Chapter 7

Sacrifices and Trade-offs

As I’ve discussed, you are bound to encounter some sacrifices and trade-offs on your life straightaway, putting a curve or a twist where you hadn’t thought one would be.

Dorian Mintzer, PhD, has over 40 years of experience as a therapist, life/retirement transition coach, money and relationship coach, consultant, writer, speaker, teacher, and group and workshop facilitator. She works with individuals and couples who are dealing with “what’s next?” and want help to develop a sense of well-being as they navigate the “second half of life.” (Dorian can be found at http://www.revolutionizeretirement.com.)

When I interviewed Dori, we spoke about how many transitions there are in an average life and how much we might have in common.

George: Do we really have that much in common?

Dorian: In a simplistic way, what we have in common is that all of us, if we’re lucky, are going to get older and, in the process, experience multiple transitions, changes, and loses throughout our life. There are always “surprises” and “curveballs” that we have to deal with. What makes each person unique, however, is how we handle and cope with these experiences. People vary in how they make sense of and frame the experience and how resilient or not they are. I’m often impressed with the variety of how differently people experience similar events. I believe that our response is partly influenced by how we’ve handled earlier transitions, changes, and loss and what we learned—or didn’t learn—from those experiences.

If you’re financially secure, they may only be small bumps in the road. However, regardless of financial status, these twists and curves around timing, family, professional, health, personal, or a combination of issues could be important to your future quality of life, retired or not.

This chapter will help you navigate through these encounters with soft and very hard choices, both of which can involve sacrifices and trade-offs.

What do I mean by sacrifice? I mean letting go, temporarily or permanently, of something you have held dear until now but that seems to be included in the price for achieving what you now think is most important in the short or long term.

Charlotte and Bill, both 71, had thought they would be fully retired by now. Bill did retire. Then he fell ill and, although the couple had medical insurance, their portion of the bills took nearly one-quarter of their retirement savings. Even after he recovered his health, Bill had extended periods of despondence. For quite a while he wasn’t employable. This wasn’t what he had planned when they created their long-term retirement plan. Charlotte sacrificed her own retirement expectations, continuing to work full-time as she had for years. They could easily live on her income as long as she had no health issues and a job, but they couldn’t really replenish their retirement savings.

Elton and Laqueta, ages 56 and 54, had their children late in life. The four girls were 17, 16, 14, and 13. Elton had worked at the plant for 30 years on the day he learned the plant was being shut down permanently. Until that morning, retirement had been on the near horizon. The couple had talked about it often. Getting a good job at another plant would require the family to move to another state. A local competitor also offered him a job, which meant they wouldn’t have to move, but at much less money. They had to evaluate their options. Should they move the girls to take the new job elsewhere or remain where they were but make far less money? In the end they decided to make the five-year sacrifice and stay where they were. Laqueta would go to work to make up some of the lost income. The girls, in what their parents saw as essential years, could stay in a stable, familiar, and supportive neighborhood and school environment. As the youngest approached age 18, the parents would take a hard look at what was best for just the two of them at that point and then make whatever changes were necessary.

What do I mean by trade-offs? I mean there are two or three things you want. You are going to have to choose between them because there isn’t the money or time or energy for all of them at this juncture in life.

Maybe Danielle, age 68, and Matt, age 69, should have seen it coming, but they did not. They had worked together in the advertising business they had started, lived in their community for a long time, raised their kids and seen them off to their own lives, and been prominent in the business and social communities. They had grand retirement plans that included selling the business to one of their most senior employees. Unfortunately, in a recent economic downturn of epic proportions for their region, their clients stopped advertising. They didn’t simply cut back but outright stopped. Even with some cash reserves, having no revenue was a huge problem when they also had a combination of a bank loan payment, monthly payments on the office building, payroll for the employees, and ongoing costs like insurance, website support, and the memberships and events in their town that made them prominent players. The couple wanted the business back on track and themselves back on the retirement track. Danielle and Matt were deeply attached to being business owners, partners, and in charge. The financial solution that presented itself was an investment in their company by a large statewide firm. They would no longer have majority, much less total ownership. On the other hand, the business would have the resources to survive almost indefinitely and the two could continue to work their way back to prosperity and their retirement. They were face-to-face with the biggest trade-off of their working lives: Sell a majority interest in the business to give it a secure future or remain in full control of their much less secure organization.

