Chapter 1

The Importance of Unsupervised Individual Learning in Education

Abstract

This chapter introduces the key concepts of the book and provides context for the experimental work to be reported in later chapters. First, we discuss the importance of unsupervised individual learning in education and the importance of homework. A brief history of homework in American education, from the early 19th century to the present, is presented. The development of homework as a standard part of formal education is reviewed, and the recurring issues in favor of and against homework are discussed. The relationship of unsupervised individual learning to supervised group learning and the relationship of unsupervised individual learning to homework are discussed.

Keywords

History of homework; Homework; Supervised group learning; Supervised learning; Unsupervised individual learning; Unsupervised learning

When you think of education, it is likely that you think about formal school situations that you have experienced. Perhaps you recall your teachers, your classmates, the subject-matter categories, or discussions and other interactions in classes with teachers and with other students. Maybe you remember a group project that was interesting or fun or challenging. You may recall the physical arrangement of the school buildings, the processes of starting and ending the school day, or special events such as sports or music performances. It is less likely that the first thing that comes to mind is the independent studying that most likely absorbed many hours, especially in the later years of your education. This study time and effort, however, is typically a vitally important part of your education. There are, of course, a variety of ways to study, including team projects, study groups, and so forth. The dominant study situation, however, is unsupervised individual learning, usually referred to as homework.

The Importance of Homework

Homework serves many important functions for learning. It allows students to review new concepts, ideas, and terminology. It prescribes specific practice. It may allow for thoughtful complex thinking that can only be accomplished over more time than is available in classes. It provides the time necessary for mastery learning. And it can even be thought of as a rudimentary form of individualized instruction where a student can approach a topic at his or her own pace and in a preferred fashion.

Homework becomes increasingly important as students progress from elementary school, to middle school, to high school, and finally, to college. Some high school students may spend about 5

hours in classroom instruction (e.g., six or seven 45-minute classes), followed by 2–3

hours of evening homework. Thus, about one-third of all learning time may be spent doing homework. By college, this ratio is typically reversed, with at least

two-thirds of all learning time spent outside the classroom. Beyond college, this trend continues. Some forms of adult learning, such as Internet-based “continuing education” and “lifelong learning,” may be almost entirely unsupervised individual study with characteristics similar to school-assigned homework. For these reasons, knowledge of how to design effective, efficient, interesting, and cost-effective homework should be of primary importance to educators.

A Brief History of Homework in American Education

During the first half of the 19th century, elementary school students had little or no homework, in part because of their teachers' heavy workload. In the 1830s, Chicago city classrooms might include as many as 100 students, with older students assigned to direct the instruction for small groups (Herrick, 1971; Kaestle, 1973). In rural one-room schools, one teacher taught all subjects to students who might range in age from 6 to 14

years (Fuller, 1982). Most students left school after fourth grade, but those who moved on to grammar school (grades 5–8) received 2–3

hours of homework each night during the week. The even smaller number of students who earned a high school diploma completed homework on weekends as well (Reese, 1995).

After the Civil War, public funding for schools increased, and students completed more years of school. As homework was assigned more frequently, conflicts arose between parents and schools (Kaestle, 1978). In 1880, the president of the Boston school board complained that his children's arithmetic homework was not useful for learning and interfered with their physical, mental, and emotional health. The school board responded by limiting the amount of arithmetic homework that teachers could assign (Burnham, 1905).

In the 1890s, anti-homework sentiments grew more prevalent and more extreme. Doctors warned that homework was damaging to children's eyesight and interfered with healthy outdoor exercise. Magazines and newspapers criticized homework for robbing children of the time they needed for play, for sleep, for chores, for church attendance, and for the moral influence of their parents. School officials felt that distractions at home actually interfered with children's learning, and many schools replaced homework in grades 4–6 with 15–30

minute in-school study periods (Annual Report of the Board of Education of Los Angeles, 1902). By 1901, a Massachusetts investigator reported that assigning homework was restricted in two-thirds of the city school districts surveyed (Gill & Schlossman, 1996).

