Learning style of Chinese event management students

There is a demand for social development in China by establishing, inter alia, a framework focusing on the employability of university graduates and developing self-directed learners. The key to achieving this would be to gain a better understanding of how learning styles, as one of the cognitive factors, contribute towards academic performance in order to provide meaningful learning experiences. The purpose of this study is to gain an understanding of learning styles and how they influence the academic performance of selected students on the International Event Management (IEMS) programme at Shanghai University of International Business and Economics (SUIBE). As such, the aims of this exploratory quantitative study are to describe and analyse: learning styles; the relationship between learning orientations and learning styles; the relationship between learning styles and academic performance; and the relationship between gender and the learning styles of selected 2nd year 2010 and 2011 IEMS student cohorts (f = 140) at SUIBE. Since the two most dominant learning styles in this study were Divergers and Accommodators, the most dominant learning orientation for these two learning styles was concrete experience. Overall, most of the students in each learning style performed at the satisfactory academic performance level, and females obtained higher scores than their male counterparts in all learning styles.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() IEMS2010

IEMS2010 ![]() 2011

2011 ![]() 140

140 ![]()

![]() (divergers)

(divergers) ![]() (accommodators) ,

(accommodators) , ![]() (concreate experience)

(concreate experience)![]()

![]()

![]()

1 Introduction and context

The overall education status in China gained great progress when China’s reform and “opening-up policies” were launched in 1978. Free compulsory education (including primary and junior middle education) has become the norm in urban and rural areas. In the meanwhile higher education has reached a new stage of popularisation. The development of education has improved the quality of human resources and made a significant contribution to economic growth (The Chinese State Council 2010).

The function of fostering young talents and professionals has been further emphasised as the central task in college and university work (Hao 2005). The higher education system in China has been criticised a great deal for the fact that the graduates cannot meet the demands of industry. The students are weak in their adaptability to society, and the shortage of innovative, practical and versatile professionals has been an acute problem that draws great attention (Li and Lan 2013). Scholars believe that an education system based on graduate employability can help solve the problem (Xie and Song 2005). The core of employabilitybased education is to develop the potential of the students, and transfer the focus of the education process from the teachers’ teaching to the students’ learning (Hao 2005). This is also referred to as “’self-directed learners” where the learners are “learning to be self-aware” (Robotham 1999: 7) and the approach is learner-centred rather than teacher-centred. Pan and Che (2009) maintain that in order to improve the employability of graduates, some provincial universities and colleges should differentiate their position from traditional researchorientated to application-orientated, and focus on the development of skilful talents and professionals. Similar points were proposed by premier Li Keqiang on Feb 26th 2014. Accordingly, the government needs to transform the graduate employment policy by focusing on employability rather than the employment rate, and integrate the employment policy into the higher education process to build a new policy system based on cooperation, colleges and employers (Zhang, Liu, Yu, Jiang and Xue, 2009). Consequently the government is building a new framework including Higher Educational Institutions (HEIs), research institutes, industries and enterprises to better cultivate talent and professionalism in order to meet the demand of social development (The Chinese State Council 2010).

Another serious challenge in the higher education system in China is burnout (Lian, Yang and Wu, 2006) which is mainly due to the following:

–Lack of study purpose (Wang, Zhang and Fu 2010). This lack can be attributed to the extreme desire to get a university certificate so as to be employable. In this process students experience external push from parents to pass the entrance examination to university, known as “Gaokao”.

–Lack of professional commitment (Lian et al. 2006). The high income in certain industries and positions guides the students’ choice of majors such as finance, management, law and informational technology. The future career and income rather than interests and talents become the standard when parents choose majors for their children. The external push from parents and teachers rather than internal interest becomes an important motivation to learning for students in China, and many students do not like their major subjects.

–Low professional adaptability (Wang et al. 2010). Many students get low academic results initially because they battle with establishing a learning strategy and building interpersonal relationships immediately after leaving the monitoring environment and assistance from their parents and teachers in high school.

There is a demand for social development in China by establishing a framework focusing on the employability of the graduates from universities, and developing self-directed learners. Hun, Loy and Milah (2013: 1957) stress that it is important for HEIs to be aware of the ways in which students learn, in order to provide meaningful learning experiences. Furthermore, the quality of students is considered as the key index of higher education effectiveness (Sun, Shen and Guan 2012), therefore learning has received significantly more attention in China since 1980s.

According to Robotham (1999: 1), students: “will develop a way or style of learning, and refine that style in response to three groups of factors: unconscious personal interventions by the individual, conscious interventions by the learners themselves, and interventions by some external agent.” In this study, it is argued that both the unconscious and conscious interventions by the learner and the learner’s response to external interventions are influenced by cognitive and noncognitive factors. Cognitive factors relate to how information is processed, the role of intelligence, learning strategy, and learning style, while the noncognitive factors include personal psychological and environmental elements.

Even though there are many factors that contribute to predicting academic performance, progress and persistence (such as selecting incorrect majors and degree choices, being under- and unprepared, and the lack of study purpose, adaptability, motivation and commitment as well as socio-economic factors), in this study the focus will be on the learning styles as one of the cognitive factors and its relationship with academic performance. Intelligence has been proved to have a direct influence on academic performance. Garavalia and Gredler (2002); Huo, Cai, Zou, Feng, Zhu, Xu, Geng, Zhang and Mao (1997); Rosander and Bäckström, (2012: 820) have found that the cognitive factor “learning style” directly influences students’ academic performance The cognitive factor, learning style is among predictors of academic performance (Chang, Kang and Wang 2005; Drysdale, Ross and Schulz 2001; Gauss 2002; Kvan and Yunyan 2004; Lu 2005). Wu (2004) examined the relationship between learning strategy, learning style and learning achievement, and found that the research supported the direct influence of both learning strategy and learning style on students’ learning achievement. Even though multiple ways have been used to describe students’ learning and studying processes (Tait and Entwistle 1996: 100), the most commonly used are students’ learning styles (Hun et al. 2013: 1958). Andreou, Andreou and Vlachos (2008: 665) describe a learning style as “a student’s preferred mode of perceiving, organising and retaining information”. A student responds to and uses stimuli in their learning environment through behaviours incorporating their individual learning style (Drysdale et al. 2001: 273).

Even though the cognitive factor (learning style) directly influences students’ academic performance, it is important to note that the emotional factors (learning willingness and achievement motivation) indirectly influence academic performance via cognitive factors.

Students’ learning attitude (Yin 2008; Zhang and Geng 2009), learning motivation (Huo, et al. 1997; Tu 2013), personality types (Gauss 2002), goals and sub-goals (Riordan 2002), coping strategies and study skills (Abatso 1982) are predictors of academic persistence, and significant influences on academic performance. Positive affective variables such as selfesteem (Tu 2013) and perceived self-efficacy (McSorley 2002) can help improve academic performance, while negative affective variables such as anxiety about difficulties (Nie, Zhao and Shan 2000; Tu 2013) are negatively related to academic success.

