CHAPTER 9

Branding as Cultural Activism

ICONIC BRANDS ARE BUILT by cultural activists. Yet, while many companies would love to create a Nike, a Budweiser, or a Mountain Dew, most are organized to act as cultural reactionaries, whose practices are the opposite of the activism that is required. Managers typically view identity brands through the prism of the mind-share model. Mind share constructs a present-tense snapshot view of the brand, which blinds managers to emerging cultural opportunities. And mind share’s impulse to abstract—to yank the brand out of its cultural context—leaves managers arguing over adjectives that are largely devoid of strategic consequences. Managers routinely ignore the cultural content of the brand’s myth, treating this content as a tactical “executional” issue. As a result, they outsource the most critical strategic decisions on the brand to creatives at ad agencies, public relations firms, and design shops.

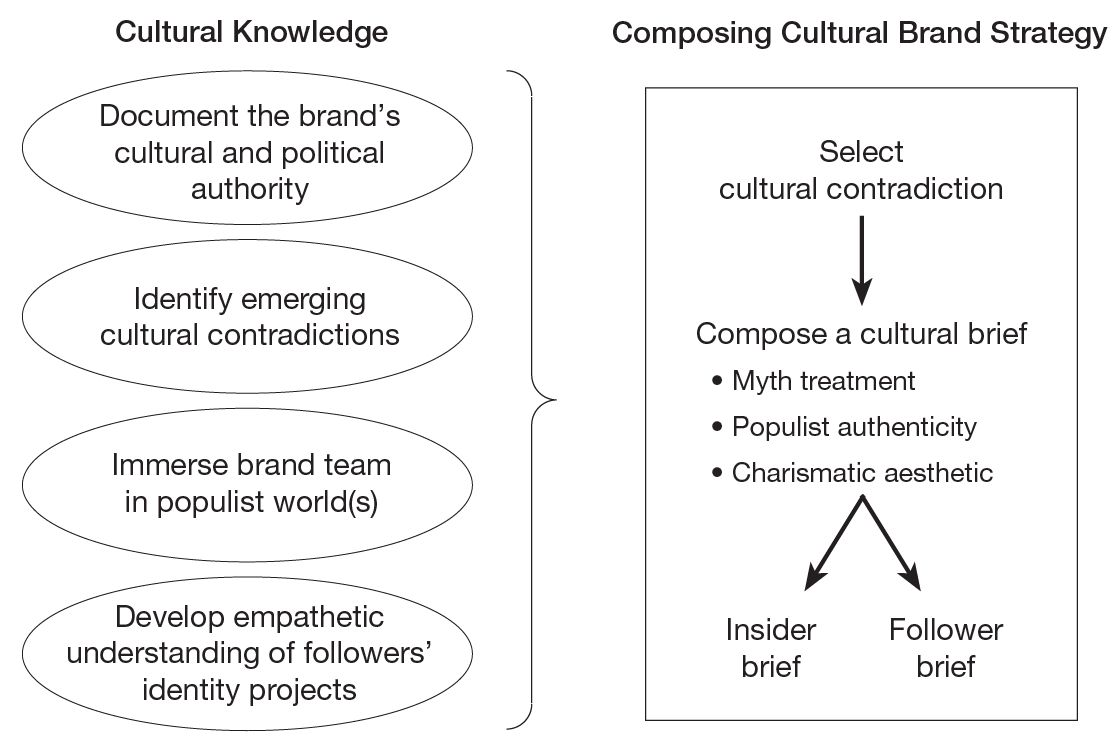

To systematically build iconic brands, companies must reinvent their marketing function. They must assemble cultural knowledge, rather than knowledge about individual consumers. They must strategize according to cultural branding principles, rather than apply the abstracted and present-tense mind-share model. And they must hire and train cultural activists, rather than stewards of brand essence.

Four Kinds of Cultural Knowledge

Managers require knowledge about their brands and their consumers to develop strategy. For cultural branding, this knowledge differs dramatically from the standard kinds of brand and consumer knowledge that managers now rely on to guide their branding efforts.

- Cultural knowledge focuses on the major social changes impacting the nation, rather than on clusters of individuals.

