Step #4—Conduct Experiential Interviews

Employ Better Selection Methods to Improve Precision and Speed

Conventional interviews don’t work. Why? A job candidate is always on his best behavior. He tells you the right things and shares only the best parts of his background. Rather than painting a complete picture, a conventional interview narrows the lens, providing you with a mere glimpse of a person. This is why we’re often disappointed when the person we interviewed is not the one who shows up on Monday morning.

The problem with conventional interviews doesn’t stop there. During the interview, you’re selling the prospective hire on your company and culture. But no matter how many rounds in the process, conventional interviews don’t provide an accurate reflection of what it’s like to work at your company each day.

For an interview to be effective, it can’t be conceptual. Interviewing should be a reality check—a real and efficient experience that allows you and the candidate to make an informed decision. A decision based on facts. When armed with facts, each of us is capable of decisive action.

The Interview Experiment

My interviews weren’t always focused and fast. Like many people, I was told I should be slow to hire and quick to fire. My mentors in the late 1980s modeled long interviews packed with questions. Candidates making it out of round one went through more of the same in round two, with a third round added for really important hires. All in effort to get hiring right the first time.

Problem was, this slow approach was doing more harm than good. Work was piling up and good candidates were being lost to competitors. When hires were made, some worked out; many did not. Those that failed on the job had excelled during interviews. Our process was a crapshoot. Multiple rounds of exhaustive interviews were ending up with mixed results and exhausted managers. Less than half of the people hired lasted more than a year.

One day, out of sheer frustration, I decided to try something different. I’d been interviewing a candidate for a sales role. His background was impressive with almost a decade selling telecommunications equipment. Our phone screening went well; meeting him in person was the next stage.

Instead of putting him through our litany of questions during a face-to-face interview, I had him spend our entire time together selling. I introduced him to three people from other companies in our building. He had one task: Sell. All three buyers were open to considering new telecom products. If he didn’t land our sales job, his time was still well spent, giving him three opportunities to grow his current book of business.

In less than 90 minutes, I had my answer. He was not a fit for our job. The guy that showed up on the telephone was different from the salesperson I observed in action. He had great answers to questions in the phone screening, coming across as warm and affable. However, what he told me about his approach to selling and how he actually sold were different. In the three sales meetings, he was surly and pushy. Not the kind of person who would do well in our company.

Had I followed our process of multiple rounds of interviews, I would’ve had a conceptual experience. The candidate would have continued his tell, sell, and swell. I would’ve spent hours on someone who would’ve interviewed well but become a hiring disaster.

Instead, I’d invested less than two hours between the phone screening and a hands-on interview. I experienced the real person and saw and heard how he behaved when it counts—doing the work. The right decision, not to hire him, was clear and obvious. It was based upon factual evidence of how he performed as a salesperson versus the inaccurate picture he painted on the telephone.

The only question I had after the interview was how to apply this approach to different types of roles. It was relatively easy to let a salesperson sell and experience it being done. I had to develop ways to create real experiences that allowed me to see people in other jobs in action.

Experiential Interviews

I spent two years designing and testing “experiential,” or hands-on, interviewing. These interviews had to accomplish two things. First, they needed to determine if a candidate could do quality work. Second, they needed to show whether or not the candidate could work well with others.

I was picky about whom I’d meet, only interviewing someone if they matched the Hire-Right Profile. During an initial phone interview, I reviewed their abilities, communication skills, and personality-fit for our culture. A brief conversation determined who was worth bringing in for a hands-on interview.

The hands-on interview was divided into two parts. The first part was focused on having the candidate do sample work. Computer programmers were given specs, so they could write computer code. Accounting candidates analyzed financials. Marketing staffers designed a promotional campaign. Recruiters were provided sample jobs to fill. For each type of role, I developed tasks to be done based on real workplace situations.

During the second part, each candidate was joined by members of our staff. This gave me the opportunity to watch how they interacted with potential coworkers. I gave them a problem to solve or a question to answer as a team. Programmers had to work together to debug code that was crashing a system. Accounting candidates had to work with several members from the accounting department to trace errors in financial reports. Marketers participated in a brainstorming session on a marketing campaign. Recruiters had to collaborate with a hiring manager to plan the hiring process.

