CHAPTER 5

Leveraging Cultural and Political Authority

CRAFTING BRAND STRATEGY requires stepping back to view the brand as a strategic asset. The economic value of a brand—its brand equity—is based on the future earnings stream the brand is expected to generate from customers’ loyalty, which is revealed in their willingness to pay price premiums compared with otherwise equivalent products. Managing this income stream into the future requires a sophisticated understanding of how the brand has acquired its current value.

In the mind-share model, brand equity is based on the strength and distinctiveness of brand associations. The brand essence, lodged in the consumer’s mind, is its source of equity. The more firmly rooted, the stronger the brand.1

In the viral model, brand equity is located in the brand’s hold on influential people. Brands well entrenched among the most influential and fashionable people have high equity. Managing equity in this model involves the precarious business of continually ingratiating the brand into the short list of the most fashion-forward set.

How should we understand an iconic brand as an asset? And how should we deploy this asset to enhance its value? For iconic brands, the brand is a symbol so equity is a collective phenomenon, rather than a product of the brand’s hold on individual consumers. The success of a brand’s prior myths establishes a reputation. The brand becomes renowned for telling certain kinds of stories that are useful in addressing certain social desires and anxieties. In formal terms, from the brand’s prior myths grow two kinds of assets—cultural authority and political authority. Identity brands succeed when their managers draw on these two types of authority to reinvent the brand’s myth. I will use a genealogy of Budweiser to develop this cultural model of brand equity.

Budweiser Genealogy

Few companies have responded as deftly to American cultural changes as Anheuser-Busch. Yet, for much of the 1990s, the company’s flagship brand, Budweiser, was in a tailspin. Since iconic brands earn their keep by creating mythic resolutions to societal contradictions, when these contradictions shift, the brand must revise its myth to remain vital. Budweiser faced just this situation in the early 1990s. Bud had soared in the 1980s with “This Bud’s for You,” one of the decade’s most influential myths. Yet the branding began to misfire around 1990, and Bud went into a seven-year funk. Anheuser-Busch struggled to recover from this disruption with various mind-share strategies and failed each time. Budweiser finally recovered its iconic value with two overlapping campaigns—”Lizards” and “Whassup?!”—which together created a new Bud myth that spoke precisely to the social tensions of the 1990s.

The financial results were impressive. From 1997 to 2002, Anheuser-Busch’s operating margins climbed from about 18 percent to nearly 24 percent, and Wall Street responded with enthusiasm, bidding up the stock by 140 percent in a five-year period during which the Standard & Poor’s 500 index was flat. Bud’s branding efforts increased the perceived value of the brand, protecting sales as Anheuser-Busch aggressively pushed Bud pricing from an historic low in real dollars to price points that approached the major import rivals.2

Anheuser-Busch rolled out Budweiser to national markets at the beginning of the twentieth century, one of the earliest beers to do so, and began advertising Bud extensively in national magazines. By the 1950s, Bud was crafting a myth that encouraged working men to share in America’s new idyllic life of suburban leisure. Budweiser ads showed men how good times were to be had with their family and friends in leisurely activities. With this advertising, Bud became the best-selling beer in the United States. But the brand’s leadership would soon be challenged by Schlitz and upstart Miller High Life. We pick up the brand genealogy in the 1970s, as Bud’s postwar myth fell apart in the face of Vietnam protests, economic decline, and Watergate.

Beers Battle with Reactionary Manhood Myths

Like Mountain Dew and Volkswagen, Budweiser also stumbled when it hit the cultural disruption of the late 1960s. Budweiser’s myth of the suburban good life was wiped out by a laundry list of devastating national failures. Massive urban protests and civil disobedience demonstrated that the postwar good life was not very good for African Americans. Japanese corporations began to prove that American companies were no longer world leaders in major product categories. The Arab oil cartel showed that U.S. economic power was much more fragile than previously understood. The Viet Cong made the Pentagon’s technical superiority a moot point. Watergate undermined Americans’ confidence in their political system. And the burgeoning women’s movement threatened the traditional male role as head of the family.

Many middle-class American men, particularly on the coasts, gave up on the idea of the American empire and took up the cultural revolution. They embraced a loosening of social mores and equality for women and African Americans.

However, the response in so-called Middle America—what Richard Nixon would famously call the silent majority—was quite different. In particular, white working-class men became attracted to aggressively masculine ideals that defensively proclaimed men’s power in the face of U.S. economic and political decline. These men experienced America’s difficulties and the rising influence of women as a crisis of manhood, a loss of control that produced considerable anxiety. Many of these men felt that the nation was becoming too feminine.

The beer market was particularly swift to respond to these emerging sentiments, as the core drinker was male and working class. Budweiser, Miller (with its “Miller Time” campaign), and Schlitz (with its swarthy adventurers in its “When You’re Out of Schlitz, You’re Out of Beer” campaign) all battled fiercely to create a new American myth that would respond to the desires of these men to regain a sense of masculine power.3 Budweiser ditched the leisurely beer-swilling scenes portraying men at home, with friends at dinner parties, and in pool halls. Instead, Bud was now was the chest-swelling “King of Beers,” and daredevil race-car drivers and marching band music celebrated Bud as a champion and encouraged the beer’s drinkers to likewise think of themselves as kings.

Budweiser offered up the company itself as a role model for men who yearned for the return of U.S. military and economic might, and the return of the man as the king of his family. Ads declared over and over, simply, that Bud was “The King of Beers.” Anheuser-Busch said, in effect, “Look at us as a model! We’re successful and here’s our secret: We have the winning attitude. While the government, the military, and other companies may be failing to meet your ideals of manhood, Bud is doing great!” Anheuser-Busch had the winner’s spirit and, to prove it, used the highest-quality ingredients and the most labor-intensive and expensive processes because the product had to be perfect. Anyone who approached life with this spirit was a winner, a king. Bud drinkers, of course, were the first in line to be so ennobled.

This chest-puffing myth kept Bud in the hunt, but did not stand out against myths offered by Schlitz and Miller. It wasn’t until Budweiser swiped Miller’s work-reward concept and did it one better that Bud soared to iconic status.

“This Bud’s for You”

Budweiser’s climb to iconic stature was made possible by the new American ideology championed by Ronald Reagan. The Unites States bottomed out in the late 1970s: Inflation hit double digits; then, a deep recession resulting from inflation-correcting measures sent unemployment soaring. Japanese companies continued to make inroads, and the United States suffered through the embarrassment of the year-long wait to rescue American hostages trapped in the Iranian embassy. Cultural tensions ran at feverish levels, especially for men. Demand swelled for new national myths that would inspire the country to return to its former glory. And answering that call, along with the films and television programs of the day, was Ronald Reagan.

Reagan connected with men of all classes when he called for the United States to return to its roots as a frontier nation. He revived the idea of the man of action, calling out for American men to emulate John Wayne’s portrayals of frontiersmen in Western films, as well as the modern frontiersmen like Clint Eastwood’s Dirty Harry and Sylvester Stallone’s Rambo. The United States needed new man-of-action heroes: individuals with the vision, the guts, and a can-do spirit to transform its wobbly institutions, invent wildly creative products, build fantastic new markets, and conquer distant infidels. Reagan presented himself as a modern-day man of action who stood up to government bureaucracies and the communist threat. As Reagan went after Mu‘ammar al-Gadhafi, Manuel Noriega, the Sandinistas, and the Soviet Union, American men of all classes rallied around his heroic vision, forging a historic shift in the electorate. Inspired by his call to arms, white working men, many of them lifelong Democrats, shifted their allegiance to Reagan.

Managers and professionals interpreted Reagan’s call for men of action in terms of the new “gold rushes” on Wall Street, in Texas oil country, and in the high-tech corridors of Silicon Valley and Boston. Cutthroat, individualistic competition was now admired and the quest to make money reigned supreme.

Working-class American men responded to this call more collectively. Reagan’s manifesto was understood as a nationalist call to reverse the deterioration of domestic industry, to restore U.S. power through the collective efforts of American men rallying around a national cause. These men heard a call to war, but an economic war rather than a military one. Many working men blamed the disappearance of industrial work on aggressive competition from abroad. Japan especially had more efficient industrial production and was aggressively taking share in the United States. Consequently, American men were told they had to push their game up a notch. Reagan, Lee Iacocca, and other business and political leaders challenged them to help restore U.S. might with renewed vigor and sacrifice for their country. For the most part, men heeded these battle cries. “Buy American” bumper stickers appeared from coast to coast.

Yet even as workers rallied to this national project, many large corporations continued to aggressively ship production jobs to locations overseas, where wages were lower, and to substitute technology for labor. American workers wanted desperately to believe in a resurgent United States that relied on their labor, but they were faced with considerable evidence that corporate America had other intentions. This contradiction between Reagan’s new ideology and the actual state of working-class jobs produced an enormous demand for new myths.

