‘Employer’s Person’, and would include, for example, failure to provide a drawing at the time shown on the information release schedule;

- clause 2.20.7 applies only to statutory undertakers operating independently. Work carried out by a statutory undertaker under a contract with the employer would fall under clause 2.20.6 and, if under a contract with the contractor, any delays would be at the contractor’s risk;

- weather has to be exceptional and adverse (i.e. not that which would be expected at the time of year in question, cl 2.20.8). The effect of the weather is assessed at the time the work is actually carried out, not when it should have been, according to the contractor’s programme. The contractor will normally provide weather records to support its claim;

- specified perils (cl 2.20.9) can, under certain circumstances, include events caused by the contractor’s own negligence;

- civil commotion and terrorism under clause 2.20.10 includes the threat of terrorism and activities of relevant authorities in dealing with such threats;

- a very wide protection is afforded with respect to strikes (cl 2.20.11), and not simply those directly affecting the works, but also those causing difficulties in preparation and transportation of goods and materials. Such strikes will not necessarily be confined to the UK and, given the current extent of overseas supply chains, the effects could be considerable. It was generally considered, however, that the fuel tax blockades in 2000 were not an event which fell under this clause (or indeed constituted any other relevant event);

- ‘force majeure’ (cl 2.20.13) is a French term used ‘with reference to all circumstances independent of the will of man, and which it is not in his power to control’. It includes Acts of God and other matters outside the control of the parties. However, many items under this category, e.g. strikes, fire and weather, are dealt with elsewhere in the contract.

4.23 There is no time limit on when the decision regarding an extension of time should be made (cl 2.19.1). However, the clause states ‘as soon as he is able’ and, as failure to grant an extension properly due could result in time being ‘at large’, the contract administrator should take care to deal with the matter reasonably quickly. It certainly would be unwise to set the matter to one side until the end of the project. The clause does not require the contract administrator to notify the contractor if the decision is that no extension of time is due, but it would be reasonable to make the contractor aware of the position. There is also no obligation to explain why any extension has been awarded.

4.24 The contract administrator may award further extensions of time in respect of certain events which occur after the date for completion or any extended date, i.e. when the contractor is in ‘culpable delay’ (Balfour Beatty v Chestermont Properties), and must award one if due, irrespective of whether any notice has been issued by the contractor (cl 2.19.2). In this event the extension is added onto the date that has passed, referred to as the ‘net’ method of extension. The range of events is less than those for which an extension can be awarded before the completion date has passed: it does not include many neutral events, such as delays by the specified perils or the contractor’s inability, for reasons beyond its control, to secure necessary labour.

Balfour Beatty Building Ltd v Chestermont Properties Ltd (1993) 62 BLR 1

In a contract on JCT80, the works were not completed by the revised completion date and the architect issued a non-completion certificate. The architect then issued a series of variation instructions and a further extension of time, which had the effect of fixing a completion date two-and-a-half months before the first of the variation instructions. He then issued a further non-completion certificate and the employer proceeded to deduct liquidated damages. The contractor took the matter to arbitration and then appealed certain decisions on preliminary questions given by the arbitrator. The court held that the architect’s power to grant an extension of time pursuant to clause 25.3.1.1 could only operate in respect of relevant events that occurred before the original or the previously fixed completion date, but the power to grant an extension under clause 25.3.3 applied to any relevant event. The architect was right to add the extension of time retrospectively (termed the ‘net’ method).

4.25 The contract administrator may make a further extension of time at any time up to 12 weeks after practical completion (cl 2.19.3), and may review any extension of time previously given. The final review may extend the date previously fixed but may not bring it forward, although the contract administrator may be able to offset a reduction or omission of work against the effect of another delaying event. It is clear that, at this point, there is no requirement for notification by the contractor. There is no requirement to notify the contractor if it is decided that no further extension is due, but again it would be reasonable to do so.

Assessment

4.26 The contractor is entitled to extensions of time properly due under the contract and any failure on the part of the contract administrator to administer the provisions correctly would constitute a breach of contract on the part of the employer. On the other hand, the contract administrator has no power to grant extensions of time except as provided for in the contract, and for delays caused by relevant events as listed in clause 2.20.

4.27 The contract administrator should make an objective assessment of every notice received. The aim is to establish, if a delay has been caused by the event cited, whether the delay is likely to disrupt the programme and consequently delay the final completion date and, if so, to assess the probable extent of that final delay. The contractor’s programme can be used as a guide and may be particularly useful where the programme shows a critical path but, although it may be persuasive evidence, it is not conclusive or binding. The effect on progress is assessed in relation to the work being carried out at the time of the delaying event, rather than the work that was programmed to be carried out.

