On October 15, 1981, in the stands of the sold-out Oakland Coliseum, Krazy George Henderson had a vision. It was the third game of the American League play-off series between the Oakland Athletics and the New York Yankees, and the A's had lost the first two. Krazy George was a professional cheerleader, in the A's employ for three years or so. No pom-pom shaking college rah-rah, George roved solo up and down the aisles of the stadium clad in cutoff shorts and a sweatshirt, a manic Robin Williams character with Albert Einstein hair, banging with abandon a small drum, inveigling the crowd, and leading cheers with an infectious intensity that had endeared him to fans throughout the Bay Area. Most shouts were familiar, like "Here we go, Oakland, here we go!" But this day was different. On this day, Krazy George imagined a gesture that would start in his section and sweep successively through the crowd in a giant, continuous wave of connected enthusiasm, a transformative event that later proved historical. October 15, 1981, is the day Krazy George Henderson invented the Wave.[1]

Everything has to start somewhere.

I had long been fascinated by the Wave, so I wanted to find Krazy George and ask him about the story of that first Wave. "The day I started it, I already knew what I wanted," he told me. "I knew what was gonna happen, but nobody else in the stadium did.

"First thing, I hit my drum. That focuses everybody within three to four sections of me. It's the secret to why I am successful. See, the drum shows energy and emotions; it shows I am personally involved with the fans. I move everywhere in the stadium (I am constantly moving), and I pound the drum. They see me sweating, they see the energy, they see that I love the game, and that I love the team. I act like a fan wants to act, and it releases something in them.

"So that day, I had to tell them what I envisioned. It's so important to set the cheer up. If everybody doesn't do it, it won't go. You have to have almost total participation for it to go, and that's the point. I pounded the drum and I started screaming, 'Here is what we're gonna do. We're gonna stand up and throw our hands in the air. I want to start with this section, and we're gonna go to this section,' and I yelled down to the next section. 'I'm gonna start it and it's gonna keep going.'

"I knew it would die. I didn't know how far it would go before it died, but I knew it would. No one had ever seen this before. So, I prepared them. I told them that when this thing died, I wanted all three sections to boo as loudly as they could. I couldn't reach out to the whole stadium myself, but I thought as a group we might. Then I said, 'We're gonna start on three, this section first; then you are gonna go, and get ready down there.' I yelled as loud as I could, and I knew what was gonna happen, and I started it, and the first section stood and threw their hands in the air ... then the second section ... the third ... the fourth; it went about five sections and it just tailed off to nothing. People were looking at the game and they didn't know what was happening. So it died.

"Right on cue, three sections just went 'Booo!' and I pounded my drum. I was screaming and waving my arms. They can't hear me across the field, but they can hear my drum. They saw me flailing my arms and shaking my drumstick at them, and they got the idea. So, I started it a second time and it went about 11 sections—about a third of the way around—and it died behind home plate. Suddenly, the hugest 'Booooo!' you ever heard, maybe six, eight sections, came out. But it focused everybody, and they figured out what I wanted to do. So I said, 'We're gonna try it again.' I didn't say 'try'; I said, 'We're doing it again,' and I started it the third time.

"By the time I looked around, all three decks in the stadium were doing it, all in unison, throwing up their hands, a giant wave of human energy going around the stadium. It swept behind home plate. It kept going, and it got stronger and stronger. The people were screaming and yelling. It came around, went behind home plate and then all the way through the outfield, through the bleachers, and back to our section, and it just kept going. It swept right back, and it got even more powerful. Everybody was going crazy. Nobody had ever seen this before.

"The great left fielder for the A's, Rickey Henderson, known as 'The Man of Steal' for his prowess running the bases, was coming up to bat at the time. He looked up and saw this thing going around and around the stadium, and he stepped out of the batter's box and adjusted his gloves for about two minutes, watching this thing. He just stood there, looking at this thing, adjusting his batting gloves. I don't know how many times it went around—four, five, six times—it was that powerful.

"After the Wave, the crowd was noticeably different, hyped up and involved in the game. They knew they'd helped out. They felt the energy. When I did the next cheer, the defense cheer or the clapping, it was much louder. That's the thing I saw that day, and still see today after almost 25 years of leading the Wave, the added energy that it brings to the stadium or the arena or whatever venue I'm at. The fans start feeling that they are part of the game and they're adding to it."