The financial and educational status of the family is also proved to influence students’ academic performance. Huang and Xin (2007) argue that the family background significantly influence students’ academic achievement; students from families with an ample collection of books showed higher performance than their classmates with fewer books. Sun, et al. (2012) found students’ family financial status and Party membership significantly influence their academic performance.

However, for the purpose of this study the focus will be on gaining an understanding of the cognitive factor, learning styles, and their influence on academic performance of selected students in the International Event Management (IEMS) programme at the Shanghai University of International Business and Economics (SUIBE).

SUIBE has established extensive partnerships with its overseas counterparts from more than 80 countries, and now offers 12 joint programmes in cooperation with institutions of higher education in Australia, the United Kingdom, Canada and Germany. One of these is the International Event Management Shanghai (IEMS), a cooperative programme between SUIBE and Osnabruck University of Applied Science (HSOS) from Germany?which has the most developed MICE industry. IEMS is one of the first two programmes that got the approval on event management from the Ministry of Education in China in 2000. In addition, it is the first international cooperative programme of event management in China. The teaching activity is conducted by faculty members from HSOS and SUIBE. Fifteen core courses of IEMS modules are offered in English, which are cooperated by both German professors and Chinese faculty members. In the fourth year, the students must write a thesis in English and pass the oral defence given by both Chinese and German supervisors, to get the degree from both universities. After the successful implementation of the IEMS programme over the past ten years, more than four hundred students have graduated from both SUIBE and HSOS. IEMS has now built its human resource development system for event management talents, which covers the key processes in event management. The system also covers the cooperation with industry and enterprises in event industry.

The purpose and aims of this study will be provided in the next section. In this chapter an overview of theoretical perspectives on learning styles and learning orientations, learning styles and academic performance, and learning styles and gender will be given. The research methodology of this study, findings and concluding remarks are also given.

2 Purpose and aims of the study

The purpose of this study is to gain an understanding of learning styles and their influence on academic performance of the selected students in the International Event Management (IEMS) programme at the Shanghai University of International Business and Economics (SUIBE).

More specifically, the primary aims of this study are to describe and analyse the following:

–The learning styles of the selected IEMS students at SUIBE;

–The relationship between learning orientations and learning styles of selected IEMS students at SUIBE;

–The relationship between learning styles and academic performance of the selected IEMS students at SUIBE;

–The relationship between gender and learning styles of selected IEMS students at SUIBE.

A more comprehensive overview of the learning styles will be provided in the next section.

3 Theoretical overview on learning styles

3.1 Learning style frameworks and theories

Extensive research has contributed towards the development of conceptual frameworks for better understanding of learning preferences, approaches to knowledge acquisition, information processing, and learning styles. Particularly relevant to this study are the varioius conceptual learning styles frameworks and theories that have been used to describe students’ preferred modes of learning (Komarraju, Karau, Schmeck and Avdic 2011: 472, Rodrigues 2005: 610). Some widely used learning style frameworks and theories are the Approaches to Studying Inventory (ASI), Inventory of Learning Processes (ILP) and Learning Styles Inventory (LSI) based on Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory (ELT).

The ASI was originally developed by Marton and Säljö (1976, cited in Diseth and Martinsen 2003: 196) and is used to explore interrelationships between various factors leading to differences in learning and studying. The ILP developed by Schmeck, Ribich and Ramanaiah (1977, cited in Komarraju et al. 2011: 474), is a widely used learning style framework that is able to show which learning strategies can help students improve their academic performance. The ELT was developed by Kolb (1984, cited in Kolb and Kolb 2005: 194) and, according to Kayes (2005: 250) and Rodrigues (2005: 610), describes different but interdependent learning styles according to the different learning abilities of students (Kayes 2005: 250; Rodrigues 2005: 610). Descriptions of different learning styles as identified by the ASI, ILP and ELT learning style frameworks and theories are summarised in Table 1.

Although there are various frameworks and theories of learning styles (Komarraju et al. 2011: 472) – three of which are described in Table 1 – Kolb’s ELT has been the most influential (Andreou et al. 2008: 665) and is widely used in learning styles research at the tertiary level across multiple academic disciplines (Kolb and Kolb 2005: 196; Kvan and Yunyan 2005: 22; Drysdale et al. 2001). Kolb developed the learning styles inventory (LSI) to validate his ELT theory. Kolb developed the first LSI instrument in 1976, after which further refinement of LSI-2 appeared in 1985, LSI 2A in 1996, and the LSI-3 in 1999 (Kayes 2005: 250). For the purpose of this study, an amended version of the LSI-3 marketed by BK One (BK One Corporate Training 2011) was used to determine the students’ preferences for the different orientations which determine their preferred learning styles. According to Lynch, Woelfl, Steele, and Hanssen (1998: 62) the LSI is a “well-validated method for assessing learning style preferences” in a variety of situations, and it has been applied in China by Kvan and Yunyan (2004: 19).

3.2 Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory (ELT)

The ELT portrays the learning process as a cycle during which a learner will recursively experience, reflect, think and act in response to the requirements of an encountered learning situation (Kolb and Kolb 2005: 194). The ELT therefore proposes four interdependent orientations to learning, namely, concrete experience (feeling/experiencing), reflective observation (reflecting/observing), abstract conceptualisation (thinking/facts) and active experimentation (acting/performing) (Kayes 2005: 250).

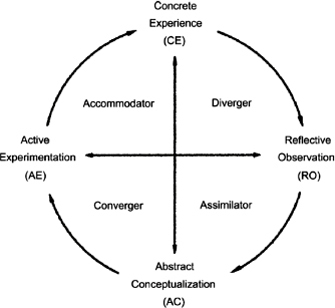

According to the ELT, learners will process information along two dimensions, namely the vertical and horizontal dimensions. As shown in Image 1, the vertical dimension (axis) provides insights into how students assimilate information either through concrete experience (CE) by means of emotions (feelings and people involved) or abstract conceptualisation (AC) by means of thoughts and facts (objective and factual). How students understand or input information is further processed or transformed through either reflective observation (RO) by reflecting on the experience (introvert) or active experimentation (AE) by acting out the experience (extrovert), as shown by the horizontal dimension (axis) in Image 1 (Rodrigues 2005: 610). An orientation towards concrete experience (feeling/experiencing) entails learning by engaging through direct experience, emphasising experiential learning, whereas an orientation towards abstract conceptualisation (thinking) entails learning through developing analytical theories and concepts to create meaning and direct action (Kayes 2005: 250; Lynch et al. 1998: 62). On the other hand, an orientation towards reflective observation (reflecting) entails learning through considering multiple perspectives which include existing experience and new knowledge, before executing an action, while an orientation towards (action) active experimentation describes a preference for learning through taking action and risk taking (Kayes 2005: 250; Lynch et al. 1998: 62).

