We have probed in great detail the fundamental influences that fill the spaces between us. We've considered how we think, how we behave, how we govern ourselves as groups, and how the world has changed to put new emphasis on these ideas. If you agree with the view I have presented, you no doubt have already begun to notice the hows around you through a different lens (unless you've read this through in a single sitting). Perhaps you have noticed how something the boss said set off voices in you that you recognized as distracting, or perhaps you noted some dissonant messages coming from your work group. Perhaps you reexamined an e-mail you received or sent and took an extra moment to think about how it affected you or would affect another person. Maybe you were treated at a store in a way that made you feel richer or poorer for the experience, and you began to think about why, or that there might be a better way. These perceptions are the first step in your journey up the Hill of A toward a deep and meaningful understanding of the hows with which we fill the interpersonal synapses in the world, and others do as well.

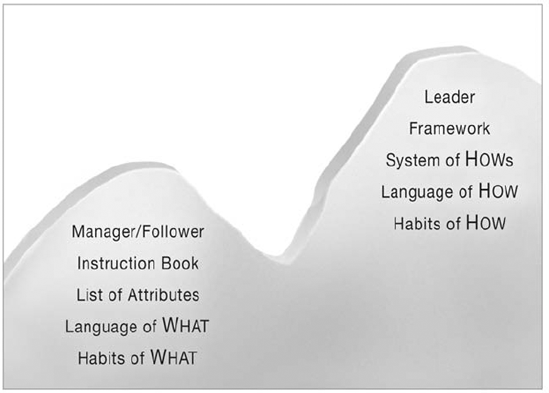

But I am also cognizant of the fact that you might still be wondering what this all means, or more precisely, how do you do how? I wouldn't blame you for that. After all, you have worked through a couple of hundred pages of a book, and I almost never told you how to do anything. I have not provided you with instructions on how to write a better e-mail or greet another person, or elucidated the manner in which you should speak. In short, I have not provided specific steps or actions that you can take to employ in your daily working life the concepts I've presented.

The reason I haven't done this is, quite simply, because I am not able to, or, more precisely, because the very nature of what we have been talking about renders writing such an instruction manual impossible. If you remember, I told you early on that I didn't have a "Manual of How" filled with Six Rules for This, or 24 Steps to That. Much to your credit, you have kept reading anyway. I have tried to provide you instead with a way of looking at the world, a lens through which to see everything we do with new weight and meaning. These ideas simply cannot be summed up in a list of things to do.

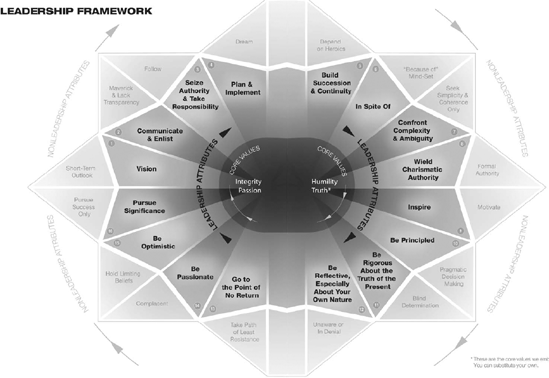

And yet, for a system of thought to be truly useful, we must find a way of bringing it to bear on every moment of our lives, to put thoughts into action, in our case, to do how. I can't give you rules, but I can give you a framework, a way of focusing your efforts, time, thought, and passion on behaviors and approaches that will help you make the choices that will set off Waves all around you. At LRN, we call it the Leadership Framework, and we use it to guide our hows every day. I developed it in the early days of the company and refined it since then.[238] It now encapsulates all the concepts that we have covered in this book and provides a way to put them into action in everything you do.

Why leadership? Because to be a self-governing individual you must lead yourself and approach everything you do from a leadership perspective. You can write an e-mail as a leader, attend a meeting as a leader, or build a report as a leader. You lead your own journey of significance every day, in how you choose to act, treat others, and see the world. A leadership mentality brings you into an active relationship with the forces and circumstances in your personal sphere of influence. It helps you to reach out to others, to create the kinds of strong interpersonal synapses so crucial to thriving in a hyperconnected world, and to inspire those around you to do the same.

Let's talk for a moment about leadership. On May 25, 1961, U.S. President John F. Kennedy stood before a special joint session of Congress and asked for a number of special appropriations to address "urgent national needs." He spoke for about 45 minutes, but few remember most of what he said. What the whole world remembers, in one way or another, is that for about eight of those 45 minutes, JFK shared his vision for landing on the moon. In about a thousand words, he launched an effort that would involve hundreds of thousands of people for the next decade and more. On that night, and in the days that followed, people coalesced around this common idea. He did not say it would be easy. "It is a heavy burden," he said, "and there is no sense in agreeing or desiring that the United States take an affirmative position in outer space, unless we are prepared to do the work and bear the burdens to make it successful.... This decision demands a major national commitment of scientific and technical manpower, material, and facilities, and the possibility of their diversion from other important activities where they are already thinly spread. It means a degree of dedication, organization, and discipline which have not always characterized our research and development efforts." But JFK spoke not just for the scientists, contractors, and astronauts who would make the journey. He spoke for the nation. "In a very real sense," he said, "it will not be one man going to the moon—if we make this judgment affirmatively, it will be an entire nation. For all of us must work to put him there."[239] In just eight minutes, JFK changed the world.

That is leadership: not simply having the vision of landing on the moon, but doing everything it takes for the roughly one million people who came together around this effort to speak the same language, to have a common consciousness, and to pursue a mission that is greater than any individual. Would America have landed on the moon if most people had said, "I'm interested in going to the moon, but it depends. I would go to the moon if I could sit in the spacecraft, in the front row, on the right side. Where I sit matters more than landing on the moon." If everyone wanted to jam into the spacecraft but no one wanted to work at Cape Canaveral and do a different job, we would not have reached New Jersey, let alone the moon. So a million people had to come together in a mutually reinforcing system to convert that vision into reality.

An organization, as we have said, is simply that: a group of people who come together in a mutually reinforcing system to accomplish something greater than any individual. So leadership is not just for people who have "president" in their title. Leadership is an attitude, a disposition, and a way of approaching the challenges you face every day. It is not a title on your business card. Though many people are formally empowered to lead others, many more of us—and in our increasingly horizontal world that number grows every day—work in teams without formal hierarchical structures. And this trend is bound to continue, with more and more of our achievements the result of our ability to be effective in groups of relative equals. Self-governance is also a leadership orientation; it begins by leading yourself. To become more self-governing and to participate in and foment more self-governing cultures around yourself, you must accept the challenge to become your own legislature, to look inside for answers and be guided by your alignment to the values you find there. This framework can help you develop the orientation to do this well.

