A City Brand Personality Model for international event marketing: An empirical research across multiple cultures

Cities, regions and countries compete globally for skilled workers, business investment and tourists. Place branding is the application of brand strategies and concepts to differentiate a city, region or country in order to create experiences that people desire based on the places where they live, work and visit. Due to the importance of the city brand in China, we examine how city brands are experienced in order to provide an insight into to how event managers can integrate city brand considerations into their marketing planning and strategies. Our research indicates that there are similarities in how people in North America, Europe and Asia personify cities. Additionally, we find evidence that these similarities can be measured by a shortened, easy-to-use version of Aaker’s brand personality scale. Based on this brand personality scale cities are able to measure the personality of a city. The results are interesting for stakeholders of a city, for example, because it helps them to understand the personality of their respective city.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Aaker

Aaker ![]()

![]()

![]()

1 Introduction

Cities, regions and countries compete globally for skilled workers, business investment and tourism. Places increasingly apply marketing theories and tactics as they compete and branding is a critical component of place marketing (Hankinson, 2007; Hanna and Rowley, 2011). Place branding is the application of brand strategies and concepts to differentiate a city, region or country in order to create experiences that people desire based on the places they live, work, and visit (Hanna and Rowley 2011; Hankinson 2007). This definition highlights the strategic management of the brand and the consumption experience of the brand.

The importance of the city brandings has been recognized in recent years, especially in China and has thus been examined from different perspectives (Go and Zhang 1997; Mercille 2005; Owen 2005; Xu 2006; Li and Kaplanidou 2008; Zhang and Zhao 2009; Meng and Li 2011). Reasons for this are high growth opportunities in tourism and the increasing attractiveness of a relevant representation of a city brand for investors and workers (Zhang 2009; Ding 2011).

Due to the importance of the city brand in China, we are going to examine how city brands are experienced in order to provide an insight as to how event managers can integrate city brand considerations into their marketing planning and strategies. Specifically, we will focus on the city brand personality component of city brands. First Principles were developed for this purpose in the 1970’s by Mayo (1973), Hunt (1975) and Crompton (1979). These days the city brand of a destination is one of the most frequently measured constructs in empirical research (Dolnicar and Grün 2012). Our goal is to identify the components of city brand personality that are generally recognizable across multiple cultures. In doing so, we hope to provide a city brand personality model that can be effectively applied to international marketing practices.

In general, brand personality is “the set of human characteristics associated with a brand,” (Aaker 1997, 347). Thus, the city brand personality construct represents the ways in which individuals personify their overall beliefs about a city. A city’s brand personality has been shown to be distinct from the city’s overall brand image (Ekinci and Hosany, 2006) and brand personality, in general, can have a positive distinct impact on customers’ trust and loyalty towards a brand (Siguaw et al. 1999). Research indicates that people associate human personality characteristics with cities, although the types of personality characteristics tend to vary across cultures (Ekinci and Hosany, 2006; Kaplan et al. 2010). We will now take a closer look at these existing unique city brand personality constructs, compare them with research on Aaker’s (1997) brand personality construct for products and propose a city brand personality model that can be more generalizable across cultures.

After we have proposed our model, we will provide the results of a study consisting of three samples, one from China, one from Germany, and one form the US, which suggest that our model can be applied across cultures for international marketing purposes.

2 A four-factor City Brand Personality Model

Aaker (1997) developed a five-factor brand personality model for products based on research administered in the US. These factors are sincerity, excitement, competence, sophistication and ruggedness. Sincerity consists of a product being perceived as down-to-earth, honest, wholesome and cheerful and is measured using 11 descriptive items. Excitement is also measured with 11 descriptors. The Excitement factor captures perceptions of a product being daring, spirited, imaginative and up-to-date. Competence consists of three facets, being reliable, intelligent, and successful. This factor is measured using 9 descriptive items. Sophistication is characterized by being perceived as upper class and charming and is measured by six items. Finally, ruggedness is measured by five items and is characterized by the facets of being outdoorsy and tough. Thus, this model has five factors, 14 facets, and 42 items that are used to measure the facets in each factor.