The Wave is an extraordinary act. All those people, spread out over a vast stadium, with limited ability to connect or communicate, somehow come together in a giant cooperative act inspired by a common goal: to help the home team win. It defies language and culture, occurring with regularity throughout the world at Tower of Babel events as diverse as the Olympics and international soccer games (in fact, it's often called the Mexican Wave or La Olá because of its first appearance on the international stage at the Mexico City World Cup Finals in 1986).[2] It transverses gender, income, and societal status. It is a pure expression of collective passion released.

When I started LRN Corporation in 1994, I thought it would be extraordinary if I could capture in the workplace something of the spirit of the Wave—that rich, cacophonous tapestry of human beings coming together to create that home court advantage. Was there some way to foment that kind of creative energy focused on our business goals? What does it take to start a Wave?

If you consider the Wave as a process of human endeavor, you realize immediately that anyone can start one—an enthusiastic soccer mom, four drunken guys with jellyroll bellies and their bare chests painted Oakland green, or eight adolescents who idolize the team's star player. You don't have to be the owner of the stadium, the richest or most powerful person there, or even a paid professional like Krazy George. No one takes out their business card and says, "My title is the biggest; let the Wave start with me." Anyone can start a Wave; it is a truly democratic act.

So, how do you do it? Let's have some fun for a minute and break it down. Say, for instance, that you are sitting in the stands at a football game and the home team is down by a touchdown. You see your team huffing and puffing, and you are disappointed that your fellow fans seem lethargic and complacent. Suddenly, you have a vision, a vision to help your team win, to make them feel like they have a home field advantage. You imagine a certain esprit de corps, a massive wave of energy. But you are honest with yourself. You realize that you don't own the stadium. The people there don't owe you anything—they are free agents; they have other agendas. They are munching popcorn, eating hot dogs, slurping drinks, or cheering for the opposing team. They might be highly inconvenienced by your vision. The guy next to you may not feel like getting up; he might be thinking, "I'm mad as hell that our prima donna wide receiver wants to be traded." So, what will it take?

First, you need people's attention. Starting a Wave requires an act of leadership, so you must be willing to stand up and lead. You have to stand up, communicate your idea, and inspire others to help you achieve it. But how? Krazy George uses his drum, but the security guard at the metal detectors made you leave yours in the car. You could, perhaps, turn to the guy next to you and say, "Hey, here's 20 bucks—let's stand up." He might go along, but really, unless you are Bill Gates you will probably run out of money before you get all 60,000 fans to buy into your plan, and you certainly don't have enough money to motivate them to get up more than once. You will soon exhaust whatever loyalty you might have bought and they will sit down or start negotiating for more. Money as a motivator has its limits.

You could turn to the people around you and say, "Listen, I'm a lot bigger than you, and if you don't get up when I say so I'm gonna punch you out." Your impressive display of brute force might get some people to follow you. Coercing by fear, however, is limited in its reach. You might get local buy-in, but the people three sections over or across the stadium probably feel securely remote from your threats, and will likely continue to do as they please, which may include simply leaving. The pumped-up bicep and snarling tone inspire little beyond a desire to flee. More important to your vision: If they do comply, with what gusto will they stand up? To create a great and powerful Wave, one that can make a difference to your team, you need enthusiastic participation. Threatened, will they leap up or, in a state of reluctant acquiescence to your superior brawn, get up slowly? Will it be a glorious Wave or a so-so Wave?

Having ruled out money as a motivator and force as a coercer, your best option to reach out to the strangers around you is probably verbal communication (although you are basically strangers, you are united in a common activity of watching the game, so you do start from a place of common interest). So what do you say and, more important, how do you say it? Again, you have some options. You could think, "Information is power. The more information I control, the greater my advantage over these other fans." You have a vision and you don't want anyone to steal it, so you turn to the next guy and say, "I'm going to ask you to do something, but I can't tell you why; it's on a need-to-know basis. Trust me." By playing your cards close to your chest, of course, you ask a bunch of people to risk making fools of themselves—or worse, engage in a waving and screaming activity that makes no sense to them—on the word of someone they hardly know. Krazy George may have built up enough personal capital from three years of banging that drum at Oakland As games to pull it off, but few others in the stadium have, and even George runs the risk of encountering a bunch of newbies from out of town who think he's just another Northern California nut job with a drum. If you try it, people will probably think, "How do I know this is going to work? Why should I trust him?" Your CIA operative approach will do little to allay suspicions of your motivations.