Some positive researchers have found that learning styles and orientation are strongly influenced by culture. Research by Joy and Kolb (2009) shows that people from countries that are high in in-group collectivism, institutional collectivism, uncertainty avoidance, future orientation, and gender egalitarianism, tend to be dominant in the abstract learning orientation (AC). Joy and Kolb (2009) also found that people from countries that are high in in-group collectivism, uncertainty avoidance, and assertiveness, are more dominant in the reflective learning orientation style (RO). Researchers from Asia are of the opinion that the learning style preference is culture-sensitive, and that the scales developed in the USA need to be further validated (Hyland 1993; Isemonger and Sheppard 2007).

Although learners will use aspects of the four orientations to learning during a learning process, they tend to develop a preference for using one or two of these orientations, which then become their particular learning style (Kayes 2005: 250). The ELT thus identifies four particular learning styles which are determined by preferences for the different orientations to learning (Kvan and Yunyan 2005: 21). The four learning styles according to the ELT as measured by the LSI are therefore: diverging, assimilating, converging, and accommodating (Andreou et al. 2008: 665).

Learners with a diverging learning style have a preference for concrete experience and reflective observation learning orientations. Rather than take action, divergers prefer to consider situations from many different perspectives and come up with new ideas (Kayes, 2005: 250; Kvan and Yunyan 2005: 21). Consequently these learners, who are reflective in nature, are inclined to need more time to consider and process the different perspectives before taking action. Divergers have been referred to as “creative learners” (Lynch et al. 1998: 62) who are likely to specialise in the arts discipline (Kolb and Kolb 2005: 196).

The assimilating learning style uses the reflective observation and abstract conceptualisation learning orientations. Assimilators are able to understand and concisely organise information from many sources, are logical, and value sound theories (Kvan and Yunyan 2005: 21), and are referred to as the theorists. These learners prefer developing concepts or unifying theories inductively to explain their observations (Lynch et al. 1998: 62). Consequently, learners with the assimilating learning style show more interest in concepts and theories rather than people, leaning towards specialising in information and science disciplines (Kolb and Kolb 2005: 197).

The converging learning style emphasises the abstract conceptualisation and active experimentation learning orientations. Convergers are therefore learners who have a preference for practical problem solving through deductive reasoning, are good at decision making, are comfortable with taking action as part of their learning process (Kayes 2005: 250; Kvan and Yunyan 2005: 21; Lynch et al. 1998: 62), and pragmatic in nature. As convergers prefer to deal with technical tasks rather than people, they tend to lean towards the specialist and technology disciplines (Kolb and Kolb 2005: 197).

Figure 1: The Experiential Learning Cycle, Learning Orientations and Learning Styles. (Source: Adapted from Kolb, 1984 cited in Kvan and Yunyan 2005: 21).

Lastly, the accommodating learning style uses the active experimentation and concrete experience learning orientations. Learning for accommodators therefore typically involves taking action, relying on their intuition rather than logical analysis, (Kayes 2005: 250; Kvan and Yunyan 2005: 21) and are activists in nature. Accommodators are also comfortable with new experiences and commit quickly to action and leadership roles, and tend to be more effective in action-orientated disciplines like marketing and sales (Kayes 2005: 250; Kolb and Kolb 2005: 197). A summary of these four learning styles can seen in Table 1.

Based on their preference for concrete experience or abstract conceptualisation and reflective observation or active experimentation, a learner can thus be classified into one or two of these learning styles (Kvan and Yunyan 2005: 21). The four learning orientations and resultant learning styles can be represented by an experiential learning cycle, as shown in Image 1. Kolb and Kolb (2005: 194) describe experiential learning as a cyclical learning process that will use the four learning orientations, albeit to varying degrees. Emphasised preference for a certain learning stage (orientation), results in an individual learner’s particular learning style (Kvan and Yunyan 2005: 21).

3.3 Managing the learning process using the ELT

As mentioned previously, the ELT can be used to assess learners’ individual learning styles by using Kolb’s Self-report instrument, the Learning Style Inventory (LSI). When learners are conscious of their individual learning styles, they focus more on beneficial habits that will lead to a more effective learning experience (Lynch et al. 1998: 66), facilitate better understanding of fellow students, enhance team work, and assist in task completion and procrastination (Connelly 2010). Being aware of one’s learning style, according to Andreou et al. (2008: 672), can lead to improved attitudes, behaviour and motivation due to increased self-knowledge and awareness. The increased self-awareness, in turn, contributes to academic and social integration, and has implications for level of confidence and career development (Connelly 2010). As such, students should be empowered to identify and address developmental areas in their learning styles, and consequently have a sense of control over their academic performance and social integration.

From the academic faculty’s perspective, knowledge of learning styles of their students could assist Faculty members in different ways such as facilitating the proposed shift in teaching orientation towards a student-centred approach, as highlighted in the introduction and context of this chapter, and considering different teaching and assessment methods. In this regard a shift would be required in approaches to learning from a low quality (surface) learning to a high quality (deep) learning approach. The shift would be towards a student-focused deeper learning experience away from the narrow focus on solving particular problems to where “the interest of the individual is not confined to an instrumental approach to learning where task completion is the only aim, there is also on interest in the learning process” (Robotham 1999: 2). In deep learning, the intention is to understand the material as motivated by an interest in (Diseth and Martinsen 2003: 196) and looking for meaning in (Rosander and Bäckström 2012: 820) the subject matter, and to substantiate with evidence. According to Diseth and Martinsen (2003: 196), operation and comprehensive learning strategies are included in deep learning.

On the other hand, surface learning refers to operation learning and the focus is on reproducing learning material by means of different forms of rote learning (Diseth and Martinsen 2003: 196) and memorising content in isolation without understanding the content (Rosander and Bäckström 2012: 820). Deep learning has been positively related to high achievement (Diseth and Martinsen 2003: 196) and academic success (Entwistle and Wilson, 1977, cited in Cassidy and Eachus 2000: 311). Faculty members could be more informed on how to adjust their methods of instruction, namely teaching methods and assessment, to accommodate the most dominant learning styles in a cohort of students so as to encourage deep learning. It has been asserted that matching the methods of instruction with learning styles, optimises the students’ learning and academic performance (Vawda 2005: 11; Andreou, et al. 2008: 672; Charkins, O’Toole and Wetzel 1985; Dunn 1984). However, it is cautioned that there should be a balance between structuring methods of instruction according to the dominant learning styles versus a balanced approach across the learning styles. There are various reasons for this, that fall beyond the scope of this chapter. However, it is important to note that there are strong arguments for an instructional delivery approach that is more balanced across the learning styles, enabling greater learning versatility and contributing to the development of a student-centred approach (Pedrosa de Jesus, Ameida, Teixeira-Dias and Watts 2006: 109; Ruble and Stout 1993; Friedman and Alley 1984; Cronbach and Snow 1977).