Myth Treatment: Working Men are Men-of-Action Artisans

Budweiser picked up Reagan’s battle cry from the point of view of working-class men, many of whom were being laid off, forced to take sizable wage and benefits cuts, or were being pushed into the low-wage service economy. Adopting the persona of a powerful leader, Bud lauded workers for their heroic efforts and exhorted them to approach their jobs with the right values.

In the launch spot, “This Bud’s for You,” the narrator patted workers on the back: “To everyone who puts in a hard day’s work, this Bud’s for you.” The jingle, a peppy pop salute, fleshed out the narrator’s proposition.

This Bud’s for you.

There’s no one else who does it quite the way you do.

So here’s to you.

You know it isn’t what you say, it’s what you do.

For all you do, the king of beers is coming through.

The ad paraded a collage of blue-collar workers from all walks of life, each of whom practiced his trade with consummate skill and enthusiasm. Viewers saw train conductors, lumberjacks, construction workers, truck drivers, farmers, cooks, fishermen, welders, window washers, a boxer, a barber, a produce hauler, a meat cutter, and a policeman. In a scene borrowed from Sylvester Stallone’s Rocky, a butcher used a cow carcass as a punching bag. Bud championed every man—race, region, and age were all irrelevant—who worked with his hands. The working men were all pictured as determined guys who loved their jobs and approached work with can-do attitudes.

As the campaign developed, the jingles became ever more encouraging, sometimes lapsing into cornball sentiment: “You are the power, the man of the hour, you really get things going,” and “You keep America going, you keep the juices flowing, you are muscle, the hope and the hustle, you keep the country growing.” But Bud was adamant about whose side the brand supported. Bud saluted men who industriously pursued work as an intrinsically satisfying calling, men who applied their craft skills with good humor and determination. The result was that America “worked,” and work made the man. Bud implied that when working men participated in American enterprise together, the country would hum. Reveling in their contributions, working men formed a heroic brotherhood, gathering with other men in friendship and solidarity at the end of a working day. Bud gave men hope for a revival in the centrality of skilled manual labor.

Budweiser’s myth treatment can be summarized as follows: Working men are men of action too, artisans whose talents and gung-ho spirit are crucial for America’s comeback. Budweiser salutes these men by painting portraits of their industry and skill, revealing that these “back stage” jobs play a central economic role.

Authentic Populist Voice: Skilled Artisans

Bud’s vision of work directly opposed the economic realities of the times. America was becoming a postindustrial society as technological advances and global outsourcing made many industrial production jobs obsolete. Bud used television ads as a bully pulpit to argue that the old guild ideals of craft labor still existed and could be revived. To make the work supremely important, Bud dramatized projects in which men labored industriously in backstage skilled crafts that, we learned, supported cities, sports teams, and the nation:

- A bicycle craftsman who built custom bikes for the U.S. Olympic team because “You can’t build a bike for the Olympics by machine. Each tube has to be custom fit, to transfer weight and forward momentum. After all, a champion should ride a champion.”

- The welders and riveters who worked on scaffolding surrounding the Statue of Liberty: “This Bud’s for the crew restoring America’s pride in liberty.”

- The workers in a failing industrial city who overcame adversity and put together a plan to bring the city back to life. “They said this city was through. You said, ‘No way!’”

- An African American baseball umpire who worked his way through the minor leagues. When he was promoted to the major leagues, he had to stand his ground against an angry veteran manager who contested the ump’s call. In the end, the umpire earned the manager’s respect and together they enjoyed a postgame Bud.

Bud championed a revival of artisan work and the heroic pursuit of challenging collective projects. To build optimism that this kind of work could again flourish, Bud celebrated occupational pockets where these values still existed. In these populist worlds, which harked back to the previous century, before the rise of mass production, workers still earned tremendous respect because they pursued their labor with skill, selfless dedication, and enthusiasm. These men were heroes because they were absolutely committed to getting the job done right in order to contribute to America’s health. Bud could credibly champion this salt-of-the-earth myth on the basis of a long-term demonstration of fidelity by the parent company, Anheuser-Busch. Throughout the 1970s, Anheuser-Busch had asserted its commitment to the brewing craft as a family-owned company, with each generation of Busches dedicated to brewing as an art, using a team of Clydesdale horses as a symbol of this heritage. In unspoken opposition to its arch rival Miller Brewing Company—owned by Philip Morris to diversify its portfolio—Anheuser-Busch asserted that the huge company was in reality a family of craft brewers. Ads showed members of the Busch clan, narrating the history of the company with black-and-white photos, proudly documenting the brewing process, and lecturing the audience on the right way to pour a beer. Throughout the 1980s, Anheuser-Busch ads reminded the audience that Budweiser was made by artisans, no different really than its beer-quaffing constituents. The Busch men stood for the same values as did America’s working men, because they, too, were craftsmen.

Charismatic Aesthetic: Epic Films

“This Bud’s for You” used an epic film style to make seemingly mundane work heroic. This gravitas was enhanced by the announcer’s voice, a slow deep baritone, reminiscent of NFL Films’ football highlights. And the camera admired the workers from below, framing them as larger than life. Seemingly mundane work—building a bike, sanding metal, calling balls and strikes—was portrayed as a life-or-death drama.

Through the narrator’s voice, Bud spoke—much as a boss would—with almighty authority to extol the work of Bud drinkers. This persona was crucial. In effect, Bud replaced the voice of corporate America, which at the time showed little interest in workers’ skills and instead was exacting wage concessions and downsizing. In the Bud myth, workers finally get a boss who respected their contributions, who understood labor’s value, and who distributed praise appropriately.

In an economy rapidly moving from industrial to service jobs, “This Bud’s for You” connected powerfully with working men. And these workers rewarded the brand by making it a valued component of the symbolic armor with which they faced work-place uncertainties. The campaign firmly established Budweiser as an icon, one of the most persuasive and cherished cultural leaders of America’s working men.

Cultural Disruption: Cynicism to Downsizing

By the late 1980s, American companies were reasserting a dominant position in the global marketplace. Workers had accepted difficult sacrifices in the process: lower pay, longer hours, and tougher production benchmarks. “Neutron” Jack Welch had furloughed fully 25 percent of the General Electric work force, over 100,000 workers. Earnings for nonmanagement workers declined by more than 10 percent in real terms.4

So when the economy finally began to perform well and productivity advanced past key rivals Germany and Japan, American workers expected repayment for the sacrifices they’d made over the previous decade. What they found instead was even more aggressive labor rationalization under the aegis of reengineering. Rather than settle back into a paternal model that gave workers a secure livelihood, American CEOs—motivated now with sizable stock options to do whatever it took to increase stock prices—squeezed even more productivity from their organizations. The result was a decade in which the rationalization of all corporate expenses—through technology investments, process engineering, and outsourcing to secondary labor markets—became a primary driver of corporate profit growth.

With the recession and jobless recovery of the early 1990s, nonprofessional men finally lost faith and rapidly abandoned their belief that their work would ever return to the respected, secure calling that they dreamed of. Bud’s heroic artisan myth was shattered once and for all. Populist politics surged.

Anheuser-Busch was slow to respond to this tectonic shift. Instead, the company dragged out all the old symbols in a bet-the-farm run to revive the collective work-centered ideals of manhood. “Made in America” juxtaposed images of a bald eagle flying above Niagara Falls, Clydesdales running in slow motion, military men, and an American Olympic champion on the awards stand. Amazingly, the Bud narrator acknowledged the beleaguered state of American workers:

If I thought that no one cared about the things I do in life, I’d still care about working hard and making it turn out right. Made in America, that means a lot to me. I believe in America, and American quality. Here’s to you America, my best I give to you.

Bud used the ad as a confessional: Corporate America no longer cared about its workers, and it was pointless to pretend otherwise. Nonetheless, men of honor should continue to work hard because they’re patriotic. Perhaps Anheuser-Busch thought that the Gulf War provided enough cover to stir such sentiment, but lauding “Made in America” seemed only to remind Bud drinkers of the jobs that were continuing to move overseas. The growing cohort of Wal-Mart shelf stockers could only grimace.

Failed Experiments with Conventional Branding

As the artisan myth lost traction, Anheuser-Busch began to experiment with replacements. For seven years, the brand team struggled to locate a resonant, new advertising campaign. Rather than reinvent Bud’s myth, though, the brand team reverted to conventional mind share and viral branding models. The team generated a wide variety of creative ideas that worked through every trick in the branding book, only to come up empty each time.

Brand Essence. The brand team first pinned its hopes on a campaign called “Nothing Beats a Bud,” which abandoned the epic dramas of American work and instead tried to revive Bud’s branding from the 1970s. The ads presented a generic montage of “typical” American scenes: jogging in a small town, a barber shop, a college girl waving her diploma, young men in military uniform, a guy washing his car and making a muscle, some cowboys, guys watching a ball game on TV, a deaf woman talking in sign language, a woman blowing a kiss, a woman wrapped around a guy, and, of course, a few seconds of the indefatigable Clydesdales. This patchwork quilt of Americana was intended to communicate Bud’s brand essence as a quintessential American masculine classic. The chest-beating lyrics harked back to the 1970s:

Here’s to you America, for being strong, for coming through.

