9 Default and termination

9.1 Given the complexity and unpredictability of construction operations, it would be unlikely that a project could proceed to completion without breaches of the contractual terms by one party or another. This is recognised by most construction forms, which usually include provisions to deal with foreseeable situations. These provisions avoid arguments developing or the need to bring legal proceedings as the parties have agreed in advance machinery for dealing with the breach. A clear example of this is the provisions for liquidated damages – the contractor is technically in breach if the project is not completed by the contractual date, but all the consequences and procedures for dealing with this are set out in the contract itself. However, some breaches may have such significant consequences that the other party may prefer not to continue with the contract, and for these more serious breaches the contract contains provisions for terminating the employment of the contractor.

Repudiation or termination

9.2 In any contract, where the behaviour of one party makes it difficult or impossible for the other to carry out its contractual obligations, the injured party might allege prevention of performance and sue either for damages or a quantum meruit. This could occur in construction, for example, where the employer refuses to allow access to part of the site.

9.3 Where it is impossible to expect further performance from a party, then the injured party may claim that the contract has been repudiated. Repudiation occurs when one party makes it clear that they no longer intend to be bound by the provisions of the contract. This intention might be expressly stated, or implied by the party’s behaviour.

9.4 Most JCT contracts include termination clauses, which provide for the effective termination of the employment of the contractor in circumstances which may amount to, or which may fall short of, repudiation. It should be noted that the termination is of the contractor’s employment under the contract, and is not termination of the contract itself. This means that the parties remain bound by its provisions, and can bring actions for losses suffered through breach of its terms.

9.5 If repudiation occurs, it is unnecessary to invoke a termination clause, since the injured party can accept the repudiation and bring the contract to an end. However, the termination provisions are useful in setting out the exact circumstances, procedures and consequences of the termination of employment. These procedures must be followed with great caution because, if they are not administered strictly in accordance with the terms of the contract, this in itself could amount to a repudiation of the contract. This, in turn, might give the other party the right to treat the contract as at an end and claim damages.

9.6 Termination can be initiated by the employer in the event of specified defaults by the contractor, such as suspending the works or failing to comply with the Construction (Design and Management) (CDM) Regulations 2015 (cl 8.4) or in the event of the insolvency of the contractor (cl 8.5), or in cases of corruption or when certain circumstances relating to the Public Contracts Regulations 2015 apply (cl 8.6). Termination can be initiated by the contractor in the event of specified defaults by the employer, such as failure to pay the amount due on a certificate or where specified events result in the suspension of work beyond a period to be entered in the contract particulars (cl 8.9), or in the event of insolvency of the employer (cl 8.10). In the event of neutral causes, which bring about the suspension of the uncompleted works for the period listed in the contract particulars, the right of termination can be exercised by either party (cl 8.11).

Termination by the employer

9.7 The contract provides for termination by the employer under stated circumstances (cl 8.4). IC16 expressly states that the right to terminate the contractor’s employment is ‘without prejudice to any other rights and remedies’ (cl 8.3.1). Termination can be initiated by the employer in the event of specified defaults by the contractor occurring prior to practical completion (cl 8.4.1), the insolvency of the contractor (cl 8.5) or corruption (cl 8.6). Where the employer is a local or public authority, circumstances as set out in regulation 73(1)(b) of the Public Contracts Regulations 2015 (conviction of various offences) will also give rise to the right to terminate (cl 8.6).