Kolb and Kolb (2005: 196–197) propose that: divergers learn most effectively in groups, benefit from personal feedback, and enjoy activities such as brainstorming; assimilators benefit from readings, lectures, using analytical models, and need time for reflecting before responding; convergers learn best through exploring new ideas, simulations, practical assignments and solving technical issues; and accommodators benefit from group assignments, field work and exploring different ways of accomplishing tasks. Developing habits that are beneficial to one’s particular learning style could therefore lead to enhanced academic performance (Lynch et al. 1998: 66).

4 Learning style and academic performance

Past research has established that learning styles and approaches to the learning process have a bearing on the academic performance of learners (e. g. Hun et al. 2013; Komarraju et al. 2011; Kvan and Yunyan 2005; Cassidy and Eachus 2000; Drysdale et al. 2001; Lynch et al. 1998). Learners’ dominant learning styles can therefore affect academic performance (Rosander and Bäckström 2012: 825). Furthermore, learning style differences can be observed across disciplines (Kolb and Kolb 2005: 195) as briefly discussed earlier in the section on Kolb’s ELT.

Lynch et al. (1998) for instance, used Kolb’s LSI to measure the learning styles of learners and to determine the relationship between learning styles and academic performance. The research by Lynch et al. (1998) explored the learning styles of third-year medical students and found that convergers and assimilators (with their preference for abstract conceptualisation) performed better on single best answer multiple choice examinations. Based on this result, medical students were therefore found to employ analytical and abstract approaches to learning, which were beneficial for their discipline. Kolb and Kolb, (2005: 202–203) further propose that learning in the management discipline, is a scientific and largely text-driven learning process that emphasises theory. In this regard, the management discipline is seen to emphasise an abstract learning orientation. A study by Drysdale et al. (2001) on the cognitive learning styles and academic performance of 19 first-year university courses confirms that there is a significant correlation between academic performance and learning styles. Their study further confirms that maths-related disciplines are better suited to learners who think logically and sequentially, and that all the learning styles are suited to the liberal arts and social sciences.

5 Learning style and gender

As personal factors such as gender can have an influence on the learning process (Vermunt 2005: 205, 207), learning style research has also examined gender differences with regard to preferences for particular learning styles. For example, Philbin, Meier, Huffman and Boverie (1995) found that female learning styles were predominantly divergers or accommodators and they preferred non-traditional learning and concrete learning experiences, while males were more likely to be assimilators and preferred traditional and analytical learning environments. Andreou et al. (2008) in their study of English 2nd language learners confirmed that females leaned more towards a divergent learning style than the males. The study by Peng, Ma and Li (2006) confirmed these findings. Peng, et al. (2006) found significant gender difference in the cognitive styles of the university students: male students preponderated in the thinking and sensing (AC), female students preponderated in the feeling and intuition (CE). A study by Dee, Nauman, Livesay and Rice (2002) of Biomedical engineering students in the Netherlands confirms the findings of Peng et al. 2006).

Zhou (2007) found that female and male students showed different learning styles such as visual style, hands-on style, impulsive style and teacher-independent style, and explained the possible reason from the perspective of socialisation. Females were also found by Vermunt (2005: 229) to be more social and less individualistic in their learning. Finally, Rosander and Bäckström (2012: 825) found that females were more motivated by a “fear of failure” and “aim of qualification”, in their academic performance, which resulted in adopting a surface approach to learning. It is also pointed out that studies that do not find differences in learning styles between genders could be attributed to a variety of factors such as sample size, mixture of students, and type of instruction (Jones, Reichard and Mokhtari 2003).

6 Research methodology

The positivistic research paradigm was followed, in which the data collected was quantitative in nature (Collis and Hussey 2014: 44). As such an exploratory and descriptive approach was used to describe and analyse the learning orientations, styles and academic performance of the 2nd year IEMS students at SUIBE.

A non-probability convenience sampling was used in identifying all the 2nd year 2010 and 2011 IEMS cohorts at SUIBE (f = 140). The reasons for selecting the past two 2nd year cohorts were that their academic results from their 1st semester in their 2nd year of study could be calculated and they had had time to settle into university learning after having completed their first year of study. The results from this study could provide useful insights for their own study and for faculty members to consider in the second semester of the 2nd year and the 3rd year of study. Participation was voluntary and with consent. Since the data gathered over the two years was similar, only the overall findings are reported in this chapter.

As previously mentioned, the adapted version of Kolb’s LSI-3, marketed by BK One (BK One Corporate Training 2011), was used in this study. This research instrument was administered during the first semester of the 2nd year of study. Students were requested to respond to 36 statements by selecting one of two statements from columns A or B and C or D that most closely described them. The first 18 statements pertain to the horizontal axis, as shown in Image 1, and represent the continuum from being an AE to RO (active – observer continuum).

The scoring for these statements is obtained by subtracting B from A (A-B). A positive AB score is indicative of a more active orientation (AE) while a negative (B-A) score is indicative of a more reflective (RO) learning style. The second 18 statements pertain to the vertical axis, as shown in Image 1, and represent the continuum from being an AC to CE (abstract – concrete). The scoring for these statements is obtained by subtracting D from C (C-D). A positive CD score is indicative of a more abstract orientation (AC) while a negative (D-C) score is indicative of a more concrete (CE) problem-solving and learning style. The AB (AC-CE) and CD (AE-RO) scores are plotted on perpendicular axes, as shown in Image 1, placing the respondent into one of the four quadrants. Each of these quadrants corresponds to one of Kolb’s four learning styles, namely, convergence, divergence, assimilation, and accommodation. By joining the two learning orientation scores with a line, the quadrant of the most dominant learning style is shown. The scores from each column were captured into an Excel spreadsheet, and the mean values for each learning orientation and learning style were calculated for the two cohorts of students as a whole. According McFarland (1997 cited in Vawda 2005: 65) the reliability of this LSI instrument ranges from 0.52 to 0.86. Consistent with previous research, Kayes (2005: 254, 255-6) provides evidence for the internal reliability of Kolb’s LSI-3 scales, with Cronbach’s alpha scores for the four dimensions ranging between 0.77 to 0.82 and the “combined scores for AC-CE and AE-RO of 0.77 and 0.84 respectively”. There is also support for the internal construct validity of Kolb’s LSI-3 instrument (Kayes 2005: 256). One potential limitation of the measuring instrument is its ipsative nature, where respondents have to compare two options and then choose the most preferred, also referred to in psychology as “forced choice” scale. Consequently a “high score on one dimension results in a correspondingly low score on another dimension” (Kayes 2005: 252). Despite this potential limitation it is accepted that ipsative measures “pose few problems when an instrument is used for self-diagnosis” (Kayes 2005: 253), which was the case in this study.

