07 Release/Return

RELEASE/RETURN

Throughout this book, I’ve really tried to focus on the positive aspects of HR and people management. This is partly to dispel the myth that HR is only about negative or unpleasant activities, but also to show the genuine force for good that HR can be for your business. However, there comes a time when what might be perceived to be more negative issues have to be faced head on.

And that is an important point to make. If there are problems of some sort with individuals or the business, there is rarely a positive outcome from ignoring them and hoping they’ll go away of their own accord. Of course, there are always exceptions, but typically problems fester and just get worse.

I’m sure you’ve experienced the able but largely anti-social intermediate designer who is hard to staff on projects because people just don’t want to work with them. Often, because the problem is not specifically related to performance, and is quite personal and difficult to articulate, it will be ignored and the person may be passed around from project to project until there’s nowhere else for them to go. That’s when the frustration with the situation boils over and HR gets a call saying ‘they just have to go!’. If HR had been involved sooner and the problem raised earlier, there may have been a less drastic solution.

So, the topics addressed in this chapter are:

- > Addressing problems and performance management, including sickness absence management

- > Disciplinary and grievance issues

- > Release: in terms of dismissal, redundancy and resignation

- > Return.

Before I go any further, I should mention that the title of this chapter is a misnomer, because release may not be the ultimate conclusion of some of the procedures we’re going to talk about; but it might be and that’s something that those involved need to be aware of from early on. But let’s not focus on this as an unstoppable train, there are always stages along the way at which processes can be stopped and directions changed.

1. Addressing Problems and Performance Management

It would be vain to think that I could list all the problems that you might ever have and offer solutions for them. Rather, the intention here is to give examples of some of the most common problems, and also to put tools at your disposal that you can use as might seem appropriate in the particular circumstance.

Common Problems That Appear Difficult to Address

Long-Term or Regular Sickness Absence

There seems to be a fear that you cannot address sickness as an issue. You can. However, it can be relatively complex depending on the specific circumstances. Simple guidance would be:

- > Be conscious of your responsibilities under the Equality Act and potential disability discrimination.

- > Be sure to seek input from the staff member.

- > Seek professional input – ask for a GP report or fund an occupational health (OH) assessment. You cannot rely on your own research or the staff member’s interpretation of what their GP has said.

- > Consider reasonable adjustments or temporary changes to the employee’s role, tasks or methods of working, even if their condition is not a formal disability.

- > If in any doubt, seek the advice of an employment lawyer.

Ultimately, if someone is unable to carry out their job because of illness, it is not impossible to dismiss them from employment, but you must be sure to consider all other options first.

Poor Attitude

This can be difficult to address because it is tricky to articulate or pin down. The secret is to stick to the business impact and the impression or perception of the person’s behaviour or actions. For example, saying: ‘When you are being briefed on your role on this project, you do not seem to be giving your full attention and so seem uninterested. This gives a very negative impression to the person briefing you and the rest of the team.’

Conflict between Two Individuals

It may seem like a good idea to get them both in the same room to ‘thrash it out’, and it might work, but there is a greater chance that it will just exacerbate the situation, or there will only be a superficial fix reached. Try a more subtle approach such as mediation if you want a long-lasting outcome. Don’t expect people to become bosom buddies, your goal is that they work well together, anything else is a bonus.

How Performance Management Helps to Solve Problems

In Chapter 5 we discussed the ongoing nature of performance management and how an appraisal process fits into that concept. Obviously, not all performance will be good, and so now is the time discuss how to manage poor performance when it arises.

Imagine the situation where you’ve had an appraisal with someone and highlighted areas where you feel that their performance needed to improve, and after a couple of months there is no improvement. What do you do?

Each situation will have its individual circumstances, but there are some basic principles which you need to follow:

- > Make sure the staff member is aware of what is expected of them. This could be by highlighting the relevant part of their job description, it could also be written down on their appraisal form, or it could be in written confirmation of an informal chat where you’ve raised any issues of concern. This could be as simple as an email.

- > Ensure that adequate resources are available for them to do their job. Make sure they have been given enough time to meet deadlines, they have the appropriate tools (software, for example), and they have the appropriate information and team input.

