Guided Cognition Effects in Learning Literature

Abstract

This chapter reports 11 experiments that were done to determine whether Guided Cognition-designed homework would facilitate learning in high school and middle school literature classes. The experiments were done in an authentic learning environment, which means that students were in their normal school environment and were not aware that their learning was being observed. Students never saw the researchers, and all materials were handled by their regular teachers. The experiments fit seamlessly into the regular curriculum and did not affect students' course grades. Typically, a student would experience Guided Cognition-designed homework only once or twice during the entire school year. Guided Cognition homework was found to improve students' performance on unexpected quizzes by about 10%, approximately one letter grade. The effects were replicated with various literature (Shakespeare's MacBeth, Conrad's The Secret Sharer, Anouilh's Becket, Hinton's The Outsiders), under controlled time conditions, with and without explicit teaching of the content, with repetition of Guided Cognition homework, for grades 7–12 (ages 12–18) and for students of average, and advanced abilities. These results demonstrate that the advantages of Guided Cognition study are not due to specific content, time-on-task, teaching effects, or novelty and are obtained across a range of ages, ability levels, and subject matter. Improved learning resulted from engaging in effective cognitive processes triggered by the cognitive events that were embedded into the homework questions and tasks.

Keywords

Experiments 1 and 2: Can Guided Cognition-Designed Homework Facilitate Learning for Average- and Advanced-Ability Literature Students?

