Chapter 8

MAKING IT REAL

NEED A LITTLE BREATHER AFTER ALL THE WORK WE’VE DONE? Well, sit back, relax, and let me tell you a few stories.

Up to now, we’ve been working in the realm of the hypothetical, and the picture can get pretty fuzzy without some tangible examples to solidify our understanding of the process and results. If you can’t visualize the way your solution will play out in the everyday work of your organization, then you’re going to be dead in the water. To help you convert that theory into everyday action, let’s take a look at how all this information I’ve thrown at you has played out for a few different organizations. These how-they-did-it stories involve composites of real companies that PeopleFirm has worked with in the past few years and should give you a feel for how performance management can be successfully rebooted, while also providing some helpful tips that you might be able to apply as you create your own story.

I’ll begin by introducing you to a company I’m going to call Peace.org.

Story #1: Peace.org

THE STARTING PLACE. Peace.org is a nonprofit. Like many nonprofits, they are big on purpose but perpetually short on funds. Because the majority of their employees come to them feeling a connection to the mission of the organization, turnover has historically been low despite the low pay and long hours. However, in recent months they’ve lost a few of their key people to peer organizations. Another big change has occurred over the summer as well: the longstanding managing director has retired and has been replaced by a new leader.

THE DESTINATION. The new managing director was tasked by the board to double the impact that the organization is having across the globe. To meet this audacious goal, the organization is going to have to perform at a higher level than ever before, especially since doubling the impact does not mean doubling the resources. In the past, Peace.org had tried to force a corporate model of performance management onto the organization, based on the recommendation of a vocal board member. It failed miserably within their culture, and a set of the review templates literally became a dartboard in the break room. Understanding this history (since it was quite willingly shared by many of the team, and hey, the dartboard was evidence sitting right there in the break room), the new managing director decided that he needed to look for a new approach to increase performance and improve the retention of their key talent. He also recognized that funding would continue to be tight, so pay increases were not a viable option in the near future.

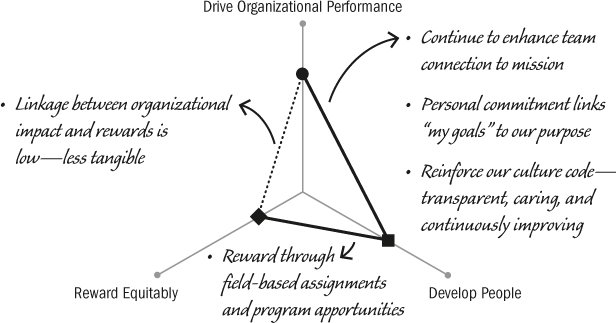

PEACE.ORG’S DESIGN PRINCIPLES AND FRAME. After working through the design process, the design team at Peace.org created their five design principles and determined that their frame should look something like the one in figure 8.1. Not surprisingly, their frame shows that they are high in drive organizational performance and develop people—the two key goals that the managing director wanted most to support.

The Peace.org team decided on the following design principles:

The new performance management solution will …

1. Increase every employee’s connection to our mission

2. Engage the full team in setting operational goals

3. Reinforce our culture code

4. Create mastery in all areas of our organization

5. Be simple and effective without getting in the way

Figure 8.1. Peace.org’s frame.

PEACE.ORG’S CONFIGURATION. As the team dug into configuring their solution, they made the choices shown in figure 8.2:

Figure 8.2. Configuration example: Peace.org.

MY FAVORITE PM PRACTICE. The PM Practice that has been the biggest hit with the Peace.org team is the commitment process. Employees like it because they get the time and opportunity to explain their personal connection to the mission and how they want to grow with the organization, and leaders like it because they get to know more about how employees see themselves as part of the team (see figure 8.3). Each month during the all-hands meeting, two or three of the team members share their commitment with the group and talk about how things are going, what more they hope to do, and what they need from others to achieve their own aspirations. Over the past few years, the nature of the commitments has gotten more creative and taken on greater meaning within the organization.

Figure 8.3. Peace.org commitment postcard.