As we go through the elements of the framework in the pages that follow and hear from many people who lead, remember that great leaders became leaders precisely because they either consciously or by their very nature embodied those behaviors that make Waves, that move those around them to do great things, and that work powerfully with others for change. That is the essence of leadership, and it begins with leading yourself.

We began this book with a story about a person I think is one of the greatest leaders ever, Krazy George Henderson, the man who invented the Wave. To thrive in the internetworked world of twenty-first-century business, you don't need one big Wave; you need to make Waves every day, and like that stadium cheer, anyone can make one at any time. It could be a question in a town hall meeting that would make it a better meeting, or an e-mail that inspires others to take up the cause at hand. Leadership is getting your hows right, and you can look at anything through the prism of leadership. You can brush your teeth because it is something your parents made you do as a child, or you can brush your teeth because you have a vision of dental health and a winning smile. Leadership is about starting and making Waves contagious in everything you do.

The Leadership Framework is not a set of rules or edicts you must memorize or comply with, cans and can'ts that live outside of you; the Leadership Framework lives in the world of shoulds. It begins with core values and then gives you ways of approaching each decision or action to bring those values to bear on others. It provides a foundation from which to make decisions every day and brings values to life in behaviors. These behaviors, consistently done, reinforce each other to create an upward spiral of energy that propels endeavor. If you divide life into what you do and how you do it, the Leadership Framework describes an approach to how: how you communicate, how you work, how you treat others, how you make decisions, how you interact in the marketplace, and how you can act consistently. It governs, guides, and inspires how we do things. A framework is another way to describe a system; each part mutually enforces every other part. Like the studs, rafters, and beams of a house, or pieces on a chessboard, the strength of each is magnified tenfold when they work together.

Though I call it the Leadership Framework, you can also think of it as a lens, the Lens of How. When you see the world through it and act accordingly, you will engender more trust, build a stronger and more enduring reputation, become more actively transparent, think more clearly, act more spontaneously, and make more Waves with those around you. You won't have to worry about all those things individually, because they will make perfect sense when seen as a whole. You will begin to affect culture, to lead and model a standard of conduct that will speak to the higher selves of those around you, and lift their efforts as well. The lens of how will inspire you by rendering clear the terrain you must navigate on your journey to climb the Hill of A, and many hills beyond.

This framework is not the only possible framework you could construct for this journey; it was designed for the types of high-information, person-to-person efforts that go on at LRN every day. It represents the amalgamation of many of the thoughts and concepts I have picked up or developed over the years, and that apply well to our core activities.[240] If you work on a shop floor or in some other specific environment, some of the ideas here might be superfluous to your efforts. No matter what you do, however, understanding the behaviors and dispositions described here will begin to give you a visceral experience of what getting your hows right is all about.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the Leadership Framework draws some of its power from a disposition toward language. We know from the research we discussed in Chapter 5 that language exerts a powerful influence on the way we think about things. There is, for example, a vast difference in the influence of the word enlist versus the word sell. When you sell, the object in play is the product, a thing that lives outside both you and the buyer; when you enlist, you invite a relationship in which the product is but one stage today on a journey of innovation tomorrow. The behaviors, thoughts, and consciousness that follow from being in touch with enlist are entirely different from embracing sell. Similarly, do you have customers or do you have partners? What does the word partner say about that person across the table from you differently than the words customer, vendor, or supplier? Will that affect how you negotiate? How you define success in that negotiation?

Like can versus should, language has the power to contain or inspire, and the language you adopt and employ either locks you in rigid relationships or frees you to new possibilities of connection. In other words, if we broaden our vocabulary, we have access to a bigger world with more options. I also believe that the people who will become the leaders of tomorrow—those who will thrive and excel in our hypertransparent, hyperconnected world—will be the ones who embrace this language and unlock its transformative power.

To help you see how the concepts in the framework interrelate and build upon one another, I have assembled them in graphic form in Figure 12.1.

You see that it is organized into three concentric spaces. At the center of the lens, at its point of sharpest focus, lies a set of Core Values. In the illustration, I have used the values that we embrace at LRN as central to our mission. You can easily substitute your own, but they must be the deep sorts of values like justice, honesty, integrity, community, and honor that truly inspire the highest in human conduct and interrelations. You'll find the list of possible choices is not long. The most important things about whatever values lie at the center of the circle are that they express the highest aspirations and fundamental beliefs of the group to which you belong; that they are truly the core; and that everyone can agree, embrace, and align themselves with them. They are the guiding principles that unite you in common endeavor.

Surrounding the central core are Leadership Attributes, the behaviors, attitudes, and orientation of a self-governing individual. It is these attributes we will primarily focus on and explore in the pages that follow. Surrounding these is a set of Nonleadership Attributes, behaviors that often result when you abdicate your pursuit of how.

Let us begin at the beginning of the framework and see where it leads. (I know, a circle has no beginning—that is part of its unique character—so I have numbered a starting place at about nine o'clock on the circle to get us on track.) Feel free to refer back to the illustration frequently to better follow the narrative.

The Leadership Framework begins with five essential attributes, five keystones of behavior upon which the entire structure rests. The first is vision. A self-governing person spends some time in another realm, the future. Having a leadership disposition means mentally envisioning a better future for yourself, the tasks at hand, and those with whom you labor. Leadership starts with vision, and leaders envision every moment. You could have big visions or little ones, envision a better meeting or envision inspiring thousands of workers around the world to make better decisions. You could envision a feature in a technological platform, or envision a whole new product, or simply envision a way to make someone else's day a little bit better. You can create a new vision or embrace someone else's and make it your own.

Envisioning represents a proactive stance toward achievement; it is an activity, a behavior, and a disposition toward pursuing your goals. If you don't have a vision, then you fall outside the lens of how and are a short-term manager: task-oriented, obedient, and obsessed with and limited to what you can see right under your nose. Short-term managers tend to be reactive by nature and find themselves putting out fires more often than they light the beacons that show the way. It is a defensive posture and worries more about appeasing others than about engaging them. To get your hows right you must be focused on others, and vision is the crucial first disposition toward achieving that goal.