Method

Participants

Materials

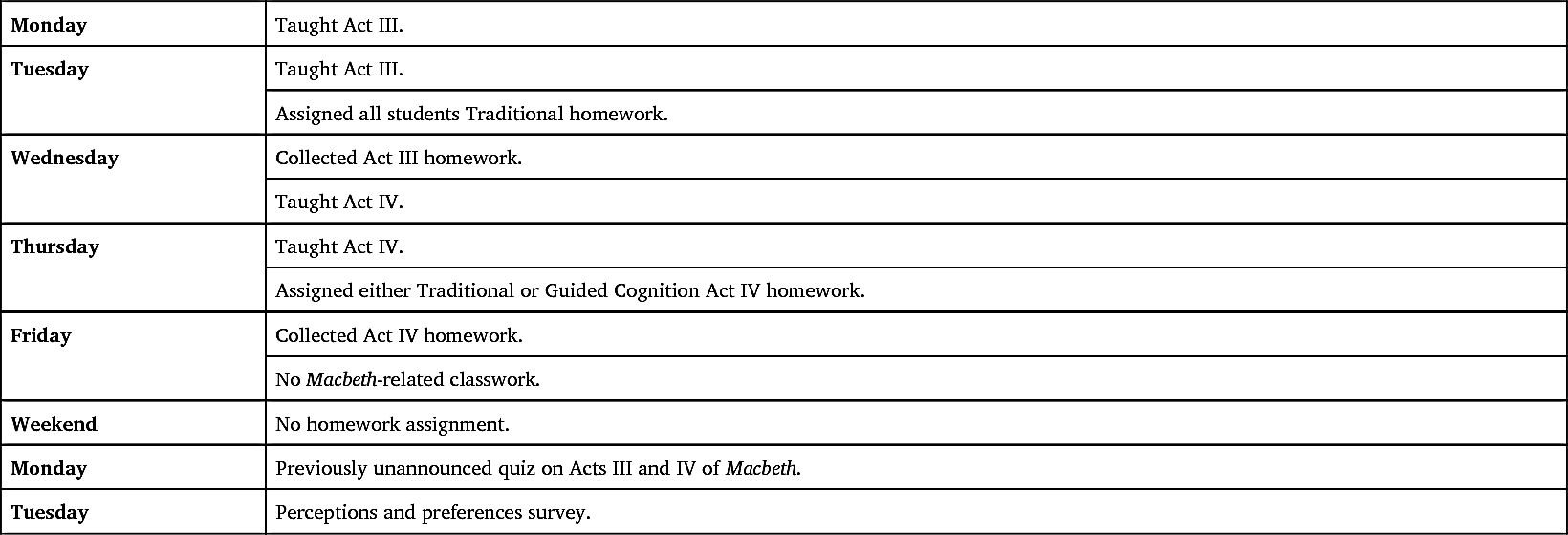

Design and procedure

| Monday | Taught Act III. |

|---|---|

| Tuesday | Taught Act III. |

| Assigned all students Traditional homework. | |

| Wednesday | Collected Act III homework. |

| Taught Act IV. | |

| Thursday | Taught Act IV. |

| Assigned either Traditional or Guided Cognition Act IV homework. | |

| Friday | Collected Act IV homework. |

| No Macbeth-related classwork. | |

| Weekend | No homework assignment. |

| Monday | Previously unannounced quiz on Acts III and IV of Macbeth. |

| Tuesday | Perceptions and preferences survey. |

Results

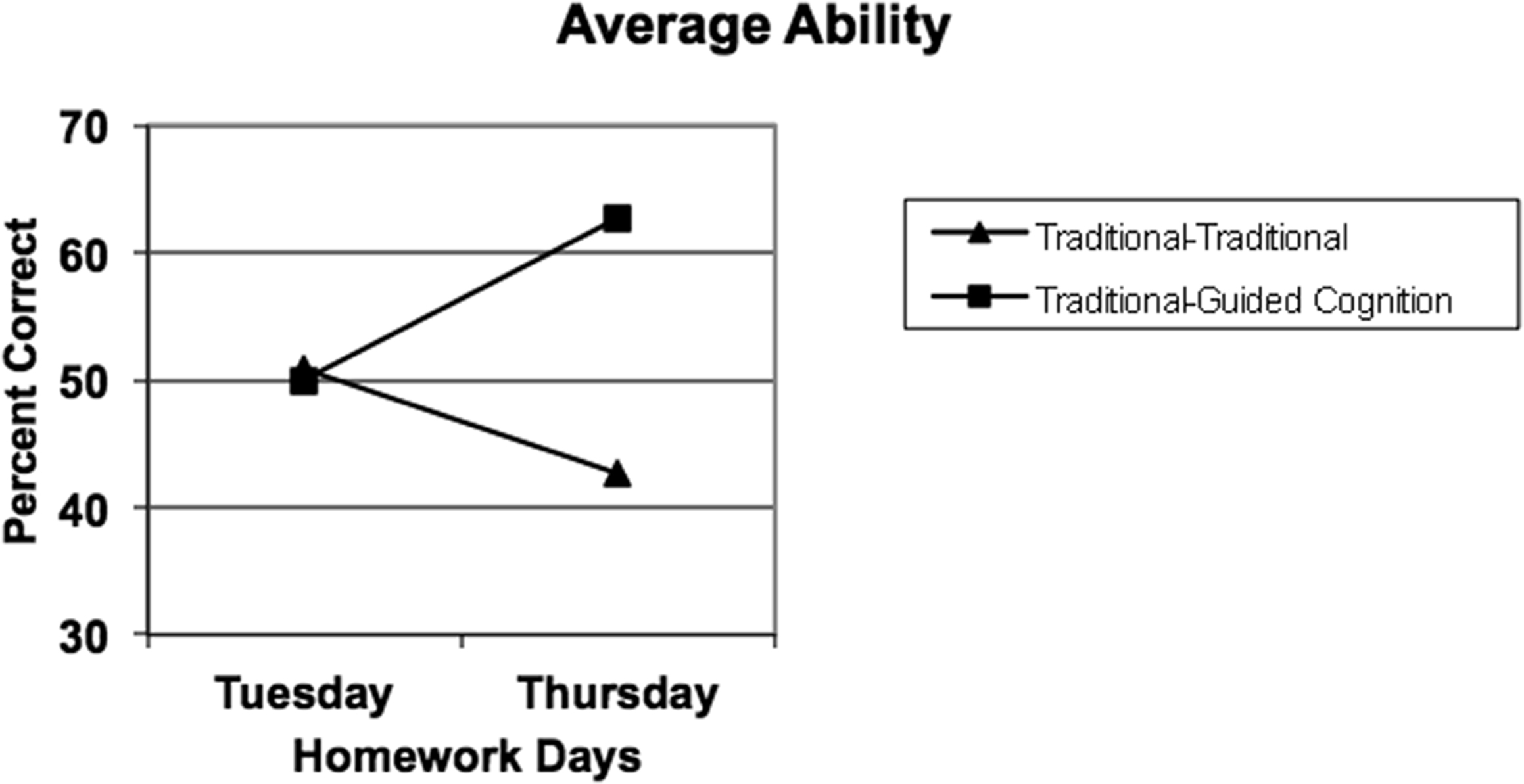

Performance data: Experiment 1 (average-ability students)

Performance data: Experiment 2 (advanced-ability students)