During World War I, conflicts over homework quieted, but as the war ended, parents again became concerned about homework's negative effects on their children. The popular press resumed its criticisms, describing homework as a threat to children's health and as an unfair labor practice (Bassett, 1934). In 1919, the Progressive Education Association was founded to change education by making it an individualized process of discovery. The teacher's role was to provide experiences that would guide each child toward positive growth. Progressives believed that homework could interfere with engaging in real-life tasks and community activities (Graham, 1967; Westbrook, 1991).

By the 1940s, a majority of schools in the United States had adopted the progressive approach and had eliminated or stringently limited homework. But during this time, members of a “homework reform movement” suggested that a different kind of homework could support the goals of progressive education. They recommended a new focus on hands-on activities, projects, and home and community experiences. Parents could help children participate in music, art, sports and physical endeavors, cooking, helping with the family budget, interior decorating, and other pursuits that children would value and enjoy (Andersen, 1940; Eginton, 1931).

These ideas were surprisingly well received by a majority of parents (Gill & Schlossman, 2003a), and schools made more effort to individualize homework assignments to match the abilities and interests of each student. Nevertheless, many school districts instituted homework policies to limit the amount of time spent on homework, in accordance with a student's age and grade level. Generally, no homework was assigned for early elementary students. Junior high students could be assigned up to an hour of homework four nights a week, and high school students were limited to an hour and a half four nights per week (Strang, 1955). A number of schools chose not to assign homework on the weekend so students would have this time for personal activities and relief from the school work week (Olson, 1962). By 1948, a Purdue Opinion Poll reported that most high school students were doing less than an hour of homework per day (Gill & Schlossman, 2004).

The Russians' launch of Sputnik in 1957, however, caused many parents and educators to question the quality of American education. Russia's apparent superiority in science and mathematics education was contrasted with an American curriculum that was criticized for having too many courses focused on life skills and for failing to challenge gifted students (Herold, 1974). To help the United States compete with Russia, courses of study became more rigorous, and the amount of homework was increased.

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, homework was once again criticized as a danger to the health and wellbeing of young people, and some school districts responded accordingly (Vatterott, 2018). According to the Purdue Opinion Poll, the number of high school students doing more than 2

hours of daily homework fell from approximately 20% to 9% between 1967 and 1972 (Gill & Schlossman, 2003a). But with the publication of A Nation at Risk (United States National Commission on Excellence in Education, 1983) and What Works (United States Department of Education, 1986), homework returned to favor (Gill & Schlossman, 2003b). These reports caused widespread concern that American schools were lax and ineffective in preparing students to compete with students in other countries (Cooper, 2001; Gill & Schlossman, 2003a, 2004).

More than 30

years later, homework remains an often discussed and frequently controversial aspect of school policy. As in the past, many school systems have developed homework policies that outline the amount of time students should spend on homework. Particularly in elementary school, some school districts have eliminated or imposed strict limits on homework and have tried to bring most learning into the classroom (e.g., Hough, 2012; Vail, 2001). On the other hand, in response to national achievement standards, districts have established homework policies for a variety of other purposes, including improving basic skills and raising scores on standardized tests. Student failure is often blamed on not doing homework (e.g., Rauch, 2004), and at the other extreme, student stress and failure are sometimes considered to be the result of too much homework (Abeles, 2015; Galloway, Conner, & Pope, 2013; Resmovits, 2014). The entire efficacy of homework as an educational practice has been questioned in the popular press, in periodicals (e.g., Time: Ratnesar, 1999; Reilly, 2016; The Wall Street Journal: Hobbs, 2018; Keates, 2007), and in books (e.g., Bennett & Kalish, 2006; Cooper, 2007; Horsley & Walker, 2013; Kohn, 2006; Kralovec & Buell, 2000; Rosemond, 1990; Vatterott, 2018).

In recent years, a number of the anti-homework articles and stories that have been publicized in newspapers, magazines, and social media have claimed that today's students are overwhelmed with hours of homework. Yet the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) shows that from 1984 to 2012, the overall homework load for children at ages 9, 13, and 17

years remained stable for 17-year-olds and decreased for 13-year-olds. The only increase was among 9-year-olds where the percentage of those with some homework increased from 65% in 1984 to 78% in 2012. The percentage of students in each age group reporting more than 2

hours of homework a night in 2012 was 5% for 9-year-olds (6% in 1984), 7%

for 13-year-olds (9% in 1984), and 13% for 17-year-olds (13% in 1984) (Brookings Institution, 2014, pp. 18–21).