Most visions that are worth pursuing are greater than any one of us, so if you have a vision and you feel it truly has content that could make for a better future, then you should share it with somebody else. The question then becomes: how do you share it? What is the quality of your effort? If you browbeat somebody, if you talk at them, you are not sharing. Sharing, at its heart, attempts to make your vision into everyone's vision, to make a Wave. Uniting a group of people behind a single goal or set of goals presents the greatest challenge to any leader; achieving that alignment results in the greatest success.

To reach this goal you must enlist those around you and help them see what you see. To truly enlist you must be open and forthcoming about your motives, be transparent in your communication, and reach out to others in a way that they feel you've truly shared.

Consider the last 50 e-mails you received. Which ones enlist? Which, when you read them, make you think, "Yes, I get it. This makes sense. I want to help." Which ones, by contrast, make you think, "What is this all about? This is not what we agreed to. Why did you cc: my boss? What are you up to?" The ones that enlist create connections. They build strong synapses between the sender and you. They make you want to participate, belong, or assist in the effort.

In every e-mail, instant message, phone call, teleconference, or face-to-face encounter you can communicate to enlist and share, or you can do something else. Ask yourself, when you write an e-mail, do you have a vision to make it effective? A vision for the response? Leaders reach out to others with a quality of communication that allows people to share, to be enlisted, and to make your vision theirs. Taking this additional moment before you hit the send button is not an extra something, a burden or tax for you to contend with. Instead, it makes everything you do more effective. If others embrace your communication and make its goals their own, more gets done. Think of it this way: You go on a diet to lose five pounds. Dieting is not an added burden; it takes no more time to eat one way than another way. Dieting is a series of choices to eat one thing and not another, and a good diet regimen provides you with guidance—based on a set of beliefs about health, exercise, and nutrition—to help you make those choices and achieve your goal. When you reach out to others, you can choose to enlist them, or you can choose to respond in way that has little effect but to clear your in-box for the time being. One starts a Wave; the other kills one.

If you don't share your vision with others, you are acting as a maverick. Your vision will remain yours alone. There is nothing wrong with being a maverick (in fact, we admire many of them), just as there is nothing wrong with many of the behaviors that occupy the outer circle of the Leadership Framework. From time to time, they may even be the most useful or appropriate behaviors to practice. However, they are not self-governing, leadership behaviors, behaviors that can start TRIPs or make things happen in a hyperconnected world. Since the conditions of the world have changed in such specific and remarkable ways so as to place new, higher value on connection and interrelation, it is those behaviors that best capitalize on the conditions that we are concerned with here. These are the behaviors codified in the Leadership Framework.

Self-governing leaders step forward. They raise their hands at meetings. They say, "I have an idea," "I'd like to run this task force," "I'd like to complete that assignment," or "I think we should land on Mars and not Venus." Leaders stand up for what they envision, and are not afraid to occasionally take center stage. They offer themselves up. They seize the authority and take the responsibility that comes with leadership. Carpe diem is the watchword of their faith. If you never step up, you consign yourself to a career of always following.

Having a leadership orientation does not necessarily mean you must lead in every instance; you can maintain a leadership disposition and still follow the leadership of others. Within any team or work group, certain people will take the overall lead, but within that effort opportunities arise for everyone to lead. You could envision yourself disseminating project metrics in a way that enlists others in the team goals or step forward to provide them with essential data to make better decisions. Though you work within a group or have natural or appointed superiors, a leadership disposition opens you up to a greater level of contribution and achievement. A self-governing leadership culture allows everyone to take these opportunities to lead, and when you step up and seize the moment, the moment seizes you.

Walt Disney was a visionary. He imagined an anthropomorphic mouse and he put that mouse into action, changing the face of animation, filmmaking, merchandising, amusement parks, and family entertainment. But he didn't create one of the largest entertainment companies in the world solely by his dreams. "The way to get started," he famously said, "is to quit talking and begin doing."[241] Leadership is ideas put into action.

If you have a vision and you share and enlist others in it, the next step requires that you plan and implement its achievement. The gutters of business are littered with the great ideas of those who envision but cannot implement. They are the dreamers of the world. They talk a good game, but when push comes to shove, they don't have what it takes to get things done. Many people have imagined a business they wanted to start, a project that would make lives easier, or simply a better way to reach a goal; many have imagined landing on the moon in one way or another. You meet many people with dreams, but you also meet those who work with others as a team to make their vision real. In a world of how, these are the winners. A small vision achieved is worth ten grand notions unimplemented.

Self-governing people step up, seize the moment, and find ways to get things done. Though this may seem at first a recipe for doubling your workload, in fact the opposite is often true. This basic eagerness to plan and implement their visions or the visions of others serves as a powerful example to those around them. When others see these sorts of hows in action, they feel similarly inspired and join in. More gets done with less effort because the whole team pulls together. In football, when a running back is crashing the line with extra effort, his tackles block extra hard, his quarterback makes better handoffs, and everyone on the team steps up with the extra effort needed to help him score a touchdown.

I collect mechanical wristwatches. It's a hobby. I find them very beautiful, a profound expression of our desire to order the world around us, and objects that embody the deep tradition of man striving for perfection, to make many small and intricate parts operate as a constant whole. If you ask me the time, however, I usually reach into my pocket and pull out my cell phone. It is in continual contact with an atomic timeserver and is the most accurate information I can put my hands on. I'm the CEO of my company, the ultimate leader there, if you will. If I show up late to a meeting, can the people waiting for me there find out the time? Of course they can.

Metaphorically, leaders don't show up and tell you perfect time; as James C. Collins and Jerry I. Porras told us so brilliantly in Built to Last, leaders build clocks that keep telling the time whether they are there or not.[242] If landing on the moon depended on JFK, what would have happened when he was tragically assassinated? Leaders are not superheroes; they build succession and continuity into everything that they do. They don't build anything that depends on a single person to show up and tell perfect time.

This idea is one of the most central and powerful ideas in the Leadership Framework, and the one most often underestimated. I think it is because saying the world doesn't need heroes contradicts most of our experience. Business often calls on us to be heroic, to go the extra mile, burn the midnight oil, or pull the extra shift in order to meet our goals. And I agree. The world certainly needs heroes. You can't get the train out of the station without some hard pushing, without heroism sometimes. The paradox is that though we need heroism from time to time, to truly thrive we must build self-sustaining approaches at the same time. Understanding the need for systems that generate energy as they achieve, rather than depleting resources to do so, leads you to a disposition that does not depend on heroics. You cannot build a great, enduring, significant company on the backs of superheroes. No matter how strong they are, eventually they will collapse under the weight. To build a skyscraper of an idea, hundreds of floors stacked on one another, you need a foundation of continuity that can grow as you do.

