4

Creating Brown Shorts Answer Guidelines

Knowing how to ask insightful interview questions is a great skill. But knowing how to accurately evaluate the responses to those questions is an even better skill. Here’s what I mean. Consider the question “Can black hole evaporation be reconciled with quantum mechanics?” I know it’s a bit out there, but I’ve been told (by people who know) that it’s a great physics question. I would appear highly intelligent if I were to ask it of a bunch of physicists at a cocktail party. Unfortunately, I don’t know the answer (I’m not sure physicists do either), which limits my ability to evaluate and assess any responses. I’m not able to differentiate between a great answer, a plausible answer, and a terrible answer. And I might even get sucked into believing a completely implausible answer just because it’s delivered in an eloquent and confident manner. (Much like the impressive and convincing demeanor the majority of job candidates assume during an interview.)

I’m not saying that knowing the answer in advance is a prerequisite for every query you make. There are plenty of times when it’s perfectly OK to ask a question if you’re unsure, or even clueless, as to the answer. However, interviewing job candidates is when you definitely want guidelines on what good and bad answers sound like before you ask the question. This is a tool that you want to put in the hands of every member of your hiring team.

The concept of using Answer Guidelines as part of the hiring process is revolutionary in the world of hiring. In fact, Leadership IQ is the only group I know of that teaches this technique. You can find a lot of people who want to teach you how to create interview questions (albeit incorrectly). But there’s nobody else out there teaching how to create an answer key to those questions so you can accurately and consistently score the responses you get.

Let me share with you a recent experience with a Leadership IQ client that reinforces the need for Answer Guidelines. To give you some context, this was a large chemical company with lots of employees, many of them engineers. (I am being deliberately vague because I don’t want them identified.) Leadership IQ had been engaged to conduct a Brown Shorts project for this client. At the point when this story takes place, we’d completed the Discovery process and identified their Brown Shorts. We wrote a set of Brown Shorts Interview Questions and created custom Answer Guidelines to score the candidate responses to those questions. All these materials had been reviewed and approved by the organization’s executive team. So we were just entering the final phase of the project, the point where we go in and train all their hiring managers on how to implement these tools. (It’s all well and good to have great tools. However, if you don’t know how to use them …)

But before we started the formal training, I conducted a little experiment. As you’ll see, it’s an easy exercise. I encourage you to try it out with your own hiring team. First, I shared with the group the Brown Shorts Interview Question that had been developed during Discovery. “Could you tell me about a time when you didn’t know how to do something that a customer was asking you to do?”

Everybody loved the question. But despite the group’s enthusiasm for it, I felt certain that there were a number of different ideas floating around regarding what a good answer would sound like. I continued the exercise by asking the group to silently read an actual answer that had been documented during a recent interview. I didn’t want any second party vocal inflection or phrasing to influence individual thinking. And I asked all the managers to refrain from any discussion after they were done reading it.

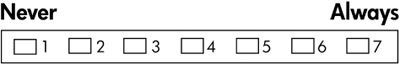

Then, based on what they had just read, I asked this group to rate the candidate with a view toward how well that person fit their organizational culture. They were instructed to use a numerical seven-point rating scale, where only the endpoints were labeled with 1 for “Poor Fit” and 7 for “Great Fit.” (See Figure 4.1.) There were no rating definitions given for points 2 through 6. I’ll explain why the rating scale was designed this way in Chapter 5.

Figure 4.1. The Seven-Point Scale

Just to review, here’s the Brown Shorts question again: “Could you tell me about a time when you didn’t know how to do something that a customer was asking you to do?” And here’s the answer that the candidate gave:

At my last job I was inundated with requests that were outside my area of expertise or influence. I am always pretty cautious when it comes to stepping outside my comfort zone, so most of the time I just turned the situation over to someone more experienced. After all, I want to make sure I’m protecting the company’s back because I don’t want to touch a project for which I’m unqualified and then have it do damage to the client. The client’s interests are always of paramount importance. And it’s critical that an engineer adhere to accepted practices and the proper processes. If I’m in a situation where I don’t know those processes, it’s better for me to pass the request to someone else that does.

