CHAPTER 7

Coauthoring the Myth

THE HARLEY-DAVIDSON COMPANY (HDC) is nearly everyone’s favorite corporate turnaround story.1 It goes something like this: HDC, which once competed with several dozen domestic motorcycle companies, became the sole American motorcycle manufacturer in 1953 when Indian, its only serious competitor, folded. HDC struggled in the 1960s as new Japanese competitors like Honda and Kawasaki entered the market and quickly dominated the smaller bike sizes. In an ill-fated attempt to expand into other motorized products, HDC failed to extend its business to snowmobiles and golf carts.

As the motorcycle market took off in the late 1960s, the recreational products company American Machine & Foundry Co. (AMF) bought HDC. The quality of Harley motorcycles deteriorated as a result of overly aggressive expansion plans and lackluster, arms-length management. Meanwhile, Japanese bikes made successful inroads into HDC’s core business, big bikes. By the early 1980s, HDC was on the verge of bankruptcy. Senior managers, including the founder’s grandson, Willie Davidson, led a leveraged buyout and took over the company. The new owner-managers turned the company around.

The turnaround was centered on two changes: restoring product quality and getting close to the customer. HDC finally fixed its notoriously leaky engines. But the crux of the comeback was that, instead of snubbing the customers, executives rode bikes with them and fed this learning back into relationship-building efforts, particularly centered on organizing activities through H.O.G. (Harley Owners Group), Harley’s brand community.

Managers love this story and repeat it to each other as a mantra because it celebrates marketing’s “truth.” Harley suffered under the guidance of a conglomerate that ignored the product and the customers. Managers who believed in marketing came to the rescue. They listened carefully to customer wants and, lo and behold, consumer praise and corporate profits followed.

HDC managers approve of this story, also. They also like to say that the brand’s value can’t be analyzed, because it’s magical: There is a Harley mystique that simply can’t be explained rationally. Harley is a quintessential American product that embodies what the nation stands for in an especially pure and profound way.2

Why repeat this story one more time? Harley’s transformation has become one of the world’s most influential branding stories. Managers have spent the 1990s trying to replicate Harley’s path to success. But the Harley story—the official explanation that circulates in the management community as part of business folklore—is wrong.3 So managers and management writers have been drawing the wrong lessons from Harley.

I will demonstrate that the vaunted Harley mystique is nothing other than the brand’s identity myth, embodied in the bikes, which works according to the same principles guiding other iconic brands. In the cases discussed in previous chapters, the company did most of the myth-building legwork. In Harley’s case, however, the company did none of the important storytelling.4 Other authors—the populist world of the outlaw bikers and the culture industries—turned Harley into an icon. Cultural texts—films, newspaper and magazine articles, political speeches, newsworthy events—produced by the culture industries were the key to building Harley’s myth.

Contrary to the advice proffered by countless consultants and gurus, directly imitating Harley is a pointless exercise. Rather, Harley offers an exemplary case to learn about the role of the occasional coauthors of iconic brands—the culture industries and populist worlds.

Harley-Davidson Genealogy

Why did American men who had scorned Harley bikers for decades suddenly, in the early 1990s, desire so intensely to ride a Harley that they willingly sat on waiting lists for a year just to make a $20,000 purchase? And then outfit themselves and their bike with another $5,000 worth of accessories? Harley-Davidson stock began to dramatically outpace the market indices as revenues and profits shot through the roof. The company’s astounding performance was driven largely because the company had increased its prices to levels previously unimaginable in the category.

Harley’s identity value comes from its myth. This myth has moved through three distinct stages. The source material for the brand’s myth—the populist world of the outlaw biker—was created by motorcycle clubs that formed on the West Coast after World War II. The culture industries produced an initial wave of cultural texts, from the early 1950s until the mid 1960s that glamorized the biker’s outlaw ethos and stitched their story to the Harley bikes. From the late 1960s to the late 1970s, influential cultural texts repackaged the myth, transforming the outlaw into a reactionary gunfighter. As a result, Harley became iconic for lower-class, white, male customers, as this gunfighter myth addressed their identity anxieties. Beginning in the late 1970s, a third wave of very different cultural texts once again revised Harley’s myth—heroizing the rough-and-tumble gunfighters as men-of-action who can single-handedly save the country. This man-of-action gunfighter myth took off in the early 1990s, but this time connecting with the older and wealthier middle-class male customers who have made Harley such a venerable economic asset today. The culture industry’s impact in stitching the myth to Harley and then repackaging the myth led to Harley’s extraordinary financial success in the 1990s.

Motorcycle Clubs Invent the Outlaw Ethos

After World War II, veterans joined with lower-class city kids, primarily in California and other warm-climate states, to form a countercultural scene centered on biking. These motorcycle clubs were a tightly bound community of men who created an alternative social world. Harley was just one brand of large bikes—Indian and Triumph were others—favored by these motorcycle enthusiasts. Any bike that was big and loud would do.

Modifications to the bike were much more important than the brand. To convert these motorcycles from their gentlemanly touring dispositions into bikes fit for outlaws, bikers removed “ornamental” features such as fenders and trim, installed smaller gas tanks, and modified engines to increase performance and provide a sleeker look. These customizations eventually led to new frame designs, the most famous of which became the extended front fork, the “chopper.” In local shops across the United States, an informal economy developed for customizing large bikes.

Ethos of the “Outlaw” Motorcycle Clubs

The following principles constitute the ethos of the outlaw motorcycle clubs, as distilled from ethnographic studies of these groups.5

Libertarian life: Outlaws are nomads, always on the move. They’re not tied down by jobs or restrictive relationships. A primary expression of freedom for these bikers is the ability to take off and go anywhere at any time. While rallies draw attention, the ideal is to ride without a destination. More than merely supporting libertarian views, outlaw bikers seek a life in which institutions of any kind—the state, the courts, the media, corporations, marriage—are held at bay. All institutions are emasculating because they steal the ability to act autonomously.

Bikers speak condescendingly of middle-class men, those successful in business and respected in society, as “citizens”—conformists who adhere too closely to society’s rules. Outlaw bikers invert the typically positive connotations of the term citizen to reveal its dark side: the loss of individuality that accompanies participating in society, the need to conform to institutional norms, the lack of soul. The citizen’s world of masculinity is hypocritical. It pays tribute to freedom and individuality, but adheres to strict conventions and willingly accepts limits on individual freedom.

Physical domination: Manhood is about domination, that is, toughness, aggression, and the ability to confront danger with confidence. Bikers ritualize fighting. Club brothers often fight violently with other clubs’ members. Outlaws brandish an intimidating, interpersonal style. They enjoy placing a little terror in the minds of other men in their presence. Outlaws ride “hogs”: big, loud, aggressive, basic primal machines. Outlaws further modify Harleys to accentuate the bike’s expression of domination. They remove the muffler to make the bike louder and faster.

Tribal territories: Outlaw bikers see life as a territorial battle, fought against peoples of other nations and races, in which manhood comes with successfully defending the territory one shares with other like-minded men.

Danger: On the frontier, manhood was earned through surviving dangerous risky encounters with Native Americans and nature. Outlaws ride motorcycles. Every time he rides a motorcycle, the outlaw biker depends on his skill and bravery to stay alive, a fundamental aspect of being a man. Outlaws refuse to wear helmets, or they wear helmets that provide little protection. Bikers think that citizens do whatever they can to rid their life of risks. To outlaws, cars are cages, biker slang for an auto, with as many safety features as possible to protect the passengers from harm.

The wild life: Outlaw bikers pursue a life of pleasures, avoiding civilization’s constraints. Bikers are happy to trade off the security of a settled lifestyle for the pursuit of the wild life—a life governed by thrill-seeking, intense pleasures, and the unknown. Citizens’ actions are governed by instrumental goals, how one has to behave to be successful. Citizens are always planning for the future and living for the job, the family, and taxes. A biker carouses with his brothers; looks for excuses to get high, find a little bit of trouble, and exercise his hog on sun-bleached country roads. If a biker inadequately demonstrates his commitment to the wild life by succumbing to job or family pressures, his brothers harass and scold him. If the wayward brother continues to behave too much like a citizen, he is excommunicated from the club.