The Cultural Brand Management Process

- Cultural knowledge examines the role of major social categories of class, gender, and ethnicity in identity construction rather than obscuring these categories by sorting people into “psychographic” groups.

- Cultural knowledge views the brand as a historical actor in society.

- Cultural knowledge views people holistically, seeking to understand what gives their lives meaning, rather than as customers of category benefits.

- Cultural knowledge seeks to understand the identity value of mass culture texts, rather than treating mass culture simply as trends and entertainment.

Specifically, to build an iconic brand, managers must assemble four kinds of cultural knowledge (figure 9-1).

Inventory the Brand’s Cultural and Political Authority

Identity brands are malleable assets. Their growth depends in large part on whether managers understand the brand’s historic equities well enough to direct the brand toward the most advantageous future position. In the mind-share model the brand is understood as a set of timeless concepts. So the interpretation of its past efforts and direction into the future is a simple matter. Once the brand has earned valuable associations—the brand essence—don’t change anything! Consistency is the watchword, and brand stewardship is the mode of management.

For identity brands, the approach is different. We need to ask: What assets has the brand accrued through its historic activities that enhance (and also constrain) its future mythmaking ability?

Iconic brands build reputations, but not in the typical economic sense. Rather, successful brands develop reputations for telling a certain kind of story that addresses the identity desires of a particular constituency. In other words, iconic brands accrue two complementary assets: cultural authority and political authority. When a brand authors myths that people find valuable, it earns the authority to tell similar kinds of myths (cultural authority) to address the identity desires of a similar constituency (political authority) in the future.

Specifying the brand’s cultural and political authority provides managers direction to develop appropriate myths for the brand, and allows them to rule out myths that are a poor fit. If Volkswagen’s managers in the 1990s had understood that the brand had earned significant cultural authority in the 1960s to perform myths about individual creativity, and political authority to assuage a cultural contradiction that particularly afflicted the well-educated, urban, middle class, they could have directed creative partners toward the types of myths that would appeal to the new identity desires of the Bobos.

Develop Empathic Understanding of Followers’ Identity Projects

In conventional branding models, consumer research seeks to unearth deep insights into how customers think and behave. Researchers watch people in the act of consumption and interview them intensively to dig out tacit thoughts and feelings, all in the quest to reveal “consumer truths” that the brand can hang its hat on. Given the enormous attention paid to this kind of research in branding, it is noteworthy that I was unable to find a single example in which conventional consumer research contributed to the building of an iconic brand.

Because iconic brands create value differently than mind-share brands, they require a different kind of customer understanding. Great myths are grounded in an empathic understanding of people’s most acute desires and anxieties that, because they are generated by social forces, touch the lives of a broad swath of society. Resonant myths spring from an understanding of people’s ambitions at work, their dreams for their children, their fears of technology, their difficulties in building friendships, and so on. Notice that we are not talking about consumer behavior “truths” or emotional hot buttons—the usual language of consumer research. Indeed, the kind of understanding necessary for building identity value rejects thinking of the brand’s customers as merely consumers. Iconic brands address existential issues far beyond the usual benefits and behaviors associated with a product category. So consumer research must seek out the most significant identity projects of existing and prospective customers, and identify the most acute tensions that inflict these projects.

Further, this mode of understanding goes well beyond documenting people’s attitudes and emotions to acquire an embedded sense of what life really feels like if one were in their shoes. The kind of knowledge required to build an iconic brand is more like what an author requires to write a great novel or screenplay. Great authors are highly attuned to the world around them so that they see the world through the eyes of the other. The best ethnographies in anthropology and sociology achieve a similar result. Likewise, the most successful authors of icons have empathic antennae that connect with the critical identity issues that animate the lives of people they encounter. As a result, these authors create cultural texts that embody the society’s particular existential concerns.

Empathic understanding like this can’t be distilled and formalized into a research document. Nor can a manager gain this understanding indirectly. It cannot be outsourced to a research firm or brand consultancy, transferred to a research department, and finally distilled for those who are writing a strategy or creating brand materials. Icon builders reject conventional market research, and rightly so, for it lacks both the breadth and the depth of understanding required. Either managers must acquire this understanding firsthand, or they must gather and live with research that presents rich portraits of their customers’ lives, not glance through a Powerpoint summary of key findings.