The managers participating in this exercise struggled to rate this candidate. The final numbers showed something really interesting; the scores ranged from 1 to 7, with everything in between. In a room of 50 managers, every number on that seven-point scale was chosen by at least two people. And remember, these managers were all employed by the same company, they all shared similar professional backgrounds, and they all worked for the same group of executives. But despite all these similarities, their assessment of the candidate showed that my initial suspicion had been right—every person in that room had a wildly different idea about what a good (or bad) answer sounded like. And did they ever become animated when I shared that fact with them!

I overheard one discussion between two guys sitting at the same table. I was told that their offices are located next door to each other and that they’d been good friends for years. Their conversation went something like this:

Manager A: “What’s the matter with you? How could you score that answer a 6? This candidate would be a total failure here. He’s all wrong for us!”

Manager B: “Sure, that’s what you say. Because why would we want an engineer who actually followed a protocol!”

I asked the folks who gave the candidate a high score to tell me some of the things they liked about the answer:

• “This person is really focused on the customer. And you can tell extra care is being taken not to do anything that might damage our reputation with the customer.”

• “This is someone who appreciates the proper engineering mind-set.”

• “This sounds like someone who wants to protect the company.”

• “I would much rather see someone be cautious than reckless in this kind of situation.”

Then I asked the folks who skewered the candidate what they didn’t like:

• “We’re a company that always has to find solutions, no matter what; and this person just gives up the second something becomes what he or she considers too hard.”

• “I don’t like the ‘inundated with requests’ part. It makes me think that just about every request this person gets is going to be outside his or her comfort zone.”

• “I was really turned off by the admission of ‘I just turned the situation over to someone else.’ Also, there was zero mention of keeping the customer in the loop.”

• “I can handle the bringing in somebody else with more expertise part, but what bothers me is that I see no initiative to learn those new skills so that next time this person does know what to do and doesn’t have to rely on outside help.”

The results of this exercise highlight two big problems that organizations face when they Hire For Attitude without using Answer Guidelines. First off, you can usually find something you like, and something you dislike, in virtually every person you interview. (Of course, given that the consequences of hiring a bad attitude are worse than not hiring a good attitude, I’m more concerned about the former.) So without having some foundation to orient us and to tell us what good and bad answers sound like, it’s awfully hard to evaluate candidates consistently and correctly.

The second big problem is the extent to which everybody involved in your hiring process does (or does not) understand your Brown Shorts. It may seem absurd, but there are a lot of people in your organization, including leaders, who don’t know, or can’t articulate, what makes your culture special. Similarly, they can’t clearly tell you what separates your high and low performers.

This problem is not exclusively related to Brown Shorts. We conducted a study on whether employees understand their company’s strategy. Using data from Leadership IQ’s employee engagement survey, we assessed more than 70,000 employees on the extent to which they felt they could clearly articulate their organization’s goals for the year. Only 34 percent felt they could clearly articulate those goals. And it gets worse because next we took part of that 34 percent and asked them to go ahead and actually articulate the goals. According to the supervisors who graded their answers, only about half of them really knew the goals. This left us with only 17 percent of employees who could correctly articulate their organization’s goals. And while it’s possible that some people actually could articulate the goals but rated themselves low because they didn’t feel confident, my experience tells me that’s not a large percentage of employees.

How are you supposed to achieve a strategy when nobody on your team knows what that strategy is? It reminds me of the old joke: the bad news is we’re lost, but the good news is that we’re making great time.

Strategies, Brown Shorts, Mission Statements—they’re all susceptible to wrong interpretation. I recently gave a speech at a hospital’s leadership retreat about how to translate your strategy into the front lines. After I finished, the CEO was so pumped up by what I’d said that he pulled $1,000 cash out of his pocket and offered it to the first manager who could correctly write down the company Mission Statement. Guess how many were able to do it?

Out of the 150 leaders in the room, not one answered correctly. Nobody got the $1,000, and the really sad part is that the company’s Mission Statement is only 12 words long. As a reference, the Pledge of Allegiance contains 31 words. The real kicker, though, is that their Mission Statement is printed on the back of the name badge worn by every employee. But these folks were at an off-site retreat so they weren’t wearing their badges.

Too often we take our Brown Shorts for granted. “Well of course we know who we are,” we say, along with “and I can tell you exactly what differentiates our high and low performers.” But it’s always useful to see to what extent everybody agrees about that. If you went around the table at your next executive team meeting and asked each person to list the top three characteristics that differentiate high and low performers at your company, would each person have the same answer? What if you conducted this exercise at your next manager meeting? Or at an employee town hall?