We could devote significant attention here to anticipating all possible types of situational, expected, and unexpected sacrifices and trade-offs. I’d rather not do that because I think you already get it. What I would like to do, however, is provide you with an alternative approach to help you manage these trade-offs. That’s what the rest of Chapter 7 is all about.

A TEMPLATE TO ASSIST WITH DECISIONS, SACRIFICES, AND TRADE-OFFS

Sacrifices and trade-offs may be an essential part of crafting your future together with inspiration and opportunity as you go along. If the answers to high-quality questions don’t include the possibility of at least short-term sacrifices and trade-offs, there could be something wrong with your questions and answers or both.

“There” (as in Finally Got There to stay and don’t have to face any of this ever again) may need to be one of the sacrifices. And trade-offs are already an essential part of many smart, informed decision-making processes.

Remember our earlier conversation and work about how the quality of the question drives the quality of the answer? It’s true, and we’re going to work with that concept again.

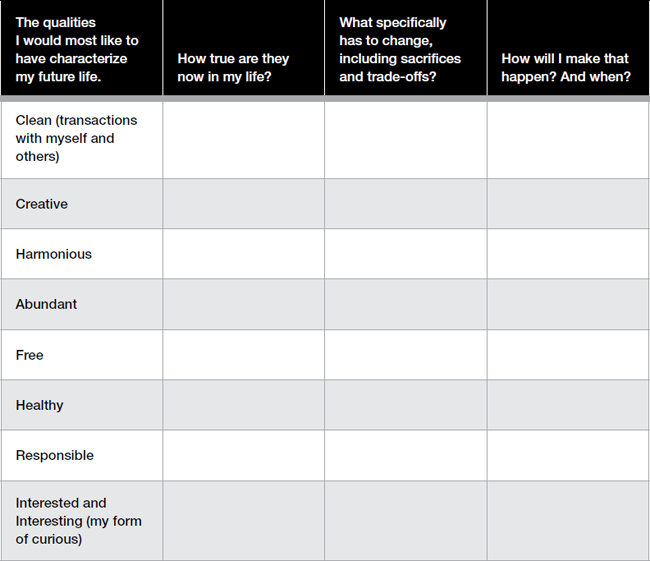

Here is my own current template. It doesn’t change very much or very often. Not that it can’t change, but I’ve been doing this for so long the winnowing process is settled, at least for now. You don’t need to know exactly what I mean by each characteristic word to get the picture. Doing this leads us to use our perspective abilities and see the big picture about ourselves and our lives. Remember that the characteristic words in the left column are my own, for example purposes, and should be replaced by your own. You’ve already begun answering the questions—and are on the way to completing the template—if you really did the work in each of the preceding chapters. Figure 7-1 is my template for my purposes and choices in my life.

Figure 7-1. George’s template.

Reader Exercise

Here is your own blank template (see Figure 7-2). The information we are seeking, for now, is limited to the left column only.

Stop and take some time to decide what qualities you would truly like to characterize your near-term future life. If you need to discuss with someone else, please do so BUT remember that in the end, the characteristics need to be of your selection, not the other person’s. As I mentioned in the last chapter, you should find someone who is perceptive and candid and will provide honest feedback to you. Take your time. It has to get done, but this is not a power exercise in which success is beating the clock or leaving no spaces unfilled. This is your life we’re talking about. It’s important to me . . . and to you.

I had to make a decision here. Was I going to give you the whole template at this point OR was I going to only show you the left column? The upside of only showing you the left column is that I don’t run the risk of losing your attention or having you get way ahead of where we are in this exercise. The downside of only showing you the left column is that your characteristic qualities are disembodied from the emergence of the short-, mid-, and long-term pieces of your retirement and life plan.