In 1964, Disney began to buy unproductive orange groves near Orlando, Florida, for what was called the "Florida Project." It was one of Walt's grandest notions. But, as the project developed, he developed lung cancer and soon died. His brother Roy and a team of Disney's hand-selected and trained designers picked up the ball and saw it through to completion; Walt Disney World opened in 1971, the largest theme park ever imagined. He had enlisted them in his vision and they had made it their own. Roy Disney died three months later, but succession plans were in place, and Donn Tatum became the first non-Disney family member to be chairman and CEO of The Walt Disney Company.[243] The dream lived on.

Ask yourself a practical question: Do you want to be promoted from your current position? Now put yourself in your superior's shoes for a moment. Can he or she promote you if you are the only person who can do what you do? If the job won't get done unless you stay there and continue to be the hero, it makes no sense for the business to ever promote you. If heroism is what's getting the job done, you will stay right where you are to keep getting the job done. If, however, you build a self-sustaining approach to your job, a clock that can tell time without you, it is far more likely that you can get promoted—in fact, more likely that you will. Not only will you have excelled at the discharge of your responsibilities, but also you will have built something larger than yourself and made a contribution to the whole organization.

For example, many large and medium-sized businesses require sales and services teams to use a web-based customer relationship management (CRM) application like Salesforce.com. Essentially a centralized database platform, these tools provide each company rep a way of recording and storing detailed information about sales contacts, leads, and ongoing negotiations in which they are involved. Too often, I think, a tool like this is perceived as busywork, an administrative tax on the hardworking reps who, after a long week on planes, trains, automobiles, cell phones, and BlackBerrys, must then spend additional hours plugging all their notes into the system. Seen through the lens of how, however, this is a leadership opportunity, a chance to build continuity, to inform and enlist the team. Should you catch the flu a day before a closing pitch, the continuity you've built into the CRM application enables someone else on the team to easily step up, grab the ball, and bring home the business.

If you build a system that can be run by others, train others so that they may step up and take more responsibility, or enlist those around you in a team-based approach that is more efficient and profitable, a superior can then say, "The business doesn't seem to need you as much to accomplish that goal; we could use you better in this new position." The key ingredient to progress, to getting ahead, is to leave a foundation behind.

These five behaviors—envision, communicate and enlist, seize authority and take responsibility, plan and implement, and build succession and continuity—form the foundation of a self-governing disposition. The rest of the Leadership Framework amplifies, refines, and reinforces these basic concepts, creating a circle of leadership attributes.

A thought here about circles: Waves, we know, go around. Studies show us they start much more easily in closed-loop stadiums where everyone can see one another, and much less easily in, for instance, motor speedways, where the audience lines one side of the stadium. Leadership, in some way, mirrors this geometry. The Leadership Framework creates a self-perpetuating circle of energy, like a Wave in a stadium. When two kids hold hands, lean back (trusting one another not to let go), and spin around, they can achieve great speed with little effort, and the energy between them continues to grow as long as they hold on. When they let go, all that energy disburses. The Leadership Framework mirrors that idea. As we talk through the Leadership Framework, you will notice that for everything a leader is, there is something he or she is not. When your actions take you out of the framework, you sacrifice its self-propelling energy and, like those dizzy kids, crumple in a heap on the grass.

The other remarkable thing about the framework is that it allows us to be really aggressive and fiercely competitive in pursuit of our goals. Its interlocking nature leaves us freer to innovate, to take chances, and to act spontaneously without losing sight of our core values, the center around which we spin. Because it helps us see things through our core, we can see the shortest, most expedient path to achievement. Though the wild uncertainties of daily business can sometimes leave us lost in unfamiliar terrain, the Leadership Framework always tells us where home is, and helps us see the sure path to get there. By holding on tightly to the circularity of the framework, we can generate that much more speed and energy on our journey.

Everything worth doing encounters resistance along the way. To move a big rock requires you to fight gravity and inertia. To climb a mountain requires you to overcome the effects of thin air. Say, for instance, you return from giving a presentation to a potential partner. The discussions went well and you feel the prospect should be doing business with you and not your competitor. But one person in the meeting announced to the room that the company doesn't have room in its budget this year. What is your attitude when you hear this? What is your disposition to obstacles?

In 1905, Madam C. J. Walker started selling a scalp conditioning and healing formula, Madam Walker's Wonderful Hair Grower, door-to-door to African-American women throughout the South and Southeastern United States. Walker, the daughter of former slaves, had been orphaned at age 7, married at 14, and widowed with a child at 19. She worked doing laundry to put her daughter through school before she envisioned a new life for herself. "I got my start by giving myself a start," Walker said. In spite of obstacles far greater than any that most can imagine, Walker grew her enterprise into a company that employed 3,000 people. She became the first known African-American woman to become a millionaire. "I am a woman who came from the cotton fields of the South," she was fond of saying. "From there I was promoted to the washtub. From there I was promoted to the cook kitchen. And from there I promoted myself into the business of manufacturing hair goods and preparations. I have built my own factory on my own ground."[244]

It would be hard to imagine anyone who envisioned and accomplished so much in the face of seemingly overwhelming obstacles than C. J. Walker. She pursued her vision in spite of obstacles, and this deeply ingrained attitude was central to her ability to thrive. If you want to make a Wave happen and the person to your right doesn't want to stand up, are you done? Do you sit back down Waveless? Yet we've all seen Waves happen in which people at first don't want to stand up, but then get caught up in it. It becomes a great Wave. This can occur only when its leaders persevere in spite of initial resistance. A self-governing leadership disposition helps you ask the question, "How do we help our partner find the budget they need to support the program?"

I've never met a good sailor who hasn't sailed in rough waters, and I have never seen a vision, never heard an interview, and never read a biography about someone who achieved something worthwhile that did not include stories about gutting out rough times, overcoming obstacles, and getting there in spite of all that got in the way. It's a fact that you will face obstacles; it is a constant of life. What matters is not the obstacle, but how you think about obstacles, how you approach them, and how you behave in the face of them. Leaders believe they will find a way in spite of the forces aligned against them. They never walk away because of a problem. Sometimes you won't succeed despite your best efforts, but if you don't start with the in spite of disposition, you will seldom win.