Two other surveys provide reliable information about how much time per week students spend on homework. In 2002–03, the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan continued its studies of a representative sample of 2,907 children and adolescents to learn how the nation's young people spend their time. The following list shows the time per week that different age groups spent on study in 2002–03: 6–8

years—2

hours, 33

minutes; 9–11

years—3

hours, 36

minutes; 12–14

years—4

hours, 40

minutes; 15–17

years—4

hours, 59

minutes. The average time for all ages was 3

hours, 58

minutes, as compared with 2

hours, 38

minutes in 1981–82 (Juster, Ono, & Stafford, 2004). So although time spent on study had increased in this 20-year interval, all weekly averages seem within reasonable limits. An annual survey of college freshmen, reported by the Higher Education Research Institute of UCLA, found a decrease in total study time among high school seniors. Fewer college freshmen reported studying more than 6

hours per week during the senior year of high school. Although 49.5% reported studying this much in 1986, only 38.4% of students gave this response in 2012 (Pryor et al., 2012).

Numerous newspaper and magazine articles, as well as television news features, have given the impression that the majority of parents are opposed to homework. Such reports are almost always based on interviews with only a few parents or on anecdotes from a small number of school personnel. In contrast, large-scale surveys do not support this conclusion. For example, a Met Life Survey “Parents' View of the Homework Load 2007” shows that 60% of parents feel schools are giving the “Right Amount” of homework, 25% feel that there is “Too Little” homework, and 15% feel that there is “Too Much” homework (Met Life, 2007). Similarly, a 2010 Chicago Tribune survey of local parents found parallel results in which about two-thirds of parents said the homework load was “about right,” 21% said it was “not enough,” and 12% responded that it was “too much” (Brookings Institution, 2014, pp. 18–21).

As in previous years, the primary conflicts about homework are about time. On the one hand, more time is recommended to improve student achievement. On the other hand, less time is recommended to reduce student stress and to open opportunities for other after-school activities, ranging from sports to youth organizations to vocational training jobs. Although everyone can measure time, most people know very little about the qualitative aspects of homework that promote interest, pleasure, or effectiveness. Consequently, local school boards seldom focus on how to make homework more

interesting, more enjoyable, or more productive: the design of homework is seldom discussed.

A similar point can be made about the psychological research on homework. Although there is a vast literature on learning, how students learn, and recommendations for teaching, a survey of the literature on homework shows little work aimed specifically at relating the design of homework to particular cognitive processes. For example, a special issue of Educational Psychologist (Cooper & Valentine, 2001) included topics relating to homework research and homework policy (Cooper & Valentine, 2001), students' opinions about homework (Warton, 2001), special problems of learning disabled students in doing homework (Bryan, Burstein, & Bryan, 2001), various purposes of homework and parental involvement (Epstein & Van Voorhis, 2001; Hoover-Dempsey et al., 2001), and after-school programs for homework assistance (Cosden, Morrison, Albanese, & Macias, 2001). All of these topics are important for education, but missing from the mix is a focused discussion of homework design from the points of view of cognitive effectiveness and efficiency.

Although relatively few homework studies have evaluated the learning benefits of specific cognitive processes, many have attempted to quantify the overall learning benefits of performing homework. Cooper (1989) analyzed 11 reviews of the effects of homework on achievement. Of these 11 reviews, conducted between 1950 and 1987, five concluded that homework had a generally positive effect on achievement (Austin, 1979; Goldstein, 1960; Keith, 1986, 1987; Paschal, Weinstein, & Walberg, 1984), but six determined that no conclusion could be drawn (Coulter, 1979; Friesen, 1979; Harding, 1979; Knorr, 1981; Marshall, 1983; Otto, 1950). More recently, Cooper, Robinson, and Patall (2006) reviewed research reported from 1987 to 2003 and concluded that most of these studies found positive relationships between the amount of homework completed and student achievement. Subsequently, Hattie (2009) reviewed five meta-analyses of homework and achievement that involved 161 studies and more than 100,000 students. This review concluded that homework produced positive effects about 65 percent of the time.