The Nature of Nonprofits

Research shows that nonprofit organizations often struggle when trying to apply for-profit performance models to their own, very different, organizations.1 Let’s take a look at why this misses the mark.

Defining performance

Organizational performance in the nonprofit sector is often hard to define. For-profit organizations can use a clear bottom line as both their reason for existence and their performance measurement. In contrast, nonprofit organizations are often built around varied and complex missions, making it difficult to define an obvious measurement of success. Since mission achievement is not typically tied directly to the organization’s ability to generate income, natural performance measures are rarely in place.

Cultural resistance

While nonprofit organizations are increasingly recognizing the need to bring more “business” practices into the management approach, many nonprofits resist these changes on a cultural level. And there’s nothing that is more “corporate” than a traditional performance program. Interesting research from the University of Georgia notes that “there is a high degree of idealism within the nonprofit sector and reluctance among nonprofit employees to acknowledge that they are involved in competitive, market-based activities, and, for ideological reasons, they are reluctant to use market analysis.”2

Having worked with a lot of nonprofit organizations, I’ve often experienced these struggles firsthand. But here’s the thing: the focus on measurement is less critical if we can unite those groups of passionate people to work collaboratively toward a compelling and shared goal. In fact, the idealism prevalent in nonprofits can be a huge strength (or a significant weakness, depending on how well it’s captured and leveraged). The strength of the idealism is realized when your performance design effectively taps into each individual’s connection to the mission. But that idealism can become debilitating if you introduce performance approaches that are perceived as being a distraction from productive work or contrary to the mission.

With these ideas in mind, here are a few tips for designing performance solutions for the nonprofit environment:

• Keep it simple: research has shown that the success of a system of nonprofit measures is directly proportional to its simplicity.3

• Heavily emphasize the role of the mission in your solution design.

• Clearly define strategies or actions that will help your team bridge the gap between the lofty mission and your near-term goals and needs.

• When looking for metrics, consider impact, the level of activity, and outcomes related to your program mission and purpose.

• Be creative with reward strategies. Understand what motivates the people in your organization. (Tip: it’s unlikely that pay is their top driver.)

• Don’t try to force models that are contrary to the culture or mission.

Story #2: Services.com

THE STARTING PLACE. Services.com is a global consulting firm and a great example for other professional services organizations, like consulting, engineering, legal, or accounting. The rhythm of their business is based on project cycles, and their main asset, their differentiator, is their people. Because it is all about their people, development and retention are very important. Services.com has multiple offices scattered across North America, many of which were added over the years by acquiring other smaller firms. Recently they’ve also expanded into Europe, with new offices in the UK, France, and Germany.

THE DESTINATION. The global head of people (GHP) recently participated in the development of the five-year strategy for the firm. The vision is to meet the needs of global clients while continuing to grow services revenue and expand the firm’s location footprint. Accomplishing this vision will require Services.com to create a more cohesive culture, increase the collaboration among their far-flung offices, and bring consistency to their methodologies, tools, and services within all key areas of practice. The GHP has outlined a set of talent initiatives to support this strategy. First out of that gate is reimaging their performance approach, since the company’s long history of acquisitions has rendered the current one uneven.

SERVICES.COM’S DESIGN PRINCIPLES AND FRAME. The GHP has built a design team that gives her a diversity of experience, culture, and background by blending resources from multiple offices, representatives from each legacy firm acquired, and people from each of their practice areas, as well as a few representatives from headquarters. Here’s how the team defined their design principles and PM frame, which you’ll notice is relatively balanced across all three design goals (see figure 8.4).

The Services.com team decided on the following design principles:

The new performance management solution will …

1. Align our global team to our vision and goals

2. Encourage collaboration and knowledge sharing organization-wide

3. Provide insight into global talent pools by areas of practice

4. Align base pay to capabilities, rewards for client growth and impact

5. Build global account capabilities and leaders

6. Fuel innovation and service advancement

7. Increase focus on client delivery satisfaction

Figure 8.4. Services.com’s frame.