While all of this was happening, I was an observer. Joining me were several other leaders, each with a different hiring style. We quietly made notes of what we experienced. Debriefs after each hands-on interview allowed us to compare notes about how people matched up to our Hire-Right Profile. Reference checks were then used to affirm that the candidate had all of the Dealmakers and none of the Dealbreakers.

The results were groundbreaking. Interviews were shorter and more effective. We could see proof of whether or not candidates were good fits for a role and experience how they’d fit in. Our hands-on interview showed us how a candidate worked and interacted.

The leaders who had doubts about this new way of interviewing quickly bought in. As one put it, “Seeing is believing. Interviews have always seemed like a form of gambling. Sometimes I got lucky. Others times I did not. Being able to see someone in action makes this new form of interviewing far more accurate.”

Initially, I was concerned how candidates would be affected by having observers in the room. Would these people be a distraction? No. Candidates told us that after ten minutes they forgot the observers were there. The work kept their attention, allowing them to tune out the others.

Even the candidates themselves gave this new type of interview a thumbs-up. They got to experience the job and the team. Also, they liked how quickly they could determine whether the job was what they were looking for.

One of my biggest surprises was how experiential interviews engaged passive candidates (people not actively seeking a new job). Many passive candidates had previously balked at participating in a conventional interview. That was not the case when we allowed these candidates to “try out” a job. Passive candidates not only chose to participate, but often asked to join our company as soon as we could hire them.

After two years, the process was perfected. Hiring was a four-stage process: reviewing candidate documents, conducting brief phone interviews, one in-person hands-on interview, and reference checks. It no longer took weeks to hire one person. Now we could do it in a matter of hours. Most important, our new-hire success rate skyrocketed. Ninety-five percent of our new hires stayed for at least a year.

The Four Stages of Experiential Interviews

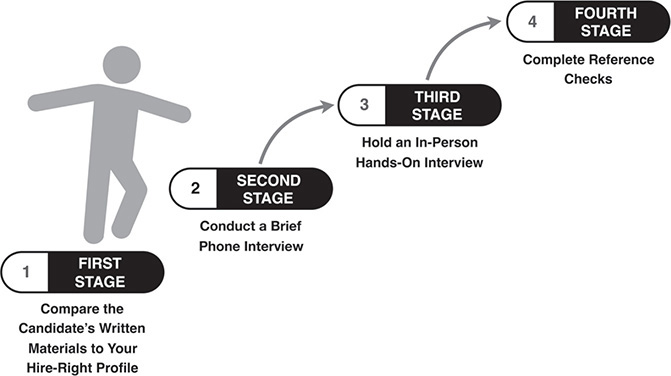

Today, thousands of companies across the globe engage in experiential interviewing. Regardless of industry, the process stages are completed in the same order (Figure 6.1).

FIGURE 6.1 The Four Stages of an Experiential Interview

Stage 1: Compare the Candidate’s Written Materials to Your Hire-Right Profile

You’ll compare each candidate to your Hire-Right Profile. To do this, you’ll use resumes or job applications plus, if needed, a few written questions. A candidate who has enough of the required skills, experience, and education listed under Dealmakers moves to Stage 2.

Stage 2: Conduct a Brief Phone Interview

A 20-minute (or less) phone conversation, for most roles, allows you to hear how the candidate communicates as you review their background and discuss the job. Also, this provides an opportunity to discover how their values, helpful behaviors, and personality features may or may not fit your company culture. If they match additional Dealmakers and have none of the Dealbreakers, they move to Stage 3.

Stage 3: Hold an In-Person Hands-On Interview

Here, you’ll have the candidate do sample work (both on their own and with others). The hiring team, comprised of the four hiring styles, observes silently. They “check off” any Dealmakers, Dealbreakers, Boosts, and Blocks. If they determine that the candidate has none of the Dealbreakers and most, if not all, of the Dealmakers, the candidate moves to Stage 4.

Stage 4: Complete Reference Checks

Reference checks (and background checks, if required for the role) are used to affirm that the candidate has all of the Dealmakers, none of the Dealbreakers, and few, if any, Blocks. If they pass this last stage, they’re offered a job immediately or the next time a seat opens.

A few additional notes:

• In Stage 3, I recommended that your candidate demonstrate their abilities by performing sample work. You also have the option to have them do real work; if you do so, however, you’ll have to pay them and comply with labor laws. These working interviews pay the going rate for doing key aspects of the job.