Assessment of the academic performance was based on the first semester of the second year of each cohort’s Grade Point Average (GPA) scores. The GPA score is calculated by determining the average score for each student, based on the class and exam mark for all the courses completed in the semester in which study was undertaken. The types of assessments range from single best answers, multiple-choice questions to assess knowledge, short case scenarios, to presentations and group assignments. The GPA mean scores for both cohorts are categorised according to the following groupings: below 60 per cent – fail; 60 to 69 per cent – pass; 70 to 79 per cent – satisfactory; 80 to 89 per cent – good; and 90 to 100 per cent – excellent.

Data was analysed by means of descriptive and inferential analyses. Given the exploratory and descriptive nature and the small sample of respondents, descriptive statistics such as mean scores and frequency counts which were converted to percentages were tabulated to describe the learning styles, the cross tabulation of learning styles with a academic performance, while mean scores were used in the cross tabulation of learning orientations with learning styles. The frequency counts were used to explain the cross tabulation of learning styles with gender. The relationship between the learning styles and academic performance was analysed by using regression analyses. All the data was captured into an Excel spreadsheet and the regression analysis was done by using SPSS 19.0.

7 Findings

A response rate of 94,28 per cent was received based on the participation of 132 out of 140 students from both the 2010 and 2011 cohorts. Overall there were 96 female and 36 male respondents.

As mentioned previously, only the overall findings for the two cohorts will be reported on in this chapter.

The distribution of the four learning styles is presented in Table 2. From Table 2 it can be seen that that all four learning styles were represented in the whole sample. Most of the students’ dominant learning style was Diverger (f = 73, 55 per cent), followed by 40 students who were Accommodators (30 per cent), 13 Assimilators (10 per cent) and the six Convergers (5 per cent). A majority of studies (Kvan and Yunyan 2005; Lynch et al. 1998; Kolb 1981) find all four learning styles to be represented, although they may differ on the dominant learning style and be influenced by the discipline of study (Kolb and Kolb 2005).

Tab. 2: Learning styles for whole sample.

| f | per cent | |

| Diverger | 73 | 55 |

| Assimilator | 13 | 10 |

| Converger | 6 | 5 |

| Accommodator | 40 | 30 |

| Total | 132 | 100 |

The learning orientations are cross-tabulated with the learning styles in Table 3 based on mean scores. As shown in Table 3, the Divergers seem to be using Reflective Observation (RO) (mean score 5.28) the most, followed by Concrete Experience (CE) (mean score 4.86), Active Experimentation (AE) (mean score 4.01) and Abstract Conceptualisation (AC) (mean score 3.88). Assimilators seem to use more Reflective Observation (RO) (mean score 7.23) which means that they are tentative and reflective in their learning. The Assimilators combine Reflective Observation (RO) with Abstract Conceptualisation (AC) (mean score 6.92) and use significantly less Active Experimentation (AE) (mean score 3.23) and Concrete Experience (CE) (mean score 2.54). Convergers also seem to use more Active Experimentation (AE) (mean score 6.67) which suggests that they are performers, action orientated, who learn through experimentation. The Convergers seem to closely combine Active Experimentation (AE) (mean score 6.67) with Abstract Conceptualisation (AC) (mean score 6.00) which indicates that they are factorientated, relying on logical thinking and rational evaluation. To a lesser extent the Convergers use Reflective Observation (RO) (mean score 3.33) and Concrete Experience (CE) (mean score 3.0) on an equal basis. Accommodators use Active Experimentation (AE) (mean score 7.00) which means that they are hands-on and learn through experimentation and Concrete Experience (CE) (mean score 5.93) most, which means they combine an action orientation with an experienced based approach to learning. These learners use Abstract Conceptualisation (AC) (mean score 4.00) and Reflective Observation (3.25) significantly less in their learning.

Tab. 3: Cross tabulation of learning orientations with learning styles.

7.1 The relationship between learning styles and academic performance

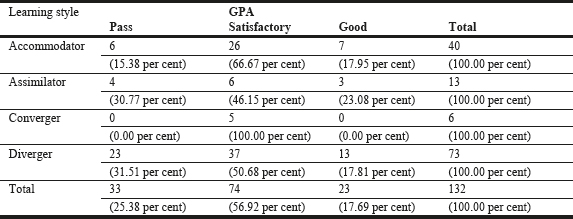

Table 4 shows the descriptive cross tabulation for the four learning styles and the academic performance according to the GPA categories. It should be noted that none of the students failed or received excellent GPA scores. From Table 4 it is evident that in all four learning styles, most of the students in each category performed at the satisfactory level as follows: 50.68 per cent of divergers; 46.17 per cent of the assimilators; all the convergers; and 66.67 per cent of accommodators. Relative to the other learning styles, a higher percentage of the assimilators (23.08 per cent) performed in the good category. Overall, there was no real trend.

Tab. 4: Cross tabulation of learning styles and academic performance.

Table 5 shows the results of the regression analysis between the four learning styles and the academic performance according to the GPA categories. Based on the regression, no significant relationships between learning styles and academic performance were found, as shown in Table 5.

Tab. 5: Correlation matrix between learning styles and academic performance.

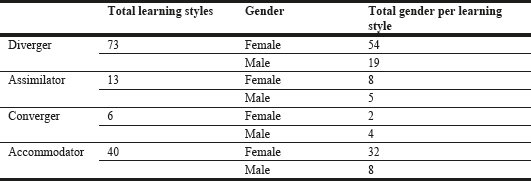

The descriptive statistics for the whole sample (Table 6) on gender distribution for learning styles reveals that the learning styles of both the females and males were predominantly divergent (female = 54; male = 19), followed by the accommodator learning style (female = 32; male = 8) with the least dominance in the converger learning style (female = 2; male = 4). In the assimilator learning style, the females were more present than the males (females = 8; males= 5). The finding in the current study that females are predominantly divergers or accommodators confirms previous research by Andreou et al. (2008), Peng et al. (2006), Philbin et al. (1995). Given these dominant learning styles, the predominant cognitive styles of the female students in this study would be in the feeling and intuition (CE) domain. The findings pertaining to the male students in the current study are not confirmed by previous research since most of the males’ predominant learning styles were similar to the females in this study, namely divergers and accommodators.

Tab. 6: Cross tabulation of learning styles and gender.

8 Conclusion

A summary of the main findings in terms of learning styles, learning orientations, the relationship between learning styles and academic performance as well as the relationship between learning styles and gender, will be presented in this section together with concluding implications for the students and faculty members.

Learning styles were not equally distributed among the IEMS students participating in this study. The majority (55 per cent) were divergers, followed by accommodators (30 per cent), assimilators (10 per cent) and convergers (5 per cent).