Doing all that you can do. We send our best to you.

Nothing beats our best, Budweiser.

Nothing beats a Bud.

And we’ll toast and cheer with the king of beers,

Nothing beats a Bud.

I’ve seen ’em come and go. I’ve seen enough to know.

So let your colors show. Nothing beats our best.

Nothing beats a Bud . . .

(America’s Best)

Brand Essence Again. A second campaign attempted the same idea, rekindling Bud’s DNA, but with different (and better) creative. Because of the brand’s success among American working men, Budweiser’s dominant associations included “American,” “masculine,” “classic,” and “for working guys.” So, in “It’s Always Been True, This Bud’s for You,” the brand team presented Bud as an American classic for real guys. One ad used a jingle to tell the audience that Bud was as classic and familiar to Americans as blue jeans, baseball, and beautiful blondes (imitating a famous Chevrolet campaign of the 1980s, but leaving out the apple pie). Another spot was set in a car garage, where some guys were working on their old, collectible cars. They held a verbal sparring match, arguing about the most classic make and model of all time. Budweiser, the audience was left to believe, was right up there in the pantheon.

Other Category Benefits: Sex Potion. While Bud was sinking, other brands were more successful selling beer as a sex potion for men. Budweiser tried co-opting this aspiration from its competitors with a variety of “Bud makes guy’s dreams of babes come true” ads. One infamous spot showed two cool guys decked out in shorts and shades, imitating the feature film Risky Business, on a desert hike. When one guy opened a briefcase, a pool scene rolled out and inflated itself, complete with Buds and a young woman in a bathing suit. In a different ad, another cool guy unrolled a towel to reveal three more beautiful women in swimsuits. Viewed side by side from above, their swimsuits formed a perfectly rendered Bud logo.

Coolhunt. Other ads sought to make Bud relevant by weaving the brand into trendy pop culture currents. This strained effort involved a series of ads that traded on an odd juxtaposition: African American rap music and Bud. In “Auction,” a touring rap group’s bus got a flat tire “a jillion miles outside the ’hood,” in the rural Midwest. The hip-hop-geared musicians worked their way through a cornfield in search of help and stumbled on a group of farmers at an animal auction. Deciding that the auctioneer “knows how to sell but’s got no beat,” the rappers took over. The lights dimmed, the turntables came out, and the group rapped the typical auction patter to the beat of record scratches. The spot ended with a rap shout-out: “Yo! MC Cowseller! Bud! Fresh!”

Buzz. Finally, Anheuser-Busch fired D’Arcy, Budweiser’s agency of record for over three decades, and handed the business to DDB–Chicago, which had been doing breakthrough work on Bud Light. Ironically, the last ad that D’Arcy made before losing the account was the first ad in many years that attracted any attention. Set outside a log cabin tavern in the middle of a dark swamp, “Frogs” featured three mechanical frogs that croaked as crickets chirped in the background. While the audience waited for the action to unfold, the croaking became a promotion for the sponsor. The frogs were croaking the syllables, “Bud,” “weis,” and “er.”

DDB picked up the concept and made a string of frog ads that audiences at least valued as entertainment and liked to talk about. It was a cute, one-hit joke, and the frogs got their share of laughs. Unfortunately, the ads did little to build Bud’s identity value. DDB tried to extend the concept with ants that partied with Bud and a mischievous lobster that stole beer, but like “Frogs,” these ideas also failed to perform significant branding work. The word of mouth failed to do much to the value of bottles of Budweiser beer.

“Lizards”

While Anheuser-Busch was trying in vain to revive Bud using conventional branding formulas, an enormous new slacker myth market had emerged, as described in the Mountain Dew genealogy. Budweiser’s recovery was premised on inventing a new slacker myth that spoke to men who had become intensely cynical about the idea that their manhood hinged on putting in a hard day’s work.

Lizards Myth Treatment

Budweiser’s “Lizards” campaign was one of the decade’s most effective and durable branding efforts. The ads were televised for four years and continued for years as a series of radio spots. The creative idea behind “Lizards” was deceptively simple. Anheuser-Busch had been running the “Frogs” campaign for two years. To extend this campaign, Anheuser-Busch selected work from another ad agency in their stable, Goodby Silverstein & Partners. Goodby came up with an improbable concept: a jealous lizard who lived in the swamp wanted to rid the swamp of the celebrity frogs. The would-be assassin, Louie, hung out with his lizard friend, Frankie, on the perimeter of the frogs’ swamp and commiserated. Louie wanted to star in the Bud ads and seemed ready to try anything to get his chance to step over the rival frogs. Frankie was the street-smart and world-weary friend who consoled Louie and tried to keep Louie’s zealous ambitions in check.

All the action centered on these two alleged spectators who observed, and tangentially participated in, what transpired around them. Like Seinfeld, the campaign made a lot out of little real activity. Moreover, “Lizards,” again mimicking shows like Seinfeld, was entirely reflexive: The ads were about how the advertising was made.

The “Lizards” ads were dead-on funny. But rather than the mindless silliness of the “Frogs” campaign, the humor was much more effective in terms of branding because it relied on wicked satires about working life. To understand how the satires worked, we have to dissect the ads to reveal the premises that the ads twisted for laughs.

The plots revolved around Louie’s intense envy for the frogs’ stardom and his quixotic mission to replace them. In his banter with Frankie, Louie resented the three Bud-weis-er frogs for having been cast in the ads, for becoming stars, and for their big salaries:

Louie: I can’t believe they went with the frogs! Our audition was flawless. We did the look [postures for the camera]. We did the tongue thing [sticks out tongue].

Frankie: Frogs sell beer. That’s it. The number one rule of marketing.

Louie: The Budweiser Lizards. We coulda been huge.

Frankie: There’ll be other auditions.

Louie: Oh, yeah. For what? This was Budweiser, buddy. This was big. Those frogs are gonna pay.

Frankie: Let it go, Louie. Let it go.

Louie was so jealous that he fantasized about the frogs’ assassination. In a spot shown during the Super Bowl, Louie hired a ferret to cut the support for the electric Budweiser sign that hung over the bar’s entrance. As the ferret climbed the sign, Louie watched, secretly hoping the ferret was up to the task of sabotaging the sign and electrocuting the frogs. “I’m no electrician but that has got to be dangerous,” Louie said with transparently fake concern. When the sign fell and sent a charge of electricity through the swamp, the frogs smoked and sizzled from the shock. It seemed that Louie’s dreams were finally fulfilled. “Frankie, eventually every frog has got to croak,” he intoned with a smirk. Unfortunately, the frogs proved hardy enough to survive the assassination attempt. In turn, the distraught Louie could only construct uglier plots to rid himself of the frogs and to steal their limelight.

To Louie’s chagrin, Anheuser-Busch hired the ferret as a spokesperson, even though he could only screech gibberish. Exasperated, Louie condemned the ferret for his obvious lack of qualifications. Frankie, forever pushing Louie’s many buttons, suggested that the ferret possessed star potential. Sporting a beret, the ferret looked, according to Frankie, “like a famous French director.” Louie was beside himself.

Years into the campaign, Louie finally made it as a replacement for one of the frogs. But, even then, Louie wasn’t the big cheese. The frogs revealed that they were actually tough guys who could talk, and proceeded to lash Louie with their long frog tongues, repaying him for the years he spent taunting them.

In the culmination of Louie’s tragic quest for vainglory, he ran for president of the swamp. But he was up against a Kennedy-esque turtle who’d concocted an impressive platform, complete with a smear campaign that featured ads about Louie’s seedy past. Louie lost the election and once more had to endure the pain of sitting on his branch and watching other mechanical beasts bask in power and fame.

Louie was the voice of the working man who’d allowed himself to be seduced by the new hypercompetitive U.S. labor market, where the winners became celebrities. He ached to get a piece of the action that he saw emanating from economic and cultural hot spots like Los Angeles; Silicon Valley; Washington, D.C.; and New York City. All that he attained, however, were equal doses of neuroses and self-absorption.

Frankie countered Louie with the slacker ethos, cool and aloof. He was happy to hang out in his back yard, the swamp, and take cynical swipes at the world beyond. Frankie understood how the game worked. He was unwilling to get sucked into a game he knew he probably could not win. The gates to fame and money were closed, so why bother? Ultimately, the only reasonable choice was to hang out on the sidelines and watch the proceedings as a spectator, emotionally distanced from the game.

Louie’s passive-aggressive behavior wonderfully tapped the new zeitgeist of men who had trouble seeing causal relationships between hard work, dedication to craft, and society’s respect. They sympathized with Louie’s efforts to succeed in the new system and felt his pain when he failed time and again. That Louie couldn’t resist stardom’s temptations made for tragic comedy. But, in the end, they knew that Frankie was right. They delighted in Frankie’s cynical worldview: better to sit on the sidelines, take it easy, and have a laugh. A guy could attain slacker manhood by asserting his sovereign prerogative to not participate, to reject the game’s premises outright.