For brands with an effective myth, managers need to cultivate empathic understanding of the identity projects of their followers and insiders. For brands in search of a new myth, managers should dig into the identity projects of prospects who best align with the brand’s cultural and political authority.

And ignore the brand’s feeders! Most customers of iconic brands are neither dedicated followers of the brand’s myth nor insiders tapped into the brand’s populist world. Rather, they are feeders: cultural parasites who use the brand for fashion, status, and community by feeding off the customers at the nucleus of the brand. Because their preferences are directly influenced by the desirability of the brand generated in the nucleus of followers and insiders, their preferences are of little use in guiding the brand strategy. Moreover, since feeders usually maintain a vague and idiosyncratic understanding of the brand, research that includes them will badly distort strategy. Nevertheless, because feeders often dominate sales, managers tend to build strategies from research heavily weighted toward how feeders understand and value the brand. Managers of iconic brands like ESPN, Nike, and Patagonia, never aim their strategies at these peripheral customers. Rather, they work to create the most desirable myth for their nucleus of followers and insiders and use this desirability as a magnet to attract others to the brand.

Immerse the Brand Team into the Populist World

Iconic brands rely on populist worlds as source materials for their myths. Populist worlds are typically far removed from the life experiences of the majority of the brand’s customers. Consequently, brand strategies guided only by a customer worldview can never make the necessary creative leap from identity desires to identity myth.

Iconic brands are usually built by people deeply immersed in the populist worlds that they draw from. At Nike and their agency Wieden and Kennedy, you’ll find inveterate jocks who live and breathe sport. In its halcyon days of Volkswagen Beetle advertising, DDB creatives drew from the New York City intelligentsia with whom they circulated. Thirty years later, the lead creative on “Drivers Wanted,” Lance Jensen, drew inspiration from his lifelong experiences inhabiting the indie bohemia. Mountain Dew’s lead creative Bill Bruce was a proto-slacker who worked in a record store before turning to advertising.

Similarly, Anheuser-Busch and DDB–Chicago have had great success with Bud Light, in no small part because both sides of the account are stocked with mostly Midwestern guys who share their target’s sense of humor because they’ve grown up in a similar cultural climate. “Whassup?!” on the other hand was outsourced to an African American director from Brooklyn. So, when DDB tried to take over the creative content, the campaign lost its verve.

Identify Emerging Cultural Contradictions

Cultural activism centers on identifying and responding to emerging cultural contradictions and the myth markets that form around these contradictions. Managers of incumbent brands must monitor how their brand’s myth works in the culture, tracking how changes in society influence the effectiveness of their brand’s myth. Likewise, managers seeking to develop new iconic brands must pinpoint emerging cultural opportunities.

To spot contradictions in society and isolate how these contradictions are addressed by myth markets, managers need to adopt a genealogical approach to the marketplace. Genealogical research documents emerging socio-economic contradictions, and then examines how the texts of the culture industry (films, ads, books, television programs, and so on) respond to these contradictions with new myths. Rather than static, microscopic research that delivers a snapshot of individual consumers, genealogy is macroscopic and dialectical.

Because most brand managers today rely on present-tense models of branding, they have little guidance in pushing the brand into the future other than keeping up with trends and trying to predict the next big thing. The false assumption here, which stems from the popularity of viral branding, is that brands must be first in the race to commodify new culture before it becomes hot. In the cases that I’ve studied, this assumption rarely holds. Rather, iconic brands play off cultural texts that the other culture industries have already put into play. In other words, iconic brands usually borrow from existing myth markets rather than create new myth markets themselves.

Brand Manager as Genealogist

In the mind-share model, the manager is anointed the steward of the brand’s timeless identity. The manager’s role is to identify the transcendental core of the brand and then maintain this core in the face of organizational pressures to try something new. In the cultural-branding model, the manager becomes a genealogist. Managers must be able to spot emergent cultural opportunities and understand their subtle characteristics. To do so, managers must hone their ability to see the brand as a cultural artifact moving through history. They must develop sensitive antennae to pick up tectonic shifts in society that create new identity desires. And they must view their brands as a cultural platform—just like a Hollywood film or a new social movement—to respond to these desires with effective myths.