- > Check in with them. This might just be an informal ‘how’re you getting along?’ but the aim is to head off any further problems before they get worse.

- > Set a deadline or timeframe to have a more structured catch up meeting – this could be two weeks/ four weeks/two months. There is no definitive correct timeframe. It will depend on what the issue is. There is little point in having a catch up meeting with someone when they haven’t had the chance to show that they have understood the problem and been able to improve upon it. It may be a simple question of opportunity arising.

- > Be sure that you can honestly say that you’ve done all you can to help them achieve the appropriate level of performance.

Only once you’ve ticked these boxes, should you be considering more formal action.

You may hear people refer to putting someone on a performance management plan or similar. What this entails, in reality, is following the steps above. They will have sat down with their employee, explained what is expected of them, made sure they understand what’s expected of them and set a realistic timeframe for the expectations to be met. (This is another occasion where those SMART goals referenced in Chapter 5 come in useful.)

If, after all these steps have been followed, there is still no perceived or sufficient improvement, you might then decide to make use of the formal disciplinary procedure (see below).

How to Address Misconduct and Gross Misconduct

Misconduct relates to some form of action and behaviour that is not acceptable in the workplace. More often than not you will have lists of examples in your disciplinary policy. There is no standard list of misconduct or gross misconduct, although you will find very similar examples in most companies. It’s also possible to tell what issues a particular company has struggled with by what is listed in their examples.

It is highly unlikely that you will be able to list every possible misdemeanour that may arise within your company, so such lists should always be examples and not exhaustive.

Most issues are fairly obvious, as is the difference between misconduct and gross misconduct. As it suggests, gross misconduct is reserved for serious issues such as racism or theft or violence, but may also include matters that are serious to the specific company. For example, poor timekeeping may typically be considered to be misconduct, but in a company where keeping to a schedule is a key part of the service, such as Transport for London or an airline, poor timekeeping may be listed as gross misconduct.

As with performance related issues, there is a general expectation that minor instances of misconduct would be addressed informally in the first instance.

Often, people don’t seem to understand how others may view their actions or behaviour until it’s pointed out to them. More cynically, it’s possible that some people may have been pushing their luck, and when they realise that they haven’t slipped under the radar, they will simply stop the inappropriate behaviour. It’s equally true that you may have several informal chats with some people and they will still not realise the implications of their behaviour. In such instances, you may find that invoking the disciplinary procedure is necessary simply to get people to understand that you take these actions seriously.

2. The Disciplinary Process

How and When to Use the Disciplinary Process

The phrase ‘putting someone on a disciplinary’, which you often hear being bandied around, is rather meaningless. Not to get too pedantic about it, you should not begin a formal disciplinary procedure until the time is right and you’ve pursued other possible avenues to address the problem.

It’s worth remembering why the disciplinary process exists: it is a means whereby an employer can address instances of poor performance or misconduct in a structured manner. It isn’t a cane to thrash recalcitrant employees with indiscriminately. It should always be used appropriately and in context.

The Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service (ACAS) produces guidelines regarding both the disciplinary and grievance procedures. Although the ACAS guidelines are not legally binding, if you fail to follow the guidelines, you may still fall foul of an employment tribunal judge in their ruling. The guidelines are there for the purpose of providing fairness and consistency in the way that employees are treated.

Before you embark on the disciplinary process, remember the purpose!

The process may seem very formal and unfriendly, and it can be easy to get lost in the process. Never forget your original purpose: you are looking for certain behaviour or actions to change. Throughout the whole process, remain approachable and keep the lines of communication open. Just because you’ve started the process, doesn’t mean that the end is inevitable. Be open to apologies or some level of contrition. Use the process rather than allowing it to become the driving force.

There are four basic stages of the disciplinary process: investigation; formal meeting; documented outcome; and appeal.

Investigation

You should never make any assumptions about a potential disciplinary matter until a thorough and objective investigation has taken place. The ACAS guidelines suggest that an independent party conducts the investigation if possible, which is why some smaller companies may choose to use an external consultant.

An investigation may take the form of interviewing witnesses to an incident and taking statements, or reviewing and printing off emails and other correspondence. Basically, this is the process of gathering evidence to help decide whether or not the matter should be taken further. If it is decided that there is a disciplinary issue to answer, then the employee should be provided with all the related evidence that you have used to make the decision.