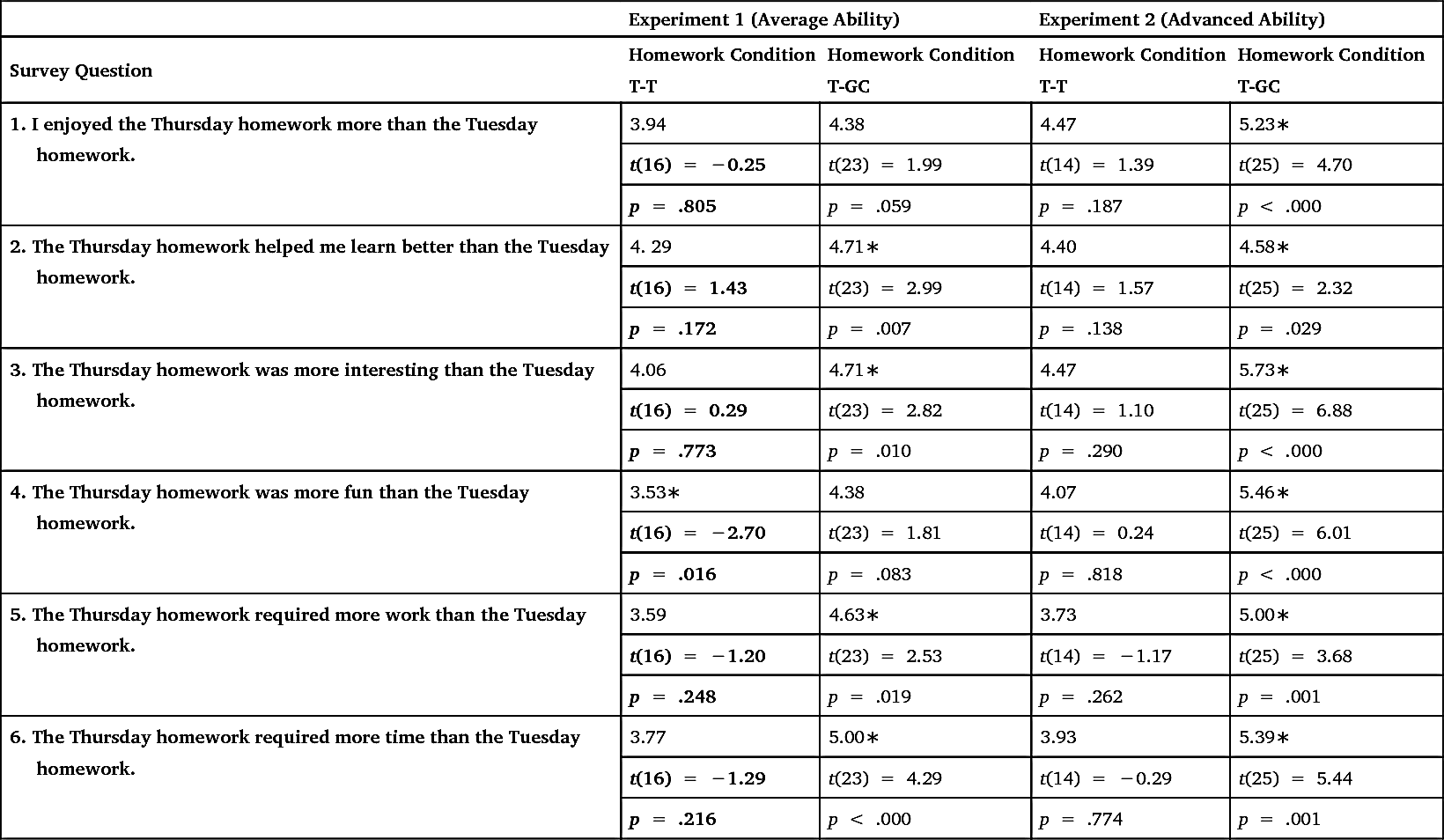

Perceptions and preferences survey data

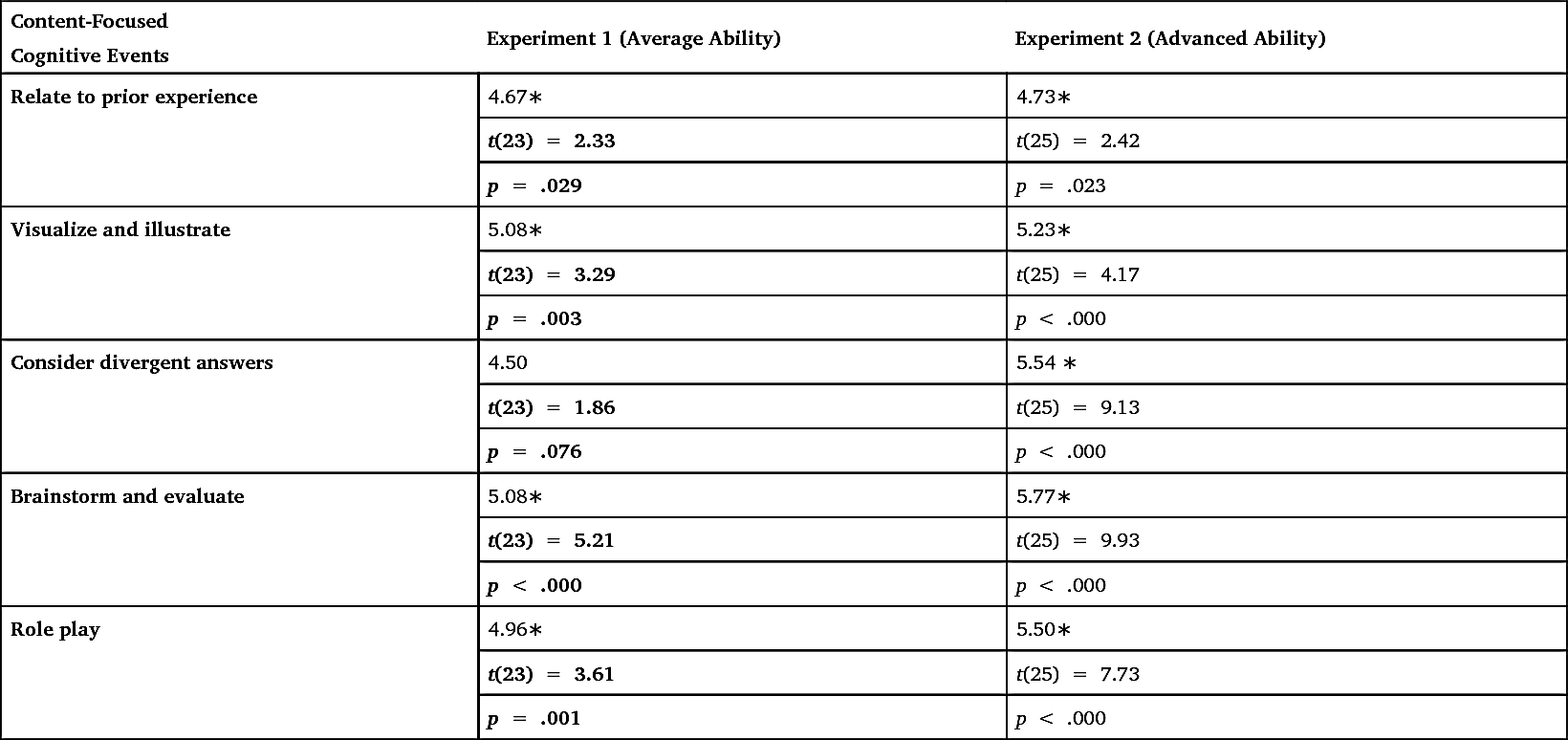

Table 3.1

Table 3.2

|

Process-Focused

Cognitive Events

|

Experiment 1 (Average Ability) | Experiment 2 (Advanced Ability) |

|---|---|---|

| Estimate and measure time | 3.21∗ | 2.50∗ |

| t(23) = −2.49 | t(25) = −6.16 | |

| p = .021 | p < .000 | |

| Set goals | 4.21 | 4.50 |

| t(23) = 0.62 | t(25) = 1.87 | |

| p = .540 | p = .073 | |

| Evaluate quality of work completed | 3.96 | 3.42 |

| t(23) = −0.14 | t(25) = −1.89 | |

| p = .890 | p = .070 | |

| Seek validation | 4.08 | 4.73∗ |

| t(23) = 0.24 | t(25) = 2.71 | |

| p = .811 | p = .012 | |

| Evaluate quantity of work completed | 4.50 | 4.27 |

| t(23) = 1.73 | t(25) = 0.83 | |

| p = .097 | p = .417 |

Experiments 3 and 4: Is Guided Cognition Effective When We Control Homework Study Time and When We Eliminate Teaching?