I’ve chosen to give you the complete template and ask you to work on the left column only. After that’s done and you are satisfied with its contents for now, please feel free to work on the rest of the template.

At this point in the book and our process, you should begin to see your retirement or life plan—all three perspectives—begin to come together in your head.

While we’re at it, knowing that you will shortly be moving across the template and your plan will begin to emerge, let’s revisit some of the most important information and high-quality questions we covered earlier in the book.

•What in your life that you are good at now will serve you well in the future? What will not? Samantha has been instrumental all through her husband’s medical career and medical practice build. Her skill at drawing new medical talent into her husband’s professional community is legendary. All of their community friends are beginning to retire and move away. Her husband is talking about it also and doesn’t expect to replenish his local contacts. How will these skills help her in the future? How could they get in her way?

•What roles that you now occupy will serve you well in the future? Which will not? Which have already come to an end but you are pretending they have not? Lynn is a professional woman and a really involved, dominant mother. She and her husband have one daughter, now age 24, who is just getting around to moving out of her parents’ home. The daughter never made the connection between her major and future work satisfaction/employability until after she graduated. Lynn is now 55. How long will the dominant role of mother continue to serve Lynn and her daughter well? When could it begin to get in her way and how?

•Who in your life now will serve you well and vice versa in the future? Who will not? Which of these relationships represents a larger network of connections that will need to be nurtured or eliminated? Terry is still working more than full-time and loves it. He has lots of friends, so many he can hardly keep up with all of them. His best friend has announced his retirement and rededication of his life to improving his golf score. Also a lawyer, he hopes that he can leave all talk of law behind in retirement. The two men had a lot in common until now, but their life roadways are beginning to diverge rapidly. How valuable is this relationship likely to be to Terry in the future?

•Which physical objects are you hanging on to from habit and a reluctance to let go? Which physical objects will fit into your future and serve you well? The same goes for relationships. Which will be most useful to you in the future?

•When she was a girl in the 1940s and 1950s, George’s mother collected demitasse cups. When she died, George inherited the collection. They have been packed away for many years. George is sentimental about the cups. He doesn’t have a place to display them. His children and grandchildren don’t want them. He feels as if he would be throwing away his mother’s girlhood by disposing of them. How well are these demitasse cups likely to serve George in the future?

It’s time to take a kind of inventory. As we progress through our lives, many of us have a decreasing capacity to haul an excessive number of physical tokens and history around with us.

There is a huge danger here that we will leap into action, abandoning and tossing aside without reflection or common sense. Excessive action here looks like no criteria, little thought, and a kind of temporary obsession.

There is also a huge danger here that we will feel totally overwhelmed and defeated even before we begin. Insufficient action here looks like slumping in a chair and declaring defeat instead of building a plan and accomplishing it in segments within a reasonable period of time.

Like in the story of “Goldilocks and the Three Bears,” it needs to be not too action filled and not too unplanned. It needs to be just right. And the balance of action filled and planned will probably ebb and flow over time. This is sometimes known as balance and harmony.

BACK TO SACRIFICES AND TRADE-OFFS

I don’t want to move on without making some recommendations about sacrifices and trade-offs for your consideration.

Sometimes we will see them coming. Sometimes we won’t. They may be something we chose. They could also be something that is imposed on us. Whichever combination you face at any given moment, comparing them to your template of characteristics should help inform your sacrifice or trade-off choices.

It’s easy, and even natural, for us to focus on what’s going on in the moment—be it a problem of your own or a loved one’s, an opportunity, a sudden curve in the roadway of life, or getting what you’ve wanted and not quite knowing what to do with it—and deal with it as a one-off situation and move on. Even if we make great one-off decisions in the heat of the moment and take excellent one-off actions, they are unlikely to come together in a coherent way when we look back at them over our shoulder and wonder how we got to where we are. We each need the larger framework of intended life characteristics within which to make smart decisions/take actions that are congruent and really helpful in the long run.