We live in a world full of conflict. Had we infinite resources, perhaps we could say yes to everything and wouldn't need to make tough choices. Perhaps we wouldn't even need a Leadership Framework. But the world is full of conflict, full of competing desires, interests, objectives, agendas, and possibilities. So, much as we need to cultivate an in spite of disposition, we must also embrace the complexity and ambiguity. Even the best-made plans can go awry, and to expect smooth sailing and steady winds sets you up to struggle when inevitable adversity hits. Over dinner in Los Angeles, venture capitalist Alan Spoon told me, "There is always going to be good news and bad news. The good news takes care of itself; it's the bad news that takes work. That's where you'll spend your time."[245] Leaders know this going in; they understand that conflict is natural, and anticipate the need to lead in the midst of conflict.

Again, it boils down to disposition. Leaders stare in the face of conflicting desires and individual interests, and of limited, not unlimited, budgets. They open some doors and they close others. They make principled decisions in the face of conflict and so set a steady course through rough seas. Leaders are thirsty for truth and they go after it. By definition, the future that they have envisioned and the present are in conflict; change must occur to achieve something new. Within this tension lies the opportunity to thrive, but only in the hands of those willing to confront it.

Similarly, leaders eschew essentialism and reductionism in the approach to their goals. The goal is never about one thing, like profits or productivity or quality. Leaders acknowledge the inherent complexity of every journey. They balance many voices and many goals and seek to fulfill the needs of the many stakeholders in every effort. In the face of a multitude of choices, the self-governing person looks wisely and deeply to the core values at the center of their framework and makes considered decisions about the best way to uphold them.

We have taken as one of our foundational attributes that leaders seize authority. But what kind of authority? Stand up or I'll punch you? Do this because I'm your mother or father, or because I'm your boss? In Japan during World War II, the Japanese military began sending their airmen, known as kamikazes, on tokko: suicide missions. Many young Japanese men died during these missions, but a few lived to tell the tale of what it was like. One of them was a Japanese Navy pilot named Shigeyoshi Hamazono. In his wartime memoir, Suiheisen (The Horizon), Hamazono describes being prepared to die for his country, but recalls an encounter he had before leaving on a mission on April 6, 1945. He tells of Vice Admiral Ugaki, who gave a farewell speech to the Kokubu No. 1 Air Base kamikaze pilots, of whom Hamazono was one. Ugaki shook their hands and said, "Please die for your country." After finishing his remarks, he asked if anyone had any questions. A veteran pilot, whom Hamazono respected, stepped forward and said, "I am confident that I can sink two enemy transport ships with just the bombs carried by my plane. If I sink them, may I return?" Ugaki reportedly answered, "Please die."[246]

Authority typically comes in two forms: charismatic authority and formal authority.[247] Formal authority derives from reference to power, usually hierarchical power. "I'm your parent. In my house, I'm right, even when I'm wrong." That is formal authority (and also the reason why most of us grow up and leave home).

Many young men died on both sides of that brutal war, and Ugaki is an extreme example, but we see examples of formal authority like "Please die because I ordered you to" wielded every day in matters from the mundane to the sublime. You get an e-mail that consists of one sentence, "Do this by four o'clock." The implication is clear: "because I'm the boss." Are you enlisted? Or has the wielding of formal authority introduced friction into the relationship? You might acquiesce for any number of rational reasons—you are new at the company, your boss is quite senior, she could help your career—but are you enlisted? Are you inspired? Formal authority lacks the ability to inspire and enlist. It can, at best, demand acquiescence, a grudging or even willing going along with the order. Each time leaders wield formal authority they deplete their store of it. It's like a bank account; the more you withdraw the less you have. Eventually, willing acquiescence turns to grudging acquiescence, which turns to subtle undermining, and even outright rebellion. The delays and distractions of those you lead in that way steadily mount, and their productivity and responsiveness steadily decline.

Charismatic authority, in contrast, compounds itself. What if, instead, that four o'clock e-mail says, "If you can get this done by four o'clock, it will help our team win in these three ways." The e-mail enlists you by sharing how the task fits the larger vision; what originally seemed an arbitrary deadline now becomes an integral part of a vision to succeed. Vision and enlistment breed charismatic authority. Charismatic authority derives not from power but from principled action toward others, from referencing beliefs and principles and reaching out to others with them, and from a desire to get your hows right and make Waves. It is earned every day, in every how. You build charismatic authority with every action toward others, so rather than deplete their bank account of authority, you build it. Sometimes it takes a little extra time, but the time is an investment that is paid back with interest, a short-term cost for long-term gain. Thus authority itself becomes a Wave, self-sustaining, going around and around until no one can remember where it started but everyone is glad they were a part of it.[248]

Say what you will about Krazy George Henderson, but there is no denying that he is a paragon of charismatic leadership. No one participates in his Waves because he is hired by the stadium to start them, nor do they follow because he bangs his drum loudly. They follow because he reaches out to them, shares his vision, enlists them in the big picture, and perseveres in spite of those who think he's a crackpot or who would rather eat their hot dogs in peace. And he gets things done; people stand and cheer.

We know that rational people, for the most part, avoid pain and seek pleasure. Rational people, the common thinking says, will be motivated by more pleasure and less pain, more money and less censure. When you are in a position of authority, then, and you want to get things done, you give people more carrots and fewer sticks, right? Informed acquiescence cultures are built on this simple thought. Motivational thinking, in the form of carrots and sticks, dominates these organizations. While we can't deny the reality that no one works solely because they enjoy it or it fulfills them (or we would call it "play" rather than "work"), motivation as a leadership principle is not self-sustaining. The person who hands out $20 bills in order to make a Wave eventually either runs out of money or the cooperation of recipients who decide that $20 isn't really enough. Motivation requires an object of motivation, a carrot or a stick, some external means by which to propel or compel action. Motivation has its place, but we know that in a world of how motivation is not enough. A leader seeks a self-sustaining method of generating action. To make Waves, you must seek to inspire.

Inspiration comes from a dedication to beliefs and values, the pursuit of big ideas and significant contributions to others, and a commitment to communicating this dedication and pursuit to others. Isn't it different to be inspired than to be motivated? Everyone knows what it is like to be inspired. You can be inspired by a movie, by a book, or by an experience that happened to you, inspired by what you want to accomplish, or inspired by the actions and efforts of others. Values are inspirational, as is the pursuit of goals greater than yourself. Inspiration calls forth your best efforts and your most creative thinking. If you are inspired to land on the moon, or inspired to start or participate in a Wave, you don't care about carrots and sticks; you have a higher calling. Just as trust elicits trust, inspiration elicits belief. Informed belief—the marriage of the questioning and unquestioning parts of the mind—is a powerful, self-sustaining force. Like everything else in the Leadership Framework, inspiration circles back on you. Seeing others inspired inspires you in return. Leadership is about inspiration. Leaders inspire, and seek to keep the atmosphere of inspiration—the call to significance—alive in others. You don't have to be the boss to do this; anyone can, and in a world of how, where the quality of your effort is as important as its end result, everyone should.