4.28 Clause 2.19 contains the important proviso that the contractor must ‘constantly use his best endeavours to prevent delay’ (cl 2.19.4.1). The proviso refers to preventing delay caused by a relevant event, not to preventing the event itself. The contract administrator can assume, therefore, that the contractor will take steps to minimise the effect of the delay on the completion date, e.g. through reprogramming the remaining works. The phrase ‘best endeavours’ appears to suggest something more than ‘reasonable’ or ‘practicable’ but it is unlikely to extend to excessive expenditure. Clause 2.19.4.1 also states that the contractor shall ‘do all that may reasonably be required to the satisfaction of the Architect/Contract Administrator to proceed with the Works’. However, if the contract administrator requires measures which amount to a variation, then this may result in a claim for loss and/or expense. It should also be noted that the contractor is not to be given an extension of time where delays are caused by the defaults set out in clause 2.14.1 and 2.14.2 (ICD16 only), i.e. errors in the contractor’s proposals or delays in submitting contractor’s design documents.

4.29 The effects of any delay on completion – taking into account the contractor’s ‘best endeavours’ – are not always easy to predict. The contract administrator is required to reach an opinion, and in doing this the contract administrator owes a duty to both parties to be fair and reasonable (Sutcliffe v Thackrah, see paragraph 7.3). This applies even where the delay has been caused by the contract administrator, for example where the contract administrator has failed to issue drawings within the time limits stipulated in the contract.

4.30 It sometimes happens that two or more delaying events can occur simultaneously, or with some overlap, and this can raise difficult questions with respect to the awarding of extensions of time. In the case of concurrent delays involving two or more relevant events (cl 2.20), it has been customary to grant the extension in respect of the dominant event, but this is only appropriate where the dominant event begins before, and ends after, any other event. Even then, if the dominant event is not a ground for loss and expense, this may still be due in respect of the other delaying events (H Fairweather & Co. v Wandsworth).

H Fairweather & Co. Ltd v London Borough of Wandsworth (1987) 39 BLR 106

Fairweather entered into a contract with the London Borough of Wandsworth to erect 478 dwellings. The contract was on JCT63. Pipe Conduits Ltd was the nominated sub-contractor for underground heating works. Disputes arose and an arbitrator was appointed who made an interim award. Leave to appeal was given on several questions of law arising out of the award. The arbitrator had found that, where a delay occurred which could be ascribed to more than one event, the extension should be granted for the dominant reason. Strikes were the dominant reason, and the arbitrator had therefore granted an extension of 81 weeks, and made it clear that this reason did not carry any right to claim for direct loss and/or expense. The court stated that an extension of time was not a condition precedent to an award of direct loss and/or expense, and that the contractor would be entitled to claim for direct loss and/or expense for other events which had contributed to the delay.

4.31 Where one overlapping delaying event is a clause 2.20 event and the other is not, in other words one is the employer’s risk and the other the contractor’s, a difficult question arises as to what extension of time is due. The instinctive reaction of many assessors might be to ‘split the difference’, given that both parties have contributed to the delay. However, the more logical approach is that the contractor should be given an extension of time for the full length of delay caused by the relevant event, irrespective of the fact that, during the overlap, the contractor was also causing delay. Taking any other approach, for example splitting the overlap period and awarding only half of the extension to the contractor, could result in the contractor being subject to liquidated damages for a delay partly caused by the employer. The courts have normally adopted this analysis (Henry Boot Construction (UK) Limited v Malmaison Hotel). More recently, in the much publicised Scottish case of City Inn Ltd v Shepherd Construction Ltd, the courts stated that a proportional approach would be fairer. This decision, however, is not binding on English courts and has not been followed (see Walter Lilly & Co. Ltd v Giles Mackay & DMW Ltd); therefore the Malmaison approach remains the correct one to adopt.

Henry Boot Construction (UK) Ltd v Malmaison Hotel (Manchester) Ltd (1999) 70 Con LR 32 (TCC)

The employer, Malmaison, engaged Henry Boot to construct a new hotel in Piccadilly, Manchester. Completion was fixed for 21 November 1997, but was not achieved until 13 March 1998. However, extensions of time were issued by the architect revising the date for completion to 6 January 1998. Malmaison deducted liquidated damages from the contract sum. Although Henry Boot claimed further extensions of time in respect of a number of alleged relevant events, no further extensions of time were awarded. The case went to arbitration and the decision was challenged through court proceedings. Among other matters, the judge considered concurrency. If it can be shown that there are two equal and concurrent causes of delay, for which the employer and contractor are respectively responsible, then the contractor is still entitled to an extension of time. Judge Dyson illustrated his views on concurrency by citing the example of the start of a project being held up for one week by exceptionally inclement weather (a relevant event), while at the same time the contractor suffered a shortage of labour (not a relevant event). In effect, the two delays and causes were concurrent. In this situation, Judge Dyson said that the contractor should be awarded an extension of time of one week, and an architect should not deny the contractor an extension on the grounds that the project would have been delayed by the labour shortage.