We have four goals with our proposed model. First, we want to identify a model that is generalizable and theory-based, so we will build on existing work rather than trying to define new factors, facets and measures. Thus, we will try to only utilize factors, facets, and measurement items that are part of Aaker’s (1997) five-factor model brand personality model. Secondly, we want to make sure that our model is consistent with the city brand personality construct. To do this, we will look for for consistencies between existing city brand personality models and Aaker’s (1997) model. In this way we are building on a body of city brand personality research. Thirdly, we want our model to be applicable in international marketing contexts, so we will research literature that extends Aaker’s (1997) model of brand personality to multiple cultures, even if it is not in a city branding context. The purpose of this is to identify if any brand personality factors, facets, and measures are consistent across cultures but may have not yet been considered in city branding contexts. Fourthly, we want to identify the most parsimonious measurement model possible so that it can be easily utilized by place and event marketers.

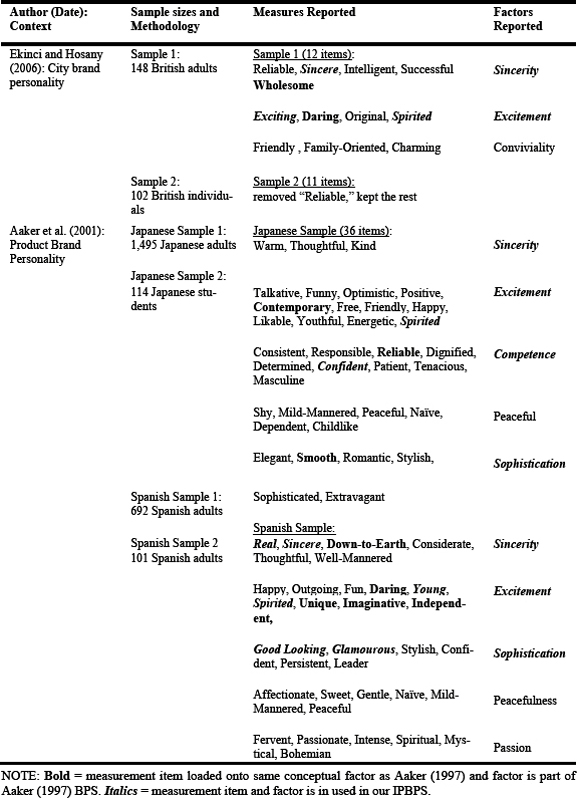

Table 1 summarizes the measures that were used by Ekinci and Hosany (2006) in a city brand personality context as part of a study of adults from Great Britain. Their research utilized a sample of 20 British participants to evaluate Aaker’s 42-items measuring brand personality to evaluate which ones were reasonable for use in city branding context. Their work led to 27 items being identified and the items were representative of each of the original five factors. As shown in table 1, an exploratory factor analysis identified only three city brand personality factors, not five. Moreover the only factors that were characteristic of any of the original five were the sincerity and excitement factors. It is interesting to note that some of the items their study uses to measure sincerity and excitement are items that were originally used to measure other factors in Aaker’s (1997) original model. Thus, for the purpose of building our model we keep the sincerity and excitement factors, but we only utilize the measurement items that were consistently grouped in each factor by Aaker (1997) and Ekinci and Hosany (2006). These are the first two factors in our proposed four-factor city brand personality model.

Next, we looked at the work of Aaker et al. (2001) who studied the brand personality construct in a product context but outside of the US and Great Britain. As shown in table 1, the factors of sincerity and excitement are again identified in both Spanish and Japanese samples. Also, at least one of the measurement items in each factor are the same as used for the respective construct in the city branding work done by Ekinci and Hosany (2006). Aaker et al. (2001) also identify the sophistication factor in both the Japanese and Spanish samples, although different measures were used for each factor. Additionally, some of the measurement items in these factors were items that were related to other factors in Aaker’s (1997) original work. Recalling that our goal is cross-cultural applicability, we include the sophistication factor in our model, but only utilize measures that were consistent with the original US-sample tested model (Aaker 1997).