The hiring managers at the chemical company where I conducted this exercise certainly didn’t use the same high and low performer characteristics to rate their candidate. But that inconsistency wasn’t because they weren’t living and breathing their Brown Shorts every single day. Rather, it was because they hadn’t yet learned to distill their Brown Shorts so they could explicitly say “These are the five characteristics that predict success or failure and that will let us measure every candidate accordingly.”

Two of the numerous Brown Shorts we identified during that chemical company’s Discovery stood out (and are especially appropriate for driving this all home).

• You take ownership of problems—even if you’re not the one who will ultimately fix it, you shepherd the process until it’s resolved.

• You’re a self-directed learner—you take full responsibility for growing and developing your skills, and while you may not learn everything, you’re in a constant state of growth.

Even if you lack any other knowledge about the organization, you now know that these two characteristics drive the success of its best people. You can easily assess the answer to a question such as “Tell me about a time when you didn’t know how to do something that a boss or customer was asking you to do.” And you can easily recognize that the sample answer I passed around that day clearly revealed that the candidate in question was a poor cultural fit. There just wasn’t much ownership, self-directed learning, or desire for personal growth in that answer.

Hiring for Attitude requires both your Brown Shorts and your Brown Shorts Interview Questions. But in order to make it all work, you also need your Brown Shorts Answer Guidelines. That way, when you (and every member of your hiring team) are in the middle of a live interview, you’ll know exactly what you should be listening for and how you should react when you hear it.

Let’s get started creating your Answer Guidelines.

BROWN SHORTS ANSWER GUIDELINES

So exactly what are Brown Shorts Answer Guidelines? They are really quite simple and contained in one document. That written document considers, one-by-one, each of your Brown Shorts Interview Questions. After each question comes a list of good answers (called Positive Signals) and a list of bad answers (called Warning Signs). There’s also a scoring form, which we’ll address in Chapter 5.

Before we dive into how to formulate your questions, here’s an abbreviated version of one organization’s Brown Shorts Answer Guidelines. This will allow you to become familiar with the basic format you’re going to use in creating your own answer guidelines.

Brown Shorts Interview Question

Tell me about a time when you didn’t know how to do

something that a boss or customer was asking you to do.

Warning signs: These types of answers can indicate a poor fit with the organization’s culture.

• “When I don’t know how to do something I just placate the requestor and obfuscate the issue until hopefully it starts to go away. I’ve found it to be pretty common for a customer or boss who gets all hot and bothered over an issue to completely forget it within 72 hours.”

• “I had one boss who was terrible at communication, and a lot of times it negatively affected the procedures and work flow in our department. I know it really impacted my work and made my life pretty miserable. There were a lot of times when I didn’t find out about process changes until after the fact. This slowed me up a lot, and I spent many days just frozen, unable to do anything, because I literally didn’t know what to do.”

• “I have yet to encounter a situation that presents me with any real challenge regarding execution. I simply don’t allow myself to make mistakes.”

• “I was scared I might fail, so I told everyone that I was going to fail so I wouldn’t look like a fool if I did. But in the end it all worked out OK.”

• “That describes every day at my last job. Things were constantly changing, and there was just no way to keep up with it all. What a mess. And when you consider that my manager was offering zero support and guidance, well, it’s easy to understand why I had absolutely no idea what to do.”

Positive signals: These types of answers can indicate a good fit with the organization’s culture.

• “It really helps to have a close group of peers with whom you can discuss opportunities and share ideas. I actually initiated a forum of really talented people from all over the organization at my last job. I set it up so we met once a week to discuss our challenges and problems. It was a great way to get feedback and advice, especially when I wasn’t sure how to do something.”

• “I ask lots of questions, and if possible, I spread my queries out among many different people. Not only does this ensure I’m not a burden on any one person, it also allows me to get a lot of different perspectives.”

• “I was honest with the customer and explained that I wasn’t familiar with what he was looking for, but that I would connect him with the person in our company who was the expert on this. I made this connection within the 24-hour window I had promised to the customer, and I kept in touch with both the customer and our expert throughout the process. Then I went and learned as much about the issue as I could so next time I would be prepared.”