“Lizards” grabbed the audience because it used satire to make American men confront an idea that was hard to face straight on. Giving up on old models of manhood, these guys were still grasping for alternative toeholds. “Lizards” revealed a simple truth: You’re not a hero, because society won’t let you be. So what? The pressure’s off. Revel in the absurdity of your situation! Sit back and enjoy.

The myth treatment for the “Lizards” campaign can be summarized as follows: Today only suckers strive for respect by chasing the American Dream, climbing the ladder of success. Now the only real option is for men to opt out of these man-of-action games and, instead, enjoy the show by mocking those who are conned into competing for success.

Charismatic Aesthetic: Borscht Belt Comedians in a Kid’s Cartoon

“Lizards” was social satire. Like much great satire, the campaign was set in another place and another time so that the story could poke at cherished beliefs without alienating the audience. The set design and mechanical animals, lifted from the “Frogs” ads, reminded the viewer of a Disney-Pixar flick rather than an ad. Yet the lizards were nothing like swamp creatures. Their patter evoked something like Borscht Belt comedians trading one-liners or old Italian guys in the Bronx sitting on their front stoop commiserating.

By displacing the barbed lines, putting them in the bodies of mechanical lizards whose mouths were imperfectly synched to open and close to the match their words, Bud coaxed the audience to entertain otherwise taboo thoughts. These silly mechanical creatures were allowed to voice truths that were painful and deeply personal.

Authenticity Among Immigrant Enclaves

The campaign drew on the populist world of the immigrant enclave, a place far removed from the norms of the middle-class labor market. The choice was original and compelling. But how did Budweiser get away with this point of view after years of corporate cheerleading?

Populist authenticity can be garnered from the literacy with which one speaks from the populist world, and the fidelity with which one stays true to its values over time. At the time, Budweiser lacked the authority to champion the immigrant’s cynical views. After all, Bud’s earned its iconic value by motivating men to keep up the good fight, working hard for their company and country. So to switch sides, to move from a myth that celebrated hard work to one that mocked it, required not only that Bud deliver performances off the scale on authenticity, but Bud also had to be contrite, renouncing its old views. “Lizards” seemed like masochistic advertising. The ads seemed to go of their way to slam Anheuser-Busch’s hard-won reputation. By conventional standards, the campaign’s irreverent treatment of the firm was incoherent. Louie continually ridiculed the marketing decisions of Anheuser-Busch management: “Do you hear the script they wrote? Bud-weis-er. How creative! These advertising people just don’t get it.” He made fun of how much Anheuser-Busch spent on the spots. The ads blasphemed virtually everything that Bud had championed for the previous fifty years: the heroic qualities of achieving men, the devotion to hard work and enterprise, the homage to the Anheuser-Busch empire.

The ads even attacked the brand’s other advertising. When the “Whassup ? !” campaign caught on, Louie, true to character, was incredulous. He made fun of the campaign with a tongue-wagging demonstration of his own. Louie even mocked the August Busch III ads, in which the chairman of the board recounted the family history with the brewery. Mimicking August’s unmistakable halting speech pattern, Louie recited the ancestry of the swamp master and the history of the swamp in epic terms.

Many ads have reflexively mocked the commercial conceits of advertising : old Volkswagen ads, the Energizer bunny, Spike Lee’s pleas for Nike, Joe Isuzu, Little Caesar’s, and Sprite’s “Obey Your Thirst,” to name the most prominent. But only the “Lizards” campaign had the audacity to deliver what seemed like a knockout punch to the company that made the product. “Lizards” was an act of flagrant disobedience in which Bud renounced its historic position as the champion of men’s work. Bud gave up the mantle of omnipotent authority—the one that crowned Bud drinkers as kings—for the more humble but more valuable role of slacker confidant. The only way for Bud to credibly switch to this new role was to explicitly distance itself from its previous incarnation.

The Power of Cultural and Political Authority

Iconic brands’ own mythic turf that no other brand can touch. When Johnny-come-lately brands try to invade the storytelling terrain of an iconic brand, consumers summarily reject the newcomer as inauthentic and unoriginal. For years, The Coca-Cola Company’s senior management watched jealously as Mountain Dew grabbed share points for its brands. When the company could stand the situation no longer, it launched Surge in 1996. The copycat soft drink was supported with a clever Leo Burnett campaign that delivered in spades on slacker masculinity allegories and was supported by a huge advertising war chest aimed at male teens. Teenagers flirted with the brand for a while, but soon abandoned it. Surge faded into oblivion in less than two years. The Coca-Cola Company had thrown away hundreds of millions of dollars in a vain attempt to squash its arch rival. Mountain Dew owned the slacker version of the wild man. The authority of the brand was unquestioned. Surge was an interloper with no credibility. Because The Coca-Cola Company did not understand how brand equity works for iconic brands like Mountain Dew, the company mistakenly tried to grab a piece of Mountain Dew’s myth, rather than leapfrog Mountain Dew to chart out a new cultural opportunity.

Mountain Dew’s potent display of its brand equity is typical for iconic brands. Customers will happily stick with their favorite icons, paying a premium even when attractive competitors enter the fray. What gave Mountain Dew such extraordinary traction that its customers so easily resisted Surge? Mountain Dew’s brand equity did not stem from assets identified in typical mind-share models: the ownership of distinctive category associations.5 Rather, iconic brands are valued because customers look to the brand to perform myths that resolve acute anxieties in their lives. Consumers don’t care whether the brand owns adjectives. They care about what the brand accomplishes for their identities. The brand’s equity derives from people’s historic dependency on the brand’s myth. If a brand’s stories have provided identity value before, then people grant the brand authority to tell similar stories later on.

We can only understand how this self-immolation worked to advance Bud’s identity value if we understand the corporation and the brand as two distinct characters in dialogue with the consumer. For many years, Bud and Anheuser-Busch spoke with the same voice: authoritarian, achievement-oriented figures that were proud of their accomplishments and sought to anoint beer drinkers with their power. Now that this model had been discredited among Bud’s constituents, the strategic challenge was how to credibly jettison it and leap to the other side of the political divide.

Anheuser-Busch’s tacit strategy was to allow Bud to run amuck, to attack the father company as would a Bart Simpson type of character. By taking wicked swipes at its own company, Bud joined its constituents who were doing the same. Anheuser-Busch didn’t come out of this exchange beaten up, either. The audience was well aware that this was all a fiction, and the viewers gave Anheuser-Busch credit for this humorous confessional. They respected the company’s willingness to be the butt of the joke, to absorb their hostilities toward the new economy.6

“Whassup?!”

With “Lizards,” Bud rekindled its close identification with working men’s anxieties. The brand had regained its authority by recognizing and responding to the jarring socioeconomic changes faced by its constituents. Frankie’s solution, however—to sit back in the peanut gallery and observe at an aloof distance—lacked a satisfying resolution. Bud still needed a positive myth, an ideal world of manhood around which men could build solidarity. DDB’s “Whassup?!”, a campaign launched to complement “Lizards” in 2000, provided this missing link.

Whassup?! Myth Treatment

“Whassup?!” picked up where “Lizards” left off. The opening salvo in the campaign, a spot called “True,” introduced a new Bud manhood myth into the space created by the “Lizards” satire. “True” was the first chapter of what became an ongoing saga that revealed how a group of childhood friends—African American guys around thirty and apparently single—socialized, how they hung out. The opening shot presented two of the friends, each in his own apartment, drinking Bud from the bottle and watching a game on TV. The action on the television faintly reflected off their faces. In the spirit of the consummate couch potato, each character was hanging out with his game and drinking Bud as a matter of habit.

One of the friends, a man with a large Afro and wearing bib overalls (we’ll call him Bib Man), initiated the phone call to his friend as he slouched deeply in his easy chair. Though dressed in game-day casual, he was clearly a self-supporting, reasonably respectable adult. Bib Man’s friend Ray, a slender man with shaved head and neatly groomed beard, appeared equally entranced—Bud, couch, and televised game—on a weekend afternoon. He answered the phone on the first ring. His performance suggested that while he was not optimistic about the conversation, he would have preferred it if someone called and gave him a reason to live.

The two men exchanged salutations, in the African American vernacular, intended to reveal nothing in particular:

Bib Man: Whassup?!

Ray: Nothing, B. [short for bro, which in turn was originally short for brother].

They admitted that they didn’t have much of anything going on, which probably came as no surprise to most viewers, who could easily intuit from the vibe that this situation was typical.

Ray’s roommate, Jersey Man—he wore a bright yellow football jersey—entered the kitchenette in the background, raised his hands, and delivered an exaggerated “Whassup?!” to Ray, which Ray returned in kind.

At the other end of the phone call, Bib Man couldn’t help hearing the exchange and became suddenly animated, asking cheerfully, “Yo, who’s that?”

In a second, Jersey Man picked up the kitchenette telephone extension, and the three men performed a cycle of joyous “Whassup?!” greetings for each other. Jersey Man interrupted and, inquiring about Bib Man’s roommate, asked, “Where’s Dookie?”