City Inn Ltd v Shepherd Construction Ltd [2008] CILL 2537, Outer House Court of Session

In considering a case involving a dispute over extensions of time under a JCT80 form of contract, the court considered earlier authorities and the principles underlying extension of time clauses and set out several propositions. These included that, where there are several causes of delay and where a dominant cause can be identified, the assessor can use the dominant cause and set aside immaterial causes. However, where there are two causes of delay, only one of which is a contractor default, the assessor may apportion delay between the two events. The CILL editors describe this as going ‘further than any recent authority’ on concurrency. Assessors should note that this is a Scottish case which has not, to date, been followed in English courts.

Walter Lilly & Co. Ltd v Giles Mackay & DMW Ltd [2012] EWHC 649 (TCC)

This case concerned a contract to build Mr and Mrs Mackay’s, and two other families’, luxury new homes in South Kensington, London. The contract was entered into in 2004 on the JCT Standard Form of Building Contract 1998 Edition with a Contractor’s Designed Portion Supplement. The total contract sum was £15.3 million, the date for completion was 23 January 2006 and liquidated damages were set at £6,400 per day. Practical completion was certified in August 2008. The contractor (Walter Lilly) issued 234 notices of delay and requests for extensions of time, of which fewer than a quarter were answered. The contractor brought a claim for, among other things, an additional extension of time. The court awarded a full extension up to the date of practical completion. It took the opportunity to review approaches to dealing with concurrent delay, including that in the case of Henry Boot Construction (UK) Ltd v Malmaison Hotel (Manchester) Ltd (which established that the contractor is entitled to a full extension of time for delay caused by two or more events, provided one is an event which entitles it to an extension under the contract), and the alternative approach in the Scottish case of City Inn Ltd v Shepherd Construction Ltd (where the delay is apportioned between the events). The court decided that the former was the correct approach in this case. As part of its reasoning, the court noted that there was nothing in the relevant clauses to suggest that the extension of time should be reduced if the contractor was partly to blame for the delay.

Partial possession

4.32 The employer may take possession of completed parts of the works ahead of practical completion by operating clause 2.25. ‘Partial possession’ requires the agreement of the contractor, which cannot be unreasonably withheld. To bring the provision into operation the contract administrator must issue a written statement to the contractor identifying precisely the extent of the ‘Relevant Part’ and the date of possession (the ‘Relevant Date’). This should be done with great care, even using a drawing to illustrate the extent, and communicating with the insurers where relevant. The statement must be issued immediately after the part is taken into possession, but in practice it would be wise to circulate the drawings and information in advance, so that all parties are clear as to the details of what will occur. The partial possession may affect other operations on site, in which case it could constitute an ‘impediment’, therefore the employer should be warned of the possible contractual consequences in terms of delay and claims for loss and/or expense.

4.33 Practical completion is ‘deemed to have occurred’ for the ‘Relevant Part’ of the works and the rectification period for that part is deemed to have commenced on the relevant date. The certificate of making good has to be issued for that part separately (cl 2.27). However, it would appear that this remains part of the works, and is still to be included under the certificate of practical completion. It is notable that the clause does not state that the works to that part must have reached practical completion, but in view of the contractual consequences it would be unwise for the employer to take possession before they have (see paragraph 4.43).

4.34 Liquidated damages are reduced by the proportion of the value of the ‘Relevant Part’ of the works to the contract sum (cl 2.29). The effect of clause 4.9.1 is that half of the retention is released for that proportion of the works. If Insurance Option A, B or C2 applies, the employer may wish to consider insuring the part as the contractor’s obligation to insure the works will cease (cl 2.28).

4.35 It is important to note that the fact that significant work remains outstanding has not prevented the courts from finding that ‘partial possession’ has been taken of the whole works in situations where a tenant has effectively occupied the whole building, allowing access to the contractor for remedial work (see Skanska Construction (Regions) Ltd v Anglo-Amsterdam Corporation Ltd). If the parties do not intend clause 2.25 to take effect for the whole project, they must make clear, under a carefully worded agreement, what are the contractual consequences of any intended occupation (see below).

Skanska Construction (Regions) Ltd v Anglo-Amsterdam Corporation Ltd (2002) 84 Con LR 100

Anglo-Amsterdam Corporation (AA) engaged Skanksa Construction (Skanska) to construct a purpose-built office facility under a JCT81 With Contractor’s Design form of contract. Clause 16 had been amended to state that practical completion would not be certified unless the certifier was satisfied that any unfinished works were ‘very minimal and of a minor nature and not fundamental to the beneficial occupation of the building’. Clause 17 of the form stated that practical completion would be deemed to have occurred on the date that the employer took possession of ‘any part or parts of the Works’.