When I am working with career clients, I frequently have to remind them that a series of jobs, even good jobs, do not make a career. They are just a series of employment situations. To make a career, you need a series of jobs that link together to build 1) an evolving combination of marketable experience and expertise, 2) an increasing opportunity for future promotion and/or income increase, 3) the network of relationships that are helpful now and will be even more helpful in the future, and 4) a way to stay even with or ahead of the curve for what employers and industries are going to need in the future. This kind of career management is not only applicable to jobs. This is also applicable to that cluster of work for pay we know variously as freelancing, project work, the gig economy, entrepreneurial activities, and self-employment. Great career management requires longer-term intentions, an incremental plan, and regular updating based on new information.

The same applies to our retirement and life planning. Current decisions and activities made with an eye to one’s thoughtful and periodically updated/overarching list of desired life characteristics are much more likely to have a positive, rolling effect on overall life satisfaction and success than those that happen on a strictly one-off, heat-of-the-moment basis.

You are going to be sailing through uncharted waters. Your compass won’t work because magnetic forces keep changing. If you have a North Star, a set of guiding characteristics for your future, you can know you are generally going in the right direction.

SACRIFICES TO CONSIDER MAKING

Roles in Which You Are Solidified Like Fruit in Jell-O

You can see out but you can’t move much. By the time we are 50 or older, many of us are almost inseparable from our roles and the doing that comes with them. It’s how we know who we are, what contributions we are making, what we like and don’t like, and what we are growing tired of. All of us have multiple roles. It’s how other people know us best—beyond our names and faces—and it’s frequently how they think of us whether they know it or not. Sometimes it’s healthier not to immediately replace a role that we are leaving or is leaving us, letting some time go by and some dust settle before deciding when and if to replace it.

Brian is a banker. He goes to the bank every morning and comes home every night. He has for years. He sells banking services as easily as he breathes. He actually has a bathrobe with the bank’s crest on it. His community activities—and the awards he has been given because of them—have all been oriented around the bank. His role as visible community banker has probably been even more important than the next two on his priority list, husband and father. In a year and a half, Brian is going to retire. How well will this role serve him after retirement AND is there anything he should be doing to prepare for change before he actually retires?

Totally and Permanently There/Completion

Most people love the sense of recognition and reward with having arrived at completion. We’re finally there. We ran the course and finished well. We NEVER, EVER have to worry about or do that again. Whoops. Hold it a minute. It’s great to celebrate milestones and achievements. We are naturally doers and achievers and problem solvers. It’s in our culture. We graduate from college or get married or choose a career path with an amazing (and frequently self-deceiving) sense of permanence. Where “there” and “completion” get us into trouble is if they come with the assumption that we’ll never have to face this again or something is totally behind us. We’re past it. Whew! Only this probably doesn’t occur as often as we would like.

Brenda had a terrible time finding the right boyfriend. In the end, she couldn’t get along with them. So she focused on her career without much regret except for the difficulty she had in getting along with some of her male colleagues. Later in life—in her 50s—a fellow proposed and she said yes. Her assumption was that, once married, she had arrived; she was there; she would never have to deal with it again. No one told her that marriage is a work in progress, not a permanent arrangement at which you have arrived. Brenda and her husband are seeing a marriage counselor. She didn’t understand how fluid and spontaneous marriage can be.

The Do Trap

A friend of 35 years just sent me a text message. She was “blubbering” at the top of a ladder from frustration. In her mid-60s she is one of the most independent, determined, and driven people I know. And that’s saying something. Her email concluded with the notion that no matter how hard she has tried otherwise, in her heart she still believes she is only as good as what she can get done today. She feels she has no permanent value. There she is at the top of the ladder high up in her garage only to discover she needed another set of hands and couldn’t do it by herself. Does she need to stop doing? Probably not. Will she be able to do less as she grows older? Probably. What needs to change? Her utter dependence upon her daily doing for her personal sense of value, place, and worth. There is nothing wrong with doing. The difficulty—the trap—is if you have no sense of yourself and instead have diminished worth if you aren’t doing.