Formal Meeting

A formal meeting requires an invitation and reasonable notice, as well as notification of the right to be accompanied.

![]() Invitation to disciplinary meeting letter

Invitation to disciplinary meeting letter

There is no specific legal requirement about the amount of notice that should be given, but a common guideline is that a minimum of 48 hours is reasonable. The point is to give the employee reasonable time in which to prepare. Obviously, if they have lots of documentation to read through and prepare a response to, this may take longer.

Each case will be judged on its own merits. The invitation itself should clearly state the reasons for the meeting, and not just something vague such as ‘insubordination’. Be specific (e.g. ‘you spoke loudly using inappropriate language to your manager which constitutes insubordination’).

The meeting itself should enable the employee to give their side of the story. But you also need to be sure to manage the meeting and ensure that the main reason for the meeting is raised and discussed. We discuss certain difficult situations that may arise below.

You would not usually inform the employee of the outcome of the meeting immediately in the meeting itself. A period of reflection is advisable, even if it’s only fifteen minutes or so. Be sure of your facts and reflect upon any business impact as the main driver behind your decision.

Documented Outcome

It may be that, after the meeting, you agree with the employee’s version of events and choose not to take the matter any further. You still need to confirm this in writing. If this means that another employee becomes involved in an investigation or disciplinary meeting, the first employee need not know that, or certainly need not know the details. Alternatively, you may decide that a sanction of some sort is warranted. Again, this needs to be confirmed in writing.

![]() Outcome of disciplinary meeting letter

Outcome of disciplinary meeting letter

Appeal

Your employee will have the right to appeal against any sanction that you might choose to impose. Whoever conducts the appeal meeting should be different from and of equivalent status to the person taking the original disciplinary meeting. Often with small companies that can be difficult, so there is some leeway given depending on who may be available: another benefit of using external consultants, who also provide an additional level of objectivity to the situation.

The appeal process concludes the internal disciplinary procedure. Any further recourse by an employee would be external, for example via an employment tribunal.

![]() Invitation to appeal meeting letter

Invitation to appeal meeting letter

![]() Outcome of appeal meeting letter

Outcome of appeal meeting letter

3. The Other Side of the Coin: The Grievance Process

Just as with the formal disciplinary procedure, the formal grievance procedure is for use if informal or other means have not been successful in resolving an issue. And as with the disciplinary procedure, the best recommendation is to use the ACAS guidelines.

Grievances can be regarded as the other side of the coin to ‘disciplinaries’. The grievance procedure is a way in which an employee or worker can raise issues about which they feel aggrieved. Most often, if an employee has an issue of some sort, they will have a chat with someone or send an email about it, and the manager or HR representative will help to resolve it. In some cases, however, an employee may feel that the matter has not been resolved to their satisfaction and they may choose to raise a formal grievance. If this is the case, you do need to take it seriously.

Grievances are typically related to working conditions (e.g. working hours, or pay) or working relationships with colleagues or others.

However, the grievance process is not intended to be a way that confrontational employees can get their own way or refuse to be appropriately managed. A manager does have the right to manage!

Who Should Conduct the Grievance Process?

Every company has to have in its written statements of terms and conditions the name or the title of the person that the staff can go to with any grievances. Consider carefully who this might be.

In smaller companies, you may have little choice because it will be expected to be a senior person. However, if a grievance is against a line manager or senior person, then obviously it would be inappropriate for them to conduct the process. It’s also a good idea for the person conducting the process to be, shall we say, of a calm and unflustered nature. Unfortunately, grievances by their very nature can become quite personal or vitriolic towards the company. Listening to what is said calmly and objectively is part of the process.

To the person raising the grievance, it is often the case that the mere act of having the opportunity to give their views and say their piece out loud will go a long way to helping to resolve the situation. This is especially true if the complaint is about not being taken seriously or not being listened to.