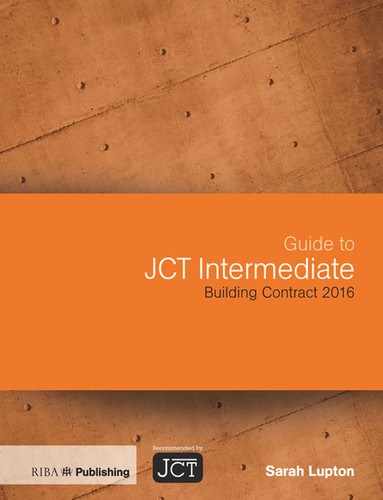

9.8 The procedures as set out in the contract must be followed exactly, especially those concerning the issue of notices (see Figure 9.1). If default occurs, the contract administrator should issue a warning notice of the ‘“specified” default or defaults’ (cl 8.4.1). If the default continues for 14 days from receipt of the notice, then the employer may terminate the employment of the contractor by the issue of a further notice within 21 days from the expiry of the 14 days (cl 8.4.2). If the contractor ends the default, or if the employer gives no further notice, and the contractor then repeats the default, the employer may terminate ‘within a reasonable time after such repetition’ (cl 8.4.3). The employer must still give a notice of termination, but no further warning is required from the contract administrator. There appears to be no time limit on the repetition of the default. If, however, a considerable period has elapsed, it may be prudent for the employer to issue a further warning notice before issuing the notice of termination.

9.9 It should be noted that, to be valid, all notices must be given strictly in accordance with clause 1.7.4, i.e. ‘by hand or sent by Recorded Signed for or Special Delivery post’ (cl 8.2.3). It should be noted that this is not the same as the older wording ‘actual delivery’, so it is unlikely that fax or email would be acceptable as in the case of Construction Partnership v Leek Developments. As the time limits are of vital importance, it is usually wise to have receipt of delivery confirmed.

Construction Partnership UK Ltd v Leek Developments Ltd [2006] CILL 2357 TCC

On an IFC98 contract, a notice of determination was delivered by fax, but not by hand or by special delivery or recorded delivery. (A letter had been sent by normal post but it was unclear whether or not it had been received.) Clause 7.1 required actual delivery of notices of default and determination, and the contractor disputed whether the faxed notice was valid. The court therefore had to decide what ‘actual delivery’ meant. It decided that it meant what it says: ‘Delivery simply means transmission by an appropriate means so that it is received’. In this case, it was agreed that the fax had been received, therefore the notice complied with the clause. The CILL editors state that ‘on a practical level, this judgement is quite important’ because it had previously been assumed that ‘actual delivery’ meant physical delivery by hand. In their view, email could be considered an appropriate method of delivery, although that was not decided in the case.

Figure 9.1 Termination by the employer

9.10 The grounds for termination by the employer must be clearly established and expressed. The contract clearly states that termination must not be exercised unreasonably or vexatiously (cl 8.2.1). Before issuing any notice the contract administrator should check, for example, that all extensions of time have been dealt with in accordance with the contract. Under clause 8.4.1.1 suspension of the work must be whole and substantial, and ‘without reasonable cause’. However, the contractor might find ‘reasonable cause’ in any of the matters referred to in clause 4.17. An exercise of the right to suspend work under clause 4.14 would not be cause for termination, provided that it had been exercised in accordance with the terms of the contract.

Specified defaults

9.11 The specified defaults which may give rise to termination are that the contractor:

- ‘wholly or substantially suspends the carrying out of the of the Works’ (cl 8.4.1.1);

- ‘fails to proceed regularly and diligently with the Works’ (cl 8.4.1.2);

- refuses or neglects to comply with a written instruction requiring the contractor to remove defective work (cl 8.4.1.3);

- fails to comply with clause 3.5 (sub-contracting), clause 3.7 (named persons) and clause 7.1 (assignment) (cl 8.4.1.4); or

- fails to comply with clause 3.18 (CDM Regulations) (cl 8.4.1.5).

9.12 Generally speaking, only a serious default would justify termination, although any failure to comply with the CDM Regulations’ provisions which would put the employer at risk of action by the authorities would be sufficient.

9.13 Clause 8.4.1.1 refers to suspension of the works, but it is interesting to note that although in SBC16 the clause adds ‘or the design of the Contractor’s Design Portion’ this phrase is not included in ICD16. This should not create a problem as, under the second recital, the works include the design and construction of the contractor’s designed portion, so any suspension of design activity is also a suspension of the works.

9.14 The default that the contractor ‘fails to proceed regularly and diligently’ (cl 8.4.1.2) is notoriously difficult to establish, and although meticulous records will help, contract administrators are often understandably reluctant to issue the first warning notice. It means more than simply falling behind any submitted programme, even to such an extent that it is quite clear the project will finish considerably behind time. However, something less than a complete cessation of work on site would be sufficient grounds.