Relationships That Don’t Serve Us Well Anymore

Ryan and Jennifer were friends with the couple who lived next door for years. They had boys and girls the same ages. The kids were inseparable. Almost everything was about the kids in those years: scouts, school, sports, dance lessons, piano recitals, giggling kids underfoot and always running in and out. They were extended family for each other and always there to back each other up. Only when the last of the kids graduated from high school did it occur to the parents how little they actually had in common as adults. For a long time, they tried going out to dinner periodically but always ended up talking about where the kids were and what they were up to. The neighbors continued to love those conversations. Ryan and Jennifer eventually became bored to death. They were still parents, of course, but through the passing years they had each developed other interests, friends, and possibilities. The dinners, painfully, grew further and further apart until they stopped entirely.

Objects, Including Our History and Others’ History

“Are you finally ready to get rid of your childhood tennis racket and that swimming trophy from your fifth-grade swim team?” Alice asked her husband, Phil. “We’ve dragged that stuff through four houses now.”

“That set of glasses belongs to my parents. They were wedding presents,” Phil exclaimed. “And how about those tablecloths taking up so much room in the drawer? They belonged to your mother but you never want to use them because they are so much work to wash and then perfectly iron.” Alice put her hands on her hips. “Unfortunately, I’m getting less and less romantic about your parents’ glasses and my parents’ tablecloths. When we were first married, they were historic treasures, proof of our being grown-ups ourselves, and a connection to our own family stories. All four of our parents have been gone a long time now. I’m for getting rid of all of them, but let’s sit down first and ask the smartest questions we can. One, what of all this stuff is really important to us other than the last connections to our parents? Two, what benefit is any of this stuff to us now and in the future? Three, is there anything here any of the kids would like and we won’t feel like we’re dumping stuff on them? If we can agree there is no benefit and we can each keep two objects that connect us to our parents, let’s agree we’re putting our After 50 skills to good use and move ahead.”

Excessively Secure, Familiar, and Comfortable

“What’s the point of planning if this author keeps saying we can only have a five-year horizon? Sounds like a lot of work to me to create a plan, update it constantly, adapt the plan and ourselves to the emerging realities, and then do it all over again. I know change is happening. Nevertheless, I don’t see it affecting us very much. I just want a 15-year plan that will come true. I want us to create it, type it into the computer, print it out to prove we did it, put in a file, and revisit every five years to celebrate how on track we continue to be. Otherwise it’s just work and who needs that?” It’s easy to trick ourselves into thinking that a plan is the same as a guarantee. It’s also easy for many of us to assume that if things don’t go according to plan we’re somehow being punished like children. The fact is, plans are an important set of intentions. They aren’t guarantees.

A Sense of Having Decided on Our Irrefutable Favorites

“I like my meat and potatoes. They are a metaphor for me of comfort, familiarity, and stability. When I was a kid, China might as well have been on another planet. Italy was where other kids’ grandparents or great grandparents came from. Syria, who had ever heard of Syria? And Africa was a far-off land populated by wild beasts and head hunters. I like my meat and potatoes. Why do you need to keep exposing me to other cuisines and strange flavors? I’m standing here saying I like my meat and potatoes and you want me to go out for Ethiopian food tonight? Have you no mercy or shame?” No doubt, we are entitled to having our favorites. However, it’s dangerously easy to settle into having the same favorites at 58 that we had at 18. They are comfortable, familiar, and untroubling. It’s also dangerously tempting to blame others—using shame—to avoid trying new things. When is your favorite really a favorite? When is your favorite actually the product of untested and unchallenged repetition? Only you can know.