Bib Man responded with a “Yo, Dookie!” and a large, shaved-headed teddy bear of a man sitting at his computer picked up the phone extension. Understated and serious compared to his pals, Dookie appeared to be working diligently. He offered a quiet “Yo.”

Jersey Man shouted the most enthusiastic “Whassup?!” yet, which Dookie rebutted with his own, understated, slightly cool, and extended baritone, “Whassuuuup?!”

The cycle began again, each man delivering his own interpretation of “Whassup?!” into the phone, each man bobbing his head making sure that his tongue hung out in front of his chin as he spoke.

This chorus of “Whassups” had disintegrated into group laughter, when another interruption occurred. The intercom on the kitchen wall next to Jersey Man beeped, and he answered it. The next shot showed a leather-jacketed man standing on the apartment’s stoop and toting a six-pack. He shouted his own stylized “Whassup?!” into the intercom.

The men all charged through one more round of “Whassup?!” which then ended suddenly, like a fire run out of fuel.

Jersey Man hung up and headed to the door to let in the guest with the six-pack. Dookie hung up and returned his attention to the computer screen, and Bib Man and Ray returned exactly to their original state, staring at the game on television. As if the crescendo had never happened, they started over with the same mundane conversation, one they’d probably had hundreds of times.

Bib Man: So, whassup?

Ray: Nuttin’, B. Sittin’ here, watchin’ the game, havin’ a Bud.

Like the earlier exchange, and perhaps countless others, they both nodded and repeated, “True. True.” A black title card with the Bud logo announced the tag line: “True.”

The closing sequence gave the audience access to what was really going on. Bib Man didn’t phone Ray for any particular reason. He simply wanted to share empty time with his friend. The state of doing nothing was a central, and even profound, part of these guys’ lives. It was a way for them to forge intimacy, to express deep affection without saying anything. Nothing needed to be said, because they all experienced the world in the same way, a way they’d built simultaneously through years of hanging out together. The game and the Bud became the firmament, fixtures through which these solidarities flowed.

Subsequent spots established the “Whassup?!” idea as a miniseries, in which, much like Seinfeld and “Lizards” before, not much ever happened. The ads were set in the same apartment, the same camera angles were employed, and the actors wore the same clothes. This was their life. The guys watched sports, drank Bud, and chatted each other up, albeit with precious few words. That all five men could not find anything to fill their time other than to phone each other and practice an in-joke they’d probably done hundreds of times begged the audience to interpret what was going on. More clues were given as the miniseries extended to include episodes in which our Whassup guys collided with people outside their fraternity.

Women Can’t Whassup. In the Whassup world, life revolved around allegiance to the close-knit circle of friends. Whassup was a guys-only club. Girlfriends were barely tolerated, and there was no sign of a wife in any of the spots. All other relationships and commitments deferred to the guys’ elemental bond. Some of the funniest and most strategically effective “Whassup?!” ads took advantage of the tension between guy solidarity and girlfriend desires.

In “Girlfriend,” Dookie snuggled with his girlfriend on the couch. Since they were at her place, the television was tuned to figure skating. The show elicited only a benign stare from Dookie. She, however, was enraptured. She hovered at the brink of tears and clutched his arm as if to brace herself from being overwhelmed by emotion. When the phone rang, Dookie coolly answered it and his pals at the other end of the line all shouted, “Whassup?!” into the phone. The three buddies were at the bar watching a game on television and, missing their fourth wheel, had tracked down Dookie at his girlfriend’s place. Dookie responded with as much enthusiasm as his situation allowed. He turned his head away from his girlfriend, and whispered a “Whassup?!” that he hoped she wouldn’t hear. Unfortunately, his effort stood no chance of convincing his buddies that he was still a member of their club. The buddies knew Dookie was understated, but not this understated.

Sensing that his pals were losing faith in him, Dookie pried his arm from his girlfriend’s grip and turned away from her so that he had a better chance to convince the friends that he was still on their side. He told his friends that he was watching the game and having a Bud. Before his pals had a chance to process Dookie’s words, his girlfriend destroyed his alibi. “Yes, yes!” she squealed as the TV announcer described a skater’s great move. Still looking away from his girlfriend, Dookie grimaced. He did not want to have to explain her noise. At the bar, the friends heard the shrill shriek and, breaking out of their usual bantering slang, inquired seriously, “What game are you watching?” At this point, the guys found it difficult to believe that Dookie was watching the game. Back on the couch, the girlfriend’s high-pitched wail grew more intense. “Yes, yes!” she cried. Dookie could only grimace, keep his mouth shut, and hope that his friends’ misinterpretation kept him out of their doghouse.

The joke worked because the Whassup ritual was a clever way to demonstrate how these friends constantly affirmed their commitments to each other. In many men’s social circles, checking up on an MIA member and hearing a woman squealing “Yes, yes!” in the background would be reason enough for the members to smile knowingly at their comrade’s sexual conquest. In this case, they were only concerned that Dookie wasn’t watching the game they thought he should have been watching. He wanted to finesse his two competing commitments, to have his cake and eat it too. His difficulty gave the audience their laugh.

Similarly, in “Girl Invasion,” the Whassup guys watched an apparently big game. In contrast to their earlier couch-potato routines, they actively rooted during this particular game. Dookie’s girlfriend was perched on one of his massive thighs. When the men erupted into high-fives to celebrate a big play, the girlfriend was accidentally jostled around as though they had forgotten she was there. The intercom buzzed, and when one of the guys answered it, a bunch of women screamed, “Whassup?!” The guys were confused. They’d clearly not expected any more guests, nor had they invited women to watch the game. Each man asked the other if he’d invited anyone, and each responded with a shoulder-shrugging denial. Dookie’s girlfriend grinned coyly. The men groaned. Shamed, Dookie hung his head. Jersey Man stood at the open apartment door as the women charged in, handed him their coats, and squealed like tipsy sorority sisters as they hugged Dookie’s girlfriend.

The next shot showed all of them cramped into the living room, still watching the game. The men’s faces registered grin-and-bear-it expressions of a good day ruined, a feeling no winning team could correct. Standing behind the couch, one of the women pointed at the television and said, “Oooh, he got a big head. Look at his head!” The picture cut to the black screen with the title, “True.” In voice-over, the same woman screeched, “Number thirty-four!” Dookie moaned, defeated, “Oh man.”

Both ads played on the idea that the “Whassup?!” salutation was a passkey into a shared worldview, that it wasn’t a mere catchphrase. Dookie couldn’t shout it out in front of his girlfriend. The idiom was such a complete sign of brotherly solidarity that to use the word in front of her would be totally inappropriate. Likewise, while the guys’ girlfriends could imitate the word, they neither knew about nor cared about the meaning that lurked behind it. Their oblivious, reckless use of the word made the guys cringe. By protecting both how the term was used and its connotations, the men demonstrated that theirs was a boys-only club.

Professionals Can’t Whassup. Likewise, Whassup was a club for working guys, not for professionals and bosses. In Goodby’s contribution to the DDB campaign, “What Are You Doing?” guys who drank imported beers, Heineken in particular, were presented as the antithesis of the Bud ethos. Three satirized men, young Wall Streeters or Silicon Valley professionals, replaced the crew of African American young men. One yuppie was Indian, just back from the club, with tennis racket in hand. He stood in for the new immigrants—from Bombay, Delhi, or even Seoul—who’d joined the nation’s economic elite in droves during the last high-tech expansion. He was incorrigibly cheery. All three wore Ivy League costumes, the clothes that defined preppy in the 1980s: loud plaids, stiff golf shirt collars protruding from beneath yet another shirt, and sweaters, either worn normally or draped around the shoulders.

In sharp contrast to the “True” crew, these men spoke the King’s English and replaced “Whassup?!” with “What are you doing?!” Rather than “watchin’ the game, havin’ a Bud,” the man on the couch was “watching the market recap and drinking an import.” And instead of the hipster-correct “True, true,” response, the yuppies replied to each other with “That is correct, that is correct.” When the Indian man entered the scene from the kitchen, he was told to “pick up the cordless.” When he did, he shouted an enthusiastic “What are you doing?!” with an Indian accent. The shtick unfolded just as it did with the young African Americans, but with hyperbolic versions of the habits and the phrasing of junior executive frat boys. The men were painfully stiff and lacked even a modicum of improvisational skill. They were the Whassup guys’ social opposites.

This parody slammed men who still found identity and solidarity in corporate America. The ad proposed that import drinkers were guys who found fulfillment through their employment and thus devoted all their energies to their professional lives. As a result, they were social misfits; they had no knowledge of, or connection to, popular culture. And because they’d been so heavily socialized in the mechanical interpersonal style of the corporation, they were unable to improvise a conversation. Because they hadn’t a clue about the subtle shades of meaning behind “Whassup?!” they could only parrot it. They treated the phrase like the latest Top 40 radio hit, as a cool fad that they could appropriate to impress each other that they were street savvy. The intense solidarity produced by a few choice slang words proved elusive for professionals whose energies were focused on getting ahead at the office.