Nature: Outlaw bikers think of themselves as living in the grip of nature, and their lifestyle makes this point over and over. They live with nature, which is signified by dirt and odors. Outlaws wear dirty clothes, have beards and long dirty hair, and bathe infrequently. And while citizens travel in heated, air-conditioned automobiles, outlaws express their organic nature by riding motorcycles, fully exposed to rain, cold, and the sun’s searing heat.

Misogyny: Outlaws create a patriarchal world, demanding that their women be docile, obedient, and subservient to their sexual needs. Bikers ritualize their dominance over women in many ways. Women are not allowed to join the clubs and cannot be in the clubhouse without escorts. Women are allowed to participate in the club only if they assume the appropriate role. Domination is at its extreme in sexual relations, in which women are expected to serve the members’ sexual demands, whatever they may be. Sharing partners is commonplace. A clear sign of the dominance over women is the woman as passenger on the back of a hog. In the bikers’ world, women never drive. Women are dangerous because they represent the settled world of families and commitments; they have the power to “lure” men away from their commitment to the club’s ethos and back into the world of the citizen.

Know-how: Frontiersmen weren’t able to rely on the specialized skills of other men, as one would do in modern society. They had to know how to make do, how to repair everything they owned, and how to improvise to get by. Outlaw bikers take perverse pride in the frequent breakdowns of older Harleys. Since outlaw bikers view a man’s mechanical competence as evidence of his masculinity, a sick hog is nothing more than an opportunity to demonstrate that one has the know-how to live in a world free of dependency. Outlaw bikers build their bikes to suit their tastes. Citizens live in a world in which men need technology and the specialized expertise of others. Because they have no idea how their autos and bikes work, they must rely on others; their vehicles are an umbilical cord to dependency rather than an escape to freedom.

Men in motorcycle clubs were inspired by the outlaws of the American West, like Jessie James, and viewed their bikes as their mechanized horses. In their clubs, they invented a modern outlaw life. On the Western frontier, men were bound by few laws. Every man had to learn how to fend for himself in a Hobbesian world wherein the toughest man—often the most violent man—prevailed. While many nineteenth-century pioneers may have viewed the West as the land of opportunity, a place to achieve the American Dream, outlaws found in the West a place to escape modern society. Post–World War II bikers’ imagined their own version of the outlaw ethos, which has remained more or less consistent ever since.

From the 1950s onward, these motorcycle clubs lived and honored the outlaw life, keeping alive these ideals at a time when American ideology lauded exactly their opposite: scientific expertise, rational administration, and the planned nuclear-suburban life. These motorcycle clubs soon became a potent populist world, standing alongside the cowboy, the hillbilly, the urban African American, and the beatnik as the most resonant populist figures able to challenge America’s dominant postwar ideals. As the bikers were transformed from their isolated existence on the West Coast to nationwide media darlings, a significant biker myth market emerged for which Harleys eventually became the central prop.

This ethos would have remained stuck within the circle of motorcycle clubs and their hangers-on had it not been for the culture industries, which quickly realized that the bikers made a great story. When these industries propagated the outlaw biker story, they converted the biker into a mythic figure for their mass audience, and attached this myth to the Harley brand.

Stage 1: Cultural Texts Stitch the Outlaw Myth to Harley

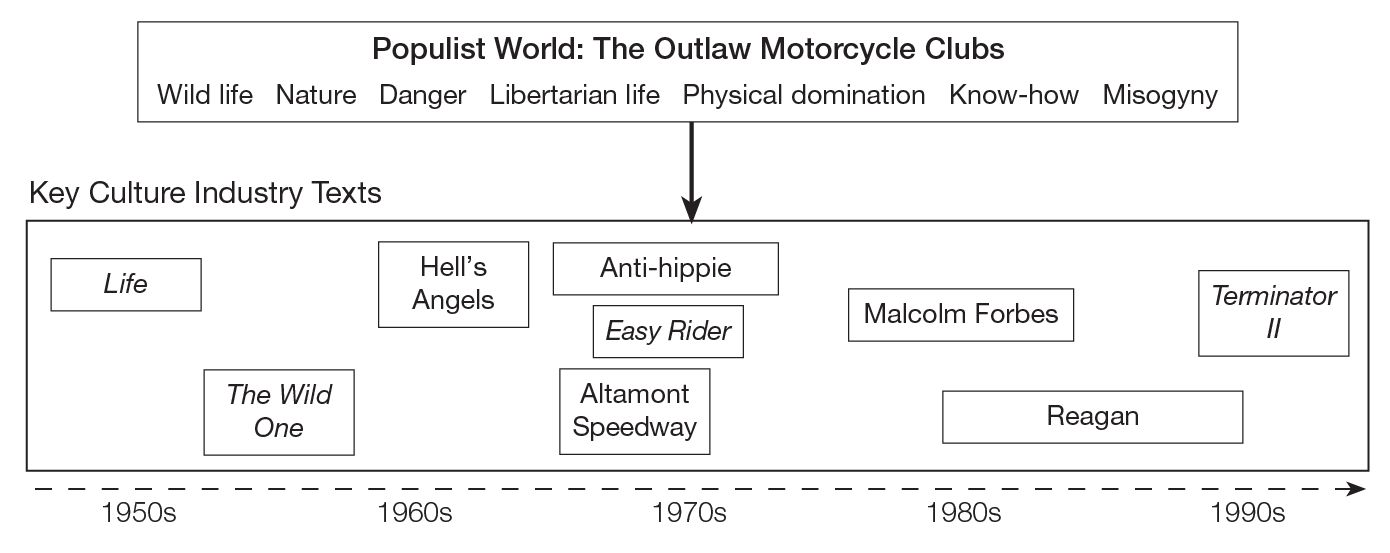

Three key cultural texts harvested the outlaw biker clubs as source material: a Life magazine exposé, the film The Wild One, and the various journalist reports and film renderings of the escapades of the Hell’s Angels, (figure 7-1). In their function, these three cultural texts operated no differently than the thirty-second ads described in prior chapters. The texts coauthored an identity myth, located in the populist world of the bikers. The key difference is that, at the beginning, the stories focused on the bikers rather than their brand of bike. So, initially, the iconic figure was the actor in the story (Marlon Brando, the Hell’s Angels). But, as Harleys became an increasingly central figure in these stories, the biker myth gradually transferred to the Harley as well.

Time Line of Key Culture Industry Texts

Life Magazine

As the Cold War paranoia of McCarthyism frightened the nation into nervously enforcing nuclear family norms, the motorcycle clubs proved to be perfect fodder. Over a Fourth of July weekend in 1947, a motorcycle club drank, caroused, and toyed with the locals on the streets of Hollister, California. Life magazine ran a “morning after” photo of a drunken man, his eyes glazed, his bulging stomach popping out of his shirt, swilling a beer while leaning back on a Harley. Dozens of empty bottles lay underneath the cycle. Life ran the photo to dramatize the magazine’s description of a biker riot disrupting a small, defenseless town. The image sent a shock wave through respectable America. Suddenly, parents had to worry about debauched sexual predators on the loose—bikers—who obeyed no law and whose only objective was to cause trouble to decent, law-abiding citizens.

Though the photo was staged by the photojournalist, its cultural effects were pronounced.6 The bikers provided a threatening counterpoint that gave meaning and motivation to the nation’s ideological agenda. Bikers were hooligans on the loose, men who refused society’s discipline and who had to be suppressed. To protect itself, American society had to rally against these barbarians.