As with disciplinary issues, sometimes it is good sense simply to be seen to be as objective as possible and engage external consultants in the grievance process – whether for the investigation alone, or also for any formal meetings. Certainly, smaller organisations may find themselves seeking external support for any appeals that may arise. As with the disciplinary process, there are the four basic stages of the grievance process:

- > Investigation: You need to know what the grievance is about. It is strongly suggested that part of the investigation process would be to meet with the person raising the grievance. You may also wish to offer them the right to be accompanied to the investigation meeting, even though it is not a formal meeting. This might seem an obvious point, but sometimes companies will conduct an investigation into the matters raised by an employee, then call the employee into a formal meeting in an effort to resolve the matter, and only then find out that there are additional issues about which they were unaware. Simply, make sure that the investigation is thorough and maintains a balance between confidentiality and ensuring that all sides of the story are reviewed.

- > Formal meeting: Even if you feel that the grievance is unfounded after investigation, you should still hold a formal meeting with the team member who raised the grievance. This formal meeting is an intrinsic part of the ACAS guidelines. To fail to hold it would suggest you have not taken the matter sufficiently seriously. Just as with the disciplinary process (described above), you should issue a formal invitation with at least 48 hours’ notice, including any documentary evidence you are going to use to reach a decision, and offering the employee the right to bring a companion to the meeting. It is very important that the employee has every opportunity during the meeting to raise all their complaints <

- and that this opportunity is noted. This ensures that you are seen to have addressed all the issues.

![]() Invitation to grievance meeting letter

Invitation to grievance meeting letter

- > Documented outcome: You should consider all that has been put before you and then decide if the grievance is upheld or not (i.e. whether you agree with the person raising the grievance or not). This decision should be recorded in a letter to the employee.

![]() Outcome of grievance meeting letter

Outcome of grievance meeting letter

- > Appeal: The team member has the right to appeal against the decision reached. This will be within a certain number of days (use the ACAS guidelines if you have no policy of your own) and to someone who was not involved in the original investigation and meeting. External consultants can support you if you have run out of senior staff members to conduct the appeal and hold the meeting. The appeal does need to set out specific grounds for disagreeing with the decision made. Once the appeal meeting has been held and a written response provided to the employee (e.g. based on the letter used for a disciplinary appeal), that concludes the internal process.

Frequently Asked Questions about Disciplinary and Grievance Procedures

Q. What happens if someone makes a complaint, but won’t raise a formal grievance and doesn’t want their name mentioned?

A. Explain that this will hinder your ability to make a thorough investigation and try to find out why they don’t wish to be involved by name. It may be that they feel bullied or harassed so this is a form of selfpreservation, or it may be that they have some kind of grudge and are merely making trouble. Ultimately, if someone does not wish to be named, you cannot force them, but in some respects this will make their evidence less strong.

Q. What happens if you invite someone to a disciplinary meeting and they then raise a grievance against you?

A. The act of inviting someone to a disciplinary meeting is not in itself sufficient reason to raise a legitimate grievance. However, if the grievance has some other wider basis it will need to be addressed by someone other than you. If the disciplinary matter and grievance subject are connected, the two processes may be able to proceed in parallel. However, if the grievance matter is separate, the disciplinary process should be put on hold pending the outcome of the grievance.

Q. What happens if you invite someone to a disciplinary meeting and then they are signed off with stress for a month?

A. This can sometimes be used as a delaying tactic, but equally can be a valid and genuine problem. Allow them time to recover fully, ensuring that their absence is fully covered by a Statement of Fitness for Work or ‘fit note’. Don’t badger them while they are off work. When they return to work, with the appropriate note indicating their fitness to do so, you can recommence the process.

Q. What happens if someone raises a grievance, it is found to have no grounds, but they still refuse to work with the person about whom they raised the grievance?

A. Be sure that the grievance procedure was followed properly, including a thorough and objective investigation. Try mediation. Discuss the situation with them and perhaps consider changes to their working pattern or conditions if possible. But ultimately you may be in a position where using the disciplinary procedure is an option. Refusing a reasonable management instruction can be deemed to be insubordination.

In certain serious instances, a possible outcome of a disciplinary or grievance procedure might be dismissal.

4. Departing Employees

This part of the chapter focuses on that often challenging time when one or a number of people leave your company. Remember that this is another one of those occasions when your actions will be under the microscope and subject to the rumour mill.

Whether the departure is your choice or their choice, whether you are dancing with glee that a particularly tricky employee has decided to resign or whether you have agonised over making a valued employee redundant, you will be judged. And this judgement will affect your brand as an employer.