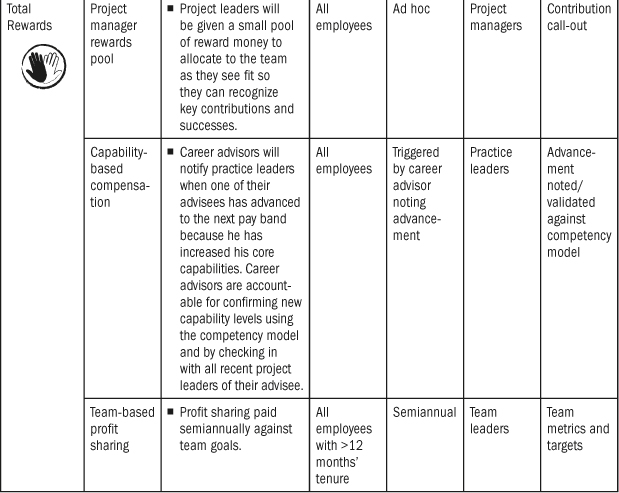

SERVICES.COM’S CONFIGURATION. And the direction in which they took their solution is shown in figure 8.5.

Figure 8.5. Configuration example: Services.com.

MY FAVORITE PM PRACTICE. The employees at Services.com loved moving away from the annual review to a project-based shared agreement. Why? Because the project agreement has a much tighter relationship to their work and their day-to-day focus. It also helps keep the dialogue open between the project leaders and team members (see figure 8.6).

Figure 8.6. Services.com shared agreement.

Considering the Global Organization

Managing performance at a global level warrants some serious additional thought. You must have a solid understanding of the legislative and regulatory issues, demographic trends, and labor laws from every jurisdiction in which you’ve got people. But all that said, I believe the most critical global consideration is to understand the cultural differences in your workforce. As Peter Drucker points out, “What managers do worldwide is about the same, but how they do it is different from culture to culture”4 (italics mine).

If we were to take a peek at what organizations have historically done to recognize these differences, we’d see that the tactics range dramatically from barely a nod (bad) to localized approaches custom designed for each unique culture (good). Sadly, barely a nod tends to prevail. Many global organizations continue to struggle to optimize their talent management processes in the ever-expanding global market.

So what is the right approach for implementing a global workforce? Well, I’ll say it again: there is no one-size-fits-all global solution. But if you agree with me that culture is the most important factor, then you’ll be sure to put a respectable amount of effort into understanding those cultural differences and how they will weigh into your solution design. In other words, they are quite likely to influence your overall philosophy (and thus your design principles), so they’ll require you to get aligned on how you plan to manage various global employee groups differently.

If you want to gain an appreciation for what will and won’t work here, I recommend turning to the extensive research conducted by Geert Hofstede on cultures in the workforce.5 In his research, Hofstede found five fundamental value dimensions that can be used to explain cultural diversity in the world. His “five-dimensional model” is one of the only models out there that’s based on rigorous cultural research, rather than opinion—which is why I like it. The five dimensions are as follows:

1. Power distance (PDI): The degree to which people accept that power is distributed unevenly within a group or society.

2. Individualism (IDV): The degree to which taking responsibility for oneself is more valued than belonging to a group that will look after its people in exchange for loyalty.

3. Masculinity (MAS): The degree to which people value performance and the status that derives from it, rather than quality of life and caring for others.

4. Uncertainty avoidance (UAI): The degree to which people develop mechanisms to avoid uncertainty.

5. Long-term orientation (LTO): The degree to which people value long-term goals and have a pragmatic approach, rather than being normative and short-term oriented.

What does all this mean for designing performance systems? Well, to clarify, let’s take a look at the traditional review process. The annual review is a widely accepted practice in countries like the United States and the UK. In the United States (and other countries with similar cultures), we score low on power distance and high on individualism. With those defining cultural factors, we find it easy to accept the idea that direct feedback is “the right way” to improve performance. This notion falls flat in high-power-distance countries, such as Japan and China. In fact, direct feedback in these cultures is likely to be seen as dishonorable and disrespectful. This means that we have to take a different approach that fits these cultural norms and expectations.