As mentioned previously, the divergers (CE and RO) are the reflectors, acquire knowledge through using their intuition to generate new ideas, and are imaginative and creative. They are able to see the big picture. While the ability to see the bigger picture and multi-task is a strength, these learners need more time to consider and process the different perspectives before taking action, lose sight of detail, and are inclined to become distracted and somewhat disorganised in keeping notes. It is pointed out by Kolb and Kolb (2005: 196) that divergers are likely to specialise in the arts discipline. While this assertion concurs with the creative aspects in organising events or participating in projects, the ability to begin with a project could be challenging because of the many alternatives, and this would complicate decision making. Kolb and Kolb (2005: 196–197) propose that: divergers learn most effectively in groups, benefit from personal feedback, readings, lectures, using analytical models and need time for reflecting prior to responding and enjoy activities such as brainstorming.

Concentration is increased by using diagrams, visuals and examples, rather than detailed theory.

The accommodators (AE and CE) prefer to learn through taking action (activists), take risks and acquire knowledge through intuition rather than logical analysis. Accommodators are motivated and energetic learners whose greatest strength is the ability to be fully involved in new experiences, able to take action quickly (work quickly) and rely on information from others. Their strengths could, however, contribute to their not finishing a task because they are involved in too many tasks from a wide range of interests and experiences (Connelly, 2010). These learners will adopt a more shallow orientation to completing assignments and tasks, leave things to the last minute and, like the divergers, need to plan better. This learning style will facilitate “getting the work done” in the event industry, and need leadership roles. Due to their fractured learning approach and task completion, accommodators benefit from group assignments, field work, small group discussions, games, and exploring different ways of accomplishing tasks with other people, especially on projects.

The two least two dominant styles were the assimilators (theorists) (RO and AC) and the convergers (pragmatists) (AC and AE), with the converger being the most under-represented in this study. Assimilators (RO and AC) learn by using multiple sources of information which are logically analysed in a step-by-step process and then on planning and reflecting. Consequently they need time to think and prepare, and find it difficult to complete a task. Assimilators benefit from readings, lectures, case studies, theoretical readings, reflective exercises and using analytical models and need time for reflecting before responding. A systematic analysis of theory in an impersonal learning environment is preferred. On the other hand, Convergers (AC and AE) prefer to learn through solving practical problems, get things done, are results-orientated and need to improve their interpersonal relationships. Convergers learn best through exploring new ideas, simulations, practical assignments and prefer solving technical issues.

Both the divergers and accommodators (dominant learning styles) learn through feelings and intuition rather than abstract conceptualisations (objective facts). This finding is contrary to the research by Joy and Kolb (2009) indicating that the abstract learning orientation (AC) should be dominant in China. This phenomenon could be attributed to the cultural values of the students in China and the role of Confucianism. In contrast, it is interesting to note that in research done in the USA, the dominant learning styles seem to be convergers and assimilators (Lynch et al. 1998: 64). A study done by Vawda (2005: 72) and in the HE context in South Africa confirmed the results of this study for students in the Management sciences, namely that the two dominant learning styles were accommodator and diverger.

The question can thus be posed whether the Faculty members who teach on the IEMS programme at SUIBE should focus on accommodating the two dominant learning preferences, or whether a more balanced approach needs to be considered where learners are developed and stretched to improve their underdeveloped learning style, thereby achieving greater learning versatility and contributing to the development of a student-centred approach. The latter would be more aligned with the government in China’s new framework to better cultivate talent and professionals in order to meet the demand of social development in China.

Since the two most dominant learning styles in this study were Divergers and Accommodators, the most dominant learning orientation for both these learning styles was concrete experience (CE). Consequently, the respondents gather and understand information through concrete experience (CE) by means of emotions (feelings and people involved) which represents a receptive experience-based approach to learning rather than through abstract conceptualisation (AC) which represents an analytical conceptual logical approach by using thoughts and facts (objective and factual). The respondents further processed the gathered information primarily through either reflective observation (RO) which indicates reflective learning based on experience (introvert) or active experimentation (AE), indicating that learning takes place by acting out the experience (extrovert) based on taking risks.

Overall there was only one trend in the relationship between learning styles and academic performance, namely that most of the students in each learning style performed at the satisfactory academic performance level. Previous research by Vawda (2005) at a HEI in South Africa could not establish a relationship trend between the learning styles of university students from different faculties and academic performance.

In all the learning styles the females scored higher than their male counterparts. It should be noted that there is a bias in this finding, since most of the students in these cohorts of IEMS students are female. Both the females and the males’ dominant learning styles were divergers and accommodators with a concrete experience orientation. The finding pertaining to the males is contrary to previous research and could possibly be explained in terms of an Asian cultural orientation and the relatively smaller number of male students in the cohorts.

A number of limitations with regard to the generalisation of the results of this study need to be mentioned. Firstly, these results were derived from two 2nd year cohorts of the IEMS programme and may not be representative of all the students in the IEMS programme or students in similar programmes at other universities. Secondly, the exploratory and descriptive nature of this study and the use of convenience sampling is limiting. Thirdly, the small number of students who could be classified as convergers (5 per cent) and assimilators (10 per cent) must also be acknowledged. Consequently very little could be said about their performance patterns, and the findings in this study pertain mainly to the divergers and accommodators. Fourthly, due to the small sample size, and wide spread of results in the GPA scores, no correlations could be found between learning styles and academic performance, despite previous research indicating that the cognitive prototype, including learning styles, directly influences the students’ academic performance.

Despite these limitations, the present study does have implications for the IEMS programme at SUIBE. Firstly, knowledge of the learning styles and increased self-awareness of the strengths and weaknesses of each learning style and the learning orientations provides students with insights into their own conceptual prototype. Consequently students are empowered to identify and address non-productive behaviours and strengthen beneficial behaviours. As a result they should have a more informed sense of control over their academic performance and social integration, which has implications for their approach to learning (surface or deep learning) and career development. Secondly, considering the increased attention being paid to the learning effect as a significant index of quality students in higher education in China since the 1980s, this study provides insights into the learning styles of the selected cohorts in the IEMS programme and some guidance on the appropriate teaching and assessment methods according to the different learning styles. Consequently, being more aware of the ways in which students learn provides the basis for meaningful learning experiences on the IEMS programme at SUIBE and would facilitate the proposed shift in teaching orientation towards a student-centred approach. Thirdly, while it could be argued that Faculty members could use the insights gained to adjust the content and method of instruction to accommodate the most dominant learning styles of the students, it is cautioned that there should a balanced approach across the learning styles. As such, it is suggested that a balanced approach across the learning styles enables greater learning versatility and contributes to the development of a student-centred approach.

Recommendations for future research:

–Further validating the learning styles instrument to the Asian context because of the cultural sensitivity in learning styles;

–Determining the impact of culture on teaching and learning methods;

–Assessing the correlation between learning styles and approaches to learning, including a strategic learning approach;

–Further investigate the correlation between approaches to learning, learning styles and motives as predictors of academic achievement; and

–Administer a culturally sensitive learning styles instrument, including some of the mentioned aspects to all the IEMS students at SUIBE in order to determine the correlation with academic performance more accurately.