AA wrote to Skanska confirming that the proposed tenant for the building would commence fitting-out works on the completion date. However, the air-conditioning system was not functioning and Skanska had failed to produce operating and maintenance manuals. Following this date the tenant took over responsibility for security and insurance and Skanska was allowed access to complete outstanding work. AA alleged that Skanska was late in the completion of the works and applied liquidated damages at the rate of £20,000 per week for a period of approximately nine weeks. Skanska argued that the building had achieved practical completion on time or that, alternatively, partial possession of the works had taken place and that, consequently, its liability to pay liquidated damages had ceased under clause 17.

The case went to arbitration and Skanska appealed. The court was unhappy with the decision and found that clause 17.1 could also operate when possession had been taken of all parts of the works and was not limited to possession of only part or some parts of the works. Accordingly, it found that partial possession of the entirety of the works had, in fact, been taken some two months earlier than the date of practical completion, when AA agreed to the tenant commencing fit-out works. Consequently, even though significant works remained outstanding, Skanska was entitled to repayment of the liquidated damages that had already been deducted by AA.

Use or occupation before practical completion

4.36 Clause 2.6 provides for the situation where the employer wishes to ‘use or occupy the site or the Works or part of them’ while the contractor is still in possession. The written consent of the contractor is required. The purposes for which the employer might require such use are described simply as ‘storage or otherwise’ and, while this might suggest that the intention is of a limited nature, in theory at least the clause places no limits on what form such use or occupation might take. In practice, occupation could in some circumstances cause an ‘impediment’ to the progress of the works, and therefore constitute a relevant event under clause 2.20.6 and a relevant matter under clause 4.17.4. It would be sensible to agree the contractual consequences before the occupation takes place, unless it can be established that the use or occupation is unlikely to cause delays. Before the contractor is required to give consent, the employer or the contractor (as appropriate) must notify the insurers. Any additional premium required is added to the contract sum (cl 2.6.2).

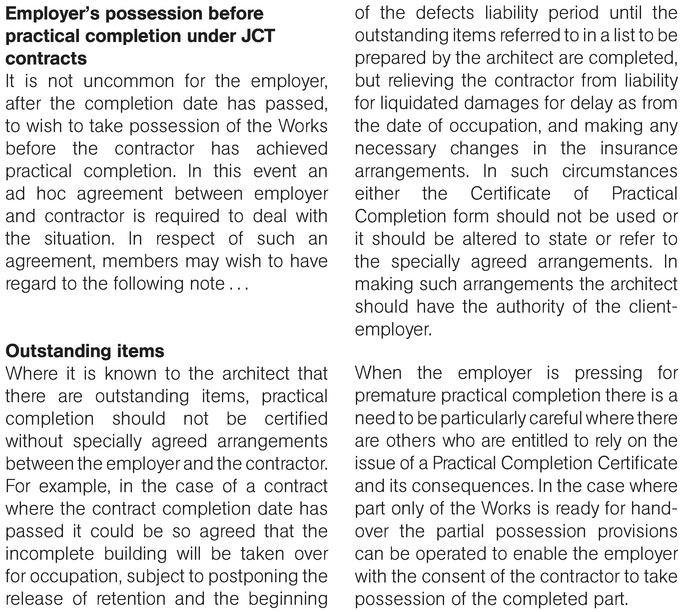

4.37 Situations can arise where the contractor has not completed by the date for completion and, although no sections of the works are sufficiently complete to allow the employer to take possession of those parts under clause 2.25, the employer is nevertheless anxious to occupy at least part of the works. There is nothing in the contract that allows for this. A suggestion was put forward in the ‘Practice Section’ of the RIBA Journal (February 1992) which has frequently proved useful in practice (see Figure 4.2): in return for being allowed to occupy the premises, the employer agrees not to claim liquidated damages during the period of occupation. Practical completion obviously cannot be certified, and there is no release of retention money until it is. Matters of insuring the works will need to be settled with the insurers.

4.38 Because such an arrangement would be outside the terms of the contract, it should be covered by a properly drafted agreement which is signed by both parties. (The cases of Skanska v Anglo-Amsterdam Corporation above and Impresa Castelli v Cola illustrate the importance of drafting a clear agreement.) It may also be sensible to agree that, in the event that the contractor still fails to achieve practical completion by the end of an agreed period, liquidated damages would begin to run again, possibly at a reduced rate. In most circumstances this arrangement would be of benefit to both parties, and is certainly preferable to issuing a heavily qualified practical completion certificate listing ‘except for’ items.