9.15 In the case of London Borough of Hounslow v Twickenham Garden Developments, for example, the contract administrator’s notice was strongly attacked by the defendants. In a more recent case, however, the contract administrator was found negligent because it failed to issue a notice (West Faulkner Associates v London Borough of Newham). It should be remembered that without the first ‘warning notice’ issued by the contract administrator the employer cannot issue the termination notice.

London Borough of Hounslow v Twickenham Garden Developments (1970) 7 BLR 81

The London Borough of Hounslow entered into a contract with Twickenham Garden Developments to carry out sub-structure works at Heston and Isleworth in Middlesex. The contract was on JCT63. Work on the contract stopped for approximately eight months due to a strike. After work resumed, the architect issued a notice of default stating that the contractor had failed to proceed regularly and diligently and that, unless there was an appreciable improvement, the contract would be determined. The employer then proceeded to determine the contractor’s employment. The contractor disputed the validity of the notices and the determination, and refused to stop work and leave the site. Hounslow applied to the court for an injunction to remove the contractor. The judge emphasised that an injunction was a serious remedy and that, before he could grant one, there had to be clear and indisputable evidence of the merits of Hounslow’s case. The evidence put before him, which showed a significant drop in the amounts of monthly certificates and numbers of workers on site, failed to provide this.

West Faulkner Associates v London Borough of Newham (1992) 61 BLR 81

West Faulkner Associates were architects engaged by the London Borough of Newham for the refurbishment of a housing estate consisting of several blocks of flats. The residents of the estate were evacuated from their flats in stages to make way for the contractor, Moss, which, it had been agreed, would carry out the work according to a programme of phased possession and completion, with each block taking nine weeks. Moss fell behind the programme almost immediately. However, Moss had a large workforce on the site and continually promised to revise its programme and working methods to address the problems of lateness, poor quality work and unsafe working practices that were drawn to its attention on numerous occasions by the architect. In reality, Moss remained completely disorganised, and there was no apparent improvement. The architect took the advice of quantity surveyors that the grounds of failing to proceed regularly and diligently would be difficult to prove, and decided not to issue a notice. As a consequence, Newham was unable to issue a notice of determination, had to negotiate a settlement with the contractor and dismissed the architect, which then brought a claim for its fees.

The judge decided that the architect was in breach of contract in failing to give proper consideration to the use of the determination provisions. In his judgment, he stated that ‘regularly and diligently’ should be construed together and in essence they mean simply that the contractors must go about their work in such a way as to achieve their contractual obligations. ‘This requires them to plan their work, to lead and manage their workforce, to provide sufficient and proper materials and to employ competent tradesmen, so that the Works are carried out to an acceptable standard and that all time, sequence and other provisions are fulfilled’ (Judge Newey at page 139).

Insolvency of the contractor

9.16 Insolvency is the inability to pay debts as they become due for payment. Insolvent individuals may be declared bankrupt. Insolvent companies may be dealt with in a number of ways, depending upon the circumstances: for example, by voluntary liquidation (in which the company resolves to wind itself up); compulsory liquidation (under which the company is wound up by a court order); administrative receivership (a procedure to assist the rescue of a company under appointed receivers); an administration order (a court order given in response to a petition, again with the aim of rescue rather than liquidation, and managed by an appointed receiver); or voluntary arrangement (in which the company agrees terms with creditors over payment of debts). IC16 sets out a full definition of the term ‘Insolvent’ for the purposes of the contract at clause 8.1. Procedures for dealing with insolvency are mainly subject to the Insolvency Act 1986 and the Insolvency Rules 2016 (in place from April 2017). Under these provisions, the person authorised to oversee statutory insolvency procedures is termed an ‘insolvency practitioner’.