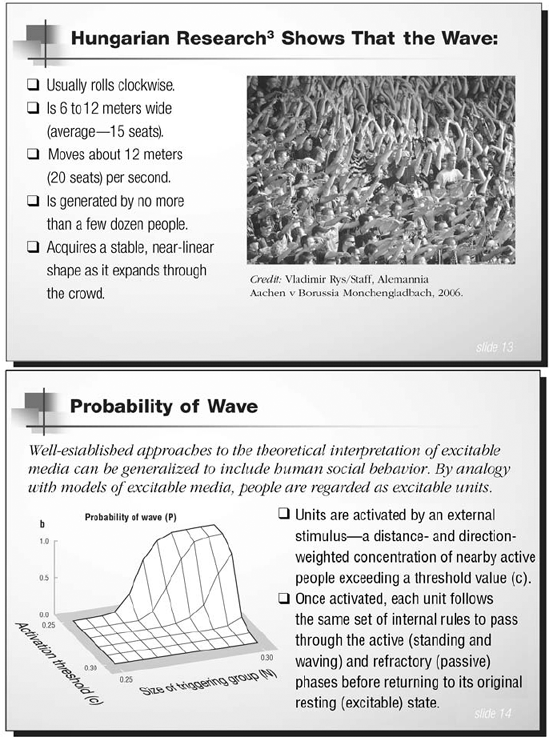

So you think, perhaps, it might be more effective to share your vision with the other fans. Maybe a PowerPoint presentation on the Jumbotron explaining the complex and fascinating physics of human interaction that form a Wave would win you converts:

Clearly, while the PowerPoint presentation may stand as a testament to your superior research and computer presentation skills, it lacks something in its ability to inspire 60,000 people. Even if this were a baseball game, which, let's face it, can be as slow as molasses, a well-made PowerPoint slide is less interesting than the peanut guy every time.

Clearly, how you communicate your vision—how you connect with those around you—directly affects the outcome, so all these approaches miss the point. The essence of a Wave, what makes it such a forceful expression of human desire, is that it is powered by a common passion to help the home team win. That value lives larger than any individual's actions and unites all the fans in the stadium. No one followed Krazy George's idea because they thought it was about George; a Wave is leadership, but the most important thing about a Wave is that you forget where it started—Section 32? 64? 132? The fans followed because he got everybody enlisted, and when you get everybody enlisted, it doesn't matter where your Wave starts. It just goes. And no one followed Krazy George's idea because people booed (that was just a good-natured way of getting attention in a big stadium). They followed because they liked what he stood for and the way he banged his drum for it.

To start one, then, you need to reach out to those around you, to share your vision with them, to enlist them in a common purpose. You must lead this Wave not by wielding formal authority, punitive power, or the threat of a small thermonuclear device under the stands, but with a touch of charisma. To get them to join you, you must be earnest and transparent, hold nothing back, and earn their trust. "Hey!" you might yell, charged with passion and commitment, filled with the unbridled emotion that you want to uncork in others. "I've got this idea! If we all stand up, wave our arms, and yell, I think it might help us win!"

Who doesn't want to win?

I like the Wave as metaphor because it is about what a diverse group of people can accomplish when united by a common vision. It illustrates the power that moves through a group of people when they perform at their best, their most unbridled and passionate. People often don't realize that there's a powerful way of accomplishing something—a how—that incorporates being transparent, being revelatory, declaring your intentions, and being very open about everything it means to you; and that how affects the Wave you create. The best hows make a Wave continue long after it has moved beyond your reach. I've found that anyone willing to do so can understand, focus, and unleash that power in business (if not in all aspects of life) regardless of position, status, or authority. This is the first point of this book.

Individuals start Waves by acting powerfully and effectively on those around them. For the Wave to take off and go, however, the conditions in the stadium must be such that the energy generated by the few can flow easily to the many. Studies show that Waves begin more easily and travel further in circular or oval stadiums than they do in lineal ones. Crowds at a high school football game, where crosstown rivals sit on opposite sides of the field according to fan loyalty, are less likely to cooperate, even though they all live in the same town. Not so in oval soccer stadiums, despite equally intense partisan feelings. Organizations can build stadiums that allow Waves to happen. Teams can create environments that allow Waves to happen. This is the book's second point.

Recently, I ordered a bracelet for my wife from a New York jeweler for our upcoming wedding anniversary. The jeweler shipped it to me in Los Angeles via UPS overnight so that I would be sure to have it on the day (missing your anniversary, as we all know, may be an even greater screwup than not delivering for your customer's just-in-time supply chain). I met our UPS delivery guy, Angel Zamora, in my office lobby the next morning, eager for the package, but it wasn't there. Angel registered my disappointment immediately, and told me to sit tight. Though his shift ended when he emptied his cart at my building, an hour later he was still on the phone with the central warehouse in downtown Los Angeles. Finally, he traced the package down to a warehouse problem and arranged for a special run to get it delivered that night. He then gave me his personal cell phone number and the cell number of his supervisor, and told me he would stay with it until it was done. By five o'clock that afternoon, the package was in my hands.