Another interesting dimension to consider is how your planning horizon may vary from culture to culture. When I was at Hitachi Consulting, I learned to appreciate the very real impact of working within an organization heavily influenced by Japanese leadership. One of the most notable differences was the manner in which the Japanese leaders thought about the short view and the long view. In the United States, we had a much shorter planning horizon, in contrast to our Japanese peers. This difference in focus radically influenced how each group defined what “good” looked like in both the short and long terms, as the very definition of those time frames varied radically from location to location. At times this created conflict and stress when setting targets and measuring success.

Rewarding equitably can be another tricky area as you navigate from culture to culture. The cash-is-king individual performance bonuses that we default to in countries such as the United States and the UK are not a good fit in cultures that focus on greater responsibility, larger spans of control, and wider territories as preferred rewards. Again, this showed up in my experience at Hitachi; the Japanese executives were quite surprised by our vice president’s bonus model, while the US leaders were struck by their Japanese counterparts’ lavish spending allowances. As they say, different strokes for different folks (or, in this case, different cultures, different expectations). In some cultures, cash rewards may even be perceived as petty. The headline? Tread carefully in this arena. If you’re planning a bonus program, be sure to consider which cultures value and expect bonuses, how you should measure them if you use them, and whether team or individual incentives would work best.

Beginning to feel a bit overwhelmed? Let me reinforce a few ideas that may help keep you grounded. First, when building your design team, remember to include individuals who can help you understand these cultural differences. They can be a voice for what will work and what is likely to fall flat. Get comfortable with allowing for differences across cultures. Your goal will be to find the best balance between meeting your desire for consistency and creating great experiences for your global team. Also, before you roll out your solution, test it in different geographies and cultures—not just the solution itself, but also the supporting content, since some degree of localization is likely to be needed on that as well. In the end, keep humanity at the forefront of your design, and never forget that this is about your people, not the process!

Story #3: Tech.com

THE STARTING PLACE. Tech.com is a fast-moving, forward-thinking technology company. They hire mostly systems engineers who are young and highly skilled—in other words, hard to get in the door and even harder to keep. Tech.com is a young company in their space, but they have proved that they have the chops to leapfrog the bigger players, since they’ve got innovative products and better speed to market. As you might expect from an organization comprising mostly millennials and techies, they cringe at any whiff of bureaucracy.

THE DESTINATION. The Tech.com leaders are seeking a way to inspire and keep the best technical talent without bogging them down in forms, processes, and red tape. They also need to keep their teams forward-thinking and tuned in to what’s going on in their market and how the technology is advancing. The company is doubling in size every twelve to eighteen months, and at that pace, training and onboarding new employees is a massive challenge.

TECH.COM’S DESIGN PRINCIPLES AND FRAME. The CEO engaged a small group of her best development leads and solution architects to help create a performance solution for their unique environment and needs. Here’s what they came up with (see figure 8.7).

The Tech.com team decided on the following design principles:

The new performance management solution will …

1. Differentiate rewards to those who deliver great solutions, on time

2. Accelerate the growth of developer skills and capabilities

3. Eradicate any noise; what matters is what you deliver

4. Pay at market based on engineer maturity model

5. Insist on current market knowledge

Figure 8.7. Tech.com’s frame.