Method

Participants

Materials

Design and procedure

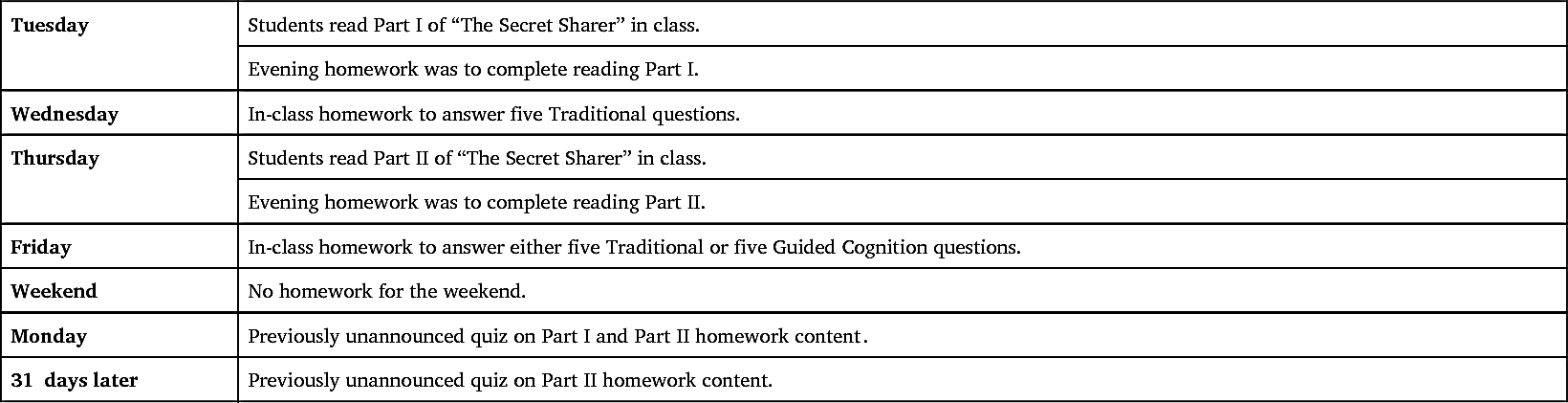

| Tuesday | Students read Part I of “The Secret Sharer” in class. |

|---|---|

| Evening homework was to complete reading Part I. | |

| Wednesday | In-class homework to answer five Traditional questions. |

| Thursday | Students read Part II of “The Secret Sharer” in class. |

| Evening homework was to complete reading Part II. | |

| Friday | In-class homework to answer either five Traditional or five Guided Cognition questions. |

| Weekend | No homework for the weekend. |

| Monday | Previously unannounced quiz on Part I and Part II homework content. |

| 31 days later | Previously unannounced quiz on Part II homework content. |

Results

Discussion

Experiment 5: Can Learning Be Predicted by Time Spent on Either Traditional or Guided Cognition Homework?

Method

Participants

Materials

Design and procedure

| Monday | Becket was introduced by the teacher. |

|---|---|

| Evening homework was to read Act 1. | |

| Tuesday | Discussion of Act 1. |

| Students began reading Act 2. | |

| Wednesday | Discussion of Act 2. |

| Evening homework was to complete reading Act 2 and to answer either five Traditional or five Guided Cognition questions about Acts 1 and 2 while keeping track of the time spent doing so. | |

| Thursday | Homework was collected. |

| Classwork unrelated to the play. | |

| Friday | Classwork unrelated to the play. |

| Break | Ten-day semester break without homework about Becket. |

| Second day after break | Previously unannounced review activity (quiz) on Acts 1 and 2 of Becket. |

Results

Content retention

Time on homework

Relation of time spent on homework and subsequent performance

Experiments 6 and 7: Do the Benefits of Guided Cognition Persist, or Are They the Result of Novelty?