The Wild One

While the Life incident created bikers as threatening hooligans, it was The Wild One, Hollywood’s take on the Hollister spectacle, that provided the philosophical underpinnings of their way of life, giving purpose to their fighting and drinking and antisocial behavior. In the movie, Marlon Brando starred as the leader of a hooligan biker club looking for trouble. His gang passed through a small Norman Rockwell–esque town. For Brando, everything in the town reeked of square—a term, borrowed from the Beats, meaning dull conformity—a direct jab at the American ideology. Brando’s merry band of bikers turned the town into a raucous party, overrunning the bar, harassing the women, and instigating fights. Lee Marvin, playing the macho leader of a rival gang, rode into town with his gang, got drunk, and picked a fight with Brando. They bloodied each other and tensions rose as the party surged out of control. Later, Brando took a waitress from the bar on his bike for a supposedly romantic interlude in the countryside. Aloof and worried that he lacked the proper civilities to impress, however, Brando rejected her before she could do likewise. Near the film’s end, the town fathers, mobilized into a vigilante squad, trapping Brando and badly mauling him. As he fled on his cycle, one townsman heaved a tire iron into his wheel spokes, which threw Brando from his bike.7 As the cycle spun out of control, it collided with an innocent man, killing him. Brando eventually beat the ensuing homicide charge. Along the way, though, the waitress fell in love with him. But Brando’s troops were calling. So, as a true biker, he passed on the girl and rode into the countryside with his biker brothers.

The Wild One portrayed motorcycle clubs much as the members imagined themselves—as frontier outlaws. Like other men, bikers felt emasculated by the new technocratic U.S. ideology, but they possessed the courage to reject society and live out man’s animal nature, much as did men in the Wild West, where no regulating bureaucracies governed men’s actions. These men relied on physical dominance and staying on the move to avoid coercive commitments. Providing a mythic resolution to the nation’s anxieties with the regimen of organization men and suburbia, Brando and Marvin were received as sexy rebel heroes. Along with James Dean, Brando became an icon of youth rebellion. He allowed men to dream of escaping the feminizing conformity of society using simple tools: black leather, denim, and a loud motorcycle.

Media Portrayals of the Hell’s Angels

In 1964, bikers from a little-known motorcycle club were accused of raping a girl in a small town. The story broke in all news outlets, reviving the idea that bikers were barbarians. This time, however, the outlaw bikers had a name to match their dangerous reputation—the Hell’s Angels.

Until the rape story broke, the Hell’s Angels were a small gang of a few dozen men in northern California. Although they had attracted police attention for years, they had hardly struck fear into law enforcement. Soon after the incident, though, the bikers became media darlings, providing a voyeur’s delight of sex, violence, crime, and filth all rolled into a single photogenic package. Again the nation was on the lookout for these thuggish barbarians, sexual predators who hunted society’s daughters. The media frenzy transformed Hell’s Angels into an explosive cultural force.

The B-movie impresario Roger Corman knew incendiary plot material when he saw it. Corman oversaw production on several biker films, including the box office smash Wild Angels. He encouraged his screenwriters to embellish the bikers’ deviance to exploit nearly every perversion and aberration: “devil worship, sadomasochism, necrophilia, monsters, space aliens, Nazis, the Mafia, and every aspect of the occult, even bikers as transvestites.” 8 Psychopathic cult leader and murderer Charles Manson, one the era’s most disturbing cultural figures, apparently was inspired by Corman’s films. Manson announced that he would lead his revolutionary charge riding on Harleys.

For boys growing up in the 1960s, the repulsive and ominous Harley riders exuded an irresistible attraction. The Harley was to a teen coming of age in 1965 what a punk’s safety pin through the cheek was for a lad in England circa 1979 and what falling-off-the-butt, baggy jeans were to boys entranced by “gangsta” culture, beginning in the late 1980s. All these images were extraordinarily enticing to youths because they threatened bourgeois adults. The problem for Harley was that while a teenager had no trouble scoring a safety pin from mother’s sewing kit, a $3,000 bike was another matter. Instead, Levi’s and black leather jackets became choice gear for teen biker wannabes.

Hunter S. Thompson, the hip and influential gonzo journalist of the counterculture, trumpeted the inside story of the Hell’s Angels in widely read exposés in Rolling Stone and The Nation and then in a documentary-style book in which he described his escapades as an Angels hanger-on. While the Angels that Thompson described were too violent and too misogynist for hippie tastes, they nevertheless commanded great respect because the bikers were “the real deal.” These guys, more than any hippie, were rejecting everything to do with American society. They possessed authenticity in spades. They said “fuck you” to everything.

Stage 2: Repackaging the Outlaw as a Reactionary Gunfighter

In the late 1960s, two important cultural texts shifted Americans’ understanding of the bikers from lawless and amoral outlaws to still dangerous but now nationalist gunfighters. Historically, American gunfighters were mercenary outsiders—Daniel Boone was the first popular version—who faced down savages (Native Americans) with the professional skills of a warrior. Gunfighters were uncivilized, but necessarily so because it gave them the toughness to take on the enemy.9

The roots of Harley’s gunfighter myth were established during World War II, when various newsreels, newspaper photos, and stories depicted soldiers riding Harleys on the front much like a cavalry of old. Harley had become the new horse of the U.S. military. Soldiers cherished Harleys, along with Jeeps and Zippo lighters, as a trusty tool of battle. But this idea that men astride motorcycles were soldiers doing battle for the country was pushed aside by the domination of the outlaw myth.10 Two key cultural texts—Altamont and Easy Rider—revived the idea that Harleys were the trusty steeds of the gunfighter.

Altamont

In December 1969, the Rolling Stones, on their Let It Bleed tour, performed at northern California’s Altamont Speedway. Inexplicably, the Hell’s Angels were hired to protect the Stones from the huge crowd. They pulled their choppers between the stage and 300,000 Stones fans, who were impatient from a several-hour delay past the concert’s advertised start time. The crowd became aggressive as the Stones finally took the stage and pressed against the Angels’ bikes. Fighting broke out. A man pulled a gun on an Angel, and the bikers responded by knifing the guy to death. A media feeding frenzy ensued. The impression given by media coverage was that the Angels were willing to fight the hippies to maintain order and defend their honor.

Altamont was a decisive break between the hippies and the motorcycle clubs. The Angels’ actions against the hippies came at a time when a reactionary appeal for law and order was being made by President Richard Nixon and Vice President Spiro Agnew. And more conservative-minded citizens, particularly the white working class, were also taking up the cry. The Angels’ stabbing was a poignant metaphor for these people’s desire to squelch the political instability spawned by the civil rights and the peace movements. In the conservatives’ minds, the hippies symbolized this instability: the country’s sons and daughters who were led astray by distorted ideas. So those who sided with law and order took away from Altamont a different impression of the Hell’s Angels: bikers may be violent, but they were also patriotic and conservative in a way, because they were more than willing to defend the nation’s historic values.

The impact of Altamont was seconded by widely reported news stories covering the anti-peace-movement antics staged by the increasingly media-savvy Hell’s Angels. The peace movement was beginning to have an impact, and Nixon and Agnew implored the “silent majority”—predominantly white, working-class men who lived in the interior of the United States and who supported the war effort—to voice their support for the war. Although the Angels had little admiration for politicians, including the Nixon administration, they deplored the hippies’ apparent lack of respect for their brethren, the soldiers fighting in Vietnam. The Hell’s Angels staged counterprotests at antiwar rallies, taunting peace protesters and occasionally inciting violence. The Angels’ head honcho, Sonny Barger—no fan of the government—even sent a letter to Nixon volunteering the entire Hell’s Angels membership to enlist as soldiers in Southeast Asia.

The American flag became the sign around which this contest was waged. While protesters burned flags, the bikers proudly waved them and placed flags on their bikes. The Harley-Davidson Company finally followed the bikers’ lead and introduced a new chopper model that mimicked the bikers’ modifications. Moreover, the company changed the Harley logo to incorporate the stars and stripes.

Easy Rider

Peter Fonda’s and Dennis Hopper’s 1969 film, Easy Rider, was one of the defining films of the Vietnam era. Consciously made in the style of a Western, Easy Rider’s impact resulted from its mix-and-match pastiche: Like The Wild One, the film celebrated masculine autonomy, but instead of a biker gang, we get solo motorcycle riders moving through a frontier setting in the American West, burnished with plenty of hippie dress, drugs, and lingo. Like the Westerns of the 1950s and 1960s, Fonda and Hopper used their movie to confront a society they viewed as sickly because it stole men’s autonomy. They cast themselves as hippie drug dealers who financed their escape from society with the proceeds from dealing large quantities of cocaine. With soundtrack accompaniment by the rock band Steppenwolf’s “Born to Be Wild,” Easy Rider’s protagonists rode through the desert transporting the drugs in the gas tank of Fonda’s chopped Harley, which had been painted like an American flag.