Our research identified one other extension of Aaker’s (1997) brand personality construct to the context of city branding, the work by Kaplan et al. (2010) for several cities in Turkey. Kaplan et al. (2010) utilize a list of measures that go beyond the 42 items used by Aaker (1997), so we have not presented their work in the table. However, for the purposes of our research it is sufficient to note that excitement was identified, again, in a city branding context and competence also captures in this city branding context, along with ruggedness.

To summarize, sincerity, excitement and competence are all found in at least two brand personality studies completed in different countries, and each of these factors have been previously identified in at least one city brand personality context. Additionally, sophistication was recognized in brand personality studies in Japan, Spain, and the US, although these were all in product contexts. Moreover, for each of these four factors, at least two measurement items are consistent with those used in Aaker’s (1997) original conceptualization of brand personality.

Thus, we propose a four-factor city brand personality model for international marketing. The model consists of an excitement factor that is measured with five descriptors and captures perceptions of a city being spirited (three measurement items), exciting (one measurement item), and up-to-date (one measurement item). It also contains a sincerity factor that has three measurement items that represents the honest facet of this factor, a sophistication factor with three measurement times that represent the upper-class facet of this factor, and a competence factor that has three measurement items representing the successful facet of this factor. Each of these factors, facets, and measurement items are part of Aaker’s (1997) original brand personality construct, they have been at least partially identified in at least one other city brand personality context, and they have been at least partially identified in at least two other international contexts. Thus, the conceptual nature of the model is based on existing theory and empirical research.

3 Testing a four-factor City Brand Personality Model

In this study we will examine the extent to which our proposed 4-factor city brand personality model can be applied in international settings. Specifically, we will test the hypothesis of how our proposed 4-factor city brand personality model is applicable across cultures, thus being suitable for application in international marketing.

We will test this hypothesis using a confirmatory factor analysis of data collected from three samples. One sample consists of 217 Chinese college students attending a University in China, a second sample consists of 110 German college students attending a German University, and a third sample consists of 112 American college students attending a US University. In German and Chinese sample participants were instructed to read the provided list of descriptive words and use a 5-point scale to indicate the extent each word described the city where they attended school. The scale points ranged from “not at all descriptive” and “extremely descriptive”. In these samples, participants also had the option of indicating that they did not understand the meaning of a descriptor in relation to a city. In the US sample, students read the same set of descriptors and responded using the same scale to indicate how the extent to which each word described the city in which thy attended school. Students in the US sample were not given the option of indicating that they did not know the meaning of a word in relation to a city because we had reason to believe they were easily understood in the US, based on the reliability results presented in study 1.

Results. Table 2 shows the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) results for our study. Almost all factor scales exceed the minimal desired threshold for reliability, with composite reliability and coefficient alpha scores all over .600 (Bagozzi and Yi 1988). The only scale which does not have at least one of these measures of reliability meeting the threshold is the competence scale in the Chinese sample (composite reliability = .594; coefficient alpha = .518). Thus, overall, the scales appear to have sufficient measures of internal consistency across our three samples. Additionally, the AVE estimates are all above the strictest threshold of .500 in the US sample, and we find mixed results in the AVE estimates in the Chinese and German samples (Fornell and Larcker 1981). The AVE estimates therefore indicate that there tends to be more measurement error present in the Chinese and German samples than in the US sample. Overall, we believe that there is sufficient evidence in to suggest that these scales can be viewed as reliable for use in each of the three cultural settings we tested.