When I saw Angel again, some days later on his regular run, I told him how impressed and grateful I was with the way he owned the situation and did what was necessary to keep the commitment UPS had made. He didn't hesitate with his matter-of-fact reply: "It's what I do." It reminded me of the old story about two guys doing masonry work on a building. The first one, when asked what he was doing, says, "Laying bricks." The second replies, "Building a cathedral." Some people see themselves as bricklayers. Angel builds cathedrals. He doesn't define himself narrowly, as simply a package delivery person. He sees himself as the instrument by which UPS keeps its promises. He makes Waves that make UPS a leader in its field. By thinking of himself in the broadest, most purpose-driven terms, he distinguished not only his company, but also himself, not by what he did—get me the package—but how he did it, with forthrightness, concern, passion, initiative, and a sense of being part of something larger than himself. Those hows, the quality of his endeavor and the way he was able to reach out to others, allow Angel to make Waves, to enlist those downtown who found my package and got it on a special delivery van to my office.

UPS, in turn, creates the culture that allows those Waves to happen. Angel did not have to go through a chain of sign-offs and approvals to get his overtime okayed or his extra work validated. UPS understands and institutionalizes the hows that allow its frontline personnel to get the job done right and to fulfill commitments to its customers with a minimum of drag on the system. UPS and Angel were aligned on common values and behaviors that inspired Angel to do what he did.

In today's business world, those companies building lasting success, those that seem to be getting it right in highly competitive markets, have something going on in them, a certain energy, very much like a Wave. Waves result from how we do what we do. If, sitting in a company's stadium, gripped by a vision of the way something should be, someone in the crowd feels comfortable enough, inspired enough, and able enough to reach out and connect powerfully to those around them, then great things can happen. To build and sustain long-term success in the new socioeconomic conditions that define our world, you must embrace a new power, the power in human conduct, the power in how.

Build success based on how people interact? You may think, Come on! Business is a rough-and-tumble world. Competition is fierce, the pressure to make the numbers intense, and the environment slippery and full of potential downfalls. Sure, it's great to think about an ideal world where everyone is transparent, is driven by values, is inspired by common goals, treats each other well and fairly, and unites behind the common good; but that's just not the way it is.

I would be insulting you if I did not acknowledge that we all carry a set of personal experiences that make it seem like some of the ideas I present throughout this book are an idealist's pipe dream of a world that will never be. But in the pages that follow, I hope to show you that the world that formed and informed most of these prior experiences—the business-is-war, information-is-power, to-the-victor-go-the-spoils world of run-and-gun capitalism—no longer exists. Advances in technology, communication, integration, and connectivity have converged with predictable cycles of history to create a sea change in the way we do business, and in the way we live our lives. Things have changed faster than we have developed new frameworks to understand them, and I hope to show you in great detail exactly how radical—and permanent—these changes are. To thrive in the hypertransparent, hyperconnected world of the twenty-first century, we need to change, too.

Throughout this book, I show you how qualities most people think of as soft—trust, respect, transparency, purpose, reputation—have become the hard currency of achievement in a connected world—the drivers of efficiency, productivity, and profitability. You will come to understand that the hows of human conduct will be the determining factor in your long-term success. At first blush, these ideas may seem to contradict much of what you believe or seem counterintuitive. By book's end, you might feel differently.

Waves are fun; that is their greatest benefit. Standing up, waving your arms, screaming your head off for the home team, and, most important, being connected to everyone else in the stadium when you do so, that's fun. But Krazy George told me that the most significant thing about his first Wave, and every Wave he has made since, is how it changes everything that comes after. For the rest of the game, the crowd cheers more vigorously. They are more excited and engaged in the outcome. They feel more a part of the experience. The Wave is not only powerful in itself; it unleashes long-term, enduring power in its wake. That is an essential property of power; once the circuit is complete, the current continues to flow.

There is a Wave pounding through the people who work in companies like UPS and many others that everyone there enthusiastically perpetuates. It represents a sea change, an approach to how we do what we do that generates lasting, quantifiable value. I believe it is a power that every individual and group of people can understand, master, and learn to apply, and this book will try to help you do that. This book is about the tidal power in how.