Figure 4.2 ‘Practice’ section, RIBA Journal (February 1992)

Impresa Castelli SpA v Cola Holdings Ltd (2002) CLJ 45

Impresa agreed to build a large four-star hotel for Cola Holdings Ltd (Cola), using the JCT Standard Form of Building Contract With Contractor’s Design, 1981 edition. The contract provided that the works would be completed within 19 months from the date of possession. As the work progressed, it became clear that the completion date of February 1999 was not going to be met, and the parties agreed a new date for completion in May 1999 (with the bedrooms being made available to Cola in March) and a new liquidated damages provision of £10,000 per day, as opposed to the original rate of £5,000. Once the agreement was in place, further difficulties with progress were encountered, which meant that the May 1999 completion date was also unachievable. The parties entered into a second variation agreement, which recorded that access for Cola would be allowed to parts of the hotel to enable it to be fully operational by September 1999, despite certain works not being complete (including the air conditioning). In September 1999, parts of the hotel were handed over, but Cola claimed that such parts were not properly completed. A third variation agreement was put in place with a new date for practical completion and for the imposition of liquidated damages.

Disputes arose and, among other matters, Cola claimed for an entitlement to liquidated damages. Impresa argued that it had achieved partial possession of the greater part of the works, therefore a reduced rate of liquidated damages per day was due. The court found that, although each variation agreement could have used the words ‘partial possession’, they had in fact instead used the word ‘access’. The court had to consider whether partial possession had occurred under clause 17.1 of the contract, which provides for deemed practical completion when partial possession is taken, or whether Cola’s presence was merely ‘use or occupation’ under clause 23.3.2 of the contract. The court could find nothing in the variation agreements to suggest that partial possession had occurred. It therefore ruled that what had occurred related to use and occupation, as referred to in clause 23.3.2 of the contract, and that the agreed liquidated damages provision was therefore enforceable.

Practical completion

4.39 The contract administrator is obliged to certify practical completion of the works or of a section (cl 2.21.1) when, in the contract administrator’s opinion, the following two criteria are fulfilled:

- practical completion of the works is achieved (see below);

- the contractor has sufficiently complied with clause 3.18 (supply of information required for the health and safety file).

In addition, in the case of ICD16 only, the contractor must have sufficiently complied with clause 2.32 (supply of as-built drawings).

4.40 Clause 2.21 then continues by stating that ‘practical completion of the Works or the Section shall be deemed for all the purposes of this Contract to have taken place on the date stated in that certificate’. Although the wording of clause 2.21 is somewhat circular, effectively saying that ‘practical completion of the Works or the Section’ is to be certified when ‘practical completion of the Works or the Section’ plus another event has taken place, it is suggested that a correct analysis of this clause is that practical completion only occurs when both conditions are met, the principal argument for this reasoning being that only one date is entered on the certificate. This should be the date when the last condition is fulfilled; in other words, if there is a delay before receiving the as-built drawings, the date of their receipt should be the date on the certificate, irrespective of the fact that the works were complete days or even weeks earlier.

4.41 It should be noted that the use of the term ‘complied sufficiently’ may allow the contract administrator to use discretion in issuing the certificate with some very minor information missing. The contract administrator should, however, be very careful not to place the employer in a position where it would be in breach of the Construction (Design and Management) Regulations 2015.

4.42 Deciding when the works have reached practical completion often causes some difficulty. It is suggested that practical completion means the completion of all works required under the contract and by subsequent instruction. Although it has been held that the contract administrator has discretion to certify practical completion where there are very minor items of work left incomplete, on de minimis principles (H W Nevill (Sunblest) v William Press), this discretion should be exercised with extreme caution. Contrary to the opinion of many contractors, there is no obligation to issue the certificate when the project is ‘substantially’ complete, or even when it is capable of occupation by the client, if there are items still outstanding.

H W Nevill (Sunblest) Ltd v William Press & Son Ltd (1981) 20 BLR 78

William Press entered into a contract with Sunblest to carry out foundations, groundworks and drainage for a new bakery on a JCT63 contract. A practical completion certificate was issued and new contractors commenced a separate contract to construct the bakery. A certificate of making good defects and a final certificate were then issued for the first contract, following which it was discovered that the drains and the hardstanding were defective. William Press returned to site and remedied the defects, but the second contract was delayed by four weeks and Sunblest suffered damages as a result. It commenced proceedings, claiming that William Press was in breach of contract and, in its defence, William Press argued that the plaintiff was precluded from bringing the claim by the conclusive effect of the final certificate. Judge Newey decided that the final certificate did not act as a bar to claims for consequential loss. In reaching this decision, he considered the meaning and effect of the certificate of practical completion and stated ‘I think that the word “practically” in clause 15(1) gave the architect a discretion to certify that William Press had fulfilled its obligation under clause 21(1) where very minor de minimis work had not been carried out, but that if there were any patent defects in what William Press had done then the architect could not have issued a Certificate of Practical Completion’ (at page 87).