To asses our hypothesis that the four-factor city brand personality model can be used to understand city brand personalities in international marketing, we examine the fit indexes resulting from our CFA for each sample. Researchers suggest consulting multiple fit indexes to assess how well a hypothesized model performs in a CFA (Hatch 1994; Sivo et al. 2006). We considered four recommended indexes to test hour hypothesized model. The respective optimal cutoff points for concluding if a model is acceptable are .95 or higher for the CFI index, .88 or higher for the NFI index, .06 or lower for the RMSEA index, and a chi-square statistic that is less than two times the value of the model’s degrees of freedom (Hatcher 1994; Sivo et al. 2006). As shown in Table 3, three out of four fit indexes for the US sample and Chinese samples meet or exceed these optimal criteria. In the German sample, the respective indexes do not meet these optimal criteria. Thus, we conclude that our proposed four-factor model of city brand personality is acceptable in the US and China samples, but not in the German sample. However, a post-hoc analysis of the German sample reveals that a two-factor model consisting of the excitement factor and the sincerity factor is an acceptable model of city brand personality (CFI = .964; NFI = .889; RMSEA = .059; χ2 = 26 with 19 degrees of freedom).

4 Conclusions

Our research indicates that there are similarities in how people in North America, Europe and Asia personify cities. Additionally, we have found evidence that these similarities can be measured with a shortened, easy-to-use version of Aaker’s (1997) brand personality scale.

Our four-factor model of city brand personality clearly indicates that individuals in our China and US samples recognize excitement, sincerity, sophistication, and competence as identifiable personality traits of cities. Results from our German sample suggest that sophistication and competence may either be city brand personality traits that are less identifiable by people from European cultures or that they need to be understood differently than how our scales measure them. However, it appears that individuals in Germany, China, and the US are clearly able to associate excitement and sincerity as elements of a city’s brand personality.

Based on these results, marketers should be confident use the proposed 14-item city brand personality scale for research purposes in China, Germany and the US. When using these scales to research Chinese customers’ city brand perceptions it may be worthwhile to pre-test the excitement and competence scales because of the size of the average variance extracted measures we found for those scales in our Chinese sample. For the same reason, similar precautions may be useful when using the sophistication and competence scales with German customers.

5 Recommendations for event marketing

It is critical for marketers to understand how brand experience affects customers. A customer’s affective and cognitive responses throughout the searching, purchasing, and consumption processes of an event represents the event’s brand experience (Brakus, Schmitt, and Zarantonello 2009). As such, an event’s brand experience is not detached from the city in which it takes place. In this way, the city’s brand, which includes the city’s brand personality, is connected to the event’s brand experience. We provide a theoretically-grounded fourfactor model of city brand personalities. This model provides marketers a way to view the commonality of how individuals experience cities. Our model can complement what is already known about the unique characteristics of a given city when marketing to international customers.

For example, in our Chinese sample, the target city was rated most highly on Excitement and Competence. What our research suggests is that a US customer attending an event in that Chinese city will likely identify with those same factors as prominent elements of the city’s personality. This is because our US sample also recognizes excitement and competence as valid factors of a city personality. Of course, there are other elements of the US customer’s brand experience in the Chinese city that will be unique or new to the customer, but these will be in addition to brand elements the person already associates with cities, in general.

Knowing what city brand personality factors customers tend to perceive as generalizable across cities and what factors are seen as unique to a given city, can help marketers better differentiate and position their events in the cities in which they are located. Knowing that some city brand personality factors are consistent across cultures is particularly helpful in international marketing contexts.

Our research suggests that our four-factor city brand personality model can be measured using only the 14 measurement items shown in Table 2. Thus, marketers can easily and effectively assess how a target city rates on these common city brand personality factors. We provide multiple measures of reliability and a conservative estimate of potential measurement error based on our samples from China, Germany, and the US. Thus, depending on the target audience where these scales are applied, a researcher should be able to anticipate which measurement items, if any, may require additional translating or need to be analysed with more caution when being used in a particular market.