• “A client said she simply couldn’t wait for my solution, and that even though her company managers preferred to work with me, they had to go with a competitor who could offer an immediate solution. Up until then we’d been talking on the phone, so while I told her I understood, I asked if I could visit with them in person that afternoon to maybe gain a new perspective on the situation. After a review of their system that took less than an hour, I was able to find a solution, and the customer went with us.”

• “I thought that the problem might be far more complex than the person making the request realized. So I called a team meeting to review the situation and to brainstorm how we might fix it. The feedback was great, and I left the meeting knowing exactly what to do. I used to think it took too long, and was too arduous a process, to bring everybody together like that. But I now realize the value of putting time in at the front of problem solving. It’s much more productive than getting everyone together after the fact to clean up a mess that resulted from a hasty and poorly made decision.”

Again, this is just an abbreviated example. Your list of Warning Signs and Positive Signals could be a page or more in length each. But this example demonstrates that the Positive Signals show what good answers sound like and Warning Signs represent what bad answers sound like. Too often interviewers let something slide, miss a key signal, or just misinterpret the answer. Your Answer Guidelines are designed to show exactly what good and bad answers sound like, so when you or your hiring managers hear either one, you can identify it immediately.

WHY DO WE USE ACTUAL ANSWERS?

While Leadership IQ is the only group I know of that has developed a formalized approach to creating Answer Guidelines, every once in awhile I do see somebody else attempt to assemble an interview question answer key. But instead of giving examples of actual answers, they give general admonitions such as “Look for answers that indicate adherence to ethical standards” or “Beware of answers that indicate a passive acceptance of accountability but no proactive assumption of accountability.”

There’s nothing inherently terrible about these guidelines, but they are pretty abstract, and that alone renders them woefully inadequate as teaching tools. I’m sure I’m not the only one who finds it challenging to learn in the abstract. For instance, say you were trying to teach me how to make a candidate more relaxed in an interview in order to get him to loosen up and drop his guard. You could tell me “Arrange the seating in the interview room so it puts the candidate at ease.”

That advice is fine as long as my vision of what that looks like is similar to yours (and it probably isn’t). Instead you want to say something less abstract, perhaps “Never sit across the desk from the candidate because that creates a barrier. Get out from behind the desk and arrange the chairs so they face each other. Then turn the chairs about 20 degrees away from each other. That will create a much more open and comfortable space, but it eliminates any chance of your knees hitting his.”

The latter instruction is a lot more explicit and far more actionable. Similarly, when you use clips of actual answers in your Brown Shorts Answer Guidelines, it’s a lot easier for folks to learn what good and bad answers sound like. You’re not leaving anything open to misinterpretation as you do when you provide an abstract explanation.

Of course, a lot of the real candidate answers that your Brown Shorts questions elicit are going to be long-winded and contain irrelevant details. Also, the responses will vary wildly from candidate to candidate, and you can’t plan for every possible permutation. But the snippets that appear in your Answer Guidelines don’t need to contain or cover everything that could ever be said. You just need to represent the hallmarks (Positive Signals and Warning Signs) of the good and bad answers so both can be identified quickly and accurately while you’re listening to all those specific situational details. The Answer Guidelines ensure that you can accurately assess the content of the answers. Factors such as the length and specificity of a candidate’s answers can be assessed independently.

Take a minute and carefully re-read the example list of Warning Signs and Positive Signals. Now that you’ve got a better understanding of how it all works, you should be able to pick out the defining characteristics of that organization’s high and low performers. These Brown Shorts qualities are intimated everywhere in the snippets I shared.

MARK’S ASSESSMENT OF THE ANSWER GUIDELINES

At some point during our projects (at least the ones I’m personally involved with), I like to read through the client’s Brown Shorts Answer Guidelines as though I were part of the culture and not an independent observer. It gives me a chance to react as their managers will likely react and anticipate how they’ll feel when reading the Guidelines.

Following are some of my initial reactions to the sample set of Brown Shorts Answer Guidelines; I approached my review as though I were an executive at that chemical company. And based on what I know about this company (their culture), my comments reflect the thoughts that went through my head immediately after hearing that snippet of answer. Perhaps I got a little snarky or sarcastic, but I wanted to give you my relatively unfiltered perspective.

Remember that two of the Brown Shorts for this company were:

• You take ownership of problems—even if you’re not the one who will ultimately fix it, you shepherd the process until it’s resolved.