Cultural knowledge is critical for building iconic brands, yet is sorely lacking in most managers’ arsenals. This knowledge doesn’t simply appear in focus group reports, ethnographies, or trend reports, the marketer’s usual means for getting close to the customer. Rather, such knowledge requires that managers develop new skills. They need a cultural historian’s understanding of ideology as it waxes and wanes, a sociologist’s charting of the topography of social contradictions, and a literary expedition into the popular culture that engages these contradictions. To create new myths, managers must get close to the nation—the social and cultural shifts and the desires and anxieties that result. This means looking far beyond consumers as they are known today.

Cultural Branding Strategy

Cultural branding strategy is a plan that directs the brand toward a particular kind of myth and also specifies how the myth should be composed. A cultural strategy is, necessarily, quite different from conventional branding strategies, which are full of rational and emotional benefits, brand personalities, and the like. Let’s return briefly to two iconic brands examined earlier—Volkswagen and Mountain Dew—to find out why.

Volkswagen Branding Strategy

In the early 1990s, as the company struggled to survive in the U.S. market, Volkswagen North America gave its longtime ad agency, DDB, one last chance to revive the brand’s once potent equity. DDB research identified that Volkswagen had carved out a distinctive mind-share position in the auto market as a brand engineered for great driving at a value price. In the 1980s, Volkswagen had developed new models—the Golf, Jetta, and especially the GTI—that performed more like their German brethren (BMW, Mercedes, and Audi) than the squishy handling of a Toyota or Ford. Since the mid-1980s, advertising had emphasized the excellent engineering and developed the tag line “the German Engineered Volkswagen.”

The new strategy pushed the communications from product features (e.g., tight turning radius) to benefits (Volkswagens provided a great driving experience for people who really enjoyed driving and appreciated the feel of the car on the road). After many months of deliberation to concoct the strategy and then to develop the best creative idea based on the strategy, Volkswagen and DDB produced the aforementioned disastrous “Fahrvergnugen” campaign. The campaign delivered precisely on Volkswagen’s strategy, communicating very clearly that Volkswagen built cars for people who really enjoyed driving and appreciated performance. Yet, while these odd ads made good on the mind-share strategy, the campaign managed to communicate an approach to life—sensory-deprived, mechanical, and isolated—that was virtually the inverse of what Volkswagen had historically championed in its myth.

After DDB was fired, a new marketing team at Volkswagen asked Arnold Communications to pitch the account. Like DDB, Arnold spent months doing research to devise a strategy. Arnold’s strategy was spurred by a J. D. Power survey, no doubt similar to what DDB drew from, describing Volkswagen owners as people who viewed driving as an experience rather than as a utilitarian means to get from A to B. According to the survey, Volkswagen customers liked to drive fast and appreciated the finer points of how the car performed. Hence, the agency developed an advertising strategy to communicate that Volkswagen is a car for people who love to drive. After months of debate, Arnold arrived at a mind-share strategy nearly identical to that used by DDB to produce “Fahrvergnugen.”

From this strategy, however, Arnold crafted an entirely different campaign, “Drivers Wanted,” which evolved into a huge and enduring success. Like the “Fahrvergnugen” campaign, “Drivers Wanted” also communicated the drivability benefits of Volkswagen. But the campaign was different in every other way. On the same product-benefit platform, Arnold built a myth about iconoclasts who are able to find ways to be creative and spontaneous in everyday life. What made the myth successful was that Arnold had located a way to update DDB’s Beetle myth about creativity in a way that worked in the social milieu of the United States of the late 1990s.

Mountain Dew Branding Strategy

Consider also PepsiCo’s strategy for Mountain Dew in 1993. The strategy emphasized the experiential qualities of consuming the brand, exhilaration and excitement, which were delivered by its sugary, caffeinated buzz: “You can have the most thrilling, exciting, daring experience but it will never compete with the exhilarating experience of a Mountain Dew.”

Guided by this strategy, PepsiCo and BBDO bet the brand on the disastrous “Super Dewd” campaign, in which a cliché African American cartoon character stomps around the inner city, chugging Mountain Dew while skateboarders and bikers scoot by. The action was exhilarating, to be sure. But the story didn’t fit at all with Mountain Dew’s cultural and political authority, which was the championing of wild-man ideals for nonprofessional rural white guys.