9 Literature

Abatso, Yvonne (1982), Coping strategies: Retaining Black Students in College, Atlanta, GA: Southern Education Foundation

Andreou, Eleni, Andreou, Georgia and Vlachos, Filipos (2008), ‘Learning Styles and Performance in Second Language Tasks’, in: TESOL Quarterly, 42 (4), pp. 665–74

BK One Corporate Training (2011), Learning Style Indicator. Online: http://www.bkone.co.in/LrngStyleIndicator.asp (accessed on 9 September 2014)

Cassidy, Simon and Eachus, Peter (2000), ‘Learning Style, Academic Belief Systems, Selfreport Student Proficiency and Academic Achievement in Higher Education’, in: Educational Psychology, 20 (3), pp. 307–22

Chang, Xin, Kang, Ting Hu, and Wang, Pei (2005), ‘The Influence of Cognitive and Emotional Factors on University Students’ Achievements in English Learning’, in: Psychological Science, 28 (3), pp. 727–730

Charkins, RJ, O’Toole, Dennis and Wetzel, James (1985), ‘Linking Teacher and Student Learning Styles with Student Achievement and Attitutes’ in: The Journal of Economic Education, 16 (2), pp. 111–120

Collis, Jill and Hussey, Roger (2014), Business Research: A Practical Guide for Undergraduate and Postgraduate Students, London: Palgrave MacMillan

Connelly, Ruth (2010), Additional Information : Unlocking my Learning Potential and Discovering my Learning Style, Unpublished workshop paper, Student Counselling, Career and Development Centre, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, Port Elizabeth, South Africa

Cronbach, Lee and Snow, Richard (1977), Aptitudes and Instructional Methods: A Handbook for Research on Interactions, New York: Irvington

Dee, Kay, Nauman, Eric, Livesay, Glen, A and Rice, Janet (2002), ‘Research Report: Learning Styles of Biomedical Engineering Students’ in: Journal of Engineering Education, 20 (8), pp. 110–1106

Diseth, Åge and Martinsen, Øyvind (2003), ‘Approaches to Learning, Cognitive Style, and Motives as Predictors of Academic Achievement’, in: Educational Psychology, 23 (2), pp. 195–207

Drysdale, Maureen, Ross, Johnathan and Schulz, Robert (2001), ‘Cognitive Learning Styles and Academic Performance in 19 First-Year University Courses: Successful Students Versus Students at Risk’, in: Journal of Education, 6 (3), pp. 271–89

Dunn, Rita (1984), ‘Learning Style: State of the Science’, in: Theory into Practice, 23 (1), pp. 10–19

Entwistle, Noel and McCune, Velda (2004), ‘Measuring Studying and Learning in Higher Education: Conceptual and Methodological Issues’ in: Educational Psychology Review, 16 (4), pp. 325–45

Entwistle, Noel and Wilson, John (1977), ‘Degrees of Excellence: The Academic Achievemetn Game’, in: Cassidy, Simon and Eachus, Peter (2000), ‘Learning Style, Academic Belief Systems, Self-report Student Proficiency and Academic Achievement in Higher Education’, in: Educational Psychology, 20 (3), pp. 307–22

Friedman, Peggy and Alley, Robert (1984), ‘Learning/Teaching Styles: Applying the Principles’, in: Theory into Practice, 23 (1), pp. 77–81

Garavalia, Linda and Gredler, Margaret (2002), ‘Prior Achievement, Aptitude, and Use of Learning Strategies as Predictors of College Student Achievement’, in: College Student Journal, 36 (4), pp. 616–626

Gauss, Sandra (2002), Personality, Associated Learning Styles and Academic Performance of Third Year Psychology Students. Unpublished master’s thesis, University of Port Elizabeth, South Africa

Hao, De Yong, (2005), ‘Socialized Orientation and Cultivation of Qualified Manpower’, in: Educational Research, 304 (5), pp. 54–57

Huang, Hui Jing and Xin, Tao, (2007), ‘Linkage between Teacher’s Instructional Behavior in Classroom and Students Achievement’, in: Psychological Development and Education, (4), pp. 57–62

Hun, Tan Lay, Loy Chong, Kim and Milah, Ram (2013), ‘A Study on Predicting Undergraduates’ Improvement of Academic Performances Based on their Characteristics of Learning and Approaches at a Private Higher Educational Institution’ in: Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 93, pp. 1957–65

Huo, Jin Zhi, Cai, Yan, Zou Yan, Feng, Wei Juan, Zhu, Sheng Tao, Xu, Ping, Geng, Xiao Fang, Zhang Qun, Mao, Dan (1997), ‘Research on the interactive influence of motivation, intelligence and personality on academic performance’, in: Chinese Mental Health Journal, 11(6), pp. 328–330

Hyland, Ken (1993), ‘Culture and Learning: A Study of the Learning Style Preferences of Japanese Students’ in: Regional Learning Centre (RELC) Journal, 24, pp. 69–87

Isemonger, Ian and Sheppard, Chris (2007), ‘A Construct-Related Validity Study on a Korean Version of the Perceptual Learning Styles Preference Questionnaire’ in: Educational and Psychological Measurement, 67 (2), pp. 357–68

Jones, Cheryl, Reichard, Carla and Mokhtari, Kouider (2003), ‘Are Students’ Learning Styles Discipline Specific?’, in: Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 27, pp. 363–375

Joy, Simy and Kolb, David (2009), ‘Are there Cultural Differences in Learning Style?’, in: Inter-national Journal of Intercultural Relations, 33 (1), pp. 69–85

Kayes, Christopher (2005), ‘Internal Validity and Reliability of Kolb’s Learning Style Inventory Version 3 (1999)’ in: Journal of Business and Psychology, 20 (2), pp. 249–57

Kolb, David (1984), ‘Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development’, in: Kolb, Alice and Kolb, David (2005), ‘Learning Styles and Learning Spaces: Enhancing Experiential Learning in Higher Education’ in: Academy of Management Learning and Education, 4 (2), pp. 193–212

Kolb, David (1984), ‘Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development’ in: Thomas and Yunyan, Jia (2004), ‘Students’ Learning Styles and their Correlation with Performance in Architectural design Studio’ in: Design Studies, 26, pp. 19–34

Kolb, Alice and Kolb, David (2005), ‘Learning Styles and Learning Spaces: Enhancing Experiential Learning in Higher Education’ in: Academy of Management Learning and Education, 4 (2), pp. 193–212

Komarraju, Meera, Karau, Steven, Schmeck, Ronald and Avdic, Alen (2011), ‘The Big Five Personaltiy Traits, Learning Styles and Academic Achievement’ in: Personality and Individual Differences, 51, pp. 472–77

Kvan, Thomas and Yunyan, Jia (2004), ‘Students’ Learning Styles and their Correlation with Performance in Architectural design Studio’ in: Design Studies, 26, pp. 19–34