In a nod to The Wild One, Fonda and Hopper pull into a small town and ride their bikes in a town parade as a joke. They’re thrown in jail, where they meet an alcoholic ACLU lawyer played by Jack Nicholson. In a role that helped make him a star, Nicholson plays a liminal figure. Dressed in fine white linen, he clearly lives a comfortable life in bourgeois society. But, unable to resist his desire for the uninhibited life, he decides to join Fonda and Hopper on their ride. Explaining why the two were run out of town by the law-and-order town fathers, Nicholson lectures Hopper:

This used to be a hell of a good country. They’re not scared of you. They’re scared of what you represent. What you represent to them is freedom. But talking about it and being it are two different things. It’s real hard to be free when they’re bought and sold in the marketplace.11

Easy Rider redirected young American men, then enamored by hippie ideals, toward the frontier values found in the period’s Western films. The film told young men that the pursuit of freedom was about recovering the individual freedom promised by America’s frontier, not about debating existential philosophy or communal living. Aside from a hallucinogenic visit to New Orleans, most of the film unfolds in the rural West. The men ride bikes and camp out, running into ranchers and hippies along the way.

Fonda, Hopper, and Nicholson push the idea that American manhood rests on a libertarian world of pure autonomy that men once found in the West. Fonda and Hopper eat lunch with a ranch family that is seemingly conservative in its way of life, exact opposites of the hippies. Yet Fonda praises the rancher’s life: “It’s not every man who can live off the land, do your own thing in your own time. You should be proud.” Later, in a stoned soliloquy around the campfire, Nicholson describes a higher-order species from another planet: “Each man is a leader. There is no government. No monetary system.”

Easy Rider portrayed bikers as lay philosophers of the frontier. The country’s large institutions drained men of their masculinity because it forced them to conform to “unnatural” roles and norms. So to recover one’s manhood—one’s freedom—one must reject city life for the rugged and independent life only to be found in the country, riding a Harley, of course. Freedom wasn’t to be had in a Sartre reading group, a folk concert, or hanging out with a barefoot and braless hippie girl. True freedom was something that men pursued on their own, jettisoning dependencies on the government and large companies.

Altamont and Easy Rider worked together to repackage Harley’s prior outlaw myth. Now Harley’s myth showcased that these dangerous and hedonistic men were also stewards of the country’s traditional masculinity and libertarian values. Harley bikers played the role of America’s historic gunfighters: dangerous tough guys who would do whatever it took to restore the country’s historic rugged individualism, a country that would once again celebrate white men’s autonomy and power.

Harley’s myth of the reactionary gunfighter found a waiting audience. Working-class white men who were disturbed by middle-class men’s experiments with a kinder, gentler masculinity proved to be a perfect fit. Many of these men became rabid Harley enthusiasts, a counterculture formed as a reaction to the progressive zeitgeist of the day.

Harley Becomes an Icon

Harley became an icon for working-class white men well beyond the smallish circle of outlaw bikers. These men were facing an emasculation crisis of sorts as production jobs started to disappear and the United States entered a painful era of deindustrialization. Japanese companies began to dominate markets in consumer electronics, transportation, industrial machinery, and steel. At the same time, middle-class Americans began to experiment with a progressive ideology that envisioned a new future premised on ecology, feminism, civil rights, and the existential cultural experiments of the hippies. Alan Alda, not John Wayne, was the new role male model.

For young working-class white men, this was an anxiety-ridden time. Their economic futures were threatened at the same time that the nation was abandoning the patriarchal model of manhood that they believed in. These men were drawn to the story of the Hell’s Angels as holdouts who still revered manhood as practiced in America’s frontier past. They liked the idea that the outlaw bikers stood firm against the middle-class hippies, whom they viewed as overprivileged sissies. The idea of riding a Harley in a motorcycle gang became the last bastion of manhood, defending America’s frontier values against the alien ideals proposed by the middle-class people living on the coasts. These men were easily able to displace wartime aggressions toward the Viet Cong to the new enemy—the “gook junk” Japanese motorcycles that had invaded the American marketplace. Epithets easily blended as the Vietnamese peasant and the Japanese motorcycle were re-imagined as having sprung from the same totalitarian, feminizing, un-American well. Years before Michigan auto workers began ritually smashing Hondas and Datsuns with Louisville Sluggers, Harley bikers proudly wore t-shirts printed with slogans that savagely attacked Japanese motorcycles. As a rallying point for this reactionary movement, riding Harleys became a circle-the-wagons exercise, a way for similarly disaffected men to gather in common cause against the evil forces of liberalism lurking everywhere in contemporary America and against the foreigners who were stealing their jobs.

An informal network of Harley riders grew into an extensive national Harley biker organization—the Modified Motorcycle Association—which sponsored rides and rallies. Easyriders magazine, these bikers’ favorite read, began a political action group called ABATE. Originally, ABATE stood for A Brotherhood Against Totalitarian Enactments, but was eventually changed to the more politically acceptable A Brotherhood Aimed Toward Education. ABATE opposed helmet laws that were then being introduced state by state. These laws operated as a potent symbol for the encroachment of wrongheaded, liberal government ideas into the personal lives of American men.

With its glossy spreads of Harley after-market customization jobs, biker rally candid photos, and bare-breasted “Harley women,” Easyriders celebrated the outlaw biker lifestyle. The publication’s editorial direction gives us a flavor of Harley’s followers at the time. The magazine explicitly promoted an ethos that aligned exactly with the outlaw biker clubs: antiauthoritarian, anti-elite, and against social norms of any kind. It celebrated what mainstream society would consider the most vulgar and offensive ideas and acts. “Fuck the world” (“FTW” appeared on the masthead) was the dominant motif. “In the Wind,” a section of the magazine that published photos sent in by readers, almost always featured subjects giving the finger. Occasionally, a small child was encouraged to pose on a chopper and flip off the photographer. Women, usually with their shirts pulled up to expose their breasts, often gave the bird. Flipping the middle finger did not mean that the subjects could not smile. They often did.

The FTW aesthetic was central not only to the monthly columns, but also to most fiction published in the magazine. Stories often included what might be considered nonconsensual heterosexual sex, and at least one story was told from the viewpoint of the rapist, who was the hero. The rape theme was pervasive in the jokes, pictorials, and readers’ letters as well. In a 1977 photo feature, a naked woman is shooting pool and she’s held down onto the pool table, clearly struggling against a half-dozen bikers, and the rest is up to the readers’ imaginations.

Easyriders was so successful that imitators (e.g., In the Wind, Outlaw Biker, and Runnin’ Free) sprung up. By the late 1970s, combined circulation of the top five publications reached over one million readers. Harley had become an iconic brand for white guys on the lowest socioeconomic rung of American society, serving as a powerful container celebrating the reactionary gunfighter ethos. These men were bound in a fraternity that celebrated a virile, patriarchal, misogynist manhood that they vaguely imagined to have existed in preindustrial America.

As a result, in 1970s United States, Harleys were decidedly unacceptable among middle-class men, a sign of backwardness that pushed against the grain of the progressive zeitgeist of the day. For the Harley-Davidson Company, then owned by AMF, this iconic status was hardly a victory. These working-class customers picked up their tastes directly from the outlaw bikers and loved working on used bikes, modifying them with their own customized designs. Old, pre-AMF bikes were favored as the more authentic species. These preferences aligned well with working-class pocketbooks; many men couldn’t afford a new machine, anyway.

Stage 3: Repackaging Gunfighters as Men of Action

While Harleys were immensely valued among young down-and-out white men who valued the patriarchal ideals that had become imbued in the bikes, they were anything but desirable among the middle-class, middle-aged white men who would become Harley’s acolytes in the 1990s. How could Harley’s thuggish gunfighter myth be revamped in a way that appealed to men with desk jobs earning $100,000 a year? Ronald Reagan and his gunfighter celebrity friends repackaged the Harley myth in the 1980s, preparing the ground for the anti-PC (anti–politically-correct) myth market that blossomed in the early 1990s.