• You’re a self-directed learner—you take full responsibility for growing and developing your skills, and while you may not learn everything, you’re in a constant state of growth.

Here are my thoughts.

Warning Signs

These types of answers can indicate a poor fit with the organization’s culture.

• “When you don’t know how to do something you just placate the requestor and obfuscate the issue until hopefully it starts to go away. I’ve found it to be pretty common for a customer or boss who gets all hot and bothered over an issue to completely forget it within 72 hours.”

Mark’s comment: I’m sure glad my doctor doesn’t talk like this. I guess you’d have to be writhing in pain for more than 72 hours before this person would finally decide to take ownership of your problem. This is major denial and the opposite of true accountability.

• “I had one boss who was terrible at communication, and a lot of times it negatively affected the procedures and work flow in our department. I know it really impacted my work and made my life pretty miserable. There were a lot of times when I didn’t find out about process changes until after the fact. This slowed me up a lot, and I spent many days just frozen, unable to do anything, because I literally didn’t know what to do.”

Mark’s comment: I’m concerned here about the way this person was “frozen” by a lack of clarity. First, everyone is going to suffer some poor communication, but does that mean we all freeze up because of it? Or do we actively seek out whatever information we can find and take some positive steps forward (as our Brown Shorts say we do)? Second, I’m concerned about the speed with which this person dumps all the responsibility for poor communication on the boss—again, not much ownership of the problem.

• “I have yet to encounter a situation that presents me with any real challenge regarding execution. I simply don’t allow myself to make mistakes.”

Mark’s comment: Show me somebody who’s never made a mistake and I’ll show you somebody who’s never had a job. How can you be a self-directed learner without a little humility that says “there are things I still need to learn?”

• “I was scared I might fail, so I told everyone that I was going to fail so I wouldn’t look like a fool if I did. But in the end it all worked out OK.”

Mark’s comment: There is a fine line between self-deprecation (which can be endearing) and a lack of self-esteem (which is not). As noted in our Brown Shorts, I don’t want people who are preparing to fail. I want people who take ownership for ensuring that things do not fail and who learn the necessary skills to guarantee that outcome.

• “That describes every day at my last job. Things were constantly changing, and there was just no way to keep up with it all. What a mess. And when you consider that my manager was offering zero support and guidance, well, it’s easy to understand why I had absolutely no idea what to do.”

Mark’s comment: If this person was presented with opportunities for self-directed learning every day at his last job, and he described that situation as a “mess,” it’s pretty easy to see he isn’t going to fit into our Brown Shorts. Plus, isn’t it reasonable to think that after the first few hundred times you were asked to do something you didn’t know how to do, that maybe, just maybe, you’d start to learn how to do a few of those things and solve the problem?

Positive Signals

These types of answers can indicate a good fit with the organization’s culture.

• “It really helps to have a close group of peers with whom you can discuss opportunities and share ideas. I actually initiated a forum of really talented people from all over the organization at my last job. I set it up so we met once a week to discuss our challenges and problems. It was a great way to get feedback and advice, especially when I wasn’t sure how to do something.”

Mark’s comment: This person took ownership of creating her own system for self-directed learning. That pretty much exemplifies our Brown Shorts.

• “I ask lots of questions, and if possible, I spread my queries out among many different people. Not only does this ensure I’m not a burden on any one person, it also allows me to get a lot of different perspectives.”

Mark’s comment: This shows ownership and learning, all in one sentence.

• “I was honest with the customer and explained that I wasn’t familiar with what he was looking for, but that I would connect him with the person in our company who was the expert on this. I made this connection within the 24-hour window I had promised to the customer, and I kept in touch with both the customer and our expert throughout the process. Then I went and learned as much about the issue as I could so next time I would be prepared.”

Mark’s comment: This person took ownership for finding the customer a solution, even if he wasn’t the one providing it. There is also a clear sign of ownership for making sure the customer was well served throughout the process. And then to put the cherry on top, he learned about the issue so that next time he’d be able to solve the issue by himself.

• “A client said she simply couldn’t wait for my solution, and that even though her company managers preferred to work with me, they had to go with a competitor who could offer an immediate solution. Up until then we’d been talking on the phone, so while I told her I understood, I asked if I could visit with them in person that afternoon to maybe gain a new perspective on the situation. After a review of their system that took less than an hour, I was able to find a solution, and the customer went with us.”