Given the various research results, it is obvious that sometimes homework is beneficial, and sometimes it is not. We hypothesize that the explanation for this variability is largely due to the design of the homework. Our work focuses on the cognitive processes elicited when homework is designed to include specific learning activities that we are calling cognitive events, and one of our goals is to identify cognitive events that make homework more effective.

In spite of the ongoing debate about the value of homework, it will not disappear. In fact, because of the increasing needs of adults to continue learning in order to maintain employment, individual study is likely to continue to increase. The advent of the Internet age serves as a huge multiplier of this likelihood. Clearly, it is extremely important that homework be well designed and useful.

The Relation of Unsupervised Individual Learning to Supervised Group Learning

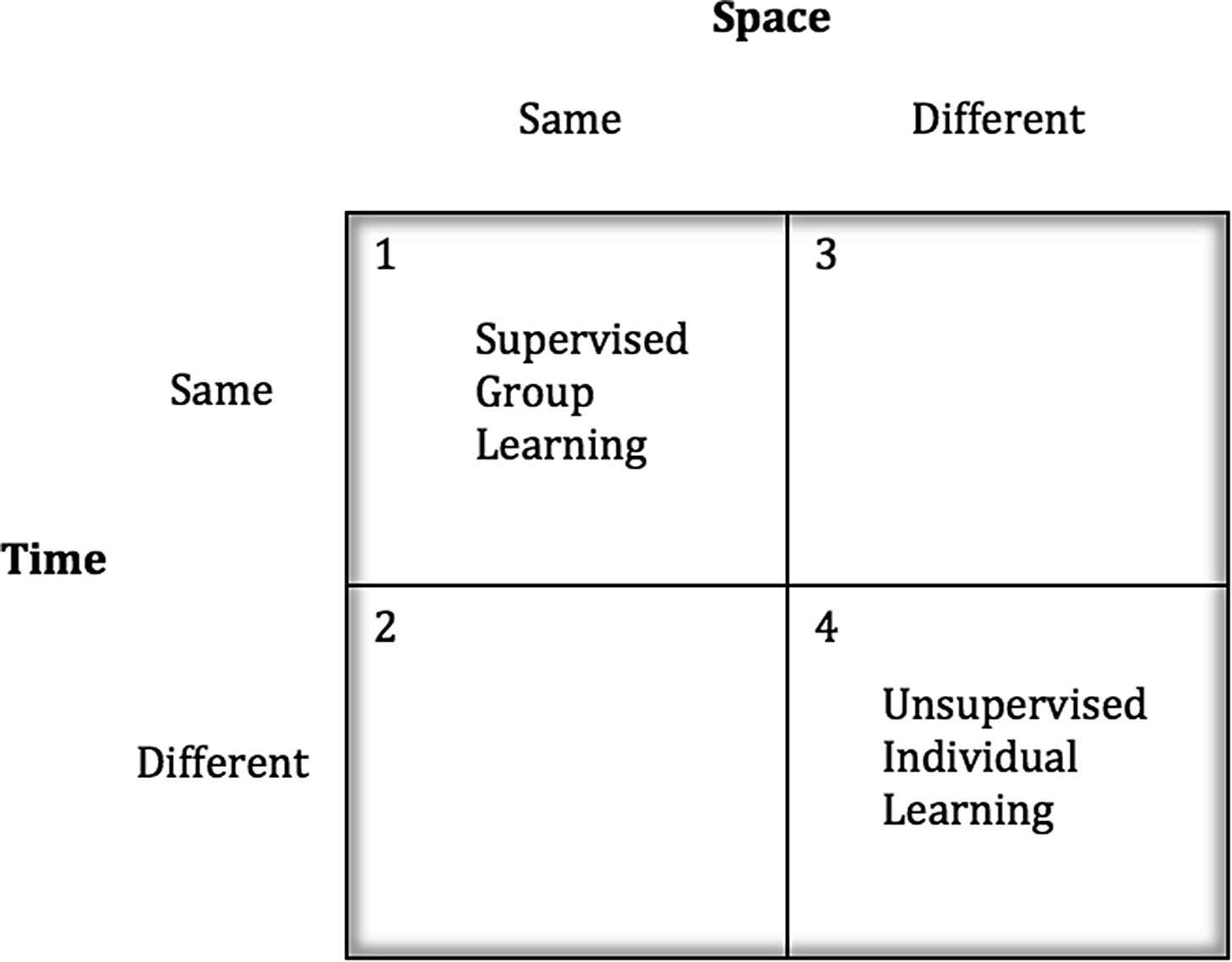

Consider the space-time matrix shown in Figure 1.1 that has been used by many researchers to classify conditions of work in studies of computer-supported cooperative work (e.g., Whitten, 2001), as well as conditions of learning in studies of computer-supported cooperative learning.