For example, a southeastern U.S. hospital asks nursing candidates who reach Stage 3 to work with patients directly. According to the hospital administrator, this has allowed the hospital to attract better nurses, who end up as long-term employees. “When we first floated this idea, our legal and risk management teams thought we were crazy,” the administrator said. “However, they got on board when we helped them understand that seeing a candidate in action actually lowered our risk. As a result, we now fill open jobs in less than an hour, and our patient outcome measures have improved significantly.”

• Candidates who don’t make it through the process are, whenever possible, referred to other employers. This goodwill gesture pays dividends, generating positive word-of-mouth advertising for your company.

The Flexibility of Experiential Interviews

Experiential interviews can be used for any type of role, yet the four stages remain the same. Each stage determines whether a candidate is a fit.

How do you apply experiential interviews to different industries and roles? Consider the following three examples.

Manufacturing

A midwestern U.S. manufacturer had ongoing problems in hiring machinists and welders. The company tried attracting candidates by improving its compensation plan. However, new hires didn’t stay long when another organization offered them more money. To remedy this problem, the manufacturer implemented experiential interviewing.

In Stage 1, the manufacturer asked each candidate to email them a resume and submit an answer to the following question: “Under what circumstances would you consider changing jobs?” The answer, along with the resume, allowed company leaders to see if a candidate had both the correct skills and mindset. They were looking for candidates with transferable experience and motives that went beyond money, such as opportunities for career advancement or ongoing skill development.

Candidates who reached Stage 2 were interviewed by a company machinist or welder over the phone. These conversations, lasting 15 to 20 minutes, covered a lot of ground. The interviewers gained insights about a candidate’s skills, behaviors, and personality. If a candidate had any of the Dealbreakers, Stage 2 is where they invariably showed up. When there were Dealbreakers, they’d end the process with that candidate.

Stage 3 was a joint hands-on interview: Two candidates were brought in simultaneously. They were given a single problem to solve together, such as fixing parts that been machined incorrectly. The interviewers watched how the pair interacted, noting how the candidates applied their skills, worked together, and solved the problem.

In Stage 4, the manufacturer checked references for candidates who passed Stage 3. As simple as this stage sounds, reference checks had always been a struggle. The reason: Previous employers would only confirm the most basic information, such as the individual’s dates of employment. For more meaningful detail, the manufacturer contacted the candidate’s former coworkers. These former colleagues were asked about the candidate, especially for experiences involving important Dealmakers and Dealbreakers. Their answers enabled hiring managers to gather the last bits of evidence needed for a fully informed hiring decision.

The experiential interviewing methodology eliminated candidates motivated by money alone. It also made it easier to attract passive candidates. In under a year, the company went from too few candidates to a surplus ready to accept a job the moment one opened. This success prompted the manufacturer to expand its use of experiential interviews in hiring engineers and managers.

Executives

A global recruitment firm struggled for years in hiring executives. Four of the previous six executives lasted less than a year. These failed hires fit a pattern: Their leadership style was excessively authoritarian. Rather than collaborating, they made demands and gave orders. Two of the four were also caught lying.

Ending this pattern of poor hires became the recruitment firm’s top priority. They began by creating Hire-Right Profiles that addressed the specific issues, adding Dealmakers, such as a collaborative leadership style, and Dealbreakers, such as lack of integrity.

During their next round of hiring, they experimented with experiential interviewing. In Stage 1, candidates were asked to provide a resume and answer written questions that delved into their leadership styles. Those who qualified for Stage 2 met by phone with several members of the hiring team. In addition to reviewing their background, the phone interview was used to discuss the pros and cons of collaboration.

The third stage was a hands-on strategy session with the candidate’s prospective team of direct reports. The candidate was given full control of this meeting. If she wanted to ask questions of the team or assign prep work before the session, she did. She set the agenda and ran the meeting. It was her show. How she led and what they accomplished were reviewed by the hiring team, some of whom were part of the exercise.

Reference checks rounded out the fourth stage of the process, confirming she met all of the required criteria, especially integrity. Reference checks included people at different seniority levels at the candidate’s previous employers. Each individual was asked for details of things they experienced, especially as they related to issues around integrity. Three potentially bad hires were averted as a result of details uncovered during this final stage.