The final shot showed two of the original Whassup men sitting on a leather couch. They looked puzzled, even vaguely offended. They’d just watched the same yuppie Bud ad on their television. By laughing at the yuppies with the Whassup crew, viewers could imagine themselves as more interpersonally savvy and graceful than the young professional ciphers. By extension, viewers could feel good about their association with the Whassup guys and their separation from the nation’s elite professional cadre.

Whassup was available only to men who truly shared a brotherly camaraderie, a social bond that could only develop among guys who avoided the instrumental dog-eat-dog work of middle-class occupations to spend “quality time” together hanging out. Although women and professionals desperately wanted to participate in the brotherhood of Whassup, they only understood it as a surface code of slang rather than a deeper intimacy based on years of shared experience. This impenetrability, an exclusion borne of class and gender, formed the core of Whassup’s credibility as a “true” expression of working men’s manhood.

This parable was expanded in a spot called “Wasabi.” Dookie, who emerged as the star of the campaign, was again with his girlfriend, this time at a sushi restaurant. The audience saw only her back. The Japanese waiter presented their food and routinely announced, “Wasabi,” as he placed a small bowl of the green horseradish on their table. With a wry grin Dookie repeated, “Wasabi,” with a touch of the “Whassup?!” delivery style. After the waiter innocently nodded, “Wasabi,” Dookie again repeated the word, this time with more “Whassup?!” gusto, his tongue flapping. The waiter, still blind to Dookie’s playful framing, repeated another innocent, “Wasabi.”

In the background, the sushi bar chefs—stereotypically always eager to shout an incomprehensible phrase in unison—raised their knives and shouted, “Wasabi!” Dookie jumped on this bandwagon, upped the chefs’ enthusiasm, waggled his tongue, and generally played the fool as though he were alone with his Whassup brothers. The cycle repeated, the volume increased, and the camaraderie between Dookie and the Japanese men escalated. And it was all based on improvisation around the silly phrase. Dookie’s girlfriend finally had enough. With her hand, she rapped the table like a judge pounding a gavel, hard enough to bounce the dishes. Dookie snapped to her attention and cut short his boy’s play.

The spot worked by playing on the tension between the natural bonds of working guys championed by Bud, and Dookie’s female relationship. The girlfriend convinced her man to take her out for dinner, finally dragging Dookie away from his Whassup buddies. Yet, even here, among strangers as culturally removed from African American life as one can imagine, Dookie connected in a way that eluded her. She found it neither funny nor worthy of participation.

In clever fashion, “Wasabi” expressed how working men, even strangers, instinctively shared a distinctively masculine intimacy. The bond was based on a shared appreciation for their place in the world, a place in which few words need to be spoken. Additionally, the spot showed that localized pockets of work—in which the joie de vivre of Whassup-styled interaction can be woven into work—still existed. Sushi chefs were craftsmen whose labor was on display for their customers. Instead of the old Bud myth, which celebrated the heroism of craftsmen, the myth in “Wasabi” presented new Bud ideals. Now work was merely an occasion, one of many, in which men could find intimacy in freestyle play.

In the Whassup world, friends created intimacy around their secret code, the different phrasings of a single salutation. The friends knew each other so well that they could practically grunt and groan a generic phrase to communicate everything they needed to say. Different inflections reflected not only men’s different personalities, but a wide range of emotions as the situations demanded. It was a distinctly masculine way of communicating, saying everything by saying not much of anything.

When men had difficulty finding solidarity and affirmation in what they made or in their contributions to society, where were they to look? Whassup provided a humble, yet affirming answer. In this worldview, masculinity needn’t be modeled on the heroic pursuits of soldiers, athletes, cowboys, or even supposedly heroic welders working atop the Statue of Liberty. Manhood lay in the love, loyalty, and intimacy that one shared with one’s mates. Whassup retooled slackers’ scornful mocking into something profound. The ultimate center of gravity for men’s self-esteem flowed from a tightly knit circle of male friends.

The myth treatment for “Whassup!?” can be summarized as follows: Today men find brotherhood and intimacy hanging out together, creating their own hermetic culture that they use to perform for each other. They can’t depend on job success to earn respect, because heroic efforts are no longer rewarded as such. So identity must grow out of the camaraderie of close friends.

Authenticity Among Urban African American Men

Anheuser-Busch set the “Whassup?!” stories in social environs that were virtually the inverse of the prior myth. In “This Bud’s for You,” Bud had championed the heroic efforts of a melting pot of American men who made things happen behind the scenes at work. Bud’s heroes had included the urban, the suburban, and the rural; blacks, whites, and Hispanics; and those in production jobs and those in service jobs. African Americans played a statistical rather than strategic role. In contrast, African American life is the focus of “Whassup?!” Bud’s populist world, recast as the leisurely life of single, urban black men, leaned exclusively on their lifestyle and vernacular for its effectiveness.

The Beats of the 1950s had built their aesthetic around worship of the raw sensuality and stylish sensibility of the inner-city black hipster. Since that time, the African American ghetto, and particularly the single, urban black man, has been one of the most potent populist worlds used in American mythmaking. Urban black culture has been represented as hip and freewheeling, while the white middle-class males thought to inhabit the center of professional-managerial life have been showcased as staid and reserved.

Because they’d developed a deeply ironic counterculture that stood up to racial discrimination, urban black men were understood by whites to be among the most successful at insulating themselves from American ideology’s pressures toward conformity and instrumentality. As such, this cohort of black men became, for a white male audience, a perfect populist world for rebellious masculine myths. In recent decades, the nation’s upper-middle-class elite has included African American men who are every bit as committed to American ideology as their white counterparts. Yet black men have remained—in the nation’s cultural imagination—more able to escape the daily grind to create their own culture and pleasures.

“Whassup?!” presented five African American guys whose work lives were out of focus. They seemed to be neither blue-collar nor white-collar. Only Dookie apparently had some vague attachment to a desk job. Rather, because of their vernacular, the audience presumed that these guys grew up in an urban black neighborhood and were still ensconced in hip-hop culture, even though they were self-sustaining adults.

For their fraternity, the friends depended on personalized appropriations of black vernacular: Whassup, B., and true were all colloquial African American expressions. The idiom whassup had circulated in black urban culture since at least the 1920s. More recently, the comedian Martin Lawrence regularly tossed out whassups well before the Bud campaign broke. Like phat, in-the-house, and word, before, young white men had appropriated these expressions to pilfer some of the rebellious attitude associated with black men. The “Whassup?!” ad gave white guys privileged access into the everyday lives of hip black guys and how they interacted.

For younger men who’d grown up in a generation in which much popular culture was dominated by urban African American genres, looking to black guys as mythic figures was commonplace. But for Bud drinkers over the age of forty or so, and particularly men who lived away from big cities, the ads were tremendously polarizing. Older white Bud drinkers didn’t like the “Whassup” spots initially and flooded Anheuser-Busch customer centers with complaints. While many marketers would have pulled the ads, Anheuser-Busch senior managers stuck to their guns. They decided to air the spots with low media weights to see how the campaign would build. After several months, the resonance with the younger audience was so strong that the elders caved in to the emerging consensus. When the company went back to research the elder white drinkers, their opinions had flip-flopped. The Whassup guys turned out to be desirable after all.

This antagonism demonstrates a crucial property of the myths spun by iconic brands. These myths lead culture rather than mimic it, so they necessarily take a provocative stand against conventional ideas. If the advertising doesn’t alienate people who are resolutely tied to a competing ideology, the political vibrations running through the ads are probably not sufficiently compelling to build an icon. Just as Elvis Presley and Marlon Brando disturbed people who wanted to hold on to cultural orthodoxy, so too did Bud’s Whassup guys in their own way.

Utilizing the style and sensibilities of urban black men is an old trick for identity brands, one that often backfires (witness Bud’s “Auction” ad described above). It’s initially puzzling that Bud was able to get away with it. Bud was still strongly identified with the Midwestern heritage of the Busch family and its St. Louis headquarters. The brand’s advertising had always comprised a middle-American vibe, despite its regular nods to racial and ethnic diversity. So why did Bud’s audience quickly accept that Bud was a committed player in urban African American life?

Further complicating Bud’s problems on the authenticity front was the origin of the “True” spot. Before it was turned into an ad, “True” was a popular, independent short film. Anheuser-Busch bought the rights to the film from its writer and director, Charles Stone III. It would not have been surprising if the campaign had been castigated as yet another example of cultural appropriation, in which authentic expressions from black folk culture had been crassly lifted for commercial aims. Once the campaign became popular and the subject of media coverage, the origin of the spots became common knowledge outside advertising circles. Why, then, wasn’t Bud taken to task?

Casting Stone and his friends rather than professional actors was the crucial strategic move that granted the campaign the requisite authenticity. Bud established the credibility to represent the world of “True” because the audience quickly learned that the actors in the ad were real friends, not part of the ad world, and that the film had been “discovered.”