9.17 Under IC16, the contractor must notify the employer in writing in the event of liquidation or insolvency (cl 8.5.2). The employer is given an option to terminate (cl 8.5.1) or to consider a more constructive approach. This is to allow the appointed insolvency practitioner time to come up with a rescue package, if possible. It is usually in the employer’s interest to have the works completed with as little additional delay and cost as possible, and a breathing space might allow all possibilities to be explored. During this period, the contract states that ‘clauses 8.7.3 to 8.7.5 and (if relevant) clause 8.8 shall apply as if such notice had been given’ (cl 8.5.3.1). This means that even if no notice of termination is given, the employer is under no obligation to make further payment except as provided under those clauses (see paragraph 9.24). The contractor is relieved of the obligation to ‘carry out and complete the Works’ (cl 8.5.3.2). The employer may then take reasonable steps to ensure that the site, works and materials are secure and protected, and the contractor may not hinder such measures (cl 8.5.3.3).

9.18 There are three options for completing the project. The first allows for arrangements to be made for the contractor to continue and complete the works. Unless the insolvency practitioner has been able to arrange resource backing, this may not be a realistic option. If practical completion is near, however, and money is due to the contractor, it can be advantageous to allow completion under the control of the insolvency practitioner.

9.19 Under the second option, another contractor may be novated to complete the works. On a ‘true novation’, the substitute contractor takes over all the original obligations and benefits (including completion to time and within the contract sum). More likely is the third option, ‘conditional novation’, whereby the contract completion date, etc. would be subject to renegotiation, and the substitute contractor would probably want to disclaim liability for that part of the work undertaken by the original contractor.

9.20 Deciding on which of the options would best serve the interests of all the parties is a matter to be resolved by the employer, with advice from the contract administrator and the insolvency practitioner. There might be merit in adopting one particular course of action, or there might be advantages in taking a more pragmatic approach. For example, it may prove expeditious to continue initially with the original contractor under an interim arrangement until such time as novation can be arranged or a completion contract negotiated.

Consequences of termination

9.21 If the employer exercises its right to terminate under clause 8.4, 8.5 or 8.6, then the only way to achieve completion will be through the appointment of a new contractor of the employer’s choice. The contract gives the employer the right to employ others under clause 8.7.1 to complete the works. This would include making good any defects in the work already carried out and, in the case of ICD16, to complete the designed portion. The employer will have the right to use any temporary buildings, plant, etc. on site which are not owned by the original contractor, subject to the consent of the owner (cl 8.7.1).

9.22 The employer may also require the contractor to:

- remove from the site any temporary buildings, plant, etc. which are owned by the contractor (cl 8.7.2.1);

- provide the employer with copies of all contractor’s design documents (cl 8.7.2.2, ICD16 only);

- require the original contractor to assign the benefit of any sub-contracts to the employer (to the extent that the benefit is assignable) (cl 8.7.2.2, cl 8.7.2.3 in ICD16).

9.23 If the employer decides to employ others under clause 8.7.1, such employment must be handled with care, as completion of a building started by another contractor is always difficult. A completion contract might result from negotiation or competitive tender, but the tender route may be advisable if there is much to complete as the employer may have to demonstrate subsequently that the costs incurred were reasonable. A record should be made of the exact state of completeness at the time of termination, including any defective work.

9.24 Following termination, clause 8.7.3 states that ‘no further sums shall become due to the Contractor … other than any amount that may become due to him under clause 8.7.5 or 8.8.2’. It also states that the employer will not need to make any payments that have already become due to the extent that a pay less notice has been given (cl 8.7.3.1) or where the contractor has become insolvent (cl 8.7.3.2). This reflects section 111(10) of the HGCRA as amended, and the judgment in Melville Dundas v George Wimpey. It should be noted, however, that the employer may still be obliged to pay amounts awarded by an adjudicator (Ferson v Levolux).