In the wake of Hurricane Katrina and the destruction of the city of New Orleans, the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) handed out money to people in a helter-skelter fashion with almost no basic fraud-prevention systems. Emergency aid was subsequently used to purchase season tickets to the New Orleans Saints football games, a large dinner at a Hooters restaurant in San Antonio, a $200 bottle of Dom Pérignon, an all-inclusive weeklong Caribbean vacation, and several "Girls Gone Wild" videos. Thousands of incarcerated criminals received emergency housing allowances.[249] "We just made the calculated decision that we were going to help as many people as we could," said Donna Dannels, acting deputy director of recovery for FEMA, speaking to a Congressional oversight committee a year later, "and go back [later to] identify those people who we either paid in error or [who] defrauded us."[250] Dannels made this statement after a nonpartisan Government Accounting Office study revealed that as much as $1.4 billion—one-quarter of the total monies FEMA distributed in the wake of the disaster—was lost to fraud and abuse.

Decision making, in general, flows from one of two sources: pragmatism or principle. Pragmatic decisions seek to solve the immediate problem in the most expedient manner, like FEMA in the face of Katrina. Pragmatic thinking tends to embrace short-term benefits and alleviate immediate pain, but it produces unintended consequences with often long-term ramifications. If FEMA were a for-profit company, for instance, its losses from fraud would be dwarfed by the loss of its credibility and reputation. Who would choose to invest in an insurance company that reimbursed the purchase of "Girls Gone Wild" videos? What possible explanation can remediate the impression that choice leaves on the market?

In the course of a business day, we are all called upon to make countless decisions. If we are self-governing and adopt a leadership disposition, we make even more. What kind of spacecraft do we build? What should the design look like? What kind of people should we hire? What should I say when I return this phone call? Leaders are constantly making decisions, and a given team or organization might make hundreds, if not thousands, of decisions each day. If each one of us makes decisions based on short-term, pragmatic considerations—what will sound good, what will make the problem go away, what will close this deal—the errors of unintended consequences—like Girls Gone Wild—just spiral out of control. We can't control or imagine the ramifications of all those short-term decisions.

What would happen, for instance, if, after a successful quarter of doing or saying whatever it took to make your numbers, you put all of your customers in a room and walked out. What would they think of you if they started to compare notes?

"Hmmm, they let you do a six-month pilot? They told me they don't do pilots."

"You got a three-year contract? They told me they would only do a five-year contract, no matter what."

In a transparent, connected world, this happens every day, both physically and virtually. And not just about company practices, but about your individual behavior, as well. Comparing notes is cheap and easy, and we do it countless times a day via the vast store of information and communication technology easily at our fingertips. That puts a premium on consistency. The world of how calls for conduct that creates long-term, self-sustaining continuity, which builds trust and further alignment between you and the world around you. I propose a corollary to Mark Twain's famous quote about telling the truth (though not as eloquently phrased): "Always act on principle. That way, you won't have to keep track of all the intended and unintended consequences of your actions."

Seeing through the lens of how leads you to make decisions based on principle—a sound, central core of beliefs that expresses long-term values. In a transparent world, where everything that can be known will be known, only principled decision making can guide the kind of consistency of purpose you need to build trust and reputation. Acting from principle rather than pragmatism also makes you more efficient and nimble. Because you will not spend as much time dancing with rules or comparing short-term gains, you can act more intuitively and with more clarity rather than in a slow and calculated fashion. The best possible decision will be more immediately apparent to you because it will spring from your deepest values. You will act with more certainty, confidence, and trust in your choices.

If you want to become enduring and self-sustaining, you must focus your thinking through the lens of principled thought, and let those values-based considerations inform everything you do or say.

Shortly after Steve Wynn opened the eponymous Wynn Las Vegas resort in 2005 to great fanfare and acclaim, he realized he had a problem.[251] Dealers and floor people in Wynn's casinos are usually the best-paid in the industry and derive most of their income from tips that are pooled and divided among the frontline service personnel who run the gaming tables. "I made a mistake," he told me from Macau, where he was working on his newest project. "It turned out, unfortunately, that the dealers were making all of the tips and the floor people and supervisors who serve the customers side by side with the dealers were not receiving any, meaning the dealers were making more than their supervisors. This disparity caused dissatisfaction and resentment among the floor people, who thought it unfair. Plus, because of the inverted compensation structure, I had difficulty recruiting dealers to step up and become supervisors. The casino was suffering."[252]

You can only take risks, as we know, when you have a strong foundation of trust. Trust enables risk, which allows innovation and leads to progress: TRIP. But when mistakes are made and realized, a leader has only two choices: to let them be and absorb the cost or to expend the resources necessary to correct them. In Wynn's case, he had to choose between an inverted and unfair compensation structure that was detrimental to the growth of his operation, and disrupting the morale of his dealers by altering their pay package and jeopardizing their trust. "It was a terrible scenario," Wynn said. "I thought about it for months, but I couldn't let it stand. This was the first time in my whole career that I had to double back and do something that would hurt my employees' compensation package. It felt like cutting off one of my fingers."

No matter how painful or personally embarrassing the truth may be, leaders step up and face it head-on. Over the course of many face-to-face meetings, Wynn told his dealers he was revamping the way the tip pool was divided to create greater rewards for those who stepped up and accepted more responsibility. "I told them I had made a mistake, that it was my job to treat everyone fairly, that a group of them were getting screwed, and that I was going to make a change. I said, 'Look, I'm here, and I'm going to meet with every employee in this company, every dealer, because I owe you now and forever an explanation of the thinking behind our decisions, especially one that impacts your life.'"

Despite his transparency, the dealers were predictably (and perhaps understandably) upset. Even after many discussions, some of them filed suit in the district courts and with the Labor Commission. Ultimately, those lawsuits were dismissed. Even after the rigors and combativeness of a lawsuit, however, Wynn did something remarkable. "I took the guys who sued me for coffee," he said. "I told them how much I respected them for standing up for what they thought was right. I told them that not only did I not have any hard feelings, but I actually felt they were correct to promote what they thought was right, and to have the guts to stand up for it and not just grouse in the back room. I am also meeting with all the employees to tell them how proud I am that, even though they disagreed with me and even though they thought that I had made the wrong decision, they never, ever took it out on the floor of the casino with the customers."