4.43 The reason for proceeding with extreme caution is the considerable complications that can arise as a result of premature certification. Even though the employer, anxious to move into the newly completed works, may be pressing for early completion, and the contractor, anxious to avoid liquidated damages, may be even more enthusiastic, the temptation to issue the certificate, particularly one qualified by long schedules of outstanding work, should be resisted. The contract administrator should explain to the employer that they would be in a difficult position contractually, as the following contractual problems will remain unresolved:

- half of the retention will be released, leaving only half in hand (cl 4.9.1). This puts the employer at considerable risk, as the 2.5 per cent remaining from the 5 per cent stated in the contract particulars is only intended to cover latent defects;

- the rectification period begins (cl 2.30);

- the onus shifts to the contract administrator to notify the contractor of all necessary outstanding work under clause 2.30. If the contract administrator fails to include any item, the contractor would have no authority to enter the site to complete it – therefore the contract administrator will inevitably become involved in managing and programming the outstanding work;

- possession of the site now passes to the employer, and the contractor will no longer cover the insurance of the works;

- the contractor’s liability for liquidated damages ends;

- the employer will be the ‘occupier’ for the purposes of the Occupiers’ Liability Acts 1957 and 1984 and may also be subject to health and safety claims.

4.44 The certificate must be issued as soon as the criteria in clause 2.21 are met. The contractor is obliged to complete ‘on or before’ the completion date and once practical completion is certified the employer is obliged to accept the works. Employers who wish to accept the works only on the date given in the contract will need to amend the wording. If sectional completion is used, practical completion must be certified for each section of the works.

Procedure at practical completion

4.45 The contract sets out no procedural requirements for what must happen at practical completion, it simply requires the contract administrator to certify it. The contract bills may set out a procedure, and the contract administrator should check carefully at tender stage to ensure that the procedure is satisfactory.

4.46 Leading up to practical completion, it appears to be widespread practice for contract administrators to issue ‘snagging’ lists, sometimes highly detailed and on a room-by-room basis. The contract does not require this, and neither do most standard terms of appointment. Under the contract, responsibility for quality control and snagging rests entirely with the contractor. In adopting this role, the contract administrator may be assisting the contractor and, although this may appear to benefit the employer, it may lead to confusion over the liability position, which could cause problems at a future date. If the contract administrator feels that the works are not complete, there is no obligation to justify this opinion with detailed schedules of outstanding items. It is suggested that the best course may be to draw attention to typical items, but to make it clear that the list is indicative and not comprehensive.

4.47 It is common practice for the contractor to arrange a ‘handover’ meeting. The term is not used in IC16 and, although handover meetings can be useful, particularly in introducing the finished project to the employer, the fact that one has been arranged or taken place is of no contractual significance. Even where a meeting has taken place at which the employer has expressed approval of the works, or the contractor has stated in writing that the works are complete, it remains the contract administrator’s responsibility to decide when practical completion has been achieved.

Failure to complete by the completion date

4.48 In the event of failure to complete by the completion date, the contract administrator is required to certify this fact as a certificate of non-completion (cl 2.22). It should be noted that the issue of the certificate is an obligation on the contract administrator and not a matter of discretion. It should be issued promptly, as the certificate is a condition precedent to deduction of liquidated damages (cl 2.23). If the works are divided into sections, a separate certificate will be needed for each incomplete section. Once the certificate has been issued, the contractor is said to be in ‘culpable delay’. The employer, provided that it has issued the necessary notices, may then deduct the damages from the next interim certificate, or reclaim the sum as a debt. Note that fluctuations provisions are frozen from this point. If a new completion date is later set, this has the effect of cancelling the certificate of non-completion and the contract administrator must issue a further certificate of non-completion if necessary.

Liquidated damages

4.49 The agreed rate for liquidated damages for each section or for the works is entered in the contract particulars. This is normally expressed as a specific sum per week (or other unit) of delay, to be allowed by the contractor in the event of failure to complete by the completion date (note there may be several different rates where the works are divided into sections). As a result of two decisions in the Supreme Court, it is no longer considered essential that the amount is calculated on the basis of a genuine pre-estimate of the loss likely to be suffered (Cavendish Square Holdings v El Makdessi and ParkingEye Limited v Beavis; see also Alfred McAlpine Capital Projects v Tilebox). Provided that the amount is not ‘out of all proportion’ to the likely losses, the damages will be recoverable without the need to prove the actual loss suffered, irrespective of whether the actual loss is significantly less or more than the recoverable sum (BFI Group of Companies v DCB Integration Systems). In other words, once the rate has been agreed, both parties are bound by it. Of course, for practical reasons, the rate should always be discussed with the employer before inclusion in the tender documents, and an amount that will provide adequate compensation included to cover, among other things, any additional professional fees that may be charged during this period. If ‘nil’ is inserted then this may preclude the employer from claiming any damages at all (Temloc v Errill), whereas if the contract particulars are left blank the employer may be able to claim general damages.