Applying this matrix to student learning clarifies the contrast of greatest interest for our research. Cell 1, labeled Supervised Group Learning, includes the supervised classroom where students, teachers, and information coexist in space and time. Commonly, classroom learning is (1) supervised, (2) group-based, (3) teacher-paced, (4) social, (5) interactive, and (6) occurs in a formal learning environment. Under these conditions, cognitive processes can be heavily influenced by teachers and classmates. Such organized learning activities have been found to increase students' interest and

motivation (Anderson, Hamilton, & Hattie, 2004; Renninger, Hidi, & Krapp, 2014; Schraw, Flowerday, & Lehman, 2001), to be highly memorable (Boling & Robinson, 1999; Fraser, 2015), and to be likely to elicit cognitive, affective, and social processes that contribute to comprehension and retention (Ainley, 2006; Guz & Tetiurka, 2016; Shernoff, 2013).

In contrast, Cell 4, labeled Unsupervised Individual Learning, includes learning activities that, unless mediated by technology, are solitary and include most study commonly referred to as homework.

1

Such learning is generally (1) unsupervised, (2) individual, (3) self-paced, (4) solitary, (5) self-monitored, and (6) occurs in an informal learning environment. Under these conditions, cognitive processes are primarily determined by the requirements of the homework questions and tasks.

The attributes of supervised group learning and unsupervised individual learning are summarized in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1

The Relation of Unsupervised Individual Learning and Homework

Most, but not all, homework is unsupervised individual learning. A large proportion of unsupervised individual learning, but not all, is homework. The relation of unsupervised individual learning and homework is illustrated in Figure 1.2. The larger circle represents all forms of unsupervised individual learning, and the smaller circle represents all forms of homework. The intersection of the two circles represents homework that is also unsupervised individual learning.

During the years of formal education, homework is primarily unsupervised individual learning, but several other important types of homework are also represented in Figure 1.2 by the non-overlapping portion of the smaller circle. These more supervised and interactive types of homework include group projects and various sorts of cooperative learning situations, as well as community-based activities such as conducting interviews with people in the community and participating in local service projects. Technology-based homework may occur as unsupervised individual

learning, but this type of homework may also include real-time interaction of students, primarily through computers, to share text, audio, or video, thus providing some of the characteristics of supervised group learning. Another important type of homework that has characteristics of supervised group learning includes the use of intelligent-tutoring systems where students interact with programmed intelligence to receive hints, feedback, or scores as they learn.

The non-overlapping portion of the larger circle in Figure 1.2 represents many unsupervised individual learning situations in addition to those associated with formal schooling. These include adult study at work and online to maintain and advance work-related skills, and also non-work learning motivated by avocations, travel, family activities, and membership in organizations. Other examples of unsupervised individual learning situations include study for licenses and certifications required for work or leisure activities.

Some of the characteristics listed for unsupervised individual learning can be cited as advantages of Internet-based and other technology-based instruction because they can provide the convenience of anytime-anywhere learning. These characteristics may be disadvantages, however, if the unsupervised learning environment fails to include effective cognitive events that are common in supervised learning environments. We hypothesize that unsupervised individual learning conditions (homework or otherwise) are often impoverished, compared to the more structured, social, interactive learning environments represented in Cell 1 of Figure 1.1. We further hypothesize that unsupervised individual learning may be made more effective by designing tasks with attributes of supervised group learning. If so, the identification and incorporation of cognitive events that elicit learning-effective cognitive processes will provide significant practical advantages to teachers and other designers of homework as a means to make learning from homework more effective.

The primary focus of this book is the large proportion of homework that consists of unsupervised individual learning. Many of the principles revealed by our research, however, will be equally applicable to the design of tasks and questions included in other forms of unsupervised individual learning.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.