Melville Dundas Ltd v George Wimpey UK Ltd [2007] 1 WLR 1136 (HL)

On a contract let on WCD98, the contractor had gone into receivership, entitling the employer to determine the contractor’s employment. The contractor had applied for an interim payment on 2 May 2003, the final date for payment was 16 May (14 days after application), and the determination was effective on 30 May. The contractor claimed the payment on the basis that no withholding notice had been issued. By a majority of three to two, the House of Lords decided that the employer was not obliged to make any further payment. It was accepted that, under WCD98, interim payments were not contractually payable after determination and the House of Lords held that this was not inconsistent with the payment provisions of the HGCRA 1996. Although the Act requires that the contractor should be entitled to payment in the absence of a notice, this did not mean that that entitlement had to be maintained after the contractor had become insolvent, i.e. it was not inconsistent to construe that the effect of the determination was that the payment was no longer due. The Act was concerned with the balance of interests between payer and payee, and to construe it otherwise would give a benefit to the contractor’s creditors against the interests of the employer, something which the Act did not intend.

Ferson Contractors Ltd v Levolux AT Ltd [2003] BLR 118

Ferson was the contractor and Levolux the sub-contractor on a GC/Works sub-contract. A dispute arose regarding Levolux’s second application for payment; £56,413 was claimed but only £4,753 was paid. A withholding notice was issued which specified the amount but not the reason for withholding it. Levolux brought a claim to adjudication, and the adjudicator decided that the notice did not comply with section 111 of the HGCRA 1996, and that Ferson should pay the whole amount. Ferson refused to pay and Levolux sought enforcement of the decision. Prior to the adjudication, Levolux had suspended work and Ferson, maintaining that the suspension was unlawful, had determined the contract. It now maintained that, due to clause 29, which stated that ‘all sums of money that may be due or accruing due from the contractor’s side to the subcontractors shall cease to be due or accrue due’ they did not have to pay this amount. The CA upheld the decision of the judge of first instance that the amount should be paid: ‘The contract must be construed so as to give effect to the intent of Parliament’.

9.25 Following termination, a notional final account must be set out, stating what is owed or owing, either in a statement prepared by the employer or in a contract administrator’s certificate (cl 8.7.4). This account must be prepared within three months of ‘the completion of the Works and the making good of defects in them’, which allows the employer a period to assess its losses due to the termination. The net amount shown on the account should be paid by the contractor to the employer (the more likely outcome), or by the employer to the contractor, as appropriate (cl 8.7.5).

9.26 One of the consequences of termination is that it often takes time for the contractor to effect an orderly withdrawal from site, and for the employer to establish the amounts outstanding before final payment. Should the employer decide not to continue with the construction of the works after termination, the employer is required to notify the contractor in writing within six months of that notice (cl 8.8). Within two months of the notification (or within six months of termination, if no work is carried out and no notice issued) the employer must send the contractor a statement of the value of the works and losses suffered as required under clause 8.8.

Termination by the contractor

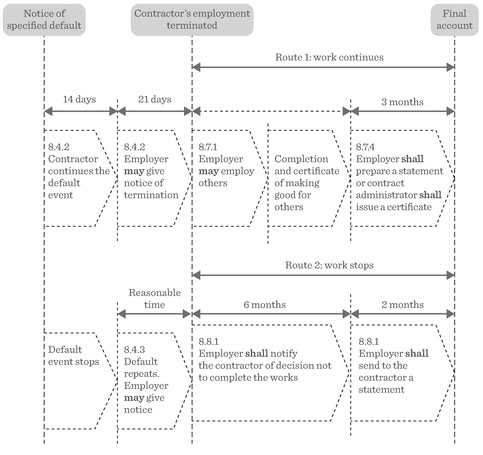

9.27 The contractor has a reciprocal right under clause 8.9 to terminate its own employment in the event of specified defaults of the employer (cl 8.9.1), or specified suspension events (cl 8.9.2) or insolvency of the employer (cl 8.10). The specified suspension events must have resulted in the suspension of the whole of the uncompleted works for the continuous period stated in the contract particulars (if no period is entered the default period is two months). In the case of specified defaults or suspension events a notice is required, which must specify the default or event. If the default or event continues for 14 days from receipt of the notice, the contractor may terminate the employment by a further notice up to 21 days from the expiry of the 14 days (cl 8.9.3) (see Figure 9.2). Alternatively, if the employer ends the default or the suspension event ceases, and the contractor gives no further notice, should the employer repeat the default the contractor may terminate ‘within a reasonable time after such repetition’ (cl 8.9.4). These notices must be given by the means set out in clause 1.7.4, i.e. ‘by hand or sent by Recorded Signed for or Special Delivery post’ (cl 8.2.3).