There are three principal ways in which staff may leave your company: dismissal, redundancy; and resignation.

You’ll notice that the first two will be your decision, whereas the third is the decision of the staff member.

In each case, do not forget to follow the proper process. Let’s take each instance in turn.

Dismissal

The implication here is that some kind of misconduct or poor performance has taken place and you’ve gone through the process of addressing it informally, but it has been repeated or another instance has arisen or the performance hasn’t improved.

So, you have done all you can to rectify the situation. You’ve given your staff member clear guidance, adequate resources and the opportunity to improve or change. You’ve implemented the formal disciplinary procedure and have worked your way through the various sanctions, or have found that the single instance of misdemeanour is so serious that you have made the decision to dismiss your employee.

You do need to be absolutely sure this is the right option. It is a huge responsibility to deprive someone of their livelihood.

If you dismiss an employee, having gone through the appropriate process, you will of course confirm this in writing, and should give the reason for the dismissal.

Legitimate Reasons for Dismissal

In order for dismissal to be fair, it must be for one of five specific reasons:

- > Capability – you’ve gone through the performance management process and your employee is still unable to fulfil their duties to an appropriate standard; or perhaps one of your staff has a long-term illness, you’ve done all you can to support them and give them a chance to recover, but they remain unable to work.

- > Conduct – you’ve gone through the disciplinary procedure and found your employee is guilty of repeated misconduct or maybe one instance of gross misconduct.

- > Illegality or contravention of a statutory duty – for instance, a driver loses their licence.

- > Some other substantial reason e.g. an employee is sent to prison - this is something of a catch-all, but still requires a proper dismissal process to have been followed

- > Redundancy – this is discussed separately below.

Redundancy

I’m sure it will come as no surprise that ACAS has guidelines for redundancy which you should follow.

Redundancy must be for legitimate reasons, namely: the closure of a business or workplace, or changes in the workplace that mean that fewer employees are needed. Many of us experienced redundancy during the recent economic crisis. Indeed, the architecture profession has probably had more significant experience of this process than most.

It seems commonly viewed that the redundancy process itself is too long and drawn out, and has negative effects on all those involved. (You may hear: ‘People don’t like to be kept hanging around’; ‘It has such a negative effect on morale that no work gets done while the consultation period is going on.’) For that reason, some companies try to cut it short, risking claims from disgruntled employees. However good the intentions, if you don’t follow the process – including having a meaningful consultation period – then you (the company) are automatically in the wrong.

The challenge during redundancy, as with the disciplinary process, is to balance getting the process right with retaining your sensitivity.

Ironically, given the prevalence of redundancy in the past few years, people are more used to the process and understand that it isn’t just some sadistic series of events dreamt up by the HR department to keep themselves in a job. There is a logic to the process, in that companies should not be able to simply implement cuts in staff numbers without input from those who may be affected. There should be the opportunity for people to offer to work fewer hours, or take a pay cut for a period of time. These options have certainly worked to stave off compulsory redundancies in some cases over the past few years.

The key points of the redundancy procedure are:

- > Planning: Basically, how to avoid compulsory redundancies (e.g. perhaps by implementing reduced hours or salary cuts).

- > Identifying the pool for selection: This will be those doing similar work or in a particular department where there is over-capacity or where finances cannot support the existing numbers; a poorly planned pool will automatically make the whole process unfair.

- > Seeking volunteers: It is good practice to offer a voluntary redundancy package, which may minimise compulsory redundancies.

- > Consulting employees: This is a legal requirement: the timing will vary depending on the number of likely redundancies; the consultation must be meaningful.

- > Selection for redundancy: This must be accomplished using objective criteria such as performance or skills.

- > Appeals Appeals and dismissals: A formal meeting and notice of dismissal, including the right to appeal the decision must be part of the process.

- > Suitable alternative employment: Continue to offer opportunities if they arise.

- > Redundancy Redundancy payment: Statutory amounts apply and you can choose to offer more if you wish and have the abilit>to do so.

- >> Counselling and support: Again, it’s good practice to do what you can, even if it’s as simple as helping with CVs or offering the contact details of recruitment agencies.