Goal Addiction

“We all benefit from having goals, dear. But as we get older, if we’re only as good as our most recent accomplishment, we have failed to get off the merry-go-round of our 30s and 40s. What can I say of the 70-year-old who sincerely believes he is only as good as his golf score this morning or his last card game winnings? What can I say of a man, my husband, who absolutely cannot rest until he has killed both an alligator and a lion with a bow and arrow? I’m happy you have goals. They should, however, be an integrated part of supporting what we want our life to be for the next 10 years. I feel like you leave the ‘what we want our life to be like’ part up to me while you move your ego from proof to proof and goal to goal, utterly unrelated to your participation in the quality of our life together. I’m getting really tired of it.”

For many of us, goals have been a way of life. Losing weight. Making money. Taking better care of ourselves and our loved ones. Visiting every continent. Owning a house. Getting an MBA or an MA. Getting the kids into a great college. They gave us energy. Saving enough money—a nickel or dime or quarter at a time—to buy a new bicycle. Goals gave us excitement and purpose. They validated and caressed us with the pleasure of achievement. We moved from goal to goal. Do we continue to need goals After 50? Absolutely, yes. Then what’s so different about the role of goals After—and well After—50?

MY STORY

When I was a little boy, cake was all about the frosting. The baked part existed as a foundation for the greater, more important, exterior sweetness. My father always wanted a cherry or rhubarb pie for his birthdays. I thought he was absolutely nuts. Neither of us understood the cake metaphor at the time.

Through the years, I have come to appreciate the fullness of the cake and frosting together. I no longer eat the cake part first to get it out of the way for the real main event: the frosting.

Cake and frosting are a metaphor to me now. I still want the frosting and get pleasure from it. Yet, over time, the focus and combination has subtly shifted. I am more like the cake, substantial and freestanding and solid. The goal achievement is now more like the frosting: important, stimulating, colorful, and sweet. I still get a lot from it and often want more, but—like the cake—I’m solid and OK regardless of the frosting. Frosting decorates the core or cake. It isn’t the core.

This is what I would wish for all of us as we plan and live our retirement and our lives: lots of sweetness and the right kinds of goal/achievement stimulation for a high-quality retirement and life. But we no longer have to be dependent upon it—either its size or recentness—for us to be deeply OK. Instead we are our own favorite, well-blended, solid kind of cake that benefits from frosting but no longer needs it as evidence or proof or source of primary, temporary identity.

If you aren’t OK unless you have a recent goal achievement and at least one in process, then you might want to reconsider goals and whether or not you have a goal addiction. I totally believe in goals and achievement over 50, but not as the primary, and in some cases only, way to be OK.

TRADE-OFFS TO CONSIDER MAKING

A Smart Amount of Risk

“I understand your need to be careful, dear. We have money but not to burn. Here we are in our 50s. I’m focusing on what we want our life to be like while you are focusing on taking as few risks as possible to conserve and protect what we have. I think we have recuperative years now that we won’t have in our 70s if something goes wrong. We have time to plan. We have time to start small with little capital and low overhead. I really want to start this small, weekend business now as part of our retirement plan. Only living on savings might be a dumb idea 25 years from now. What would happen if we had a small, reliable income stream in addition AND equity in a small business that we could eventually sell. I’m asking you to take the right amount of smart risk with me now as an investment in our future.”

Short-Term Planning

Short-term planning is an ongoing, living, breathing process. It becomes long-term planning through updating and adapting iteratively over time. Well done, short-term planning is combined with the right amount of effort in a cycle that repeatedly includes research and conclusion. See the Learning and Decision Making Loop (Figure 3-1).

Replenished Networks of Colleagues and Friends and Skill/Expertise-Based Connections

In this highly connected, expanding world, it’s seldom possible for us to know all the people and have all of the necessary expertise. We’re going to live longer and work longer. We’re going to need more money to pay for those years. We’re going to have to have new and upgraded skills—not to mention vitality—to find our places in the radically altering world of work for pay, which may eventually look at least as much like freelancing as it has looked like permanent jobs in the past. This all means we need access to the people who are known by the people we know/are connected to. This means understanding and effectively using all the technological tools necessary for an expanded, effective professional footprint in the world of work for pay. This means—and we are finite beings—focusing for the most part on those professional relationships that can make the difference and open doors for us.