Reagan Promotes Gunfighters as Men of Action

The rise of Reagan as the most influential American cultural icon and his strategic use of Harley was the single most important cause of Harley’s resurgence. As a way to jump-start U.S. economic and political might, Reagan revived Teddy Roosevelt’s turn-of-the-century gunfighter myth. Reagan used his cultural authority as a star in the B Westerns of the 1940s and 1950s to reinvent the myth.12 He spun a populist myth about a reawakening of the American spirit and delivered magnetic sermons on what made America great. He believed that the United States had a destiny divined from God, replaying John Winthrop’s claim that the nation was a land of chosen people, “a city on a hill.” As he pronounced a boyish faith in American goodness, he expressed disdain for government bureaucracy and elite expertise, and most important, he vowed to stand up to U.S. enemies. His capitalist take on the frontiersman painted the entrepreneur and small business as the engines of American success. To make his critique of bureaucracies and elite insiders stick, Reagan transformed America’s historic gunfighter character into a man of action: a heroic figure who could single-handedly take on corrupt institutions in order to salvage the country’s traditional values.

Roosevelt had used the figure of the gunfighter as the symbol of U.S. ambitions as an emerging global power after the Spanish-American War. Reagan called for the revival of Roosevelt’s gunfighter ideals to overturn what he viewed as sickly institutions and a weak national spirit. He used Sylvester Stallone’s Rambo character—a renegade Green Beret from Vietnam—as the quintessential gunfighter figure. And he routinely invoked the most prominent gunfighter actors—John Wayne and Clint Eastwood in particular—as symbols of his ideological revolution. Just as Reagan encouraged Americans to revel in these figures as heroes, he acted as a man-of-action gunfighter himself, taking on Noriega in Panama and Gadhafi in Libya, renewing a hard line with the Soviet Union and Iran, and supporting the contras as freedom fighters against the Sandinistas in Nicaragua.

Reagan’s charismatic call to resurrect a nation of gunfighters galvanized men across the class spectrum. By his reelection in 1984, previous party allegiances had broken down. Instead of the class- and ethnicity-based alliances that had held since Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, Reagan organized a new alignment that was strongly influenced by his ideals of manhood.

On the economic front, Reagan picked up on the working-class backlash, treating the Japanese like the American Indians of the day. The Japanese had “attacked” the United States, so it had no recourse but to fight back. The administration painted the Japanese as public enemy number one, an economic threat to American power and prestige. While the United States seemed able to win the Cold War against the Soviet Union, Japan—with its superior business practices and long-term determination to penetrate export markets—appeared economically unstoppable. In the early 1980s, protests against Japanese capital investments in U.S. real estate such as Manhattan’s Rockefeller Center and in American culture such as film and music companies became common.

On the cultural front, Reagan honed the rhetoric developed by neoconservative intellectuals in the 1970s, excoriating “liberal elites” who’d corrupted the nation by dethroning American heroes and forcing anti-American ideas into the educational curricula and the media. He attacked the social agenda that emerged from the 1960s, calling it antireligious and unpatriotic and claiming it favored socialist ideas over morally superior laissez-faire individualism. Reagan found cultural elites to be wimpy, and mainstream America agreed.

Three key cultural texts repackaged Harley to evoke these man-of-action gunfighter ideals. These texts transformed the brand’s unvarnished reactionary version of the gunfighter. The new gunfighter was still violent and patriarchal, but he was also a heroic man of action who had the power to save the country. This revival of the man of action proved to be exceedingly attractive to conservative middle-class men.

Malcolm Forbes’s Capitalist Tools

While Reagan was building his political base in the late 1970s, one of his key allies, Malcolm Forbes, was already touting Harley’s effectiveness as a symbol of the gunfighter myth. Forbes, publisher of his namesake Forbes magazine and renowned right-wing ideologue, was a publicity-seeking celebrity in his own right. He arranged adventurous trips on Harleys, which were widely reported in the press. He and his “Capitalist Tool” riders would fly their Harleys to exotic and often politically sensitive “frontiers” like Afghanistan, take a ride, and then present the local authority with a gift, a Harley. He also led “freedom rides” for libertarian causes on his Harley. Forbes applied his famous name to the Harley dealership he owned. Behind a limo that broke the Manhattan wind for him, Forbes often cycled to work on one of his Harleys.

Forbes crafted the Harley gunfighter as a distinctly capitalist figure. Harley riders were warriors championing capitalism and liberty in the face of socialist threats. These men had the virility to reinvigorate society with libertarian values. For Forbes, unlike the working-class riders who preceded him, Harleys symbolized a potent type of masculinity within the world of business. Being a man meant pursuing the life of a rugged individualist manager, as an entrepreneur willing to take death-defying risks both professionally and personally. It meant being manly in demeanor and conservative in politics and social mores. In Forbes’s view, real capitalist men were defiant entrepreneurs who thrived in a world of competition.

Reagan Anoints Harley as Man of Action

In the early 1980s, Harley was still suffering from mismanagement (AMF had expanded too rapidly and with poor quality controls), a recession, and the debt taken on by a management-led leveraged buyout. The Reagan administration was well aware of Harley’s precarious financial position and was worried about the political fallout if it allowed a company with the heritage and symbolism of Harley to slide into bankruptcy. In April 1983, Reagan came to Harley’s rescue. He imposed a huge tariff increase against imported heavyweight motorcycles and power-train subassemblies (from 4.4 percent to 49.4 percent) to protect Harley’s business. The political task was to spin the bailout to make an overtly protectionist policy align with the administration’s laissez-faire rhetoric.

Again proving his rhetorical wizardry, Reagan skillfully wove Harley into his efforts to revive the gunfighter myth. He told Americans that because HDC had been wronged by America’s economic foes (the Japanese), the nation must rally around Harley, especially since it was the last American motorcycle company.

Although Reagan had effectively enlisted Harley into his vision of the frontier, alongside the mythical gunfighters friends Stallone, Wayne, and Eastwood, the brand received little benefit from these ideological coattails at first. First of all, the real capitalist gunfighters were to be found predominantly on Wall Street, working as investment bankers and corporate raiders. Harley’s ties to rural working-class guys didn’t make sense in this environment. Second, the story was all wrong. The nation was hungry for strong men who could effectively topple the old model of capitalism and, then, conquer America’s aggressive new rivals. Wall Street bankers fit the mold; the Harley-Davidson Company did not. Harley seemed to be a fumbling old-economy company, beaten up badly by the Japanese, and with a history of attacking rather than backing bikers. Not exactly the heroic frontiersman that American society wanted to rally around. Rambo worked much better.

But as the five-year tariff protection approached expiration in 1987, the Reagan administration schemed with Harley management to pull off an extraordinary public relations coup. On March 19, Harley CEO Vaughn Beals asked the International Trade Commission to cancel its tariff protection—a purely symbolic move as Honda and Kawasaki had moved production to the United States to avoid the tariff. What’s more, the tariff, which started at 45 percent of wholesale prices, was to be only 10 percent in the last year. On May 6, Reagan gave a speech from the factory floor of Harley’s York, Pennsylvania, plant, proclaiming, “American workers don’t need to hide from anyone.” The event was covered in major newspapers across the United States. USA Today and other major newspapers even ran a photo of Reagan revving up a hog.13 On July 1, Beals and Forbes led twenty Harleys on a ride, which had been scripted by their ad agency, from the American Stock Exchange to the New York Stock Exchange, where a bike was parked on the trading floor for the day. On October 9—six months before the tariff was set to expire—President Reagan canceled the tariff. Reagan praised Harley’s recovery as a victory over the Japanese, further attributing the recovery to the spirit of the frontier West that his presidency was championing. Harley symbolized the revitalization of U.S. economic power that was possible through the Reagan-styled capitalist gunfighter myth.

The rhetorical impact of the event was stunning. The media jumped on Reagan’s performance, for it was perfectly scripted as a classic American comeback story: A company whose customers were the quintessential American frontier warriors had lost its way when bought up by a statist conglomerate. The company was salvaged by real gunfighter-cumentrepreneurs who understood the ethos. With help from an insurgent gunfighter-friendly president, the company was turned around and was again a proud and profitable company.

