APPENDIX

Methods

Building Theory with Cases

Theory is sometimes a dirty word in management circles, associated with arcane abstractions that are irrelevant to real business decisions. But managers do require theories—simplified models that guide decisions—to manage. The challenge is to build theories that speak directly to management issues rather than tangential abstractions of only academic concern. In this book, my goal is to build a theory that explains how brands become icons, a central concern of many brand managers. To this end, I followed the time-tested approach used often in organizational studies and other social sciences: building theory with cases. I began by drawing on existing theories in the culture-focused academic disciplines to specify the general contours of iconic brands. I then selected cases of iconic brands that would allow me to build a new brand strategy model. I found it necessary to devise a new empirical method for studying these brands—what I call a brand genealogy—because previous research has not examined brands from a cultural perspective.

Building a new theory requires many iterations of tacking between the cases and the general cultural theories that informed the research to search for patterns. Through this comparative process, I built a new model that I call cultural branding strategy. Along the way, I threw out several dozen tentative models that I rejected either because they didn’t quite map onto the case data or because they didn’t make sense in relation to existing cultural theory. The details of this process follow.

Case Selection: American Iconic Brands

I developed the theory through case studies of some of the most successful identity brands of the last half century. These are the iconic brands, or brands whose identity value is so powerful that they become accepted as consensus symbols in American culture.

I first identified those brands whose value stems primarily from storytelling rather than how well the product works. I eliminated from the sample universe those composite brands whose value is strongly driven both by storytelling and by other factors, such as superior product performance, innovative product designs, advanced technologies, or a superior business model. Apple, Polo, and BMW are examples of the types of brands that I eliminated. To isolate how cultural branding works, it was important to study brands for which cultural branding is the predominant branding tool and, thus, for which it is difficult to construct alternative explanations for the brand’s success.

I was particularly interested in studying brands whose value waxed and waned over time. This kind of variance gave me more interesting and difficult data to explain and required that I pay close attention to historical changes. The brands I worked with most extensively—Mountain Dew, Volkswagen, Budweiser, Harley, ESPN, and Nike (I don’t report on Nike in the book, because of space limitations)—are from six industries, with very different histories, competitive situations, and consumer bases. The historical investigation nevertheless revealed that the brands have definitive commonalities that led to their success. These commonalities, their implicit cultural branding strategy, form the core of this book.

While the principles of cultural branding apply widely (with some necessary adjustments for cultural differences across countries), I chose to focus on American brands for two reasons. First, from a research perspective, the brand genealogy method requires an intensive immersion into social and cultural history. Including brands from other countries would have lengthened the project by years. Second, from an expository perspective, it’s much easier for me to orient the reader to the cultural branding principles using similar historical material in each case. This redundancy allows me to show patterns across these brands, as each brand engaged the same historical forces in different ways to create valuable myths.

Data: Films

Cultural branding works when the brand’s stories connect powerfully with particular contradictions in American society. Consequently, the only way to study cultural branding is to study the stories that the brand performs over time.1 For reasons described earlier, television ads provided the core empirical data for this book, dominating four of the six brands that I analyzed extensively. At first glance, this emphasis may seem myopic. After all, most firms execute their branding strategies comprehensively across product, customer service, distribution, and more. It’s never just ads. But this choice makes sense, because my focus is on identity value. And identity value is created primarily through storytelling.

Sponsored films—advertisements broadcast on television, in theaters, and, more recently, via the Internet—have been far and away the most effective means for building iconic brands. For the cultural branding process to work, the brand must perform stories. And for fifty years, television advertising has been the best storytelling vehicle available. There are exceptions, to be sure. Service providers and retailers, like Starbucks, for example, can effectively use their store space and customer interactions for storytelling purposes. But, for all the cultural brands I’ve studied, the point of difference—what made the brand so desirable—was film, usually in the form of television advertising. Identity brands must be very good at product quality, distribution, promotion, pricing, and customer service. But these attributes are simply the ante that marketers must pony up to be competitive. They aren’t drivers of business success. Identity brands live or die on the quality of their communications.

This argument runs against the grain of the current marketing zeitgeist, which has again forecasted the death of advertising. Certainly, conventional advertising—ads that seek to persuade people to think differently about product benefits—are becoming less effective as media get more fragmented and as audiences become more cynical about marketer’s claims.

But cultural branding is different. Iconic brands perform ads that people love to watch. With the advent of the Web, customers search out these ads on Web sites, download them, and e-mail them around the world, watching them over and over. These ads don’t wear out, at least not easily. Some companies I’ve studied have even relaunched favorite ads, much as a well-liked film can be re-released.