Wynn, and anyone in his position when a problem is found, had many ways he could have avoided taking action directly. Many of us have been on the receiving end of memos, e-mails, or delegated proclamations from the top of the organization giving us bad news about our jobs. But Wynn chose to deal with the problem head-on and directly. I asked him why he chose that road. "When you make a decision that you feel is the right decision for the long-term benefit of the enterprise, it still may be wrong," he said. "It could explode in your face; it could be embarrassing, humiliating, or even catastrophic; but that is absolutely not an excuse for not making that decision, nor standing up for it in front of others. That's probably at the heart of leadership."

You can't build a skyscraper like Wynn Las Vegas on a foundation that is not solid, or worse, that you "sort of believe" is solid. You can't land a rocket in the Sea of Tranquility if you don't know whether the surface is rock or powder. A leader needs to know, so a leader is rigorous about the truth of the present. The more rigorous you can be about the truth of your present condition—what is solid and what is not, what works and what malfunctions—the better you can pursue the future. A leader peels the onion to get to the truth, no matter how difficult or evanescent that truth may be. Leaders believe it is healthy to ask the tough questions, toss ideas back and forth, confront problems when they arise, and wrestle truth to the ground. Getting bad news, understanding what is broken, understanding what's shaking, understanding where the house of cards is and where real killers of the future lurk. To make your visions reality, you must not be afraid to see everything there is to see.

The opposite of rigorous truth means indulging some blind spots or living in a state of plausible deniability and superficiality, a habit that leaders should banish from their thinking and approach. Leaders must know how solid is the foundation before they take leaps, build skyscrapers, and innovate, and be rigorous about the journey along the way.

As much as most of us relish conditions of harmony, simplicity, synthesis, and coherence, nowhere do they exist at all times. Even monks who live on mountains have to struggle to get a decent meal now and again (though they produce much spiritual calm, their P&Ls leave something to be desired). More often, our world is full of conflict, complexity, and ambiguity. To become a person capable of getting your hows right, of focusing not just on the what of the outcome, but simultaneously on the how you do what you do, you must learn to feel comfortable within these conditions. To be self-governing means to be reflective, especially about your own nature.

Our virtues are typically our vices. Lawyers are trained to argue and tend to win a lot of arguments. People disposed to winning arguments, however, often face a challenge in the realm of personal relationships, because relationships are rarely about winning or losing. So seeing through the lens of how, a lawyer devoted to strengthening her synapses with others reflects: When do I talk too much? When do I listen? When am I argumentative? When am I zealously advocating? Am I enlisting? Am I not? Is the Wave really happening? Are people really getting up because they're inspired or are they getting up because I motivated them? We must reflect about our virtues and our vices and be rigorous about our own truths.

"Shortly after I became CEO of Pfizer," Jeff Kindler told me, "I was being interviewed on internal video for our more than 100,000 employees. They were asking me about changes to the company, and I said something like, 'There may be a need to make important changes in the company; we may need to take up a lot of actions to change,' and blah blah blah blah. I was using a lot of buzzwords and corporate-speak. And then I realized what I was doing. I was on the border of spinning, and I interrupted myself and said, 'Wait a minute, let me correct myself. Let me be clear about what I am talking about here. There will be cost cutting, and there will be layoffs, and people will lose their jobs.'" It was Kindler's first major communication with his company, and it was his first opportunity to show what kind of a leader he was going to be. Though it meant being vulnerable in front of 100,000 people, Kindler's ability to reflect in the moment allowed him to set a true course of change for his company. "It was harsh language," he admitted, "but it was truthful, and I think people respected the fact that I was not giving them a load of baloney in corporate-speak. Since then, I have received comments that people at Pfizer appreciate that somebody is talking straight to them, that I am acknowledging that we have serious challenges and serious issues we need to face."[253]

Self-reflection lights the way on a journey of self-improvement, guiding you through both the good times on the Hill of A and the struggles in the Valley of C. Governing yourself means working on yourself and trying to do things better year over year and week over week. Like the monks, we will never achieve perfection, but if we reflect not only will we improve, but we will develop the sort of simultaneous consciousness that Jeff Kindler has, the ability to see the hows in everything we do, as we do them.

A lack of reflection leaves you superficial and determined. You may win a lot of arguments, motivate a lot of action, show the superficial characteristics of corporate-speak leadership, and even achieve some success, but you will work harder to do so, and eventually people will begin to see your limitations as a leader.

Do you remember the first time you went to the edge of a very high diving board at a swimming pool? Goaded there by your friends who, despite all sense, yelled for you to jump, you inched your way to the edge, looked down, and immediately wished you were somewhere else. In that moment, you realized, perhaps for the first time in your life, that you had consciously taken yourself to the point of no return. If you crawled back and didn't jump, you realized, your friends would call you a bunch of names you didn't want to be called. If you jumped, however, you felt you might die. Butterflies in your stomach, trying hard not to giggle, there was nothing comfortable about that moment. Nothing was more terrifying.

Some of us jumped. Some of us crawled back, only to return another day and succeed. Some of us, to this day, have never taken the plunge. But to envision, by definition, means to explore the unknown, to go to new, risky, and potentially frightening places. You can't land on the moon if you don't go farther than the hill behind your house. If you are trying to bring about a better future, you must every day go someplace you have not been before, to the point of no return. What happens every time you go to the point of no return? You push past your limits and open up new terrains of possibility. Each challenge accepted leads to greater ability when you confront the next. Taking the first step off the Hill of B, leaving the easy and comfortable knowledge there to pursue mastery on the Hill of A is a point of no return. Forcing yourself to ask the question this week that you were too shy to ask last week is a point of no return. When you take that step, you know that tough times lie ahead in the Valley of C. Those who cannot bring themselves to take that step confine themselves to the path of least resistance. A leadership disposition guides you to take the path of most resistance and turn it into the path of least resistance.

LRN is headquartered a few miles from the Pacific Ocean in Los Angeles, and since I started the company in 1994, I have worked hard to personally recruit the most talented people I could find. Inevitably, when I identify and pursue a potential recruit who lives in another city, we end up in a pros-and-cons-type debate about the relative merits of wherever they live and Los Angeles. Each time I have this discussion, it sounds eerily the same. Their city has great culture, my city has great culture; their city has great restaurants, my city has great restaurants; and back and forth we go in this ledger of pluses and minuses. But in the end, when all has been tallied, I play my trump card. "Both cities are great," I say, "but all else being equal, my city gets an extra boost, because in Los Angeles we have the sun, and the sun is that one thing that shines through all the other qualities, making them that much better." In business, that is what passion does. Passion is like the sun shining through everything; it makes it that much better.