With this story line in place, Harley quickly became a central prop in Reagan’s storytelling. Harley’s consecration was made all the more meaningful by events that transpired after Reagan’s New York speech. The stock market crash of October 1987 signaled the end of the Wall Street financiers’ run as the nation’s gunfighter heroes. Wall Street’s version was untenable not only because of the outlandish corruption but also because the symbolism wasn’t entirely coherent. The new entrepreneurial spirit could not be centered in the heart of the “city”—in the midst of large, capitalist, bureaucratic institutions. To be truly effective, the new myth needed to incorporate some sort of frontier.

The Harley-Davidson Company, a Milwaukee concern with a heritage tied to the heartland and the West, was untainted by the crash. The company earned gunfighter credibility because it had somehow survived in the decimated Northern industrial region that had become known as the rust belt. As Wall Street and its yuppies were on their way out, and with them such symbols as BMWs and Rolexes, Harley was left standing as the most credible branded symbol for those wedded to Reagan’s ideology.

America’s Man-of-Action Stars Sign On

Following the Wall Street crash, Harley became the favored ride of Reagan’s Hollywood cronies. Not only Stallone and Eastwood, but also fellow men of action Arnold Schwarzenegger and Bruce Willis were featured in entertainment magazines on their hogs. These celebrity endorsements closed the circle that Forbes had initiated in the late 1970s, fixing Harley as the most potent symbol for Reagan’s gunfighter through its associations with these charismatic actors and their gunfighter films.

But the ultimate consecration of Harley as the favored ride of America’s new breed of men-of-action gunfighters came with the release of 1991’s hugely popular Terminator 2: Judgment Day (T2). Arnold Schwarzenegger (switching sides from his villain’s role in the prior film) plays the quintessential man-of-action gunfighter. He’s a machine, just like his molten metal enemy that has been sent back in time to terminate John Conner (the boy who would grow up years later to lead the resistance to save humankind). Yet he’s one of the good guys; he uses his violent powers toward just ends.

In the opening scene, Arnold does in some Hell’s Angels-styled outlaw bikers with paunches that signal they’re well past their prime. He steals one of their Harleys and rides off as a new-and-improved biker: a brutal and talented assassin whose violence is necessary to save Americans from totalitarian technologies. T2 was one of the most potent masculine myths of the era, and it all took place on a Harley!

These texts combined to reinvent Harley’s gunfighter into a new breed of man necessary to revive America. From a transgressive myth for men on the margins, Harley now carried a myth that helped men forge a connection with Reagan’s frontier call to revive American power. In so doing, these texts had separated the Harley bike from its old moorings in the outlaw biker world. Not only had the outlaw bikers all but disappeared, but so had the undesirable aspects of their ethos—the overt misogyny and in-your-face antisocial behavior and antibourgeois rhetoric. Harley’s new myth paid out handsomely as the United States hit a major cultural disruption in the early 1990s. When demand swelled for myths that imagined the revived authority of middle-class white men, Harley was perfectly positioned to respond.

Harley Becomes an Icon, Again

The new Wall Street–driven U.S. economy created extraordinary pressures and incentives that pushed corporate managers to expand markets, lower costs, and innovate better than competitors. By the early 1990s, as these financial pressures had spread around the globe, they carved out a new marketplace organized around the flexible networked organization, the knowledge-driven, winner-take-all labor market, and the aggressive reengineering of the firm.

Reagan had unleashed a juggernaut when he revitalized America’s frontier ideology. However, this next stage of American capitalism proved a poor fit with certain parts of his mythic construction. Reagan had vowed to advance a social conservative agenda aligned with the Christian right. In his vision, American ideology was to consecrate Christian ideals of morality, communicated through such touchstone issues as antiabortion and prayers in public schools. But Christian conservatism and the gunfighter myth were strange bedfellows, for gunfighters were not beholden to Christian morals—not in the American West of the nineteenth century, nor, as it turned out, in the “turbo-capitalism” at the end of the twentieth. Aside from a few highly publicized skirmishes—such as when Tipper Gore’s Parent’s Musical Resource Center lobbied the government to regulate lewd lyrics on heavy metal and rap albums—these issues fizzled.

Rather, an ideology that took up the first part of Reagan’s agenda—the free-agent frontier—proved to be the most functional and became favored by the majority of both political parties. The new economy required an ideology that sanctified dynamism, meritocratic competition, and absolute commitment to economic goals above all. Companies embraced cultural diversity to pursue global agendas, and they sought out the most talented and motivated employees, regardless of creed, gender, or ethnicity. The old idea of hierarchical command gave way to flatter structures and more flexible teams and alliances. Moreover, the new global free market was structured to court and amplify every consumer desire, be it for tabloid television, hip-hop couture, or even pornography. The neoconservatives in the Republican Party combined with Bill Clinton’s “New Democrats” to embrace the free movement of capital and labor, cultural diversity, feminism, meritocracy, and economic goals over military conquest.

The Anti-PC Myth Market

As this free-agent networked economy took hold, economic insecurity, mostly a blue-collar problem for the previous two decades, extended into the rest of the labor market. This economy created highly competitive labor markets and downward pressure on salaries for virtually every occupational category except for senior executives and highly specialized knowledge worker positions. The middle-class jobs on which men had previously depended for authority and prestige became unstable, subject to the same cost-benefit knife that had slashed so many blue-collar jobs during the 1970s and 1980s. And, like the economic dislocations in blue-collar work before, these shifts threatened men’s identities.

The result was a populist backlash led by men of European descent who had lived in the United States for several generations—a group whom the media came to call “angry white men.” These men had had their economic security and masculine status yanked from them. The most visible expressions were the explosion of shock radio, the paramilitary survivalist groups that together formed the militia or patriot movement, John Bly’s runaway best-selling book Iron John, and the Million Man March.

Populist observers pushed theories to explain these troubles, as well as myths to assuage these angry men’s pain. A cohort of social conservatives, led by Rush Limbaugh, used the economic turmoil of the day to paint a theory of cultural decay. Limbaugh was far and away the most influential cultural leader of the day, holding millions of self-proclaimed “dittoheads” under his sway in his role as a demagogue-like pundit on talk radio. He was eventually joined by fellow shock jocks such as Oliver North and G. Gordon Liddy. Limbaugh’s radio show climbed to number one in the United States, reaching more than 20 million listeners every week. A mostly male audience listened for hours at a time, much as people used to do in the pretelevision era. Limbaugh had to hire 140 people just to respond to the bagfuls of mail he received each day. His book The Way Things Ought to Be hit number one and spent many months on the New York Times best-seller list.

Limbaugh and his brethren effectively wove the shifting economic realities—the network economy, the free-agent winner-take-all job market, the increasing power of highly educated knowledge workers who were often immigrants and ethnic Americans—into a story that captivated those men dethroned by the new economy. Limbaugh argued that this devastating emasculation was caused by the “socialist-slash-communist” ideology of the liberal elites who controlled the federal government, the media, and Hollywood. In particular, Limbaugh singled out “whiners,” who selfishly berated how the country had wronged them rather than celebrate the nation’s inherent goodness: feminists (or “femiNazis” in Limbaugh’s memorable phrasing, signatures of which were Hillary Clinton and Anita Hill), civil rights activists (whose signatures were affirmative action, the Rodney King beating, and the O. J. Simpson trial), and environmentalists (the “tree-hugging” hypocrites who refused to acknowledge that they enjoyed the bounties that natural resources provided). In Limbaugh’s influential view, the success of 1960s agitators caused the anxieties felt by disgruntled American men.

Limbaugh advocated a return to patriotic values, which he located in post–World War II United States, when the nation was at its apex of power and prior to the 1960s upheaval. Limbaugh held up Reagan as a deity, one of America’s greatest leaders, because the president had fought against the 1960s culprits to rekindle America’s “traditional” values.

Part and parcel of this reactionary backlash was the spread of a nationalist fervor against the globalized competition for jobs. Americans, particularly the angry-white-men contingent, wanted to seal off the borders of the nation. Politicians as different as Jerry Brown, Pat Buchanan, and Ross Perot championed protectionist and isolationist “fortress America” policies.