Method

Participants

Materials

Design and procedure

| Monday | Taught Act III. |

|---|---|

| Tuesday | Taught Act III. |

| Assigned Traditional or Guided Cognition homework for Tuesday evening. | |

| Wednesday | Collected Act III homework. |

| Taught Act IV. | |

| Thursday | Taught Act IV. |

| Assigned Traditional or Guided Cognition homework for Thursday evening. | |

| Friday | Collected Act IV homework. |

| Classwork was unrelated to Macbeth. | |

| Weekend | No Macbeth-related homework. |

| Monday | Previously unannounced quiz about Acts III and IV. |

Results

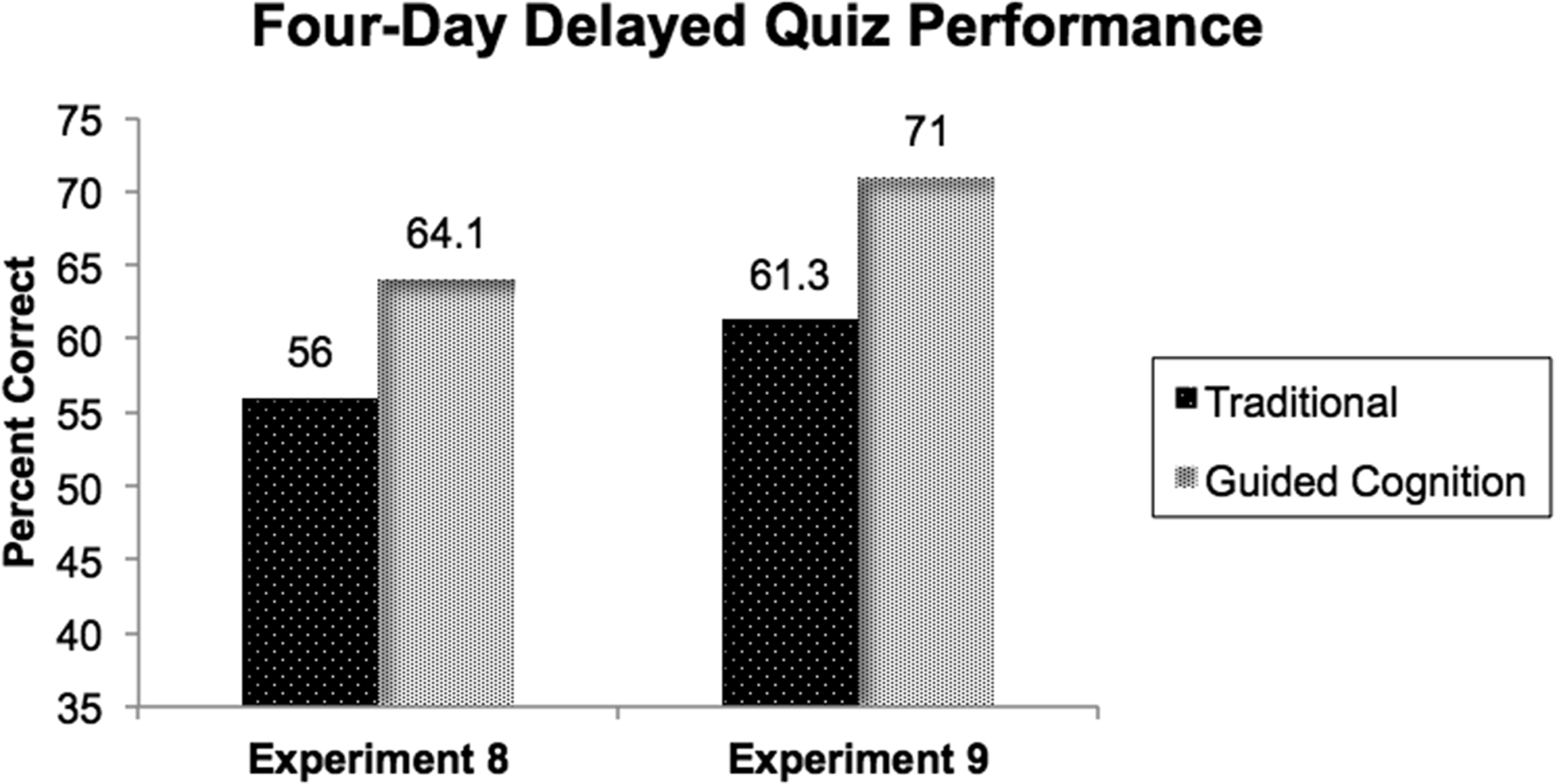

Experiments 8 and 9: Is Guided Cognition of Unsupervised Learning Effective for Younger Students?

Method

Participants

Materials

Design and procedure

| Wednesday | Students were assigned homework to read Chapters 4–6 of The Outsiders. |

|---|---|

| Thursday | In-class homework to answer five Traditional or five Guided Cognition questions. |

| Friday | Unrelated classwork. |

| Weekend | Unrelated homework. |

| Monday | Previously unannounced quiz on content of Thursday's in-class homework. |