Since implementation of experiential interviewing, the company has hired four executives, all of whom are still with the organization. The company’s board has deemed these individuals the “best hires ever made” as a result of the work each has accomplished so far.

Customer Support

A Pacific Rim software company took months to hire a single customer service manager. One of the reasons why had to do with the customer service manager’s daily work. Since helping customers took time, the software company felt a lengthy hiring process helpfully tested their candidates’ patience. Was this assumption correct? Did a drawn-out hiring process lead to successful hires? No. Less than 10 percent remained with the company more than two years.

Many of these hires, who were tenured and successful support professionals, weren’t coachable. They’d progress only as far as their current abilities took them. They’d get stuck, hitting a performance level below what was expected.

The software company replaced its drawn-out process with experiential interviewing. Hire-Right Profiles were created, adding “being coachable” as a Dealmaker. Telephone interviews zeroed in on examples of coachability. For instance, candidates were asked to share how they applied lessons learned from mistakes made in their current job.

The hands-on interview simulated some of the most challenging parts of the customer support job. Company employees played the role of “customer.” The task of the candidate was to solve the “problem” being presented by this customer.

Halfway through the hands-on interview the senior vice president of customer relations would pause the process and provide feedback to the candidate. Then, the hands-on interview would resume. Observers met afterwards to review their experience and discuss how coachable the candidate was during the interview. If candidates matched all of the Dealmakers, they moved to the final stage. References were used to affirm that he fully matched the entire Hire-Right Profile.

Candidates who passed all four stages were offered a job immediately, if one was open, or as soon as one became available. Those hired became exceptional employees. They ramped up quickly and broke company records. Tenure for all but a few progressed well beyond the two-year mark. Best of all, all four stages of the process took under one week to complete.

Creating Your Experiential Interviews

How do you carry out an effective experiential interview? I’ll walk you through the details.

Stage 1: Compare the Candidate’s Written Materials to Your Hire-Right Profile

With your Hire-Right Profile in hand, you’ll review a candidate’s background. You’ll look at their resume or job application. Also, you may choose to have them submit answers to written questions.

It’s important to remember that resumes and job applications are summaries. It’s rare that these summaries will allow you to determine whether someone matches your entire Hire-Right Profile. Instead, you’ll select Dealmakers and Dealbreakers to help you determine who moves to Stage 2. How many Dealmakers and Dealbreakers are enough? You’ll likely find that picking a few of each will suffice.

As an example, let’s look at how one company assessed candidates for a sales role. To pass Stage 1, the hiring team chose two Dealmakers and two Dealbreakers from the Hire-Right Profile:

Dealmakers

Healthy overachiever, demonstrated by exceeding expectations consistently

Follows directions

Dealbreakers

Sells price instead of value

Misses deadlines regularly

The company had candidates submit resumes. These candidates were also given a deadline to answer these questions:

• “Why do you fit this job? Please keep your answer to a few sentences.”

• “How do you sell? Be specific, but limit your response to two or three paragraphs.”

• “In your most recent role, what expectations were you asked to meet? How consistently did you meet those? What specific steps did you take?”

Candidates who failed to meet the deadline and follow directions were dropped. Those whose resumes and written answers passed the Dealmakers-and-Dealbreakers test moved on to Stage 2.

Stage 2: Conduct a Brief Phone Interview

Your Stage 2 phone interview should focus on whether a candidate meets your company’s needs and culture. You’ll also notice how the candidate speaks and listens, and you’ll get a sense of their personality. Your questions should lead them toward discussing topics important to your Hire-Right Profile.

One member of your hiring team should take the lead on the call. Other team members can listen in, helping to counteract hiring blindness. For staff level roles, a well-planned phone interview should take no more than 20 minutes. For executive jobs, plan on spending a maximum of 30 to 40 minutes.

Stage 3: Hold an In-Person Hands-On Interview

In Stage 3, you’ll want to watch the candidate do the type of work they’d be doing if hired. This can be a realistic simulation or work-for-compensation. During part of the hands-on interview, have the candidate work with others, such as one or more of the following: Potential colleagues, members of your hiring team, other job candidates.

Pick aspects that prove the candidate can do quality work. How do you choose? Have them demonstrate important skills. Role-play difficult conversations. Present them with problems they’ll need to solve.