At the same time, the marketers created a side campaign for Diet Mountain Dew—a campaign that later became “Do the Dew”—from the same strategy, with the additional directive to encourage trial of the diet drink. Unlike “Super Dewd,” the “Do the Dew” campaign tapped the most viable cultural opportunity for Mountain Dew in the early 1990s: a new wild-man myth that combined the cultural raw materials from the emerging extreme sports populist world with ideas borrowed from Hollywood’s slacker myths.

Like Volkswagen, identical strategies produced very different campaigns with diametrically opposite results. Mountain Dew’s strategy failed to rule out a grossly ineffective campaign and, likewise, provided no direction to BBDO creatives in devising a winning campaign. In 1993, there were literally hundreds of expressions of “thrilling, exciting, daring experience” available in American culture. BBDO creatives might have drawn on any of these expressions to craft Mountain Dew ads. The strategy document gave no clues as to which were better expressions.

PepsiCo and Volkswagen spent many months with their agencies debating the proper adjectives to attach to their brands, adjectives that would distinguish the brands from their soft drink and auto competitors. Yet, in the end, the selected concepts provided guidelines so vague and imprecise that campaigns from the most brilliant to the most mediocre could be evaluated as on-strategy. What marketers have been calling a brand strategy for decades is not doing the work that strategy is supposed to do: forcing tough decisions by specifying criteria that distinguish better choices from worse ones.

The single most debilitating mistake that managers can make in regard to the long-term health of an identity brand is to develop a strategy so abstract that it yanks the brand out of its social and cultural context. Product design and benefits are the platform on which myths are built. A wide variety of myths can be built atop any product-benefit platform, and most of them are worth little to consumers.

What, then, is a strategy for an identity brand? Cultural brand strategy must identify the most valuable type of myth for the brand to perform at a particular historical juncture, and then provide specific direction to creative partners on how to compose the myth. Drawing from the cultural knowledge described above, a cultural branding strategy should include the following components:

Target the most appropriate myth market. With knowledge of the country’s most important existing and emerging myth markets and the brand’s cultural and political authority, managers look for the best fit. The most opportune myth market is the one that the brand has the most authority to address. Mountain Dew’s equity made the slacker myth market a perfect choice, while the Indie myth market was a natural fit for Volkswagen given its cultural and political authority.1

Compose the identity myth. Managers shouldn’t usurp the role of their creatives, but they must give specific direction on creative content if they are to play a significant strategic role. The first step in composing the myth is to prepare a myth treatment: a synopsis of the myth that describes the identity anxieties the myth should address and the way in which the myth will resolve these anxieties. Next, managers must describe the populist world in which the myth will be located, and the strategy for the brand to develop an authentic voice within this world. To maintain legitimacy, the executions of the myth must aim in part at the insiders who control the populist world that the brand inhabits. Brands win this authenticity with performances that express the brand’s populist world literacy and its fidelity to the world’s values. Finally, managers need to work with their creative partners to develop the brand’s charismatic aesthetic, namely, an original communication code that is organic to the populist world.

Extend the identity myth. When a brand performs the right myth targeted at the right myth market, consumers jump on board, using the product to sate their identity desires. They come to depend on the brand as an icon and remain fiercely loyal, but only as long as the brand keeps the myth fresh and historically relevant. Once established, myths must evolve creatively and also weave in new popular culture in order to remain vital.

Reinvent the identity myth. Even the most compelling identity myths will eventually falter, not because competitors attack, but because societal changes drain their value. The seemingly rock-solid value of a brand’s myth in one year can come unglued the next. Socio-economic and ideological shifts reconfigure the identity desires of the nation’s citizens, sending them searching for new myths. These cultural disruptions create extraordinary opportunities for innovative new identity brands while also presenting treacherous hazards for incumbents.

Even the most successful brands routinely struggle to understand the cultural disruptions that send their brands into tailspins. Witness Volkswagen’s two-decade-long struggle to regain its iconic stature and Budweiser’s dead-end experiments that stalled the brand for most of the 1990s. Other brands, like Miller, Levi’s, and Cadillac, have yet to recover.