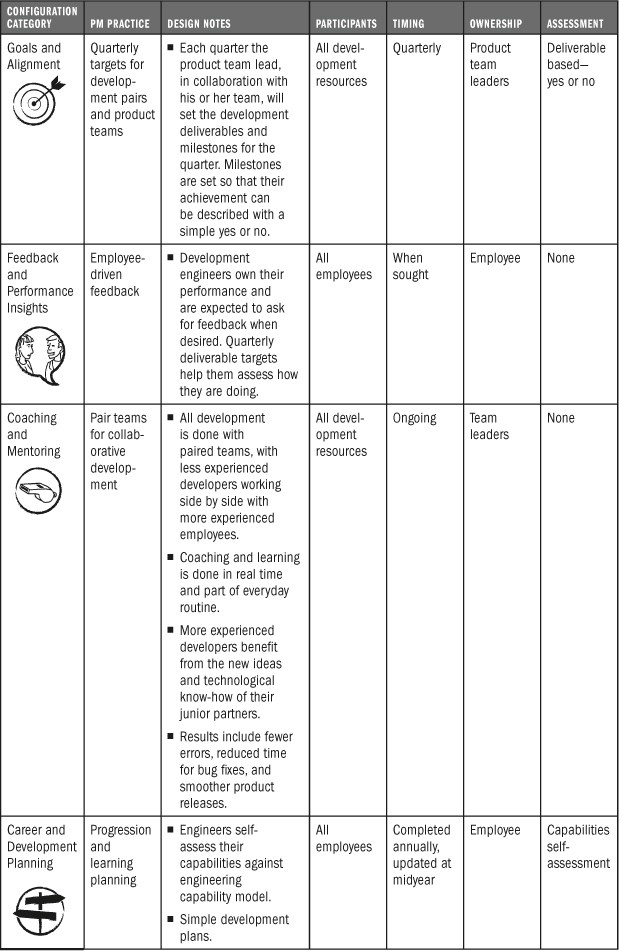

TECH.COM’S CONFIGURATION. With the goal of keeping it as simple as possible, they agreed to pilot the approach shown in figure 8.8.

Figure 8.8. Configuration example: Tech.com

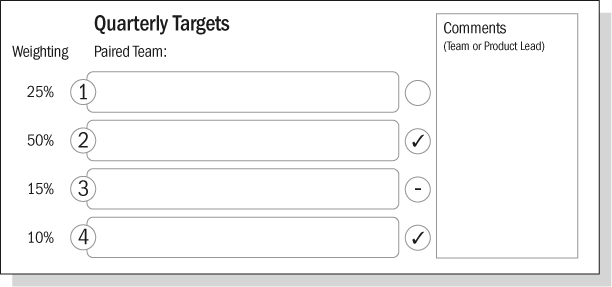

MY FAVORITE PM PRACTICE. The product team leads developed a simple form that they use to support the quarterly goals process for the paired development teams. In accordance with the product development plans, paired development teams work with their product leader to agree on key development targets and deliverables. Typically, one to four goals are set and then weighted by priority, workload, or importance. At the end of the quarter, these targets (and the assigned weighting) directly correlate with how much the team receives as their quarterly bonus (see figure 8.9).

Figure 8.9. Tech.com quarterly targets.

Competing for That Tricky STEM Talent

It seems like nearly every company I’ve worked with is struggling to attract and retain strong technical resources, whether or not it competes in the technology space. We can chalk up the demand to the advancement of science and technology’s role in nearly every industry, service, and product out there—combined with a shortage of the necessary STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) talent to support those needs. And while there’s a lot of literature available on how to meet the needs and expectations of this audience, it seems worth adding a few words on this tricky employee group, specifically in regard to performance strategies.

Let’s start with the employee’s point of view. While acknowledging that no two people will ever want or care about exactly the same things, we can still recognize some macro themes that come up again and again that resonate with STEM-oriented personalities. First, this group cares a great deal about their skills, knowledge, and experiences. They want to be current in their field, work with the latest and greatest in technology or science, and rub elbows with the best and brightest. Second, they like to be recognized for that mastery. This recognition can come in many forms, such as awards and certifications, patents, published works, or speaking at conferences—or simply being recognized by their peers as a “rock star” in their space. They also care deeply about having the freedom to invent, build, design, explore, and play in their field. After all, how can you ever be a master if you don’t have the time and space to practice your craft?

Now let’s look at what the organization needs from this group. Clearly those mastery skills are important to organizations too. Yet many companies struggle to give STEM talent the tools, training, and experiences needed to stay on the cutting edge of their field of practice. The more your performance solution can focus on identifying and aligning your best technical talent to the “coolest” work, the better.

Another common tension that organizations face is wanting all that STEM brainpower aimed at the right work, rather than being distracted by other things. To address this, we need to understand where the STEM skills live in our organization, which of those skills are critical to our business strategy, where the gaps are between what we have and what we need, and how we can optimize our resources to deliver against our highest needs. And while we definitely want to put more focus on directing that talent to the best work, we also need to balance that with this group’s desire for time and space to do their own thing. When you’re short on critical technical talent, it’s hard not to dedicate the talent that you do have 120 percent toward your priority agenda items as a company. However, you need to be a little more flexible in order to keep this very mobile group happy. Google and other forward-thinking companies have proved that letting your people use some percentage of their time on their own pet projects pays big dividends down the line.