The 1992 election of Bill Clinton (and his wife, Hillary) to the presidency set off a shock wave among these men. Clinton’s economic policies continued to push the market liberalization policies of the Reagan and Bush administrations. And to make matters worse, he, unlike his predecessors, didn’t cloak these policies in cultural conservatism. Clinton’s ideological agenda flaunted new-economy values—the antithesis of what the angry-white-men contingent desired. To these men, Clinton was one of Limbaugh’s liberal elites in good standing with his Yale law degree, a guy who not only enjoyed talking with blacks but also played a passable rhythm-and-blues saxophone. He came packaged with an assertive, liberal elite wife (also with a Yale law degree) who was determined to influence major policy initiatives rather than dabble in polite but tangential causes, as first ladies were supposed to do. Clinton began his presidency by pushing a “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy for gays in the military, searching for a “politics of meaning” with Jewish leaders, and holding national debates on racism, meanwhile acting as international statesman, a reverse of Reagan’s antagonistic swagger toward political foes.

Clinton’s election galvanized the opposition that Limbaugh and other social conservatives were stirring up. Consequently, Reagan’s call for men to stand up, like gunfighters, to Washington bureaucrats and the liberal media became all the more compelling. The gunfighter myth engulfed the periphery of American mass culture: in fundamentalist religion, in community organizations, in AM radio. Harley, with its well-established gunfighter credentials and ties to Reagan, was perfectly situated to become a central icon for this constituency.

Harley’s gunfighter myth, constructed with Reagan’s blessing, was ideally suited to work as a salve for these tensions. Harley served as the nucleus of a brotherhood of men joined to a conservative vision to restore “traditional” conservative masculinity (i.e., white, patriarchal, Christian, American) over the cultural free-for-all of the new global networked economy.

Men who could afford it flocked to Harley, seemingly overnight. The bike’s popularity soared among politically conservative, white, middle-aged, middle-class men—a group that had never before yearned for a Harley. The waiting list to buy a bike grew to a year or more, the prices of Harley bikes climbed to nearly $20,000, and the average Harley buyer soon earned around $80,000 in yearly income and was more likely to be in his forties than his twenties. The Harley-Davidson Company began to significantly outpace the Standard & Poor’s 500 in 1991 and hasn’t looked back since, achieving tremendous financial success as the central icon of the anti-PC myth market throughout the 1990s.

Harley-Davidson Learns to Coauthor the Myth

For decades, Harley-Davidson had studiously ignored its core customers. But, starting in the late 1970s, the company finally did an “if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em” flip-flop. Harley began to run ads that it hoped would mirror the brand as seen through the eyes of its core constituents—at the time the working-class white guys who identified so strongly with the outlaw bikers. In other words, while Reagan and his comrades were busy repackaging the Harley myth for a much more lucrative clientele, the company was still playing to its lower-class constituency.

Harley finally began advertising in Easyriders, and soon featured outlaw bikers in its mainstream print ads. In April 1980, Harley placed a five-page ad in Easyriders. The first page appeared on the right-hand page and functioned as an introduction, so that you’d have to turn the page to see the two-page spreads that followed. The first page was mostly black and white, except that on the top, giant red characters occupied a quarter of the page. Who knows if they actually said something in Japanese. Under these characters, in businesslike serif type about an eighth the size of the red characters, ran this copy: “They talk low. They talk custom.” The bottom half of the page shows the shadow of an eagle’s head, its carnivorous hooked beak a little open and ready for action. The print on the page bottom read, “Now, maybe they’ll stop talking.” The two gatefold photos that follow show a couple of new Harleys. The purpose of the ad was clearly to bait the vicious anti-Asian complex nurtured at the time among Harley’s working-class male constituents. Harley advertising continued to hold up a mirror to its patrons, doing its best to parrot their views. But since the semiotic stars aligned for Harley in the early 1990s, the Harley-Davidson Company has become much more adept at contributing to the brand’s myth.

The Anti-PC Poet. Harley understood that, in the minds of its constituents, the Harley myth was firmly lodged in the 1950s. Within the frame of the Harley mythology, the 1950s was the golden era of the United States. It was when the nation was at its most dominant, when men had secure jobs and were the unchallenged heads of nuclear families, and when the population was unthreatened by immigrants and women entering the work force. And this period predated the reviled 1960s social movements championed by the so-called liberal elites. It is certainly ironic, but also a demonstration of the power of myth to rewrite history, that a bike that supposedly represents libertarian ideals would locate its halcyon years in an era when the nation was the most conscripted to conventions!

Because Harley’s myth is about a brotherhood of gunfighters, much Harley mythmaking goes on at group events, especially the big rallies such as those held each year in places like Sturgis, South Dakota; Daytona Beach, Florida; and Laconia, New Hampshire. The company does its best to contribute to a richly evocative, revisionist history that places Harley at the center of the story.

A prime example of HDC’s creative branding efforts is the hiring of Martin Jack Rosenblum, “the Holy Ranger,” a folk musician and longtime Harley buff who holds a Ph.D. in English. Under his pseudonym, Rosenblum had published a book of poems that became popular among Harley enthusiasts. The Holy Ranger’s poetry provided Harley customers with a direct pipeline from bike to gunfighter ideals of manhood:

PRAISE OUR LADIES

These Harley women

straddle their choppers

with lustrous precision

& when packing behind you

with hands tucked under the

belt buckle at your waist a

man rides amidst powers of

awesome potential & the

bike actually lathers

like a stallion

bulging at the

barndoor. 14

Sensing a potent marketing opportunity, Harley-Davidson quickly hired Rosenblum as the official Harley historian and poet laureate. Then the company encouraged him to rekindle his musical interests. Rosenblum subsequently released several CDs of music filled with lyrics like the above. Rather than folk music—which for Harley possessed all the wrong hippie/ Beat connotations—Rosenblum abruptly switched to American “roots” music. Rosenblum’s cultural assignment was to build for Harley a musical genre that fit the 1950s focus of the mythology. He concocted an amalgam of electric blues and rockabilly-influenced rock of the 1950s and billed these styles as the “true American musical genres.” He has performed regularly at Harley functions, playing from these styles and using lyrics that he’s written as the poet of the Harley tribe.

Militia as Metaphor. In addition, Harley has become much more adept in its advertising, taking advantage of the political currents that influence their constituents. In place of its pedantic advertising of the past, the company began to draw on symbols that resonated with the anti-PC movement.

For Harley’s constituency, some of the most effective raw materials of the early 1990s came from another populist world that often intersected with the outlaw motorcycle clubs—the militia/patriot movement, a right-wing counterculture that had grown to sizable numbers mostly in the Pacific Northwest. These libertarian “patriots” argued against paying taxes and refused to obey national institutions unless they were in the Constitution. Members of patriot groups organized militias for projected future armed struggles to “save” the nation. They often took racist stands, spinning idiosyncratic readings of the Bible to support their views.

To tap into this symbolism, Harley produced a memorable print ad that depicted a lone cabin in the mountains of the West, with a Harley parked outside. The mountain cabin had become an icon of the militia movement, thanks to the Unabomber and Ruby Ridge incidents, both of which involved patriots holed up in mountain cabins. In fact, the Unibomber’s cabin had become a major tourist attraction. The Harley ad signaled the brand’s alignment with the values of the patriot movement, even if the company and its constituents refused to condone the patriots’ tactics.

Unveiling the Harley Mystique

Harley’s astounding rise in identity value in the early 1990s followed the same path as other iconic brands. Harley-Davidson motorcycles became a convincing symbol for a myth about manhood, a contemporary reinterpretation of America’s gunfighter. The brand gained iconic status because its myth anticipated the extraordinary anxieties experienced by a particular class of men who faced the American economic restructuring of the early 1990s.

The Harley myth felt authentic because it was so firmly grounded in the most credible populist world for championing gunfighter values—the outlaw motorcycle clubs. And because it was communicated with such charisma by film characters, actors, and an actor-turned-politician, the myth was particularly compelling. Harley had the right myth, with the requisite authenticity and charisma, and at the right time to lead culture.