The Anheuser-Busch public relations machine leaped on the public’s interest and launched a campaign within the campaign. The inside story—the making of “Whassup?! ”—was repeated in USA Today, and the crew appeared on Entertainment Tonight, The Tonight Show, and The Late Show with David Letterman. Anheuser-Busch pushed the back story one step further, sending the Whassup guys on a nationwide tour of local talk shows and media events. This story became just as important as the ads themselves. The public relations campaign helped suggest that Anheuser-Busch was not using Madison Avenue chicanery to trick us into falling for some fun-loving black guys. These guys were real friends, they were charismatic in real life, and they’d chosen, of their own volition, to join forces with Bud.

Charismatic Aesthetic: Ensemble Acting in a Low-Tech Production

The verisimilitude of “Whassup?!” relied entirely on the cast’s performances, on the actors’ ability to convince viewers that theirs was indeed a brotherhood of truly hip and fun-loving guys. Persuasive ensemble acting made “Whassup?!” tick. These guys acted as if they’d known each other forever (later on, viewers found out they had). They were entirely comfortable communicating with the most minimal of body language. They mixed in idiomatic phrasings without effort or pretense. They seemed to be actually hanging out rather than reading lines.

In addition, “Whassup?!” incorporated the most minimal production values, precisely the opposite of Bud’s previous advertising. Rather than spectacular shots, editing, and music that suggested a $100 million Hollywood blockbuster, the spots relied on a single, static shot in the apartment, with the characters presented in a flat, democratic manner. The ads were low-budget, one-camera documentaries, not Spielberg. This style established the Bud persona as an intimate, down-to-earth peer rather than a voice from on high.

Managing Cultural and Political Authority

With “This Bud’s for You,” Budweiser delivered one of the most powerful brand myths of the 1980s. When a massive cultural disruption caused the value of this artisanal myth to plummet in the early 1990s, the brand team tenaciously worked to revive the brand, wielding a variety of conventional brand strategies, from mind share to coolhunt to buzz. Despite years of experimentation supported by an enormous media budget, these efforts failed.

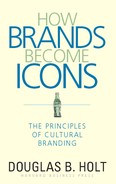

Budweiser finally recovered when the “Lizards” and “Whassup?!” campaigns combined to deliver a new myth. The campaigns targeted an acute contemporary contradiction faced by this constituency: that these men were now unable to forge a heroic brotherhood in their work. Both campaigns drew from an appropriate populist world—racial and ethnic subcultures of American men—to create a myth about the brotherly solidarity that comes from lifelong friendships (figure 5-1).

Budweiser Leverages Cultural and Political Authority to Reinvent Its Myth

This genealogy begs a crucial question left unanswered in the previous chapters: Why are iconic brands able to reestablish such strong loyalty after cultural disruptions? And how is it that iconic brands can pull this off even when they’ve deviated badly from their myths for years? Iconic brands flagrantly violate how brand equity is supposed to work according to the mind-share model, which claims that brand’s equity comes from the distinctiveness and strength of the brand essence and that equity is built by hammering home these associations consistently over time. Both “Lizards” and “Whassup?!” are antithetical to “This Bud’s for You” and also seemingly unrelated to each other. To understand how this about-face worked, we need a new concept of brand equity, one appropriate for iconic brands. When disruptions occur, iconic brands don’t go back to square one. While the brand’s myth loses value, what remains intact is the collective memory of the brand’s prior stories and what these stories accomplished for the people who used them. More formally, when identity brands are successful, they accrue two kinds of assets: cultural authority and political authority. These assets do not automatically convert to brand equity. Rather, managers must reinterpret the assets to align with important social changes to optimize the brand’s equity.

Cultural Authority

Brands that author a successful myth earn the right to come back later with new myths that touch on the same cultural concerns. With “This Bud’s for You,” Budweiser took command of American stories about how men find respect and camaraderie. Consumers came to recognize Bud as an authority for this type of myth, regardless of the specific contents. Americans looked to Bud to tell new stories about how guys create fraternity and find respect. This is the brand’s cultural authority: a brand asset based on the nation’s collective expectations that the brand can and should author a particular kind of story.

Political Authority

In addition to cultural authority, the genealogy reveals the centrality of political authority in Bud’s rebound. Budweiser’s transformation—from the “This Bud’s for You” era of blue-collar cheerleading to the cynical reflexivity of “Lizards” and the overt slacking of “Whassup?!”—is one of the most remarkable reinventions of a brand in recent business history. This repositioning is incomprehensible if interpreted using the conventional mind-share handbook. The protagonists of “Lizards” and “Whassup?!” were the antitheses of the heroic workers of “This Bud’s for You.” The Whassup guys seemed like losers, slackers who mostly hung out, drank beer, and watched television. Their ambitions apparently extend no farther than getting off the couch to get another round. Viewed through the lens of mind share, it looked as if Budweiser not only abandoned its hard-earned equity, but actually subverted its former self.

The transition worked because Budweiser has previously championed a world in which working men can be respected members of American society and gather in solidarity around this status. Consequently, American society looked to Budweiser to create a new myth supporting the identities of these same constituents when the prior myth became obsolete. The problem was that for Bud to successfully deliver on this mission, the politics of its myth had to radically change when nonprofessional men’s conception of work shifted beginning in the early 1990s.

Rethinking Relevance

Building the equity of an identity brand is no easy task. In fact, even maintaining the equity of identity brands that have achieved iconic status has proven to be a considerable challenge, as the fates of Levi’s, Pepsi, and Cadillac each attest.

Conventional branding models lack a coherent approach for managing brand equity in the face of cultural change. Advocates of mind share simply ignore the task and pass it off to their ad agencies, telling them to make the brand relevant while the brand managers control the DNA rudder, charting a path that ignores historical shifts. Viral branding takes just the opposite view: Managers virtually ignore the brand’s past to gravitate to the next big thing. Culture, in this view, is reduced to trends: What’s the latest music, fashion, or catchphrase? In both models, keeping the brand in tune with cultural change is reduced to the idea of relevance, which is understood to mean that the brand communications should fold in materials that have some currency in the popular culture of the moment.

This view of relevance is far too literal, however. It assumes that a brand’s stories work as a mirror, that people simply want to see culture that they like reflected in the brand’s communications. As long as the brand keeps up with fashion, pop culture, and catchphrases, consumers will find it relevant. But identity brands perform myths, not mirrors. They tell stories that are often far removed from anything currently in play in popular culture: an aging crooner taking a dive off a Las Vegas casino (Mountain Dew), a shabbily dressed guy throwing rocks at a tree (Volkswagen), two lizards commiserating in a swamp (Bud). Myths are relevant because, through simple metaphors, the stories address profound social tensions. It is the tension that is relevant, not how the characters are outfitted. Relevance is primarily about identity politics, not fashions or trends.

Iconic brands remain relevant when they adapt their myths to address the shifting contradictions that their constituents face. In the period stretching from World War II until Vietnam, Budweiser had allowed men who otherwise lacked the financial and cultural capacity to have a taste of the idealized suburban lifestyle that enchanted the United States. As this myth became politically untenable, Bud dramatically shifted its communications, championing not consumption but work. Men built intimacy and respect among each other through the heroic qualities of their artisan labor. And when this idea too lost credibility, Bud’s myth was radically reinvented again to champion not a fancy lifestyle or heroic work, but the quotidian pleasures of hanging out with good friends.

Neither “Lizards” nor “Whassup?!” was based on anything trendy. In the case of “Lizards,” one could argue that the campaign was the antithesis of conventional ideas of relevance—it didn’t explicitly reference anything current in popular culture. The Whassup guys, though African American, bore little relation to the sizzling hot world of hip-hop culture found on MTV. Yet these campaigns proved to be extraordinarily relevant to Bud’s constituency. Why? Because both campaigns touched a political nerve. Each addressed intense desires for a new mode of masculine brotherhood that was generated by the country’s massive economic restructuring. For iconic brands, relevance is not about clothes or haircuts. It’s about keeping up with changes in society. As their patrons’ dreams and anxieties get pushed around by real changes in the economy and society, new kinds of myths are needed. Increasing brand equity is all about taking advantage of the brand’s accrued cultural and political authority to create these new myths.

When the brand team understood Budweiser’s equity as brand essence—timeless associations such as American, macho, and classic—they unknowingly abandoned Budweiser’s most valued role for its constituents. These associations locked the brand team into an attenuated set of creative concepts that shirked the brand’s responsibilities to its constituents.