Li, Yan Xia and Lan, Xing (2013), ‘Research on the Event Human Resource Development Model from the Perspective of Cross-cultural Competence’, in: Modern Business Trade Industry, (19), pp. 103–105

Lian, Rong, Yang, Li Xian, and Wu, Lan Hua (2006), ‘A Study on the Professional Commitment and Learning Burnout of Undergraduates and their Relationship’, in: Psychological Science, 29 (1), pp. 47–51

Lu, Gen Shu (2005), ‘The Relationship between Learning Style and Academic Performance’, In: Higher Engineering Education Research, (4), pp. 44–47

Lynch, Thomas G, Woelfl, Nancy, Steele, David J, and Hanssen, Cindy A (1998), ‘Learning Style Influences Student Examination Performance’, in: The American Journal of Surgery, 176, July, pp. 62–66

Marton, Ferrence and Säljö, Roger (1976) ‘On Qualitative Differences in Learning: I – Outcome and Process’ in: Diseth, Åge and Martinsen, Øyvind (2003), ‘Approaches to Learning, Cognitive Style, and Motives as Predictors of Academic Achievement’, in: Educational Psychology, 23 (2), pp. 195–207

McFarland, (1997), cited in: Vawda, Aamena (2003), The Learning Styles of First Year University Students, Unpublished master’s thesis, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, South Africa

McSorley, Michelle (2002), The Construct Equivalence of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ) for a South African Context, Unpublished master’s thesis, University of Port Elizabeth, South Africa

Nie Jing, Zhao, Ming and Shan, Lin (2000), ‘Research on the Influence of Non-intellectual Factors on Academic Performance’, in: China Higher Medical Education, (2), pp. 47–50

Pan, Mao Yuan and Che, Ru Shan (2009), ‘Research on the Positioning and Feature of Provincial Universities and Colleges’, in: China Higher Education Research, (12), pp. 15–18.

Pedrosa de Jesus, Helena, Almeida, Patricia Albergaria, Teixeira-Dias, Jose Joaquim and Watts, Mike (2006), ‘Students’ Questions: Building a Bridge between Kolb’s Learning Styles and Approaches to Learning’, in: Education and Training, 48 (2/3), pp. 97–111

Peng, Xian, Ma, Su Hong, and Li, Xiu Ming (2006), ‘A Study on the Cognitive Styles and Gender Difference of Normal University Students’, in: China Journal of Health Psychology, 14 (3), pp. 299–301

Philbin, Marge, Meier, Elizabeth, Huffman, Sherri and Boverie, Patricia (1995), ‘A Survey of Gender and Learning Styles’ in: Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 32 (7/8), pp. 485–495.

Riordan, Melissa Clare (2002), A Preliminary Investigation into the Use of the Noncognitive Questionnaire (NCQ) with a Sample of University Applicants in South Africa. University of Port Elizabeth, South Africa. Online: http://books.google.co.za/books/about/A_Preliminary_Investigation_Into_the_Use.html?id=QLBRNwAACAAJ&redir_esc=y (accessed on 12 September 2014)

Robotham, David (1999), The Application of Learning Styles Theory in Higher Education Teaching, Visiting Lecturer in Human Resource Management, Wolverhampton Business School, University of Wolverhampton, United Kingdom

Rodrigues, Carl (2005), ‘Culture as a Determinant of the Importance Level Business Students Place on Ten Teaching/Learning Techniques: A Survey of University Students’ in: Journal of Management Development, 24 (7), pp. 608–21

Rosander, Pia and Bäckström, Martin, (2012), ‘The Unique Contribution of Learning Approaches to Academic Performance, After Controlling for IQ and Personality: Are there Gender Differences?’, in: Learning and Individual Differences, 22, pp. 820–26

Ruble, Thomas, L and Stout, David, E (1993), ‘Learning Styles and End-user Training: An Unwarrented leap of Faith’ in: MIS Quarterly, 17 (1), pp. 115–118

Schmeck, Ronald, Ribich, Fred and Ramanaiah, Nerella (1977), ‘Development of a Selfreport Inventory for Assessing Individual Differences in Learning Processes’ in: Komarraju, Meera, Karau, Steven, Schmeck, Ronald and Avdic, Alen (2011), ‘The Big Five Personaltiy Traits, Learning Styles and Academic Achievement’ in: Personality and Individual Differences, 51, pp. 472–77

Sun, Rui Jun, Shen, Ruo Meng and Guan, Liu Si (2012), ‘Research on the Factors that Influence University Students Learning Effectivity’, in: Journal of National Academy of Education Administration, (9), pp. 65–71

Tait, Hilary and Entwistle, Noel (1996), ‘Identifying Students at Risk through Ineffective Study Strategies’ in: Higher Education, 31 (1), pp. 97–116

The Chinese State Council (2010), ‘Outline of China’s National Plan for Medium and Longterm Education Reform and Development (2010–2010)’, Beijing?People’s Publishing House.

Tu, Chao Lian (2013), ‘Research on the Influence of Affective Factors on Academic Performance’, in: Journal of Xi’an International Studies University, 21 (3), pp. 62–65

Vawda, Aamena (2005), The Learning Styles of First Year University Students, Unpublished master’s thesis, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, South Africa

Vermunt, Jan (2005), ‘Relations between Student Learning Patterns and Personal and Contextual Factors and Academic Performance’ in: Higher Education, 49 (3), pp. 205–34

Wang, Jing Xin, Zhang, Kuo and Fu, Li Fei (2010), ‘Relationship between Professional Adaptability, Learning Burnout and Learning Strategies of College Students’, in: Studies of Psychology and Behavior, 8 (2), pp. 126–132

Wu, Yue (2004), Study on Relationship among Undergraduates’ Learning Strategy, Cognitive Style of FDI, Learning Style, Study Motivation and Learning Achievement, Unpublished master’s thesis, Shanxi Normal University, China

Xie, Jin Yu and Song, Guo Xue (2005), ‘An Analysis on the Students’ Possible Employment and their Useable Skills after Education’, in: Nankai Journal (Social Science), (2), pp. 85–92

Yin, Lei (2008), ‘A Research on the Relationship between Study Attitude and Study Achievement’, in: Psychological Science, 31 (6), pp. 1471–1473

Zhang, Zhi Hong and Geng, Lan Fang (2009), ‘A Positive Research on the Influence of University Students’ Learning Attitude on their Academic Performance’, in: Chinese University Teaching, (10), pp. 87–89

Zhang, Ti Qin, Liu, Jun, Yu, Hong Liang, Jiang, Yan, Xue, Jing (2009), ‘Research on graduate employment policy from the perspective of employability’, in: Economic Theory and Policy Studies, 2(6), pp. 70–86

Zhou, Ju Hong (2007), Effects of Gender, Culture, Personality and Belief about Language Learning, Unpublished master’s thesis, Xidian University, China