Finally, our four-factor city brand personality model can be applied to understand generational differences in how people experience a city. For example, a given city may have high ratings on excitement by an older generation, but relatively lower ratings by a younger generation. Testing for such differences can help event marketers connect the desired brand experience of their event in a city with its target audience. For example, in the US we tested our scales on an older adult sample and compared the ratings to the student sample. The reliability and validity measures were equally strong, as expected. However, on average the older adults rated the same target city as significantly lower in regards to competence and excitement relative to the younger adults. It is possible that the difference in how each generation experiences the city may influence differences in how each generation experiences or anticipates experiencing an event in that same city.

6 The fundamental relevance of the City Brand Personality Model

Based on the results of the investigation, a variety of benefits of the City Brand Personality Model can be derived.

1.The benefits of the City Brand Personality Model by measuring the personality of a city: Especially for international events it’s important to understand that the city’s personality effects the event experience and vice versa (e. g. Echtner and Ritchie 1991; Kearns and Philo 1993; Ankomah, Crompton and Baker 1995; Um 1998; Richards and Wilson 2004). The City Brand Personality Model is helpful for the event industry and other stakeholders because they can now measure the personality of a city and compare it with other cities. Moreover, it is possible to understand and compare different perceptions of different people from different countries (e. g. perception of Frankfurt/Germany by the Chinese or perception of Shanghai/China by the Germans).

Tab. 1: Overview of Previous Adaptation of Aaker’s (1997) Brand Personality Construct and Scales.

Tab. 2: Proposed City Brand Personality Scale for International Marketing and Evidence of Scale Performance in China, Germany, and United States.

2.The benefits for stakeholders in a city: The results are also interesting for stakeholders of a city, because it helps them to understand their city’s personality. Based on the results, the stakeholder in a city may decide how they can improve the personality of the city for existing events or how they can check out the city and new planned and future oriented events fit together. Furthermore they can understand how a city (e. g. Shanghai) can attract clients from other countries (e. g. Americans).

3.The benefits for the international event industry: The results are interesting for the event industry, because it helps them when deciding where to develop new international events. The city’s personality can have a positive effect on the event. In addition, it helps with deciding which kind of elements of a city’s personality could be implemented into the advertising for the relevant events.

4.The benefits for a brand: The results are interesting for brands (e. g. Mercedes Benz) because it helps them in deciding which city’s personality is more or less relevant for exhibitions due to the high coherence with their own brand.

7 Literature

Aaker, J. L. (1997), ‘Dimensions of Brand Personality’, in: Journal of Marketing Research, 34(3), pp. 347–356

Ankomah, P., Crompton, J. L. and Baker, D. A. (1995), ‘A study of pleasure travellers’ cognitive distance assessments’, in: Journal of Travel Research, Fall, pp. 12–18

Bagozzi, R.P. and Yi, Youjae (1988), ‘On Evaluation of Structural Equation Models’, in: Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), pp. 74–94

Brakus, J.J., Schmitt, B.H., and Zarantonello, L.Z. (2009), ‘Brand Experience: What is It? How is It Measured? Does It Affect Loyalty?’ in: Journal of Marketing, 73(1), pp. 52–68

Crompton .L. (1979), ‘An Assessment of the Image of Mexico as a Vacation Destination and the Influence of Geographical Location upon that Image’, in: Journal of Travel Research, 17(4), pp. 18–23

Ding, S. (2011), ‘Branding a Rising China: An Analysis of Beijing’s National Image Management in the Age of China’s Rise’, in: Journal of Asian and African Studies, 46(3), pp. 293–306

Dolnicar, S. and Grün, B. (2012): ‘Validly Measuring Destination Image in Survey Studies’, in: Journal of Travel Research, 52(1), pp. 3–14

Echtner, C. M. and Ritchie, J. R. B. (1991), ‘The meaning and measurement of destination image’, in: Journal of Tourism Studies, 2(2), pp. 2–12