Passion is the difference between a morning wake-me-up and a global corporation. Starbucks chairman Howard Schultz makes a good cup of coffee, but he is passionate about creating a workplace full of dignity and respect for his employees, customers, and suppliers. Schultz's passion wafts through the company and its many shops like the scent of roasting coffee beans, inspiring everyone who catches a whiff. And that makes all the difference in the world.

"You either have a tremendous love for what you do, and passion for it, or you don't," Schultz told BusinessWeek. "So whether I'm talking to a barista, a customer, or an investor, I really communicate how I feel about our company, our mission, and our values. It's our collective passion that provides a competitive advantage in the marketplace because we love what we do and we're inspired to do it better. When you're around people who share a collective passion around a common purpose, there's no telling what you can do."[254]

You need passion to start a Wave. You've got to turn to the person to your right and have real conviction that if we make this Wave we can help our team win. If you're not passionate about that, then it will never happen. Without passion, you grow complacent, and complacency leads nowhere. "Passion is everything," Steve Wynn told me. "It springs from strange places in the human psyche, from a kind of introspective, deep, and penetrating consideration of what you do, and it unleashes a phenomenal amount of energy that leads to higher insights and a deeper understanding of your customers or your employees. And it strikes a happy, deep, self-satisfying chord. It resonates. And when it does, you're off on a hunt. You don't think that you're tired or even working. You're just consumed with the notion that if you can get this done, it's significant; it's wonderful, and off you go. That's the thing we call passion."

You can express your passion in any way you want. You can write an e-mail with passion, you can speak with passion, or you can create a spreadsheet with passion. Passion is the spice that enhances all other ingredients with greatness. Some people express their passion by just showing up, every day, on time, steady as a rock. Passion fuels enlistment and alignment and communication. Have you ever been truly persuaded by an argument that wasn't put forward passionately? Passion is the sun, and leaders are passionate. "You take two runners," Massimo Ferragamo told me, "one with an incredible physique and the other who runs with passion, and the second one you know will win even if it kills him. Working with passion is an engine that is unbelievable. A person with drive and passion does three times the job of another person. But it is not so much the quantity of the job; that is not the point. The point is that they draw crowds; they have followers; they push, and lead, and so achieve much more."[255]

Optimism lives hand in hand with passion. Would the United States have spent 10 years trying to land on the moon if we believed there was a chance we would take off and miss? "I am an optimist," Sir Winston Churchill once said. "It does not seem too much use being anything else."[256] Self-governing people don't allow themselves to entertain the notion of not landing on the moon. They don't keep the vote in their mind to say, "I choose success versus failure." They only envision how they are going to land on the moon. They've got that positive, passionate energy.

That last thought may seem—well—optimistic. But there is an important power lurking in optimism, the power of unlimited belief. Pessimists hold limited beliefs. The doubt and fear of failure that are natural to everyone trying to achieve something great creeps into their brains and ossifies there, creating friction and dissonance and bottling up the amazing power that brains can unleash when filled with belief. The only way to get to the next level, to reach the point of no return and to push past it, is to spend zero time contemplating the alternative. "Perpetual optimism is a force multiplier," said former U.S. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Colin Powell.[257] Helen Keller, who had vision greater than eyesight and was no stranger to the point of no return, said, "No pessimist ever discovered the secrets of the stars, or sailed to an uncharted land, or opened a new heaven to the human spirit."[258]

When Bill Gates was in high school, he and his friends would sit around marveling at what they thought was the undeniable future. "We couldn't believe that everyone else didn't see what we saw," he said in a recent television interview, "that personal computers were going to change the world." This was long before the fateful meeting with IBM when Gates and Paul Allen realized that if they just had an operating system, they could change the world (so they went out and bought one, which they resold to IBM, and Microsoft was born).

It's virtually impossible to be inspired and generate passion unless you have an important mission. The journey to self-governance is inspired by the pursuit of significance. Leaders believe that landing on the moon will benefit mankind, not just profit the company. Leaders believe in ideas. I founded LRN on the idea that the world would be a better place if more people did the right thing. Leaders think of themselves as cathedral builders, not bricklayers. Mission, whether personal or organizational, needs to be important, something worthy of your inspiration or your passion. It could be number two on your list or it could be number three, but it's got to be on your list of important things. You will never find enduring, self-perpetuating power by pursuing the mundane. Passion and optimism compel those who assume a leadership disposition to engage in enterprises of transcendental importance.

Significance means different things at different stages of your life. The young, for instance, often have less time and resources to devote to giving back to their community than those who are older and more established in life. The most successful among us might feel that our achievements alone add up to a life of significance. But the pursuit of significance I am talking about is a disposition toward serving others, toward devoting some measure of every stage of your life to improving lives. Even the most successful need to always measure their efforts against the higher standard of service to others. To make that shift, to envision your efforts in service of a better world, creates a disposition that leads you beyond the immediate and mundane toward the extraordinary and exceptional. If you can pursue significance in this way, then, and only then, can you achieve true success.

And so we have circumnavigated the lens of how and returned to where we began, envisioning a better future through the pursuit of significance. And so we go around again.

Like a ship's sextant aimed at the stars, this lens—the Leadership Framework—can help you navigate your way through a world of how. By developing a leadership disposition and focusing your efforts and perspectives on the areas we have discussed, you will begin to fill the synapses around you with trust, alignment, transparency, inspiration, and passion. You will begin to make Waves, perhaps little ones at first, but their effects will be immediate and long lasting. More than just a way of seeing, the Leadership Framework has all the qualities I have tried to put in this book: It is a system whose many parts are mutually reinforcing; it is a framework of ideas on which you can build structures of understanding; it is a constitution, informed and driven by a values-based approach to the world; and it is steeped deeply in the notion of self-governance, the thought that ultimate success will never come from without, but rather from within.

As the Leadership Framework circles back on itself, so too now does this book. We began our journey together with the story of Krazy George Henderson and the first Wave, and if you flip back now to that first story and reread George's description of that fateful day, you will see that without consciously knowing it, George was as alive to the ideas of the world of how and the Leadership Framework as you now are. He knew that there was a way of pursuing his goals—a set of hows—that was more powerful, more effective, more self-sustaining, and more significant than other ways. I would reprint that story for you here, but it is probably easier for you to just flip back to the Prologue and read it again.

Besides, everything has to end somewhere.