Cavendish Square Holdings v El Makdessi and ParkingEye Limited v Beavis, Supreme Court 2015

In this landmark case the Supreme Court restated the law regarding whether a liquidated damages clause may be considered a penalty. Key criteria for whether a provision will be penal are if the sum stipulated is ‘exorbitant or unconscionable’ in comparison with ‘the greatest loss that could conceivably be proved to have followed from the breach’; and whether the sum imposes a detriment on the contract breaker which is ‘out of all proportion to any legitimate interest of the innocent party’. In determining these, the court must consider the wider commercial context.

Alfred McAlpine Capital Projects Ltd v Tilebox Ltd [2005] BLR 271

This case contains a useful summary of the law relating to the distinction between liquidated damages and penalties. A WCD98 contract contained a liquidated damages provision in the sum of £45,000 per week. On the facts, this was a genuine pre-estimate of loss and the actual loss suffered by the developer, Tilebox, was higher. The contractor therefore failed to obtain a declaration that the provision was a penalty. The judge also considered a different (hypothetical) interpretation of the facts whereby it was most unlikely, although just conceivable, that the total weekly loss would be as high as £45,000. In this situation also the judge considered that the provision would not constitute a penalty. In reaching this decision he took into account the fact that the amount of loss was difficult to predict, that the figure was a genuine attempt to estimate losses, that the figure was discussed at the time that the contract was formed and that the parties were, at that time, represented by lawyers.

BFI Group of Companies Ltd v DCB Integration Systems Ltd [1987] CILL 348

BFI employed DCB on the Agreement for Minor Building Works to refurbish and alter offices and workshops at its transport depot. BFI was given possession of the building on the extended date for completion, but two of the six vehicle bays could not be used for a further six weeks as the roller shutters had not yet been installed. Disputes arose which were taken to arbitration. The arbitrator found that the delay in completing the two bays did not cause BFI any loss of revenue, and that BFI was therefore not entitled to any of the liquidated damages. BFI was given leave to appeal to the High Court. HH Judge John Davies QC found that BFI was entitled to liquidated damages. It was quite irrelevant to consider whether in fact there was any loss. Liquidated damages do not run until possession is given to the employer but until practical completion is achieved, which may not be at the same time. Therefore, the fact that the employer had use of the building was also not relevant.

Temloc Ltd v Errill Properties Ltd (1987) 39 BLR 30 (CA)

Temloc entered into a contract with Errill Properties to construct a development near Plymouth. The contract was on JCT80 and was in the value of £840,000. ‘£ nil’ was entered in the contract particulars against clause 24.2, liquidated and ascertained damages. Practical completion was certified around six weeks later than the revised date for completion. Temloc brought a claim against Errill Properties for non-payment of some certified amounts, and Errill counterclaimed for damages for late completion. It was held by the court that the effect of ‘£ nil’ was not that the clause should be disregarded (because, for example, it indicated that it had not been possible to assess a rate in advance), but that it had been agreed that no damages would be payable in the event of late completion. Clause 24 is an exhaustive remedy and covers all losses normally attributable to a failure to complete on time. The defendant could not, therefore, fall back on the common law remedy of general damages for breach of contract.

4.50 Before liquidated damages may be claimed, the following preconditions must have been met:

- the contractor must have failed to complete the works by the date for completion or any extended date;

- the contract administrator must have issued a certificate of non-completion (cl 2.22);

- the contract administrator must have fulfilled all duties with respect to the award of an extension of time (cl 2.19.2);

- the employer must have given the contractor written notice of its intention before the date of the final certificate (cl 2.23.1.2).

4.51 The clause 2.23.1.2 notice must be reasonably clear, but there is no need for a great deal of detail (Finnegan v Community Housing Association). Provided these conditions have been met, the employer may, by means of a further notice ‘not later than 5 days before the final date for payment of the amount payable under clause 4.21’, recover the liquidated damages (cl 2.23.1). The notice to be given depends on whether the employer intends to deduct liquidated damages from monies due, or to require the contractor to pay the sum to the employer (cl 2.23.2). If the employer wishes to recover the amount as a debt then this has to be notified as set out in clause 2.23.2.1. If the employer wishes to deduct liquidated damages from an amount payable on a certificate, then a clause 2.23.2.2 notice is needed. In addition to this notice, footnote [38] (or [40] in ICD16) to clause 2.23.2.2 states that the employer must give the appropriate ‘Pay Less Notice’ under clause 4.12.5. Although the pay less notice may seem to be something of a duplication of the clause 2.32.2.2 notice, in that if correctly worded one document could cover both clauses, it would be wise to follow the footnote exactly and issue two separate notices complying precisely with the respective clauses.