Brand Manager as Composer

Brand managers must act as composers of the brand’s myth. Too often, the job of the brand manager is reduced to adjective selection—the management of meaningless abstractions. As cultural activists, managers treat their brands as a medium—no different than a novel or a film—to deliver provocative creative materials that respond to society’s new cultural needs. While they must leave the actual construction of the myth and its charismatic voicing to creative talent, managers must become directly involved in the composition of the myth, or else they give away the strategic direction of the brand.2

The Cultural Activist Organization

Marketing organizations are today dominated by spreadsheets, income statements, reams of market data, and feasibility reports. The rationality and pragmatism of the everyday business of marketing smothers cultural activism. Moreover, the breeding ground for brand managers—M.B.A. programs in business schools—conscientiously socializes managers into a psychoeconomic worldview that runs directly counter to the cultural point of view needed for identity brands. Many business schools marginalize social issues as the domain of not-for-profit ventures and treat the texts of the culture industries superficially, if at all. Most M.B.A.’s leave their programs without even a rudimentary ability to evaluate an ad from a cultural perspective.

Iconic brands have broken out of this rationalized mind-set to make contact with the nation’s culture. They are exceptions to the rule, led by the intuitions of ad agency creatives and the occasional marketing iconoclast. Because companies have not nurtured a cultural perspective and the talent that goes with it, the primary architects of iconic brands have been copywriters and art directors. Not surprisingly, the members of the brand team with the greatest cultural competencies take the lead. As a result, cultural strategies have evolved haphazardly by the chance engagement of talented creatives, rather than through the consistent deployment of a brand strategy.

For brand owners that seek to build iconic brands, the challenge is to develop a cultural activist organization: a company organized around developing identity myths that address emerging contradictions in society; a company organized to collaborate with creative partners to perform myths that have the charisma and authenticity necessary to attract followers; a company that is organized to understand society and culture, not just consumers; and a company that is staffed with managers who have ability and training in these areas.

Mind-share branding is today slipping out of favor even among its most loyal stalwarts. And commingling brands with culture seems to be in. Procter & Gamble, The Coca-Cola Company, and Unilever all have made significant gestures of late to move in new directions, often mentioning Hollywood as the most likely destination.

In a speech to the Publicity Club of London, Niall Fitzgerald, then chairman of Unilever, proclaimed that the “interrupt and repeat” model of advertising is in decline, and so marketers can no longer push “messages and memorability into the skulls of the audience.” 3 In place of mind share, Fitzgerald sees advertising moving into the space occupied by other culture industry products like film: “Today we should conceive and evaluate our brand communication as though it were content—because today, in effect, that is what it is. We are in the branded content business.”

Fitzgerald is certainly right. Marketing companies can no longer ignore that consumers have become tremendously cynical about advertising and can now act on this cynicism with technologies like TiVo, which allows them to edit out ad exposures. Instead, advertising is looking more and more like entertainment. Madison Avenue and Hollywood are becoming incestuous partners.

But how should companies, long enamored by mind share, proceed? Fitzgerald seems to suggest that branded content is a new-to-the-world proposition. But, as this book makes clear, the most successful identity brands have long focused on delivering branded content, at least since the beginning of the television age in the mid-1950s. The extraordinary successes of Marlboro and Volkswagen in the 1960s; Coke and McDonald’s in the 1970s; Nike, Budweiser, and Absolut in the 1980s; and Mountain Dew and Snapple in the 1990s were all the result of branded content. So managers interested in new branding models would do well to glean some lessons from their predecessors rather than try to reinvent the wheel.

Fitzgerald’s provocations beg the question: What branded content? If brands merely deliver entertainment like most culture-industry products, they will be handicapped from the start. We live in a world oversaturated with cultural content, which is delivered not just by the traditional culture industries (film, television, magazines, books, and so on) but also increasingly by video games and the Internet. How can a thirty-second ad compete with a film or rock concert in terms of entertainment value? Or, alternatively, why would customers seek out a film when the plot is stilted by commercial sponsorship?

The greatest opportunity for brands today is to deliver not entertainment, but rather myths that their customers can use to manage the exigencies of a world that increasingly threatens their identities. To do so, companies would do well to follow the lead of the most successful brands of the past half-century rather than throw their marketing budgets at Hollywood. Brands become cultural icons by performing myths that address society’s most vexing contradictions.