So how should the desires and interests of both employee and employer influence your performance design? I recommend focusing on what both care about—in other words, the win-win. Here are some ideas on how to do that:

• Keep your approach simple. Why? This group tends to hate formality and bureaucracy, so do you really want to irritate them with the process? Also, this is a valuable resource, so optimizing their time is essential.

• Push as much authority and ownership as you can down the ranks. STEM folks don’t like hierarchy any more than they like bureaucracy. The flatter your structure, the better. Create more opportunities that allow them to work in networked teams with control over their own resources. This also means more employee-driven and peer-based approaches. Let them be the rock star in their crowd.

• Invest in building clear technical career paths, and in creating the content necessary to enabling and communicating those paths. Share information on how these employees can build their mastery within your organization, and provide them with resources outside the walls as well.

• Build a model where you can assess the technical skills, knowledge, and capabilities that are housed within your organization. A strong technical competency/capability model will do this. It will also help to have the technical career path agenda mentioned above.

• Ensure that your talent review processes prioritize mobility. In other words, keep your STEM talent moving to increase collaboration and the sharing of knowledge, and to enhance their growth, experiences, and learnings.

• Celebrate their brilliance (often). Find ways to highlight progress, solutions, invention, things of beauty, and innovation. This may be at a team level as much as it is at the individual level. Recognition can be as simple as a toast at the Friday happy hour or as formal and high visibility as company-wide recognition such as displaying patents or other awards prominently in the office halls, or granting innovation awards internally.

• Connect your investments and their rewards to the things these employees care about: building their mastery, recognition of that mastery, and the time and freedom to play.

Story #4: Retail.com

THE STARTING PLACE. Retail.com is a large national retailer with nearly a hundred stores in the United States and Canada. While they’ve been in existence for more than forty years, the past decade has seen exponential growth. Employees in the stores are hourly (with the exception of managers), and the employee mix tends to be a blend of long-tenured employees, employees who stick around for one to five years (often college students), and seasonal resources who come in at peak seasons. Beyond the sales teams, there are several other employee segments in the mix, including warehouse, a call center, an online team, and the groups at headquarters who manage marketing, merchandising, supply chain, HR, and other common back-office functions. Finally, it’s worth noting that the organization has a strong history of internal advancement. In fact, many people at headquarters, including several senior leaders, started on the retail floor.

THE DESTINATION. Retail.com’s fundamental belief is that happy customers equal continued business growth, and that happy customers are a result of great products and friendly, helpful service. Consequently, they have a key focus on continuing to increase the service levels that their employees provide their customers. They’ve also seen the fight for good talent heating up as the economy has improved. Not only do they want to be the employer of choice when competing in this hotter labor market, but also they hope to find more people who will stay longer with the team. They’ve found that having that solid and committed base of store employees is especially critical when entering new markets. Finally, they are interested in exploring how to build a performance management approach that works for their diverse employee groups. In recent years, it has become clear that what works for the headquarters team isn’t the best solution for store employees or the warehouse crews, and vice versa.

RETAIL.COM’S DESIGN PRINCIPLES AND FRAME. Retail.com put a lot of thought into their performance strategy, which they named “@ Our Best.” Early on in their design process, they made a couple of key decisions. First, they were going to design for four employee segments: sales associates in stores, headquarters employees and store managers, warehouse employees, and the call center and online teams. Second, they determined that they would create a core set of design principles that supported the entire organization, and then create one or two custom design principles that would apply only to each of the four unique employee segments. The following is what it looked like for the store sales associates.

The Retail.com team decided on the following design principles (see figure 8.10):

The new performance management solution will …

1. Enhance our culture of customer-centricity

2. Encourage internal movement and retention of talent

3. Build and reward great managers

4. Customize our approach to the unique needs of our employee segments while maintaining a consistent core

5. Empower store managers to drive team experience

6. Reward stores for strong performance at the team level

Figure 8.10 Retail.com’s frame.