9.28 The grounds of clause 8.9 differ from those that give the employer the right to terminate. They comprise failure to pay an amount properly due to the contractor in accordance with clause 4.12 (cl 8.9.1.1), obstruction of the issue of a certificate (cl 8.9.1.2), failure to comply with the contractual provisions relating to assignment under clause 7.1 (cl 8.9.1.3) or with CDM obligations under clause 3.18 (cl 8.9.1.4). There are also matters which relate directly to the duties of the contract administrator, where, for example, the carrying out of the whole or substantially the whole of the works is suspended as a consequence of an instruction relating to inconsistencies, variations or postponement (cl 8.9.2.1), or due to any ‘impediment, prevention or default’ of the employer or contract administrator (cl 8.9.2.2), but only if the instruction or default was not necessitated by some negligence or default of the contractor. The period of suspension is two months unless some other period is stated. In long and complex projects two months may not be sufficient should unexpected technical problems arise, therefore it may be advisable to consider inserting a longer period.

Figure 9.2 Termination by the contractor

9.29 The contractor should exercise particular care if considering termination due to what it considers to be an employer’s failure to pay. The contract specifically requires failure to pay ‘the amount due’ (cl 8.9.1.1), and not simply the amount for which the contractor might have applied. If the contractor has made an error in its calculations, the employer might be entitled to pay a lesser amount. In addition, the contract gives the employer rights to make various adjustments to and deductions from amounts due. The correct exercise of these rights would not amount to a failure to pay an amount due. If the contractor attempts to terminate its employment without justification, this will amount to repudiation, with serious consequences for the contractor. A more prudent course would be to raise the disputed payment in adjudication, while continuing to proceed with the works.

9.30 Termination by the contractor is optional in the case of the employer’s bankruptcy or insolvency (cl 8.10.1). The contractor must issue a notice and termination would take effect from the receipt of the notice.

Consequences of termination by the contractor

9.31 Following termination under clause 8.9 or 8.10, the contract states that no further sums become due to the contractor otherwise than provided for by that clause (cl 8.12.1). The contractor is required to remove tools etc. from the site and, in the case of ICD16, to provide the employer with a copy of the ‘As-built Drawings’ referred to in clause 2.32 (e.g. contractor’s design documents and related information) (cl 8.12.2). The contractor then prepares an account as soon as is reasonably practicable setting out the total value of the work at the date of termination, plus other costs relating to the termination as set out in clause 8.12.3. These may include such items as the cost of removal and any direct loss and/or damage consequent upon termination. The contractor is, in effect, indemnified against any damages that may be caused as a result of the termination.

Termination by either the employer or the contractor

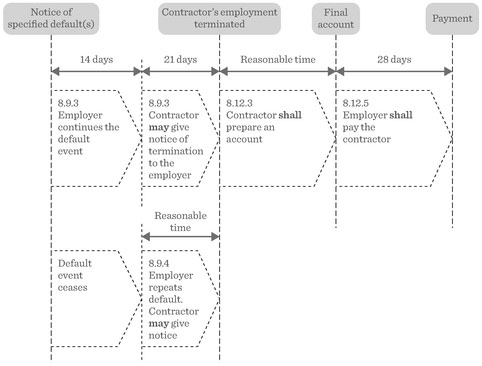

Figure 9.3 Termination by either party

9.32 Either party has the right to terminate the contractor’s employment if the carrying out of the works is wholly or substantially suspended for the period inserted in the contract particulars by one or more of the events listed in clause 8.11.1 (if no period is entered the default period is two months). These events include force majeure, loss or damage to the works caused by any risk covered by the works insurance policy or by an excepted risk, civil commotion and the exercise by the government or a local or public authority of a statutory power not occasioned by the default of the contractor. The right of the contractor to terminate in the event of damage to the works is limited by the proviso that the event must not have been caused by the contractor’s negligence (cl 8.11.2). In addition, either party may terminate if work is suspended because of an employer’s instruction under clause 2.15 (divergences), clause 3.11 (variations) or clause 3.12 (postponement) which has been issued as a result of negligence or default of a statutory undertaker (cl 8.11.1.2).