Mark’s comment: It’s amazing how taking ownership of a customer problem often leads to getting a lot more business from that customer. This person didn’t get angry and tell the customer where to stick her account. The customer’s needs were put first, but then, by taking full ownership of the problem, he didn’t just let it go. He went back in to the customer, figured out the underlying issue, and won the account back.

• “I thought that the problem might be far more complex than the person making the request realized. So I called a team meeting to review the situation and to brainstorm how we might fix it. The feedback was great, and I left the meeting knowing exactly what to do. I used to think it took too long, and was too arduous a process, to bring everybody together like that. But I now realize the value of putting time in at the front of problem solving. It’s much more productive than getting everyone together after the fact to clean up a mess that resulted from a hasty and poorly made decision.”

Mark’s comment: Self-directed learning doesn’t just have to be specific knowledge or skills; it can also be knowledge about how to solve problems. And that’s the growth that this person shows in her answer.

The Answer Guidelines bring your Brown Shorts to life. I said this before, but it bears repeating—learning things in the abstract is hard. I see many different companies that instruct their hiring managers and HR departments to look for people with integrity, positive attitude, influence, innovation, proactivity, achievement, and all the rest. But what do those things sound like when they are coming at me during an interview? Yes, I want proactive, positive people with integrity. But how do I know when I’m interviewing someone like that? How do I tell if this person, or that person, really has all those characteristics? Remember what I said in Chapter 1 about the need for Behavioral Specificity? The Answer Guidelines are all about Behavioral Specificity. If you don’t bring your Brown Shorts to life with examples of actual answers, it may be impossible to accurately evaluate the people you interview.

Here’s a nonworkplace example of what I mean. If my wife sends me to the store to buy new sheets and she says, “Get something that matches our bedroom,” I’m dead. I think gold silk sheets would look good—you know, the kind that when I lie on them make me look like a Roman Emperor waiting to be fed grapes. So the instructions “Get something that matches …” is not nearly specific enough for me to meet my wife’s expectations. I am going to need a more fleshed-out example, something like “The best colors to match our bedroom would be medium or dark shades of brown. No pastels and no white. Make sure they are pure organic cotton, and don’t even look at anything that has a thread count of 300 or lower—400 and up is best. They should feel like cool silk to the touch, but whatever you do, don’t get real silk (my wife knows me a little too well). Really busy patterns aren’t going to work, and floral is out, so look for something uncomplicated, geometric, but still flowing, you know, like the Picasso you love so much at MoMA.” Now these guidelines give me a good understanding of exactly what’s good and what’s bad. I’m going to be able to recognize the perfect sheets the second I lay eyes on them.

One final note before we move into the execution phase of your Answer Guidelines. Just by looking over the sample guideline shown previously, you can see that your hiring managers will need to familiarize themselves with the content in there. Don’t worry—this doesn’t take long. In fact, most people need to read through the guidelines only a few times to understand them completely. But your managers will need to practice using the guidelines in order to make the most efficient use of them. Remember the exercise at the beginning of this chapter where a group of managers couldn’t agree on how to rate the answer I showed them? Well, after teaching the Answer Guidelines, we did a few more exercises like that. And the second time those managers rated the answers all within 1 point of each other, with most scores landing squarely on the same number. That’s hiring consistency.

WHERE DO ANSWER GUIDELINES COME FROM?

Now that you have a feel for what Brown Shorts Answer Guidelines look like and how they work, I assume you’re thinking “Sure, we can show pages of actual answer examples, but where do they come from?” Here’s the answer, and it may surprise you a bit. Those answer examples, both good and bad, come from your current employees. That’s right; those Positive Signals are your high performers being high performers. And those Warning Signs are coming straight from the minds of your lower performers.

I’ve yet to see an executive receive his Brown Shorts Answer Guidelines and not get at least a little wind knocked out of him. I’ve even heard a few respond with a comment like “Umm, these are our people—saying these things—that run totally counter to our Brown Shorts? How did this happen?” Of course, we know how it happened, but now we need to focus on moving forward.