Further, advertisers are now aggressively developing alternative media for their films: in theaters, on the Internet, in dedicated cable channels, and in retail spaces. Even if network television fades under the effects of media fragmentation and TiVo, iconic brands will simply find other venues to tell their stories through film. Media may shift, but the principles for constructing valued myths are enduring.

For the six brands I studied, I gathered historical reels of brand advertising extending back decades. These were comprehensive reels, not highlights. The number of ads I analyzed ranged from sixty to several hundred for each brand. I developed detailed narratives that explained the cultural fit (or lack thereof) between the ads and American culture and society, pushing to explain the major ups and downs of the brand throughout its history. Although I present an edited, highlights version of the analyses in the chapters for the readers to follow, each brand genealogy required much more detailed analysis. The complete analysis included most of the ads produced rather than just the most influential. This kind of attention to detail allows the researcher to plumb the nuances of strategy that explain success versus mediocrity. With more superficial data, these nuances would be invisible.2

Method: Brand Genealogy

I developed a new method for studying brands by adapting the most influential analyses of mass-culture products found in the various cultural disciplines. 3 By tracing the fit between the text and changes in American society and culture and by following how these resonances ebb and flow over time, these analyses explain why important cultural products (e.g., Western films, romance novels, Elvis Presley, and Oprah Winfrey) resonate in the culture at a particular historical juncture.

The brand genealogy method begins by assembling a close chronological interpretation of the content of the brand’s advertisements. I paid particular attention to ads that managers (and occasionally the trade press) have told me were particularly successful or, alternatively, were tragically flawed. Most of the time, however, I had to infer what elements made the ads successful. To do so, I looked at the patterning of different elements in the ads over time. Successful elements of the ads are those that the creators keep in the mix and try to elaborate on over time. Unimportant or weak elements are eventually tossed out as the campaign develops.4

I overlaid this chronology with changes in the identity value of the brand, which I estimated from archival reports and managers’ recollections of sales, share, and price premiums (figure A-1). This is the history that I want to explain with my analysis: Why did particular advertisements resonate perfectly in American culture, leading to great increases in brand equity, whereas others sent the brand into a tailspin?