9.33 Notice may be given by either party and the employment of the contractor will be terminated seven days after receipt of the notice, unless the suspension ceases within seven days after the date of the receipt of that notice. If the cessation does not stop after this period, the party may then, by further notice, terminate the contract (cl 8.11.1, see Figure 9.3). Where the employer is a local or public authority, the employer may issue a notice if circumstances in regulation 73(1)(a) or (c) of the Public Contracts Regulations 2015 (various breaches of the Regulations) apply (cl 8.11.3). This appears to effect an immediate termination.

9.34 Following termination, clauses 8.12.1 (no further sums become due) and 8.12.2 (removal of tools etc. and, in the case of ICD16, supply of as-built drawings) apply. An account is then prepared in the same format as for termination by the contractor (cl 8.12.3, see paragraph 9.24), except that in this case amounts relating to direct loss and/or damage caused to the contractor are only included where they result from a specified peril caused by the employer’s negligence.

Termination of the employment of a named sub-contractor

9.35 The contractor is responsible for taking action with respect to termination of the employment of named sub-contractors. The contract states that the employment of a named sub-contractor must not be terminated other than through the operation of clauses 7.4 to 7.6 of ICSub/NAM/C, and that the contractor must not bring the sub-contract to an end through acceptance of the repudiation of the sub-contract (Schedule 2:6). The reason for this requirement is that, once the named sub-contract has been terminated, the contractor is required to take steps to recover from the sub-contractor any additional amounts payable to the contractor by the employer as a result of the termination (Schedule 2:10.2.1). If the contractor has not followed the provisions of the sub-contract exactly, the chances of recovery of these losses would be greatly reduced.

9.36 The contractor must advise the contract administrator of any events which might give rise to termination of the named sub-contract. In some circumstances this may give the contract administrator the opportunity to make some investigations and assess in advance the possible alternative courses of action should termination occur.

9.37 The contractor must notify the contract administrator as soon as the contract has been terminated. The contract administrator must then issue instructions which may either name another person to execute the work, require the contractor to complete the work or omit the outstanding work (Schedule 2:7). The consequences of the termination then depend on whether the sub-contractor was originally named in the contract documents, contract bills/specification/work schedules, or named in an instruction relating to a provisional sum.

9.38 If the sub-contractor was originally named in the tender documents, then an instruction naming a replacement is treated as an event which may be grounds for an extension of time, but not as a matter giving rise to direct loss and/or expense (Schedule 2:8.1). The contract sum is to be adjusted by the difference between the price of the first named sub-contractor for the outstanding work and the price of the replacement, although any amounts in the price of the replacement sub-contractor which cover the correction of defective work are not to be added to the contract sum. The effect of this is that the contractor remains responsible for any defective work carried out by the original named person. An instruction omitting the work, or requiring the contractor to carry out the work, is treated as a variation under clause 5.3, and an event which may give rise to an extension of time and to an award of direct loss and/or expense.

9.39 If the termination relates to a sub-contractor named under an instruction relating to a provisional sum, then the contract administrator’s instruction is treated as a further instruction under the provisional sum, and therefore one which may give rise to an adjustment of the contract sum, an extension of time and to an award of direct loss and/ or expense (Schedule 2:9). The contract administrator should be careful not to delay unreasonably in issuing instructions following a termination, as this could also be grounds for a claim for extension of time under clause 2.20.2.1, direct loss and/or expense under clause 4.18.2.1 and, under exceptional circumstances, could even lead to termination under clause 8.11.1.2.

9.40 If the employment of a named sub-contractor is terminated other than in accordance with the contractual provisions, then the contract administrator is still required to issue instructions as described above, but the contract states that these will not result in any right to an extension of time or to direct loss and/or expense, and that no adjustment will be made to the contract sum except if application of the contractual provisions would result in a reduction (Schedule 2:10). The effect of this is to place the entire risk of the consequences of such a termination on the shoulders of the contractor.