Budweiser succeeded when its advertising finally delivered on its historic political commitments. This return to grace was the result of a daring political flip-flop. In order to side with working men, who were increasingly unable to use their work as a locus of self-respect, Bud advanced a new place for masculine camaraderie: a sanctuary rather than a competitive battlefield, a communal place rather than a heroic project. In “Whassup?!” the easy camaraderie that these guys formed became admirable because, like Frankie in the “Lizards” campaign, they had the self-confidence and force of will to remove themselves from the heat of insurmountable labor market competition. America responded in turn, treating the Whassup guys as heroes and celebrities. These campaigns violated the central pillars of conventional branding. But the brand had returned to the fold politically, reasserted its leadership role among the working men it had deserted in the early 1990s.7

Mountain Dew’s Cultural and Political Authority

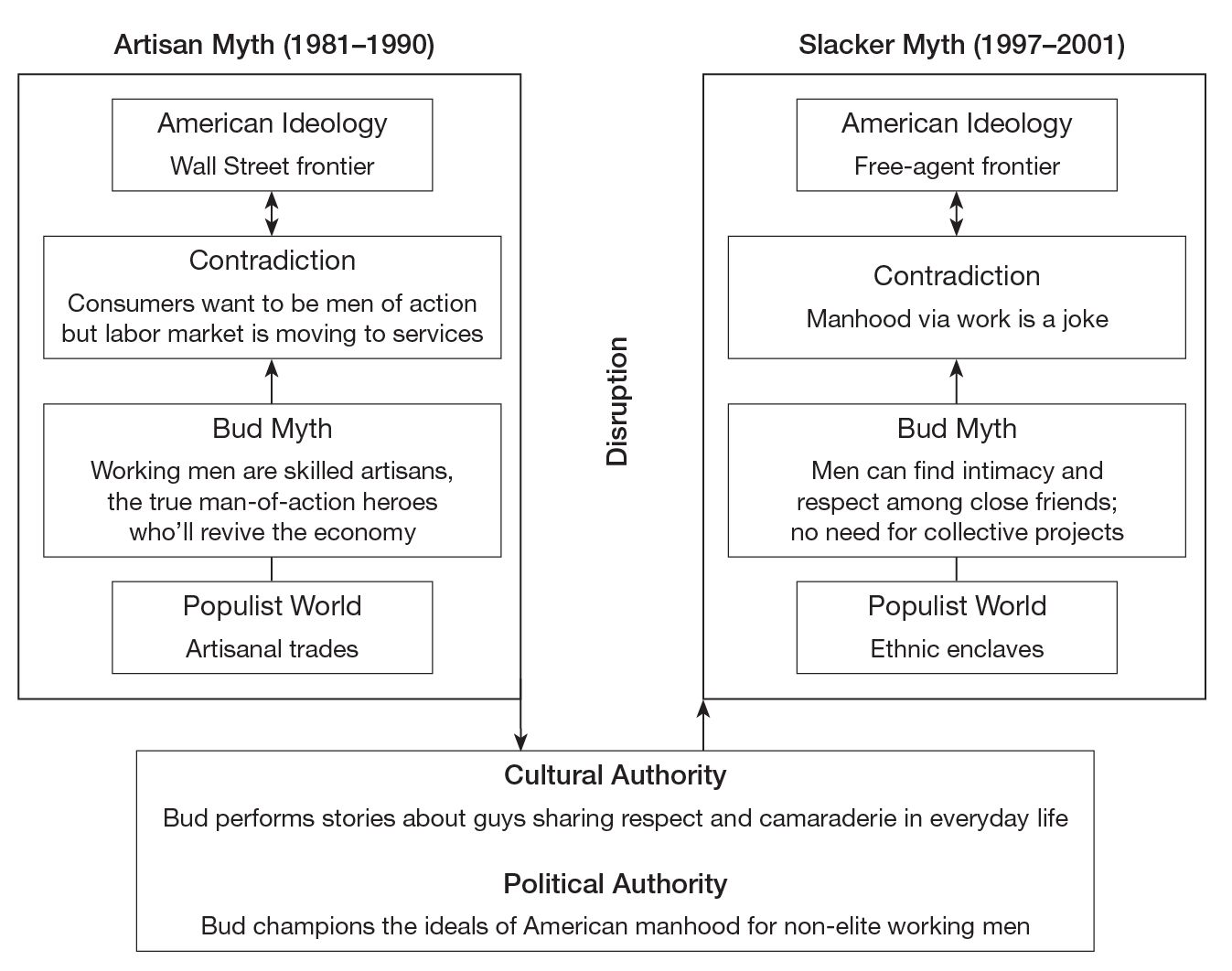

Brand equity also took the form of cultural and political authority for Mountain Dew. In its first two myth markets, Mountain Dew performed identity myths that borrowed from related rural backwoods figures (the hillbilly and the redneck) to celebrate the virility of guys weaned on America’s traditional ideals of frontier masculinity. In the third myth market, Mountain Dew made a break from this rural heritage to create a slacker myth. Why did soda consumers immediately accept these new “Do the Dew” stories?

With its hillbilly and redneck myths, Mountain Dew established its cultural authority to author myths about men’s daredevil escapades in the outdoors. Likewise, these previous myths earned Mountain Dew the political authority to champion for men with less-than-glamorous jobs the ideal that manhood is about virility, creativity, and daring-do rather than about how successful you are at work.

In terms of content, the “Do the Dew” campaign appeared to be worlds apart from these preceding hillbilly cartoons and rural watering hole spots. Yet the brand’s missive was welcomed with open arms because it tapped this deep reservoir of cultural and political authority. Mountain Dew was, again, championing the id over careers for young men who felt excluded from the nation’s definition of manhood. Iconic brands own an imaginative cultural and political space that can be reclaimed virtually at will even if the brand has fumbled or abandoned this commitment for years (figure 5-2).

Mountain Dew Leverages Cultural and Political Authority to Reinvent Its Myth

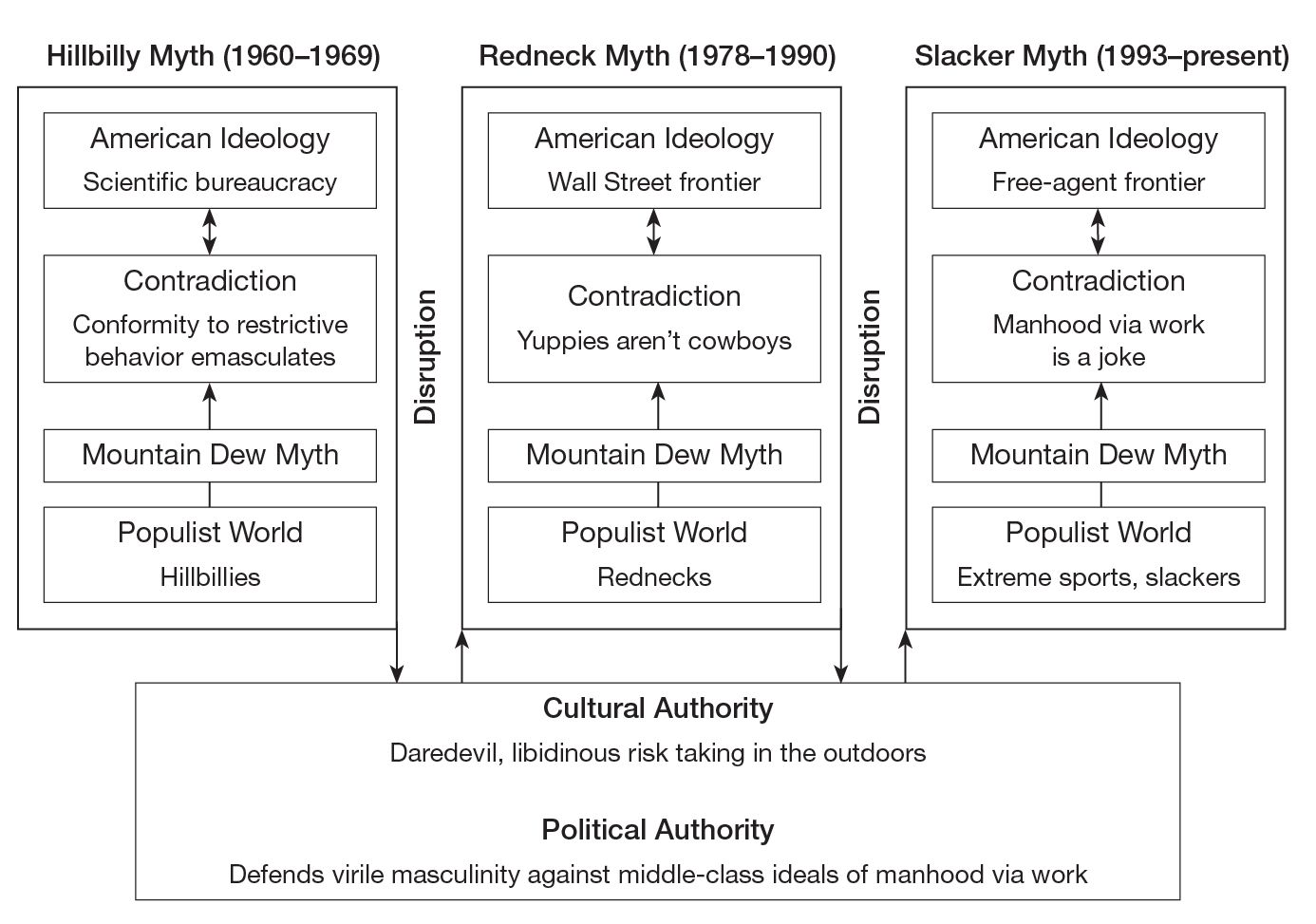

Volkswagen’s Cultural and Political Authority