J F Finnegan Ltd v Community Housing Association Ltd (1995) 77 BLR 22 (CA)

Finnegan Ltd was employed by the Housing Association to build 18 flats at Coram Street, West London. The contractor failed to complete the work on time, and the contract administrator issued a certificate of non-completion. Following the certificate of practical completion, an interim certificate was issued. The employer sent a notice with the cheque honouring the certificate, which gave minimal information (i.e. not indicating how liquidated and ascertained damages (LADs) had been calculated). The Court of Appeal considered this sufficient to satisfy the requirement for the employer’s written notice in clause 24.2.1. Peter Gibson LJ stated (at page 33):

He then stated (at page 35):

The requirements relating to notices have now changed. However, there appears to be no reason why the general comments would not still apply, i.e. that the amount of information required would be no more than the minimum set out in the contractual provisions.

4.52 If an extension of time is given following the issue of a certificate of non-completion, then this has the effect of cancelling that certificate. A new certificate of non-completion must be issued if the contractor then fails to complete by the new completion date (cl 2.22). The employer must, if necessary, repay any liquidated damages recovered for the period up to the new completion date (cl 2.24), and must do so within a reasonable period of time (Reinwood v L Brown & Sons). Clause 2.23.3 also states that any notice issued by the employer under clause 2.23.1.2 shall remain effective, unless the employer states otherwise in writing, notwithstanding that a further extension of time has been granted. Nevertheless, it is suggested that, if the intention is to withhold payments due and the deduction was postponed to a later certificate, fresh notices should be issued.

Reinwood Ltd v L Brown & Sons Ltd [2007] BLR 305 (CA)

This dispute concerned a contract on JCT98, with a date for completion of 18 October 2004, and LADs at the rate of £13,000 per week. The project was delayed, and on 7 December 2005, the contractor made an application for an extension of time. On 14 December 2005, the contract administrator issued a certificate of non-completion under clause 24.1. On 11 January 2006, the contract administrator issued interim certificate no. 29 showing the net amount for payment as £187,988. The final date for payment was 25 January 2006.

On 17 January 2006, the employer issued notices under clause 24.2 and 30.1.1.3 of its intention to withhold £61,629 of LADs, and the employer duly paid £126,359 on 20 January 2006.

On 23 January 2006, the contract administrator granted an extension of time until 10 January 2006, following which the contractor wrote to the employer stating that the effect of the extension of time and revision of the completion date was that the employer was now entitled to withhold no more than £12,326. The amount due under interim certificate no. 29 was, therefore, £175,662. Subsequently, the contractor determined the contract, relying partly on the late repayment of the balance by the employer.

The appeal was conducted on the issue of whether the cancellation of the certificate of non-completion by the grant of an extension of time meant that the employer could no longer justify a deduction of LADs. The employer’s appeal was allowed. The judge stated that ‘If the conditions for the deduction of LADs from a payment certificate are satisfied at the time when the employer gives notice of intention to deduct, then the Employer is entitled to deduct the amount of LADs specified in the notice, even if the certificate of non-completion is cancelled by the subsequent grant of an extension of time.’ The employer must, however, repay the additional amount deducted within a reasonable time.

4.53 In Department of Environment for Northern Ireland v Farrans it was decided that the contractor has the right to interest on any repaid liquidated damages. This decision, however, was on JCT63 and, given that IC16 expressly refers to repayment without stipulating that interest is due, it would appear that interest would not be due in this situation. This was the view taken by His Honour Judge Carr in the first instance decision of Finnegan v Community Housing Association (1993) 65 BLR 103 (at page 114).

Department of Environment for Northern Ireland v Farrans (Construction) Ltd (1982) 19 BLR 1 (NI)

Farrans was employed to build an office block under JCT63. The original date for completion was 24 May 1975, but this was subsequently extended to 3 November 1977. During the course of the contract the architect issued four certificates of non-completion. By 18 July 1977, the employer had deducted £197,000 in liquidated damages but, following the second non-completion certificate, repaid £77,900 of those deductions. This process was repeated following the issue of the subsequent non-completion certificates. Farrans brought proceedings in the High Court of Justice in Northern Ireland, claiming interest on the sums that had subsequently been repaid. The court found for the contractor, stating that the employer had been in breach of contract in deducting monies on the basis of the first, second and third certificates, and that the contractor was entitled to interest as a result. The BLR commentary should be noted, which questions whether a deduction of liquidated damages empowered by clause 24.2 can be considered a breach of contract retrospectively. However, the case has not been overruled.

4.54 Certificates should always show the full amount due to the contractor. It is the employer alone who makes the deduction of liquidated damages. The employer would not be considered to have waived its claim by a failure to deduct damages from the first or any certificate under which this could validly be done, and would always be able to reclaim them as a debt at any point up until the final certificate.