Empty Space Technique

I like using what I call the empty space. You can design your own. Mine looks like a large room with hardwood floors and high, hardwood ceiling, glass walls with drapes that can be closed at night, comfortable ambient lighting, a gas stove that looks like a kiva, and a front door. That’s it. No rugs or furniture. When I remove something from my life—an object or a role or a skill or something that gave me comfort and I depended upon in the past but no longer will serve me well—my trade-off is that I can, however briefly, grieve its passing by spending some time in my quiet, empty space. My discipline is that I cannot rush out and find anything at all to fill the recently emptied space. First, I have to make friends, yet again, with the empty space and settle into its comfort. Then I go through the Learning and Decision Making Loop (see Chapter 3) to observe and choose what I want, if anything, to take up the space recently occupied and now not. Usually I end up comfortable with the empty space and without desire to put anything in it. Sometimes I simply announce silently to the world that I have some empty space and am awaiting the unplanned arrival of the unplanned thing that will be perfect for the space. Occasionally, I remember that I’ve always wanted X (object, role, etc.) and previously didn’t have life space for it. So I go and check it out to see if I still really want it and if it will fit into the space available without massive rearranging of everything else.

A Different Kind of Deciding and Learning

Most of us came out of a learning culture, which assumed what we didn’t know. An expert (content and teaching) organized the information, we learned (memorized it through rote or physical repetition), and we aspired to get an A on the quiz or at least to pass it so we could move on to the next one. Most of us also saw learning as something to accomplish and move beyond to the next item on our calendar or agenda. In fact, it doesn’t work that way when creating intentions, having a plan, updating the plan periodically, and updating ourselves and our perspectives as well. It doesn’t end and we can’t move beyond it. We can ignore it, but that works against us in the short and long term.

A different starting point for learning is going to be frequently required of us between 50 and elderly. We may or may not like it but it will be required anyway. The new starting point won’t be acknowledging what we don’t know and pursuing the necessary learning. It will be a variation of “I Don’t Know What I Don’t Know.” It’s called pioneering for a reason. There will be no one with greater expertise regarding your life than you have. There will be experts with recommendations, but the choices to be made will all be yours. Imagine you step, like a pilgrim, off a ship onto a beach with a big rock. You don’t know the territory. You don’t know the culture. You don’t know the topography. You don’t know the rules. What you already know could be wonderful or useless. You don’t know how much of either one. Welcome to I Don’t Know What I Don’t Know. It’s the starting place for all pioneers. The new learning process will look like our Chapter 3 Learning and Decision Making Loop viewed from its side, like a bedspring or an ascending coil. Every rotation takes us from I Don’t Know What I Don’t Know to I Know What I Don’t Know, to finding the necessary resources and experience so we can learn it, to knowing it and then coming face-to-face, as learning loops will tend to do, with the next instance of I Don’t Know What I Don’t Know. This will apply in work for pay, health, updating social networks, financial decision making, and lots of other life arenas.

By the time we are 50 years old, we will have to renew our conscious effort to replenish our educations and marketable skill sets, our key relationships, and our attitude toward change and the world. It won’t be just a matter of taking some classes and memorizing the material. We may well have to think and socialize in ways that are brand new to us. Here, moving rapidly into action—to reduce our anxiety or check an action off the list or spare us from facing what’s really going on—will work against us. Certainly we’ll need action but only in balance with the other stops on the learning loop.

Once again, this requires paying attention and working with what is, rather than working with what we wish. A rich and rewarding life requires conscious health of all kinds, including learning and adaptability health. I realize we have covered much more material than sacrifices and trade-offs. In addition to looking at them, we have seized the opportunity to build the bigger life context—what you are choosing to characterize your future—and built a tool that can and should be updated and revisited regularly.

And we’ve pulled a number of pieces together so that your three-perspective retirement or life plan is beginning to emerge.

Now on to Handling the Surprises and the Curves.