So how are you supposed to get those unfiltered responses from your employees? The answer is, you ask. You ask cleverly, but basically, you ask. Here’s the approach we take at Leadership IQ when an organization brings us in on a Brown Shorts project. First we discover the organization’s Brown Shorts and then use that insight to craft its Brown Shorts Interview Questions. We then make a few strategic tweaks to the questions, after which we put them into an online survey. Finally, we send that survey to the organization’s employees. Note that we typically use a carefully selected sample of employees, and we use a statistical method called a power study to determine how many respondents we’ll need for the survey.

But even if you don’t have access to these kinds of tools and resources, you can still conduct an effective employee survey to give you the information you need. In fact, your Brown Shorts Interview Questions are so powerful that you’ll get some amazingly honest answers even if you don’t make the tweaks. (I’ll share more on what the tweaks are, and why you may want to consider making them, in just a bit.) Leadership IQ performs many employee surveys every year. As a result, we’ve collected piles of data on why some surveys generate better responses than others. One critical factor we’ve found relates to how the survey is framed. You don’t want to just blast out a survey with five interview questions and ask people to respond. All that will do is make your current employees feel like they’re re-interviewing for their jobs—not an effective use of anyone’s time. (You have performance management systems to determine if someone should remain in a job.) Instead, you want employees to feel like they’re helping the organization define and establish its standards (which they are).

Companies choose to work with an outside firm like Leadership IQ because when sensitive questions are asked, people feel more comfortable talking to an independent professional. (It’s kind of the same as people telling their life stories to a bartender they’ve never met before.) It’s confidential, it’s secure, and there’s no lingering weirdness after the conversation or fear that something they said will be used against them down the line. And, frankly, it’s nice to have an outside perspective, because your company managers may not always be able to see what’s right in front of them. We saw this example in the chemical company that did the question rating exercise at the start of this chapter. Even though those managers were living and breathing their Brown Shorts every day, they still struggled to articulate them clearly.

Let’s look at this another way. I’ve lost 40 pounds in the past few years. Yet, when I look in the mirror, I still see pretty much the same body. That’s because I look in the mirror every day, which makes it difficult to visually track the gradual physical changes that happen during weight loss. It’s not until I take out some old pictures that I can see differences. My age now starts with the number 4, and yet, aside from the much more obvious gray streak in my hair, I don’t think I look much older than when my age started with the number 2. OK, perhaps I’m delusional, but aren’t we all? Just a little bit?

Whether it’s our bodies or our organizational culture, surveying ourselves objectively is a challenge. And that’s why outside groups like Leadership IQ can usually get more thorough results, especially with surveys that ask about sensitive topics. But again, you can certainly conduct this survey yourself and get the results you need. You just have to frame the survey properly.

WHAT’S IN THE SURVEY?

There are four steps to framing an effective survey. You need all four pieces, and they need to be executed in the following order.

Framing a Survey Step Number 1: An Invitation to Participate

First, invite people to participate in the survey. An invitation helps plant the seed that by completing the survey they’re choosing to help the organization. You will lose the warm and fuzzy edge if you make the survey sound mandatory. Be sure to provide a few background details (keep it short), and to give simple instructions—you don’t want to make this complicated and turn people off from participating.

Following are three actual e-mails sent by senior executives inviting their employees to participate in a Brown Shorts Answer Guidelines survey. They are all great models to emulate.

Example 1: We have asked an outside firm, Leadership IQ, to help us understand how to better interview and hire people that more closely match our unique culture. They have started their work with a first stage of discussion, and are on to the next stage. This is where we would like your help. Please take just a few minutes to complete the short and important survey at the link below and give them your thoughts. You will find it interesting, and I appreciate your support of our desire to learn how to do an even better job of “growing our team together.” Please take time to give us your feedback before Monday, June 1st.

Example 2: I need your help. As you know, we’re growing fast as a company, and it’s time to grow our team to match. We’ve got a great recipe for success right now, and I want to make sure that every new hire we bring on board is a great fit for our culture. And who better to ask for help with that than the folks who embody that culture? With the contribution of just a few moments of your time to answer the five survey questions attached, you’ll be making an impact on whom and how we hire. Don’t worry about making it pretty or grammatically perfect. I’m far more interested in hearing your candid thoughts. Please email me your completed surveys by the end of the week.