The Harley mystique stemmed from the fact that its myth seemed to emanate organically from the bike. Its authors could not be sourced because they were too diffuse and because the usual suspect—the manufacturer—was only peripherally involved. Rather, the Harley myth was built over many decades by numerous authors. Initially, the mystique was the cumulative and unintended consequence of the motorcycle’s use by biker clubs as an emblem of their outlaw values. Later, filmmakers, journalists, and politicians picked up these bikers as raw cultural materials for their own varied agendas. In particular, Harley’s success hinged on the contributions by Malcolm Forbes, Ronald Reagan, and Reagan’s pantheon of gunfighter friends from the film industry. Without this helping hand from coauthors, Harley management would still be struggling to sell bikes to working-class guys.

Coauthoring an Iconic Brand

Iconic brands are usually built with advertisements: films produced by the brand owner. But two other potential coauthors—culture industries and populist worlds—can also contribute significantly to the brand’s myth. Harley is the most important American case of this sort of coauthorship. What can we learn from Harley’s success? The brand cannot be copied directly, but we can draw broader inferences about how coauthoring works.

Don’t Imitate Harley

Branding gurus continually praise Harley’s H.O.G. initiatives and advocate that companies should imitate Harley by building a brand community. All for naught. Followers form communities around icons (brands and otherwise) because the icons contribute to their identities, providing myths that resolve acute tensions. Followers sometimes gather together because doing so heightens the ritual power of the myth. “Community” isn’t an end in itself, one that brand managers can program by themselves. Rather, brand communities form when a brand provides a myth that is compelling enough to draw people together, on their own, so that they can amplify the myth through their interactions.

Harley’s customer group was organized by Harley enthusiasts in the 1970s, not by HDC in the 1980s. The company forcibly took over the riders’ organization—leading to considerable resentment among members at the time—because the group was hugely successful and the company recognized that it could be a tremendous marketing tool. Similarly, customer groups centered on Volkswagen and Apple—the other two poster children of brand community—were organized by enthusiasts who were so taken by the brand’s myth that they wanted to weave it more intensively into their lives. Brand communities never exist as ends in themselves. No amount of marketing attention to building a brand community will compensate for lack of a resonant identity myth.

Harley’s path to iconic status cannot be copied. While most iconic brands develop their myths via breakthrough advertising, Harley is a rare example of a different and rare evolution: a brand built autonomously by the culture industries and a populist world. Harley’s path cannot be replicated because Harley’s iconic power was never managed. The irresistible authenticity is a product of its ghost authors. Instead of imitation, we must push for broader lessons.

How Cultural Texts Affect Brand Myths

As consumers have become increasingly cynical about firm-sponsored communications, senior managers have eagerly shifted their attention to the other engines of identity value: the culture industries (via product placements) and populist worlds (via viral branding efforts). This shift makes sense. Society’s best mythmaking engines are found in these two locations, not in advertising.

But marketing has yet to crack the code on how to develop branded cultural texts, largely because the discipline continues to apply conventional branding models to the cultural terrain. When cultural texts are viewed as mere entertainment, rather than as myths, their potent identity value remains hidden.

The mind-share model treats cultural texts as a means to build up the brand’s DNA. Managers seek to align their brand’s associations with the right text to maximize fit and exposure. The viral model offers little strategic direction other than the old public relations saw to cause a stir, to get people talking. Pursuing the texts they believe will be the most popular—the most cool—managers try to get their brands into the mix.

These perspectives ignore that what consumers value most about these texts is the identity-buttressing myths that they perform. When cultural texts include a brand as a central prop, they can dramatically amplify and alter the brand’s myth. The Harley genealogy reveals two processes through which these texts can affect the brand’s myth: stitching and repackaging.

Stitching Texts. Cultural texts can draw a brand into an existing myth. The outlaw myth was not originally owned by Harley. It was developed by outlaw motorcycle club members, who sometimes rode Harleys as one of several acceptable big bikes. In the era of the Life magazine exposé and The Wild One, this myth was anchored to images of the scraggly bikers and their gear: leather, jeans, and big bikes. Not necessarily Harley. It was the Hell’s Angels news stories, Hunter S. Thompson’s articles and book, and in particular the film Easy Rider that stitched the outlaw myth to Harley.

Repackaging Texts. The culture industries can also reinvent the brand myth. The most important strategic question that one must answer to explain Harley’s success is one that the many management book treatises on Harley have never asked: How is it that a brand that provided extraordinary identity value to young working-class men by championing values that the middle-class found offensive could, a decade later, become one of the most prized possessions of middle-class executives?

Reagan and his comrades converted the rebellious gunfighter favored by down-and-out guys in the 1970s into a mythical hero: the man-of-action gunfighter whose violent bravado would save the country. Historical characters drawn into myth are malleable. Good storytellers can shape these characters to suit the story that needs to be told. Reagan grabbed the gunfighter and recast it to suit his political purposes. Harley, because of its gunfighter credentials and comeback story, proved to be the most useful symbol for Reagan to tell this story. The collective effect of Forbes’s freedom rides, Reagan’s “rescue” of the company, and the man-of-action celebrities who began to ride Harleys was to reinterpret Harley riders as heroic men-of-action—patriotic gunfighters committed to renewing the nation’s economic and political dominance by recharging its lapsing values (figure 7-2).

Culture Industry Texts Repackage the Harley Myth

To accomplish this alchemy, these new texts usefully “forgot” key elements of Harley’s outlaw ethos that conflicted with the new myth: the misogyny, the violence, the willful sloth, and the vitriolic dislike of authoritarian institutions. Moreover, the texts built up and reinterpreted other elements of the ethos. The libertarian politics, physical domination, and patriarchy were all kept and expansively reinterpreted to include economic and political dominance as well.

Repackaging texts don’t just disseminate the myth. They reinvent it by spotlighting and reinterpreting certain features of the myth while hiding others. Ad campaigns that have refurbished a fading brand myth to address a new contradiction—recall BBDO’s “Do the Dew,” Arnold’s “Drivers Wanted,” and Goodby Silverstein & Partners’ “Lizards” campaigns—work in much the same way. By tracing the path of the brand’s repackaging texts (culture industry and ads), we can explain how the brand’s myth gets transformed over time.

Collaborating with Coauthors

The source material for Harley’s initial outlaw myth was created by the outlaw motorcycle clubs that sprung up in the 1950s.15 Despite the high hopes of viral branding, however, populist worlds alone cannot create a brand myth. If the culture industries had not grabbed the bikers as source material for mythmaking texts, Harley would never have become an icon. The key question, then, is how should firms manage the brand when culture industries, outside the firm’s control, take control of the brand’s myth?

In the twenty-year period following Word War II, HDC offered an object lesson in how not to manage this collaboration. The Davidson family did its best to distance the brand from the outlaw bikers and their cronies. It was disturbed by the brand’s outlaw stories and wanted nothing to do with them. The family viewed the Harley as a grand touring bike for gentlemen and adventurous racers and was proud of the bike’s role in the war effort. To the owners’ mind, the media attention paid to outlaw bikers soiled Harley’s image. So Harley ads featured nuclear-suburban settings, and new Harley products like golf carts and three-wheeler bikes were geared to respectable, middle-class families. Harley even attacked the bikers’ use of “unauthorized” customized parts in their ads. These misguided efforts resulted in Harley’s missing a golden cultural branding opportunity in the 1960s. If properly managed, Harley could have easily joined Levi’s and Volkswagen as an iconic brand with wide appeal extending into the middle class.

When the Harley-Davidson Company finally decided to play along, it offered unimaginative and meek efforts to parrot the myth that the culture industries had produced. Such a policy basically ceded control of the brand to the culture industries. Harley was very fortunate that relinquishing control turned out so well, but this was pure luck. The culture industries could just as easily have lost interest or spun stories that worked against the brand’s myth.

In the 1990s, however, HDC became much more sophisticated at cultural branding. Instead of fighting against or parroting the influential cultural texts, the company began to elaborate on and tweak these texts to shape the myth to best suit its customers. For instance, the lone-cabin advertisement stitched relevant current events to the Harley myth in a way that a photojournalist’s shot in the newspapers was unlikely to capture. Similarly, the use of the Holy Ranger at Harley events extended the idea that Harleys are fighting actively for the rejuvenation of a “traditional” America, not just mimicking the culture industries (e.g., a screening of Easy Rider for the festival goers).