An effective hands-on interview in Stage 3 can take as little as 60 minutes for staff positions. For senior and executive level roles, plan on up to two and a half hours.

Stage 4: Complete Reference Checks

Experiential interviewing is real, not conceptual. As a result, you’ll often find you’ve verified every detail on a Hire-Right Profile by the end of Stage 3. If so, you may be ready to hire the candidate now or the moment you have an open seat. In other cases, there may be one or more Dealmakers or Dealbreakers that remain unconfirmed. Regardless of which situation you find yourself in, it’s worth the investment to spend a few minutes on Stage 4. When you do, you’ll increase your new-hire success rate by at least 20 percent.

There are three keys to success when conducting reference checks:

1. Seek proof: Whether you’re questioning a reference giver about a candidate’s Dealmaker or Dealbreaker, ask for proof. Don’t stop at generalizations. Ask for a specific example.

2. Request that reference givers provide additional contacts: Smart candidates aren’t likely to connect us with people who are going to say negative things. Ask each reference giver for the names of people who worked with the candidate. Contact these people, asking them for the proof you seek.

3. Obtain at least one peer reference: References are traditionally conducted with managers. Yet, managers usually spend limited time with their employees day-to-day. Managers may also be restricted by company policy as to what they can share. Peers, on the other hand, spend more time with prospective hires and may not be confined by the same rules.

Always Interviewing, Occasionally Hiring

Hiring faster made sense to Troy and Claudia. They co-led a department in a pharmaceutical company that always had open seats. Both agreed they needed better hiring profiles and stronger candidate gravity, and that hiring teams would help counter hiring blindness. We worked together, in collaboration with their talent acquisition team, to improve these three parts of their process.

Agreeing on how to interview—that was a different matter. Claudia hated conventional interviews and felt they were the cause for the department’s failed hires. Troy, on the other hand, loved their process. Two phone interviews were followed by three separate face-to-face meetings. “We’ve crafted a great process. It includes behavioral interviewing and a ‘Topgrading’ assessment to spot top talent,” he said. “I’m not willing to give up on a process that isn’t broken. Our interviews work just fine.”

There was no convincing Troy to give experiential interviewing a try, even after Claudia “whiteboarded” their poor hiring statistics. “Half our good candidates drop out of our long hiring process,” said Claudia. “And, we’re not meeting our MBOs (management by objectives) for employee turnover this year. By any measure, our interviewing process isn’t just broken. It’s beyond repair.”

I’d been forewarned by their boss that Troy and Claudia were competitive. A hiring competition seemed like the right tool to help these two get unstuck from the status quo. Troy continued interviewing the old way; Claudia and I worked together to design and implement experiential interviewing. The rules of the contest were simple: Whoever filled the most jobs won. New hires had to pass their 90-day probationary period in order to count toward their hiring totals.

Who won? Claudia. It was a landslide. She hired four times as many people as Troy. He was stunned. “I figured she’d end up interviewing more people than I did,” he said. “But I thought I’d win in the end by making more quality hires. Many of the people she added to the team have ended up being better employees than those I brought on board. With less effort, she made more hires.”

The hiring contest had an added benefit: It filled all of the department’s open seats. Claudia and Troy joined forces and began cultivating talent before it was needed by always interviewing and occasionally hiring. They generated an ongoing flow of candidates, inviting those that looked like a fit for interviews. In a short time, they built an inventory of people who were ready to join the company when a job opened.

“One of my biggest surprises,” said Troy, “is how an active approach to hiring has made us a more attractive employer. We’re like a Broadway show that’s sold-out. The fact that it’s hard to get in creates buzz. Candidates keep asking about what makes us so special. Why do people line up ahead of time to land a job? Funny thing is, we’re the same company. The only thing we’ve changed is how we hire.”

Claudia’s mindset had also shifted. “Originally, I thought of hiring as an HR function,” she said. “Now, I realize the importance of my role. Interviewing candidates before the department has an opening ends up saving time. It also feels less pressured, since I’m not staring across the room at an empty desk.”

Always interviewing and occasionally hiring is an important goal in High Velocity Hiring. Once open seats are filled, hiring managers become active participants in lining up prospective employees before they’re needed. These potential new hires become part of the company’s Talent Inventory. In our next chapter, we’ll explore creating Talent Inventories in detail.