Example 3: ACME Corp. has asked survey firm Leadership IQ to help research the attitudes and characteristics that make our organization so successful. And because you exemplify those successful characteristics, Leadership IQ is asking for your insights. The attached survey consists of six open-ended research questions. Please answer them based on your own beliefs and experiences. We want to know what you think about the characteristics that make people successful in this organization. And we also want to know about some situations in which you’ve personally evidenced those successful characteristics.

Framing a Survey Step Number 2: Warm-Up Questions

Begin the survey with a few easy questions about the characteristics that exemplify success and failure at your organization. These warm-up questions serve two purposes. First, they loosen people up and let them feel more fluid and competent about taking the survey. You never want the first question in a survey to feel like a hit to the head with a two-by-four; you want to ease people into the process. Second, these warm-up questions validate your Brown Shorts Discovery. The employee responses will confirm whether or not you really nailed down those Brown Shorts high and low performer characteristics.

Your warm-up questions might sound something like this:

• Please list three to five attitudes or personality traits that you think describe the most successful people at Company X.

• Please list three to five attitudes or personality traits that you think describe the least successful people at Company X.

Framing a Survey Step Number 3: Introduce Your Brown Shorts Questions

Once people are warmed up and feeling ready to share, you can introduce your Brown Shorts Interview Questions. As I’ve said, it’s absolutely fine to go ahead and use them exactly as written, the same way you will in your interviews. But because you’re not going to have the luxury of any follow-up or probing questions, it’s a good idea to make a few tweaks to compensate for that. The goal is to gather as many real-life situations as possible, so consider each question and how you might, with a small tweak, better achieve that objective.

For example, say one of your Brown Shorts questions is “Could you tell me about the most difficult customer you dealt with?” Unlike in an interview, the survey is not intended to assess how forthcoming the person on the other end of this question will be about providing details that reveal attitude (why I earlier told you to delete your leading questions). In the survey, you want to make sure you get those details. So you might tweak your question to sound more like “Could you tell me about the two most difficult customers you dealt with?” By adding in the “two” you’ll probably get at least two somewhat detailed descriptions of situations that involved difficult customers. This maximizes the time you’ve got with your respondents, and it ensures that you’re going to get the information you need.

We always make a second important tweak. In addition to asking about personal examples, we also ask survey participants to describe what they’ve seen others do in these situations. For example, consider the Brown Shorts question “Could you tell me about the two most difficult customers you dealt with?” Here, instead of just asking about their individual experiences with difficult customers, you might also ask them to describe any situations they may have observed where a peer struggled to deal with a difficult customer.

Note here that bringing in the “other party” option is a great way to make people feel safe to share. When you were a teenager, did you ever want to ask your parents something really important but, because it was a sensitive topic, you were afraid how they would react? If you ever faced that situation, then you probably began your question with “I have a friend … (who was offered drugs, who saw someone cheating, or who whatever).” It’s the biggest parenting joke around because we all know who the “friend” really is. But it’s a useful device because it allows the teenager to raise sensitive topics that might otherwise have remained unspoken.

The same rule applies here when we ask employees to describe situations in which their colleagues have struggled or faced difficult customers. It allows us to assess the extent to which their personal answers have the same intensity and directionality as the answers about their colleagues. And thus we can more accurately evaluate their responses and build better scoring ranges.

Framing a Survey Step Number 4: Analyze

The final step involves analyzing these dozens, or hundreds, or thousands, of survey responses. All you’ve done so far is gather data; you haven’t actually built any Answer Guidelines. So now you’ve got to code and analyze every survey response, grade it, identify whether it represents a positive or negative example, and rate the degree to which it’s positive or negative. Once that’s all accomplished, you can select the best snippets for examples to use in your Brown Shorts Answer Guidelines. At Leadership IQ we also subject all the responses to some pretty advanced textual analysis (some of which I’ll share in the next chapter) that identifies the specific themes in the responses, as well as various types of language uses, grammar, verb tenses, emotional language, and much more.

Implementing the survey may get a bit technical, but the underlying idea is quite simple: you’re testing your Brown Shorts Interview Questions and asking employees to tell you what good and bad answers sound like. If you do that, you’ll have great questions, and you’ll know how to identify the great (and not great) answers. You’ll significantly increase the odds of picking out the future high performers and avoiding the low performers.

For free downloadable resources including the latest research, discussion guides, and forms please visit www.leadershipiq.com/hiring.