Ekinci, Y. and Hosany, S. (2006), ‘Destination Personality: an Application of Brand Personality to Tourism Destinations’, in: Journal of Travel Research, 45(2), pp. 127–139

Fornell, C. and Larcker, D. (1981), ‘Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error’, in: Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), pp. 39–50

Go, F., and Zhang, W. (1997), ‘Applying importance-performance analysis to Beijing as an international meeting destination’, in: Journal of Travel Research, 35(4), pp. 42–49

Hankinson, G. (2007), ‘The Management of Destination Brands: Five Guiding Principles Based on Recent Developments in Corporate Brand Theory’, in: Journal of Brand Management, 14(3), pp. 240–254

Hanna, S. and Rowley, J. (2011), ‘Towards a Strategic Place Brand-Management Model’, in: Journal of Marketing Management, 27(5–6), pp. 458–476

Hatch, L. (1994), A Step-by-Step Approach to Using SAS for Factor Analysis and Structural Equation Modelling, Cary: NC, SAS Institute, Inc.

Hunt, J.D. (1975), ‘Image as a factor in tourism development’, in: Journal of Travel Research, 13(3), pp. 1–7

Kaplan, M.D., Yurt, O., Guneri, B., and Kurtulus, K. (2010), ‘Branding Places: Applying Brand Personality Concept to Cities’, in: European Journal of Marketing, 44(9/10), pp. 1286–1304

Kearns, G. and Philo, C. (Eds) (1993), Selling Places: The City as Cultural Capital, Past and Present. Oxford: Pergamon Press

Mayo, E.J. (1973), ‘Regional Images and Regional Travel Behaviour’, In Research for Changing Travel Patterns: Interpretation and Utilization. Proceedings of the Travel Research Association, Fourth Annual Conference, pp. 211–18

Meng, F. and Li, X. (2011), ‘The 2008 Beijing Olympic Games and China’s national identity building’, in: E. Frew & L. White (Eds.), Tourism and national identity: An international perspective (pp. 93–104). New York, NY: Routledge

Mercille, J. (2005), ‘Media effects on image: The case of Tibet’, in: Annals of Tourism Research, 32, pp. 1039–1055

Owen, J. G. (2005), ‘Estimating the cost and benefit of hosting Olympic Games: What can Beijing expect from its 2008 Games?’, in: Industrial Geographer, 3(1), pp. 1–18

Richards, G. and Wilson, J. (2004), ‘The Impact of Cultural Events on City Image: Rotterdam, Cultural Capital of Europe 200’, in: Urban Studies, 41 (10), pp. 1931–1951

Siguaw, J.A., Mattila, A., and Austin, J.R. (1999), ‘The Brand Personality Scale’, in: Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 40(3), pp. 48–56

Sivo, S.A., Fan, X., Witta, E.L., and John, T. (2006), ‘The Search for “Optimal” Cutoff Properties: Fit Index Criteria in Structural Equation Modelling’, in: The Journal of Experimental Education, 74(3), pp. 267–288

Um, S. (1998), ‘Measuring destination image in relation to pleasure travel destination decisions’, in: Journal of Tourism Sciences, 21(2), pp. 53–65

Li, X. and Kaplanidou, K. (2008), ‘The Impact of the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games on China’s Destination Brand: A U.S.-Based Examination’, in: Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 37(2), pp. 237–261

Xu, X. (2006), ‘Modernizing China in the Olympic spotlight: China’s national identity and the 2008 Beijing Olympiad’, in: Sociological Review, 54(2), pp. 90–107

Zhang, L., and Zhao, S. X. (2009), City branding and the Olympic effect: A case study of Beijing. Cities, 26, pp. 245–254

Zhang, J. (2009), ‘Spatial Distribution of Inbound Tourism in China: Determinants and Implications’, in: Tourism and Hospitality Research, 9(1), pp. 32–49