If you believe you may have to make redundancies, do involve your staff in the process. If you explain the challenges that you face, you may be surprised at the sacrifices that people are prepared to make to support the business. It’s another of those instances where, if you engage people and make them feel part of the decision-making process, they will usually act in the best way for the business.

Resignation

In this case, the choice is taken out of your hands. Sometimes, a resignation will be welcome; sometimes it’s bad news and you may ask the staff member to reconsider.

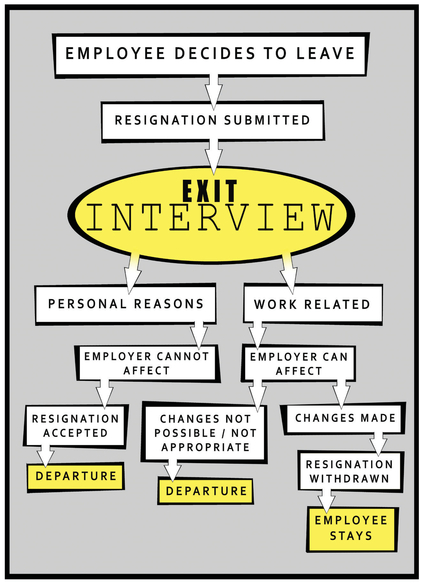

In any event, it is always good practice and a useful experience to hold exit interviews with the team member.

The reasons for leaving may be personal and something that you can do nothing about such as relocation, childcare or health. If that’s the case, you can still ask a departing employee some useful questions about their working experience in your company.

If the reasons are more career orientated or related to problems at work, you have the opportunity to do something about it.

5. Exit Interviews

Exit interviews should be carried out with all departing employees: you can always learn something. Conduct the interview in the office in a meeting room if possible (i.e. not just down the pub or over lunch). This indicates that it is an important process to you, not just a bit of a chat. You can always take the person to lunch or for a leaving drink in addition.

Be sure to ask the same questions of each person who leaves, so that you have comparable information.

You may feel justified in being annoyed or resentful because a valued employee is leaving – especially someone who you’ve spent time and money on developing and who you saw as a part of the future of your company. I’m aware of individuals receiving calls from senior management and their wives expressing anger and betrayal, and trying to engender a feeling of guilt for resigning. This does not leave a positive image and can damage a company’s reputation. The best thing to do is to put a brave face on it, wish them well and say that they would always be welcomed back if an opportunity existed.

And, it does happen. The grass is not always greener. And people’s circumstances change.

6. Return

Back in 1961 Charlie Drake had a surprise hit with a novelty song ‘My boomerang won’t come back’. I couldn’t help but think of it when I managed a Boomerang Programme which catered for people returning to the company having left and spent time elsewhere.

Despite the association of the song and, indeed, the ‘throwing weapon’ itself, the concept of celebrating someone’s welcome return to your company is a good one.

The ideal situation would be that they were a model employee who you were sad to lose, but who went away and gained all sorts of useful experience elsewhere at someone else’s expense, which they are now bringing back to the benefit of you and your company. It’s the scenario described above (and which worries you when you pay for people to go on expensive training courses).

However, in this new enlightened age where you treat your employees like adults and give them the freedom to learn and take control of their own professional development, this is the sort of thing that may happen. And, just as you may gain by it on one hand, you may lose by it on the other.

People vote with their feet and will move on to work at a company whose management style and business ethics match their own beliefs and values. This personal alignment with work is increasingly obvious within the workplace.

Summary: Departure and Return

Not all departures from your company are necessarily bad.

Don’t be bitter or vindictive when someone chooses to leave you. Aside from it being unprofessional and sometimes childish, it is more profitable to learn from the experience. See if there are any changes you can put in place to prevent the people you want to keep from leaving in the future.

If you are the one making the decision for the person to leave, be sure to follow the proper procedure so that you remain within the law, but also don’t forget that you are dealing with people and don’t lose your sensitivity to their situation. Even if they have committed a heinous act of gross misconduct, they have the right to understand the business impact of what they have done and that this is the driver behind your decision. Don’t make it personal or vitriolic or engage in pointless verbal or written slanging matches. Help them to learn from the experience so that they don’t do it again.