Data to Be Explained: Why Ads Resonate or Disconnect

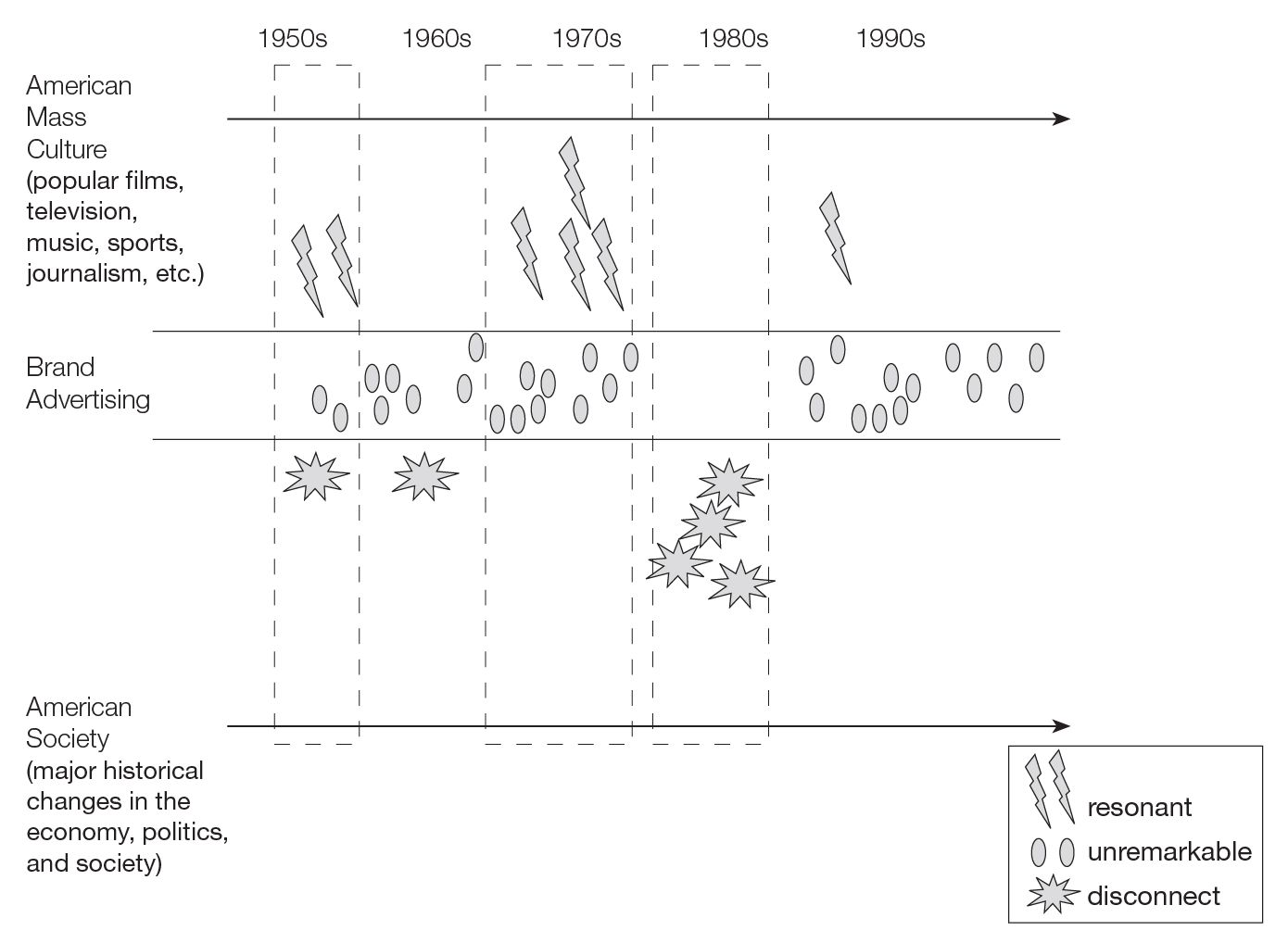

Alongside the patterns of advertising, I traced the history of the most influential mass-culture products relevant to the brand’s communications. I also looked at the relevant social, political, and economic history that might affect how the brand’s stories resonated (figure A-2).

The brand genealogy method consists in moving back and forth between these three levels of analysis: a close textual analysis of the brand’s ads over time, a discourse analysis of other related mass culture products as they change over time, and a socioeconomic tracking of the major shifts in American society. The goal is to explain why particular stories generate extraordinary resonance whereas the vast majority fall flat and some are veritable disasters. For each important ad, or set of related ads, I tacked back and forth between the ads, popular culture, and society to construct an interpretation that describes the fit. I continued with this process until I had constructed an explanation that made sense of all the data.

Systematic Comparison

Robust theories are built through systematic comparison of cases to identify patterns. Any individual case can be explained in several ways, each of which makes equally convincing sense, given the available data. On the other hand, it’s much harder to construct an explanation that works equally well across several cases. As a result, the analyst can more readily rule out alternative explanations. In management studies, the comparative case method has produced some of the most influential books in recent years, including Built to Last and The Innovator’s Dilemma. There’s no reason that brand theories cannot be similarly rigorous in their construction.

Linking Advertisements to Mass Culture and Societal Change

A second problem with anchoring on celebrated individual cases is that any given case always has some idiosyncratic qualities that can only be identified through comparison. Take Harley-Davidson, a cause célèbre used in a raft of books. My research reveals that previous analyses have badly misinterpreted why Harley was successful. I have discovered that the pervasive emulation of Harley is unwarranted because the Harley brand evolved like no other and is virtually impossible to imitate. When viewed with the benefit of comparison to other cases, Harley is clearly one of the worst brands for managers to use as a model (see chapter 7).

The Theory-Building Process

Academic theory building is based on systematic skepticism. A researcher challenges conclusions with data until the theory proves that it can handle all comers. Rather than selling a favored theory, he or she seeks out strong challengers and subjects these theories to an empirical test with sufficiently detailed data. The best theory wins. Throughout this book, I compare cultural strategy to the two most important challengers, mind-share and viral models, to demonstrate that my theory provides a superior explanation for the success of the iconic brands that I study. I began with Nike, Mountain Dew, Volkswagen, and Budweiser. And then, to push the boundaries of the theory, I added two cases (Harley and ESPN) in which the brand was built without much help from advertising. The ability of the cultural branding model to explain how these brands became so desirable increases confidence that the model is robust. Figure A-3 shows a simplified version of the theory-building process.

Deductions from General Cultural Theories

As an applied discipline, marketing works under the umbrella of the great intellectual traditions of the past century—from economics and psychology to sociology, anthropology, and, more recently, the humanities—adapting knowledge of these fields to the peculiar tasks of marketing. Good applied theories are rarely inducted out of the blue. Rather, they are informed by the more general theories in the fields from which the discipline draws. These general theories are used as a flexible tool kit, pulling out the appropriate ideas, amending them, and combining them to fit the problem at hand.

To build a theory of cultural branding, I drew selectively from a variety of fields that specialize in cultural analysis: cultural sociology, cultural anthropology, cultural history, and various other humanities disciplines that are often called cultural studies. These disciplines have developed powerful conceptual tools that, with some modifications, usefully inform how cultural branding works. I have placed this paper trail in the endnotes so that the book is easier to read.