Results

Discussion

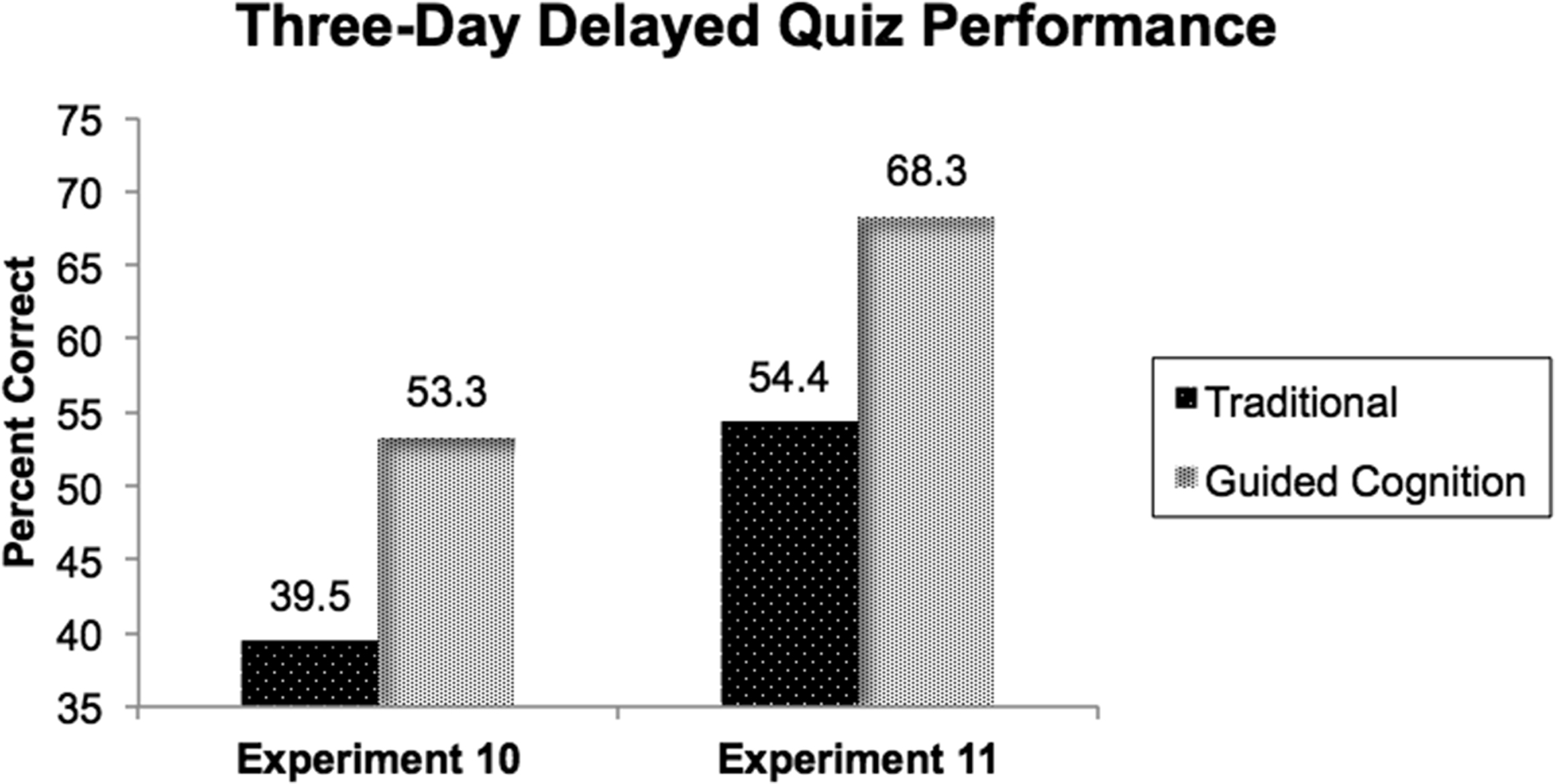

Experiments 10 and 11: Do Process-Focused Metacognitive/Planning/Evaluative Cognitive Events Promote Learning as Do Content-Focused Cognitive Events? Which Individual Cognitive Events Are Effective for Learning During Homework? Does Immediate Experience with Guided Cognition Tasks Affect Subsequent Unguided Learning?