RETAIL.COM’S CONFIGURATION. Retail.com aimed to keep @ Our Best simple for the store associates. Figure 8.11 shows their configuration.

Figure 8.11. Configuration example: Retail.com.

MY FAVORITE PM PRACTICE. Every six months, the store managers gather for a couple of days to share best practices, celebrate top-performing stores, learn about new programs, and talk about their teams. To support the preparation for the team conversation and to make the sharing of information easy, Retail.com built a simple employee profile form (see figure 8.11). Managers complete the form every six months for each of their team members. It’s extremely useful to have this information in a common format that allows sharing with other managers, and the very process of gathering the information and tuning in to each member of the store team has also proved to be of very high value. Quite simply, the nature of the exercise they call “stay interviews” reminds managers to ask those basic questions about the employees’ experiences, interests, desire for advancement, and level of satisfaction—questions that help people feel valued and listened to. Having engaged their people, managers can also easily identify those on their team who might be ready to move into management or take on more responsibility in the store or in other departments within Retail.com. And frankly, it never hurts to know who’s perfectly happy just staying in their sales roles.

Figure 8.12. Retail.com stay interview guide.

Don’t Overlook Hourly Workers

I’ve encountered a lot of people who think that these “modern” performance ideas don’t really relate to hourly or task-oriented roles. Be careful not to fall into that line of thinking. People are people, and whatever their role in an organization, they are all likely to “show up human.” They all want to be part of something, believe that what they do matters, and feel recognized for their contributions. Further, don’t make the mistake of assuming that all hourly employees are alike. They run the gamut from the shop-floor worker to the administrative assistant who welcomes you to the office each morning, and their needs and expectations might be very different. That said, there are commonalities that are worthy of thought if you have hourly and task-oriented roles in your organization.

First, you’ll often find that monetary rewards actually work well in this group, as employees in these roles are commonly paid less than their salaried coworkers. If this is the case, connect monetary rewards to near-term accomplishments. For example, monthly performance bonuses can be a great way to reward a manufacturing team, a construction crew, or groups that share similar attributes. Designing more near-term rewards will require you to get clear on measurement and create mechanisms for sharing those metrics with the team (e.g., performance or metrics boards posted in work environments).

Did you note the word team in that last sentence? Task-oriented departments are often managed best at the team level rather than individually. When designing your solution, find ways to push more responsibility and ownership of performance to the team as a whole. This may drive an uptick in performance, since self-managed teams have been known to create meaningful results.

It may complicate things if a union is involved, as this might limit your rewards options. In that case, turn your focus to driving organizational performance by creating greater connectivity to the value of the work, as well as the development of your people. In union environments, offering tools to help individuals build capabilities and skills can be a significant motivator, since mastering skills often aids employees in their advancement efforts.

Finally, whether you’re talking about the administrative assistant or the packaging team at the end of the manufacturing line, I recommend finding ways to connect your hourly employees to your customers. It’s a great motivator for them to hear directly from both internal and external customers about what is of value. It’s also a powerful mechanism for creating more meaning in their work. Think about it: is the performance of that administrative assistant likely to be measured by his internal customers (i.e., the people he supports) on how many words he types per minute or for the little details he manages and the extra effort he takes to personalize his approach? Make sure that they understand what matters to those customers and that they’re celebrated and rewarded for delivering on that promise. This works equally well in production environments, so don’t shy away from bringing the customer’s voice to those who directly influence the product or service they receive.

Write Your Own Story

I hope this chapter has helped to bring those theoretical ideas from the redesign process into clearer focus, and that the stories I’ve shared have inspired and energized you for the path ahead. However, I must add a word of warning before we move on to building and finally rebooting your program: as tempting as it may be to simply lift the design in one of these case studies and slap it onto your organization, resist that urge at all costs! Never forget that performance management solutions must vary from organization to organization so that they best support the various strategic needs, cultures, maturities, and business climates of each. Your solutions will, and should, look different from those of any other organization in the world—because there is no other company exactly like yours.