Method

Participants

Materials

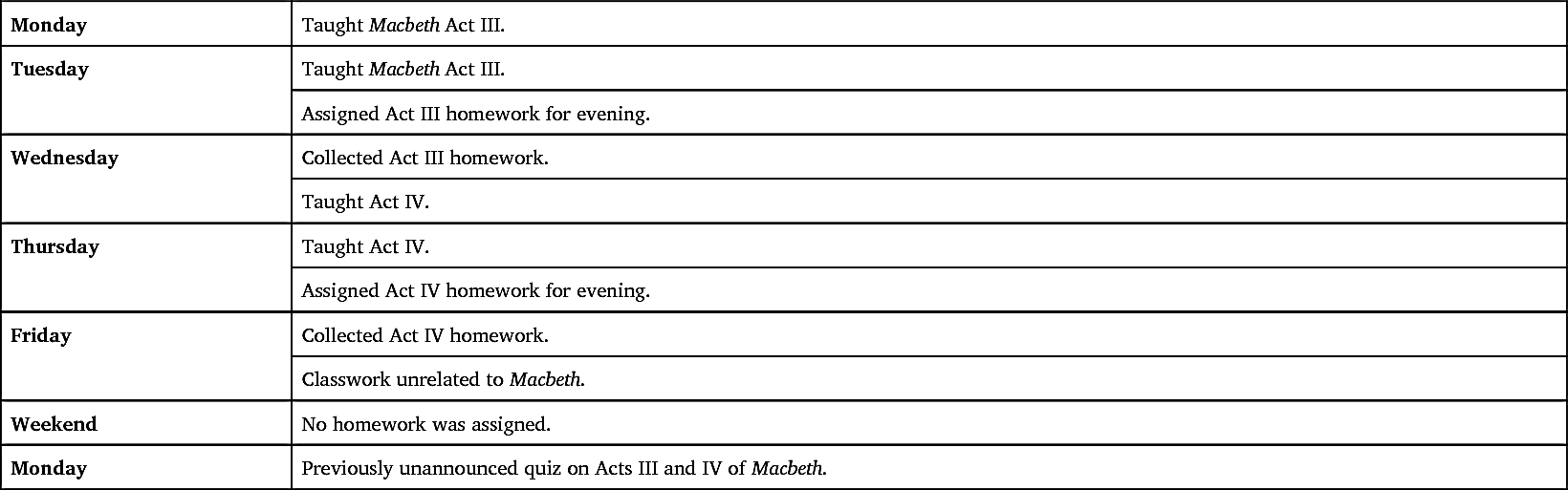

Design and procedure

| Monday | Taught Macbeth Act III. |

|---|---|

| Tuesday | Taught Macbeth Act III. |

| Assigned Act III homework for evening. | |

| Wednesday | Collected Act III homework. |

| Taught Act IV. | |

| Thursday | Taught Act IV. |

| Assigned Act IV homework for evening. | |

| Friday | Collected Act IV homework. |

| Classwork unrelated to Macbeth. | |

| Weekend | No homework was assigned. |

| Monday | Previously unannounced quiz on Acts III and IV of Macbeth. |

Results

Overall effects of Act III homework

Effects of individual content-focused cognitive events in Act III homework

Table 3.3

Table 3.4

Proactive effects of Guided Cognition experience

Discussion

Conclusions of Guided Cognition Research for Literature Homework Design

- 1. Guiding cognition through the wording of homework questions and tasks can engage students in specific cognitive events that elicit learning-effective cognitive processes, which significantly increase learning from homework.

- 2. Homework effectiveness is not a simple function of time spent on the tasks but is a function of the kinds of cognitive events (and their corresponding cognitive processes) that students engage in while studying.

- 3. Gains from Guided Cognition homework are found with and without explicit teaching, so the homework itself is a valuable part of the total learning effort.

- 4. Benefits from Guided Cognition homework are not due to novelty. This result implies that Guided Cognition can be used frequently without loss of effectiveness.

- 5. Guided Cognition benefits may become more apparent at longer retention intervals, so this form of homework may be of great benefit for very long-term retention.

- 6. Students generally perceive content-focused cognitive events as helpful for learning, but they generally perceive metacognitive/planning/evaluative process-focused cognitive events as not helpful for learning.

- 7. Content-focused cognitive events are effective for learning specific content, but metacognitive/planning/evaluative, process-focused cognitive events, under the conditions of our experiments, are not.

- 8. Each of the five content-focused cognitive events that were used in our experiments (relate to prior experience, visualize and illustrate, consider divergent answers, brainstorm and evaluate, and role play) was effective in improving learning when inserted into homework questions.

- 9. Immediate experience with Guided Cognition homework may have a proactive benefit for average-ability students on subsequent unguided study.

- 10. The benefit of Guided Cognition varies from content to content, but overall it can be expected to increase subsequent quiz performance approximately one grade or more, assuming that grades are 10 percentage points apart.

- 11. Average-ability students who receive Guided Cognition homework approach, and in some cases match, the performance of advanced-ability students who receive Traditional homework.

- 12 The Guided Cognition effect in studying literature has been replicated with a variety of content (Shakespearean tragedy, modern drama, classic novella, young adult novel); over a wide range of grades (7–12) and ages (12–18); and for average- and advanced-ability students.